Tendonitis (or Tendinitis) is the inflammation or irritation of a tendon. It is a condition characterized by pain, swelling, and impaired function of a tendon.

While tendonitis can occur in any of the body’s tendons, it is most frequently observed in areas subject to repetitive motion and stress. These commonly affected areas include:

- Shoulders (e.g., rotator cuff tendons)

- Elbows (e.g., lateral and medial epicondyle tendons)

- Wrists

- Knees (e.g., patellar tendon)

- Heels (e.g., Achilles tendon)

- Definition: A tendon is a robust, fibrous connective tissue made primarily of collagen fibers. Its fundamental role is to mechanically connect muscle to bone.

- Composition: Primarily composed of parallel bundles of collagen fibers (mainly Type I collagen), providing its characteristic tensile strength. These collagen fibers are organized in a hierarchical manner, contributing to the tendon's ability to withstand significant loads.

- Tendon Sheath: Some tendons, particularly those that pass around bony prominences or through constricted spaces (e.g., in the wrist and ankle), are surrounded by a tendon sheath.

- Description: This is a membrane-like structure, often filled with synovial fluid, that encases the tendon.

- Function: It acts to reduce friction between the tendon and surrounding tissues (like bone or other tendons), allowing the tendon to glide smoothly and efficiently during movement.

- Primary Cell Types: Tendons have a relatively low cellularity, with specialized cells crucial for maintaining and repairing the tendon matrix.

- Tenocytes (Fibrocytes): These are the mature, spindle-shaped cells that are the main cellular component within the tendon. They are embedded within the collagen matrix, typically anchored to the collagen fibers. Their primary role is to maintain the tendon's extracellular matrix (ECM) by continuously synthesizing and degrading collagen and other matrix components.

- Tenoblasts (Fibroblasts): These are the immature, more metabolically active precursors to tenocytes. They are also spindle-shaped and are primarily involved in the synthesis of new collagen and other components of the ECM, particularly during growth, development, or repair processes. They are highly proliferative and can be found in clusters, often free from collagen fibers.

- Movement Transmission: The most critical function is to transmit the force generated by muscular contraction to the skeletal levers (bones). This direct transmission of force is what allows for a wide range of body movements, from fine motor skills to gross locomotion.

- Body Posture Maintenance: By transmitting muscle tension, tendons also play a vital role in maintaining body posture against gravity.

- Muscle Injury Prevention: Tendons act as elastic buffers. They absorb some of the impact and shock that muscles would otherwise experience during dynamic activities like running, jumping, or sudden changes in direction. This shock absorption helps to protect the muscle fibers from excessive strain and potential injury.

- Stiffness & Tensile Strength: Tendons are inherently stiffer and possess greater tensile strength compared to muscles. This allows them to withstand very large loads with minimal deformation, effectively transferring force without significant energy loss.

- Difference from Ligaments: It's crucial to differentiate tendons from ligaments.

- Tendons: Connect muscle to bone.

- Ligaments: Connect bone to other bones, primarily providing stability to joints.

- Difference from Tendinosis: While often confused, tendonitis implies inflammation, whereas tendinosis is a chronic condition involving degeneration of the tendon collagen at a cellular level, often without significant inflammatory cells. Tendinosis is characterized by the breakdown and disorganization of the tendon structure over time.

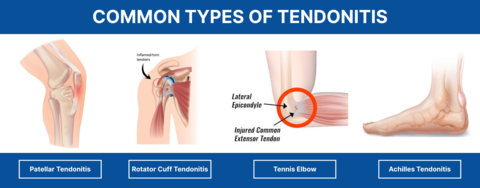

Tendonitis can manifest in various locations throughout the body, often named for the specific tendon affected or the activity that commonly leads to its development. Here are some of the most common types:

- Achilles Tendonitis:

- Description: Inflammation of the Achilles tendon, which connects the calf muscles to the heel bone.

- Commonality: A very common sports injury, especially in activities involving running and jumping.

- Associations: Individuals with systemic inflammatory conditions like rheumatoid arthritis are also at a higher risk.

- Tennis Elbow (Lateral Epicondylitis):

- Description: A painful condition affecting the tendons on the outside (lateral aspect) of the elbow. These tendons are involved in extending the wrist and fingers.

- Cause: Typically occurs when these elbow tendons are overloaded, often by repetitive motions of the arm and wrist, such as those involved in gripping and backhand strokes in tennis.

- Wrist Tendonitis (General): Can affect anyone who repeatedly performs the same movements with their wrists. It is common in individuals who engage in extensive typing, writing, or sports like tennis.

- Golfer’s Elbow (Medial Epicondylitis):

- Description: Characterized by pain originating from the elbow and extending to the wrist on the inside (medial side) of the elbow. This involves the tendons that flex the wrist and fingers.

- Alternative Names: Also known as baseball elbow, suitcase elbow, or forehand tennis elbow due to the activities commonly associated with its development.

- Pitcher’s Shoulder:

- Description: A general term for inflammation or irritation in the shoulder tendons, often related to the rotator cuff.

- Cause: Occurs when the shoulder muscles and tendons, particularly those of the rotator cuff, are overworked. It is frequently seen in athletes involved in overhead throwing motions.

- Swimmer’s Shoulder (Shoulder Impingement):

- Description: A condition where the rotator cuff tendons (and sometimes the bursa) get pinched or "impinged" in the subacromial space.

- Cause: Swimmers frequently aggravate their shoulders due to the constant, repetitive rotation and overhead movements involved in swimming strokes.

- Supraspinatus Tendonitis: A specific form of swimmer's shoulder where the supraspinatus tendon (one of the rotator cuff tendons, located at the top of the shoulder joint) becomes inflamed, causing pain when moving the arm, especially overhead.

- Jumper’s Knee (Patellar Tendonitis):

- Description: Inflammation of the patellar tendon, which connects the kneecap (patella) to the shin bone (tibia).

- Cause: Commonly seen in athletes whose sports involve repetitive jumping, leading to stress and microtrauma to the patellar tendon.

Tendonitis typically doesn't arise from a single event but rather from a combination of factors that stress the tendon beyond its capacity to adapt.

- Repetitive Motion / Overuse: This is the most common cause. Tendonitis is much more likely to stem from the repetition of a particular movement over time rather than a sudden, acute injury. Performing the same motion repeatedly can lead to microscopic tears in the tendon, and if adequate rest and recovery are not allowed, these microtraumas accumulate, leading to inflammation and degeneration.

- Strain: Stretching or tearing of a muscle or the tissue connecting muscle to bone (tendon) beyond its physiological limits.

- Excessive Exercises: Engaging in workouts that are too intense, too frequent, or involve improper form can overload tendons.

- Injury or Trauma: While less common as the sole cause, a direct blow or acute injury can sometimes initiate tendon inflammation.

- Improper Technique: Incorrect biomechanics during sports, work, or daily activities can place undue stress on specific tendons.

- Poor Ergonomics: An improperly set up workstation, for example, can contribute to wrist or elbow tendonitis.

- Unaccustomed Activity: Suddenly increasing the intensity, duration, or type of physical activity without gradual conditioning can overwhelm tendons.

These are factors that increase an individual's susceptibility to developing tendonitis.

- Age:

- As people age, tendons naturally become less flexible, less elastic, and less tolerant to stress.

- Blood supply to tendons also tends to decrease with age, impairing their ability to repair themselves effectively.

- This makes elderly individuals more prone to tendon injuries and slower to recover.

- Sports and Exercises: Participation in sports or activities that involve repetitive motions or high impact can significantly increase the risk. Examples include tennis, golf, swimming, running, basketball, and throwing sports.

- Occupational Activities: Jobs requiring repetitive tasks, forceful exertions, awkward postures, or vibrating equipment can also contribute to tendonitis (e.g., assembly line workers, musicians, data entry professionals).

- Medical Conditions:

- Diabetes: Individuals with diabetes often have impaired circulation and collagen abnormalities, which can make tendons more susceptible to injury and hinder healing.

- Rheumatoid Arthritis: This autoimmune disease causes chronic inflammation throughout the body, including joints and surrounding tissues, which can directly affect tendons and increase the risk of tendonitis and even rupture.

- Other inflammatory conditions: Gout, psoriatic arthritis, and thyroid disorders can also be associated with tendon problems.

- Medications:

- Fluoroquinolone Antibiotics: Drugs like ciprofloxacin (Cipro) and levofloxacin have a known side effect of increasing the risk of tendon inflammation and rupture, particularly the Achilles tendon.

- Biomechanical Imbalances: Issues such as flat feet, leg length discrepancies, muscle weakness, or tightness can alter body mechanics and place excessive stress on certain tendons.

- Obesity: Increased body weight can place additional stress on weight-bearing tendons.

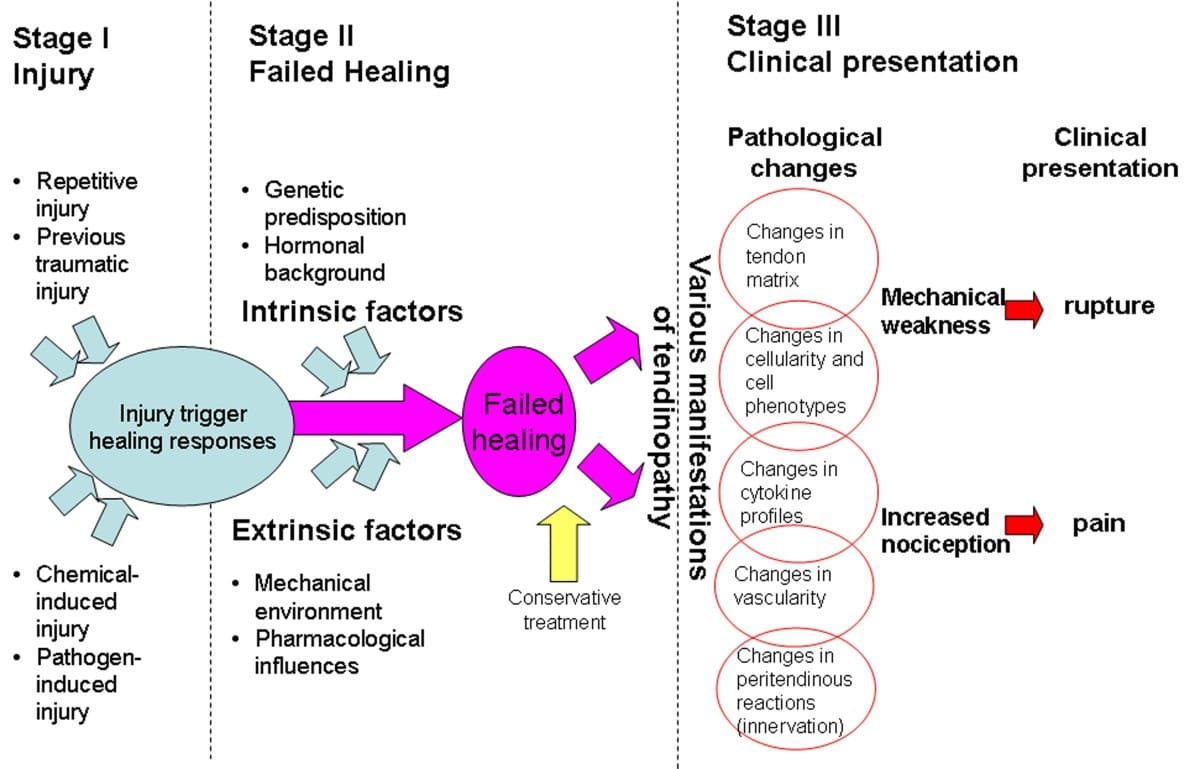

The pathophysiology of tendonitis describes the cellular and structural changes that occur within a tendon leading to the symptoms of inflammation and pain. While historically viewed as purely inflammatory, it's now understood that a spectrum of conditions exists, from acute inflammation to chronic degeneration (tendinosis). However, for true "tendonitis," the inflammatory component is key.

- Initial Irritation and Microtrauma:

- The primary cause of tendonitis is typically irritation or overload of the tendon, often due to prolonged or abnormal use (as discussed in Objective 4). This repetitive stress or unaccustomed strain leads to microscopic tears and damage within the collagen fibers and other components of the tendon.

- Inflammatory Response:

- In response to this microtrauma and irritation, the body initiates an inflammatory cascade. This is the body's natural healing mechanism designed to remove damaged tissue and initiate repair.

- Cellular Infiltration: Inflammatory cells (e.g., macrophages, neutrophils) migrate to the site of injury.

- Chemical Mediators: These cells release various chemical mediators (e.g., prostaglandins, cytokines, histamine) that contribute to the hallmarks of inflammation.

- Effects of Inflammation:

- Increased Vascular Permeability: Chemical mediators cause blood vessels in the area to become more permeable, allowing fluid and proteins to leak out into the surrounding tissue.

- Swelling (Edema): The leakage of fluid results in localized swelling.

- Redness (Erythema): Increased blood flow to the area causes redness.

- Heat (Calor): Increased metabolic activity and blood flow contribute to localized warmth.

- Pain (Dolor): Swelling puts pressure on nerve endings, and chemical mediators directly stimulate pain receptors, leading to the characteristic pain of tendonitis.

- Involvement of Tendon Sheaths:

- If the affected tendon is surrounded by a tendon sheath, the inflammation can involve this structure (a condition sometimes specifically called tenosynovitis).

- Mechanism: Inflammation in the sheath of the tendon produces swelling, redness, and pain along the course of the involved tendon.

- Functional Impairment: Swelling of the sheath narrows the space through which the tendon normally glides, causing stiffness in the involved area and making movement painful.

- Crepitus: The inflamed and often roughened surfaces of the tendon and its sheath can rub against each other, producing a palpable or audible grating sensation (crepitus) when the tendon moves.

- Bacterial Infection (Less Common):

- Less frequently, tendonitis can arise from an invasion of the tendon sheaths by bacteria, leading to a direct infection. This is a more serious condition and requires specific antibiotic treatment.

- Progression to Chronic Conditions (Tendinosis):

- If the irritating factors persist and the tendon is not allowed to heal, the acute inflammatory phase may transition into a chronic degenerative process known as tendinosis. In tendinosis, the primary features are collagen disorganization, increased cellularity, and neovascularization (new blood vessel growth), often with a lack of prominent inflammatory cells. While "tendonitis" strictly implies inflammation, the term is often used clinically to encompass both acute inflammatory states and chronic degenerative issues.

Tendonitis presents with a characteristic set of signs (observable by others) and symptoms (experienced by the patient) that indicate inflammation and irritation of the tendon. These generally reflect the underlying inflammatory processes and mechanical stress.

- Pain:

- Description: Often described as a dull ache that is localized to the affected area.

- Characteristics: The pain typically worsens with movement or activity of the affected limb or joint. It tends to increase significantly when the injured area is used, especially against resistance.

- Progression: May be mild at rest but becomes sharp and severe with specific movements.

- Description: The affected area will be tender to the touch (palpation).

- Characteristics: Increased pain will be felt if someone presses directly on the inflamed tendon. This pinpoint tenderness is a key diagnostic clue.

- Description: Visible or palpable swelling around the affected tendon.

- Characteristics: This is due to the accumulation of inflammatory fluid within the tendon itself or its surrounding sheath. The swelling might make the area feel fuller or appear slightly larger than the unaffected side.

- Description: The skin overlying the inflamed tendon may appear visibly red and feel warm to the touch.

- Characteristics: These are classic signs of inflammation, resulting from increased blood flow to the injured area as part of the body's healing response.

- Description: Patients may report feeling or hearing a creaking, grating, or crackling sensation when they move the affected tendon or joint.

- Characteristics: This sensation occurs when the inflamed or roughened tendon slides within its sheath or over bony prominences, indicating friction due to the inflammatory process.

- Description: A feeling of stiffness or reduced flexibility in the affected area, making it difficult or painful to move the limb through its full range of motion.

- Characteristics: This is often more noticeable after periods of rest (e.g., in the morning) and may improve slightly with gentle movement, though overuse will exacerbate the pain.

- Description: Weakness in the affected limb or muscle group, particularly when performing actions that engage the injured tendon.

- Characteristics: This weakness can be due to pain inhibiting muscle contraction, or due to impaired function of the tendon itself.

Diagnosing tendonitis typically involves a combination of patient history, physical examination, and, in some cases, imaging studies to confirm the diagnosis, assess the extent of the injury, and rule out other conditions.

- History Taking: The healthcare provider will begin by asking about the patient's symptoms, including when the pain started, its location, intensity, what activities worsen or alleviate it, and any history of repetitive activities, sports, or trauma. Information on past medical history (e.g., diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis) and current medications is also crucial.

- Inspection: The affected area will be visually inspected for signs of inflammation such as redness, swelling, or deformities.

- Palpation: The clinician will gently feel the area to pinpoint tenderness directly over the tendon, assess for swelling, warmth, or the presence of crepitus (grating sensation) during movement.

- Range of Motion (ROM) Assessment: The patient's active and passive range of motion in the affected joint will be evaluated to identify limitations, pain with movement, and specific positions that exacerbate symptoms.

- Strength Testing: Muscle strength related to the affected tendon will be assessed, often revealing pain or weakness when resisting movement that engages the tendon. Specific orthopedic tests (e.g., Finkelstein's test for De Quervain's tenosynovitis, or various shoulder impingement tests) may be performed depending on the suspected location.

These are often used to confirm the diagnosis, assess the severity of tendon damage (e.g., tears, degeneration), and differentiate tendonitis from other conditions.

- Ultrasound:

- Description: A non-invasive imaging technique that uses sound waves to create real-time images of soft tissues.

- Utility: Excellent for visualizing tendons, showing signs of inflammation (e.g., tendon thickening, fluid in the tendon sheath), structural changes (e.g., loss of normal fibrillar pattern, hypoechoic areas), and can detect small tears or ruptures. It's particularly useful for dynamic assessment (observing the tendon during movement).

- MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) Scans:

- Description: A non-invasive imaging technique that uses strong magnetic fields and radio waves to create detailed images of organs and soft tissues.

- Utility: Provides high-resolution images of tendons, muscles, ligaments, and surrounding structures. It is highly effective in determining:

- Tendon thickening or swelling.

- Fluid accumulation within the tendon sheath.

- Areas of degeneration (tendinosis).

- Partial or complete tendon tears/ruptures.

- Dislocations of tendons.

- Inflammation in surrounding tissues.

- Can help rule out other pathologies like bone marrow edema or stress fractures.

- X-ray:

- Description: Uses electromagnetic radiation to produce images of bones.

- Utility: While X-rays do not directly visualize soft tissues like tendons, they are important for:

- Ruling out other conditions: Such as fractures, dislocations, or arthritis, which can present with similar pain.

- Identifying calcifications: In some chronic cases of tendonitis (e.g., calcific tendonitis in the shoulder), calcium deposits within the tendon can be visible on X-ray.

- Typically not used to diagnose tendonitis directly, but may be ordered if an underlying systemic condition (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis, gout, infection) is suspected as a contributing factor. For example, inflammatory markers (ESR, CRP) or autoimmune antibodies might be checked.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/2548611-article-wrist-tendonitis-5a71f4a0d8fdd5003613b12c.png)

The primary goals of managing tendonitis are to reduce pain and inflammation, promote healing, and restore function. Treatment often begins with conservative measures, focusing on reducing stress on the affected tendon.

- Description: This is fundamental. It involves reducing or completely avoiding activities that aggravate the tendon.

- Rationale: Allows the inflamed tendon to heal without continued stress, preventing further microtrauma. Complete immobilization is rarely necessary; often, simply modifying activities or using an assistive device (like crutches for Achilles tendonitis) is sufficient.

- Goal: To allow the inflammatory process to subside and the tendon to begin repairing itself.

- Description: Applying cold packs or ice to the affected area for 15-20 minutes, several times a day.

- Rationale: Cold therapy helps to constrict blood vessels, thereby reducing blood flow to the area. This effectively decreases swelling, pain, and local inflammation.

- Application: Always use a barrier (towel) between the ice pack and skin to prevent frostbite.

- Description: Applying a compression bandage (e.g., elastic wrap, sleeve) to the affected area.

- Rationale: Helps to limit swelling and provide mild support to the injured area.

- Application: Ensure the bandage is snug but not so tight that it restricts circulation.

- Description: Raising the injured limb above the level of the heart.

- Rationale: Uses gravity to help drain excess fluid away from the injured area, thereby reducing swelling.

- Application: Most effective when combined with rest and ice.

- Acetaminophen (Tylenol): Can be used for pain relief, but does not have significant anti-inflammatory effects.

- Description: Over-the-counter (OTC) options include ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin) and naproxen (Aleve). Prescription-strength NSAIDs may also be prescribed.

- Rationale: NSAIDs reduce pain and inflammation by inhibiting the production of prostaglandins, which are key mediators of the inflammatory response.

- Application: Can be taken orally or applied topically (e.g., diclofenac gel) to the affected area, which may reduce systemic side effects.

- Caution: Long-term use of oral NSAIDs can have side effects on the gastrointestinal tract (ulcers, bleeding), kidneys, and cardiovascular system.

- Description: An injection of a corticosteroid (a potent anti-inflammatory medication) directly into the area around the tendon (but not directly into the tendon itself, as this can weaken it and increase the risk of rupture). Often mixed with a local anesthetic.

- Rationale: Provides rapid and significant reduction in local inflammation and pain.

- Application: Used for acute, severe pain, or when other conservative measures have failed.

- Caution: Corticosteroid injections provide temporary relief and do not address the underlying cause. Repeated injections are generally discouraged due to potential side effects like tendon weakening, atrophy of surrounding tissues, and increased risk of rupture.

- Description: A crucial component of long-term management. Involves a structured program of exercises and modalities.

- Goals:

- Stretching: To improve flexibility and range of motion in the affected joint and surrounding muscles.

- Strengthening: To build strength in the muscles that support the tendon, improving stability and reducing future strain.

- Eccentric Exercises: Often specifically prescribed for tendinopathies (e.g., for Achilles or patellar tendonitis), as they have shown benefit in remodeling the tendon.

- Ergonomic Assessment: Identifying and correcting poor posture, body mechanics, or workstation setup to prevent recurrence.

- Modalities: May include therapeutic ultrasound, electrical stimulation, or heat/cold therapy to aid in pain relief and healing.

- Description: Splints, braces, slings, or walking boots.

- Rationale: To immobilize or provide support to the affected joint, reducing stress on the tendon and promoting healing.

- Application: Used temporarily during the acute phase or during activities that might exacerbate the condition.

Surgical intervention for tendonitis is generally considered a last resort, reserved for chronic, severe cases that have not responded to extensive conservative management (including physical therapy, medications, and injections) over a period of several months (typically 6-12 months). The goal of surgery is to remove damaged tissue, repair the tendon, and alleviate chronic pain and functional impairment.

- Persistent, debilitating pain despite non-surgical treatments.

- Significant functional impairment due to pain or weakness.

- Evidence of severe degenerative changes or partial tears on imaging (MRI or ultrasound).

- Tendon rupture (which often requires immediate surgical repair).

The specific procedure depends on the affected tendon, the extent of damage, and the surgeon's preference.

- Debridement:

- Description: This involves removing the damaged, degenerated, or inflamed tissue from around and within the tendon. This can include:

- Synovectomy: Removal of inflamed tendon sheath lining.

- Excision of Degenerated Tissue: Trimming away unhealthy, scarred, or calcified portions of the tendon.

- Rationale: To remove the source of chronic inflammation and pain, and to promote a healthier healing environment.

- Approach: Can be done through an open incision or arthroscopically (minimally invasive, using small incisions and a camera).

- Description: This involves removing the damaged, degenerated, or inflamed tissue from around and within the tendon. This can include:

- Tendon Repair:

- Description: If there is a partial tear or significant degeneration, the surgeon may debride the damaged area and then repair the remaining healthy tendon tissue. This might involve:

- Suturing: Stitching together torn tendon fibers.

- Augmentation: In some cases, a graft (from another part of the patient's body or a donor) or synthetic material may be used to reinforce a severely weakened or partially torn tendon.

- Rationale: To restore the structural integrity and strength of the tendon.

- Description: If there is a partial tear or significant degeneration, the surgeon may debride the damaged area and then repair the remaining healthy tendon tissue. This might involve:

- Tenotomy:

- Description: A surgical incision into a tendon. In some specific cases, a partial release or lengthening of a tight tendon may be performed.

- Rationale: To relieve tension and improve function. For example, in chronic Achilles tendinopathy, a partial tenotomy might be considered.

- Release Procedures (e.g., for Tenosynovitis):

- Description: If the tendon is constricted within its sheath (e.g., in De Quervain's tenosynovitis or trigger finger), the surgeon may make an incision in the tendon sheath to widen the space and allow the tendon to glide freely.

- Rationale: To relieve mechanical impingement and reduce pain.

- Reattachment/Transfer Procedures:

- Description: In cases of complete tendon rupture (e.g., rotator cuff tear, Achilles tendon rupture), the torn ends of the tendon are surgically reattached to the bone. If the original tendon is severely damaged or insufficient, a tendon transfer (using a healthy tendon from a nearby muscle to take over the function of the damaged one) might be necessary.

- Rationale: To restore the complete function of the muscle-tendon unit.

- Surgery is almost always followed by a rigorous and prolonged period of physical therapy. This is crucial for successful outcomes and involves:

- Initial immobilization (splint, cast, brace) to protect the repair.

- Gradual reintroduction of range-of-motion exercises.

- Progressive strengthening exercises.

- Functional training to restore full activity.

- Rehabilitation can take several weeks to many months, depending on the procedure and individual healing.

- As with any surgical procedure, risks include infection, bleeding, nerve damage, anesthesia complications, scar tissue formation, persistent pain, and the possibility of re-rupture or failure of the repair.

Preventing tendonitis largely involves addressing the primary causes and risk factors, particularly overuse, improper technique, and biomechanical imbalances. A proactive approach can significantly reduce the likelihood of developing this painful condition.

- Principle: Avoid sudden increases in the intensity, duration, or frequency of physical activity, whether in sports, exercise, or work tasks.

- Application: Gradually increase demands on tendons over time. For athletes, this means a structured training program that slowly builds up mileage, weight, or repetitions. For occupational tasks, it means taking breaks and not overexerting too quickly.

- Principle: Incorrect movement patterns place undue stress on specific tendons.

- Application:

- Sports: Seek coaching or instruction to learn and maintain correct form in activities like tennis, golf, swimming, running, or lifting weights.

- Work/Daily Activities: Be mindful of posture and how you perform repetitive tasks.

- Principle: Prepare muscles and tendons for activity and help them recover afterward.

- Application:

- Warm-up: Before any physical activity, perform light aerobic exercise (e.g., walking, cycling) for 5-10 minutes to increase blood flow to muscles and tendons, followed by dynamic stretches that mimic the movements of the activity.

- Cool-down: After activity, perform gentle static stretches to improve flexibility and aid in recovery. Hold stretches for 20-30 seconds.

- Principle: Flexible muscles and tendons are less prone to injury.

- Application: Incorporate regular stretching into your routine, focusing on muscle groups that cross the joints prone to tendonitis. This helps maintain a good range of motion and reduces tension on tendons.

- Principle: Strong muscles provide better support and shock absorption for tendons.

- Application: Include exercises that strengthen the muscles surrounding the tendons, as well as core muscles, to improve overall stability and reduce strain. Pay attention to balanced strength between opposing muscle groups.

- Principle: Optimize your work or living environment to minimize awkward postures and repetitive strain.

- Application:

- Workstation: Adjust chair, desk, keyboard, and monitor height to maintain neutral joint positions.

- Tools: Use ergonomic tools or modify how you hold them to reduce stress on hands, wrists, and elbows.

- Breaks: Take frequent short breaks to stretch and move, especially during repetitive tasks.

- Principle: Using the right gear can absorb shock and provide support.

- Application:

- Footwear: Wear supportive shoes appropriate for your activity, replacing them when worn out. Consider orthotics if you have biomechanical issues (e.g., flat feet).

- Sports Equipment: Ensure racquets, clubs, or other equipment are properly sized and weighted.

- Principle: Early recognition of pain or discomfort is crucial to prevent progression to chronic tendonitis.

- Application: Do not "play through" pain. If you experience initial discomfort, reduce activity, apply R.I.C.E., and give your body time to recover. Adequate sleep is also essential for tissue repair.

- Principle: Systemic health influences tendon health.

- Application:

- Nutrition: A balanced diet rich in vitamins and minerals supports tissue health and repair.

- Hydration: Stay well-hydrated.

- Weight Management: Maintain a healthy weight to reduce stress on weight-bearing tendons.

- Manage Chronic Conditions: Effectively manage conditions like diabetes or rheumatoid arthritis, as they can predispose individuals to tendon issues.

- Related to: Inflammation and irritation of the tendon, muscle spasm, pressure on nerve endings.

- As evidenced by: Patient's verbal reports of pain (e.g., "aching," "sharp," "dull"), grimacing, guarding behavior, restlessness, changes in vital signs (e.g., increased heart rate, blood pressure) in acute phase, limited range of motion, reluctance to move affected part, tenderness to palpation.

- Related to: Pain, swelling, decreased muscle strength, stiffness, fear of movement (kinesiophobia), therapeutic restrictions (e.g., splint, brace).

- As evidenced by: Reluctance to move affected joint/limb, decreased range of motion, difficulty performing activities of daily living (ADLs), gait changes (if lower extremity affected), decreased muscle strength, use of assistive devices.

- Related to: Pain, weakness, deconditioning, fear of re-injury.

- As evidenced by: Verbal reports of fatigue or weakness, dyspnea on exertion, inability to perform usual activities, discomfort during activity, changes in vital signs during activity, withdrawal from social activities.

- Related to: Lack of exposure to information, misinterpretation of information, unfamiliarity with information resources regarding the condition, treatment, and self-care.

- As evidenced by: Verbalization of questions, inaccurate follow-through of instructions, inappropriate or exaggerated behaviors (e.g., hysteria, agitation, apathy), request for information, expressing concerns about managing the condition.

- Related to: Potential for prolonged immobilization (e.g., cast, brace), pressure from assistive devices, altered sensation, presence of swelling.

- As evidenced by: (This is a "risk for" diagnosis, so there are no direct "as evidenced by" statements of actual impairment, but rather risk factors present).

- Related to: Complexity of therapeutic regimen, perceived barriers to following treatment plan, lack of perceived seriousness of the condition, insufficient knowledge.

- As evidenced by: (Again, a "risk for" diagnosis. Risk factors include potential non-adherence to R.I.C.E. protocol, physical therapy exercises, medication regimen, or activity modifications).

- Related to: Inadequate pain management, prolonged inflammation, lack of adherence to treatment regimen, potential for re-injury.

- As evidenced by: (Risk factors for developing chronic pain, such as untreated acute pain or continued aggravating activities).

Nursing interventions for tendonitis are designed to alleviate symptoms, promote healing, educate the patient, and prevent recurrence. These interventions often integrate the medical management strategies discussed earlier with a focus on patient education and support.

- Assess Pain: Regularly assess the patient's pain level using a pain scale (e.g., 0-10), location, characteristics, and aggravating/alleviating factors.

- Administer Analgesics/NSAIDs: Provide prescribed oral pain medications (e.g., acetaminophen, NSAIDs) and topical NSAID gels as ordered, monitoring for effectiveness and side effects.

- Apply R.I.C.E.:

- Rest: Educate the patient on the importance of rest and activity modification. Help them identify activities that aggravate the tendon and suggest alternatives or modifications.

- Ice: Instruct on proper ice application (15-20 minutes, several times a day, with a barrier), explaining its benefits for reducing pain and swelling.

- Compression: Apply compression bandages as needed, ensuring they are snug but do not impair circulation. Teach the patient how to apply and remove them safely.

- Elevation: Encourage elevation of the affected limb, particularly when resting, to reduce swelling.

- Positioning: Assist the patient in finding comfortable positions that reduce stress on the affected tendon.

- Heat vs. Cold: Educate the patient on when to use cold (acute pain/inflammation) versus when heat might be beneficial (chronic stiffness/soreness, but usually after the acute inflammatory phase).

- Assistive Devices: Provide and educate on the safe use of splints, braces, crutches, or other assistive devices as prescribed, ensuring proper fit and function.

- Range of Motion (ROM): Perform passive or assist with active range of motion exercises as tolerated, within pain limits, to prevent stiffness and maintain joint mobility.

- Referral to Physical Therapy (PT) / Occupational Therapy (OT): Collaborate with PT/OT for a structured exercise program focusing on:

- Stretching to improve flexibility.

- Strengthening exercises for supporting muscles.

- Eccentric loading exercises (if appropriate for the specific tendon).

- Functional training to restore specific activities.

- Encourage Gradual Activity: Guide the patient on gradually increasing activity levels as pain subsides, emphasizing that rushing can lead to re-injury.

- Condition Explanation: Explain the nature of tendonitis, its causes, and the rationale behind the treatment plan in clear, understandable language.

- Medication Education: Review all prescribed medications, including dosage, frequency, potential side effects, and warning signs (e.g., GI bleeding with NSAIDs).

- Prevention Strategies: Teach comprehensive preventative measures:

- Proper warm-up and cool-down routines.

- Correct body mechanics and posture for daily activities, work, and sports.

- Importance of gradual progression in activities.

- Ergonomic adjustments for work/home environment.

- Regular stretching and strengthening exercises.

- Using appropriate equipment (e.g., footwear, sports gear).

- Listening to their body and resting when needed.

- Signs of Worsening Condition: Instruct the patient on when to seek medical attention (e.g., increased pain, swelling, numbness, fever, signs of infection).

- Importance of Adherence: Emphasize the importance of adhering to the treatment plan, including PT exercises, for optimal recovery and prevention of chronic issues.

- Infection: Monitor surgical sites (if applicable) or injection sites for signs of infection (redness, warmth, increased pain, pus, fever).

- Skin Integrity: If immobilized in a cast or splint, regularly assess skin for pressure areas, redness, breakdown, or irritation.

- Neurovascular Status: Assess for changes in sensation, circulation, or motor function distal to the affected area, especially if swelling is significant or a device is applied.

- Adverse Drug Reactions: Monitor for side effects of medications (e.g., gastrointestinal upset, allergic reactions).

- Acknowledge Frustration: Acknowledge the patient's potential frustration, anxiety, or fear related to pain, activity limitations, and the recovery process.

- Encourage Realistic Expectations: Help set realistic expectations for recovery time and the importance of patience.

- Referrals: If appropriate, refer to support groups or mental health professionals if chronic pain or disability significantly impacts the patient's emotional well-being.