Table of Contents

ToggleTHROMBUS AND EMBOLUS

Introduction

The circulatory system is composed of blood vessels and the heart. Blood vessels (arteries and veins) facilitate the passage of blood throughout the body. Blood cells suspended in the plasma travel through blood vessels.

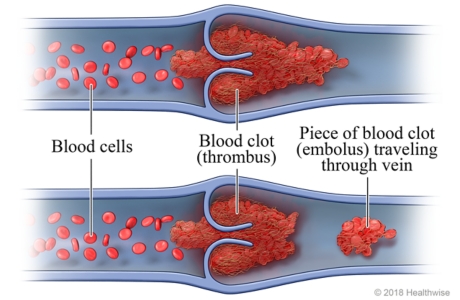

Blood clots are solid masses that travels through the vessels along the blood. They are made up of either platelets, fibrin, fat, amniotic fluid, a tumor or air. Foreign substances such as iodine, cotton, talc or a piece of catheter tube can serve as blood clots. Thrombus and embolus are two terms used interchangeably to describe blood clots.

The main difference between thrombus and embolus is that thrombus refers to a firm mass of blood clot developed within the circulatory system whereas embolus refers to a piece of thrombus that travels through the blood vessels. An embolus travels until it reaches the tiny blood vessels that are too small to pass through it.

THROMBUS

Definition

Thrombus refers to a blood clot formed inside the circulatory system that can impede blood flow. It remains attached to the vessel wall at its site of formation.

Pathophysiology & Virchow's Triad

Generally, a thrombus stays attached to the site of the blood vessel where it is formed. A blood clot can be formed as a result of injury to a blood vessel or tissue. Aggregation of platelets forms a quick plug to prevent bleeding.

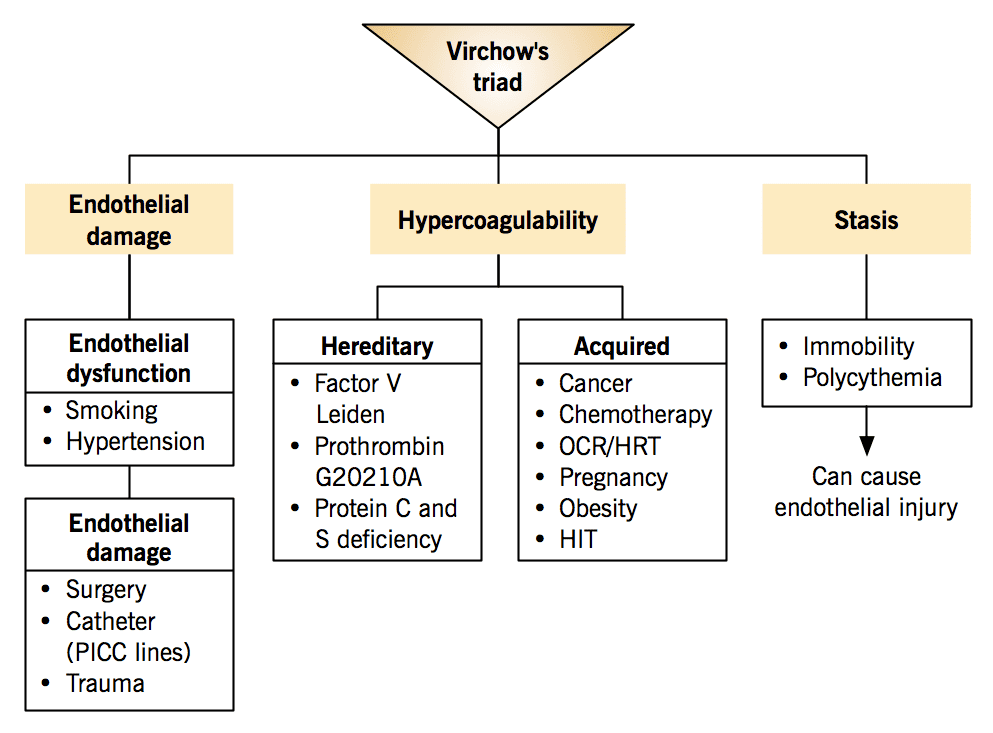

The formation of a thrombus is classically explained by Virchow's Triad, which outlines the three broad categories of factors that contribute to thrombosis:

- Endothelial Injury: Damage to the inner lining (endothelium) of a blood vessel. This is often the most important factor, especially in arterial thrombosis. It exposes underlying collagen and tissue factor, which initiates platelet adhesion, activation, and the coagulation cascade.

- Examples: Atherosclerosis (the most common cause in arteries), hypertension, physical trauma, surgery, indwelling catheters (e.g., IV lines, central lines), inflammation (vasculitis), toxins (e.g., from smoking).

- Stasis of Blood Flow (Abnormal Blood Flow): When blood flow is slow (stasis) or turbulent, platelets and clotting factors can accumulate in specific areas and become activated. Normal, laminar blood flow helps to keep clotting factors diluted and washes away activated clotting factors and platelets.

- Examples of Stasis: Prolonged immobility (e.g., long-haul flights, bed rest, paralysis), heart failure, venous insufficiency, varicose veins, atrial fibrillation (in the heart's atria).

- Examples of Turbulence: Atherosclerotic plaques, aneurysms, valvular heart disease, tortuous blood vessels.

- Hypercoagulability: An abnormal increase in the tendency of blood to clot, due to either an excess of pro-coagulant factors or a deficiency of anti-coagulant factors. This can be inherited (genetic) or acquired.

- Examples of Inherited: Factor V Leiden mutation, Prothrombin gene mutation, deficiencies of Antithrombin, Protein C, or Protein S.

- Examples of Acquired: Cancer (malignancy), pregnancy and postpartum period, oral contraceptives and hormone replacement therapy, dehydration, certain autoimmune diseases (e.g., antiphospholipid syndrome), severe infection (sepsis), major surgery, trauma, inflammatory conditions.

Causes and Risk Factors of a Thrombus

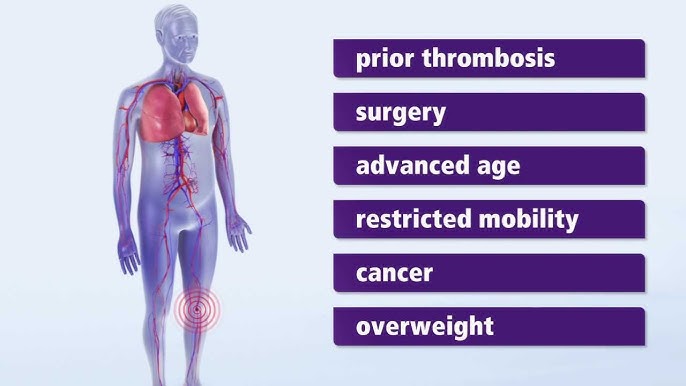

Beyond the elements of Virchow's Triad, specific conditions and lifestyle factors significantly increase the risk of thrombus formation:

- Atherosclerosis: The leading cause of arterial thrombosis. Plaque rupture exposes thrombogenic material, leading to clot formation.

- High Cholesterol (Hyperlipidemia): Contributes to atherosclerosis and endothelial damage.

- Hypertension (High Blood Pressure): Causes direct endothelial injury and promotes atherosclerosis.

- Diabetes Mellitus: Damages blood vessels (microvascular and macrovascular) and promotes a pro-thrombotic state.

- Tobacco Smoking: Directly damages endothelium, increases platelet aggregation, and promotes inflammation and hypercoagulability.

- Obesity and Overweight: Associated with chronic inflammation, insulin resistance, and a hypercoagulable state.

- Sedentary Lifestyle: Leads to blood stasis, especially in the lower extremities, increasing DVT risk.

- Cancer (Malignancy): Many cancers activate the coagulation system, leading to a significantly increased risk of thrombosis (e.g., Trousseau's syndrome).

- Surgery and Trauma: Endothelial injury during surgery and post-operative immobility are major risk factors.

- Prolonged Immobility: Whether due to bed rest, long travel, or paralysis, it promotes venous stasis.

- Atrial Fibrillation: Irregular and often rapid heart rate leads to blood pooling and stasis in the atria, increasing the risk of cardiac thrombus formation, which can then embolize.

- Heart Failure: Reduced cardiac output leads to blood stasis, especially in the venous system.

- Previous Thromboembolic Event: A history of DVT, PE, or stroke significantly increases the risk of recurrence.

- Age: Risk of thrombosis generally increases with age.

- Pregnancy and Postpartum Period: Hormonal changes and physical compression of veins lead to a hypercoagulable state and stasis.

- Certain Medications: Oral contraceptives, hormone replacement therapy, and some chemotherapy agents can increase clotting risk.

- Genetic Predisposition: Inherited thrombophilias (e.g., Factor V Leiden).

- Inflammatory Conditions: Systemic lupus erythematosus, inflammatory bowel disease, vasculitis.

- Dehydration: Can increase blood viscosity, contributing to stasis and hypercoagulability.

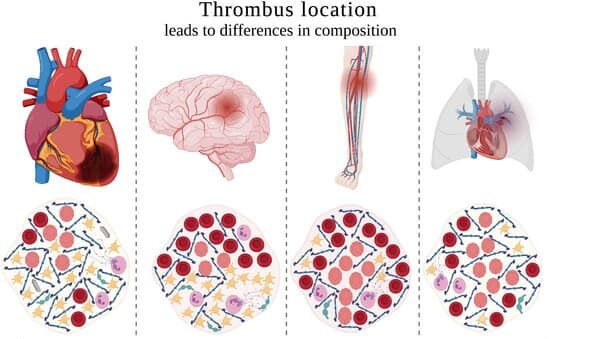

Types of a Thrombus (Classification by Location and Composition)

Depending on the location and primary composition, several types of thrombosis can be identified:

- Arterial Thrombus:

- Formed in arteries, often associated with endothelial injury and turbulent flow due to atherosclerosis.

- Typically "white thrombi" because they are rich in platelets, formed in areas of high blood flow.

- Can lead to conditions like myocardial infarction (heart attack), ischemic stroke, or peripheral arterial occlusion.

- Examples: Coronary artery thrombosis, cerebral artery thrombosis, peripheral artery thrombosis.

- Venous Thrombus:

- Formed in veins, primarily associated with blood stasis and hypercoagulability.

- Typically "red thrombi" because they are rich in fibrin and red blood cells, formed in areas of low blood flow.

- Often results in Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT), which can lead to pulmonary embolism (PE) if the clot embolizes.

- Examples: Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT) in legs, superficial thrombophlebitis.

- Cardiac Thrombus:

- Formed within the chambers of the heart.

- Often seen in conditions like atrial fibrillation (left atrial appendage thrombus), myocardial infarction (mural thrombus in left ventricle), or valvular heart disease.

- Can embolize to systemic arteries (e.g., brain, kidneys, limbs).

- Microvascular Thrombus:

- Formed in very small blood vessels (capillaries, arterioles, venules).

- Often associated with systemic inflammatory states, sepsis, or disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC).

- Can lead to widespread organ damage.

Clinical Manifestations (Signs and Symptoms)

The symptoms of a thrombus occur when the clot restricts or completely blocks blood flow through the vessel, leading to ischemia (lack of oxygen) in the tissues supplied by that vessel. Symptoms vary widely depending on the location and size of the thrombus:

A. Arterial Thrombosis:

Due to sudden or significant reduction in blood flow, leading to tissue ischemia or infarction.

- Coronary Artery Thrombosis (leading to Myocardial Infarction / Heart Attack):

- Severe chest pain, often described as crushing, pressure, or tightness, that may radiate to the arm (usually left), back, neck, jaw, or stomach.

- Shortness of breath.

- Sweating (diaphoresis).

- Nausea and vomiting.

- Lightheadedness or fainting.

- Unstable angina (new onset, increasing, or rest angina).

- Cerebral Artery Thrombosis (leading to Ischemic Stroke):

- Sudden weakness or numbness on one side of the body (face, arm, leg).

- Difficulty speaking or understanding speech (aphasia, dysarthria).

- Sudden vision changes in one or both eyes.

- Sudden severe headache with no known cause.

- Dizziness, loss of balance, or coordination.

- Peripheral Arterial Thrombosis (e.g., in legs/arms):

- Sudden, severe pain in the affected limb.

- Pallor (paleness) of the limb.

- Pulselessness below the occlusion.

- Paresthesia (numbness or tingling).

- Paralysis (in severe cases).

- Poikilothermia (coldness) of the affected limb.

- (The "6 Ps": Pain, Pallor, Pulselessness, Paresthesia, Paralysis, Poikilothermia).

- Mesenteric Artery Thrombosis (affecting intestines):

- Severe, sudden abdominal pain, often disproportionate to physical findings.

- Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea.

- Abdominal distension.

- Bloody stools (later stage).

B. Venous Thrombosis:

Primarily due to impaired venous return and inflammation.

- Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT) (most commonly in lower extremities):

- Swelling of the affected leg or arm.

- Pain or tenderness in the calf or thigh (often described as a cramp or soreness), especially when standing or walking.

- Warmth over the affected area.

- Redness or discoloration of the skin.

- Increased prominence of superficial veins.

- Homan's sign (calf pain on dorsiflexion of the foot) is often cited but unreliable.

- Superficial Thrombophlebitis:

- Red, tender, warm cord-like structure felt under the skin (usually along a varicose vein).

- Less serious than DVT, but can sometimes extend into deep veins.

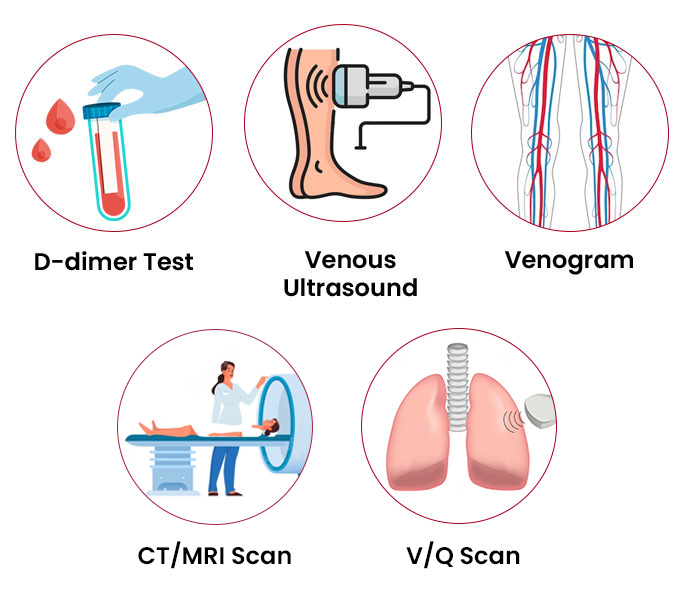

Diagnosis of a Thrombus

Diagnosing a thrombus involves a combination of clinical assessment, blood tests, and imaging studies:

1. Clinical Assessment: Detailed medical history (including risk factors), physical examination for signs and symptoms (e.g., pain, swelling, discoloration, pulses).2. Blood Tests:

- D-dimer: A blood test that measures a degradation product of fibrin. An elevated D-dimer can indicate the presence of a recent or ongoing clot, but it's not specific (can be elevated in many other conditions). A negative D-dimer can often rule out DVT or PE in low-risk patients.

- Coagulation studies: Prothrombin Time (PT), Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time (aPTT), International Normalized Ratio (INR) to assess clotting function and monitor anticoagulant therapy.

- Complete Blood Count (CBC): May show elevated white blood cells in inflammatory states or infection.

- Thrombophilia Screen: If a genetic hypercoagulable state is suspected (e.g., Factor V Leiden, Protein C/S deficiency).

- Duplex Ultrasound: The most common and preferred non-invasive test for DVT. It uses sound waves to visualize blood flow and detect blockages in veins.

- Venography: An invasive X-ray procedure where contrast dye is injected into a vein to visualize the venous system. Less common now due to ultrasound.

- CT Angiography (CTA): Used for diagnosing arterial thrombi (e.g., coronary, cerebral, mesenteric, peripheral arteries) or for pulmonary embolism (CTPA - CT Pulmonary Angiogram). Involves injecting contrast dye and taking detailed X-ray images.

- MR Angiography (MRA): Similar to CTA but uses magnetic fields and radio waves, avoiding radiation. Useful for arterial and venous thrombi.

- Echocardiography: Used to detect thrombi within the heart chambers (e.g., in atrial fibrillation or after myocardial infarction) or to assess cardiac function.

- Angiography (Conventional): An invasive procedure where a catheter is inserted into an artery and dye is injected to visualize the arterial system. Often performed when interventions (e.g., angioplasty, thrombectomy) are planned.

Treatment of a Thrombus

Treatment for a thrombus aims to prevent clot growth, dissolve existing clots, prevent new clots from forming, and manage symptoms. The approach depends on the type, size, and location of the thrombus, as well as the patient's overall health.

- These medications prevent the clot from growing and help prevent new clots from forming. They do not typically dissolve existing clots but allow the body's natural fibrinolytic system to break down the clot over time.

- Examples:

- Heparin (unfractionated and low molecular weight heparin - LMWH): Often used for initial rapid anticoagulation, administered intravenously or subcutaneously.

- Warfarin: An oral anticoagulant, requires regular INR monitoring.

- Direct Oral Anticoagulants (DOACs) / Novel Oral Anticoagulants (NOACs): (e.g., rivaroxaban, apixaban, dabigatran, edoxaban). Do not require frequent monitoring, often preferred for convenience.

- Nursing Considerations: Monitor for bleeding (e.g., bruising, petechiae, blood in urine/stools, epistaxis, gum bleeding), educate patient on bleeding precautions (e.g., soft toothbrush, electric razor, avoid contact sports), and importance of adherence.

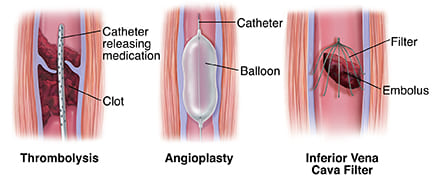

- These potent medications actively dissolve existing clots by activating plasminogen to plasmin, an enzyme that breaks down fibrin.

- Used in acute, severe cases where rapid clot dissolution is critical (e.g., massive pulmonary embolism, acute ischemic stroke, severe arterial occlusion).

- Administered intravenously or directly into the clot via a catheter.

- Nursing Considerations: High risk of bleeding. Close monitoring for signs of hemorrhage, frequent neurological checks if for stroke, and strict adherence to administration protocols. Contraindications (e.g., recent surgery, bleeding disorders, uncontrolled hypertension) must be carefully assessed.

- Primarily used for arterial thrombosis. These medications prevent platelets from clumping together to form a clot.

- Examples: Aspirin, Clopidogrel (Plavix), Ticagrelor (Brilinta), Prasugrel (Effient).

- Nursing Considerations: Similar to anticoagulants regarding bleeding risk. Educate patient on the importance of adherence, especially after stenting or acute coronary syndromes.

- Surgical or endovascular procedures to physically remove the thrombus.

- Thrombectomy: Often used for acute arterial occlusions (e.g., stroke, peripheral arterial occlusion) or massive DVT/PE in select cases. A catheter is guided to the clot, and it's mechanically extracted or aspirated.

- Embolectomy: Surgical removal of an embolus (which originated as a thrombus elsewhere).

- Nursing Considerations: Pre- and post-procedure care, monitoring for bleeding at access site, neurovascular checks of affected limb, pain management, and signs of reperfusion injury.

- A small, retrievable filter is placed in the inferior vena cava (the large vein returning blood from the lower body to the heart) to catch blood clots traveling from the legs before they reach the lungs.

- Used in patients with DVT who cannot take anticoagulants (due to high bleeding risk) or when anticoagulants fail.

- Nursing Considerations: Monitor for complications related to insertion (e.g., bleeding, infection, filter migration, IVC perforation) and long-term complications (e.g., filter fracture, recurrent DVT above the filter).

- For DVT, graduated compression stockings are often used to reduce swelling and pain, and to help prevent post-thrombotic syndrome.

- Nursing Considerations: Proper fitting and patient education on application and wearing schedule.

- Early Ambulation: As soon as medically safe, to promote blood flow and prevent stasis.

- Hydration: To prevent increased blood viscosity.

- Smoking Cessation: Reduces endothelial damage and hypercoagulability.

- Weight Management: Reduces overall cardiovascular risk.

- Regular Exercise: Improves circulation.

- Control of Underlying Conditions: Effective management of hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and atrial fibrillation.

EMBOLUS

Definition

An embolus (plural: emboli) refers to any foreign material, such as a blood clot, fatty deposit, air bubble, or other debris, that travels through the bloodstream from one part of the body and lodges in a blood vessel, causing an obstruction. While most emboli are detached fragments of thrombi (thromboemboli), they can also originate from other substances.

Pathophysiology of Embolism

An embolus becomes clinically significant when it lodges in a blood vessel that is too narrow for it to pass through, thereby blocking blood flow to the downstream tissues or organs. This obstruction leads to a condition called embolism. The consequences of an embolism depend on the size of the embolus, the location of the occlusion, and the collateral blood supply to the affected area.

When blood flow is cut off, the affected tissue experiences ischemia (lack of oxygen and nutrients). If the blood supply is not restored promptly, the cells in that tissue will begin to die, leading to infarction. The clinical presentation of an embolism is often sudden and severe, reflecting the acute deprivation of blood supply.

Types of Embolism

Embolism can be classified based on the composition of the embolus and its origin/destination:

1. Thromboembolism:- The most common type of embolism. It occurs when a piece of a thrombus (blood clot) breaks off from its original site of formation and travels through the bloodstream.

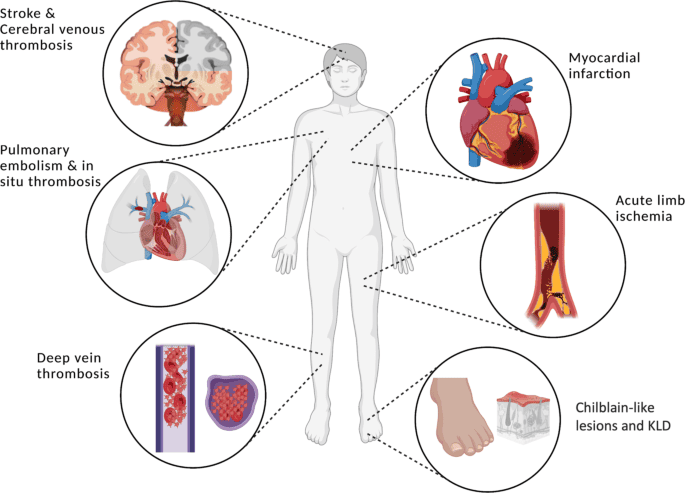

- Pulmonary Embolism (PE): A life-threatening condition where a piece of a thrombus, typically originating from a Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT) in the legs or pelvis, travels through the right side of the heart and lodges in the pulmonary arteries of the lungs. This blocks blood flow to a portion of the lung, impairing gas exchange.

- Systemic Arterial Embolism: An embolus (often originating from a cardiac thrombus due to atrial fibrillation, myocardial infarction, or valvular disease, or from an atherosclerotic plaque in the aorta) travels through the arterial system and lodges in an artery supplying an organ or limb. This can lead to:

- Cerebral Embolism: When an embolus lodges in a blood vessel in the brain, causing an ischemic stroke.

- Peripheral Arterial Embolism: Affecting arteries in the limbs (e.g., legs, arms), causing acute limb ischemia.

- Mesenteric Embolism: Affecting arteries supplying the intestines, leading to intestinal ischemia/infarction.

- Renal Embolism: Affecting arteries supplying the kidneys, potentially causing kidney injury or infarction.

- Splenic Embolism: Affecting arteries supplying the spleen, potentially causing splenic infarction.

- Retinal Embolism: An embolus lodges in an artery of the retina, causing sudden vision loss (amaurosis fugax or permanent vision loss).

- Paradoxical Embolism: A rare type where a venous thrombus crosses from the right side of the heart to the left side through a patent foramen ovale (PFO) or atrial septal defect (ASD) and then enters the systemic circulation, causing an arterial embolism (e.g., stroke).

- Occurs when fat globules enter the circulation and lodge in small blood vessels, most commonly in the lungs, brain, or skin.

- Often seen after long bone fractures (e.g., femur, tibia), orthopedic surgery (e.g., joint replacement), severe burns, or pancreatitis.

- Can lead to Fat Embolism Syndrome (FES), a constellation of symptoms including respiratory distress, neurological dysfunction, and petechial rash.

- Occurs when air bubbles enter the circulation and obstruct blood flow.

- Can result from improper insertion or removal of central venous catheters, surgical procedures (especially neurosurgery, cardiac surgery), chest trauma, lung biopsy, or diving accidents (decompression sickness).

- Can be venous (traveling to the heart and lungs, causing pulmonary obstruction) or arterial (if air crosses to the left side of the heart, causing stroke or myocardial ischemia).

- A piece of infected material (containing bacteria, fungi, or other pathogens) breaks off from a site of infection (e.g., infective endocarditis, abscesses) and travels through the bloodstream.

- Can lodge in various organs, causing new sites of infection, abscess formation, or infarction (e.g., septic pulmonary emboli in intravenous drug users with tricuspid endocarditis, septic arterial emboli causing brain abscesses).

- A rare but catastrophic obstetric emergency where amniotic fluid, fetal cells, hair, or other debris enters the mother's bloodstream, typically during labor, delivery, or immediately postpartum.

- Triggers a severe inflammatory and coagulopathic reaction, leading to acute respiratory distress, cardiovascular collapse, and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC).

- Occurs when malignant cancer cells or fragments of a tumor break off from the primary site and enter the bloodstream or lymphatic system.

- These tumor emboli can then travel to distant sites and establish new tumors (metastasis).

- Rare, caused by accidental introduction of non-biological material into the bloodstream.

- Examples include catheter fragments, talc (in intravenous drug users), or bullet fragments.

Similarities and Differences Between Thrombus and Embolus

Similarities

While often used interchangeably in casual conversation, thrombus and embolus are distinct but related concepts in cardiovascular pathology. Their similarities highlight their shared role in obstructing blood flow:

- Both refer to blood clots or related occlusive masses: At their core, both terms describe a solid or semi-solid mass within the circulatory system. Although an embolus can be non-thrombotic (e.g., fat, air), the most common type of embolus is a thromboembolus.

- Both occur inside the circulatory system: Neither thrombi nor emboli are typically found outside blood vessels or the heart chambers.

- Both can be made up of various components: While thrombi are primarily composed of platelets, fibrin, and blood cells, emboli can also be formed from fat, air, amniotic fluid, tumor cells, infectious material, or foreign substances.

- Both can block the lumen of blood vessels: This is their primary pathological consequence – they physically obstruct the flow of blood, leading to ischemia and potential tissue damage.

- Both can lead to serious clinical complications: Both conditions can result in life-threatening events such as myocardial infarction, stroke, pulmonary embolism, and organ damage.

- Both are influenced by Virchow's Triad (indirectly for embolus): While Virchow's Triad directly explains thrombus formation, the embolus often originates from a thrombus, thus indirectly linking its formation to the principles of endothelial injury, stasis, and hypercoagulability.

Comparison Table

| No. | Variable | Thrombus | Embolus |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Definition | A blood clot (solid mass of blood constituents) formed and remaining attached to the wall of a blood vessel or heart chamber at its site of origin. | Any intravascular mass (most commonly a piece of a thrombus) that travels through the bloodstream from one site and lodges in a blood vessel at a distant site, causing occlusion. |

| 2. | Mobility / State | Stationary; attached to the vessel wall. It is a localized phenomenon. | Mobile; freely floating in the bloodstream until it lodges. It is a migratory phenomenon. |

| 3. | Location of Obstruction | Obstructs blood flow at its site of formation. | Obstructs blood flow at a site distant from its origin, typically where the vessel narrows or bifurcates. |

| 4. | Origin | Forms de novo within a blood vessel or heart chamber due to local factors (Virchow's Triad). | Over 90% originate from a pre-existing thrombus (thromboembolus). Other origins include fat, air, amniotic fluid, tumor cells, bacteria, or foreign bodies. |

| 5. | Primary Composition | Primarily blood components: fibrin, platelets, red blood cells, white blood cells. | Predominantly thrombotic material, but can also be non-thrombotic (e.g., fat, air, tumor, bacteria, amniotic fluid). |

| 6. | Clinical Presentation | Symptoms may be gradual or acute, depending on the degree and rate of obstruction at the site of formation (e.g., stable angina from coronary thrombus, DVT symptoms). | Typically causes acute, sudden onset of symptoms due to abrupt occlusion of a distant vessel (e.g., sudden dyspnea in PE, sudden neurological deficit in stroke). |

| 7. | Examples | Arterial thrombus (e.g., in coronary artery causing MI), Venous thrombus (e.g., Deep Vein Thrombosis - DVT), Cardiac mural thrombus. | Pulmonary Embolism (PE), Ischemic Stroke (cerebral embolism), Peripheral Arterial Embolism, Fat Embolism, Air Embolism. |

Clinical Manifestations of Embolism

The signs and symptoms of an embolism are highly dependent on the location where the embolus lodges and the extent of blood flow obstruction. Symptoms typically have a sudden onset.

- Pulmonary Embolism (PE):

- Sudden onset of shortness of breath (dyspnea).

- Pleuritic chest pain (sharp, stabbing pain that worsens with deep breathing or coughing).

- Tachypnea (rapid breathing) and Tachycardia (rapid heart rate).

- Cough, sometimes with bloody sputum (hemoptysis).

- Anxiety, restlessness, feeling of impending doom.

- Dizziness or lightheadedness, syncope (fainting).

- Signs of right heart strain in massive PE (e.g., jugular venous distension, hypotension, shock).

- Cerebral Embolism (Ischemic Stroke):

- Sudden weakness or numbness, typically affecting one side of the body (face, arm, leg).

- Sudden difficulty speaking (dysarthria) or understanding speech (aphasia).

- Sudden vision changes in one or both eyes.

- Sudden severe headache with no known cause.

- Sudden dizziness, loss of balance, or coordination.

- Peripheral Arterial Embolism:

- Sudden, severe pain in the affected limb.

- Pallor (paleness) of the limb.

- Pulselessness below the occlusion.

- Paresthesia (numbness or tingling).

- Paralysis (in severe cases, inability to move the limb).

- Poikilothermia (coldness) of the affected limb.

- (The classic "6 Ps": Pain, Pallor, Pulselessness, Paresthesia, Paralysis, Poikilothermia).

- Mesenteric Embolism:

- Severe, sudden abdominal pain, often disproportionate to physical findings (e.g., abdomen may not be very tender initially).

- Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea.

- Bloody stools (later stage as bowel infarction develops).

- Abdominal distension.

- Retinal Embolism:

- Sudden, painless loss of vision in one eye, often described as a "curtain" coming down or complete darkness.

- Temporary vision loss (amaurosis fugax) if the embolus passes.

- Fat Embolism Syndrome (FES):

- Onset 12-72 hours after initial injury.

- Respiratory distress: Dyspnea, tachypnea, hypoxemia, diffuse pulmonary infiltrates on chest X-ray.

- Neurological dysfunction: Confusion, agitation, stupor, seizures, coma.

- Petechial rash: Small, non-blanching red spots typically on the upper torso, neck, axillae, and conjunctiva.

- Fever, tachycardia.

- Air Embolism:

- Symptoms depend on volume and location:

- Venous Air Embolism: Sudden dyspnea, chest pain, hypotension, cyanosis, "millwheel murmur" (churning sound heard over the precordium).

- Arterial Air Embolism: Neurological deficits (similar to stroke), myocardial ischemia/infarction symptoms, visual disturbances.

- Symptoms depend on volume and location:

- Septic Embolism:

- Signs of systemic infection (fever, chills, malaise).

- Symptoms related to the organ where the embolus lodges (e.g., respiratory symptoms for septic PE, neurological symptoms for brain abscess).

Diagnosis of an Embolism

Diagnosis of an embolism relies on a combination of clinical suspicion, risk factor assessment, specific blood tests, and advanced imaging studies tailored to the suspected location.

- Clinical Assessment:

- Thorough patient history, including recent surgeries, trauma, prolonged immobility, cardiac conditions (e.g., atrial fibrillation), cancer, and family history of clotting disorders.

- Physical examination: Vital signs, lung sounds, heart sounds, neurological exam, vascular exam (pulses, color, temperature of limbs), assessment for DVT signs if PE is suspected.

- Blood Tests:

- D-dimer: Useful for ruling out DVT/PE in low-risk patients. A normal D-dimer makes PE/DVT very unlikely. An elevated D-dimer is non-specific and requires further investigation.

- Arterial Blood Gas (ABG): To assess oxygenation and acid-base status, particularly in PE.

- Cardiac Biomarkers (Troponin, BNP): May be elevated in PE due to right heart strain or in myocardial infarction.

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) and Inflammatory Markers (ESR, CRP): May indicate infection or inflammation.

- Coagulation studies (PT/INR, aPTT): To assess baseline clotting status and guide/monitor anticoagulant therapy.

- Blood Cultures: If septic embolism is suspected.

- Imaging Studies:

- For Pulmonary Embolism (PE):

- CT Pulmonary Angiogram (CTPA): The gold standard. A CT scan with intravenous contrast that visualizes the pulmonary arteries to detect emboli.

- Ventilation-Perfusion (V/Q) Scan: Used when CTPA is contraindicated (e.g., renal insufficiency, contrast allergy), assesses airflow and blood flow in the lungs.

- Lower Extremity Duplex Ultrasound: To confirm the presence of DVT, which is the source of most PEs.

- Echocardiography: May show signs of right heart strain or identify a cardiac source of emboli (e.g., thrombus in right atrium/ventricle, PFO).

- For Cerebral Embolism (Stroke):

- Non-contrast CT Head: Initial scan to rule out hemorrhagic stroke.

- CT Angiography (CTA) or MR Angiography (MRA) of head and neck: To visualize cerebral blood vessels and identify occlusions.

- Carotid Duplex Ultrasound: To assess for carotid artery stenosis as a potential source of emboli.

- Echocardiography (Transthoracic or Transesophageal): To identify cardiac sources of emboli (e.g., atrial fibrillation, valvular disease, PFO).

- For Peripheral Arterial Embolism:

- Duplex Ultrasound: To visualize arterial flow and identify the occlusion.

- CT Angiography (CTA) or MR Angiography (MRA) of the affected limb: Provides detailed anatomical information.

- Conventional Angiography: Invasive, but can provide high-resolution images and allow for immediate intervention.

- For Fat Embolism Syndrome: Diagnosis is primarily clinical, based on the classic triad (respiratory distress, neurological symptoms, petechial rash). Imaging (chest X-ray, CT chest) may show diffuse pulmonary infiltrates.

- For Air Embolism: Clinical suspicion is key. Imaging may show air in vascular structures (e.g., CT, echocardiography).

- For Pulmonary Embolism (PE):

Treatment of an Embolism

The treatment of an embolism is an urgent medical emergency aimed at restoring blood flow, preventing further embolization, and managing symptoms. The specific approach varies greatly depending on the type, location, and severity of the embolism.

- Anticoagulation:

- The cornerstone of treatment for most thromboembolism (e.g., PE, DVT, some strokes) to prevent the existing clot from growing and to prevent new clots from forming.

- Medications: Heparin (unfractionated or LMWH) for initial rapid anticoagulation, followed by oral anticoagulants (Warfarin or DOACs) for long-term therapy.

- Nursing Considerations: Close monitoring for bleeding, regular lab checks (aPTT, PT/INR), patient education on medication adherence and bleeding precautions.

- Thrombolysis (Fibrinolysis):

- "Clot-busting" medications (e.g., alteplase, tenecteplase) that actively dissolve the clot.

- Used in severe, life-threatening cases where rapid clot dissolution is crucial (e.g., massive PE with hemodynamic instability, acute ischemic stroke within a specific time window, severe acute limb ischemia).

- Can be administered systemically (intravenously) or directly into the clot via a catheter (catheter-directed thrombolysis).

- Nursing Considerations: High risk of serious bleeding. Intensive monitoring for hemorrhage, neurological changes (for stroke), and strict adherence to protocols.

- Embolectomy (Surgical or Catheter-Based):

- Physical removal of the embolus.

- Surgical Embolectomy: Open surgical procedure to remove the clot, often used for large arterial emboli causing limb ischemia or massive PE unresponsive to thrombolysis.

- Catheter-Based Embolectomy: Minimally invasive procedure where a catheter is threaded to the clot, and the embolus is aspirated, fragmented, or removed using specialized devices. Used for PE, stroke, and peripheral emboli.

- Nursing Considerations: Pre- and post-procedure care, monitoring for bleeding at access sites, neurovascular checks of affected limb, pain management, and close monitoring of vital signs.

- Supportive Care:

- Oxygen Therapy: To improve oxygenation, especially in PE or severe stroke.

- Pain Management: To alleviate discomfort.

- Hemodynamic Support: Vasopressors and fluids for hypotension in severe PE or shock.

- Respiratory Support: Mechanical ventilation if respiratory failure occurs (e.g., in severe PE, Fat Embolism Syndrome).

- Symptom-Specific Management: For cerebral embolism, may include blood pressure control, glucose management, and fever reduction.

- Inferior Vena Cava (IVC) Filters:

- A small, retrievable filter placed in the IVC to catch clots traveling from the legs to the lungs.

- Used in patients with DVT who have contraindications to anticoagulation or who experience recurrent PE despite adequate anticoagulation.

- Nursing Considerations: Monitor for insertion site complications, filter migration, and long-term complications.

- Specific Treatments for Non-Thromboembolic Embolisms:

- Fat Embolism Syndrome: Primarily supportive care, including oxygenation, ventilation, and hemodynamic support.

- Air Embolism: Positioning the patient in a left lateral Trendelenburg position (Durant's maneuver) to trap air in the right ventricle, oxygen administration, and hyperbaric oxygen therapy for arterial air embolism.

- Septic Embolism: Aggressive antibiotic therapy for the underlying infection, and potentially drainage of abscesses.

- Amniotic Fluid Embolism: Immediate supportive care including respiratory and cardiovascular support, blood product transfusion for DIC, and uterine management.

- Prevention of Recurrence:

- Long-term anticoagulation for thromboembolism.

- Management of underlying risk factors (e.g., atrial fibrillation, atherosclerosis).

- Lifestyle modifications (smoking cessation, weight management, regular exercise).

Nursing Diagnoses and Interventions for Thromboembolic Disorders

Nursing diagnoses provide a framework for nursing care, identifying patient problems that nurses can independently address. Below are common nursing diagnoses related to thromboembolic disorders, each with associated interventions.

1. Ineffective Tissue Perfusion (Specify type: Pulmonary, Cerebral, Peripheral)

Definition: Decrease in oxygen resulting in failure to nourish the tissues at the capillary level.

Related to:

- Interruption of arterial/venous blood flow by clot formation (thrombus or embolus).

- Compromised oxygen transport due to ventilation-perfusion mismatch (in PE).

- Increased vascular resistance.

Assessment Cues:

- Pulmonary: Dyspnea, tachypnea, chest pain, hypoxemia, apprehension, decreased breath sounds.

- Cerebral: Altered mental status, motor/sensory deficits, speech disturbances, vision changes.

- Peripheral: Pain, pallor, pulselessness, paresthesia, paralysis, poikilothermia (coldness), swelling, diminished pulses.

Nursing Interventions:

- Monitor Vital Signs: Assess respiratory rate, heart rate, blood pressure, and oxygen saturation frequently. Note any changes suggestive of worsening perfusion (e.g., increased respiratory rate, decreased SpO2, hypotension).

- Administer Oxygen Therapy: As prescribed, to maintain optimal oxygen saturation, especially in pulmonary embolism.

- Position Patient: For PE, elevate the head of the bed to a semi-Fowler's or high-Fowler's position to facilitate lung expansion. For DVT, elevate the affected extremity to promote venous return and reduce edema.

- Assess Affected Area:

- Pulmonary: Auscultate lung sounds, monitor respiratory effort and depth.

- Cerebral: Perform frequent neurological assessments (e.g., Glasgow Coma Scale, motor/sensory function, pupillary response).

- Peripheral: Assess pulses (dorsalis pedis, posterior tibial, radial, etc.), skin color, temperature, capillary refill, sensation, and motor function of the affected limb. Measure limb circumference as indicated.

- Administer Anticoagulants/Thrombolytics: As prescribed, carefully monitoring for therapeutic effects and potential complications (e.g., bleeding).

- Maintain Hydration: Administer IV fluids as ordered to maintain adequate circulating volume, unless contraindicated.

- Prepare for Procedures: Assist with preparation for diagnostic tests (e.g., CT angiogram, Doppler ultrasound) or interventional procedures (e.g., embolectomy, IVC filter placement).

2. Acute Pain

Definition: Unpleasant sensory and emotional experience arising from actual or potential tissue damage, with sudden or slow onset of any intensity from mild to severe with an anticipated or predictable end.

Related to:

- Tissue ischemia/infarction.

- Inflammation secondary to vascular occlusion.

- Pleuritic irritation (in PE).

- Surgical incision/procedure (if applicable).

Assessment Cues:

- Verbal reports of pain (e.g., chest pain, calf pain, abdominal pain).

- Non-verbal cues (e.g., grimacing, guarding, restlessness, moaning).

- Increased heart rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure.

- Facial pallor.

Nursing Interventions:

- Assess Pain: Use a standardized pain scale (e.g., 0-10) to assess pain intensity, location, quality, and aggravating/alleviating factors. Assess frequently.

- Administer Analgesics: As prescribed, promptly and evaluate effectiveness.

- Provide Non-Pharmacological Comfort Measures:

- Repositioning for comfort.

- Application of warm/cold compresses (use caution with anticoagulants and impaired circulation).

- Distraction techniques (e.g., guided imagery, music).

- Quiet environment and adequate rest.

- Elevate Affected Limb: For DVT, elevation helps reduce swelling and discomfort.

- Educate Patient: About pain management strategies and to report unrelieved pain.

3. Risk for Bleeding

Definition: Susceptible to a decrease in blood volume that may compromise health.

Related to:

- Administration of anticoagulants (heparin, warfarin, DOACs) or thrombolytics.

- Disruption of clotting factors.

- Invasive procedures or trauma.

Assessment Cues:

- Active bleeding (e.g., epistaxis, hematuria, melena, hematemesis, gingival bleeding).

- Bruising, petechiae, purpura.

- Changes in vital signs (e.g., tachycardia, hypotension) indicative of hypovolemia.

- Decreased hemoglobin/hematocrit.

- Prolonged PT/INR or aPTT.

- Altered mental status (suggesting intracranial bleed).

Nursing Interventions:

- Monitor Coagulation Studies: Regularly check PT/INR for warfarin, aPTT for heparin, and monitor complete blood count (CBC) for hemoglobin and hematocrit.

- Assess for Signs of Bleeding: Inspect skin, urine, stool, emesis, and any drainage for blood. Monitor for epistaxis, gingival bleeding, and signs of internal bleeding (e.g., abdominal distension, headache, altered mental status).

- Implement Bleeding Precautions:

- Avoid intramuscular injections.

- Use smallest gauge needles for venipuncture.

- Apply prolonged pressure to venipuncture sites.

- Avoid vigorous toothbrushing; use a soft-bristle toothbrush.

- Use an electric razor instead of a blade.

- Avoid rectal temperatures, suppositories, and enemas.

- Caution patient against vigorous nose blowing, coughing, or straining.

- Prevent falls and injury.

- Administer Antidotes: Be prepared to administer antidotes (e.g., protamine sulfate for heparin, vitamin K for warfarin) as ordered in case of severe bleeding or overdose.

- Educate Patient: On signs of bleeding to report immediately, importance of medication adherence, and avoiding over-the-counter medications that can increase bleeding risk (e.g., NSAIDs, aspirin, herbal supplements).

4. Impaired Physical Mobility

Definition: Limitation in independent, purposeful physical movement of the body or one or more extremities.

Related to:

- Pain and discomfort.

- Activity restrictions (e.g., bed rest for DVT, post-stroke deficits).

- Neuromuscular impairment (in cerebral embolism).

- Fatigue.

Assessment Cues:

- Reluctance to move.

- Limited range of motion.

- Decreased muscle strength.

- Difficulty with gait or balance.

- Pain with movement.

Nursing Interventions:

- Encourage Mobility within Restrictions: Assist with range of motion exercises (active or passive) to prevent joint stiffness and muscle atrophy, as tolerated and not contraindicated.

- Assist with Ambulation: As appropriate and safe, using assistive devices if needed. Gradual increase in activity is key for DVT/PE patients once stable and on anticoagulation.

- Position for Comfort and Function: Reposition patient frequently if on bed rest to prevent pressure injuries and promote circulation. Use pillows or wedges to support extremities.

- Collaborate with PT/OT: Consult physical therapy (PT) and occupational therapy (OT) for specialized exercises, gait training, and adaptive equipment.

- Educate Patient: On the importance of mobility, prescribed activity levels, and techniques to prevent complications of immobility.

5. Deficient Knowledge (about condition, treatment, prevention)

Definition: Absence or deficiency of cognitive information related to specific topic.

Related to:

- Lack of exposure/recall.

- Information misinterpretation.

- Unfamiliarity with information resources.

Assessment Cues:

- Questions about the disease process, medications, lifestyle changes.

- Inaccurate statements about condition or treatment.

- Lack of follow-through with instructions.

Nursing Interventions:

- Assess Learning Needs: Determine the patient's current knowledge level, preferred learning style, and readiness to learn.

- Provide Education:

- Disease Process: Explain what a thrombus/embolus is, its causes, and potential complications in clear, simple terms.

- Medication Management: Explain the purpose, dose, schedule, side effects of anticoagulants, importance of strict adherence, and the need for regular lab monitoring (e.g., INR for warfarin).

- Bleeding Precautions: Reinforce all bleeding precautions and signs to report.

- Lifestyle Modifications: Discuss smoking cessation, healthy diet, regular exercise (as able), weight management.

- Prevention of Recurrence: Emphasize avoiding prolonged sitting/standing, performing leg exercises during travel, adequate hydration, and wearing compression stockings (if prescribed).

- Follow-up Care: Importance of follow-up appointments and continued monitoring.

- Signs/Symptoms to Report: Educate on when to seek immediate medical attention (e.g., sudden shortness of breath, chest pain, signs of bleeding, neurological changes).

- Use Various Teaching Methods: Provide written materials, visual aids, and utilize teach-back method to ensure understanding.

- Involve Family/Caregivers: Educate significant others as appropriate to support the patient's care.

- Provide Resources: Refer to support groups or reliable online resources.