Table of Contents

ToggleIntroduction to Poliomyelitis

Poliomyelitis, commonly known as polio, is an infectious disease that has historically caused widespread fear due to its potential for causing permanent paralysis and death, particularly in children. While significant progress has been made towards its global eradication, understanding the disease remains crucial for healthcare professionals and public health initiatives. This section will introduce the disease, its causative agent, and its epidemiology.

Poliomyelitis is derived from the Greek words "polios" (meaning gray), "myelon" (meaning marrow, referring to the spinal cord), and "-itis" (meaning inflammation). Therefore, literally, poliomyelitis refers to the "inflammation of the gray matter of the spinal cord."

- Nature of the Disease: Polio is an acute, highly contagious viral infection.

- Causative Agent: It is caused by the poliovirus.

- Primary Target: While the virus initially replicates in the gastrointestinal tract, its most severe clinical manifestations arise from its invasion and damage to the central nervous system (CNS), specifically the motor neurons in the anterior horn of the spinal cord and the brainstem.

- Clinical Spectrum: The infection can manifest in various ways, ranging from asymptomatic infection (which is the most common outcome) to severe paralytic disease, which is the most feared and recognized form.

- Historical Context: Prior to the development of effective vaccines in the mid-20th century, polio epidemics were a regular and terrifying occurrence worldwide, earning it the moniker "infantile paralysis" due to its predilection for affecting young children.

- Impact: The long-term consequences of paralytic polio include permanent muscle weakness, paralysis, skeletal deformities, and in severe cases involving respiratory muscles, death.

The Causative Agent: Poliovirus

The agent responsible for poliomyelitis is the poliovirus (PV), a highly adapted human pathogen.

Classification:

- Family: Picornaviridae (Pico = small, RNA = RNA virus).

- Genus: Enterovirus (Enteron = intestine), indicating its primary site of replication and excretion.

Viral Structure: Poliovirus is a small, non-enveloped RNA virus. The absence of an outer lipid envelope makes it particularly stable and resistant to environmental factors such as disinfectants, detergents, and acidic conditions (like stomach acid). This resilience contributes to its efficient fecal-oral transmission.

Genomic Material: Its genetic material is a single-stranded positive-sense RNA genome.

Serotypes (Immunological Types):

There are three distinct immunological types (serotypes) of wild poliovirus (WPV), designated as Type 1, Type 2, and Type 3. These serotypes are antigenically distinct, meaning that immunity to one type does not confer significant protection against the other two. Therefore, effective vaccination requires protection against all three serotypes.

Wild Poliovirus Type 1 (WPV1):

- Significance: WPV1 is historically the most common cause of paralytic polio and the serotype that currently poses the greatest threat to global eradication efforts.

- Status: It remains endemic in the last two polio-endemic countries (Afghanistan and Pakistan) and is responsible for all recent outbreaks of wild poliovirus.

Wild Poliovirus Type 2 (WPV2):

- Significance: WPV2 was successfully eradicated globally, with the last naturally occurring case confirmed in India in 1999.

- Declaration: It was formally certified as eradicated in September 2015.

- Vaccine Impact: Due to its eradication, and to minimize the risk of vaccine-associated paralytic polio (VAPP) and circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus (cVDPV) linked specifically to the Type 2 component of the Oral Polio Vaccine (OPV), the Type 2 component was removed from routine OPV use in a synchronized global switch in April 2016 (moving from trivalent OPV to bivalent OPV containing only Type 1 and Type 3).

Wild Poliovirus Type 3 (WPV3):

- Significance: WPV3 was also successfully eradicated globally, with the last naturally occurring case confirmed in Nigeria in 2012.

- Declaration: It was formally certified as eradicated in October 2019.

- Vaccine Impact: Following its eradication, the Type 3 component of OPV was also eventually phased out, leaving only Type 1 in the final stages of the eradication strategy where OPV is still used.

The successful eradication of WPV2 and WPV3 represents monumental achievements in public health, demonstrating the feasibility of global disease eradication. The ongoing challenge is to achieve the same for WPV1.

Epidemiology of Polio

Understanding the epidemiology of poliovirus is fundamental to designing and implementing effective control and eradication strategies.

A. Mode of Transmission:

Poliovirus is highly contagious and primarily spreads through:

- Poor sanitation.

- Inadequate hand hygiene.

- Contaminated water sources (e.g., sewage leakage into drinking water).

- Contaminated food prepared by an infected individual.

B. Reservoirs:

- Humans Only: A critical factor in the feasibility of polio eradication is that humans are the only known natural reservoir for poliovirus. Unlike many other diseases that can hide in animal populations, if the virus is eliminated from all humans, it has nowhere else to persist naturally. This makes global eradication a realistic, albeit challenging, goal.

C. Historical Global Prevalence:

- Widespread Before Vaccination: Prior to the widespread availability of polio vaccines in the mid-1950s (Salk's IPV) and early 1960s (Sabin's OPV), polio was endemic worldwide.

- Epidemics: It caused devastating epidemics, particularly in developed countries where improved sanitation ironically led to a later age of exposure (children had less passive immunity from mothers) and thus a higher risk of paralytic disease.

- Seasonal Pattern: In temperate climates, polio epidemics often occurred during the summer and fall months.

- Public Fear: The disease instilled immense fear, leading to significant public health campaigns and a desperate search for a cure and prevention. It filled hospitals with paralyzed children and led to the widespread use of "iron lungs" for patients with respiratory paralysis.

D. Current Restricted Geographical Distribution:

- Dramatic Reduction: The Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI), launched in 1988, has resulted in a dramatic reduction in polio cases (over 99.9% reduction) and a severe constriction of the geographical range of the wild poliovirus.

- Endemic Countries (as of current status): As previously noted, Wild Poliovirus Type 1 (WPV1) is currently endemic in only two countries:

- Afghanistan

- Pakistan

- Circulating Vaccine-Derived Poliovirus (cVDPV): While WPV has been largely confined, a new challenge has emerged: circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus (cVDPV). This occurs in areas with low population immunity where the weakened virus from the oral polio vaccine (OPV) can circulate for a prolonged period, mutate, and regain neurovirulence, behaving like wild poliovirus. cVDPV outbreaks are a growing concern in several countries across Africa and Asia, underscoring the importance of high vaccination coverage.

- Imported Cases: Even countries declared polio-free can experience imported cases of WPV from the endemic countries, or cVDPV, necessitating robust surveillance systems.

E. Silent Transmission by Asymptomatic Carriers:

- The "Iceberg" Phenomenon: For every case of paralytic polio, there are hundreds, if not thousands, of individuals who are infected with the poliovirus but show no symptoms (asymptomatic carriers) or only mild, non-specific symptoms.

- Public Health Challenge: These asymptomatic carriers are highly infectious and effectively shed the virus, silently spreading it within communities. This "silent transmission" is a major epidemiological challenge, as it means the virus is circulating far more widely than clinical cases would suggest. This necessitates population-wide vaccination campaigns and highly sensitive environmental surveillance (e.g., testing sewage samples) to detect virus circulation in the absence of reported paralysis.

Pathophysiology of Poliovirus Infection

The journey of the poliovirus through the human body is critical to understanding the wide spectrum of clinical outcomes, from unapparent infection to devastating paralysis.

A. Viral Entry and Initial Replication:

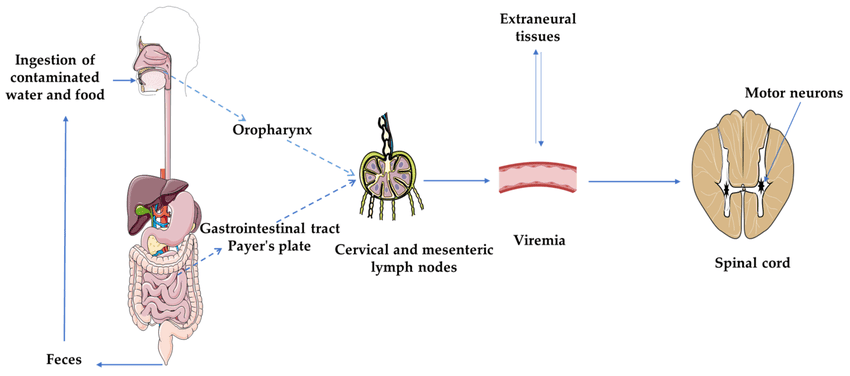

- Entry: Poliovirus primarily enters the body through the mouth, usually via ingestion of contaminated food or water (fecal-oral route).

- Primary Replication Sites:

- Oropharynx: The virus initially replicates in the lymphoid tissues of the oropharynx (tonsils, Peyer's patches).

- Gastrointestinal Tract: It then moves down to the Peyer's patches and other lymphoid tissues of the small intestine. During this stage, the virus is shed in throat secretions for a short period and in feces for several weeks.

- Viremia (Minor and Major):

- Minor Viremia: From the primary replication sites, the virus enters the bloodstream, leading to a transient, low-level viremia. In most cases (about 95-99%), the infection is contained at this stage, and the host's immune system clears the virus, resulting in asymptomatic infection or mild illness.

- Major Viremia: In a small percentage of cases (1-5%), the virus continues to replicate in lymphoid tissue and spreads to other tissues, including deeper lymph nodes, brown fat, and muscle. This leads to a sustained, higher-level viremia. It is from this major viremia that the virus gains access to the central nervous system.

B. Invasion of the Central Nervous System (CNS):

- Blood-Brain Barrier: Poliovirus gains access to the CNS by crossing the blood-brain barrier. The exact mechanism is not fully understood but is thought to involve transport across endothelial cells or via infected macrophages.

- Neural Pathways: Once in the bloodstream, the virus can also travel along peripheral nerves to reach the CNS. This "retrograde axonal transport" from infected peripheral sites to the spinal cord is another proposed pathway.

- Target Cells - Motor Neurons: Within the CNS, poliovirus has a distinct tropism (preference) for motor neurons. These are the nerve cells responsible for transmitting signals from the brain and spinal cord to muscles, initiating movement. The virus primarily attacks:

- Anterior Horn Cells (AHC) of the Spinal Cord: These are the motor neurons that control skeletal muscle movement.

- Motor Nuclei of the Brainstem: Affecting cranial nerves that control facial muscles, swallowing, and breathing.

- Destruction of Neurons: The poliovirus replicates within these motor neurons, leading to their destruction (lytic infection). This neuronal death is the direct cause of paralysis.

- Inflammation: The destruction of neurons triggers an inflammatory response in the surrounding tissues, contributing to the acute symptoms (pain, stiffness).

C. Clinical Forms of Polio Infection:

The outcome of poliovirus infection is highly variable, largely depending on whether the virus successfully invades the CNS and which parts it affects.

- Asymptomatic (Inapparent) Infection (90-95% of cases):

- Description: The vast majority of individuals infected with poliovirus experience no symptoms whatsoever.

- Pathophysiology: The virus replicates in the GI tract, and minor viremia occurs, but the immune system effectively clears the virus before it can reach or cause significant damage in the CNS.

- Clinical Significance: These individuals are crucial for viral transmission as they shed the virus in their feces, contributing to the "silent spread" of polio within a population.

- Abortive Polio (Minor Illness) (4-8% of cases):

- Description: A mild, non-specific illness lasting a few days, without evidence of CNS involvement.

- Pathophysiology: The infection progresses to major viremia, causing systemic symptoms, but the immune response is robust enough to prevent CNS invasion.

- Symptoms: Fever, malaise, headache, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, sore throat. These symptoms are indistinguishable from other common viral infections.

- Non-Paralytic Aseptic Meningitis (1-2% of cases):

- Description: The virus invades the CNS, causing inflammation of the meninges (the membranes surrounding the brain and spinal cord), but without motor neuron destruction leading to paralysis.

- Pathophysiology: Poliovirus enters the CNS, triggering an inflammatory response, but motor neurons are either not infected or not extensively damaged.

- Symptoms: In addition to abortive polio symptoms, patients experience signs of meningeal irritation: stiff neck, back pain, muscle spasm, and sometimes a skin rash. Recovery is usually complete within 2-10 days. Diagnosis is confirmed by CSF analysis showing elevated white blood cells (predominantly lymphocytes) and normal glucose.

- Paralytic Polio (Less than 1% of cases):

- Description: This is the most severe and feared form, characterized by muscle weakness and irreversible paralysis, resulting from the destruction of motor neurons in the CNS.

- Pathophysiology: The virus replicates extensively in motor neurons of the spinal cord and/or brainstem, leading to their irreversible destruction. The extent and location of neuronal damage determine the pattern and severity of paralysis.

- Phases:

- Prodromal Phase: Often preceded by an abortive illness or aseptic meningitis.

- Major Illness: Characterized by a new wave of fever, severe muscle pain, spasms, and the rapid onset of flaccid paralysis.

- Clinical Significance: This is the form that leads to long-term disability and death.

Clinical Manifestations of Paralytic Polio

Paralytic polio is a devastating condition with a distinct clinical picture.

A. General Signs and Symptoms of Acute Paralytic Polio:

The onset of paralysis is typically preceded by a prodromal phase (fever, headache, nausea, vomiting) followed by a return of fever and other more severe symptoms.

- Fever: Often biphasic (an initial fever followed by a period of relative normalcy, then a second, higher fever coinciding with paralysis onset).

- Fatigue and Malaise: General feeling of unwellness.

- Headache: Can be severe.

- Nausea and Vomiting: Common, particularly in the prodromal phase.

- Stiffness and Pain: Characteristically, patients develop severe muscle pain and spasms, particularly in the back, neck, and limbs. Stiffness of the neck and back (nuchal rigidity) is a common sign of meningeal irritation.

- Muscle Tenderness: Muscles are often exquisitely tender to touch.

- Rapid Onset of Paralysis: The hallmark of paralytic polio is the sudden, usually rapid (within hours to a few days) onset of muscle weakness progressing to paralysis.

- Characteristic Paralysis:

- Flaccid: The muscles are weak and limp, with reduced or absent reflexes (areflexia). This differentiates it from spastic paralysis (which involves increased muscle tone).

- Asymmetric: The paralysis typically affects one side of the body more than the other, or one limb more than another. It is rarely symmetrical.

- Proximal > Distal: Often affects proximal muscles (e.g., thigh, shoulder) more severely than distal muscles (e.g., foot, hand).

- Lower Limbs > Upper Limbs: Paralysis is more common and often more severe in the legs than in the arms.

B. Patterns of Paralysis:

The pattern of paralysis depends on which motor neurons in the CNS are primarily affected.

- Description: This form results from the destruction of motor neurons in the anterior horn of the spinal cord.

- Clinical Features: Characterized by asymmetric flaccid paralysis affecting the muscles innervated by the damaged spinal cord segments. This most commonly affects the lower limbs, but can also affect the arms, trunk, and diaphragm.

- Respiratory Involvement: Paralysis of the intercostal muscles and diaphragm can lead to respiratory failure, historically requiring mechanical ventilation ("iron lung").

- Description: This form occurs when the poliovirus attacks the motor nuclei of the cranial nerves located in the brainstem (the "bulb" of the brain).

- Clinical Features: Affects the muscles supplied by cranial nerves, leading to:

- Dysphagia: Difficulty swallowing (due to paralysis of pharyngeal and laryngeal muscles), increasing the risk of aspiration.

- Dysphonia/Aphonia: Difficulty speaking or loss of voice.

- Facial Weakness: Asymmetric paralysis of facial muscles.

- Respiratory Difficulties: Impairment of breathing and heart regulation centers in the brainstem, which can lead to rapid and severe respiratory failure and cardiac arrest. This is the most dangerous form, with a higher mortality rate.

- Description: A combination of both spinal and bulbar paralysis, affecting both the limbs and the cranial nerve-innervated muscles.

- Clinical Features: Patients present with symptoms of both spinal and bulbar polio, making this a particularly severe and life-threatening form. Respiratory compromise is very common.

C. Outcome of Paralysis:

- Variable Recovery: The paralysis is typically maximal within a few days of onset. Some degree of motor function can return over weeks to months as uninjured neurons recover or collateral sprouting occurs. However, any motor neurons that are destroyed cannot be replaced, leading to permanent weakness or paralysis in the affected muscles.

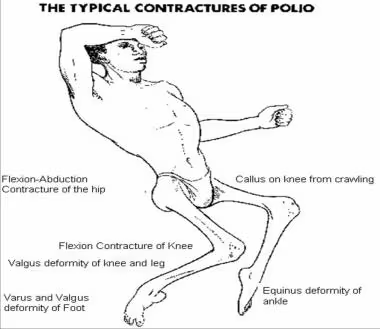

- Permanent Disability: Long-term consequences include muscle atrophy, limb deformities, joint contractures, and functional limitations requiring assistive devices (braces, wheelchairs) or surgery.

- Mortality: Mortality rates for paralytic polio vary but are higher in bulbar polio (5-10%) and can be up to 25-75% if respiratory muscles are involved and ventilatory support is unavailable.

Discussion of the Diagnosis of Polio

Accurate and timely diagnosis of poliovirus infection, particularly paralytic polio, is crucial for patient management, public health surveillance, and confirming cases within the context of eradication efforts. Given the rarity of wild poliovirus today, differentiating polio from other causes of acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) is a primary diagnostic challenge.

A. Clinical Suspicion:

- Diagnosis often begins with clinical suspicion, especially in areas where polio is still endemic or where there are outbreaks of vaccine-derived poliovirus.

- Any case of Acute Flaccid Paralysis (AFP), especially in a child under 15 years, must be investigated for polio. AFP is defined as the sudden onset of flaccid paralysis (loss of muscle tone) in one or more limbs, often accompanied by loss of deep tendon reflexes, in a child.

- Key Clinical Features Suggestive of Polio: Rapid onset of asymmetric flaccid paralysis with absent deep tendon reflexes, absence of sensory loss, and fever at onset.

B. Laboratory Confirmation (Gold Standard):

Confirmation of poliovirus infection primarily relies on the detection and identification of the virus itself or specific antibodies.

- Specimen Collection:

- Stool Samples: This is the most important and reliable specimen for poliovirus isolation. Two stool samples (8-10g each) should be collected 24-48 hours apart, as early as possible after the onset of paralysis (within 14 days), and kept refrigerated. The virus is shed in feces for several weeks.

- Throat Swabs: Can be collected early in the course of illness (within the first few days) as the virus replicates in the oropharynx, but stool samples are generally more productive.

- Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF): Poliovirus can be isolated from CSF in a small percentage of paralytic cases, but it is not the primary diagnostic sample due to lower viral load and difficulty in collection.

- Environmental Samples (Sewage): Used for surveillance to detect the presence of poliovirus in communities, even in the absence of reported cases.

- Procedure:

- RT-PCR: Initially, nucleic acid amplification tests like RT-PCR are used to detect poliovirus RNA. This provides rapid results.

- Cell Culture: Positive PCR samples are then typically cultured on susceptible cell lines (e.g., L20B cells) to isolate the live virus. This allows for further characterization.

- Serotyping: Once isolated, the virus is identified as wild poliovirus (WPV1, WPV2, WPV3) or vaccine-derived poliovirus (VDPV) using specific serological tests and genetic sequencing. Genetic sequencing is critical to differentiate between wild types and VDPVs, and to trace the origin of outbreaks.

- Interpretation: Isolation of poliovirus from stool samples in a case of AFP is definitive evidence of polio.

- Method: Measures the presence and levels of antibodies (IgM, IgG) against poliovirus in the blood.

- Significance:

- IgM: Elevated IgM antibodies indicate recent infection.

- Paired Sera (IgG): A four-fold or greater rise in neutralizing antibody titers between acute and convalescent serum samples (taken 3-4 weeks apart) is indicative of recent infection.

- Limitations: Serology alone can be less specific than viral isolation for acute diagnosis as it cannot differentiate between infection due to wild virus, vaccine virus, or previous vaccination unless the patient is completely unvaccinated. It's more useful for assessing population immunity levels or confirming exposure in retrospect.

C. Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) Analysis (Importance in Suspected Cases):

- Procedure: A lumbar puncture is performed to collect CSF.

- Findings in Polio:

- Early Stage (First few days): Elevated white blood cell count (pleocytosis), predominantly polymorphonuclear leukocytes (neutrophils), with mildly elevated protein.

- Later Stage (After first week): White blood cells become predominantly lymphocytes, and protein levels may be more elevated. Glucose levels are usually normal.

- Diagnostic Value: CSF analysis helps in differentiating polio from other neurological conditions (e.g., bacterial meningitis, which would show low glucose and predominantly neutrophils, or Guillain-Barré Syndrome, which typically shows high protein with few or no cells—albumino-cytological dissociation). While not diagnostic for poliovirus by itself, it provides supportive evidence of CNS inflammation and helps rule out other causes of AFP.

D. Differential Diagnosis for Acute Flaccid Paralysis (AFP):

It's important to remember that poliovirus is only one cause of AFP. Other conditions that can present with AFP include:

- Guillain-Barré Syndrome (GBS)

- Transverse Myelitis

- Acute Myelitis caused by other viruses (e.g., Enterovirus D68, West Nile Virus)

- Botulism

- Tick Paralysis

- Traumatic neuritis

- Toxic neuropathies

Excluding these conditions is a crucial part of the diagnostic process for suspected polio, especially in polio-free regions.

Outline the Management of Acute Polio Infection

Unfortunately, there is no specific antiviral drug or cure for poliovirus infection. Once paralysis sets in, the damage to motor neurons is largely irreversible. Therefore, management of acute polio infection is entirely supportive, aimed at alleviating symptoms, preventing complications, and maximizing functional recovery.

A. No Specific Antiviral Treatment:

- Unlike some viral infections where antiviral medications can inhibit viral replication, there are no effective antiviral drugs against poliovirus currently available. Antibiotics are also ineffective as polio is a viral disease.

- The focus is entirely on supportive care.

B. Supportive Care Strategies:

- Rest and Observation:

- Patients require bed rest, especially during the acute phase.

- Close monitoring for progression of paralysis, especially respiratory muscle involvement, is critical.

- Pain Management:

- Acute polio often causes severe muscle pain, spasms, and tenderness.

- Analgesics: Pain relievers (e.g., NSAIDs, opioids in severe cases) are used to manage pain.

- Muscle Relaxants: May be used to alleviate muscle spasms.

- Warm Compresses/Heat Therapy: Can provide comfort and reduce muscle stiffness.

- Respiratory Support:

- This is the most critical aspect of care, particularly in bulbar and bulbospinal polio, or severe spinal polio affecting the diaphragm and intercostal muscles.

- Monitoring: Continuous monitoring of respiratory function (e.g., respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, vital capacity) is essential.

- Mechanical Ventilation: Patients with respiratory paralysis require immediate and continuous mechanical ventilation. Historically, this involved negative pressure ventilators like the "iron lung"; today, positive pressure ventilators are used.

- Tracheostomy: May be necessary for prolonged ventilation or to manage airway secretions.

- Airway Management: Careful attention to maintaining a clear airway, especially in bulbar polio where swallowing difficulties (dysphagia) increase the risk of aspiration. Suctioning of secretions is often needed.

- Nutritional Support and Hydration:

- Maintaining adequate hydration and nutrition is important, especially in patients with fever, vomiting, or dysphagia.

- Intravenous Fluids: May be necessary.

- Nasogastric or Gastrostomy Tube Feeding: For patients with severe dysphagia to prevent aspiration and ensure adequate caloric intake.

- Bladder and Bowel Management:

- Poliovirus can occasionally affect bladder and bowel function, leading to urinary retention or constipation.

- Catheterization: May be required for urinary retention.

- Laxatives/Stool Softeners: To manage constipation.

- Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation (Early and Ongoing):

- Prevention of Deformities: This is paramount to minimize long-term disability.

- Positioning: Proper positioning of limbs in functional alignment to prevent contractures and pressure sores.

- Passive Range of Motion Exercises: Gentle exercises performed by a therapist or caregiver to maintain joint flexibility and prevent stiffness in paralyzed limbs. These should be started early, even during the acute painful phase, to the patient's tolerance.

- Splinting/Bracing: To support weak limbs, prevent overstretching of muscles, and maintain proper joint alignment.

- Muscle Strengthening (Post-Acute Phase): Once the acute phase resolves and pain subsides, active physical therapy is initiated to strengthen remaining muscle function, improve motor control, and teach compensatory strategies.

- Occupational Therapy: To help patients adapt to daily living activities with their residual disabilities.

- Assistive Devices: Prescription of braces, crutches, wheelchairs, or other aids to facilitate mobility and independence.

- Psychological Support: Dealing with permanent paralysis and disability can be emotionally devastating. Psychological support for both the patient and their family is crucial.

- Prevention of Deformities: This is paramount to minimize long-term disability.

Discussion of Post-Polio Syndrome (PPS)

Even individuals who recovered significantly from paralytic polio decades ago can experience a late-onset complication known as Post-Polio Syndrome (PPS). This condition highlights the long-term impact of poliovirus infection on the nervous system.

A. Definition and Onset:

- Late-Onset Complication: PPS is a condition that affects polio survivors, typically occurring 15 to 40 years or more after the initial paralytic poliovirus infection. It is not a recurrence of the original poliovirus infection (the virus is no longer present in the body).

- Progressive Nature: PPS is characterized by a gradual and progressive weakening of muscles that were previously affected by polio and/or muscles that seemingly recovered fully or were unaffected by the initial infection.

B. Characteristic Symptoms:

The most common symptoms of PPS include:

- New Muscle Weakness: This is the hallmark symptom. It can manifest as new weakness in muscles previously affected and/or in muscles that were thought to be spared or had recovered. This weakness is often asymmetric and slowly progressive.

- Overwhelming Fatigue: Profound, often debilitating, fatigue that is not relieved by rest. This fatigue can be physical, mental, or both.

- Muscle and Joint Pain: Chronic pain, often described as aching, burning, or cramping, in muscles and joints. This pain can be exacerbated by activity or changes in weather.

- Muscle Atrophy: Wasting away of muscle tissue in affected areas.

- New or Worsening Atrophy: Individuals may notice a reduction in muscle bulk in previously affected or seemingly unaffected limbs.

- Functional Decline: Difficulty with activities of daily living that were previously manageable (e.g., walking, climbing stairs, lifting objects).

- Cold Intolerance: Increased sensitivity to cold temperatures.

- Sleep Disorders: Including sleep apnea.

- Swallowing or Breathing Difficulties: In severe cases, especially if the original polio was bulbar, new or worsening dysphagia or respiratory insufficiency can occur.

C. Hypothesized Pathophysiology:

The exact mechanism of PPS is not fully understood, but the leading hypothesis centers on the degeneration of overused motor units in the aging nervous system.

- Initial Polio Damage: The original poliovirus infection destroyed a significant number of motor neurons in the spinal cord and brainstem.

- Compensatory Mechanism (Motor Unit Enlargement): To compensate for the lost neurons, surviving motor neurons "sprouted" new nerve endings. These new nerve endings re-innervated muscle fibers that had been orphaned by the death of their original motor neurons. This process created enlarged motor units—a single surviving motor neuron now controls a much larger number of muscle fibers than it normally would. This allows for significant functional recovery after acute polio.

- Metabolic Overload and Degeneration: These enlarged motor units have to work much harder and are under increased metabolic stress. Over decades, this chronic overuse and metabolic demand eventually lead to:

- Premature degeneration of the nerve sprouts from the enlarged motor units.

- Eventual death of the compensating motor neurons themselves.

- Progressive Weakness: As these enlarged motor units degenerate, muscle fibers once again become denervated, leading to new or worsening muscle weakness, fatigue, and atrophy.

- Aging Factor: The normal aging process, which also involves a gradual loss of motor neurons, likely contributes to the onset and progression of PPS.

D. Diagnosis and Management:

- Diagnosis: PPS is a diagnosis of exclusion, based on the presence of the characteristic symptoms in an individual with a confirmed history of paralytic polio, after ruling out other medical conditions. There is no specific diagnostic test.

- Management: Management is symptomatic and supportive:

- Energy Conservation: Pacing activities, avoiding overuse, and adequate rest are crucial to manage fatigue and prevent further muscle damage.

- Physical Therapy: Gentle, non-fatiguing exercises to maintain strength and flexibility, and the use of assistive devices (braces, walkers) to reduce strain on weakened muscles.

- Pain Management: Medications and non-pharmacological approaches to address muscle and joint pain.

- Lifestyle Modifications: Weight management, ergonomic adjustments, and assistive technology.

Understanding PPS underscores the long-term public health burden of polio, even for those who survived the acute infection.

Prevention of Polio: The Role of Vaccination

Vaccination is the single most effective tool for preventing poliovirus infection and is the cornerstone of global polio eradication efforts. Without widespread vaccination, polio would undoubtedly resurge.

A. Importance of Vaccination:

- Only Effective Prevention: As there is no cure for polio, prevention through vaccination is the only way to protect individuals and achieve global eradication.

- Herd Immunity: High vaccination coverage within a population creates "herd immunity," protecting even unvaccinated individuals by making it difficult for the virus to spread.

- Global Eradication: The GPEI relies entirely on achieving and maintaining high vaccination rates worldwide to interrupt poliovirus transmission permanently.

B. Types of Polio Vaccines:

- Inactivated Poliovirus Vaccine (IPV) - Salk Vaccine:

- Composition: Contains inactivated (killed) poliovirus of all three serotypes (Type 1, 2, and 3).

- Administration: Given by injection (intramuscular or subcutaneous).

- Advantages:

- Safety: Cannot cause vaccine-associated paralytic polio (VAPP) because it contains only killed virus.

- Systemic Immunity: Elicits a strong systemic antibody response, providing excellent individual protection against paralytic disease.

- Disadvantages:

- Limited Intestinal Immunity: Induces very little intestinal immunity. This means that while vaccinated individuals are protected from paralysis, they can still be infected with wild poliovirus and shed it in their feces, potentially transmitting it to unvaccinated individuals. This is a critical limitation for eradication.

- Cost and Administration: More expensive per dose and requires trained health workers for administration (injection).

- No Herd Immunity via shedding: Does not contribute to herd immunity by preventing intestinal infection and transmission as effectively as OPV.

- Current Use: IPV is now used in almost all polio-free countries and is being increasingly incorporated into immunization schedules in countries transitioning away from OPV. The current global strategy emphasizes the use of at least one dose of IPV.

- Oral Poliovirus Vaccine (OPV) - Sabin Vaccine:

- Composition: Contains live, attenuated (weakened) poliovirus of one, two, or all three serotypes.

- Trivalent OPV (tOPV): Contained Type 1, 2, and 3 (no longer in use globally).

- Bivalent OPV (bOPV): Contains Type 1 and 3 (currently in use globally after the Type 2 switch).

- Monovalent OPV (mOPV): Contains only one serotype (used for outbreak response).

- Administration: Given orally (drops into the mouth).

- Advantages:

- Easy Administration: Simple to administer, does not require trained personnel, making it ideal for mass vaccination campaigns, especially in remote areas.

- Intestinal Immunity (Mucosal Immunity): Induces excellent intestinal (mucosal) immunity, which is crucial for blocking both infection and transmission of wild polioviovirus. This is its key advantage for eradication.

- Herd Immunity via shedding: Vaccinated individuals can shed the attenuated vaccine virus in their feces, which can then circulate in communities (especially in areas with poor sanitation). This can indirectly immunize some unvaccinated contacts, contributing to herd immunity.

- Cost: Generally less expensive per dose than IPV.

- Disadvantages:

- Risk of Vaccine-Associated Paralytic Polio (VAPP): In very rare cases (about 1 in 2.7 million first doses), the live attenuated virus in OPV can revert to a neurovirulent form and cause paralysis in the vaccinated individual or a close contact. This risk is primarily associated with the Type 2 component.

- Circulating Vaccine-Derived Poliovirus (cVDPV): In areas with very low vaccination coverage and poor sanitation, the attenuated vaccine virus can circulate for a long time, undergoing genetic mutations that cause it to regain neurovirulence, leading to outbreaks of cVDPV. This is a significant challenge to eradication, especially for Type 2 (cVDPV2).

- Current Use: OPV has been the primary tool for eradication campaigns due to its ability to block transmission. However, its use is being phased out or carefully managed to eliminate VAPP and cVDPV risks as wild poliovirus nears eradication.

- Composition: Contains live, attenuated (weakened) poliovirus of one, two, or all three serotypes.

C. Global Polio Eradication Strategy (GPEI):

The GPEI, led by WHO, UNICEF, Rotary International, CDC, and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, employs a comprehensive strategy:

- High Vaccination Coverage: Achieving and maintaining extremely high coverage with both OPV and IPV.

- Switch from tOPV to bOPV: To eliminate the risk of Type 2 VAPP/cVDPV after WPV2 eradication.

- Outbreak Response: Rapid and targeted vaccination campaigns using monovalent OPV (mOPV) or bOPV in response to any detected poliovirus (WPV or cVDPV) to contain outbreaks.

- Surveillance: Robust surveillance systems, including AFP surveillance and environmental surveillance (wastewater testing), to detect all poliovirus cases and circulation.

- Containment: Rigorous biosafety measures in laboratories to contain all remaining poliovirus samples.

- Transition to IPV: Gradually transitioning all countries to an all-IPV schedule once wild poliovirus is fully eradicated, to completely eliminate the risks associated with OPV.