"Dermatitis" is a broad, umbrella term derived from Greek, where "derma" means skin and "-itis" signifies inflammation. Therefore, dermatitis fundamentally refers to inflammation of the skin.

It is characterized by a reaction pattern of the skin to various internal or external factors, leading to a range of symptoms. While the specific presentation can vary significantly depending on the type and chronicity, common features of dermatitis include:

- Pruritus (Itching): Often the most prominent and distressing symptom.

- Erythema (Redness): Due to increased blood flow to the inflamed area.

- Edema (Swelling): Accumulation of fluid in the tissue.

- Papules and Vesicles: Small, raised bumps and fluid-filled blisters, especially in acute phases.

- Scaling: Flaking of the skin, often in chronic phases.

- Crusting: Dried exudate from ruptured vesicles or erosions.

- Lichenification: Thickening and accentuation of skin lines, occurring with chronic scratching.

- Dryness/Xerosis: Often a prominent feature, particularly in atopic dermatitis.

It's important to note that while "dermatitis" and "eczema" are often used interchangeably, "eczema" specifically refers to a type of dermatitis characterized by inflamed, itchy, and often oozing or scaly skin. Historically, eczema implied an endogenous (internal cause) inflammation, while dermatitis encompassed both endogenous and exogenous (external cause) inflammation. However, in modern clinical practice, atopic dermatitis is the most common form of eczema, and the terms are often synonymous for this condition. For simplicity in this module, we will primarily use "dermatitis" as the overarching term, and specify "atopic dermatitis" when referring to that particular type of eczema.

While many forms of dermatitis exist, we will focus on the most common and clinically significant types:

A chronic, relapsing, inflammatory skin condition characterized by intense pruritus, erythema, scaling, and often lichenification.

- Endogenous: Primarily driven by internal factors (genetics, immune dysfunction, skin barrier defects).

- "The Itch that Rashes": Itching often precedes the visible rash.

- Distribution: Varies with age (e.g., extensor surfaces in infants, flexural creases in children/adults).

- Associated Conditions: Often part of the "atopic triad" (asthma, allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis).

- Skin Barrier Dysfunction: A hallmark feature, leading to increased water loss and susceptibility to irritants/allergens.

An inflammatory skin reaction caused by direct contact with an external substance. It is always an exogenous dermatitis.

- Distribution: Typically localized to the area of contact with the offending substance.

- Two Main Types:

- Irritant Contact Dermatitis (ICD):

- Mechanism: Non-allergic skin reaction to a direct chemical or physical injury from an irritant (e.g., strong acids, alkalis, solvents, detergents, prolonged water exposure).

- Prevalence: Accounts for 80% of contact dermatitis cases.

- Onset: Can occur on first exposure, depending on the irritant's potency.

- Allergic Contact Dermatitis (ACD):

- Mechanism: A delayed-type hypersensitivity (Type IV) reaction to an allergen in a sensitized individual (e.g., poison ivy, nickel, fragrances, preservatives).

- Prevalence: Accounts for 20% of contact dermatitis cases.

- Onset: Requires prior sensitization; reaction develops 24-72 hours after re-exposure.

- Irritant Contact Dermatitis (ICD):

A chronic inflammatory skin condition affecting areas rich in sebaceous glands (where oil is produced).

- Distribution: Scalp (dandruff in adults, cradle cap in infants), face (eyebrows, nasolabial folds, ears), chest, intertriginous areas.

- Appearance: Greasy, yellowish scales on an erythematous base. Itching can be present but is usually less severe than in atopic dermatitis.

- Association: Linked to the yeast Malassezia (formerly Pityrosporum ovale) and often exacerbated by stress, fatigue, or neurological conditions (e.g., Parkinson's disease).

An inflammatory skin condition that develops on the lower legs due to chronic venous insufficiency.

- Distribution: Typically involves the ankles and lower calves.

- Appearance: Erythema, scaling, pruritus, edema, and often hyperpigmentation (hemosiderin staining from extravasated red blood cells, giving a "brawny" or reddish-brown appearance).

- Underlying Cause: Impaired venous return leads to increased pressure in capillaries, fluid leakage, and inflammation.

- Progression: Can progress to ulceration if untreated.

| Feature | Atopic Dermatitis | Contact Dermatitis (Irritant/Allergic) | Seborrheic Dermatitis | Stasis Dermatitis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Cause | Genetic, immune, skin barrier defect | Direct contact with irritant/allergen | Malassezia yeast, sebaceous activity | Venous insufficiency, impaired circulation |

| Nature | Chronic, relapsing, endogenous | Acute/Chronic, exogenous (external) | Chronic, relapsing | Chronic, due to vascular compromise |

| Main Symptom | Intense pruritus ("itch that rashes") | Pruritus, burning, pain | Greasy scaling, mild itch | Pruritus, edema, heaviness in legs |

| Appearance | Erythema, papules, vesicles, scaling, lichenification, dry skin | Erythema, edema, vesicles/bullae, oozing, crusting, sharp borders | Erythema, greasy yellow scales, sometimes oily skin | Erythema, edema, scaling, hyperpigmentation, varicosities |

| Typical Location | Flexural folds (children/adults), face (infants), neck | Area of contact with offending substance | Scalp, face (T-zone), chest, intertriginous areas | Lower legs, ankles |

| Associated Factors | Asthma, allergic rhinitis | Exposure history, occupation | Stress, neurological conditions, immunosuppression | Varicose veins, DVT, heart failure, obesity |

- Dermatitis herpetiformis. Appears as a result of a gastrointestinal condition, known as celiac disease.

- Seborrheic dermatitis. More common in infants and in individuals between 30 and 70 years old. It appears to affect primarily men and it occurs in 85% of people suffering from AIDS.

- Nummular dermatitis. Also known as discoid dermatitis, it is characterized by round or oval-shaped itchy lesions. (The name comes from the Latin word "nummus," which means "coin.")

- Perioral dermatitis. Inflammation of the skin around the mouth.

- Infective dermatitis. Dermatitis secondary to a skin infection.

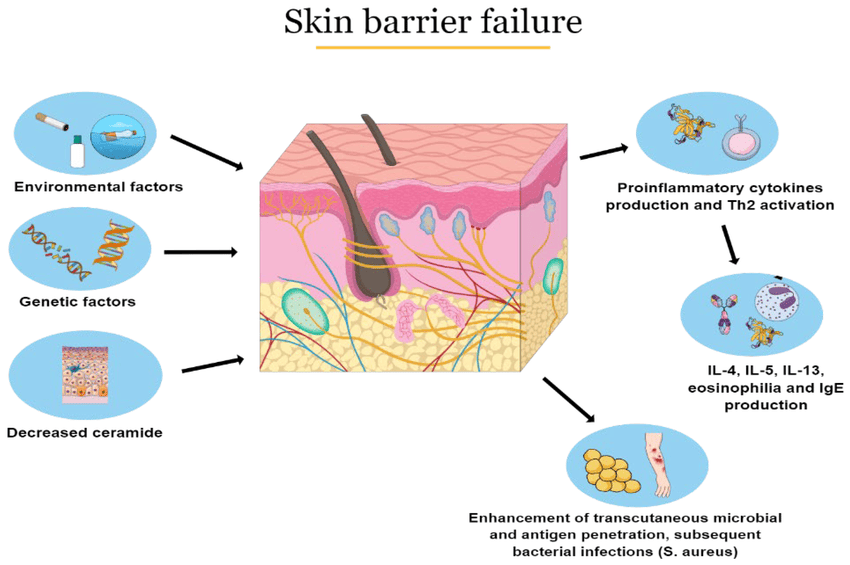

Atopic Dermatitis (AD) is a complex, multifactorial disease involving a vicious cycle of skin barrier dysfunction, immune dysregulation, and environmental factors.

- Skin Barrier Dysfunction (The "Outside-In" Theory):

- Filaggrin Deficiency: A primary defect in many AD patients is a genetic mutation in the FLG gene, which codes for filaggrin. Filaggrin is a protein essential for forming the stratum corneum (outermost layer of the skin) and breaking down into Natural Moisturizing Factors (NMFs).

- Consequence: A deficient or dysfunctional skin barrier (epidermal tight junctions are also affected) leads to:

- Increased Transepidermal Water Loss (TEWL): Skin becomes dry (xerosis), making it more susceptible to external factors.

- Enhanced Penetration: Allows irritants, allergens, and microbes (e.g., Staphylococcus aureus) to easily penetrate the skin barrier.

- Immune Dysregulation (The "Inside-Out" Theory):

- Type 2 Immune Response: AD is predominantly driven by a Type 2 inflammatory response, characterized by the activation of T-helper 2 (Th2) cells.

- Key Cytokines: Th2 cells produce cytokines like Interleukin-4 (IL-4), IL-13, and IL-31.

- IL-4 and IL-13: Promote IgE production by B cells (leading to allergic sensitization), contribute to skin barrier disruption, and stimulate pruritus.

- IL-31: Directly stimulates sensory nerves, causing intense itching.

- Dendritic Cells & Mast Cells: Antigen-presenting cells (dendritic cells/Langerhans cells) in the skin take up allergens that penetrate the compromised barrier and present them to T cells, perpetuating the immune response. Mast cells, when activated, release histamine and other inflammatory mediators, further contributing to itch and inflammation.

- Neural Dysregulation: Sensory nerves in the skin become more sensitive and grow into the epidermis, making the skin more prone to itching.

- Microbiome Alterations (Dysbiosis):

- Staphylococcus aureus: The skin of AD patients is frequently colonized with Staphylococcus aureus. These bacteria produce toxins (superantigens) that further activate the immune system, worsen inflammation, and exacerbate skin barrier damage.

- Reduced Diversity: A decrease in the diversity of beneficial skin microbes may also play a role.

- The "Itch-Scratch Cycle":

- Intense pruritus leads to scratching, which physically damages the skin barrier.

- This damage allows more allergens/irritants/microbes to enter, amplifying the immune response and inflammation.

- Inflammation further stimulates nerve endings, leading to more itching, thus perpetuating the cycle.

Contact dermatitis arises from a direct reaction of the skin to an external substance.

- Non-Immunological Reaction: ICD is a direct toxic damage to keratinocytes (skin cells) and the skin barrier, not involving an allergic immune response.

- Mechanism of Injury:

- Direct Cytotoxicity: Irritants (e.g., strong acids, alkalis, detergents, solvents, excessive water) directly damage cell membranes and proteins in the epidermis.

- Lipid Extraction: Solvents can dissolve the protective lipid layer of the stratum corneum, increasing permeability and water loss.

- Inflammatory Cascade: Damaged keratinocytes release pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-1, TNF-alpha) and chemokines. These recruit inflammatory cells (neutrophils, monocytes, T cells) to the site, leading to erythema, edema, and pain.

- Individual Susceptibility: Factors like genetic predisposition (e.g., pre-existing dry skin, atopic diathesis), skin site (thinner skin areas are more vulnerable), occlusive environments, and concentration/duration of irritant exposure influence the severity of the reaction.

- Triggers: Contact dermatitis is caused by exposure to a substance that irritates your skin or triggers an allergic reaction, such irritants include;

- Soaps. Most kinds of soaps, detergents, shampoos and other cleaning agents have harmful substances that could possibly irritate the skin.

- Solvents. Solvents such as turpentine, kerosene, fuel, and thinners are strong substances that are harmful to the sensitive skin.

- Extremes of temperature. There are people who are highly sensitive even when exposed to extremes of temperature and could cause contact dermatitis.

- Products that cause a reaction when you’re in the sun (photoallergic contact dermatitis), such as some sunscreens and cosmetics

- Formaldehyde, which is in preservatives, cosmetics and other products

- Personal care products, such as body washes, deodorants, hair dyes and cosmetics

- Plants such as poison ivy and poison oak, cashew nuts, which contain a highly allergenic substance called urushiol

- Airborne allergens, such as pollen and spray insecticides

- Nickel, which is used in jewelry, and many other items

- Medications, such as antibiotic creams, and there side effects such as diazepam, ceftriaxone.

- Latex and long exposure to wet surfaces such as staying in a wet diaper for a long time.

- Delayed-Type Hypersensitivity (Type IV) Reaction: ACD is a T-cell mediated immune response that requires prior sensitization to an allergen.

- Sensitization Phase (Initial Exposure - Asymptomatic):

- Hapten Penetration: Small molecular weight chemicals (haptens) that are too small to be antigenic on their own penetrate the skin barrier.

- Protein Binding: Haptens bind covalently to larger skin proteins (often keratinocytes or extracellular matrix proteins), forming a complete antigen (hapten-protein complex).

- Antigen Presentation: Langerhans cells (dendritic cells in the epidermis) capture these hapten-protein complexes, process them, and migrate to regional lymph nodes.

- T-cell Priming: In the lymph nodes, the Langerhans cells present the antigen to naive T-helper cells. These T cells proliferate and differentiate into allergen-specific memory T cells. This phase takes 7-14 days.

- Elicitation/Challenge Phase (Re-exposure - Symptomatic):

- Re-penetration: Upon subsequent re-exposure to the same allergen, it again penetrates the skin.

- Memory T-cell Activation: The memory T cells, having "seen" the allergen before, are rapidly activated.

- Cytokine Release: Activated T cells release a cascade of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IFN-gamma, TNF-alpha, IL-17) and chemokines.

- Inflammatory Cell Recruitment: These mediators attract and activate other inflammatory cells (macrophages, keratinocytes, and more T cells) to the site of allergen contact.

- Tissue Damage: The recruited inflammatory cells and cytokines cause direct damage to keratinocytes and the surrounding tissue, leading to the characteristic clinical manifestations (erythema, edema, vesicles, itching) typically appearing 24-72 hours after re-exposure.

The exact pathophysiology of Seborrheic Dermatitis is not fully understood, but it is believed to involve a combination of factors related to sebaceous gland activity, the skin microbiome, and the host's immune response.

- Role of Malassezia Species:

- Commensal Yeast: Malassezia is a genus of lipophilic (fat-loving) yeasts that are normal inhabitants of human skin, particularly in sebaceous gland-rich areas.

- Immune Response: In SD, there is an abnormal immune response to these yeasts, or an overgrowth of Malassezia, or both. The yeasts break down triglycerides in sebum, releasing unsaturated fatty acids that can be irritating and trigger inflammation.

- Host Susceptibility: Not all individuals with Malassezia develop SD, suggesting host factors (e.g., immune system alterations) play a crucial role.

- Sebaceous Gland Activity:

- Increased Sebum Production: SD occurs in areas with a high density of sebaceous glands (scalp, face, chest). While increased sebum production is often observed, it's not simply an excess of oil; rather, it's the composition of the sebum and its interaction with Malassezia that is important.

- Immune Response:

- Inflammation: The inflammatory response in SD involves keratinocytes, which react to Malassezia metabolites by releasing pro-inflammatory cytokines. This leads to the characteristic erythema and scaling.

- Genetic and Environmental Factors: Genetic predisposition, hormonal changes, stress, fatigue, neurological conditions (e.g., Parkinson's disease), and immunosuppression (e.g., HIV/AIDS) can all exacerbate SD, suggesting a complex interplay with the immune system.

Stasis Dermatitis is a consequence of chronic venous insufficiency (CVI), where impaired venous return leads to a cascade of events in the lower extremities.

- Chronic Venous Insufficiency (CVI):

- Venous Hypertension: Damaged or incompetent venous valves in the leg veins (often following deep vein thrombosis, trauma, or due to genetic predisposition) prevent efficient blood return to the heart. This leads to increased hydrostatic pressure in the veins of the lower legs.

- Capillary Leakage: The sustained high pressure forces fluid, red blood cells, and macromolecules (like fibrinogen) out of the capillaries and into the interstitial space of the dermis.

- Inflammation and Tissue Damage:

- Edema: Leakage of fluid causes chronic swelling (edema) in the lower legs.

- Hemosiderin Deposition: Red blood cells extravasate into the tissue. As they break down, they release iron-containing hemosiderin, which is phagocytosed by macrophages and deposited in the dermis, leading to the characteristic reddish-brown (brawny) hyperpigmentation.

- Fibrin Cuffing: Fibrinogen that leaks into the interstitial space is converted to fibrin, forming "fibrin cuffs" around capillaries. This theoretically impairs oxygen and nutrient delivery to the skin, contributing to tissue hypoxia and damage.

- Inflammatory Cell Infiltration: The chronic inflammation recruits macrophages, lymphocytes, and other inflammatory cells, further damaging the skin.

- Lipodermatosclerosis: In chronic, severe cases, inflammation and fibrosis of the subcutaneous fat can occur, leading to hardening of the skin and a "woody" appearance (often described as an "inverted champagne bottle" appearance).

- Skin Barrier Impairment and Pruritus:

- The chronic inflammation, edema, and poor tissue nutrition impair the skin barrier, leading to dryness, scaling, and intense pruritus.

- Scratching further damages the skin, increasing the risk of secondary infection and ulceration.

Characteristic signs (what the clinician observes) and symptoms (what the patient experiences) of each major type of dermatitis.

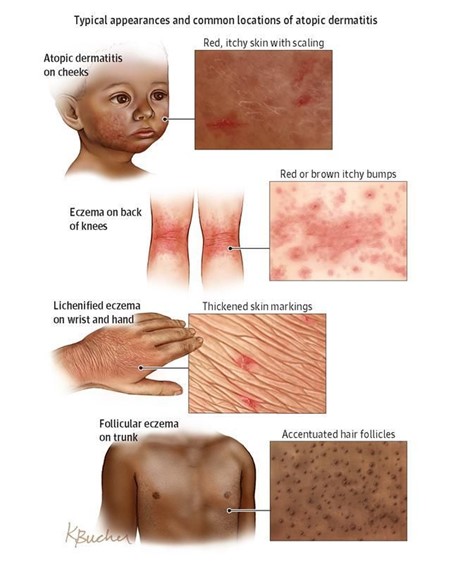

Atopic dermatitis is characterized by intense pruritus and an inflammatory rash that varies in morphology and distribution with age. The key is "the itch that rashes."

- Pruritus (Itching): The cardinal symptom, often severe, leading to scratching and perpetuating the itch-scratch cycle. It can be worse at night, disrupting sleep.

- Xerosis (Dry Skin): Very common, contributing to pruritus and skin barrier dysfunction.

- Erythema: Redness of the affected skin.

- Scaling: Flaking of the skin surface.

- Distribution: Primarily affects the face (cheeks, forehead, scalp), extensor surfaces of the limbs (outer elbows, knees), and trunk. Diaper area is usually spared.

- Appearance: Often acute, presenting with bright red patches, papules (small, raised bumps), vesicles (small, fluid-filled blisters) that may rupture and weep, leading to crusting and oozing. Lesions can be quite edematous (swollen).

- Distribution: Characteristically involves the flexural creases (antecubital fossae - inner elbows, popliteal fossae - behind the knees), wrists, ankles, and neck.

- Appearance: Becomes more chronic. Lesions are often less exudative and more lichenified (thickened, leathery skin with exaggerated skin lines due to chronic rubbing/scratching). Papules and plaques are common. Erythema and scaling persist. Post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation (darkening) or hypopigmentation (lightening) can occur.

- Distribution: Similar to childhood, still commonly affecting flexural areas (antecubital, popliteal, neck, eyelids, hands, feet). Can also be more widespread or localized to hands/feet (pompholyx/dyshidrotic eczema), eyelids, or nipples.

- Appearance: Highly variable. Often chronic, lichenified plaques dominate. Nodules (prurigo nodularis) can develop from intense scratching. Erythema and scaling are present. Exacerbations can lead to more acute, vesicular lesions. Significant psychosocial impact is common.

- Dennie-Morgan Folds: Extra fold of skin below the eye.

- Allergic Shiners: Dark circles under the eyes.

- Facial Pallor: Paleness around the mouth.

- Pityriasis Alba: Hypopigmented (lighter) patches, especially on the face and upper arms after sun exposure.

- Ichthyosis Vulgaris: Genetic condition causing dry, scaly skin, often associated with AD.

- Hyperlinear Palms: Increased number of lines on the palms.

Contact dermatitis presents as an itchy, erythematous rash that occurs where the skin has come into contact with an irritant or allergen. The pattern often provides a clue.

- Acute: Erythema, edema, vesicles, bullae (large blisters), oozing, and crusting.

- Chronic: Scaling, lichenification, fissuring (cracks in the skin), and sometimes hyperpigmentation.

- Acute: Erythematous, edematous patches and plaques, often with numerous vesicles and bullae, sometimes linearly arranged (e.g., from poison ivy). Oozing and crusting are common.

- Chronic: Dryness, scaling, lichenification, and fissuring.

Seborrheic dermatitis is characterized by greasy, yellowish scales on an erythematous base, typically in sebaceous gland-rich areas.

- Erythematous Patches/Plaques: Red skin.

- Greasy Yellowish Scales: Characteristic appearance, sometimes with crusting.

- Well-demarcated: Lesions often have distinct borders.

- Scalp: Most common site. Presents as dandruff (fine, white, loose scales) in adults. In infants, it's known as cradle cap (thick, oily, yellowish scales, sometimes matted to hair).

- Face: Common in eyebrows, glabella (between eyebrows), nasolabial folds (sides of nose), retroauricular area (behind ears), external ear canal.

- Trunk: Sternum (central chest), interscapular area (between shoulder blades).

- Intertriginous Areas: Skin folds (axillae, groin, inframammary folds), especially in obese or immunosuppressed individuals.

Stasis dermatitis primarily affects the lower legs and is a consequence of chronic venous insufficiency.

- Edema: Swelling of the lower legs and ankles, often pitting.

- Erythema: Redness, especially around the ankles and lower calves.

- Scaling and Crusting: Due to inflammation and dryness.

- Hyperpigmentation: Characteristic reddish-brown discoloration due to hemosiderin deposition (often described as "brawny" edema).

- Varicose Veins: May be visible, indicating underlying venous insufficiency.

- Atrophie Blanche: Scar-like, porcelain-white areas surrounded by telangiectasias (spider veins) and hyperpigmentation, indicating skin damage and poor healing.

- Lichenification: Can develop from chronic scratching.

- Ulceration: In advanced or neglected cases, particularly around the medial malleolus (inner ankle bone), due to poor circulation and minor trauma. These are typically shallow, irregular, and exudative.

| Feature | Atopic Dermatitis | Contact Dermatitis (Irritant/Allergic) | Seborrheic Dermatitis | Stasis Dermatitis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pruritus | Intense, often nocturnal | Intense (ACD) to mild/burning (ICD) | Mild to moderate | Moderate to severe, associated with heaviness |

| Appearance | Erythema, papules, vesicles, oozing, crusting, lichenification, xerosis | Erythema, edema, vesicles, bullae, oozing, crusting, sharp borders (ACD) | Erythema, greasy yellowish scales, well-demarcated | Erythema, edema, brawny hyperpigmentation, scaling, ulcers |

| Typical Location | Face, extensors (infants); flexural folds (children/adults) | Area of contact with offending agent | Scalp (dandruff/cradle cap), face (T-zone), chest, folds | Lower legs, ankles |

| Chronicity | Chronic, relapsing | Acute to chronic, depending on exposure | Chronic, relapsing | Chronic, progressive |

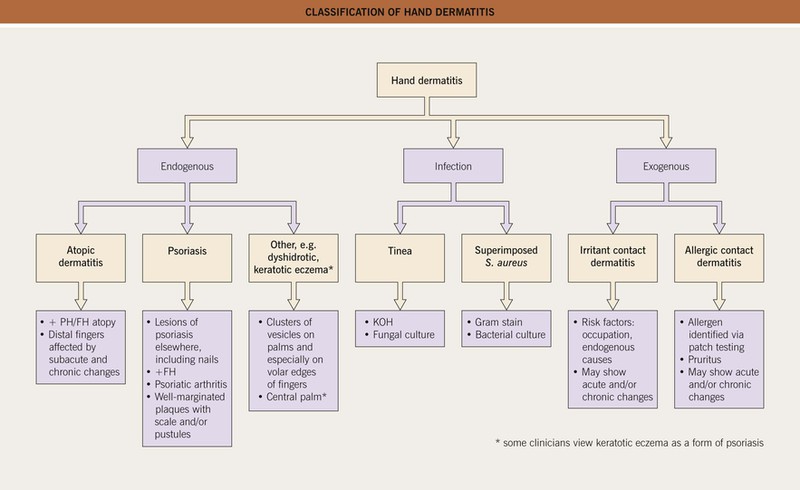

Diagnosis of dermatitis primarily relies on a comprehensive clinical history and physical examination.

- Onset and Duration: When did the rash start? Is it acute or chronic? Intermittent or continuous?

- Symptom Characterization: Detailed description of pruritus (severity, timing, aggravating/alleviating factors), pain, burning, stinging.

- Distribution and Evolution: Where did it start? How has it spread or changed over time?

- Aggravating/Alleviating Factors: What makes it worse or better (e.g., stress, weather, specific activities, products)?

- Personal and Family History:

- Atopic History: Personal or family history of asthma, allergic rhinitis, food allergies (critical for AD).

- Occupational/Hobby Exposure: Detailed review of work, hobbies, personal care products, clothing, jewelry (critical for CD).

- Medical Comorbidities: Neurological conditions (Parkinson's), HIV/AIDS (for SD); history of DVT, varicose veins, heart failure (for Stasis Dermatitis).

- Medications: Current prescription and over-the-counter medications, including topical preparations.

- Previous Treatments: What has been tried, and what was the response?

- General Skin Assessment: Note overall skin type (dry, oily), signs of xerosis.

- Morphology of Lesions: Identify primary (macules, papules, vesicles, bullae) and secondary (scales, crusts, erosions, excoriations, lichenification, fissures) lesions.

- Distribution and Configuration: Is it generalized or localized? Symmetrical or asymmetrical? Are there patterns suggestive of contact (e.g., linear, geometric)? Are flexural or extensor surfaces involved?

- Severity Assessment: Tools like Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) for AD, or subjective assessment of erythema, edema, excoriation, and lichenification.

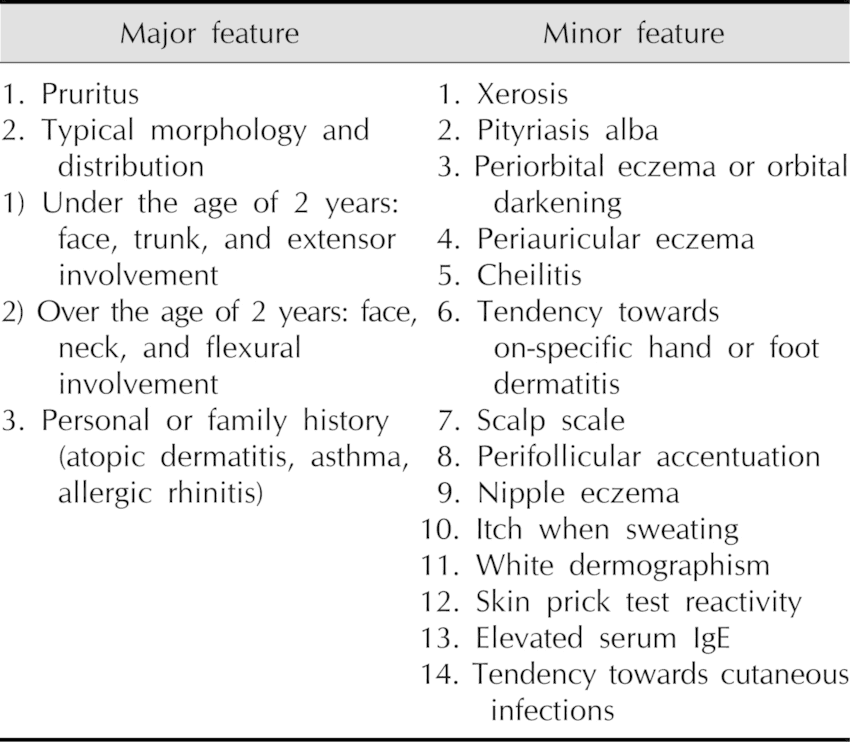

- Major Criteria (Hanifin and Rajka):

- Pruritus

- Typical morphology and distribution (flexural lichenification/linearity in adults; facial/extensor involvement in infants/children)

- Chronic or chronically relapsing dermatitis

- Personal or family history of atopy (asthma, allergic rhinitis, AD)

- Minor Criteria: Include early age of onset, xerosis, ichthyosis, hyperlinear palms, elevated serum IgE, recurrent conjunctivitis, periorbital darkening, Dennie-Morgan folds, facial pallor/erythema, white dermatographism, anterior neck folds, food intolerance, skin infections, wool intolerance, and perifollicular accentuation. (Diagnosis requires 3 major + 3 minor criteria).

- Serum IgE Levels: Often elevated, but not specific for AD and not required for diagnosis.

- Allergen-Specific IgE (RAST/ImmunoCAP) or Skin Prick Tests: Can identify specific aeroallergens or food allergens in sensitized individuals, which may be contributing to flares. However, a positive test does not automatically mean the allergen is a trigger for the skin condition.

- Skin Biopsy: Rarely needed for typical AD. May be considered if diagnosis is uncertain or to rule out other conditions (e.g., cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, psoriasis). Histology shows spongiosis (epidermal edema), exocytosis of lymphocytes, and chronic inflammatory infiltrate.

- Bacterial/Viral Swabs: To check for secondary infections (e.g., Staphylococcus aureus, Herpes Simplex Virus) if exudative lesions or atypical presentations are noted.

- Gold Standard for ACD.

- Procedure: Small amounts of suspected allergens are applied to the skin (usually the back) under occlusive patches for 48 hours. The patches are removed, and the site is evaluated at 48 hours and again at 72 or 96 hours for a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction (erythema, papules, vesicles).

- Purpose: To identify the specific allergen(s) causing the reaction, which is crucial for avoidance strategies.

- Timing: Should be performed when the dermatitis is quiescent or mild, as severe inflammation can lead to false positives (irritant reactions) or false negatives.

- Diagnosis is primarily clinical, based on the characteristic appearance and distribution of lesions.

- No specific diagnostic tests are routinely performed.

- Skin Scraping/Culture: May be considered if there's suspicion of secondary bacterial or fungal infection, or if the presentation is atypical (e.g., to rule out tinea capitis in the scalp).

- Biopsy: Rarely indicated. Histology shows superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, spongiosis, and parakeratosis.

- Duplex Ultrasound: Non-invasive imaging to visualize leg veins, assess valve function, and identify reflux or obstruction (e.g., post-thrombotic changes). This is often recommended to guide management.

- The primary goals of dermatitis management are to reduce inflammation, alleviate pruritus, prevent flares, manage complications, and improve the patient's quality of life.

- Patient Education: Crucial for all types of dermatitis. Patients need to understand their condition, its chronic nature (for AD, SD, Stasis), identify their triggers, and adhere to treatment plans.

- Skin Barrier Care: Emphasize regular moisturization, gentle cleansing, and avoidance of harsh soaps/irritants to support skin barrier function.

- Pruritus Control: Addressing itch is paramount to break the itch-scratch cycle and prevent exacerbations.

- Infection Management: Prompt recognition and treatment of secondary bacterial, fungal, or viral infections.

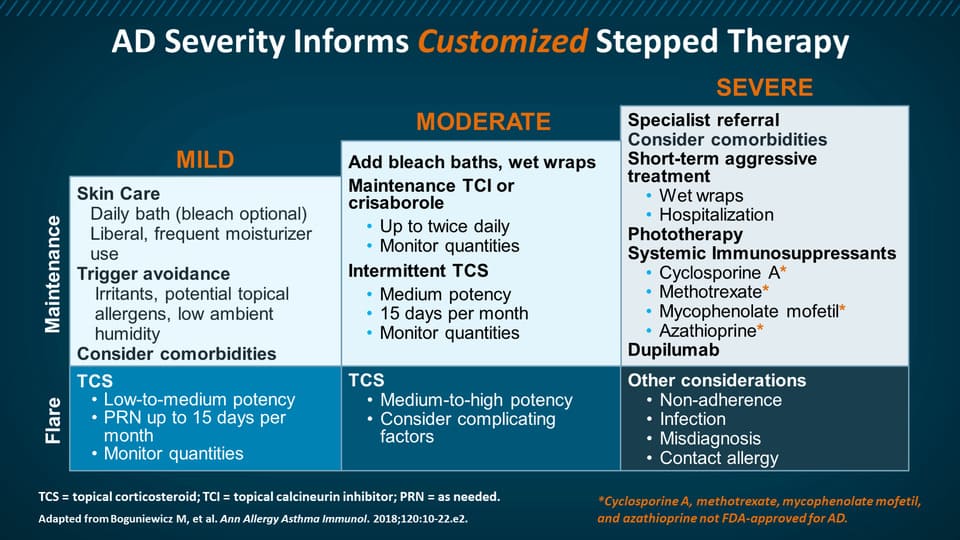

Management of AD is multi-faceted, focusing on skin barrier restoration, inflammation control, and trigger avoidance.

- Emollients/Moisturizers: Daily, liberal application (at least twice daily) of thick creams or ointments (e.g., petroleum jelly, ceramide-containing products) is foundational. Apply within minutes of bathing to "trap" moisture.

- Gentle Cleansing: Short, lukewarm baths/showers with mild, fragrance-free cleansers. Avoid harsh soaps and excessive scrubbing.

- Wet Wraps: Can be highly effective for severe flares, providing intense moisturization and anti-inflammatory effects.

- Topical Corticosteroids (TCS): First-line therapy for flares. Available in varying potencies (low, medium, high, super high). Potency and duration depend on severity, location (avoid high potency on face/intertriginous areas), and patient age. Used to reduce inflammation and pruritus.

- Topical Calcineurin Inhibitors (TCIs): (e.g., tacrolimus, pimecrolimus). Non-steroidal alternatives, particularly useful for sensitive areas (face, intertriginous zones) and for long-term maintenance/flare prevention (proactive therapy).

- Topical PDE4 Inhibitors: (e.g., crisaborole). Newer non-steroidal option for mild-to-moderate AD.

- Topical JAK Inhibitors: (e.g., ruxolitinib). Newer non-steroidal option for short-term and non-continuous chronic treatment of mild-to-moderate AD.

- Phototherapy: (e.g., narrowband UVB). Can be effective for widespread AD.

- Systemic Immunosuppressants: (e.g., cyclosporine, methotrexate, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil). Used for severe, refractory AD, often as a bridge to biologics. Require close monitoring for side effects.

- Biologic Agents: (e.g., dupilumab, tralokinumab, lebrikizumab). Monoclonal antibodies targeting key cytokines (IL-4, IL-13) involved in AD pathogenesis. Highly effective for moderate-to-severe AD.

- Oral JAK Inhibitors: (e.g., upadacitinib, abrocitinib). Oral medications targeting Janus kinase pathways. Also highly effective for moderate-to-severe AD.

- Oral Antihistamines (sedating): (e.g., hydroxyzine, diphenhydramine). Can help with nocturnal pruritus and sleep, but primarily due to sedation, not direct anti-itch effect on AD. Non-sedating antihistamines are generally not effective for AD itch.

- Antipruritic Creams/Lotions: (e.g., menthol, pramoxine).

- Topical Antibiotics: For localized secondary bacterial infection (e.g., mupirocin).

- Systemic Antibiotics: For widespread or severe bacterial infections.

- Antiviral Agents: (e.g., acyclovir) for eczema herpeticum.

- Dilute Bleach Baths: Can reduce S. aureus colonization and inflammation.

The cornerstone of CD management is identifying and avoiding the causative irritant or allergen.

- Irritant Contact Dermatitis (ICD): Educate on the irritant(s) and provide advice on protective measures (e.g., gloves, barrier creams, gentle skin care).

- Allergic Contact Dermatitis (ACD): After patch testing, provide a detailed list of identified allergens and cross-reacting substances. Emphasize complete avoidance. Referral to an occupational therapist for workplace adjustments may be necessary.

- Oral antihistamines (sedating) for itch and sleep.

- Topical pramoxine or menthol for symptomatic relief.

Management aims to control Malassezia overgrowth and reduce inflammation.

- Topical Antifungals:

- Shampoos/Creams: (e.g., ketoconazole, selenium sulfide, zinc pyrithione, ciclopirox). Used regularly (e.g., 2-3 times/week) initially, then for maintenance.

- Mechanism: Reduce Malassezia population.

- Topical Corticosteroids (TCS): Low-potency TCS (e.g., desonide, hydrocortisone) for short durations to reduce inflammation and erythema on the face and sensitive areas.

- Topical Calcineurin Inhibitors (TCIs): (e.g., tacrolimus, pimecrolimus). Non-steroidal alternatives for facial SD, particularly for long-term use to avoid corticosteroid side effects.

- Keratolytics: Salicylic acid or urea preparations can help remove thick scales on the scalp or other areas.

- Systemic Therapies: Rarely needed. Oral antifungals (e.g., fluconazole, itraconazole) may be considered for severe, widespread, or refractory cases, especially in immunocompromised individuals.

- Cradle Cap (Infantile SD):

- Gentle scrubbing with a soft brush and baby shampoo to loosen scales.

- Mineral oil or baby oil applied before shampooing can help soften scales.

- Topical low-potency corticosteroids or antifungal creams (e.g., ketoconazole) for persistent cases.

- Compression Therapy:

- Cornerstone of treatment. Graduated compression stockings (20-30 mmHg or higher) are essential to reduce venous hypertension and edema. Must be worn daily.

- Bandages: For acute flares or ulceration, compression bandages are used.

- Leg Elevation: Regular elevation of the legs above heart level, especially when resting, to promote venous return.

- Exercise: Regular walking and calf muscle exercises to improve the calf muscle pump function.

- Topical Corticosteroids (TCS): Medium-potency TCS for short durations to reduce inflammation and pruritus of the skin. Avoid long-term use on thin skin.

- Treat Edema: Diuretics may be considered in cases of significant generalized edema, but direct management of venous hypertension with compression is primary.

- Wound Care (for Ulceration): Management of venous ulcers includes debridement, appropriate dressings (e.g., hydrocolloids, foams), and continued compression. Referral to a wound care specialist.

- Infection Management: Prompt recognition and treatment of secondary bacterial infections (cellulitis) with systemic antibiotics.

- Vein Surgery/Intervention: Referral to a vascular specialist may be considered for underlying venous insufficiency (e.g., varicose vein ablation, venous valve repair) if conservative measures are insufficient.

- Avoidance of Irritants: Avoid applying sensitizing topical products (e.g., neomycin, lanolin) to already compromised skin, as this can lead to superimposed ACD.

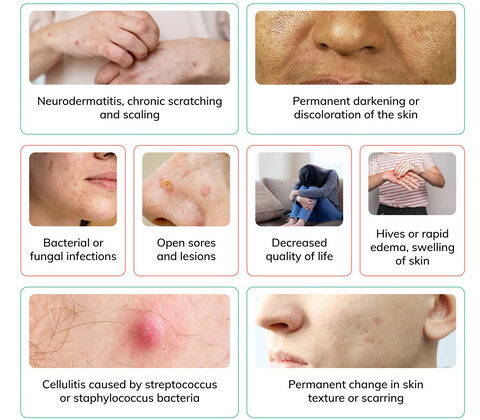

- Secondary Bacterial Infections:

- Mechanism: Disruption of the skin barrier (due to inflammation, scratching, fissures) creates entry points for bacteria, particularly Staphylococcus aureus, which commonly colonizes eczematous skin.

- Clinical Presentation: Impetiginization (yellow-brown crusts, honey-crusted lesions), pustules, folliculitis. Can progress to cellulitis, especially in stasis dermatitis (erythema, warmth, pain, swelling).

- Management: Topical antibiotics for localized infection (e.g., mupirocin), systemic antibiotics for widespread or severe infections. Dilute bleach baths can help reduce S. aureus colonization.

- Secondary Viral Infections:

- Mechanism: Compromised skin barrier makes individuals more susceptible to viral infections, particularly Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV).

- Eczema Herpeticum (EH) / Kaposi's Varicelliform Eruption: A severe, widespread HSV infection occurring on eczematous skin.

- Clinical Presentation: Monomorphic, painful, punched-out erosions or vesicles, often with fever and lymphadenopathy. Can be life-threatening if it spreads to organs.

- Management: Prompt systemic antiviral therapy (e.g., acyclovir, valacyclovir).

- Secondary Fungal Infections:

- Mechanism: Increased moisture (e.g., intertriginous areas in seborrheic dermatitis, occluded skin in stasis dermatitis) and compromised skin can predispose to fungal overgrowth.

- Clinical Presentation: Tinea (e.g., tinea corporis, tinea pedis) with annular lesions, or candidiasis (bright red, often with satellite lesions) in intertriginous areas.

- Management: Topical or systemic antifungals.

- Lichenification:

- Mechanism: Chronic scratching and rubbing lead to epidermal hyperplasia and dermal fibrosis.

- Clinical Presentation: Thickened, leathery skin with exaggerated skin markings. Often seen in chronic AD, CD, and areas of persistent pruritus.

- Management: Potent topical corticosteroids, emollients, and breaking the itch-scratch cycle.

- Post-Inflammatory Hyperpigmentation (PIH) or Hypopigmentation (PIH):

- Mechanism: Inflammation can affect melanocytes, leading to either increased melanin production (hyperpigmentation) or decreased melanin production (hypopigmentation).

- Clinical Presentation: Darkening (brown/black) or lightening (white) of the skin in areas where dermatitis has healed. More prominent in individuals with darker skin tones.

- Management: Often resolves spontaneously over time, but can be slow. Sun protection is key. Topical retinoids or hydroquinone for hyperpigmentation may be used cautiously.

- Excoriations:

- Mechanism: Skin damage resulting from scratching.

- Clinical Presentation: Linear abrasions, often crusted. Increases risk of secondary infection and scarring.

- Management: Anti-itch strategies, wound care, and behavioral interventions to reduce scratching.

- Scarring:

- Mechanism: Severe inflammation, deep excoriations, or secondary infections (e.g., cellulitis, extensive eczema herpeticum) can lead to permanent skin damage.

- Clinical Presentation: Depressed, raised, or discolored scars.

- Psychosocial Impact:

- Mechanism: Chronic, visible skin disease can significantly affect quality of life, sleep, self-esteem, and social interactions. Pruritus can lead to sleep disturbance, fatigue, and irritability.

- Clinical Presentation: Anxiety, depression, social isolation, poor sleep quality, impaired academic/work performance.

- Management: Psychosocial support, counseling, addressing sleep disturbances, and effective disease control.

- Growth Retardation: In severe, chronic AD, especially in children, due to inflammation, sleep disturbance, and sometimes systemic medications.

- Ocular Complications: Atopic keratoconjunctivitis, anterior subcapsular cataracts, retinal detachment (rare).

- Food Allergies/Asthma/Allergic Rhinitis: AD is often the "first march" in the atopic march, predisposing individuals to other atopic diseases.

- Erythroderma: Rare but severe complication where nearly the entire skin surface becomes red and inflamed, leading to systemic effects like temperature dysregulation and fluid loss.

- Chronic Eczema: If the irritant/allergen is not identified and removed, the acute contact dermatitis can become chronic, leading to lichenification and persistent symptoms.

- Occupational Disability: For work-related contact dermatitis, failure to manage can lead to prolonged absence from work or inability to perform certain tasks, leading to changes in occupation.

- Blepharitis: Inflammation of the eyelid margins, often seen with scalp or facial SD.

- Widespread or Exfoliative Dermatitis: In severe, generalized cases, particularly in immunocompromised individuals (e.g., HIV/AIDS), SD can become extensive and difficult to control.

- Venous Ulcers: The most significant and common complication. Chronic venous hypertension and inflammation lead to skin breakdown, resulting in poorly healing wounds, typically around the ankles.

- Lipodermatosclerosis: Chronic inflammation and fibrosis of subcutaneous tissue, leading to a "champagne bottle" or "inverted wine bottle" appearance of the lower leg, with hardening and induration of the skin.

- Atrophie Blanche: Scarred, porcelain-white areas of skin, often painful, surrounded by telangiectasias and hyperpigmentation, typically seen in the context of healed or chronic venous ulcers.

- Recurrent Cellulitis: Stasis dermatitis impairs local immunity and skin barrier function, increasing susceptibility to recurrent bacterial infections.

- Chronic Edema: Persistent swelling due to impaired venous and lymphatic drainage, further exacerbating skin changes.

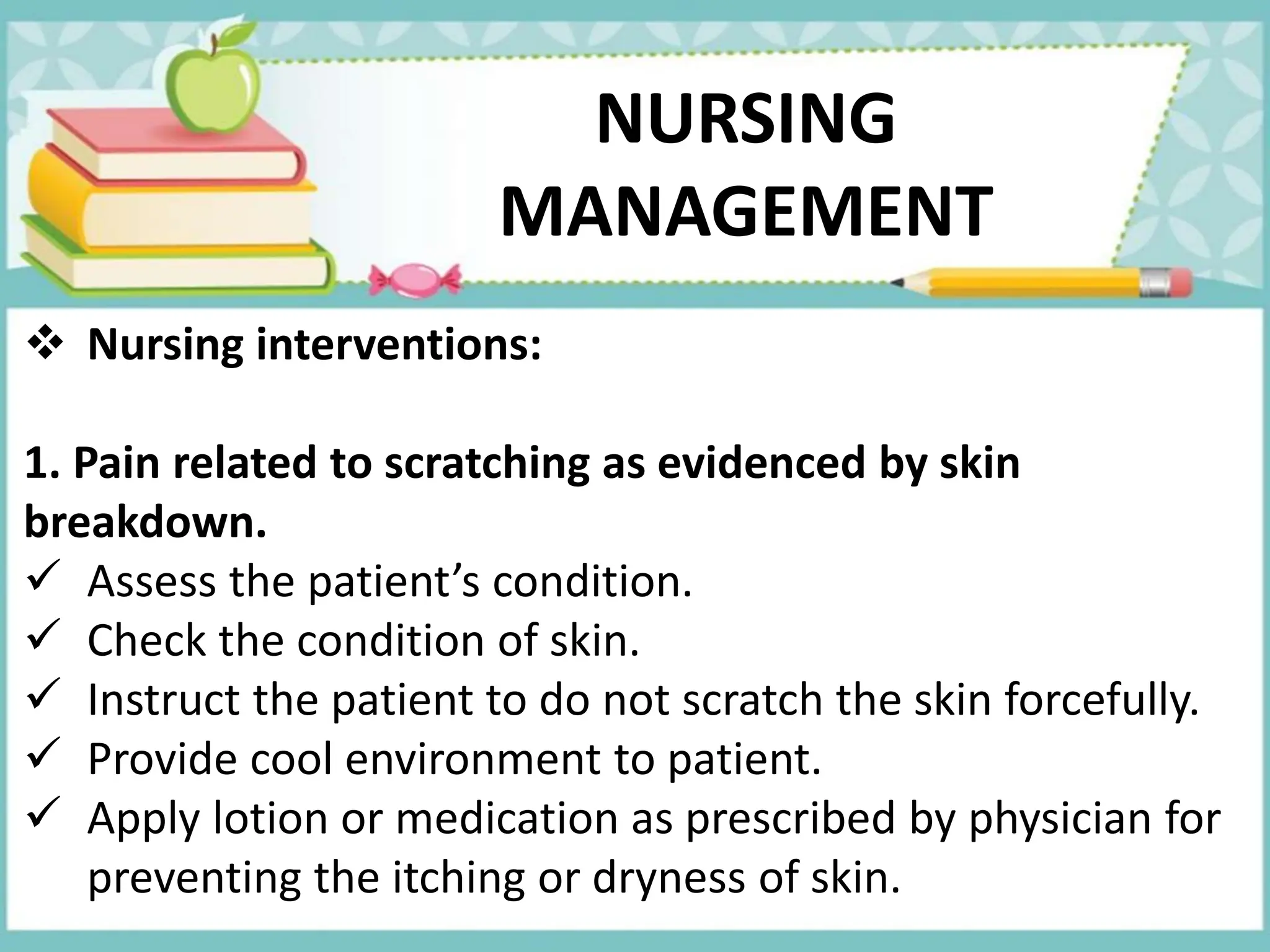

- Impaired Skin Integrity related to inflammatory process, dry skin, excoriation, and altered skin barrier function.

- Defining Characteristics: Disruption of skin surface, erythema, edema, scaling, crusting, lichenification, presence of lesions (papules, vesicles), excoriations, secondary infection.

- Chronic Pain or Acute Pain related to skin inflammation, pruritus, and scratching.

- Defining Characteristics: Verbal reports of itching or burning, restless sleep, irritability, scratching behaviors, guarding inflamed areas, altered activity level. (For pruritus, "Impaired Comfort: Pruritus" is also a very appropriate diagnosis.)

- Disrupted Body Image related to visible skin lesions, scarring, and chronic nature of the condition.

- Defining Characteristics: Negative feelings about body, feelings of shame or embarrassment, social isolation, reluctance to expose affected skin, altered social participation.

- Inadequate health Knowledge related to disease process, triggers, treatment regimen, and prevention of complications.

- Defining Characteristics: Verbalized misconceptions, inadequate adherence to treatment, inappropriate skin care practices, questions about condition, recurrence of flares.

- Risk for Infection related to impaired skin barrier, excoriations, and presence of open lesions.

- Defining Characteristics: (This is a risk diagnosis, so no defining characteristics, but risk factors include) broken skin, compromised immune status (especially for severe AD or SD), colonization with pathogenic organisms (e.g., S. aureus).

- Sleep Deprivation related to intense pruritus, discomfort, and scratching at night.

- Defining Characteristics: Verbal reports of difficulty falling asleep or staying asleep, fatigue, irritability, reduced concentration, dark circles under eyes.

- Ineffective Health Maintenance related to insufficient knowledge about therapeutic regimen, lack of resources, or perceived lack of control over chronic illness.

- Defining Characteristics: Recurrent exacerbations, non-adherence to medication/treatment, inadequate self-care practices.

- Social Isolation related to embarrassment about skin condition or fear of negative judgment from others.

- Defining Characteristics: Expresses feelings of loneliness, withdrawal, lack of social contact, reluctance to participate in social activities.

- Regularly assess skin for color, temperature, turgor, integrity, presence of lesions, erythema, scaling, edema, crusting, excoriations. Document size, location, and characteristics of lesions.

- Monitor for signs of infection (e.g., increased warmth, pain, purulent drainage, fever).

- Cleanse skin gently with mild, non-perfumed cleansers and lukewarm water. Pat dry, do not rub.

- Apply prescribed topical medications (corticosteroids, TCIs, emollients) as directed, ensuring correct technique and amount. Educate patient on proper application.

- Apply emollients liberally and frequently (at least BID), especially after bathing, to "trap" moisture.

- Implement wet wraps or damp dressings as prescribed to soothe, reduce inflammation, and enhance medication absorption.

- Advise patient to wear loose-fitting, soft cotton clothing to minimize irritation.

- Recommend protective gloves for hands if irritation or contact dermatitis is present (e.g., for household chores).

- Keep fingernails short and smooth to minimize skin damage from scratching.

- Administer prescribed oral antihistamines (especially sedating ones at night) to reduce itching and promote sleep. Educate on side effects (drowsiness).

- Administer prescribed topical antipruritics (e.g., pramoxine) as needed.

- Encourage cool compresses or cool baths (oatmeal baths can be soothing).

- Advise against hot showers/baths, which can exacerbate itching.

- Teach relaxation techniques (deep breathing, meditation) to manage the urge to scratch.

- Distraction techniques, especially for children.

- Ensure a cool, humidified environment to prevent skin dryness.

- Provide a non-judgmental and empathetic environment.

- Educate patient and family about the chronic nature of the condition and that it is not contagious.

- Encourage expression of feelings about their skin condition and its impact on their life.

- Highlight the positive aspects of treatment adherence and improvements.

- Suggest support groups or counseling to help cope with the emotional and social challenges.

- Encourage participation in activities they enjoy, adapting as needed.

- Provide resources for psychosocial support.

- Assess current knowledge level and readiness to learn.

- Provide clear, consistent, and individualized education on:

- Disease process: What dermatitis is, its causes, and its chronic nature.

- Triggers: Help identify and avoid personal triggers (e.g., irritants, allergens, stress, harsh chemicals, specific foods if clearly linked).

- Medication regimen: Name, purpose, dose, route, frequency, duration, side effects, and proper application technique for all prescribed medications (topical and systemic).

- Skin care routine: Emphasize daily moisturization, gentle bathing, and avoiding harsh soaps.

- Signs of complications: What to look for (e.g., signs of infection) and when to seek medical attention.

- Importance of adherence: Explain that consistent management prevents flares and complications.

- Use teach-back method to confirm understanding.

- Provide written materials, reputable websites, or patient education pamphlets.

- Involve family members or caregivers in the education process.

- Strict hand hygiene before and after touching affected skin.

- Educate on avoiding scratching; use anti-itch strategies.

- Monitor for signs of secondary infection (redness, warmth, swelling, pain, pus, fever, lymphadenopathy).

- Administer prescribed antibiotics/antivirals/antifungals promptly if infection is present.

- Encourage a cool, dark, quiet bedroom environment.

- Advise establishing a consistent bedtime routine.

- Ensure effective itch control (antihistamines, topical treatments) before bed.

- Suggest cool compresses before sleep if itching is severe.

- Explain the link between itching and sleep disturbance.

- Advise against caffeine or heavy meals before bedtime.

- Reduced inflammation and pruritus.

- Intact skin without excoriations or signs of infection.

- Improved sleep patterns.

- Verbalization of increased comfort.

- Expression of positive feelings about body image.

- Demonstration of correct medication application and adherence to skin care regimen.

- Identification and avoidance of triggers.

- Absence of complications.

- Consistent Skin Barrier Maintenance:

- Daily Emollients: Emphasize the daily, liberal, and consistent use of thick moisturizers (creams or ointments, not lotions) even when the skin appears clear. This is the cornerstone of preventing flares in conditions like AD.

- Gentle Cleansing: Continue to use mild, fragrance-free cleansers and lukewarm water for baths/showers. Avoid harsh scrubbing.

- Humidity Control: Maintain adequate humidity in living spaces, especially during dry seasons, using humidifiers.

- Proactive Anti-inflammatory Therapy (for AD):

- Maintenance Therapy: For individuals with frequently flaring AD, a proactive approach using topical corticosteroids or topical calcineurin inhibitors 2-3 times a week on previously affected areas (even when asymptomatic) can prevent relapses. This differs from reactive treatment of acute flares.

- Trigger Identification and Avoidance:

- Personalized Approach: Work with patients to identify their specific triggers (e.g., environmental allergens, irritants, stress, certain fabrics, prolonged sweating, specific foods if proven).

- Avoidance Strategies: Provide practical advice on how to avoid these triggers (e.g., dust mite covers, wearing gloves, stress management techniques, avoiding known contact allergens).

- Regular Follow-up and Monitoring:

- Scheduled Appointments: Encourage regular check-ups with healthcare providers (dermatologist, primary care) to monitor disease activity, assess treatment effectiveness, and adjust therapy as needed.

- Self-Monitoring: Teach patients to monitor their skin condition and recognize early signs of a flare-up so they can intervene promptly.

- Adherence to Treatment Regimens:

- Simplified Regimens: Whenever possible, simplify treatment plans to improve adherence.

- Reinforcement: Continuously reinforce the importance of consistent medication use, even when symptoms improve, to maintain remission.

- Addressing Psychosocial Factors:

- Stress Management: Provide resources and strategies for stress reduction (e.g., mindfulness, relaxation techniques, counseling), as stress can be a significant trigger for flares.

- Support Networks: Encourage participation in support groups or connecting with others who have similar conditions.

- Mental Health: Screen for and address anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbances, which can exacerbate dermatitis.

- Management of Comorbidities:

- Atopic March: For AD patients, manage associated atopic conditions (asthma, allergic rhinitis, food allergies).

- Venous Insufficiency: For stasis dermatitis, aggressive long-term management of underlying chronic venous insufficiency is paramount (e.g., consistent compression therapy, regular leg elevation, exercise).

- Understanding the Disease:

- Name and Type: Clearly explain the specific type of dermatitis they have and its characteristics.

- Chronic Nature: Emphasize that many forms are chronic and require ongoing management, even during periods of remission. It is not "curable" but "controllable."

- Non-Contagious: Reassure them that dermatitis is not contagious.

- Trigger Identification and Avoidance:

- Personal Triggers: Help them identify and keep a log of potential triggers.

- Environmental: Discuss common irritants (soaps, detergents, solvents), allergens (nickel, fragrances, plants), environmental factors (dust mites, pet dander, pollen, dry air), and extreme temperatures.

- Lifestyle: Discuss stress, sweating, tight clothing.

- Dietary: If specific food allergies are proven triggers, advise on strict avoidance.

- Proper Skin Care Practices:

- Bathing: Short, lukewarm baths/showers (5-10 minutes). Use mild, fragrance-free cleansers. Avoid scrubbing. Pat skin dry gently.

- Moisturization: Apply emollients liberally within 3 minutes of bathing/showering to damp skin. Reapply throughout the day. Advise on choosing appropriate moisturizers (ointments/creams vs. lotions).

- Clothing: Recommend soft, breathable fabrics (e.g., cotton). Avoid wool or synthetic materials that can irritate.

- Nail Care: Keep fingernails short and smooth to minimize skin damage from scratching.

- Medication Adherence and Proper Application:

- Purpose and Expectations: Explain the purpose of each medication (e.g., steroids reduce inflammation, emollients moisturize) and what to expect.

- Application Technique: Demonstrate correct application (e.g., thin layer, rub in gently, on affected areas only for active treatment).

- Side Effects: Discuss potential side effects and when to report them.

- "Fear of Steroids": Address corticosteroid phobia by explaining appropriate use, potency, and duration to minimize side effects.

- Maintenance vs. Acute Treatment: Differentiate between daily preventative care and treatment for flares.

- Pruritus Management:

- Itch-Scratch Cycle: Explain how scratching perpetuates the itch and damages the skin.

- Strategies: Discuss non-pharmacological (cool compresses, distraction, relaxation) and pharmacological (antihistamines) strategies.

- Recognition and Management of Flares and Complications:

- Early Signs of Flare: Teach patients to recognize early signs of worsening dermatitis.

- Signs of Infection: Educate on symptoms of bacterial (pus, spreading redness, fever), viral (painful clusters of blisters), and fungal infections.

- When to Seek Medical Attention: Provide clear guidelines on when to contact a healthcare provider (e.g., signs of infection, severe itching, spreading rash, fever, worsening symptoms despite treatment).

- Psychosocial Support:

- Coping Strategies: Discuss ways to cope with the emotional impact of chronic skin conditions.

- Communication: Encourage open communication with family, friends, and healthcare providers.

- Resources: Provide information on support groups or counseling services.

Management focuses on improving venous return, reducing edema, and treating skin inflammation and complications.

Dermatitis, particularly chronic forms, can lead to various complications, ranging from secondary infections to long-term skin changes and impacts on quality of life.

For patients with dermatitis, these diagnoses often revolve around skin integrity, comfort, knowledge deficits, and psychosocial well-being.

Interventions should be tailored to the specific nursing diagnoses and individual patient needs, emphasizing a holistic approach.

| Action/Assessment | Detail/Rationale |

|---|---|

| Assessment |

|

| Wound Care/Topical Applications |

|

| Protection |

|

| Action/Assessment | Detail/Rationale |

|---|---|

| Pharmacological |

|

| Non-Pharmacological |

|

| Action/Assessment | Detail/Rationale |

|---|---|

| Support and Education |

|

| Coping Strategies |

|

| Action/Assessment | Detail/Rationale |

|---|---|

| Education |

|

| Reinforcement |

|

| Action/Assessment | Detail/Rationale |

|---|---|

| Prevention |

|

| Action/Assessment | Detail/Rationale |

|---|---|

| Environment and Routine |

|

| Symptom Management |

|

| Education |

|

Nurses continuously evaluate the effectiveness of interventions by monitoring patient outcomes, including:

Dermatitis, particularly chronic forms like Atopic Dermatitis, Seborrheic Dermatitis, and Stasis Dermatitis, requires ongoing management and a proactive approach to prevent flares and maintain remission.

Effective patient education is a continuous partnership between the healthcare team and the patient/family.

so interesting