Table of Contents

ToggleCerebral vascular accidents (Stroke)

Stroke, medically termed a Cerebral Vascular Accident (CVA), represents an acute medical emergency characterized by rapid onset of neurological deficits resulting from a disturbance in the blood supply to the brain. This disruption leads to brain cell death due to a lack of oxygen and nutrients (ischemia) or direct damage from bleeding (hemorrhage). Often referred to as a "brain attack," stroke demands immediate medical attention as time is a critical factor in determining patient outcomes.

A stroke occurs when blood flow to an area of the brain is interrupted, either by blockage or rupture of a blood vessel. This interruption causes brain cells in the affected area to die. The brain is highly dependent on a continuous supply of oxygen and glucose, which are delivered by blood. Even a few minutes of interrupted blood flow can lead to irreversible damage and loss of brain function.

Significance as a Global Health Concern:

Stroke is a major global health challenge with profound implications for individuals, healthcare systems, and societies.

- Leading Cause of Adult Disability: Stroke is the primary cause of long-term disability in adults worldwide. Survivors often face a range of physical, cognitive, communication, and emotional challenges that can severely impact their quality of life and independence.

- Significant Mortality: Globally, stroke is the second leading cause of death. While mortality rates have declined in some high-income countries due to advances in acute treatment and prevention, it remains a critical cause of premature death, particularly in low- and middle-income countries.

- Economic Burden: The economic impact of stroke is immense, encompassing direct medical costs (hospitalization, medications, rehabilitation) and indirect costs (lost productivity, caregiver burden).

- Prevalence: Millions of people worldwide suffer a stroke each year, and the global burden is projected to increase due to aging populations and the rising prevalence of risk factors.

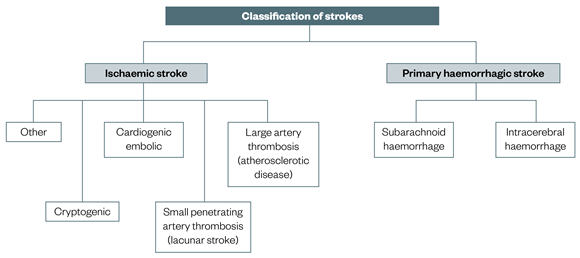

Main Types of Stroke:

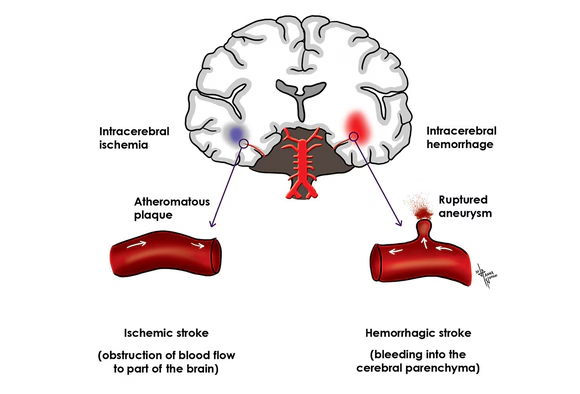

Strokes are broadly categorized into two main types, distinguished by the mechanism of blood flow disruption:

A. Ischemic Stroke (Approximately 87% of all strokes):

- Thrombotic Stroke: A blood clot (thrombus) forms in an artery that supplies blood to the brain, often in arteries damaged by atherosclerosis (hardening and narrowing of arteries due to plaque buildup).

- Embolic Stroke: A blood clot or other debris forms elsewhere in the body (commonly the heart) and travels through the bloodstream to the brain, where it lodges in a narrower artery and blocks blood flow.

- Lacunar Stroke: Occurs when blood flow is blocked to a small artery that supplies deep brain structures. These are often associated with chronic hypertension and diabetes, affecting very small blood vessels.

B. Hemorrhagic Stroke (Approximately 13% of all strokes):

- Intracerebral Hemorrhage (ICH): Bleeding directly into the brain tissue, often caused by uncontrolled high blood pressure (hypertension) or structural abnormalities like arteriovenous malformations (AVMs).

- Subarachnoid Hemorrhage (SAH): Bleeding occurs in the subarachnoid space, the area between the brain and the thin tissues that cover the brain. This is most commonly caused by a ruptured cerebral aneurysm (a balloon-like bulge in an artery).

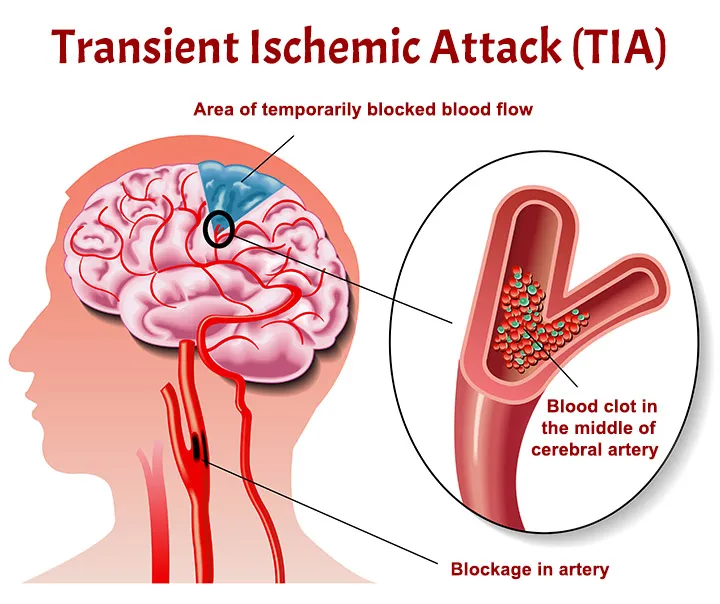

Transient Ischemic Attack (TIA) - A "Mini-Stroke" and Warning Sign:

- A TIA is often referred to as a "mini-stroke" because it involves a temporary blockage of blood flow to the brain, causing stroke-like symptoms that typically last for a few minutes to less than 24 hours, with no permanent brain damage.

- Crucial Significance: TIAs are critical warning signs that a person is at high risk for a full-blown stroke. They should be treated as a medical emergency, prompting immediate evaluation to identify the cause and initiate preventive measures. Ignoring a TIA significantly increases the likelihood of a future, more debilitating stroke.

Etiology & Risk Factors of Cerebral Vascular Accidents (Stroke)

The occurrence of a stroke is rarely an isolated event; it is usually the culmination of various underlying conditions and lifestyle choices that damage blood vessels and impair their function. Identifying and managing these factors is paramount in reducing stroke incidence and recurrence.

Stroke risk factors can be broadly categorized into modifiable (those that can be changed or treated) and non-modifiable (those that cannot be changed).

1. Ischemic Stroke Causes:

Ischemic strokes arise from conditions that lead to the formation of blood clots or blockages in cerebral arteries.

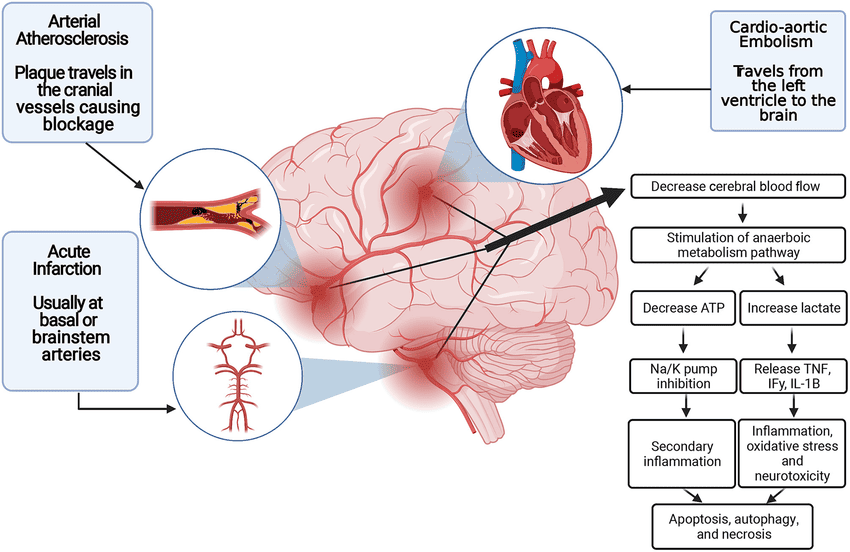

A. Atherosclerosis: The most common underlying cause.

- Large Vessel Atherosclerosis: Plaque buildup in the larger arteries (e.g., carotid arteries in the neck, vertebral arteries, and their major intracranial branches) can lead to:

- Thrombotic Stroke: A clot forms directly on the atherosclerotic plaque, completely blocking blood flow.

- Artery-to-Artery Embolism: Fragments of plaque or clot from an atherosclerotic artery break off and travel downstream to block a smaller brain artery.

- Small Vessel Disease (Lacunar Infarcts): Atherosclerosis affects the small, penetrating arteries deep within the brain, often due to long-standing hypertension and diabetes, leading to small, deep infarcts.

B. Cardioembolism: Blood clots form in the heart and travel to the brain.

- Atrial Fibrillation (AFib): The most common cardiac source of emboli. Irregular and rapid heart rhythm leads to blood pooling in the atria, forming clots that can then dislodge and travel to the brain.

- Valvular Heart Disease: Rheumatic heart disease, prosthetic heart valves, or endocarditis can promote clot formation.

- Myocardial Infarction (MI): Especially large anterior MIs, can lead to mural thrombi formation in the heart ventricles.

- Patent Foramen Ovale (PFO): A small opening between the atria that fails to close after birth. While often benign, it can allow clots from the venous system (e.g., DVT) to bypass the lungs and enter the arterial circulation (paradoxical embolism).

- Congestive Heart Failure: Reduced cardiac output can contribute to stasis and clot formation.

C. Hypercoagulable States: Conditions that increase the blood's tendency to clot.

- Inherited: Factor V Leiden mutation, protein C or S deficiency, antithrombin III deficiency, antiphospholipid syndrome.

- Acquired: Cancer, pregnancy/puerperium, oral contraceptive use, myeloproliferative disorders.

D. Vasculitis: .

Inflammation of blood vessels, which can lead to narrowing, occlusion, or rupture

- Primary CNS Vasculitis: Affects only the brain's blood vessels.

- Systemic Vasculitis: Conditions like giant cell arteritis, polyarteritis nodosa, or lupus can involve cerebral vessels.

E. Arterial Dissection:

A tear in the inner lining of an artery (e.g., carotid or vertebral artery), allowing blood to accumulate within the vessel wall. This can lead to narrowing, occlusion, or can be a source of emboli. Often associated with trauma (even minor) or connective tissue disorders.

F. Other Less Common Causes:

Migraine with aura, fibromuscular dysplasia, Moyamoya disease, illicit drug use (e.g., cocaine, amphetamines).

Hemorrhagic Stroke Causes:

Hemorrhagic strokes result from bleeding into the brain tissue or surrounding spaces.

A. Hypertension (Chronic Uncontrolled):

- The single most common cause of intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH), accounting for a significant majority. Chronic high blood pressure damages small blood vessels deep within the brain, making them prone to rupture.

- Common locations: basal ganglia, thalamus, pons, cerebellum.

B. Cerebral Aneurysms:

- The primary cause of subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). An aneurysm is a weakened, balloon-like bulge in an artery wall. When it ruptures, blood spills into the subarachnoid space.

C. Arteriovenous Malformations (AVMs):

- Congenital tangles of abnormal, fragile blood vessels that directly shunt blood from arteries to veins, bypassing the capillary system. They lack the normal support structure of capillaries and are prone to rupture, causing either ICH or SAH.

D. Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy (CAA):

- Accumulation of amyloid protein in the walls of small and medium-sized arteries in the brain's cortex and meninges. This weakens the vessels, making them prone to lobar ICH, especially in older adults and often recurrent.

E. Coagulopathies / Anticoagulant Therapy:

- Disorders that impair blood clotting (e.g., hemophilia, thrombocytopenia) or medications that thin the blood (e.g., warfarin, direct oral anticoagulants) significantly increase the risk of hemorrhage.

F. Illicit Drug Use:

- Cocaine and methamphetamine use are strongly associated with both ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes, often due to acute severe hypertension, vasospasm, or vasculitis.

G. Tumors:

- Brain tumors can sometimes bleed into themselves or surrounding tissue, particularly highly vascular tumors like glioblastomas or metastases.

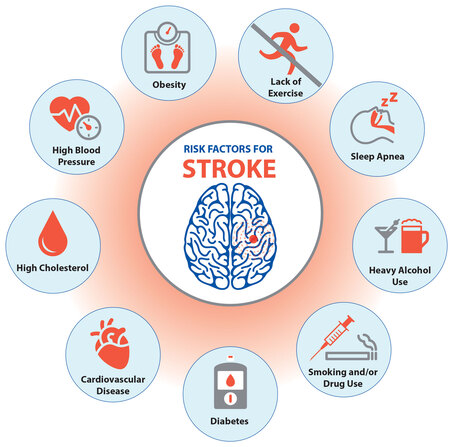

Risk Factors (Modifiable vs. Non-Modifiable):

Understanding these risk factors is crucial for both primary prevention (preventing a first stroke) and secondary prevention (preventing recurrence).

A. Modifiable Risk Factors (Can be controlled or treated):

- Hypertension (High Blood Pressure): The single most important modifiable risk factor for both ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke. Consistent control is vital.

- Diabetes Mellitus: Damages blood vessels throughout the body, increasing the risk of atherosclerosis and small vessel disease.

- Hyperlipidemia (High Cholesterol): Contributes to atherosclerosis.

- Atrial Fibrillation: As discussed, a major cardioembolic source.

- Smoking: Damages blood vessels, increases blood pressure, promotes clot formation, and reduces oxygen delivery. Both active smoking and secondhand smoke are harmful.

- Obesity: Linked to hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia.

- Physical Inactivity: Contributes to obesity, hypertension, and diabetes.

- Unhealthy Diet: High in saturated/trans fats, cholesterol, sodium, and refined sugars contributes to metabolic risk factors.

- Excessive Alcohol Intake: Increases blood pressure and can contribute to hemorrhagic stroke.

- Carotid Artery Disease: Significant narrowing (stenosis) of the carotid arteries due to atherosclerosis.

- Sleep Apnea: Linked to hypertension and AFib.

- Oral Contraceptive Use: Particularly in women who smoke or have other risk factors, can increase clot risk.

- Illicit Drug Use: As mentioned above.

B. Non-Modifiable Risk Factors (Cannot be changed):

- Age: The risk of stroke significantly increases with age, particularly after 55.

- Gender: Stroke incidence is slightly higher in men at younger ages, but women have higher lifetime risk due to longer lifespan and hormonal factors. Women also have worse outcomes.

- Race/Ethnicity: African Americans, Hispanic Americans, and some Asian populations have a higher incidence and mortality rate from stroke, often linked to higher prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, and sickle cell disease.

- Family History: A family history of stroke, especially at a younger age, indicates increased risk.

- Previous Stroke or TIA: The strongest predictor of a future stroke.

Pathophysiology of Cerebral Vascular Accidents (Stroke)

The pathophysiology of stroke describes the cascade of events that occur at the cellular and molecular levels following the disruption of cerebral blood flow. While the initiating events differ significantly between ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke, both ultimately lead to neuronal damage and death, albeit through distinct mechanisms.

Ischemic Stroke Pathophysiology:

Ischemic stroke occurs when blood flow to a region of the brain is insufficient to meet metabolic demands, leading to a complex series of detrimental biochemical and cellular events.

A. Cerebral Blood Flow (CBF) Interruption and Energy Failure:

- Core Infarct: When CBF falls below a critical threshold (typically <10-12 mL/100g/min), neurons cannot maintain their metabolic integrity. Oxygen and glucose delivery cease.

- ATP Depletion: The brain's high metabolic rate and reliance on aerobic respiration mean that within seconds of ischemia, ATP (adenosine triphosphate) stores are depleted.

- Ion Pump Failure: ATP-dependent ion pumps (e.g., Na+/K+-ATPase) fail, leading to depolarization of neuronal membranes.

- Cellular Edema: Sodium and water rush into the cells, causing cytotoxic edema, which swells the cells and compromises their function.

B. Excitotoxicity (Glutamate Release):

- Depolarization triggers the massive release of excitatory neurotransmitters, particularly glutamate, into the synaptic cleft.

- Glutamate binds to its receptors (e.g., NMDA, AMPA) on postsynaptic neurons, leading to excessive influx of calcium (Ca2+) into the cells.

- Intracellular Calcium Overload: High levels of intracellular Ca2+ activate numerous destructive enzymes (proteases, lipases, endonucleases), which break down proteins, lipids (damaging cell membranes), and DNA, leading to cell death. It also impairs mitochondrial function.

C. Oxidative Stress and Free Radical Formation:

- Mitochondrial dysfunction and the subsequent reintroduction of oxygen during reperfusion (if it occurs) generate an excessive amount of reactive oxygen species (ROS), also known as free radicals.

- ROS cause further damage to cellular components, including lipids (lipid peroxidation of cell membranes), proteins, and DNA, exacerbating neuronal injury.

D. Inflammation and Immune Response:

- Within hours of ischemia, an inflammatory cascade is initiated. Microglia (resident immune cells of the brain) become activated, and peripheral immune cells (neutrophils, macrophages, lymphocytes) are recruited to the ischemic site.

- These cells release pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs).

- Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB) Disruption: MMPs degrade the extracellular matrix and tight junctions, leading to BBB breakdown. This allows further influx of immune cells and plasma proteins, contributing to vasogenic edema (fluid accumulation outside cells in the interstitial space) and potentially hemorrhagic transformation.

E. Apoptosis and Necrosis:

- Necrosis: Rapid, uncontrolled cell death occurring in the ischemic core due to severe energy failure and membrane damage.

- Apoptosis: Programmed cell death, a slower, more regulated process that is triggered in the surrounding areas of less severe ischemia (penumbra). This is a target for neuroprotective therapies.

F. The Ischemic Penumbra:

- A critical concept in ischemic stroke. The penumbra is a region of brain tissue surrounding the severely ischemic core. In this area, blood flow is reduced (typically 20-50% of normal), but it is still sufficient to maintain cellular structure, though not function.

- Neurons in the penumbra are electrically silent but still viable. They are "at risk" but potentially salvageable if blood flow is restored quickly.

- The goal of acute stroke treatment (e.g., thrombolysis, thrombectomy) is to rapidly re-establish blood flow to the penumbra to prevent its progression to irreversible infarction, thereby minimizing neurological deficit.

Hemorrhagic Stroke Pathophysiology:

Hemorrhagic stroke involves bleeding directly into the brain tissue (ICH) or surrounding spaces (SAH), leading to brain injury through distinct mechanisms.

A. Direct Mechanical Tissue Compression and Destruction:

- Hematoma Formation: The extravasated blood forms a mass (hematoma) that physically compresses and displaces surrounding brain tissue.

- Direct Damage: Neurons in direct contact with the expanding hematoma are mechanically crushed and destroyed.

- Mass Effect: A large hematoma can cause a significant "mass effect," leading to shifts in brain structures (e.g., midline shift) and potentially herniation.

B. Increased Intracranial Pressure (ICP) and Reduced Cerebral Perfusion Pressure (CPP):

- Volume Expansion: The accumulating blood increases the overall volume within the rigid skull, leading to a rapid rise in ICP.

- Reduced CPP: Increased ICP directly reduces the cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP = Mean Arterial Pressure - ICP), compromising blood flow to unaffected areas of the brain and potentially causing secondary ischemia.

- Hydrocephalus: Blood in the subarachnoid space (SAH) or intraventricular hemorrhage can block cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) flow or absorption, leading to hydrocephalus and further ICP elevation.

C. Inflammatory Response to Extravasated Blood:

- Blood is highly irritating to brain tissue. The components of blood (e.g., hemoglobin, iron, thrombin) are toxic to neurons and glia.

- Inflammatory Cascade: An inflammatory response is triggered, involving microglia and astrocytes, leading to the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines.

- Edema: Inflammation contributes to perihematomal edema (swelling around the hematoma), which further exacerbates mass effect and ICP.

D. Excitotoxicity from Blood Products:

- Hemoglobin breakdown products (e.g., iron, heme) and thrombin (a coagulation factor present in the blood clot) can activate receptors (e.g., thrombin receptors) and generate free radicals, contributing to oxidative stress and excitotoxicity, similar to ischemic stroke.

E. Vasospasm (Primarily in SAH):

- After subarachnoid hemorrhage, blood breakdown products (e.g., oxyhemoglobin) in the subarachnoid space can trigger severe constriction of cerebral arteries, known as vasospasm.

- Delayed Cerebral Ischemia (DCI): Vasospasm typically develops several days after SAH and can lead to delayed cerebral ischemia and infarction, significantly worsening neurological outcomes.

Classifications & Types of Cerebral Vascular Accident

A thorough understanding of stroke classifications is essential for accurate diagnosis, appropriate treatment selection, and prognostication. Strokes are categorized based on their underlying cause, location, and the specific vascular territory affected.

1. Ischemic Stroke Subtypes (TOAST Classification):

The Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST) classification is widely used to categorize ischemic strokes based on their probable etiology. This helps guide secondary prevention strategies.

A. Large-Artery Atherosclerosis (LAA):

- Mechanism: Significant stenosis (narrowing) or occlusion of a major intracranial or extracranial artery (e.g., carotid artery, vertebral artery, middle cerebral artery) due to atherosclerosis.

- Pathology: Can cause stroke by local thrombosis or by artery-to-artery embolism from the plaque surface.

- Clinical Presentation: Often presents with significant neurological deficits corresponding to the affected large vessel territory.

B. Cardioembolism (CE):

- Mechanism: A blood clot originating from the heart or a major vessel proximal to the brain travels to and blocks a cerebral artery.

- Sources: Atrial fibrillation, valvular heart disease, ventricular thrombi after MI, patent foramen ovale (PFO), endocarditis.

- Clinical Presentation: Often involves multiple vascular territories or sudden onset of severe deficits. Emboli tend to lodge in medium to large arteries.

C. Small-Vessel Occlusion (Lacunar Stroke):

- Mechanism: Occlusion of a single small penetrating artery (e.g., lenticulostriate arteries, pontine branches) that supplies deep brain structures (basal ganglia, thalamus, internal capsule, brainstem).

- Pathology: Primarily caused by lipohyalinosis or microatheroma due to chronic hypertension and diabetes.

- Clinical Presentation: Typically causes one of five classic lacunar syndromes (pure motor hemiparesis, pure sensory stroke, ataxic hemiparesis, dysarthria-clumsy hand syndrome, sensorimotor stroke) with no cortical signs (e.g., aphasia, neglect, hemianopsia). Lesions are typically small (<1.5 cm) on imaging.

D. Stroke of Other Determined Etiology:

- Mechanism: Less common but identified causes.

- Examples: Arterial dissection (carotid, vertebral), vasculitis, hypercoagulable states, migraine with aura, fibromuscular dysplasia, Moyamoya disease, drug-induced stroke.

E. Stroke of Undetermined Etiology (Cryptogenic Stroke):

- Mechanism: Despite thorough investigation, no clear cause for the stroke can be identified.

- Subtypes:

- No clear cause identified: After extensive workup.

- Two or more potential causes: E.g., a patient with both AFib and significant carotid stenosis, making it difficult to definitively attribute the cause.

- Incomplete evaluation: Due to various reasons (e.g., patient refusal, financial constraints).

- ESUS (Embolic Stroke of Undetermined Source): A specific subtype of cryptogenic stroke where imaging suggests an embolic mechanism, but no definite cardiac or arterial source is found.

Hemorrhagic Stroke Subtypes:

A. Intracerebral Hemorrhage (ICH):

- Lobar Hemorrhage: Occurs in the cerebral lobes, typically more superficial. Often associated with cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) or AVMs.

- Deep Hemorrhage: Occurs in the basal ganglia, thalamus, brainstem, or cerebellum. Most commonly caused by chronic hypertension.

B. Subarachnoid Hemorrhage (SAH):

- Aneurysmal SAH (85%): Rupture of a saccular (berry) aneurysm, typically located at arterial bifurcations in the Circle of Willis. This is a neurosurgical emergency.

- Non-Aneurysmal SAH (15%): Can be caused by perimesencephalic non-aneurysmal hemorrhage (benign prognosis), AVMs, trauma, or coagulopathies.

Transient Ischemic Attack (TIA):

- Historically defined by symptoms resolving within 24 hours. Modern definition emphasizes the absence of permanent tissue damage on imaging (e.g., MRI diffusion-weighted imaging).

Stroke Syndromes (by Vascular Territory):

While not a formal classification of stroke type, understanding the typical clinical syndromes associated with occlusion of specific cerebral arteries is crucial for localization and diagnosis.

A. Anterior Cerebral Artery (ACA) Syndrome:

- Deficits: Contralateral hemiparesis (leg > arm), contralateral hemisensory loss (leg > arm), abulia (lack of will), dysphasia (if dominant hemisphere), urinary incontinence.

B. Middle Cerebral Artery (MCA) Syndrome:

- Most Common: Supplies a large area of the cerebral hemispheres, including motor and sensory cortices, speech centers.

- Deficits (Dominant Hemisphere - typically left): Contralateral hemiplegia/hemiparesis (face and arm > leg), contralateral hemisensory loss (face and arm > leg), global aphasia (if large lesion), Broca's aphasia (expressive), Wernicke's aphasia (receptive), gaze deviation towards the lesion.

- Deficits (Non-Dominant Hemisphere - typically right): Contralateral hemiplegia/hemiparesis (face and arm > leg), contralateral hemisensory loss (face and arm > leg), left hemispatial neglect, anosognosia (unawareness of deficits), constructional apraxia.

C. Posterior Cerebral Artery (PCA) Syndrome:

- Deficits: Contralateral homonymous hemianopsia (visual field loss), visual hallucinations, memory deficits, sensory loss. Large lesions can cause ipsilateral third nerve palsy with contralateral hemiparesis (Weber's syndrome).

D. Vertebrobasilar System Syndrome:

- Supplies: Brainstem, cerebellum, and posterior cerebral hemispheres.

- Deficits: Highly variable due to dense packing of vital structures. Can include vertigo, ataxia, nystagmus, diplopia, dysarthria, dysphagia, cranial nerve palsies, and often bilateral motor/sensory deficits (e.g., "locked-in syndrome" with basilar artery occlusion).

Clinical Presentation (Signs & Symptoms) of Cerebral Vascular Accidents (Stroke)

The clinical presentation of stroke is highly variable, depending on the type of stroke, its location, size, and the specific brain functions affected. Stroke symptoms typically appear suddenly and without warning. Rapid recognition is crucial for timely intervention, and tools like "FAST" are designed to facilitate this.

General Presentation and Rapid Recognition (FAST):

The acronym FAST is a widely used public health campaign to help people recognize the most common signs of a stroke and understand the urgency of calling emergency services.

- F - Face Drooping: Ask the person to smile. Does one side of the face droop or is it numb?

- A - Arm Weakness: Ask the person to raise both arms. Does one arm drift downward?

- S - Speech Difficulty: Ask the person to repeat a simple sentence. Is their speech slurred or strange? Can they understand you?

- T - Time to call Emergency: If you observe any of these signs, even if they disappear, call 911 (or your local emergency number) immediately. Time is brain.

Beyond FAST, other common signs and symptoms of stroke include:

- Sudden numbness or weakness of the leg, arm, or face, especially on one side of the body.

- Sudden confusion, trouble speaking, or difficulty understanding speech.

- Sudden trouble seeing in one or both eyes.

- Sudden trouble walking, dizziness, loss of balance, or lack of coordination.

- Sudden severe headache with no known cause (especially common in hemorrhagic stroke).

Specific Neurological Deficits and Correlation with Brain Regions:

The brain is highly specialized, so the location of the stroke dictates the specific neurological deficits observed.

A. Motor Deficits:

- Hemiparesis/Hemiplegia: Weakness (paresis) or paralysis (plegia) on one side of the body, contralateral to the side of the brain lesion. Affects the face, arm, and leg.

- Spasticity: Increased muscle tone, often developing weeks to months after the acute event, leading to stiffness and resistance to movement.

- Balance/Coordination Issues: Ataxia (lack of muscle control or coordination of voluntary movements), often seen in cerebellar strokes or brainstem involvement.

B. Sensory Deficits:

- Hemisensory Loss: Numbness, tingling, or reduced sensation on one side of the body, contralateral to the lesion.

- Altered Proprioception/Discriminative Touch: Difficulty sensing joint position or distinguishing between different textures.

C. Language Deficits (Aphasia):

- Aphasia refers to impaired communication due to brain damage, typically involving the dominant (usually left) hemisphere.

- Expressive Aphasia (Broca's Aphasia): Difficulty producing spoken or written language, even though understanding may be preserved. Speech is often slow, hesitant, and telegraphic.

- Receptive Aphasia (Wernicke's Aphasia): Difficulty understanding spoken or written language. Speech may be fluent but nonsensical (word salad).

- Global Aphasia: Severe impairment in both production and comprehension of language, often due to extensive damage in dominant hemisphere.

- Dysarthria: Difficulty with speech articulation due to weakness or lack of coordination of the muscles used for speech.

D. Vision Disturbances:

- Homonymous Hemianopsia: Loss of vision in the same half of the visual field in both eyes (e.g., cannot see anything to the left of midline with either eye), contralateral to the lesion.

- Diplopia: Double vision, often due to cranial nerve involvement.

- Amaurosis Fugax: Temporary, painless loss of vision in one eye ("curtain coming down"), often a symptom of carotid artery disease (TIA).

E. Cranial Nerve Deficits:

- Facial Palsy: Weakness or paralysis of facial muscles. In stroke, it typically affects the lower half of the face on the contralateral side (patient can still wrinkle forehead).

- Dysphagia: Difficulty swallowing, affecting safety of eating/drinking and increasing risk of aspiration.

- Dysarthria: (as above)

- Oculomotor Deficits: Ptosis (drooping eyelid), eye movement abnormalities.

F. Cognitive and Perceptual Deficits:

- Neglect (Hemispatial Neglect): Inattention to one side of the body or environment, typically the left side following a right hemisphere stroke. Patients may ignore food on one side of a plate, or deny ownership of a limb.

- Apraxia: Difficulty with skilled purposeful movements despite intact motor function (e.g., dressing apraxia).

- Agnosia: Inability to recognize familiar objects, persons, or sounds.

- Confusion/Disorientation: Especially in acute phases or with extensive damage.

- Memory Impairment: May be transient or permanent.

G. Headache, Nausea, Vomiting:

- While not always present in ischemic stroke, these symptoms are more common and often severe in hemorrhagic stroke, particularly with subarachnoid hemorrhage (thunderclap headache) or large intracerebral hemorrhages due to increased ICP.

H. Altered Level of Consciousness:

- Can range from mild confusion or drowsiness to stupor or coma, especially with large strokes, brainstem involvement, significant edema, or increased ICP.

I. Specific Stroke Syndromes (recap): The combination of these deficits defines the stroke syndrome, helping localize the lesion:

- MCA Stroke: Contralateral hemiparesis/sensory loss (face/arm > leg), aphasia (dominant), neglect (non-dominant).

- ACA Stroke: Contralateral hemiparesis/sensory loss (leg > arm), behavioral changes.

- PCA Stroke: Visual field defects (homonymous hemianopsia).

- Vertebrobasilar Stroke: Often presents with "Ds" – Dizziness, Diplopia, Dysarthria, Dysphagia, Dysmetria (ataxia). Can also include "crossed deficits" (e.g., facial sensory loss on one side, body motor weakness on the other).

Investigations & Diagnosis of Cerebral Vascular Accidents (Stroke)

The diagnostic process for stroke is a time-sensitive endeavor aimed at confirming the diagnosis, differentiating between ischemic and hemorrhagic types, identifying the underlying cause, and assessing the extent of brain damage. This multidisciplinary approach involves clinical assessment, neuroimaging, laboratory tests, and cardiovascular evaluation.

Initial Clinical Assessment:

Upon arrival at the emergency department, a rapid clinical assessment is performed to establish the probable diagnosis of stroke.

History Taking:

Physical and Neurological Examination:

- Level of Consciousness: Using Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS).

- Cranial Nerves: Assess pupils, eye movements, facial symmetry, swallowing.

- Motor System: Muscle strength (e.g., using NIH Stroke Scale), tone, coordination.

- Sensory System: Light touch, pain, proprioception.

- Speech and Language: Assess for aphasia, dysarthria.

- Balance and Gait: If applicable and safe.

Neuroimaging (The Cornerstone of Acute Stroke Diagnosis):

Neuroimaging is the most critical diagnostic tool for differentiating ischemic from hemorrhagic stroke and identifying the location and extent of damage.

A. Non-Contrast Computed Tomography (NCCT) Scan of the Brain:

- First-Line Imaging: Performed urgently (within minutes of ED arrival).

- Primary Goal: To rule out hemorrhage. Acute hemorrhage appears as hyperdense (bright white) areas on NCCT.

- Ischemic Stroke: Early signs of ischemia (e.g., loss of grey-white matter differentiation, sulcal effacement, hyperdense MCA sign) may be subtle or absent in the first few hours. Its main utility in early ischemic stroke is to exclude hemorrhage before administering thrombolytic agents.

B. CT Angiography (CTA) of Head and Neck:

- Purpose: Performed immediately after NCCT if ischemic stroke is suspected and the patient is a candidate for reperfusion therapy.

- Information Provided: Visualizes the cerebral vasculature (intracranial and extracranial arteries) to identify large vessel occlusion (LVO) which is a target for endovascular thrombectomy. Can also identify arterial dissections or aneurysms.

C. CT Perfusion (CTP):

- Purpose: Measures cerebral blood flow (CBF), cerebral blood volume (CBV), and mean transit time (MTT) in brain tissue.

- Information Provided: Helps to delineate the ischemic core (areas of irreversible damage) from the penumbra (at-risk but salvageable tissue). This information can extend the time window for thrombectomy in selected patients.

D. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of the Brain:

- Diffusion-Weighted Imaging (DWI): Highly sensitive for detecting acute ischemia (cytotoxic edema) within minutes of onset. Appears as hyperintense lesions.

- Apparent Diffusion Coefficient (ADC) Maps: Helps differentiate acute from chronic lesions.

- Fluid-Attenuated Inversion Recovery (FLAIR): Useful for distinguishing acute from chronic lesions (FLAIR abnormality often present after 4.5 hours) and for identifying white matter lesions.

- Gradient Echo (GRE) or Susceptibility-Weighted Imaging (SWI): Excellent for detecting hemorrhage (appears dark) and microbleeds.

- Magnetic Resonance Angiography (MRA): Similar to CTA, visualizes cerebral vessels to detect stenoses or occlusions.

- Magnetic Resonance Perfusion (MRP): Similar to CTP, helps identify penumbra.

Laboratory Tests:

- Complete Blood Count (CBC): To check for anemia, polycythemia, or infection.

- Basic Metabolic Panel (BMP): Electrolytes, renal function, glucose (hyperglycemia can worsen ischemic stroke outcomes).

- Coagulation Studies: Prothrombin Time (PT), International Normalized Ratio (INR), Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time (aPTT) – essential, especially if anticoagulants are used or considered.

- Cardiac Enzymes: To rule out concurrent myocardial infarction.

- Lipid Panel: To assess cholesterol levels (risk factor for atherosclerosis).

- Toxicology Screen: If illicit drug use is suspected.

- ESR/CRP: Inflammatory markers if vasculitis is suspected.

Cardiovascular Evaluation:

To identify cardiac sources of emboli or underlying cardiovascular disease.

A. Electrocardiogram (ECG):

- To detect atrial fibrillation, other arrhythmias, or signs of acute myocardial infarction.

B. Echocardiography (Transthoracic TTE or Transesophageal TEE):

- TTE: Evaluates heart chambers, valves, wall motion abnormalities, and left ventricular function. Can detect large thrombi.

- TEE: More sensitive than TTE for detecting cardiac sources of emboli, such as patent foramen ovale (PFO), atrial septal aneurysm, thrombi in the left atrial appendage, or valvular vegetations. Often performed in cryptogenic stroke workup.

C. Carotid Duplex Ultrasound:

- Purpose: Non-invasive assessment of the carotid arteries in the neck for stenosis (narrowing) due to atherosclerosis.

- Information Provided: Helps identify potential sources of artery-to-artery emboli or severe stenosis requiring surgical intervention (carotid endarterectomy) or stenting.

D. Holter Monitoring (24-48 hours or longer):

- Purpose: To detect paroxysmal (intermittent) atrial fibrillation, which can be a silent cause of cardioembolic stroke and may not be picked up on a single ECG.

Management of Cerebral Vascular Accident

Stroke management is a highly time-sensitive and multidisciplinary endeavor aimed at minimizing brain damage, preventing complications, promoting recovery, and preventing recurrence. It spans acute emergency care, inpatient rehabilitation, and long-term outpatient follow-up.

A. Acute Phase Management (Emergency Department & Intensive Care):

The primary goals in the acute phase are to stabilize the patient, restore blood flow in ischemic stroke, control bleeding in hemorrhagic stroke, and prevent secondary brain injury.

General Supportive Care:

- Airway: Assess for patency; intubation and mechanical ventilation if airway is compromised or GCS is low.

- Breathing: Oxygen supplementation to maintain SpO2 >94%.

- Circulation: Maintain adequate blood pressure; avoid hypotension.

- Ischemic Stroke: Permissive hypertension (BP up to 220/120 mmHg) is generally allowed in patients not receiving thrombolytics, as higher pressure may be needed to perfuse the ischemic penumbra. If thrombolytics are given, BP must be tightly controlled (<185/110 mmHg pre-treatment, and <180/105 mmHg for 24 hours post-treatment) to prevent hemorrhagic transformation.

- Hemorrhagic Stroke: Aggressive BP control is often necessary to prevent hematoma expansion (target typically <140-160 mmHg systolic).

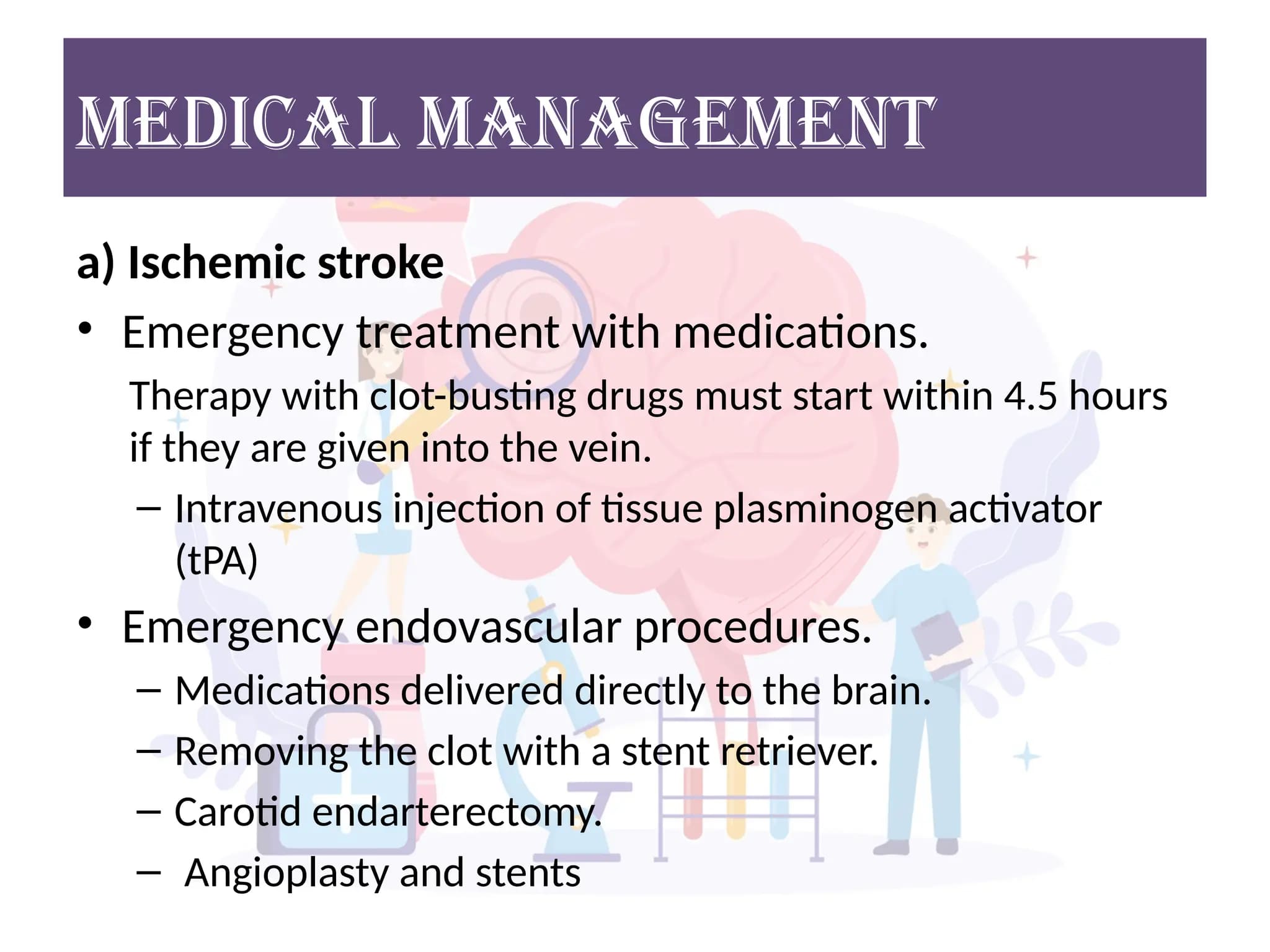

Specific Management for Ischemic Stroke:

A. Reperfusion Therapies: Time is brain – these therapies aim to restore blood flow to the ischemic penumbra.

- Mechanism: Administered intravenously to dissolve the clot blocking the artery.

- Time Window: Approved for administration within 4.5 hours of symptom onset (with stricter criteria for 3-4.5 hours).

- Eligibility: Strict inclusion/exclusion criteria must be met (e.g., age, stroke severity, recent surgery, history of hemorrhage).

- Monitoring: Close neurological and blood pressure monitoring post-tPA due to risk of hemorrhagic transformation.

- Mechanism: A catheter is inserted into an artery (usually femoral) and guided to the brain to mechanically remove the clot.

- Time Window: Approved for up to 6 hours for large vessel occlusions (LVOs) in the anterior circulation. In carefully selected patients (based on perfusion imaging to identify salvageable penumbra), the window can be extended up to 24 hours.

- Eligibility: Indicated for LVOs in anterior circulation; often used in conjunction with IV tPA if eligible.

B. Antiplatelet Therapy:

- Aspirin: For patients not eligible for tPA or thrombectomy, early aspirin (within 24-48 hours) is recommended to reduce the risk of early recurrence.

- Dual Antiplatelet Therapy (DAPT): For minor stroke or TIA, aspirin plus clopidogrel may be used for a short duration (e.g., 21-90 days) to reduce early recurrent stroke risk.

3. Specific Management for Hemorrhagic Stroke:

A. Intracerebral Hemorrhage (ICH):

- Blood Pressure Control: Aggressive and rapid lowering of systolic BP to 140-160 mmHg is crucial to prevent hematoma expansion, provided it does not compromise cerebral perfusion.

- Reversal of Anticoagulation: If the patient is on anticoagulants (e.g., warfarin, DOACs), immediate reversal agents are administered (e.g., Vitamin K, prothrombin complex concentrate (PCC), idarucizumab, andexanet alfa).

- Surgical Evacuation: May be considered for certain cases, such as large cerebellar hemorrhages causing brainstem compression, rapidly deteriorating neurological status, or large lobar hemorrhages with accessible clots.

- ICP Monitoring and Management: If there's evidence of significant mass effect or hydrocephalus, ICP monitoring and interventions (e.g., external ventricular drain, osmotherapy) may be needed.

B. Subarachnoid Hemorrhage (SAH):

- Secure Aneurysm: The primary goal is to prevent re-bleeding from the ruptured aneurysm.

- Endovascular Coiling: A catheter is used to place platinum coils into the aneurysm to occlude it.

- Surgical Clipping: A neurosurgeon places a small clip at the neck of the aneurysm to block blood flow.

- Nimodipine: A calcium channel blocker, administered orally, to prevent or reduce delayed cerebral ischemia due to vasospasm.

- Strict Blood Pressure Control: To prevent re-bleeding (usually systolic <160 mmHg).

- Management of Complications: Hydrocephalus (EVD), vasospasm (nimodipine, induced hypertension, angioplasty).

B. Post-Acute Phase Management (Hospital Ward & Rehabilitation):

Once stabilized, the focus shifts to preventing complications, initiating rehabilitation, and planning for secondary prevention.

1. Prevention of Complications:

- Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT) & Pulmonary Embolism (PE): Early mobilization, graduated compression stockings, intermittent pneumatic compression devices, and pharmacological prophylaxis (e.g., low-molecular-weight heparin) are crucial.

- Pneumonia: Aspiration pneumonia is common, especially with dysphagia. Early dysphagia screening, swallow evaluation, and maintaining oral hygiene are vital.

- Pressure Ulcers: Regular repositioning, skin care, and specialized mattresses.

- Urinary Tract Infections (UTIs): Avoid indwelling catheters if possible; meticulous perineal care.

- Depression/Anxiety: Common after stroke; screening and appropriate treatment (counseling, medication) are important.

2. Rehabilitation:

- Early Initiation: Rehabilitation should begin as soon as the patient is medically stable (often within 24-48 hours).

- Multidisciplinary Team: Involves physical therapists (PT), occupational therapists (OT), speech-language pathologists (SLP), physiatrists (rehabilitation physicians), neuropsychologists, and social workers.

- Goals: Maximize functional recovery, improve independence in activities of daily living (ADLs), and facilitate community reintegration.

- Settings: Acute rehabilitation units, skilled nursing facilities, outpatient rehabilitation, home-based therapy.

3. Secondary Prevention:

Addressing modifiable risk factors is paramount to prevent recurrent stroke.

- Blood Pressure Control: Lifelong management (target often <130/80 mmHg).

- Lipid Management: Statin therapy regardless of cholesterol levels to stabilize plaques and reduce inflammation.

- Diabetes Management: Strict glycemic control.

- Antiplatelet Agents: (e.g., aspirin, clopidogrel, aspirin + extended-release dipyridamole) for most ischemic stroke patients (unless AFib).

- Anticoagulation: For patients with atrial fibrillation or other high-risk cardioembolic sources (e.g., warfarin, DOACs).

- Smoking Cessation: Counseling and support.

- Diet and Exercise: Healthy lifestyle recommendations.

- Carotid Artery Revascularization: Carotid endarterectomy or stenting for severe symptomatic carotid stenosis.

- Lifestyle Modifications: Weight management, moderate alcohol intake.

Nursing Care in Stroke Management:

Nurses play a continuous and vital role throughout the entire stroke continuum.

Acute Phase:

- Rapid Assessment & Recognition: Using stroke scales (NIHSS).

- Vital Sign Monitoring: BP, HR, O2 Sat, Temp, neurological status (GCS, pupil checks).

- Medication Administration: IV tPA, BP control agents, antiplatelets, etc., with careful monitoring for side effects (e.g., bleeding with tPA).

- Preparation for Imaging/Procedures: Ensuring patient safety and readiness.

- Airway Management: Suctioning, oxygen delivery.

- Dysphagia Screening: To prevent aspiration.

- Patient and Family Education: Explaining the condition, treatment plan, and expectations.

Post-Acute & Rehabilitation Phase:

- Mobility & Positioning: Preventing complications like DVT, pressure ulcers, contractures.

- Bladder and Bowel Management: To prevent UTIs and maintain dignity.

- Skin Integrity: Regular assessment and care.

- Nutritional Support: Assisting with feeding, managing enteral tubes if necessary.

- Medication Management: Ensuring adherence and monitoring side effects.

- Emotional Support: Addressing depression, anxiety, frustration.

- Reinforcing Therapy: Working with PT, OT, SLP to integrate exercises and strategies into daily care.

- Discharge Planning: Coordinating with the multidisciplinary team for appropriate placement and resources.

Prognosis & Complications

The prognosis following a stroke varies widely, depending on numerous factors including stroke type, severity, location, age, comorbidities, and the timeliness and effectiveness of acute treatment and rehabilitation. While some individuals experience a full recovery, many live with long-term disabilities and face various complications.

A. Factors Influencing Prognosis:

- Stroke Severity: Measured by scales like the NIHSS. Lower initial scores generally correlate with better outcomes.

- Stroke Type: Ischemic strokes generally have a better prognosis than large hemorrhagic strokes, which often carry higher morbidity and mortality.

- Stroke Location & Size: Small lacunar strokes often have a better functional prognosis than large cortical strokes or brainstem strokes.

- Age: Younger patients generally have greater neuroplasticity and recovery potential.

- Premorbid Functional Status: Individuals with good health and function before the stroke tend to recover better.

- Comorbidities: Pre-existing conditions like diabetes, heart disease, and chronic kidney disease can negatively impact recovery.

- Timeliness of Treatment: Rapid access to acute reperfusion therapies (tPA, thrombectomy) significantly improves outcomes in ischemic stroke.

- Quality and Intensity of Rehabilitation: Early and intensive multidisciplinary rehabilitation is crucial for maximizing functional recovery.

- Social Support: Strong family and social support systems are associated with better long-term adjustment and recovery.

- Recurrent Stroke: The occurrence of another stroke significantly worsens prognosis.

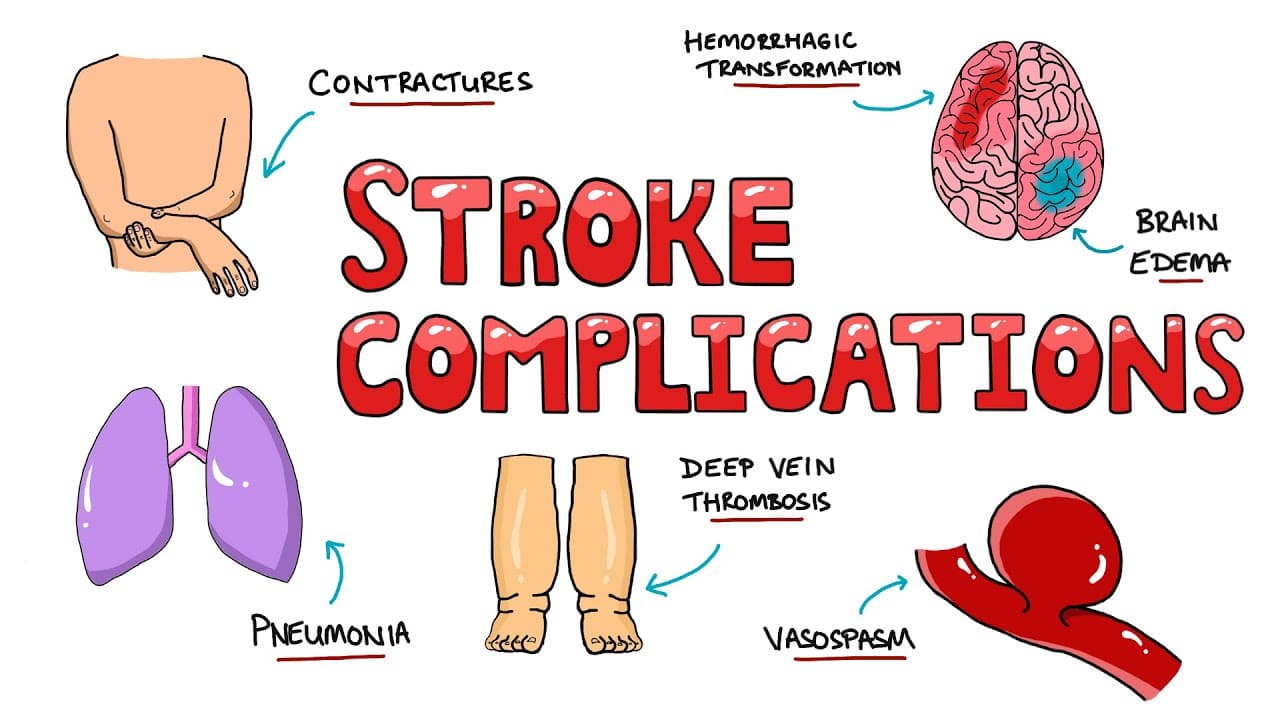

B. Common Complications of Stroke:

Stroke survivors are prone to a range of physical, cognitive, and emotional complications, which can further impact their quality of life and functional independence.

1. Neurological Complications:

- Recurrent Stroke: The most feared complication. The risk is highest in the first few days and weeks after the initial event. Secondary prevention is paramount.

- Post-Stroke Epilepsy/Seizures: Can occur acutely or much later, especially after cortical strokes or hemorrhagic strokes.

- Cerebral Edema: Swelling of brain tissue, which can lead to increased intracranial pressure (ICP), brain herniation, and further damage. More common with large strokes.

- Hemorrhagic Transformation: An ischemic stroke can convert into a hemorrhagic stroke, especially after thrombolytic therapy or with large infarcts.

- Hydrocephalus: More common after subarachnoid hemorrhage, but can occur after ICH due to obstruction of CSF flow.

- Spasticity & Contractures: Increased muscle tone and shortening of muscles/tendons, leading to stiffness and limited range of motion, often affecting the paretic limbs.

- Central Post-Stroke Pain (CPSP): Chronic neuropathic pain that results from damage to the central nervous system.

- Vascular Cognitive Impairment (VCI) / Post-Stroke Dementia: A decline in cognitive function ranging from mild to severe, often due to damage to critical brain regions or widespread small vessel disease.

- Post-Stroke Fatigue: Profound and debilitating fatigue that is disproportionate to activity level.

2. Systemic Medical Complications:

- Aspiration Pneumonia: Common due to dysphagia and impaired cough reflex. A leading cause of death after stroke.

- Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT) & Pulmonary Embolism (PE): Due to immobility and hypercoagulability. PE is a significant cause of mortality.

- Urinary Tract Infections (UTIs): Often associated with urinary incontinence, catheterization, and impaired bladder emptying.

- Pressure Ulcers (Bedsores): Due to immobility and impaired sensation.

- Cardiac Complications: Post-stroke myocardial infarction, arrhythmias (e.g., new-onset AFib), heart failure exacerbation.

- Malnutrition/Dehydration: Especially in patients with severe dysphagia or impaired consciousness.

3. Psychological and Emotional Complications:

- Post-Stroke Depression (PSD): Very common, affecting up to one-third of stroke survivors. Can significantly impair rehabilitation and quality of life.

- Anxiety Disorders: Generalized anxiety, panic attacks, or specific phobias.

- Emotional Lability/Pseudobulbar Affect (PBA): Uncontrollable and often inappropriate episodes of laughing or crying.

- Apathy: Lack of motivation or interest in activities.

- Frustration/Anger: Common reactions to loss of function and independence.

4. Social and Functional Complications:

- Functional Dependence: Difficulty with Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) such as bathing, dressing, eating, and mobility.

- Social Isolation: Difficulty participating in social activities, returning to work, or maintaining hobbies.

- Caregiver Burden: The significant physical, emotional, and financial strain on family members providing care.

- Financial Strain: Due to healthcare costs, loss of income, and need for assistive devices or home modifications.

C. Recovery Trajectory:

- Most Rapid Recovery: Occurs in the first 3-6 months post-stroke, driven by neuroplasticity and intensive rehabilitation.

- Continued Improvement: Can occur for up to a year or longer, though at a slower pace.

- Plateau: Many individuals reach a plateau in their recovery, but ongoing therapy and compensatory strategies can still improve function and quality of life.

- Long-Term Needs: Many stroke survivors require ongoing physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy, and psychological support for years after their stroke.

Prevention & Public Health

Stroke is largely preventable, and significant reductions in its incidence and burden can be achieved through effective public health initiatives and individual lifestyle modifications. Prevention strategies are broadly categorized into primary (preventing the first stroke) and secondary (preventing recurrent stroke) prevention.

A. Primary Prevention (Preventing the First Stroke):

Primary prevention targets modifiable risk factors within the general population.

1. Lifestyle Modifications:

- Reduced Sodium Intake: Essential for blood pressure control.

- Increased Fruits, Vegetables, and Whole Grains: Provide fiber, vitamins, and antioxidants.

- Lean Protein Sources: Fish, poultry, legumes.

- Limiting Saturated and Trans Fats, Cholesterol: To manage dyslipidemia and atherosclerosis.

- DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) or Mediterranean Diet: Evidence-based dietary patterns known to reduce stroke risk.

- Aim for at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity aerobic activity per week, plus muscle-strengthening activities at least two days a week.

- Helps manage blood pressure, weight, diabetes, and cholesterol.

- Achieving and maintaining a healthy body weight (BMI between 18.5-24.9 kg/m²) reduces the risk of hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia.

- Smoking is a major independent risk factor for stroke, causing damage to blood vessels and increasing clotting risk. Cessation significantly reduces risk, with benefits seen rapidly.

- Excessive alcohol intake increases blood pressure and risk of atrial fibrillation. Moderate intake (up to one drink per day for women, up to two for men) may be acceptable, but less is generally better.

2. Medical Management of Modifiable Risk Factors:

- Screening: Regular blood pressure checks are crucial.

- Treatment: Lifestyle modifications and antihypertensive medications (e.g., diuretics, ACE inhibitors, ARBs, calcium channel blockers, beta-blockers) to achieve target blood pressure (typically <130/80 mmHg for most adults). This is the most important modifiable risk factor.

- Screening: Regular blood glucose checks.

- Treatment: Diet, exercise, and antidiabetic medications (oral agents, insulin) to maintain optimal glycemic control (HbA1c <7%).

- Screening: Lipid panel.

- Treatment: Lifestyle changes and statin medications to lower LDL cholesterol, which reduces atherosclerotic plaque formation.

- Screening: Regular pulse checks, ECGs.

- Treatment: Anticoagulation (e.g., warfarin, direct oral anticoagulants/DOACs) to prevent clot formation and embolization, based on individual CHA2DS2-VASc score.

- Screening: May be considered in high-risk individuals; carotid ultrasound.

- Treatment: Antiplatelet therapy, statins, blood pressure control. Carotid endarterectomy or stenting for severe, symptomatic stenosis.

B. Secondary Prevention (Preventing Recurrent Stroke):

Secondary prevention focuses on individuals who have already experienced a TIA or stroke, aiming to prevent subsequent events.

- Ischemic Stroke/TIA: Aspirin, clopidogrel, or a combination (e.g., aspirin + extended-release dipyridamole, or short-term dual antiplatelet therapy for minor stroke/high-risk TIA).

- For cardioembolic stroke (e.g., due to AFib, mechanical heart valves), lifelong anticoagulation with warfarin or DOACs is crucial.

- Recommended for all patients with ischemic stroke/TIA of atherosclerotic origin, regardless of baseline cholesterol levels, due to their pleiotropic effects (plaque stabilization, anti-inflammatory).

- Aggressive management of hypertension to target levels (e.g., <130/80 mmHg).

C. Public Health Initiatives:

- "FAST" Campaign: Educating the public about the signs and symptoms of stroke and the importance of rapid emergency response.

- Risk Factor Education: Promoting awareness of modifiable risk factors and the benefits of healthy lifestyles.

- Development of Stroke Centers: Designated primary and comprehensive stroke centers with specialized expertise, equipment, and protocols for rapid stroke diagnosis and treatment.

- Emergency Medical Services (EMS) Protocols: Training EMS personnel to identify stroke, triage appropriately, and transport patients to the nearest qualified stroke center.

- Tobacco Control: Policies to reduce smoking rates.

- Healthy Food Environments: Promoting access to nutritious food options.

- Physical Activity Promotion: Creating safe environments for physical activity.

- Ongoing research into new prevention strategies, treatments, and rehabilitation techniques.

- Monitoring stroke incidence, prevalence, and outcomes to identify trends and evaluate the effectiveness of interventions.