Table of Contents

ToggleIntroduction to Unconsciousness (Coma)

Unconsciousness represents a fundamental failure of the brain's ability to integrate and process information from the internal and external environment, leading to a state of unresponsiveness. It is a neurological emergency that demands immediate attention, as its underlying causes can be life-threatening and rapidly progressive. Unlike normal sleep, which is a physiological state of reduced consciousness from which one can be easily aroused, unconsciousness implies a pathological disruption of brain function.

The human brain maintains consciousness through a complex interplay of structures. Primarily, these include the cerebral hemispheres, responsible for cognitive functions, awareness, and volitional control, and the Ascending Reticular Activating System (ARAS), a network of neurons located in the brainstem that projects to the cerebral cortex and thalamus, responsible for regulating wakefulness and arousal. Damage or dysfunction to either of these critical components—diffuse dysfunction of both cerebral hemispheres, or focal injury to the ARAS in the brainstem—can result in unconsciousness.

Key Characteristics and Clinical Significance:

- Symptom, Not a Disease: It is important to note that unconsciousness, particularly coma, is a symptom of an underlying medical emergency, not a diagnosis itself.

- Urgency: The onset of unconsciousness signals a severe physiological derangement requiring immediate medical attention. Time-sensitive interventions often dictate prognosis.

- Varied Etiologies: The causes are diverse, ranging from traumatic brain injury, stroke, and infections to metabolic disturbances (e.g., hypoglycemia, uremia), toxic exposures (e.g., drug overdose), and prolonged seizures.

- Risk of Complications: Unconscious patients are at high risk for secondary complications, including airway obstruction, aspiration pneumonia, pressure ulcers, and deep vein thrombosis, all of which require meticulous nursing care.

Consciousness is a state of awareness of oneself and the environment.

It has two main components: arousal (wakefulness), which is mediated by the ascending reticular activating system (ARAS), and awareness (content of consciousness), which is mediated by the cerebral hemispheres. Alterations in either of these components can lead to various states of altered consciousness.

It is important to accurately differentiate these states, as their recognition guides assessment and management.

A. Normal Consciousness:

- Alertness: The highest level of consciousness, characterized by full wakefulness, awareness of self and environment, and appropriate responses to stimuli.

B. States of Decreased Arousal (Progressive Depression of Consciousness):

These terms describe a continuum from mild drowsiness to profound unresponsiveness, typically caused by diffuse cerebral dysfunction or brainstem ARAS impairment.

Lethargy:

- Definition: A state of decreased alertness and mental sluggishness. The patient is drowsy but can be easily aroused by verbal or gentle tactile stimulation.

- Characteristics: Responses to commands are present but may be slow or incomplete. The patient may appear sleepy and have reduced spontaneous activity.

Obtundation:

- Definition: A more profound state of drowsiness than lethargy. The patient is difficult to arouse and requires stronger or more constant stimulation (e.g., loud verbal commands, shaking).

- Characteristics: When aroused, responses are often delayed, confused, or minimal. The patient may drift back to sleep quickly when stimulation ceases. Awareness is significantly impaired.

Stupor:

- Definition: A state of deep unresponsiveness from which the patient can be aroused only by vigorous, repeated, and often noxious (painful) stimuli (e.g., sternal rub, nail bed pressure).

- Characteristics: When aroused, the patient's responses are typically limited to simple motor acts (e.g., withdrawal from pain, groaning). Verbal responses are usually absent or incomprehensible. The patient immediately lapses back into unresponsiveness once the noxious stimulus is removed.

Coma:

- Definition: The most severe form of unconsciousness, characterized by a state of prolonged, profound unresponsiveness from which the patient cannot be aroused by any external stimuli, including vigorous noxious stimulation.

- Characteristics:

- Absence of eye opening.

- Absence of verbal responses.

- Absence of purposeful or voluntary motor responses.

- Reflexive or posturing motor responses to pain may be present depending on the level of brain damage (e.g., decorticate or decerebrate posturing).

- Brainstem reflexes (e.g., pupillary, corneal, gag) may be present or absent.

- No sleep-wake cycles.

- Reflects severe dysfunction of both cerebral hemispheres or the ARAS.

C. Related States of Altered Consciousness (Often Differentiated from Coma):

These conditions are distinct from coma, though they may share some clinical features of unresponsiveness. They involve varying degrees of preserved arousal or awareness.

- Definition: A state of wakefulness without awareness. The patient may have spontaneous eye opening, exhibit sleep-wake cycles, and have preserved brainstem reflexes (e.g., pupillary, corneal, swallowing).

- Characteristics: No evidence of sustained, reproducible, purposeful, or voluntary behavioral responses to visual, auditory, tactile, or noxious stimuli. There is no evidence of language comprehension or expression. Often results from severe diffuse cerebral damage with relative preservation of brainstem function.

- Persistent Vegetative State (PVS): If the vegetative state lasts for more than 4 weeks.

- Permanent Vegetative State: If the PVS lasts for more than 3 months for non-traumatic brain injury, or 12 months for traumatic brain injury, the likelihood of recovery is extremely low.

- Definition: A condition of severely altered consciousness in which there is minimal but definite behavioral evidence of self or environmental awareness.

- Characteristics: Unlike VS, MCS patients show inconsistent but reproducible signs of awareness, such as following simple commands, tracking objects, functionally communicative gestures, or having purposeful affective responses (e.g., smiling or crying in response to appropriate emotional stimuli).

- Definition: A rare neurological condition where a patient is fully conscious and aware but unable to communicate verbally or move most of their body due to complete paralysis of all voluntary muscles, except for vertical eye movements or blinking.

- Characteristics: The patient is fully awake and cognitively intact but "locked in" their body. It typically results from a lesion in the ventral pons (often brainstem stroke), disrupting corticospinal and corticobulbar tracts.

- Definition: Irreversible cessation of all functions of the entire brain, including the brainstem. It is considered legal death.

- Characteristics: Absence of all brainstem reflexes (e.g., pupillary, corneal, oculocephalic, oculovestibular, gag, cough), apnea (absence of spontaneous breathing), and usually a flat electroencephalogram (EEG). Confirmation requires strict clinical criteria and often confirmatory tests.

Summary Table of Consciousness States:

| State | Arousal (Wakefulness) | Awareness (Content) | Eye Opening | Voluntary Motor | Communication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alert | Present | Present | Spontaneous | Present | Present |

| Lethargy | Reduced | Reduced | Spontaneous | Slowed | Present (slow) |

| Obtundation | Reduced | Significantly Impaired | With stimulation | Delayed/Confused | Minimal/Absent |

| Stupor | Severely Reduced | Absent | To noxious stimuli | Withdrawal | Absent |

| Coma | Absent | Absent | Absent | Absent/Reflexive | Absent |

| Vegetative | Present (sleep-wake) | Absent | Spontaneous | Reflexive | Absent |

| Minimally Conscious | Present (inconsistent) | Inconsistent but definite | Spontaneous/To stimuli | Inconsistent purposeful | Inconsistent |

| Locked-in | Present | Present | Spontaneous | Vertical eye movements only | Eye movements only |

| Brain Death | Absent | Absent | Absent | Absent | Absent |

Neuroanatomy & Physiology of Consciousness

Consciousness is a complex emergent property of the brain, typically conceptualized as having two main components: arousal (wakefulness) and awareness (content of consciousness). These components are supported by distinct but interconnected brain regions.

A. Arousal (Wakefulness): The Role of the Ascending Reticular Activating System (ARAS)

Arousal refers to the state of being awake and alert. It is primarily mediated by the Ascending Reticular Activating System (ARAS), a diffuse network of neurons located in the brainstem.

- Location: The ARAS extends from the medulla, through the pons and midbrain, and projects rostrally to the thalamus, hypothalamus, and directly to the cerebral cortex.

- Function: The ARAS acts like a "switch" or "volume control" for wakefulness. It continuously sends excitatory signals to the cerebral cortex, keeping it active and alert. Damage to the ARAS, even if relatively small, can result in profound unconsciousness (coma) because it disrupts this widespread cortical activation.

- Key Neurotransmitters: Several neurotransmitter systems within the ARAS play crucial roles:

- Acetylcholine: Projections from the pontine and basal forebrain cholinergic nuclei are vital for cortical activation.

- Norepinephrine: Neurons in the locus coeruleus contribute to wakefulness and attention.

- Serotonin: Raphe nuclei project widely and influence sleep-wake cycles.

- Dopamine: Ventral tegmental area projections modulate arousal and motivation.

- Histamine: Tuberomammillary nucleus in the hypothalamus promotes wakefulness.

- Orexin (Hypocretin): Hypothalamic neurons releasing orexin are essential for maintaining wakefulness and preventing narcolepsy.

B. Awareness (Content of Consciousness): The Role of the Cerebral Hemispheres and Their Connections

Awareness refers to the ability to integrate information from the internal and external environment, to process thoughts, feelings, and perceptions, and to respond meaningfully. It represents the "content" of consciousness.

- Cerebral Hemispheres: The integrity of both cerebral hemispheres, particularly the cerebral cortex, is essential for awareness. Extensive damage to one hemisphere or diffuse dysfunction of both hemispheres can impair awareness.

- Thalamus: The thalamus acts as a crucial relay station, filtering and transmitting sensory information to the cortex and playing a key role in cortical activation and integration. Thalamocortical loops are critical for maintaining conscious thought.

- Cortico-Cortical Connections: Extensive reciprocal connections between different cortical areas (e.g., frontal, parietal, temporal lobes) allow for the integration of sensory input, memory, emotion, and executive functions, forming the rich tapestry of conscious experience.

- Cortico-Subcortical Loops: Interactions between the cortex and subcortical structures (e.g., basal ganglia, limbic system) also contribute to complex cognitive processes and emotional aspects of awareness.

C. Pathophysiology of Unconsciousness:

Unconsciousness arises when there is a significant disruption to either the ARAS (causing loss of arousal) or widespread bilateral cerebral hemisphere function (causing loss of awareness, even if arousal mechanisms are somewhat intact).

- Brainstem Lesions: Direct damage to the ARAS in the midbrain or pons (e.g., due to stroke, hemorrhage, tumor) can directly impair arousal and lead to coma.

- Bilateral Cortical Lesions: Extensive damage to both cerebral hemispheres (e.g., severe traumatic brain injury, global ischemia, large bilateral strokes, anoxia) can lead to loss of awareness, even if the brainstem is intact.

- Supratentorial Mass Lesions with Herniation: Large lesions above the tentorium cerebelli (e.g., subdural hematoma, epidural hematoma, large cerebral infarct with edema, tumor) can cause a secondary compression and dysfunction of the brainstem, specifically the ARAS, as brain tissue shifts and herniates downwards. This is a common mechanism for coma progression.

- Infratentorial Lesions: Lesions below the tentorium (e.g., cerebellar hemorrhage, brainstem tumor) can directly compress or destroy the ARAS.

- These conditions cause widespread dysfunction of cortical neurons and/or disrupt neurotransmitter systems, affecting both arousal and awareness. The ARAS itself is usually structurally intact but functionally suppressed.

- Examples include hypoglycemia, hyponatremia, uremia, hepatic encephalopathy, drug overdose, infections (meningitis, encephalitis), anoxia, and severe electrolyte imbalances.

- In these cases, if the underlying cause is reversed, brain function and consciousness can often recover fully, unlike severe structural damage.

Etiology (Causes of Coma)

Coma is a neurological emergency with a broad range of potential causes. These causes can generally be categorized as either structural (due to a physical lesion or injury within the brain) or diffuse/metabolic/toxic (due to widespread brain dysfunction without a focal lesion, often reversible). A systematic approach to identifying the etiology is critical for effective management.

A. Structural Causes:

These involve physical damage to brain tissue, leading to direct impairment of the cerebral hemispheres or the ARAS, or indirect compression of these vital structures.

- Concussion/Diffuse Axonal Injury (DAI): Widespread shearing forces from acceleration-deceleration injuries can disrupt axonal connections throughout the white matter, leading to widespread brain dysfunction and coma.

- Intracranial Hemorrhage:

- Epidural Hematoma (EDH): Bleeding between the dura mater and the skull, often arterial, causing rapid compression.

- Subdural Hematoma (SDH): Bleeding between the dura mater and arachnoid mater, often venous, can be acute (rapid onset) or chronic (slowly developing).

- Intracerebral Hemorrhage (ICH): Bleeding within the brain parenchyma, which can be due to trauma, hypertension, or vascular malformations.

- Subarachnoid Hemorrhage (SAH): Bleeding into the subarachnoid space, often from a ruptured aneurysm or trauma.

- Cerebral Contusions: Bruising of brain tissue, often associated with TBI.

- Skull Fractures: Can lead to intracranial hemorrhage or direct brain injury.

- Ischemic Stroke: Large cerebral infarcts, especially if they are bilateral or involve critical areas like the brainstem (e.g., basilar artery occlusion), can cause coma. Extensive cerebral edema following a large infarct can also lead to herniation.

- Hemorrhagic Stroke: Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) or subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) can cause rapid increases in intracranial pressure (ICP), direct brainstem compression, or widespread brain dysfunction due to blood irritating brain tissue.

- Cerebral Venous Sinus Thrombosis: Clotting in the brain's venous drainage system, leading to venous infarction and edema.

- Primary Brain Tumors: Grow within the brain tissue.

- Metastatic Brain Tumors: Spread from cancer elsewhere in the body.

- Tumors can cause coma by direct compression of critical brain structures, causing edema, obstructing cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) flow (hydrocephalus), or causing hemorrhage within the tumor.

- Meningitis: Inflammation of the meninges, causing diffuse cerebral dysfunction due to inflammation and increased ICP.

- Encephalitis: Inflammation of the brain parenchyma itself, often viral, leading to widespread neuronal damage and dysfunction.

- Brain Abscess: A collection of pus within the brain, acting as a mass lesion.

- An abnormal accumulation of CSF within the brain's ventricles, causing increased ICP and compression of brain tissue. Can be obstructive or communicating.

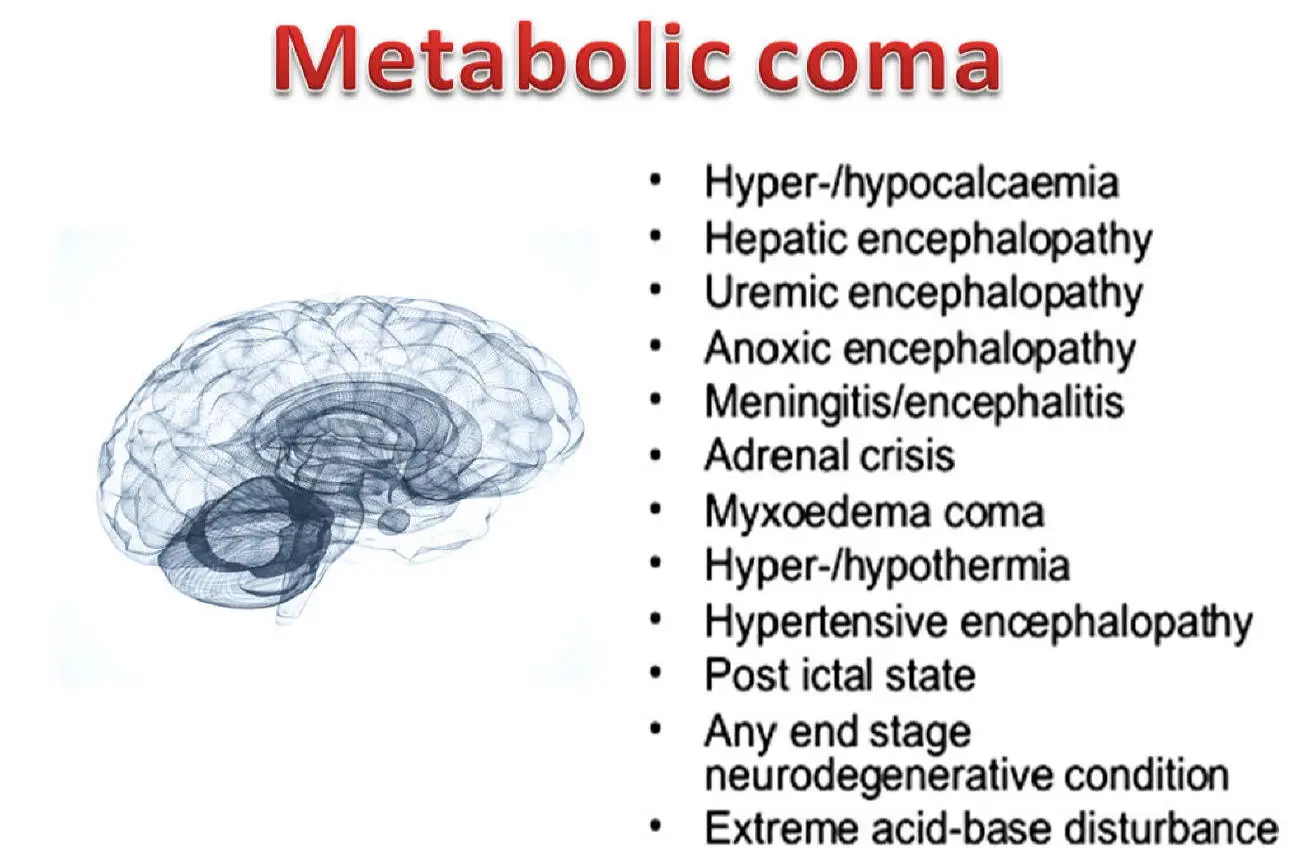

B. Diffuse/Metabolic/Toxic Causes:

These conditions typically affect brain function globally, often without a focal lesion. They are frequently reversible if the underlying cause is identified and treated promptly.

- Hypoglycemia/Hyperglycemia: Critically low or high blood glucose levels.

- Hyponatremia/Hypernatremia: Abnormal sodium levels, leading to cellular swelling or shrinkage.

- Hepatic Encephalopathy: Liver failure leading to accumulation of toxins (e.g., ammonia) in the bloodstream.

- Uremic Encephalopathy: Kidney failure leading to accumulation of metabolic waste products.

- Hypoxia/Anoxia: Lack of oxygen to the brain, often from cardiac arrest, respiratory failure, or severe anemia.

- Hypercapnia/Hypocapnia: Critically high or low carbon dioxide levels.

- Acidosis/Alkalosis: Severe pH imbalances.

- Thyroid Disorders: Hypothyroidism (myxedema coma) or hyperthyroidism (thyroid storm).

- Adrenal Crisis: Adrenal insufficiency.

- Electrolyte Imbalances: E.g., severe hypokalemia, hypercalcemia.

- Overdose (Prescription, Illicit, or Over-the-Counter): Opioids, benzodiazepines, barbiturates, alcohol, tricyclic antidepressants, anticholinergics, sedatives, hypnotics.

- Toxins: Carbon monoxide poisoning, heavy metals, pesticides.

- Withdrawal Syndromes: Severe alcohol withdrawal (delirium tremens), sedative withdrawal.

- Sepsis: Severe systemic infection leading to organ dysfunction, including encephalopathy.

- Septic Encephalopathy: Direct effect of inflammatory mediators and toxins on brain function.

- Status Epilepticus: Prolonged or recurrent seizures without full recovery of consciousness between them.

- Post-ictal State: The period immediately following a seizure, during which the patient may be confused, drowsy, or unarousable for minutes to hours.

- Severe Hypothermia: Core body temperature significantly below normal.

- Severe Hyperthermia: Heat stroke.

- Wernicke's Encephalopathy: Thiamine (Vitamin B1) deficiency, often seen in chronic alcoholics.

C. Other Causes:

- Psychogenic Unresponsiveness: A non-organic cause where the patient appears unconscious but is physiologically awake. Requires careful differentiation (e.g., eyelid resistance to opening, normal brainstem reflexes, abnormal EEG pattern).

- Locked-in Syndrome: As discussed, conscious but unable to move.

- Vertebrobasilar Insufficiency: Severe compromise of blood flow to the brainstem.

Assessment of the Comatose Patient

The assessment of an unconscious patient is an urgent process requiring a systematic and thorough approach. The primary goals are to:

- Stabilize the patient (ABC - Airway, Breathing, Circulation).

- Identify the cause of unconsciousness.

- Prevent secondary brain injury.

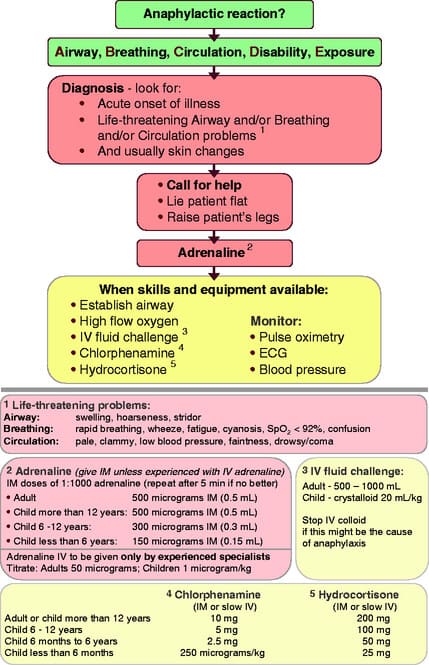

A. Initial Assessment and Stabilization (ABCDE Approach):

- Airway (A):

- Assess: Patency of the airway. Is the tongue obstructing? Are there foreign bodies, blood, or vomit?

- Intervene: Jaw-thrust or chin-lift maneuver, suctioning, oral or nasopharyngeal airway insertion. Endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation may be necessary if airway is compromised or for airway protection (e.g., GCS < 8).

- Breathing (B):

- Assess: Respiratory rate, depth, effort, symmetry of chest rise, breath sounds. Are there abnormal breathing patterns (e.g., Cheyne-Stokes, Kussmaul, apneustic, ataxic)?

- Intervene: Administer supplemental oxygen. Assist ventilation if inadequate. Treat underlying respiratory compromise.

- Circulation (C):

- Assess: Heart rate, blood pressure, rhythm, skin color/temperature, capillary refill time.

- Intervene: Establish IV access. Administer IV fluids for hypotension. Treat arrhythmias. Control external hemorrhage. Monitor cardiac function.

- Disability (D) - Neurological Assessment:

- Assess: Level of consciousness (using GCS), pupillary response, motor response, brainstem reflexes. Perform a rapid neurological screen.

- Intervene: Administer empirical therapies if indicated (e.g., glucose for hypoglycemia, naloxone for opioid overdose, thiamine for Wernicke's). Protect cervical spine if trauma is suspected.

- Exposure (E):

- Assess: Remove clothing to fully inspect for injuries, rashes, needle marks, medical alert bracelets.

- Intervene: Maintain normothermia; cover with blankets after examination.

B. History Taking (from Collateral Sources):

Since the patient is unable to communicate, gathering a detailed history from family, friends, witnesses, paramedics, or medical records is crucial.

- Onset: Acute or gradual?

- Preceding Events: Trauma, falls, headaches, seizures, fevers, weakness, vomiting, drug ingestion?

- Past Medical History: Diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, stroke, kidney/liver disease, psychiatric conditions?

- Medications: Current prescriptions, over-the-counter drugs, illicit drugs, recent changes?

- Allergies:

- Social History: Alcohol use, drug use, recent travel.

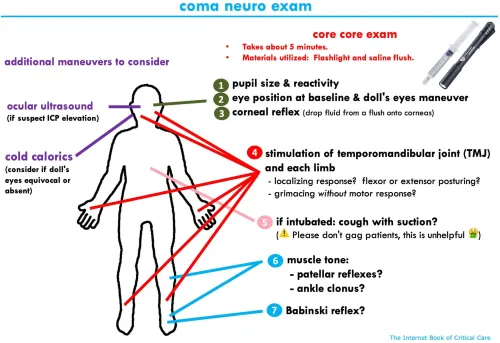

C. Detailed Neurological Examination:

This systematic examination helps to localize the lesion and determine the severity of brain dysfunction.

Level of Consciousness - Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS):

| Component | Score | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Eye Opening (E) | 4 | Spontaneous |

| 3 | To speech | |

| 2 | To pain | |

| 1 | None | |

| Verbal Response (V) | 5 | Oriented to time, place, and person |

| 4 | Confused conversation | |

| 3 | Inappropriate words | |

| 2 | Incomprehensible sounds | |

| 1 | None | |

| Motor Response (M) | 6 | Obeys commands |

| 5 | Localizes to pain | |

| 4 | Withdraws from pain | |

| 3 | Flexion (decorticate posturing) | |

| 2 | Extension (decerebrate posturing) | |

| 1 | None |

Pupillary Response:

- Assess: Size, shape, symmetry, and reactivity to light (direct and consensual).

- Significance:

- Small, reactive: Metabolic encephalopathy, opioid overdose, pontine lesion.

- Dilated, fixed unilateral: Uncal herniation (compression of oculomotor nerve - CN III). NEUROLOGICAL EMERGENCY.

- Mid-position, fixed bilateral: Midbrain damage.

- Pinpoint (1mm), non-reactive: Pontine lesion (usually from hemorrhage) or opioid overdose.

- Irregular: Prior trauma, surgery, or underlying pathology.

Oculomotor Responses (Brainstem Reflexes):

- Doll's Eyes (Oculocephalic Reflex):

- Procedure: Hold eyelids open, rapidly turn head from side to side.

- Normal (Positive): Eyes move opposite to head turning (conjugate movement). Indicates intact brainstem.

- Abnormal (Negative): Eyes remain fixed in mid-position or move with the head. Indicates brainstem dysfunction.

- Contraindication: Do NOT perform if cervical spine injury is suspected.

- Caloric Reflex (Oculovestibular Reflex):

- Procedure: Elevate head 30 degrees. Inject 30-50 mL of ice water into one ear canal (ensure tympanic membrane is intact). Observe eye movement. Wait 5 minutes before testing other ear.

- Normal (Positive): Eyes slowly deviate towards the irrigated ear, with nystagmus away in conscious patients. In unconscious patients, only tonic deviation towards the irrigated ear. Indicates intact brainstem.

- Abnormal (Negative): No eye movement. Indicates brainstem dysfunction.

Motor Response:

- Assess: Spontaneous movement, response to noxious stimuli (sternal rub, nail bed pressure).

- Observe for:

- Purposeful movement: Withdrawal from pain, localization of pain.

- Decorticate Posturing (Flexor Posturing): Arms flexed, adducted, internal rotation; legs extended, internal rotation, plantar flexion. Indicates damage to corticospinal tracts above the red nucleus (midbrain).

- Decerebrate Posturing (Extensor Posturing): Arms extended, adducted, pronated; legs extended, plantar flexion. Indicates more severe damage, typically to the brainstem below the red nucleus (pons/midbrain).

- Flaccid Paralysis: No motor response, indicates very severe brainstem or spinal cord damage.

Brainstem Reflexes:

- Corneal Reflex: Touch cornea with a wisp of cotton.

- Normal: Bilateral blink.

- Gag Reflex: Stimulate posterior pharynx.

- Normal: Gagging/retching.

- Cough Reflex: Suctioning trachea.

- Normal: Cough.

D. Pain Assessment in Unconscious Patients (FLACC Scale):

Since verbal communication of pain is impossible, behavioral pain scales are used. The FLACC (Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, Consolability) Pain Scale is commonly used in non-verbal patients, including adults in critical care, children, and those with developmental delays.

| Component | Score | Description |

|---|---|---|

| F - Face | 0 | No particular expression or smile |

| 1 | Occasional frown, withdrawn, disinterested | |

| 2 | Frequent to constant frown, clenched jaw, quivering chin | |

| L - Legs | 0 | Normal position or relaxed |

| 1 | Uneasy, restless, tense | |

| 2 | Kicking, legs drawn up | |

| A - Activity | 0 | Lying quietly, normal position, moves easily |

| 1 | Squirming, shifting back and forth, tense | |

| 2 | Arched, rigid, jerking | |

| C - Cry | 0 | No cry (awake or asleep) |

| 1 | Moans or whimpers, occasional complaint | |

| 2 | Crying steadily, screams or sobs, frequent complaints | |

| C - Consolability | 0 | Content, relaxed |

| 1 | Reassured by occasional touching, hugging, or talking to; distractible | |

| 2 | Difficult to console or comfort |

E. Initial Diagnostic Investigations:

Concurrent with the physical assessment, rapid diagnostic tests are initiated:

- Blood Glucose: STAT check for hypoglycemia/hyperglycemia.

- Electrolytes: Sodium, potassium, calcium, magnesium.

- Renal Function: BUN, creatinine.

- Liver Function: AST, ALT, bilirubin, ammonia.

- Arterial Blood Gases (ABGs): pH, pO2, pCO2, bicarbonate.

- Complete Blood Count (CBC): Anemia, infection.

- Coagulation Studies: PT/INR, PTT (especially if hemorrhage or anticoagulant use is suspected).

- Toxicology Screen: Urine and serum (drugs, alcohol, specific toxins).

- Thyroid Function Tests: If endocrine pathology suspected.

- Blood Cultures: If infection suspected.

- Non-contrast Head CT: Often the first and most critical imaging study. Rapidly identifies acute hemorrhage (intracranial, subarachnoid, epidural, subdural), major ischemic stroke (early signs), mass lesions, hydrocephalus, and skull fractures. Essential for differentiating structural from metabolic causes.

- Cervical Spine CT/X-ray: If trauma is suspected.

- CT Angiography (CTA) / CT Perfusion (CTP): If acute stroke is suspected.

- MRI Brain: More detailed imaging, useful for identifying subtle lesions, posterior fossa lesions, and diffuse white matter injury (e.g., DAI), but takes longer and may not be feasible in unstable patients.

- Electrocardiogram (ECG): To assess for cardiac arrhythmias, ischemia, or conduction abnormalities that could cause syncope or affect brain perfusion.

- Lumbar Puncture (LP): If meningitis or encephalitis is suspected after imaging rules out increased ICP. CSF analysis can reveal infection, inflammation, or SAH not seen on CT.

- Electroencephalogram (EEG): To detect non-convulsive seizures (non-convulsive status epilepticus), assess background brain activity, or confirm brain death.

Prioritize Management Strategies

The management of a comatose patient is often a race against time, requiring simultaneous diagnostic evaluation and therapeutic intervention. The priorities are always to stabilize the patient, prevent secondary brain injury, and treat the underlying cause.

A. General Supportive Care (Initial Resuscitation - ABCDE Re-emphasized):

These are the foundational interventions applicable to all comatose patients, irrespective of the underlying cause, and are often initiated concurrently with the initial assessment.

- Secure Airway: If GCS is ≤ 8 or there's evidence of airway compromise (obstruction, aspiration risk, hypovilation), endotracheal intubation is typically indicated.

- Mechanical Ventilation: Control CO2 levels (maintain normocapnia, PCO2 35-45 mmHg, to optimize cerebral blood flow without causing vasoconstriction or vasodilation) and oxygenation (PaO2 > 60 mmHg or SpO2 > 94%).

- Head of Bed Elevation: Elevate the head of the bed to 30 degrees to promote venous drainage from the brain and help reduce intracranial pressure (ICP), unless contraindicated by spinal injury or severe hypotension.

- Maintain Normotension: Avoid hypotension, which can lead to cerebral hypoperfusion and secondary brain injury. Maintain cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP) > 60-70 mmHg (CPP = MAP - ICP).

- IV Fluids: Administer isotonic crystalloids (e.g., normal saline) to maintain euvolemia. Avoid hypotonic solutions, which can worsen cerebral edema.

- Vasopressors: Use if needed to maintain adequate mean arterial pressure (MAP) after fluid resuscitation.

- Monitor Cardiac Rhythm: Treat arrhythmias.

- Prevent Hyperthermia: Fever increases cerebral metabolic demand and can worsen brain injury. Actively cool if present (antipyretics, cooling blankets).

- Manage Hypothermia: If present, rewarm gradually. Therapeutic hypothermia may be indicated in specific situations (e.g., post-cardiac arrest).

- Glucose Management: Immediately correct hypoglycemia (administer D50 IV) or severe hyperglycemia (insulin).

- Electrolyte Correction: Address severe hyponatremia, hypernatremia, hyperkalemia, hypokalemia, etc.

- Nutritional Support: Initiate early enteral nutrition, typically within 24-48 hours.

- Nasogastric Tube: Decompress the stomach to prevent aspiration and facilitate feeding.

- Stress Ulcer Prophylaxis: H2 blockers or proton pump inhibitors.

- Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT) Prophylaxis: Sequential compression devices (SCDs), low-molecular-weight heparin or unfractionated heparin (unless contraindicated by hemorrhage).

- Skin Care: Regular repositioning to prevent pressure ulcers.

- Eye Care: Lubricating drops/ointment to prevent corneal abrasion.

B. Specific Interventions Based on Etiology:

Once a suspected or confirmed diagnosis is made, targeted therapies are initiated.

- External Ventricular Drain (EVD) / ICP Monitor: For direct ICP measurement and CSF drainage.

- Osmotic Therapy:

- Mannitol: IV boluses to draw fluid from brain tissue into the circulation.

- Hypertonic Saline (3% or 23.4%): Alternative osmotic agent, more effective in some cases.

- Sedation & Analgesia: To reduce metabolic demand and prevent ICP spikes (propofol, midazolam, fentanyl).

- Neuromuscular Blockade: If sedation alone is insufficient to control ICP.

- Barbiturate Coma: In refractory ICP elevation, to reduce cerebral metabolic rate and ICP.

- Decompressive Craniectomy: Surgical removal of part of the skull to allow brain swelling, for refractory ICP.

- Rapid Evacuation of Hematomas: For EDH, acute SDH, or large ICH.

- ICP Management: As above.

- Ischemic Stroke:

- Thrombolysis (IV tPA): If criteria met and within time window.

- Endovascular Thrombectomy: For large vessel occlusions.

- Blood Pressure Management: Often permissive hypertension initially to maintain cerebral perfusion, then control to prevent hemorrhagic transformation.

- Hemorrhagic Stroke (ICH/SAH):

- Blood Pressure Control: Aggressive management to prevent rebleeding and hematoma expansion.

- Reversal of Anticoagulation: If applicable (Vitamin K, PCC, specific reversal agents).

- Aneurysm Clipping/Coiling: For SAH.

- ICP Management: As above.

- Empirical Antibiotics/Antivirals: Administer immediately after blood cultures and lumbar puncture (if safe to perform).

- Antipyretics: To control fever.

- Steroids: Dexamethasone for bacterial meningitis.

- Antidotes:

- Naloxone: For opioid overdose.

- Flumazenil: For benzodiazepine overdose (use with caution, can precipitate seizures).

- Correction of Metabolic Derangements:

- Glucose: D50 for hypoglycemia.

- Electrolyte Correction: Slow and careful correction of sodium imbalances to prevent osmotic demyelination syndrome.

- Thiamine: For suspected Wernicke's encephalopathy (alcoholics).

- Removal of Toxins:

- Activated Charcoal: For recent oral ingestions.

- Hemodialysis: For severe renal failure (uremia), some drug intoxications (e.g., methanol, lithium, salicylate).

- Supportive Care: Manage withdrawal syndromes, control seizures.

- Anticonvulsants: Benzodiazepines (lorazepam, midazolam) acutely, followed by fosphenytoin, levetiracetam, valproate, or propofol/midazolam infusion for refractory status.

C. Ongoing Monitoring:

- Continuous Neurological Assessment: Frequent GCS, pupillary checks, motor response.

- Vital Signs: Continuous cardiac monitoring, blood pressure, SpO2, temperature.

- ICP Monitoring: If indicated.

- Laboratory Trends: Repeat blood work to monitor response to therapy.

- Imaging: Repeat CT/MRI if neurological status changes or to assess treatment efficacy.

Prognosis and Recovery

Predicting the outcome for a comatose patient is one of the most challenging aspects of critical care neurology. Prognosis is highly variable, depending on the underlying cause, severity and duration of brain injury, and the patient's age and pre-morbid health status. Recovery can range from full neurological return to persistent vegetative state (PVS), minimally conscious state (MCS), or death.

A. Factors Influencing Prognosis:

Several factors are consistently associated with a better or worse prognosis:

- Better Prognosis: Coma due to reversible metabolic/toxic causes (e.g., hypoglycemia, drug overdose, hepatic encephalopathy) generally has a better prognosis if the underlying cause is promptly identified and treated.

- Worse Prognosis: Coma due to severe structural brain damage (e.g., extensive anoxic brain injury, large intracerebral hemorrhage, severe traumatic brain injury) or prolonged ischemia often carries a poorer prognosis.

- GCS Score: Lower GCS scores (e.g., GCS 3-5) are generally associated with worse outcomes, particularly if sustained.

- Duration: Prolonged coma (e.g., more than a few days to weeks) without significant improvement suggests a poorer chance of good neurological recovery.

- Pupillary Light Reflex (PLR): Bilaterally absent pupillary light reflexes after 24-72 hours (especially post-anoxic injury) are a strong predictor of poor outcome.

- Corneal Reflex: Absent corneal reflexes indicate deeper brainstem dysfunction and a poorer prognosis.

- Motor Response: Absent or extensor motor responses (decerebrate posturing) are associated with worse outcomes than withdrawal or localization to pain. Flaccidity is the worst.

- Brainstem Reflexes: Absent oculocephalic and oculovestibular reflexes (Doll's eyes and caloric reflexes) are poor prognostic signs.

B. Prognostic Tools and Biomarkers:

While clinical examination remains paramount, several tools and biomarkers can aid in refining prognosis, especially in specific scenarios like post-anoxic coma.

- CT Scan: Can identify early signs of diffuse cerebral edema, effacement of sulci and cisterns, and loss of gray-white matter differentiation (especially after anoxia), which are associated with poor prognosis.

- MRI (DWI/ADC sequences): Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) can detect early ischemic changes and widespread cytotoxic edema, which are powerful predictors of outcome, particularly in post-anoxic coma.

- Suppressed Background Activity: A severely suppressed EEG background (generalized low amplitude) is a poor prognostic sign.

- Burst-Suppression Pattern: Alternating periods of high-voltage activity and electrical silence are indicative of severe brain dysfunction and often a poor outcome.

- Generalized Periodic Discharges (GPDs): Can be associated with poor outcomes.

- Reactivity: Absence of EEG reactivity to external stimuli is a poor prognostic sign.

- Non-convulsive Status Epilepticus (NCSE): Can occur in comatose patients and needs to be identified and treated, as it can worsen neurological outcome.

- Somatosensory Evoked Potentials (SSEPs): Absence of bilateral cortical SSEPs (N20 potential) in response to median nerve stimulation is a highly specific predictor of poor outcome (PVS or death) in post-anoxic coma. It has a high specificity but lower sensitivity.

- Neuron-Specific Enolase (NSE): Elevated serum NSE levels, especially persistent elevation, are associated with poor neurological outcome after anoxic brain injury.

- S-100B: Another brain-specific protein, though less specific than NSE, can also be elevated in brain injury.

C. States of Altered Consciousness Post-Coma:

If a patient survives coma, they may emerge into one of several chronic states of altered consciousness:

- Definition: Characterized by arousal (eyes open, sleep-wake cycles, ability to grimace, cry, or smile) but no evidence of awareness of self or environment. Reflexive movements are present, but no voluntary interaction.

- Prognosis: If persistent for more than 1 month (PVS), the prognosis for meaningful recovery is poor, especially after 3 months for anoxic injury or 12 months for traumatic injury.

- Definition: Characterized by definitive, but inconsistent, evidence of self- or environmental awareness. This might include following simple commands, intelligible verbalization, or visually pursuing objects.

- Prognosis: Better than VS, with potential for further improvement, though recovery is often protracted and incomplete.

- Definition: Patients are fully conscious and aware but paralyzed, typically retaining only vertical eye movement and blinking. They are "locked in" their bodies.

- Prognosis: While motor recovery is often limited, cognitive prognosis is good, and patients can communicate via assistive devices.

D. Rehabilitation:

- Early Mobilization: As soon as medically stable, to prevent complications like muscle atrophy, contractures, and pressure ulcers.

- Physical Therapy (PT): To improve strength, range of motion, and mobility.

- Occupational Therapy (OT): To improve activities of daily living (ADLs), cognitive function, and fine motor skills.

- Speech and Language Pathology (SLP): For communication, swallowing difficulties (dysphagia), and cognitive retraining.

- Neuropsychology: For cognitive assessment and rehabilitation.

- Psychological Support: For patients and families dealing with the profound changes and long-term implications.

E. Ethical Considerations and End-of-Life Decisions:

In cases of profound and irreversible brain damage, families and healthcare teams often face difficult decisions regarding withdrawal of life support.

- Advanced Directives: Patient's wishes (e.g., living will, durable power of attorney for healthcare) are paramount.

- Futility of Treatment: Discussion regarding medical treatments that offer no reasonable hope of recovery.

- Palliative Care: Focus shifts from curative to comfort care, ensuring dignity and symptom management.

Interventions, and Nursing Diagnoses for the Comatose Patient

Nursing Interventions for the Comatose Patient:

Nursing care focuses on maintaining physiological stability, preventing complications, and supporting the family.

- Frequent GCS Assessment: Hourly or more frequently if unstable, noting trends.

- Pupillary Checks: Size, shape, symmetry, and reaction to light (often hourly).

- Motor Assessment: Response to command or painful stimuli (e.g., central vs. peripheral stimulus).

- Vital Signs: Monitor for Cushing's triad (hypertension, bradycardia, irregular respirations) indicative of increased ICP.

- ICP Monitoring: If an ICP device is in place, monitor waveforms, ICP values, and maintain patency of the system. Calculate and maintain target Cerebral Perfusion Pressure (CPP).

- Maintain Patent Airway: Position patient to prevent aspiration, frequent suctioning of oral and tracheal secretions (if intubated).

- Ventilator Management: Ensure correct settings, humidification, and alarms are active.

- Oxygenation & Ventilation: Monitor SpO2, ABGs, and EtCO2 (if available).

- Prevent Aspiration Pneumonia: Head of bed 30-45 degrees, check gastric residual volumes if tube-fed, maintain cuff pressure if intubated.

- Frequent Repositioning: To promote lung expansion and prevent atelectasis.

- Blood Pressure Control: Administer vasopressors/antihypertensives as ordered to maintain target MAP/CPP.

- Fluid Balance: Monitor I&Os meticulously, central venous pressure (CVP), and administer IV fluids as prescribed. Avoid fluid overload.

- Cardiac Monitoring: Observe for arrhythmias and notify physician.

- Monitor Temperature: Hourly, intervene promptly for hypo/hyperthermia.

- Fever Management: Antipyretics, cooling blankets, ice packs to axilla/groin.

- Hypothermia Management: Warming blankets, warm IV fluids.

- Strict I&Os: Crucial for detecting fluid shifts.

- Monitor Lab Values: Daily electrolytes, BUN/Cr, glucose, osmolality.

- Electrolyte Replacement: Administer as ordered, correcting imbalances carefully.

- Enteral Feedings: Initiate early via NG/OG tube, confirming placement, checking residuals, and ensuring formula tolerance.

- Bowel Management: Prevent constipation (stool softeners, laxatives), check for impaction.

- Stress Ulcer Prophylaxis: Administer H2 blockers or PPIs.

- Meticulous Hand Hygiene:

- Aseptic Technique: For all invasive procedures (IV insertion, Foley care, suctioning, dressing changes).

- Monitor for Signs of Infection: Fever, increased WBC, purulent drainage.

- Foley Catheter Care: Prevent CAUTI.

- Central Line Care: Prevent CLABSI.

- Oral Hygiene: Frequent mouth care to prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP).

- Frequent Repositioning: Every 2 hours (or more frequently) to relieve pressure.

- Skin Assessment: Inspect skin for redness, breakdown.

- Specialty Beds/Mattresses: To reduce pressure.

- Moisture Control: Keep skin clean and dry.

- Passive Range of Motion (PROM): Perform several times a day to all joints to prevent contractures.

- Proper Positioning: Maintain body alignment, use splints/foot boards to prevent foot drop.

- Early Mobilization: Collaborate with PT/OT for out-of-bed activity as soon as stable.

- Lubricating Eye Drops/Ointment: Protect corneas from drying due to absent blink reflex.

- Taping Eyelids Shut: If patient's eyes remain open.

- FLACC Scale: As discussed, for ongoing pain assessment.

- Administer Analgesics/Sedatives: Carefully titrated to achieve comfort without over-sedation that might mask neurological changes.

- Environmental Control: Minimize noise, provide a calm environment.

- Provide Information: Explain procedures and patient status in understandable terms.

- Emotional Support: Acknowledge anxiety, grief, and uncertainty.

- Facilitate Family Presence: Encourage visitation, allow participation in care if appropriate.

- Spiritual Support: Connect family with spiritual care if desired.

- Address Ethical Dilemmas: Facilitate discussions with the medical team regarding prognosis and end-of-life decisions.

C. Nursing Diagnoses for the Comatose Patient:

Nursing diagnoses provide a framework for individualized nursing care plans. Here are some key ones for comatose patients:

- Risk for Ineffective Airway Clearance related to depressed cough/gag reflex, inability to clear secretions, decreased level of consciousness.

- Goals: Patent airway, clear breath sounds, effective gas exchange.

- Risk for Impaired Gas Exchange related to hypoventilation, airway obstruction, aspiration.

- Goals: Optimal oxygenation and ventilation, ABGs within normal limits.

- Risk for Impaired Cerebral Tissue Perfusion related to increased intracranial pressure, decreased mean arterial pressure, cerebral edema.

- Goals: Stable neurological status, ICP within normal limits, CPP > 60-70 mmHg.

- Risk for Deficient Fluid Volume related to osmotic diuretics, altered regulation, or Excess Fluid Volume related to SIADH, renal dysfunction.

- Goals: Euvolemia, balanced I&Os, stable electrolytes.

- Risk for Impaired Skin Integrity related to immobility, pressure, shearing forces, incontinence.

- Goals: Intact skin, absence of pressure ulcers.

- Risk for Imbalanced Nutrition: Less Than Body Requirements related to inability to ingest food, hypermetabolic state, altered absorption.

- Goals: Adequate nutritional intake, stable weight, appropriate lab values.

- Risk for Infection related to invasive lines, altered skin integrity, suppressed immune response, immobility.

- Goals: Absence of infection, normal temperature, WBC count.

- Risk for Injury related to seizures, agitated behavior, impaired neurological function, environmental hazards.

- Goals: Patient free from injury, safe environment.

- Impaired Physical Mobility related to neuromuscular impairment, decreased level of consciousness.

- Goals: Maintenance of joint mobility, prevention of contractures.

- Compromised Family Coping related to critically ill family member, uncertain prognosis, lack of information.

- Goals: Family expresses feelings, participates in decision-making, utilizes support systems.

- Acute Pain (possible) related to underlying injury, medical procedures, immobility (assessed via FLACC or other behavioral scales).

- Goals: Reduction in behavioral signs of pain/discomfort, stable physiological parameters.