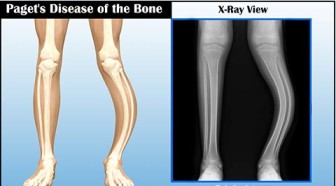

Paget’s disease of bone is a disorder in which there’s a lot of bone remodeling that happens in some regions of the bone. There’s excessive bone resorption followed by excessive bone growth, and that leads to skeletal deformities and potential fractures.

Paget's disease of bone, also known as osteitis deformans, is a chronic and progressive disorder of localized abnormal bone remodeling.

It is characterized by an excessive and disorganized breakdown and formation of bone tissue.

- Chronic and Progressive: This means it's a long-lasting condition that tends to worsen over time if not managed. It's not a self-limiting illness.

- Localized Abnormal Bone Remodeling:

- Localized: Unlike osteoporosis, which affects the entire skeleton, Paget's disease typically affects specific bones or areas within bones. Common sites include the pelvis, spine, skull, and long bones of the legs (femur, tibia). It can be monostotic (affecting one bone) or polyostotic (affecting multiple bones).

- Abnormal Bone Remodeling: In healthy bone, a continuous process of remodeling occurs, where old bone is resorbed by osteoclasts and new bone is formed by osteoblasts. This process is tightly coupled and balanced, maintaining bone strength and integrity. In Paget's disease, this balance is severely disrupted:

- Excessive Bone Resorption: There's an initial phase of markedly increased and uncontrolled osteoclastic activity, leading to rapid breakdown of existing bone.

- Compensatory Excessive Bone Formation: In response to the rapid bone resorption, osteoblasts become hyperactive, attempting to rebuild bone. However, this new bone is laid down haphazardly, in a chaotic and disorganized fashion, rather than in the structured lamellar pattern of healthy bone.

- Disorganized, Enlarged, and Weakened Bone: The result of this chaotic remodeling process is bone that is:

- Disorganized (Woven Bone): Instead of strong, parallel lamellae, the new bone has a "woven" or "mosaic" pattern, making it structurally unsound.

- Enlarged: The affected bones often become abnormally thick and enlarged due to the excessive deposition of new bone.

- Weakened: Despite being enlarged, the pagetic bone is mechanically weaker than normal bone. This makes it more susceptible to deformities, bowing, and fractures.

The pathophysiology of Paget's disease is characterized by a focal (localized) acceleration of normal bone remodeling, resulting in the production of bone that is architecturally unsound. This abnormal process occurs in three main phases:

- Lytic Phase (Osteoclastic Phase):

- Initiation: The disease typically begins with a dramatic increase in osteoclastic activity. Osteoclasts are the cells responsible for bone resorption (breaking down old bone).

- Giant Osteoclasts: In pagetic lesions, the osteoclasts are unusually large (often containing 10-100 nuclei, compared to 2-10 in normal osteoclasts) and significantly more numerous and active than normal osteoclasts.

- Rapid Resorption: These hyperactive osteoclasts resorb bone at an extremely high rate, creating extensive areas of bone breakdown. This leads to bone loss and weakening in the affected area. This initial phase can be difficult to detect clinically and may not cause symptoms.

- Mixed Phase (Osteoclastic-Osteoblastic Phase):

- Compensatory Osteoblastic Activity: As a direct response to the excessive bone resorption, there is a compensatory increase in osteoblastic activity. Osteoblasts are the cells responsible for forming new bone.

- Rapid, Disorganized Bone Formation: However, the new bone formed by these osteoblasts is laid down in a chaotic, disorganized, and accelerated manner. Instead of the typical, strong lamellar bone (well-organized layers), a large quantity of immature, woven bone is produced.

- Vascularity: The affected bone becomes highly vascularized (rich in blood vessels) during this phase, which can contribute to warmth over the pagetic lesions.

- Bone Enlargement: The excessive and rapid formation of disorganized bone leads to an overall increase in bone mass and enlargement of the affected bone.

- Sclerotic Phase (Quiescent or Osteoblastic Phase):

- Reduced Activity: In this final phase, osteoclastic activity decreases, and osteoblastic activity also slows down, but the bone formation continues to be disorganized.

- Dense, Sclerotic Bone: The bone becomes very dense, thick, and sclerotic (hardened), but it retains its disorganized, woven structure with a characteristic "mosaic" pattern on microscopic examination (interlocking fragments of lamellar bone separated by prominent cement lines).

- Mechanical Weakness: Despite its apparent density and thickness, this pagetic bone remains mechanically weak, brittle, and prone to deformity and fracture due to its abnormal architecture. It does not have the intrinsic strength of normal, well-structured lamellar bone.

- Osteoclast Dysfunction: The primary defect is believed to reside within the osteoclast. Pagetic osteoclasts are not only larger and more numerous but also exhibit increased sensitivity to various stimuli that promote bone resorption.

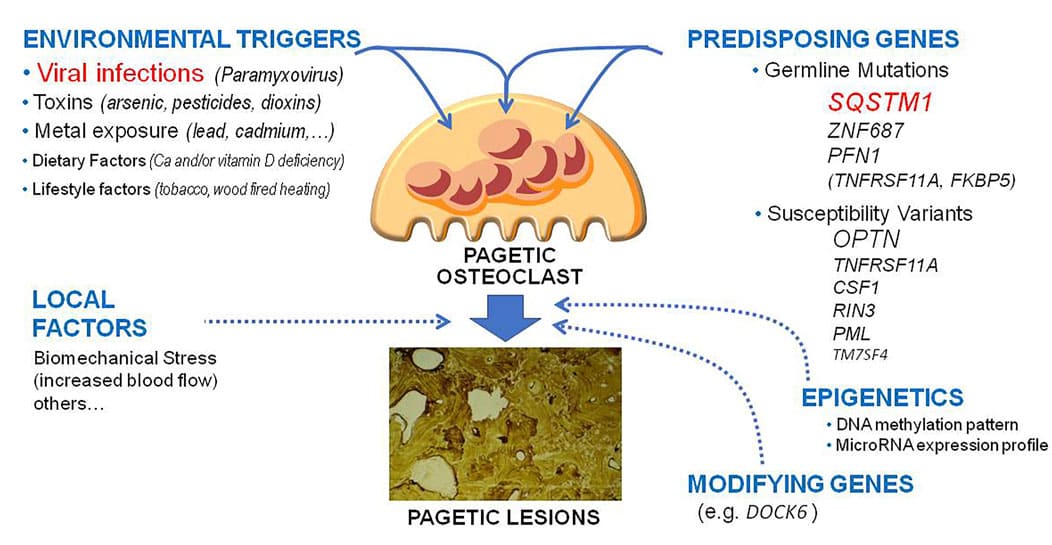

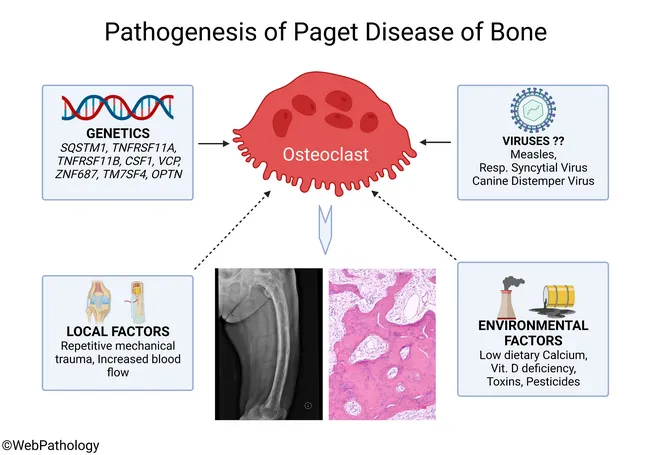

- Genetic Factors: Mutations in the SQSTM1 gene (sequestosome 1, also known as p62) are found in a significant proportion of familial Paget's disease cases and some sporadic cases. This gene is involved in regulating osteoclast function.

- Viral Hypothesis: For many years, a slow virus infection (paramyxoviruses like measles virus or canine distemper virus) was suspected as a causative agent, based on the presence of viral-like inclusions in pagetic osteoclasts. While this hypothesis is still investigated, it's not universally accepted as the sole cause, and viral RNA/proteins are not consistently found. The current understanding often views it as a "genetic predisposition with an environmental trigger" model, where a viral infection might act as a trigger in genetically susceptible individuals.

- Cytokine and Growth Factor Dysregulation: There is evidence of altered local production and sensitivity to cytokines (e.g., IL-6) and growth factors (e.g., M-CSF, IGF-1, TGF-beta) in pagetic bone, which can promote both osteoclast and osteoblast activity.

The exact cause (etiology) of Paget's disease is not fully understood, but it is believed to involve a complex interplay of genetic predisposition and environmental factors. It is generally not considered a cancer, nor is it contagious.

Genetics play a significant role, with approximately 15-40% of individuals with Paget's disease reporting a family history of the condition.

- SQSTM1 Gene Mutation:

- Most Common: The most well-established genetic link is to mutations in the SQSTM1 gene (sequestosome 1, also known as p62).

- Function: This gene provides instructions for making a protein that plays a role in various cellular processes, including osteoclast differentiation and function. Mutations in SQSTM1 lead to hyperactivity of osteoclasts, which is the hallmark initial event in Paget's disease.

- Prevalence: SQSTM1 mutations are found in a high percentage (40-50%) of familial cases and 10-15% of sporadic (non-familial) cases.

- Penetrance: Not everyone with an SQSTM1 mutation will develop Paget's disease, indicating incomplete penetrance. This suggests other factors are needed for the disease to manifest.

- Other Genetic Loci: Other genes and genetic regions have been implicated, particularly those involved in cellular signaling pathways (like RANK-RANKL-OPG system) and immune responses, but SQSTM1 is the most significant.

- Family History: Having a first-degree relative (parent, sibling, child) with Paget's disease significantly increases an individual's risk.

While not definitively proven as sole causes, several environmental factors have been investigated as potential triggers in genetically susceptible individuals.

- Viral Infection Hypothesis:

- Persistent Theory: This remains a leading environmental hypothesis. It suggests that a slow virus infection (paramyxoviruses, particularly measles virus or canine distemper virus) may trigger the disease in individuals with a genetic predisposition.

- Evidence: Viral-like nuclear inclusions (containing viral nucleocapsid material) have been observed in pagetic osteoclasts, though this finding is not universal and can be controversial due to detection methods.

- Mechanism: It's hypothesized that the virus alters osteoclast function, making them more sensitive to activating factors and leading to uncontrolled bone resorption.

- Geographic Distribution:

- Historical Observation: Paget's disease has a distinct geographic distribution, being more common in people of Anglo-Saxon descent and those living in certain parts of Europe (e.g., UK, France, Germany) and areas with historical migration from these regions (e.g., Australia, New Zealand, USA).

- Declining Incidence: There has been a notable decline in the incidence and severity of Paget's disease in many Western countries over the past few decades. This decline is difficult to explain by genetic factors alone and lends some support to a changing environmental trigger (e.g., decreased exposure to certain viruses, improved public health).

- Toxic Exposure: Some older theories considered exposure to certain toxins or lead as potential factors, but these are less supported by current research.

Based on the etiology, key risk factors include:

- Age: The prevalence of Paget's disease increases significantly with age. It is rare before the age of 40 and becomes more common in individuals over 50.

- Ethnicity/Ancestry: More common in populations of Western European descent. Less common in individuals of African or Asian descent.

- Family History: As mentioned, a strong family history is a major risk factor.

- Sex: Affects men slightly more often than women.

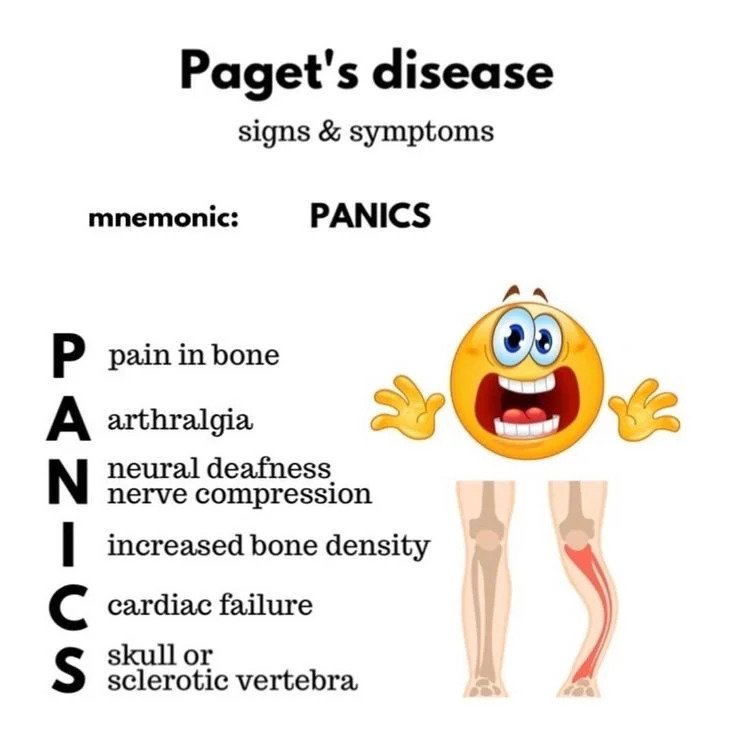

The clinical manifestations of Paget's disease are highly variable, ranging from asymptomatic (no symptoms) to severe and debilitating.

- Bone Pain:

- Most Common Symptom: Often described as a deep, aching, constant, and dull pain. It can be worse at night or with weight-bearing.

- Cause: Due to increased bone turnover, microfractures, nerve compression, or secondary osteoarthritis in affected joints.

- Location: Depends on the affected bone(s). Common sites of pain correspond to common sites of disease (pelvis, spine, skull, long bones).

- Bone Deformity:

- Enlargement: Bones may become visibly enlarged. This is most noticeable in the skull (hat size increases) or long bones.

- Bowing: Long bones (e.g., tibia, femur) can develop bowing, leading to changes in gait. A bowed leg might appear shorter or cause a waddling gait.

- Spinal Curvature: Vertebral involvement can lead to kyphosis (exaggerated outward curvature of the thoracic spine) or scoliosis.

- Facial Changes: Rarely, if facial bones are involved, it can lead to facial asymmetry.

- Warmth Over Affected Bone:

- Cause: Due to the increased vascularity in active pagetic lesions, the skin over affected bones may feel warm to the touch.

- Skull Involvement:

- Headache: Common symptom.

- Increased Hat Size: The most classic sign of skull enlargement.

- Deafness/Hearing Loss (Conductive or Sensorineural): A significant and common complication, resulting from compression of cranial nerves (especially cranial nerve VIII) due to bone enlargement, or direct involvement of the ossicles in the middle ear.

- Vertigo/Dizziness.

- Basilar Invagination: Rarely, softening of the skull base can lead to invagination of the skull into the foramen magnum, causing brainstem or cerebellar compression.

- Spinal Involvement:

- Back Pain: Often indistinguishable from other causes of back pain, but can be severe.

- Spinal Stenosis: Enlargement of vertebrae can narrow the spinal canal, compressing the spinal cord or nerve roots, leading to radiculopathy, weakness, numbness, or even paraplegia (rare).

- Kyphosis/Scoliosis: As mentioned, vertebral collapse or reshaping can cause spinal deformities.

- Long Bone Involvement (e.g., Femur, Tibia):

- Pain: Often localized to the affected bone.

- Bowing: Femur or tibia may bow, causing gait disturbances and stress on joints.

- Fractures (Pathological Fractures): The disorganized bone is weak and prone to fractures, often transverse or "chalk stick" fractures. These can occur with minimal trauma.

- Secondary Osteoarthritis: Joint involvement (especially hips, knees) can occur due to altered biomechanics, bone deformity, and stress on articular cartilage.

- Pelvic Involvement:

- Pain: Common, often radiating to the hips or lower back.

- Gait Abnormalities.

- Secondary Osteoarthritis of the Hip.

- Cardiovascular Complications (Rare in localized disease, more common in extensive polyostotic disease):

- High-Output Cardiac Failure: The increased vascularity of extensive pagetic bone acts like an arteriovenous shunt, increasing cardiac output and potentially leading to heart failure in severe, widespread disease.

- Neurological Complications:

- Nerve Entrapment: Enlarged bone can compress peripheral nerves or cranial nerves, leading to pain, weakness, or sensory deficits (e.g., hearing loss, visual disturbances, facial nerve palsy).

- Hydrocephalus: Very rare, due to obstruction of CSF flow from basilar invagination.

- Malignant Transformation (Osteosarcoma):

- Rare but Serious: The most feared complication is the development of osteosarcoma (or fibrosarcoma/chondrosarcoma) within a pagetic lesion.

- Risk Factors: More common in polyostotic disease, older age, and long-standing disease.

- Symptoms: Sudden, severe increase in pain, swelling, or rapid enlargement of a pagetic bone.

- Prognosis: Generally poor due to late diagnosis and aggressive nature.

- Hypercalcemia (Rare):

- Usually only occurs if an individual with extensive, severe Paget's disease is immobilized (e.g., bed rest after a fracture), as the reduced mechanical stress shifts the balance towards resorption, leading to calcium release into the bloodstream.

The diagnosis of Paget's disease relies on a combination of clinical assessment, biochemical markers, and imaging studies.

- History:

- Symptoms: Inquire about bone pain (onset, character, location, aggravating/alleviating factors), bone deformities (e.g., increasing hat size, bowing of limbs), hearing loss, headaches, or neurological symptoms.

- Family History: A positive family history significantly increases suspicion.

- Physical Examination:

- Inspection: Look for visible deformities (e.g., skull enlargement, kyphosis, bowed long bones).

- Palpation: Check for warmth over affected bones, tenderness, or masses.

- Neurological Assessment: Evaluate for signs of nerve compression (e.g., hearing deficits, motor weakness, sensory changes).

- Gait Analysis: Observe for gait abnormalities due to pain or limb bowing.

These reflect the high rate of bone turnover characteristic of Paget's disease.

- Serum Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP):

- Key Diagnostic Marker: Elevated serum total ALP is the most common and sensitive biochemical indicator of active Paget's disease, especially when bone-specific ALP is also elevated.

- Source: ALP is an enzyme produced by osteoblasts during bone formation. Its elevation reflects the increased osteoblastic activity trying to compensate for excessive osteoclastic resorption.

- Correlation: The level of elevation generally correlates with the extent and activity of the disease.

- Considerations: Other conditions can also elevate ALP (e.g., liver disease, growing children, bone healing). If total ALP is elevated, checking bone-specific ALP or liver function tests (LFTs) can differentiate the source. Gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) is a liver enzyme; if GGT is normal, an elevated ALP is more likely to be from bone.

- Other Bone Turnover Markers:

- Urinary N-telopeptide (NTX) or C-telopeptide (CTX): These are markers of bone resorption and are often elevated.

- Serum Procollagen Type 1 N-terminal Propeptide (P1NP): A marker of bone formation, which can also be elevated.

- Use: While ALP is usually sufficient for diagnosis and monitoring, these markers can be useful in specific situations (e.g., normal total ALP but suspected Paget's, or to monitor treatment response when ALP is not significantly elevated).

- Serum Calcium and Phosphate:

- Typically Normal: In uncomplicated Paget's disease, serum calcium and phosphate levels are usually normal.

- Hypercalcemia: May occur if the patient with extensive disease is immobilized.

- Hypocalcemia: Can occur if patients are treated with potent bisphosphonates without adequate calcium and vitamin D supplementation.

Imaging is crucial for identifying affected bones, assessing the extent of the disease, and detecting complications.

- Plain Radiographs (X-rays):

- Initial Imaging: Often the first and most diagnostic imaging modality.

- Characteristic Features:

- Lytic Phase: V-shaped "cutting cone" or "blade of grass" appearance (lucent, resorptive front advancing through cortical bone) in long bones.

- Mixed/Sclerotic Phase:

- Bone Enlargement: Thickening and expansion of the cortex, often with loss of distinction between cortex and medulla.

- Disorganized Trabeculae: Coarsened, prominent, and chaotic trabecular pattern (a "cotton wool" appearance, especially in the skull).

- Bowing: Deformity of long bones.

- Vertebral Changes: "Picture frame" vertebrae (thickened cortices).

- Limitations: Detects only affected areas and may not reveal early lesions or the full extent of active disease.

- Radionuclide Bone Scan (Technetium-99m Methylene Diphosphonate - MDP Scan):

- Highly Sensitive: The most sensitive imaging modality for detecting active pagetic lesions throughout the entire skeleton, even before they are visible on X-rays or cause symptoms.

- Mechanism: Increased uptake of the tracer in areas of high metabolic bone activity (both resorption and formation).

- Appearance: Shows "hot spots" in affected bones.

- Use: Excellent for determining the extent of the disease (monostotic vs. polyostotic) and identifying all active sites that may require treatment.

- Computed Tomography (CT) Scan:

- Detailed Bone Anatomy: Provides more detailed cross-sectional images of bone than X-rays.

- Use: Useful for evaluating skull and spinal involvement (e.g., assessing nerve impingement, spinal stenosis, basilar invagination) and for planning surgical procedures.

- Detection of Complications: Good for detecting osteosarcoma or stress fractures.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI):

- Soft Tissue Detail: Excellent for visualizing soft tissues, including nerves, spinal cord, and bone marrow.

- Use: Indicated when neurological complications are suspected (e.g., spinal cord compression, nerve entrapment), or to evaluate for malignant transformation (osteosarcoma).

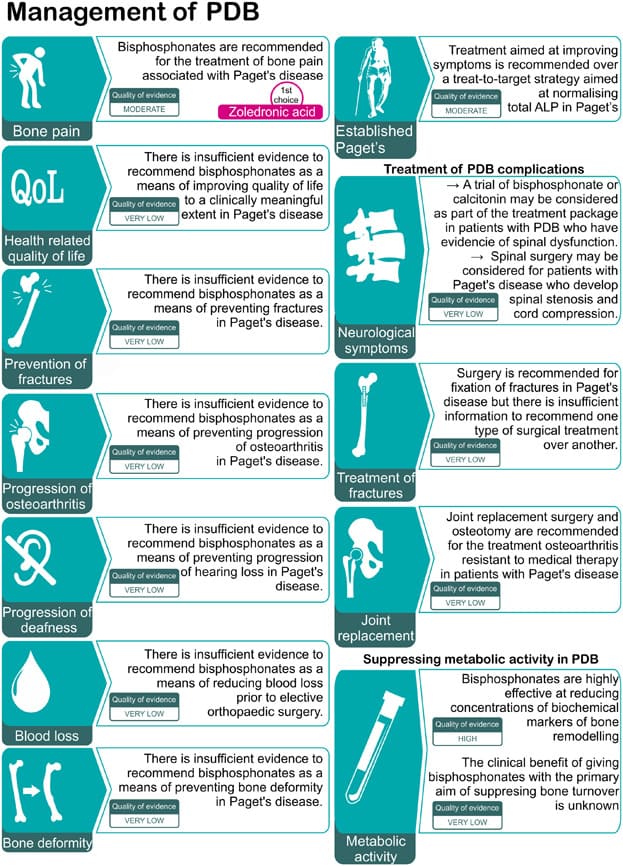

There is no cure for Paget’s disease and no way to reverse its effects on bone.

The primary goals of managing Paget's disease are to control symptoms, prevent complications, and normalize the abnormal bone remodeling process.

Not all patients with Paget's disease require treatment, especially if they are asymptomatic with mildly elevated alkaline phosphatase (ALP). However, treatment is generally recommended for:

- Symptomatic Disease: Bone pain, headache, nerve compression symptoms, etc.

- Asymptomatic Patients with Active Disease in Critical Locations:

- Weight-bearing bones: To prevent deformity and fracture (e.g., femur, tibia, pelvis, vertebrae).

- Skull: To prevent hearing loss or neurological complications.

- Bones adjacent to major joints: To prevent or mitigate secondary osteoarthritis.

- Preventing Complications: Before orthopedic surgery (e.g., joint replacement) on a pagetic bone to reduce blood loss and improve healing.

- Very High ALP Levels: Even if asymptomatic, a significantly elevated ALP might warrant treatment to reduce the long-term risk of complications.

The cornerstone of medical treatment for Paget's disease is bisphosphonates, which are potent inhibitors of osteoclastic bone resorption.

- Bisphosphonates:

- Mechanism of Action: These drugs are taken up by osteoclasts and inhibit their activity, thereby reducing bone breakdown. This leads to a subsequent decrease in osteoblastic activity and normalization of bone turnover.

- Goals: Reduce bone pain, normalize biochemical markers (especially ALP), and prevent progression of bone lesions and complications.

- Types:

- Aminobisphosphonates (Potent):

- Zoledronic Acid (IV): Considered the most potent and effective bisphosphonate for Paget's disease. A single intravenous (IV) infusion can induce long-term remission (often for years). Side effects can include acute phase reaction (fever, flu-like symptoms) within days of infusion, and rarely, osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ) or atypical femoral fractures with prolonged use.

- Risedronate (Oral): Effective oral option.

- Alendronate (Oral): Another effective oral bisphosphonate.

- Ibandronate: Less commonly used for Paget's.

- Non-aminobisphosphonates (Less Potent):

- Etidronate, Tiludronate: Older agents, less potent and often associated with more mineralization defects; rarely used now.

- Aminobisphosphonates (Potent):

- Administration: Oral bisphosphonates require careful administration (empty stomach, with plain water, remaining upright for 30-60 minutes) to ensure absorption and prevent esophageal irritation.

- Monitoring: Treatment response is monitored by serial measurements of serum ALP. Remission is typically defined as normalization of ALP, or a reduction to the patient's individual normal range.

- Pre-treatment: Adequate calcium and vitamin D levels are crucial before and during bisphosphonate therapy to prevent hypocalcemia.

- Calcitonin (Less Common Now):

- Mechanism of Action: A hormone that directly inhibits osteoclast activity.

- Administration: Administered subcutaneously or intranasally.

- Use: While effective in reducing pain and ALP levels, it is less potent than bisphosphonates and has a shorter duration of action. It's now rarely used as a first-line agent, mostly reserved for patients who cannot tolerate bisphosphonates or have contraindications. Side effects can include flushing, nausea, and local injection site reactions.

- Other Analgesics:

- NSAIDs (Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs): Can help manage bone pain.

- Acetaminophen: For mild pain.

- Opioids: May be used for severe, intractable pain, but with caution due to side effects and potential for dependence.

- Pain Management: Besides medications, heat/cold applications, massage, and physical therapy can help.

- Physical Therapy and Exercise:

- Maintain Mobility: Encourage regular, low-impact exercise (e.g., walking, swimming, cycling) to maintain strength, flexibility, and mobility.

- Strengthening: Exercises to strengthen muscles around affected joints can improve stability.

- Weight-Bearing: Important for maintaining bone health, but activities that put excessive stress on affected bones should be avoided.

- Assistive Devices:

- Orthotics/Braces: Can help support weakened limbs, correct gait abnormalities, or reduce stress on affected joints.

- Canes, Walkers: To aid mobility and reduce fall risk.

- Hearing Aids: For patients with significant hearing loss.

- Nutrition:

- Calcium and Vitamin D: Adequate intake is essential for overall bone health and to prevent secondary hyperparathyroidism, especially when taking bisphosphonates.

- Lifestyle Modifications:

- Weight Management: Maintaining a healthy weight reduces stress on weight-bearing joints.

- Fall Prevention: Modify the home environment to reduce fall risks.

Surgery is reserved for complications of Paget's disease.

- Osteotomy:

- Purpose: To correct severe bone deformities (e.g., bowed tibia or femur) and realign limbs, thereby improving function and reducing stress on joints.

- Timing: Often performed after medical therapy has reduced disease activity.

- Arthroplasty (Joint Replacement):

- Purpose: To relieve pain and improve function in joints severely affected by secondary osteoarthritis (e.g., hip or knee replacement).

- Considerations: Surgery on pagetic bone can be more challenging due to increased vascularity and altered bone structure, potentially leading to increased blood loss and higher risk of complications. Pre-treatment with bisphosphonates can help.

- Spinal Decompression:

- Purpose: To relieve pressure on the spinal cord or nerve roots caused by vertebral enlargement or collapse.

- Fracture Repair:

- Purpose: To stabilize pathological fractures. Internal fixation with rods or plates may be necessary.

- Serum ALP: Regular monitoring (e.g., every 3-6 months initially, then annually once stable) to assess disease activity and treatment response.

- Imaging: Repeat X-rays or bone scans are usually not routinely needed for monitoring unless there is a change in symptoms or suspicion of complications.

- Clinical Assessment: Ongoing evaluation of pain, neurological symptoms, and new deformities.

Nurses play a vital role in the care of patients with Paget's disease, focusing on symptom management, education, preventing complications, and supporting functional independence.

- Chronic Pain related to pathological bone changes, nerve compression, and/or secondary osteoarthritis.

- Impaired Physical Mobility related to bone pain, deformities, pathological fractures, and/or neurological deficits.

- Risk for Injury (Fractures) related to weakened and disorganized bone structure.

- Impaired Verbal Communication (Hearing Loss) related to cranial nerve compression or ossicle involvement in the skull.

- Disrupted Body Image related to skeletal deformities (e.g., enlarged skull, bowed limbs).

- Inadequate health Knowledge regarding disease process, treatment regimen, potential complications, and self-care strategies.

- Risk for Ineffective Health Maintenance related to chronic nature of the disease and need for ongoing therapy and monitoring.

- Activity Intolerance related to bone pain, muscle weakness, and/or cardiovascular complications (rare).

- Risk for Peripheral Neurovascular Dysfunction related to nerve compression by enlarging bone.

| Action | Detail/Rationale |

|---|---|

| Assessment |

|

| Administer Analgesics | Administer prescribed pain medications (NSAIDs, acetaminophen, opioids) on a regular schedule, and evaluate effectiveness. |

| Administer Bisphosphonates/Calcitonin | Administer as prescribed and monitor for side effects. Educate on proper oral bisphosphonate administration. |

| Non-pharmacological Pain Relief |

|

| Collaborate | With physical therapy for modalities (e.g., TENS unit) and exercises. |

| Action | Detail/Rationale |

|---|---|

| Assessment |

|

| Promote Safe Mobility |

|

| Prevent Fractures |

|

| Support Deformed Limbs | Use orthotic devices or braces as prescribed to support weakened or bowed limbs and improve stability. |

| Action | Detail/Rationale |

|---|---|

| Assessment |

|

| Facilitate Communication |

|

| Assistive Devices | Encourage and assist with the use of hearing aids as prescribed. |

| Referral | Collaborate with audiologist for comprehensive hearing evaluation and management. |

| Action | Detail/Rationale |

|---|---|

| Assessment |

|

| Provide Emotional Support |

|

| Educate | Provide accurate information about the disease to alleviate misconceptions. |

| Suggest Adaptive Strategies | Encourage use of clothing that camouflages deformities if desired. |

| Referral | Consider referral to support groups or counseling if psychological distress is significant. |

| Action | Detail/Rationale |

|---|---|

| Assessment |

|

| Comprehensive Education |

|

| Provide Written Materials | Reinforce verbal teaching with brochures, pamphlets, or reliable website resources. |

| Encourage Questions | Create an open environment for discussion. |

| Family Involvement | Include family members or caregivers in education as appropriate. |

| Action | Detail/Rationale |

|---|---|

| Assessment |

|

| Early Detection | Educate patient on symptoms to report immediately (e.g., new weakness, numbness, severe radiating pain). |

| Positioning | Assist with positioning to avoid pressure on nerves. |

| Referral | Promptly notify the healthcare provider if neurovascular changes are noted, as surgical intervention may be required. |

It’s good

Thank you

Thanks

Easily understandable