Table of Contents

ToggleChild Growth and Development

Growth is the process of physical increase in size, such as height and weight. It is a quantitative measure that also includes the maturation of body systems.

Development is the progressive increase in skill and capacity to function. It is a qualitative measure that results from the maturation and myelination of the nervous system, allowing for more complex body structures and functions.

Patterns of Growth and Development

Growth and development are orderly, predictable, and follow directional patterns.

- In fetal development, the head grows fastest initially, followed by the trunk, and then the legs.

- At birth, the head is proportionately larger than the rest of the body. As the child matures, the legs grow significantly, increasing from about 38% to 50% of total body length by adulthood.

- An infant gains control of their head before they can sit, and can sit before they can walk.

- In the respiratory system, the trachea develops first, followed by the branching of bronchi, bronchioles, and finally the alveoli.

- Motor control of the arms develops before control of the hands, and hand control is established before fine finger control (pincer grasp).

Critical or Sensitive Periods

These are specific times during development when a child is most receptive to learning a particular skill or behavior, such as walking or language acquisition. Environmental influences, whether positive or negative, have the greatest impact during these periods. Factors like injury, illness, or malnutrition can interfere with development during these critical times.

Factors Influencing Growth and Development

- Prenatal: The mother's health during pregnancy is crucial. Factors like maternal nutrition, smoking, alcohol use, drug exposure, and infections (e.g., rubella) can lead to congenital abnormalities and developmental delays.

- Postnatal: After birth, factors like socioeconomic status, family relationships, housing, access to healthcare, and exposure to environmental hazards influence the child's development.

Factors Contributing to Effective vs. Poor Growth

Factors for Effective Growth (Thriving)

- Exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months, continuing for up to 2 years or more: Breast milk provides optimal nutrition, antibodies for immunity, and promotes healthy bonding. Continued breastfeeding alongside solids extends these benefits.

- Timely introduction of appropriate complementary foods (quality and quantity) at 6 months: Around 6 months, breast milk alone isn't sufficient. Introducing nutrient-dense, varied complementary foods in adequate amounts supports increasing energy and nutrient needs.

- A regular, balanced diet containing all essential nutrients: Ensuring consistent access to a diverse diet rich in carbohydrates, proteins, fats, vitamins, and minerals is fundamental for sustained physical and cognitive development.

- Prevention of childhood illnesses through full immunization and proper sanitation: Vaccinations protect against debilitating diseases, while good hygiene and sanitation reduce exposure to infections that can hinder growth by increasing nutrient demands or reducing appetite.

- Early diagnosis and effective treatment of common illnesses like malaria, diarrhea, and respiratory infections: Prompt and correct medical intervention prevents illnesses from becoming chronic or severe, which can significantly deplete a child's nutritional reserves and impair growth.

- Adequate birth spacing through family planning services: Longer intervals between births allow the mother's body to recover nutritionally and emotionally, enabling her to dedicate more resources and attention to each child's care and development.

- Parental involvement in growth monitoring and health education: Active participation in regular growth monitoring helps identify deviations early, and parental education on nutrition, hygiene, and developmental milestones empowers them to make informed decisions for their child's well-being.

- Responsive feeding practices: Parents or caregivers respond to a child's hunger and fullness cues, offering food in an encouraging and supportive manner without force-feeding or restricting. This builds a healthy relationship with food.

- Secure attachment and stimulating environment: Emotional security from consistent, loving care fosters psychological well-being, which indirectly supports physical health. A stimulating environment (play, interaction, learning) supports cognitive development that is intertwined with physical growth.

- Access to clean water: Essential for hydration and preventing waterborne diseases, which can significantly impact a child's health and ability to absorb nutrients.

Factors for Poor Growth (Failure to Thrive)

- Low birth weight or prematurity: Infants born too small or too early often start life at a disadvantage, with underdeveloped organs and lower nutrient reserves, making them more susceptible to growth faltering.

- Unsuccessful breastfeeding (e.g., poor positioning or attachment): Ineffective breastfeeding leads to inadequate milk intake, poor weight gain, and can discourage mothers, leading to early cessation.

- Early introduction of complementary feeds (before 6 months) or early cessation of breastfeeding: Introducing solids too early can displace nutrient-dense breast milk, increase infection risk, and overwhelm an immature digestive system. Stopping breastfeeding too soon removes a vital source of nutrition and immunity.

- Frequent or chronic illness (e.g., diarrhea, worm infestations, malaria, URTI): Repeated infections increase metabolic demands, reduce appetite, impair nutrient absorption, and lead to nutrient loss, creating a vicious cycle of illness and malnutrition.

- Late introduction of solid foods: Delaying the introduction of complementary foods beyond 6 months means a child's increasing nutritional needs are not met, leading to energy and nutrient deficiencies.

- Poor socioeconomic status leading to food insecurity: Limited financial resources often translate to insufficient access to diverse, nutritious foods, safe water, and adequate healthcare, directly impacting a child's growth.

- Parental ignorance or lack of education about proper nutrition and feeding practices: Lack of knowledge regarding appropriate food choices, preparation, and feeding techniques can lead to inadequate dietary intake and malnourishment, even if food is available.

- Poor maternal health or death of a parent: A mother's ill health (physical or mental) or the absence of a primary caregiver can severely compromise the quality of care, feeding, and emotional support a child receives, impacting their growth.

- Unresponsive feeding practices: Caregivers who ignore a child's hunger cues, force-feed, or provide limited food choices can create negative associations with eating, leading to reduced intake and poor growth.

- Unsanitary living conditions and lack of access to clean water: Exposure to pathogens due to poor hygiene and contaminated water sources increases the risk of recurrent infections, particularly diarrheal diseases, which are major contributors to growth faltering.

- Child neglect or abuse: In severe cases, a lack of adequate physical care, nutritional provision, and emotional support due to neglect or abuse can directly result in severe growth failure and developmental delays.

Stages of Growth and Development

1. Neonatal Period (Birth to 1 Month)

- Weight: Average birth weight is 2.5 to 4.3 kg. A newborn typically loses 5-10% of their birth weight in the first 3-4 days, which should be regained by 10-14 days of age.

- Head: The anterior fontanelle is diamond-shaped, and the posterior is triangular; both are palpable. The head is large, and neck muscles are weak, requiring head support.

- Reflexes: Primitive reflexes like sucking, rooting, grasping, and the startle (Moro) reflex are present and are key indicators of neurological function.

- Physical Characteristics: Skin color varies with ethnicity; blood vessels may be visible. Mongolian spots (bluish discolorations on the lower back/buttocks) are common in dark-skinned infants and fade over time. Breast engorgement or vaginal discharge/bleeding can occur in both sexes due to maternal hormones. Testes should be descended into the scrotum in males.

- Behavior: Sleeps 18-20 hours a day. Can lift head briefly when in a prone position.

- Vital Signs:

- Pulse: 120-160 bpm

- Respirations: 30-50 breaths/min

- Blood Pressure: 50-100 / 20-60 mmHg

- Temperature: 36.5 - 37.5°C

2. Infancy (1 Month to 1 Year)

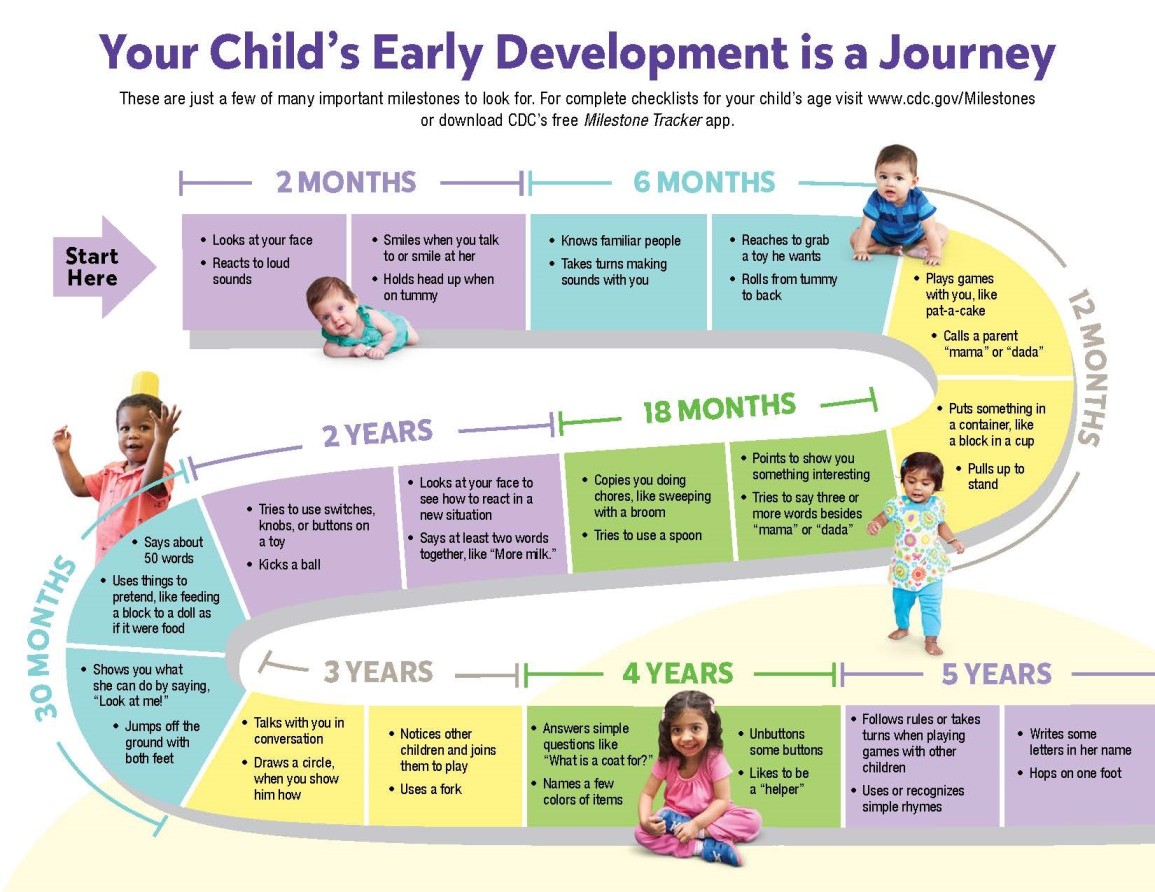

- Growth: Rapid growth period. Weight doubles by 5-6 months and triples by 1 year.

- Social Development: Exhibits a real social smile by 2 months. Begins to interact and gurgle by 3 months. Stranger anxiety often develops around 8 months.

- Motor Skills: Persistence of neonatal reflexes beyond 4 months may indicate an abnormality. Rolls from back to side by 4 months. Bears weight on legs by 6-7 months. Sits alone by 7 months. Pulls to a stand by 9-10 months. Walks with assistance or alone by 12 months. Grasp reflex is replaced by voluntary pincer grasp by 9-11 months.

- Dentition & Diet: First teeth typically erupt around 6 months; should have 6-8 teeth by 1 year. Solid foods are introduced around 6 months.

- Vital Signs:

- Pulse: 80-180 bpm

- Respirations: 30 breaths/min

- Blood Pressure: 74-100 / 50-70 mmHg

- Temperature: 36.5 - 37.2°C

3. Toddlerhood (1 to 3 Years)

- Behavior: Characterized by exploration, autonomy, and negativism ("no"). Has the strength and will to resist. Suspect hearing impairment if speech is not clear by age 2.

- Growth: Growth rate slows. Gains a "pot-bellied" appearance. Head circumference increases about 1 inch between ages 1 and 2. Brain growth reaches about 80% of adult size by age 3.

- Dentition: Primary dentition (20 teeth) is complete by 30 months.

- Motor Skills: Improved coordination and equilibrium. Develops sphincter control, making toilet training possible (usually between 18-24 months).

- Cognitive: Rapid increase in language skills.

- Vital Signs:

- Pulse: 80-140 bpm

- Respirations: 25 breaths/min

- Blood Pressure: 80-112 / 50-80 mmHg

- Temperature: 36.0 - 37.2°C

4. Preschool (3 to 6 Years)

- Behavior: Generally cooperative and likes to please; responds well to praise. Engages in interactive and imaginative play.

- Growth: Physical growth continues to slow. The pot-bellied appearance diminishes by age 5.

- Motor Skills: Skills become more refined; can ride a tricycle, hop, and draw simple shapes.

- Health: Prone to skin infections and lice due to close interactive play. Dental visits should begin.

- Vital Signs:

- Pulse: 80-120 bpm

- Respirations: 23-30 breaths/min

- Blood Pressure: 80-110 / 50-70 mmHg

- Temperature: 36.3 - 37.0°C

5. Middle Childhood / School Age (6 to 12 Years)

- Behavior: Capable of following instructions and using age-appropriate language. Privacy becomes important.

- Growth & Physical Changes: First permanent teeth (molars) appear at age 6. Respirations become thoracic by age 7. In girls, breast budding may begin around 9 years.

- Cognitive: Thinking becomes more logical. Articulation should be correct by age 7.

- Vital Signs:

- Pulse: 70-115 bpm

- Respirations: 17-20 breaths/min

- Blood Pressure: 84-120 / 54-80 mmHg

- Temperature: 36.5 - 36.8°C

6. Adolescence (13 to 19 Years)

- Behavior: Seeks independence; may not want caregivers present during examinations. Direct questions to the adolescent. Peer group is highly influential.

- Physical Changes (Puberty): Development of secondary sexual characteristics. In girls, breasts enlarge and menstruation begins. In boys, testes enlarge and voice deepens. Pubic and axillary hair develops in both sexes.

- Vital Signs:

- Pulse: 50-100 bpm

- Respirations: 16-18 breaths/min

- Blood Pressure: 94-140 / 62-88 mmHg

- Temperature: 36.6°C

Theories of Growth and Development

Theories provide frameworks for understanding human behavior. Key theorists in child development include Erikson (psychosocial), Freud (psychosexual), Piaget (cognitive), and Kohlberg (moral).

Erikson's Theory of Psychosocial Development

Erikson described development as a series of psychosocial crises that must be resolved at each stage for healthy personality development.

Infancy (Birth-1 year): Basic Trust vs. Mistrust

The central task is to establish trust. When caregivers consistently meet the infant's needs for food, comfort, and affection, the infant learns to trust the world as a safe place. Failure to do so leads to mistrust, which can hinder future relationships.

Example: A baby who is consistently fed when hungry and comforted when crying learns to trust their caregivers and the world around them. Conversely, a baby whose needs are inconsistently met may develop a sense of mistrust, becoming anxious or withdrawn.

Toddlerhood (1-3 years): Autonomy vs. Shame and Doubt

The child must establish a sense of autonomy (self-governance). As they learn to walk, talk, and do things for themselves, they develop self-confidence. If they are overly criticized or controlled, they may develop a sense of shame and doubt in their own abilities.

Example: A toddler who is encouraged to choose their own clothes and pour their own juice (even if some spills) develops a sense of autonomy. If caregivers are overly critical or controlling, the toddler might feel shame and doubt about their abilities, becoming hesitant to try new things.

Preschool (3-6 years): Initiative vs. Guilt

The central task is to develop a sense of initiative. Children begin to plan activities, make up games, and initiate activities with others. If this initiative is encouraged, they develop a sense of purpose. If it is discouraged or seen as a nuisance, they may develop a sense of guilt.

Example: A preschooler who enthusiastically proposes a game of "hide-and-seek" and organizes their friends to play is demonstrating initiative. If their attempts to initiate play are constantly dismissed or criticized, they might develop guilt over their desires and become less proactive.

School Age (6-12 years): Industry vs. Inferiority

The focus is on developing a sense of industry. Children learn to be productive and master new skills in school and social settings. Success leads to a sense of competence, while repeated failure can lead to feelings of inferiority and inadequacy.

Example: A school-aged child who diligently works on a science project and feels proud of their completed work is developing industry. If they consistently struggle in school despite effort or are told they are "not good enough," they may develop feelings of inferiority.

Adolescence (12-19 years): Identity vs. Role Confusion

The central task is to develop a stable sense of identity (who they are and where they are going). Adolescents explore different roles, values, and beliefs. Success leads to a consistent sense of self. Failure results in role confusion and a weak sense of self.

Example: An adolescent who tries out for various sports teams, joins different clubs, and explores different academic subjects to discover their interests is forming their identity. Conversely, an adolescent who struggles to find their place, drifts between different social groups without a strong sense of belonging, or adopts an identity without personal reflection, may experience role confusion.

Freud's Theory of Psychosexual Development

Freud's theory centers on the idea that personality develops through a series of stages where pleasure-seeking energies (libido) are focused on different erogenous zones.

Oral Stage (Birth-18 months)

The focus of pleasure is the mouth (sucking, biting, chewing). This provides not only nourishment but also psychological comfort. Fixation at this stage could lead to behaviors like nail-biting, smoking, or overeating in adulthood.

Example: A baby putting everything in their mouth to explore their environment and soothe themselves is typical of the oral stage. An adult who constantly chews on pens or overeats when stressed might be experiencing an oral fixation.

Anal Stage (18 months-3 years)

The focus of pleasure shifts to the anus and the processes of elimination. This stage is associated with toilet training, where the child learns control. Fixation can lead to personalities that are overly orderly (anal-retentive) or messy (anal-expulsive).

Example: A toddler who insists on using the potty themselves and is very proud of their ability to control their bladder and bowels is demonstrating control related to the anal stage. An adult with an anal-retentive personality might be excessively neat, punctual, and controlling, while an anal-expulsive person might be messy and disorganized.

Phallic Stage (3-6 years)

The focus of pleasure is the genitalia. During this stage, children become aware of gender differences and may develop complexes (Oedipus/Electra). Fixation can lead to issues with sexuality and gender identity.

Example: A young boy expressing a strong attachment to his mother and showing some jealousy towards his father, characteristic of the Oedipus complex. Fixation could manifest in adulthood as vanity, exhibitionism, or difficulty with intimate relationships.

Latency Stage (6 years-Puberty)

Sexual urges are repressed, and energy is channeled into social and intellectual pursuits like school, sports, and friendships with same-sex peers.

Example: A child focusing on developing friendships, excelling in school, and participating in extracurricular activities, with little overt interest in romantic relationships. This period allows for the development of social skills and learning.

Genital Stage (Puberty Onward)

Sexual energy reawakens and is directed towards mature, heterosexual relationships. The focus of pleasure is on sexual intercourse and forming intimate relationships.

Example: An adolescent beginning to explore romantic relationships and developing a sense of attraction towards others, leading to the formation of mature, loving relationships.

Piaget's Theory of Cognitive Development

Piaget's theory explains how a child's thinking and intelligence progress through distinct stages.

Sensorimotor Period (Birth-2 years)

Infants learn about the world through their senses and motor actions. A key achievement is object permanence—the understanding that objects continue to exist even when they cannot be seen. Thinking is egocentric.

Example: A baby crying when a toy is hidden under a blanket, then pulling the blanket away to find it, demonstrates developing object permanence. Prior to this, if the toy is out of sight, it's out of mind.

Preoperational Period (2-7 years)

Children use language and symbols, but thinking is illogical and still egocentric. They engage in magical thinking (believing their thoughts can cause events) and animism (attributing life to inanimate objects). They cannot yet grasp the concept of conservation (e.g., that a quantity of liquid remains the same in a differently shaped glass).

Example: A child believing their doll feels sad when it falls (animism), or insisting that a tall, narrow glass has more juice than a short, wide one, even if both contain the same amount (lack of conservation). They might also cover their eyes and think if they can't see you, you can't see them (egocentrism).

Concrete Operational Period (7-11 years)

Thinking becomes more logical and organized, but it is still concrete (tied to physical reality). They can understand conservation, reversibility, and can see things from another's point of view. They can reason about concrete events but struggle with abstract concepts.

Example: A child understanding that if you pour water from a tall, thin glass into a short, wide glass, the amount of water remains the same (conservation). They can also sort objects by multiple features, but might struggle with hypothetical questions like "What if humans had wings?"

Formal Operational Period (11 years Onward)

Adolescents develop the ability to think abstractly, reason hypothetically, and use deductive logic. They can consider multiple possibilities and think about moral, philosophical, and social issues.

Example: A teenager debating complex social issues like climate change or justice, considering different perspectives and hypothetical scenarios, or planning a multi-step project by thinking through all possible outcomes.

Kohlberg's Theory of Moral Development

Kohlberg's theory focuses on the development of moral reasoning, or how people think about right and wrong.

Level 1: Preconventional Morality (Toddler to School Age)

Morality is externally controlled. Rules are obeyed to avoid punishment or receive rewards.

- Stage 1: Obedience and Punishment Orientation. Behavior is judged as wrong if it is punished.

- Stage 2: Individualism and Exchange. "What's in it for me?" orientation. Right behavior is what is in one's own best interest.

Example: A child not stealing a cookie because they know they will get a time-out if caught, or a child refraining from hitting another child solely to avoid being punished by a parent.

Example: A child sharing their toy with another child because they expect the other child to share their toy in return, or a child offering to help with chores only if they get paid.

Level 2: Conventional Morality (School Age to Adolescence)

Conformity to social rules is important, but not for self-interest. The focus is on maintaining social order and positive relationships.

- Stage 3: Good Interpersonal Relationships. The "good boy/good girl" orientation. Right behavior is what pleases or is approved of by others.

- Stage 4: Maintaining the Social Order. Right behavior consists of doing one's duty, showing respect for authority, and maintaining the given social order.

Example: A student following classroom rules because they want to be seen as a "good student" by their teacher and peers, or a teenager refraining from cheating because they want their friends to see them as honest.

Example: A citizen paying their taxes because they understand it is their duty to uphold the laws of their country and maintain societal order, or a driver obeying traffic laws because it is the rule and necessary for public safety.

Level 3: Postconventional Morality (Adolescence and Adulthood)

Morality is defined in terms of abstract principles and values that apply to all situations and societies.

- Stage 5: Social Contract and Individual Rights. Right is determined by socially agreed-upon standards of individual rights.

- Stage 6: Universal Principles. Right is determined by self-chosen ethical principles of conscience, which are abstract and universal (e.g., justice, equality).

Example: An individual advocating for changes to a law they believe is unfair, even if it is currently legal, because it violates fundamental human rights and the societal contract for justice, such as protesting against discriminatory policies.

Example: An activist dedicating their life to fighting for human rights globally, even in the face of personal risk or legal consequences, because they believe in the universal principle of justice for all, like a civil rights leader who non-violently resists unjust laws based on deep moral convictions.