Table of Contents

ToggleHAEMORRHAGE: Nursing Lecture Notes

Haemorrhage, commonly known as bleeding, is the loss of blood from the circulatory system, specifically from blood vessels. It is a critical medical condition that, if uncontrolled, can lead to severe physiological compromise and death. The body possesses intrinsic defence mechanisms, primarily through the process of clotting (hemostasis), to prevent excessive blood leakage. However, these mechanisms can be deficient due to underlying diseases, absence of essential clotting factors, or the use of anticoagulant medications.

Types of Haemorrhage

Haemorrhage is classified based on several key characteristics to aid in diagnosis, prognosis, and management. These classifications include:

- The type of blood vessel involved.

- The location or situation of the haemorrhage.

- The time of occurrence or duration of the haemorrhage.

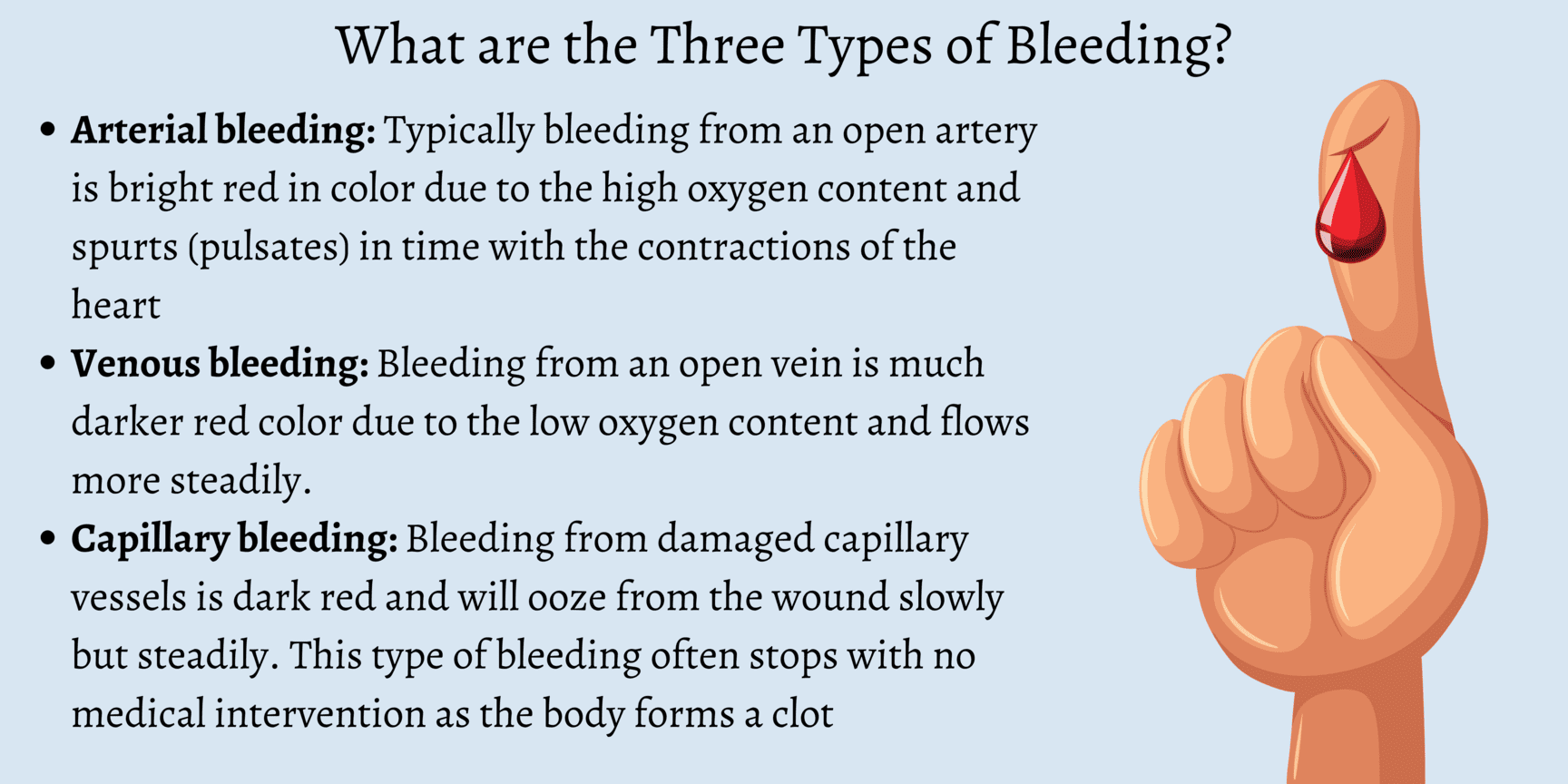

Classification by Blood Vessels Involved

The characteristics of bleeding often provide clues as to which type of blood vessel has been compromised:

1. Arterial Haemorrhage:Classification by Time or Duration of Haemorrhage

The timing of haemorrhage relative to an injury or surgical procedure provides important diagnostic and prognostic information:

1. Primary Haemorrhage:- Increased intravascular pressure due to actions such as coughing or vomiting.

- Increased venous pressure.

- Physical excitement or administration of stimulant drugs.

- Sepsis: Bacterial infection leading to inflammation and enzymatic destruction of vessel walls.

- Enzymatic Action: For example, the action of pepsin on a bleeding peptic ulcer, eroding the vessel.

- Mechanical Pressure: Persistent pressure from a drainage tube or foreign body (e.g., bone fragment) eroding a vessel.

- Presence of Carcinoma: Malignant tumors can erode blood vessels, leading to chronic or acute bleeding.

Classification by Situation or Location of Haemorrhage

This classification distinguishes whether the blood loss is visible externally or contained within body cavities:

1. External or Revealed Haemorrhage:- Definition: This is bleeding that is directly visible, either from an open wound on the body surface or from a natural body orifice (e.g., epistaxis from the nose, hematemesis from vomiting blood, melena/hematochezia from the rectum).

- Visibility: Blood is immediately apparent and can be quantified relatively easily.

- Definition: This refers to bleeding that occurs into an internal body cavity or tissue space, where the blood loss is not immediately visible externally.

- Locations: Common sites include the peritoneal cavity (e.g., ruptured spleen), pleural cavity (e.g., hemothorax), retroperitoneal space, lumen of hollow organs (e.g., intestines, stomach, bladder), or within the tissues of a limb (e.g., large hematoma).

- Diagnosis: Since the bleeding is concealed, diagnosis relies heavily on the patient's symptoms and signs of hypovolemia and shock. It may be "revealed" later if the blood exits the body (e.g., vomited blood, blood passed per rectum) or by the formation of bruising and swelling on the surface of the body.

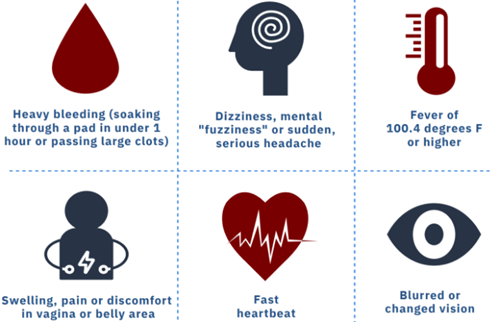

Clinical Picture: Signs and Symptoms of Haemorrhage

The clinical presentation of haemorrhage varies depending on the amount, rate, and duration of blood loss. Symptoms and signs reflect the body's compensatory mechanisms attempting to maintain vital organ perfusion, followed by the failure of these mechanisms as blood loss becomes severe. The progression is often categorized into stages of shock.

Early Symptoms and Signs (Compensatory Stage / Class I & II Haemorrhage)

These signs indicate the body's initial attempts to compensate for blood loss (up to 15-30% of blood volume). The sympathetic nervous system is activated.

Neurological/Mental Status:- Restlessness and Anxiety: Often one of the earliest signs, resulting from cerebral hypoperfusion and increased catecholamine release.

- Increased Thirst: Due to fluid shifts and activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system.

- Slightly Increased Pulse Rate (Mild Tachycardia): The heart beats faster to maintain cardiac output despite reduced blood volume.

- Blood Pressure (BP) Maintained or Slightly Lowered: Due to peripheral vasoconstriction attempting to shunt blood to vital organs. Orthostatic hypotension may be present.

- Pallor (Paleness): Due to vasoconstriction and reduced blood flow to the skin.

- Coldness: Skin feels cool to the touch (subnormal temperature, e.g., 36.9°C), also due to peripheral vasoconstriction.

- Slightly Clammy Skin: Due to increased sweating from sympathetic activation.

- Oliguria (Reduced Urine Output): The kidneys conserve fluid and blood flow is shunted away from them.

Symptoms and Signs of Severe Haemorrhage (Decompensatory & Irreversible Stages / Class III & IV Haemorrhage)

These signs manifest when compensatory mechanisms are overwhelmed, and blood loss exceeds 30-40% of total blood volume. This leads to profound organ hypoperfusion and cellular dysfunction.

Neurological/Mental Status:- Lethargy, Drowsiness, Confusion: Progressive worsening of cerebral hypoperfusion.

- Decreased Responsiveness: Leading to stupor and eventually coma.

- Blindness, Tinnitus (Buzzing in the Ears): Severe cerebral ischemia.

- Extreme Pallor: Face becomes ashen white, indicating severe cutaneous vasoconstriction and lack of circulating blood.

- Profound Coldness: Core body temperature may drop significantly (e.g., 36°C or lower), indicating severe hypothermia and circulatory collapse.

- Pulse: Very rapid in rate (severe tachycardia, >120 bpm), thready in volume (barely palpable), and often irregular in rhythm, indicating a severely compromised cardiac output.

- Blood Pressure: Extremely low (severe hypotension), indicating failed compensation and impending circulatory collapse.

- Low Venous Pressure: Due to severely depleted intravascular volume.

- Air Hunger: The patient gasps for breath, with respirations becoming rapid and sighing (Kussmaul-like breathing), as the body attempts to compensate for metabolic acidosis resulting from anaerobic metabolism.

- Dyspnea: Difficult or labored breathing.

- Diminished Urine Volume: Progressing to anuria (no urine production), which may result in acute renal failure due to prolonged renal ischemia.

- Extreme Thirst: Persists and worsens.

- Metabolic Acidosis: Due to widespread anaerobic metabolism and lactic acid accumulation.

- Eventual Multi-Organ Dysfunction Syndrome (MODS): Leading to irreversible organ damage and death.

Management of Haemorrhage: Principles of Care

Effective management of haemorrhage is time-sensitive and aims to stop the bleeding, restore circulating blood volume, optimize tissue perfusion, and treat any underlying coagulopathy.

Immediate Priorities (The "ABCDE" Approach):

- Airway: Ensure a patent airway. If the patient's consciousness is compromised, intubation may be necessary to protect the airway and facilitate ventilation.

- Breathing: Assess respiratory effort and oxygenation. Administer high-flow oxygen (e.g., via non-rebreather mask) to maximize oxygen delivery to tissues. Provide ventilatory support if needed.

- Circulation: This is paramount in haemorrhage.

- Direct Pressure: Apply direct pressure to any visible external bleeding site.

- Large-Bore IV Access: Establish at least two large-bore intravenous (IV) lines for rapid fluid and blood product administration.

- Fluid Resuscitation: Begin rapid infusion of crystalloid solutions (e.g., 0.9% Normal Saline, Lactated Ringer's) while awaiting blood products.

- Blood Transfusion: Initiate blood product transfusion (e.g., packed red blood cells, fresh frozen plasma, platelets) as soon as possible, especially for significant haemorrhage. Consider massive transfusion protocols if appropriate.

- Identify and Stop Bleeding: Promptly identify the source of bleeding and take definitive steps to control it (e.g., surgical intervention, endoscopic intervention, interventional radiology embolization, tourniquet for severe limb trauma).

- Disability (Neurological Status): Assess the patient's level of consciousness (e.g., AVPU scale, GCS) to monitor cerebral perfusion.

- Exposure and Environment: Fully expose the patient to identify all injuries and bleeding sites. Prevent hypothermia by covering the patient with warm blankets, as hypothermia exacerbates coagulopathy.

Ongoing Management and Monitoring:

- Continuous Monitoring: Continuously monitor vital signs (heart rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation), ECG, and urine output. An arterial line may be used for continuous blood pressure monitoring.

- Laboratory Monitoring: Serial blood tests, including complete blood count (CBC), electrolytes, coagulation profile (PT, PTT, fibrinogen), blood type and cross-match, and lactate levels (to assess tissue perfusion and acidosis).

- Temperature Control: Maintain normothermia; hypothermia can worsen coagulopathy and acidosis.

- Correct Coagulopathy: Administer specific clotting factors, cryoprecipitate, or prothrombin complex concentrates (PCCs) as indicated, especially if the patient is on anticoagulants or has a pre-existing coagulopathy. Consider tranexamic acid (TXA) as an antifibrinolytic.

- Pain Management: Administer analgesia cautiously, considering its potential effects on blood pressure and mental status.

- Prevent Complications: Implement strategies to prevent acute kidney injury, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), and multi-organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS).

- Definitive Treatment: Address the underlying cause of the haemorrhage once the patient is stabilized.

Management and Interventions

Effective management of haemorrhage is time-sensitive and requires a multi-faceted approach. The primary goals are to:

- Arrest the haemorrhage: Control and stop the bleeding at its source.

- Restore blood volume: Replenish lost blood and fluids to maintain adequate circulation.

- Manage the extravasated blood: Address the consequences of blood accumulating outside the vessels, and support the body's physiological responses.

I. Arrest of Haemorrhage: Controlling the Bleeding Source

The methods to control bleeding depend on whether the haemorrhage is revealed (external) or concealed (internal).

A. Arrest of Revealed (External) Haemorrhage

Most forms of external haemorrhage can be controlled by applying pressure directly or indirectly to the bleeding site. The choice of method depends on the severity and nature of the bleeding:

Direct Pressure (Pad & Bandage):- Method: This is the simplest, most effective, and often the first line of treatment. Apply a clean, sterile pad directly to the bleeding wound and secure it firmly with a bandage.

- Mechanism: Direct pressure compresses the bleeding vessels, allowing clots to form.

- Advantages: Highly effective, causes minimal damage, and can be performed quickly.

- Method: Fingers are used to apply firm pressure over the pressure point of an artery that supplies the wounded area, proximal to the injury.

- Mechanism: Temporarily occludes the main arterial blood supply to the limb or area.

- Application: Commonly used in areas where direct pressure might be difficult or less effective, such as on the neck (e.g., carotid artery pressure point in severe facial bleeding). It provides temporary control until definitive measures can be taken.

- Method: Raising the injured limb above the level of the heart.

- Mechanism: Reduces hydrostatic pressure in the veins, which can help control venous bleeding.

- Application: A classical method for controlling bleeding from ruptured varicose veins of the leg or other venous injuries.

- Method: A constricting band applied proximally to an injury on a limb. Tourniquets include devices like the Samway anchor, Esmarch’s Elastic bandage, or inflatable cuffs.

- Application: **Use ONLY for the control of heavy, life-threatening bleeding from a limb when other methods have failed or are not feasible.**

- Dangers: If left on for more than 30 minutes, it carries significant risks such as gangrene, nerve damage, and reperfusion injury upon removal. Requires careful application and monitoring.

- Method: Surgically tying off the bleeding vessel with sutures.

- Application: Necessary if bleeding continues despite less invasive measures or for larger vessels.

- Method: Application of heat (via electrical current) to the bleeding point to seal small vessels.

- Application: Commonly used in surgical settings for precise haemostasis.

- Method: Deliberate occlusion of bleeding blood vessels by introducing embolic materials (e.g., coils, particles, glues) through an angiographic catheter under imaging guidance.

- Application: Common in controlling bleeding from internal sources like oesophageal varices, gastric ulcers, or arterial bleeds in inaccessible locations. Examples of emboli include lyophilized human dura mater.

- Method: Insertion of sterile gauze or specialized hemostatic dressings into a wound or cavity to apply internal pressure.

- Application: A temporary measure for very severe bleeding, often used in theatre to control sudden haemorrhage or for diffuse bleeding that is difficult to ligate.

- Method: Substances capable of causing bleeding to stop when applied locally.

- Examples: Include topical thrombin, collagen, gelatin sponges, oxidized regenerated cellulose (Oxycel). Some natural substances like snake venom or adrenaline can also act as styptics.

- Application: Used locally in certain cases for low-pressure bleeding from capillaries and venules.

B. Arrest of Concealed (Internal) Haemorrhage

Controlling internal haemorrhage is more challenging as direct pressure is often not possible. Management focuses on internal pressure, addressing the underlying cause, and enhancing coagulation.

Surgical Ligation/Repair:- Method: Direct surgical intervention to identify and ligate or repair the bleeding vessel.

- Application: Often the definitive treatment for ruptured organs (e.g., ruptured spleen, liver laceration) or major vessel injuries.

- Method: Removing blood clots from a hollow organ can allow it to contract and seal bleeding vessels.

- Application: For severe bleeding from the bladder, passing a catheter and emptying it of clots can help the bladder contract and tamponade bleeding.

- Method: Administration of medications that promote vasoconstriction.

- Examples:

- Adrenaline (Epinephrine): Can be added to saline or sodium bicarbonate for washing out an organ to encourage vessel constriction (e.g., in some urological procedures, often done two-hourly).

- Ergometrine: Used post-partum to stimulate uterine contractions and reduce bleeding after the birth of the placenta.

- Vasopressin (Pitressin): Can be used effectively in the control of bleeding from oesophageal varices by causing splanchnic vasoconstriction.

- Method: Administering agents that correct clotting factor deficiencies.

- Application: Very valuable when the mechanism of clotting is deficient.

- Vitamin K (IM): Important in jaundiced patients or those with liver dysfunction who are bleeding due to impaired synthesis of Vitamin K-dependent clotting factors.

- Factor VIII Concentrate: Indicated in patients with Haemophilia A.

- Fresh Frozen Plasma (FFP), Platelets, Cryoprecipitate: Administered to provide clotting factors or platelets as needed.

- Method: Using specialized materials to provide internal pressure or promote clotting.

- Examples:

- Gauze soaked in adrenaline can be effective in certain sites (e.g., nasal packing for epistaxis).

- Oxycel (oxidized regenerated cellulose), Fibrin glue, or a piece of the patient’s own crushed muscle can be used to promote local haemostasis in surgical beds.

- Method: Systemic antibiotic administration.

- Application: Essential in secondary haemorrhage, especially when caused by infection, to control sepsis which contributes to vessel wall breakdown.

- Method: Applying pressure from within a lumen using an inflatable balloon.

- Application: Applied by the balloon of a triluminal tube (e.g., Sengstaken-Blakemore tube) in bleeding oesophageal varices or by the balloon of a Foley catheter in a post-prostatectomy cavity.

- Method: Use of medications that inhibit the breakdown of blood clots.

- Example: Achieved by the use of Tranexamic Acid (TXA), which stabilizes clots and reduces bleeding in various conditions.

II. Restoration of Blood Volume and Oxygen Carrying Capacity

Replacing lost fluid and blood is crucial to maintain adequate circulation and tissue perfusion.

- Airway: Ensure a patent airway. Intubation may be necessary if consciousness is compromised to protect the airway and facilitate ventilation.

- Breathing: Assess respiratory effort and oxygenation. Administer high-flow oxygen (e.g., via non-rebreather mask) to maximize oxygen delivery to tissues. Provide ventilatory support if needed.

- Circulation: This is paramount.

- Large-Bore IV Access: Establish at least two large-bore intravenous (IV) lines (e.g., 14-16 gauge) for rapid fluid and blood product administration. Central venous access may be needed in severe cases.

- Fluid Resuscitation: Begin rapid infusion of crystalloid solutions (e.g., 0.9% Normal Saline, Lactated Ringer's) as initial volume expanders while awaiting blood products. Monitor response.

- Blood Transfusion: Initiate blood product transfusion (e.g., packed red blood cells to increase oxygen-carrying capacity; fresh frozen plasma for clotting factors; platelets for thrombocytopenia) as soon as possible, especially for significant haemorrhage. Consider massive transfusion protocols (MTP) for severe, ongoing bleeding.

- Disability (Neurological Status): Assess the patient's level of consciousness (e.g., AVPU scale, GCS) to monitor cerebral perfusion and detect neurological changes.

- Exposure and Environment: Fully expose the patient to identify all injuries and bleeding sites. Prevent hypothermia by covering the patient with warm blankets, as hypothermia significantly exacerbates coagulopathy and metabolic acidosis.

- Continuous Monitoring: Continuously monitor vital signs (heart rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation), ECG for cardiac rhythm, and hourly urine output via an indwelling urinary catheter (a sensitive indicator of renal perfusion). An arterial line provides continuous and accurate blood pressure monitoring.

- Laboratory Monitoring: Frequent serial blood tests are essential:

- Complete Blood Count (CBC): To monitor hemoglobin and hematocrit.

- Electrolytes and Renal Function Tests: To assess fluid and electrolyte balance and kidney function.

- Coagulation Profile: PT, PTT, fibrinogen to assess clotting status.

- Blood Type and Cross-match: For blood product compatibility.

- Lactate Levels: To assess tissue perfusion and severity of acidosis.

- Arterial Blood Gases (ABGs): For oxygenation, ventilation, and acid-base balance.

- Temperature Control: Actively maintain normothermia using warming blankets and warmed fluids.

- Correct Coagulopathy: Actively manage any identified clotting factor deficiencies by administering specific factor concentrates, cryoprecipitate, or prothrombin complex concentrates (PCCs), especially if the patient is on anticoagulants or has a pre-existing coagulopathy.

A. Nursing Diagnoses for Patients with Haemorrhage (Examples)

Nursing diagnoses are clinical judgments about individual, family, or community responses to actual or potential health problems/life processes. For haemorrhage, they often focus on perfusion, fluid balance, and anxiety.

- Deficient Fluid Volume related to active blood loss, as evidenced by hypotension, tachycardia, decreased urine output, cool/clammy skin, and altered mental status.

- Ineffective Tissue Perfusion (specify: Cerebral, Cardiopulmonary, Renal, Gastrointestinal, Peripheral) related to hypovolemia and decreased oxygen-carrying capacity, as evidenced by altered mental status, oliguria, delayed capillary refill, weak pulses, or abnormal ABGs.

- Decreased Cardiac Output related to reduced preload (due to blood loss), as evidenced by hypotension, tachycardia, and signs of hypoperfusion.

- Risk for Shock related to uncompensated blood loss.

- Anxiety/Fear related to threat to health status, perceived loss of control, and critical illness.

- Risk for Imbalanced Body Temperature (Hypothermia) related to hypovolemia, decreased metabolic rate, and rapid fluid resuscitation.

- Acute Pain related to injury or invasive procedures, as evidenced by patient report, guarding behavior, or vital sign changes.

B. Nursing Interventions for Haemorrhage

Nursing interventions are actions designed to achieve patient outcomes related to the nursing diagnoses. These are broad categories and require specific adaptation based on the individual patient's condition and the type of haemorrhage.

- Prioritize ABCs and Rapid Response:

- Immediately assess and maintain airway patency, breathing effectiveness, and circulation.

- Activate rapid response team/code team according to facility protocol for acute haemorrhage.

- Stay with the patient; do not leave an acutely bleeding patient unattended.

- Control Bleeding (Nursing Actions):

- Apply direct, firm pressure to any external bleeding site using sterile dressings. Elevate the affected limb if appropriate.

- Prepare and assist with tourniquet application if indicated for life-threatening limb haemorrhage (monitor time).

- Prepare for and assist with surgical or interventional radiology procedures for definitive bleeding control.

- Ensure all lines, drains, and tubes are securely in place to prevent accidental dislodgement.

- Fluid and Blood Volume Resuscitation:

- Establish and maintain multiple large-bore IV access sites.

- Administer prescribed IV fluids (crystalloids) and blood products (PRBCs, FFP, platelets) rapidly, using rapid infusers if available, and monitor patient response.

- Monitor for signs of fluid overload or transfusion reactions.

- Ensure warmed fluids and blood products are used to prevent hypothermia.

- Continuous Assessment and Monitoring:

- Monitor vital signs (BP, HR, RR, SpO2, Temp) continuously (e.g., every 5-15 minutes or more frequently in acute phase).

- Assess level of consciousness (LOC) and neurological status frequently for signs of cerebral hypoperfusion.

- Monitor hourly urine output via indwelling catheter; report output less than 0.5 mL/kg/hour.

- Assess skin color, temperature, and capillary refill for signs of peripheral perfusion.

- Monitor dressing for increasing saturation and measure blood loss (e.g., weigh pads, assess drainage in collection devices).

- Review and trend laboratory results (Hgb, Hct, lactate, coagulation studies, electrolytes).

- Assess for signs of internal bleeding if concealed haemorrhage is suspected (e.g., increasing abdominal girth, distension, pain, bruising, changes in bowel sounds, persistent hypotension despite fluid resuscitation).

- Oxygenation and Respiratory Support:

- Administer oxygen as prescribed to maintain SpO2 >94%.

- Monitor respiratory effort and patterns; prepare for ventilatory support if respiratory distress or failure occurs.

- Maintain Normothermia:

- Use warming blankets, warmed IV fluids, and control room temperature to prevent and treat hypothermia.

- Pain and Anxiety Management:

- Administer analgesics as prescribed, carefully monitoring for effects on vital signs.

- Provide emotional support, calm reassurance, and clear, concise explanations to the patient and family. Address their fears and anxiety.

- Create a calm environment as much as possible.

- Prevent Complications:

- Maintain strict asepsis for all invasive procedures (IV insertion, catheter care) to prevent infection.

- Implement measures to prevent pressure injuries due to immobility and hypoperfusion.

- Initiate DVT prophylaxis as soon as appropriate and ordered.

- Monitor for signs of acute kidney injury or multi-organ dysfunction.

- Documentation and Communication:

- Accurately and timely document all assessments, interventions, and patient responses.

- Communicate effectively and frequently with the interdisciplinary team (physicians, respiratory therapists, lab, blood bank) regarding patient status and changes.

- Handover critical information thoroughly.

Special Types and Terms of Haemorrhage

Haemorrhage can manifest in various specific ways depending on its anatomical location, and certain terms are used to describe these particular presentations.

Specific Types of Haemorrhage

These are haemorrhages that are identified by their site of external manifestation or unique characteristics:

Epistaxis (Nosebleed):- Description: Bleeding from the nose.

- Common Causes:

- Injury to the nose (trauma).

- Fracture base of the skull (indicating severe trauma).

- Ulceration of the mucus membrane of the nose (e.g., from dryness, digital manipulation).

- Bleeding disorders (e.g., leukemia, haemophilia).

- Local infections like rhinitis.

- Venous congestion associated with heart diseases (e.g., heart failure).

- Hypertension (high blood pressure).

- Management:

- Initial First Aid: The patient should sit upright, leaning slightly forward (not backward, to prevent blood from flowing down the throat), and firm pressure should be applied to the soft cartilaginous part of the nostrils for 10-15 minutes.

- Sponge the face with cold water or apply a cold compress to the bridge of the nose.

- If bleeding persists, medical attention is required.

- Medical Interventions:

- The nose may be packed with sterile gauze, sometimes impregnated with vasoconstrictors like adrenaline, or specialized nasal packing devices.

- The nasal plug/pack is typically left in situ for 24-48 hours, with careful monitoring due to the risk of infection (sepsis) and potential airway obstruction.

- Recurrent or persistent bleeding may be treated by chemical (e.g., silver nitrate) or electrical (electrocautery) cauterization of the bleeding vessel.

- In severe cases, surgical ligation of feeding arteries or interventional radiology embolization may be necessary.

- Description: This is the coughing up of blood from the respiratory tract (lungs or bronchial tubes). The blood is typically bright red, frothy (mixed with air), and alkaline. It is often mixed with sputum.

- Common Causes:

- Pulmonary diseases (e.g., Tuberculosis (TB), Bronchiectasis, Pneumonia, Lung abscess).

- Lung cancer (bronchogenic carcinoma).

- Benign tumours of the respiratory tract.

- Injury to the lungs or chest (trauma).

- Pulmonary embolism (especially with infarction).

- Venous congestion into the lungs (e.g., severe heart failure, mitral stenosis).

- Blood disorders (e.g., leukemia, coagulopathies).

- Rupture of an aortic aneurysm into a bronchus (rare but life-threatening).

- Foreign body aspiration.

- Management:

- Immediate Action: Severe cases require urgent medical assessment and treatment to secure the airway and control bleeding.

- Patient Care:

- Maintain a calm environment and reassure the patient (care of the mind).

- Position the patient sitting up to aid breathing and prevent aspiration; usually, the bleeding side down if known, to protect the contralateral lung.

- Ensure total rest.

- Frequent mouth washes to remove the taste of blood.

- Provide non-stimulating fluids.

- Keep the patient warm.

- Medical Interventions:

- Collect blood for Hemoglobin (HB) estimation, blood grouping, and cross-matching for potential transfusion.

- Blood transfusion if bleeding is severe and causing hemodynamic instability.

- Administer antitussives (e.g., codeine, morphine) to suppress cough, which can exacerbate bleeding, and to provide sedation.

- Treat the underlying cause (e.g., antibiotics for infection, chemotherapy/radiation for cancer, bronchoscopic intervention).

- Bronchoscopy for localization and intervention (e.g., laser coagulation, balloon tamponade).

- In severe cases, surgical resection may be considered.

- Description: This is vomiting blood from the upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract (esophagus, stomach, or duodenum). The blood may be bright red (indicating active, fresh bleeding) but is more often brown, resembling "coffee grounds" due to the action of gastric acid on hemoglobin. It is acidic.

- Common Causes:

- Peptic ulcers (gastric or duodenal ulcers).

- Acute gastritis (inflammation of the stomach lining, often due to corrosive drugs like NSAIDs/Aspirin, or alcohol taken on an empty stomach).

- Gastric cancer.

- Oesophageal varices (dilated veins in the esophagus, often due to portal hypertension, e.g., in liver cirrhosis).

- Mallory-Weiss tear (tear in the esophageal lining due to forceful vomiting/retching).

- Swallowed blood (e.g., after severe epistaxis or haemoptysis).

- Fracture base of the skull (blood from nasopharynx tracking down).

- Post-operative bleeding after nose and throat surgeries.

- Blood disorders (e.g., leukemia, coagulopathies).

- Management:

- Initial Assessment: Immediate assessment of hemodynamic stability.

- Investigations:

- Collect blood for HB, grouping, and cross-matching.

- Stool for occult blood test.

- Patient Care:

- Ensure absolute rest and quietness.

- Frequent monitoring of vital signs.

- Provide emotional support.

- Medical Interventions:

- Fluid resuscitation and blood transfusion if indicated.

- Administer morphine for pain and sedation as needed, while carefully monitoring respiratory status and vital signs.

- Specific Treatment According to Cause:

- Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) for ulcers/gastritis.

- Endoscopic intervention (e.g., banding, sclerotherapy for varices; clipping, coagulation for ulcers).

- Surgical intervention for refractory cases or severe bleeds not amenable to endoscopy.

- General nursing care including NPO (nothing by mouth) and monitoring for further bleeding.

- Description: This is the passage of dark, tarry, sticky stools (faeces) with a characteristic foul odor. It results from bleeding in the upper GI tract, where blood has been digested and altered by intestinal bacteria. Usually indicates bleeding from a site high in the GIT (esophagus, stomach, duodenum, or small bowel).

- Common Causes:

- Duodenal ulcers (most common cause).

- Gastric ulcers.

- Gastritis.

- Bleeding from the small bowel.

- Swallowing of a large amount of blood (e.g., from severe epistaxis or haemoptysis).

- Certain medications like iron supplements (can cause dark stools, but not true melaena, which is positive for occult blood) or bismuth subsalicylate.

- Investigation: Stool for occult blood (guaiac test) confirms the presence of blood. Endoscopy is usually required to identify the source.

- Management: As for internal haemorrhage, focusing on hemodynamic stabilization, identifying the source, and definitive treatment (often endoscopic or medical).

- Description: Is the passage of blood in urine, making it appear pink, red, or dark brown/cola-colored. It can be macroscopic (visible to the naked eye) or microscopic (detectable only with urinalysis).

- Common Causes:

- Trauma to the urinary tract (e.g., ruptured kidney, bladder injury).

- Urinary tract infections (UTIs).

- Renal calculi (kidney stones) – often associated with pain.

- Chronic kidney infection (pyelonephritis).

- Tuberculosis (TB) of the kidney.

- Post-operative causes (e.g., prostatectomy, bladder surgery).

- Growths/tumours in the bladder, kidney, or prostate (can be painless haematuria, requiring urgent investigation).

- Leukemia or other blood disorders affecting clotting.

- Inflammation of the urinary tract (e.g., cystitis, glomerulonephritis, bilharzia/schistosomiasis).

- Certain medications (e.g., anticoagulants).

- Management:

- Less Severe Cases: Rest in bed and reassurance, along with treatment of the underlying cause.

- More Severe Cases: If there's significant damage to the bladder or kidneys, or a mass, surgical intervention (e.g., to remove stones, excise tumors, repair trauma) may be indicated.

- Specific treatment varies significantly according to the underlying cause. This may include antibiotics for infection, medical management for kidney disease, or interventional procedures for stones/tumors.

Special Terms for Haemorrhage from Specific Sites/Contexts

These terms describe the location of blood accumulation or specific bleeding patterns:

- Haemothorax: Bleeding into the pleural cavity (space between the lungs and the chest wall). Often due to chest trauma or lung pathology.

- Haemoperitoneum: Bleeding into the peritoneal cavity (abdominal cavity). Often associated with ruptured organs (e.g., spleen, liver) or major vessel injury.

- Haemarthrosis: Bleeding into a joint space. Common in individuals with bleeding disorders like haemophilia or following trauma.

- Menorrhagia: Excessive or prolonged menstrual bleeding at regular intervals.

- Metrorrhagia: Irregular, acyclic uterine bleeding occurring between expected menstrual periods.

- Menometrorrhagia: Prolonged or excessive bleeding occurring at irregular and frequent intervals.

- Haemopericardium: Bleeding into the pericardial sac (the sac surrounding the heart). Can lead to cardiac tamponade, a life-threatening condition.

- Haematomyelia: Bleeding into the spinal cord parenchyma.

- Haematoma: A localized collection of extravasated blood, usually clotted, in an organ, space, or tissue (e.g., a bruise).

- Ecchymosis: A discoloration of the skin resulting from bleeding underneath, typically caused by bruising. Larger than petechiae.

- Petechiae: Small (1-2 mm), pinpoint, non-blanching red or purple spots on the skin caused by minor hemorrhage.

- Purpura: Red or purple discolored spots on the skin that do not blanch on pressure, caused by bleeding underneath the skin. Larger than petechiae but smaller than ecchymoses.