Table of Contents

ToggleGASTRITIS

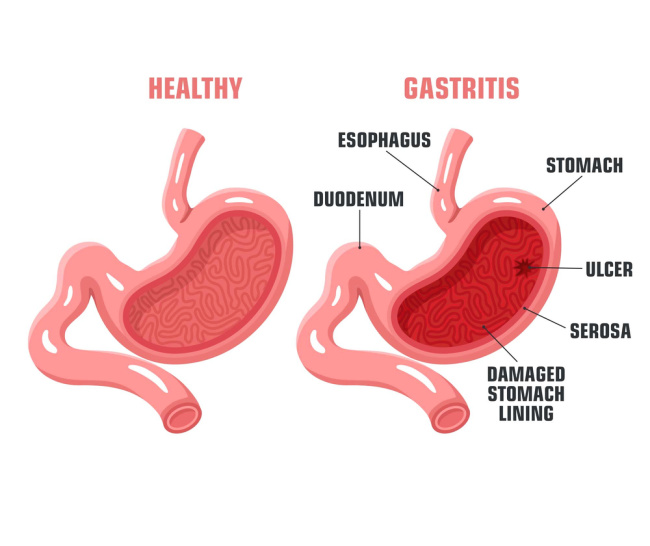

Gastritis is fundamentally an inflammation of the gastric mucosa, which is the delicate inner lining of the stomach. This inflammatory response can be widespread (diffuse) or confined to specific areas (localized) within the stomach, and it represents the body's reaction to various forms of injury or infection. Gastritis is broadly categorized into two main types based on its duration and onset: acute and chronic.

Acute Gastritis: Sudden Onset and Short-Term Inflammation

Acute gastritis is characterized by a rapid onset of inflammatory changes in the stomach lining, typically lasting for a relatively short duration—from several hours to a few days. It is frequently triggered by direct exposure to various local irritants or systemic factors.

Causes of Acute Gastritis

- Dietary Indiscretion: Ingestion of foods that are irritating, excessively seasoned, very hot or cold, or contaminated with bacteria or toxins (e.g., in cases of food poisoning).

- Medications: The most common culprits include the excessive or prolonged use of aspirin and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like ibuprofen and naproxen. These drugs can disrupt the stomach's protective mucosal barrier.

- Irritants: Significant and excessive intake of alcohol is a potent irritant that can directly damage the gastric lining.

- Bile Reflux: The abnormal regurgitation of bile from the duodenum (the first part of the small intestine) back into the stomach can cause chemical irritation of the gastric mucosa.

- Radiation Therapy: Therapeutic radiation directed at the abdominal area, particularly for certain cancers, can lead to direct damage and inflammation of the gastric mucosa.

- Severe Physiological Stress: Extreme physical stress, such as that experienced during major surgical procedures, extensive burns, severe trauma, sepsis, multiple organ failure, or significant central nervous system (CNS) injury (e.g., head trauma), can induce stress-related erosive gastritis or stress ulcers. This is often due to reduced blood flow to the gastric lining.

- Chemicals: Accidental or intentional ingestion of strong corrosive agents like acids or alkalis can lead to severe mucosal injury, potentially causing the lining to become gangrenous (tissue death) or even perforate (form a hole).

- Systemic Infections: In some cases, acute gastritis can be an early or accompanying symptom of a broader systemic infection, such as viral infections (e.g., norovirus, rotavirus) or bacterial infections elsewhere in the body.

- Acute Viral or Bacterial Infections of the Stomach: Infections directly affecting the stomach lining, often leading to gastroenteritis (inflammation of both stomach and intestines).

Clinical Manifestations of Acute Gastritis

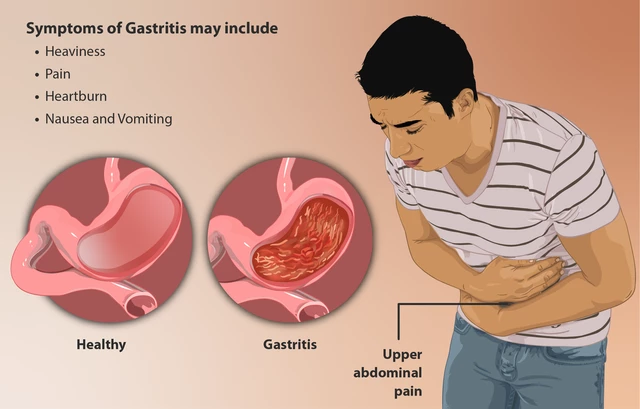

The symptoms of acute gastritis usually appear suddenly and can range in severity:

- Onset of symptoms is often rapid and can be quite distressing.

- Abdominal Discomfort or Cramping: A general feeling of unease or colicky pain in the upper abdomen.

- Epigastric Pain or Tenderness: Localized pain or sensitivity in the upper central part of the abdomen, just below the breastbone.

- Headache and Lassitude: Generalized fatigue, weakness, and headache can accompany the gastric symptoms, especially in more severe cases or with systemic causes.

- Nausea and Vomiting: Common symptoms, with vomiting often providing temporary relief. The vomitus may contain food, bile, or even streaks of blood.

- Anorexia: A significant loss of appetite due to discomfort and nausea.

- Hiccupping: Persistent hiccups can occur due to irritation of the diaphragm.

- Diarrhea: May be present, especially if the cause is food poisoning or a systemic infection affecting the intestines as well.

- Painless GI Bleeding: This is a serious potential complication, particularly in individuals who have consumed large amounts of alcohol or are regular users of aspirin and NSAIDs. Bleeding can manifest as hematemesis (vomiting blood, which may look like "coffee grounds") or melena (black, tarry stools due to digested blood).

Chronic Gastritis

Chronic gastritis is characterized by prolonged inflammation of the stomach lining, often leading to structural changes in the mucosa over time, such as glandular atrophy (wasting away of the glands) or metaplasia (change in cell type). Unlike acute gastritis, its onset can be insidious, and symptoms may be less severe but persistent or intermittent. It may be caused by benign or malignant ulcers, but the most prevalent cause is a specific bacterial infection.

Causes of Chronic Gastritis

- Bacterial Infection: The single most common cause worldwide is chronic infection with the bacterium Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori). This bacterium colonizes the stomach lining and causes ongoing inflammation, which can progress to atrophy and increase the risk of peptic ulcers and gastric cancer.

- Autoimmune Diseases: In some cases, the body's immune system mistakenly attacks its own stomach cells. A notable example is autoimmune gastritis, which is strongly associated with pernicious anemia, where the immune system destroys parietal cells responsible for producing intrinsic factor (necessary for Vitamin B12 absorption).

- Dietary Factors: Chronic and excessive intake of certain irritants, such as large amounts of caffeine or highly processed foods, can contribute to chronic inflammation over time.

- Chronic Medication Use: Long-term, regular use of NSAIDs is a significant contributor to chronic gastritis, similar to acute forms, but with persistent damage.

- Lifestyle Factors: Chronic and excessive alcohol consumption and smoking are well-established risk factors that cause persistent irritation and impair the stomach's protective mechanisms.

- Chronic Reflux: Persistent and significant reflux of bile and pancreatic secretions from the duodenum into the stomach can lead to ongoing chemical irritation and chronic inflammation. This is often seen after certain types of gastric surgery (e.g., gastrectomy).

- Recurring Episodes of Untreated Acute Gastritis: If acute gastritis episodes are frequent, severe, or inadequately managed, the persistent irritation can eventually lead to chronic changes in the gastric mucosa.

- Granulomatous Conditions: Rarer causes include inflammatory conditions like Crohn's disease or sarcoidosis that can affect the stomach.

Clinical Manifestations of Chronic Gastritis

The symptoms of chronic gastritis can be less dramatic than acute forms and may even be subtle or absent for extended periods:

- May be Asymptomatic: Many individuals with chronic gastritis, especially those with H. pylori infection, may experience no symptoms for years, or only vague digestive discomfort.

- Anorexia: A persistent or intermittent loss of appetite.

- Heartburn: A burning sensation in the chest, particularly after eating, similar to indigestion.

- Belching or a Sour Taste in the Mouth: Frequent burping and a persistent unpleasant, sour, or metallic taste can be present due to impaired digestion or reflux.

- Nausea and Vomiting: These symptoms can occur intermittently, usually less severe than in acute gastritis.

- Malabsorption of Vitamin B12: This is a crucial manifestation of autoimmune gastritis or advanced H. pylori-induced atrophic gastritis. Chronic inflammation, particularly when leading to atrophy of parietal cells, can significantly reduce the production of intrinsic factor. Intrinsic factor is essential for the absorption of dietary vitamin B12 in the small intestine. This malabsorption can lead to pernicious anemia (a type of megaloblastic anemia) and neurological complications if left untreated.

- Feeling of Fullness: A sensation of feeling full very quickly after starting a meal (early satiety).

- Epigastric Discomfort: Vague, dull ache or discomfort in the upper abdomen, often worse after meals.

Investigations for Gastritis

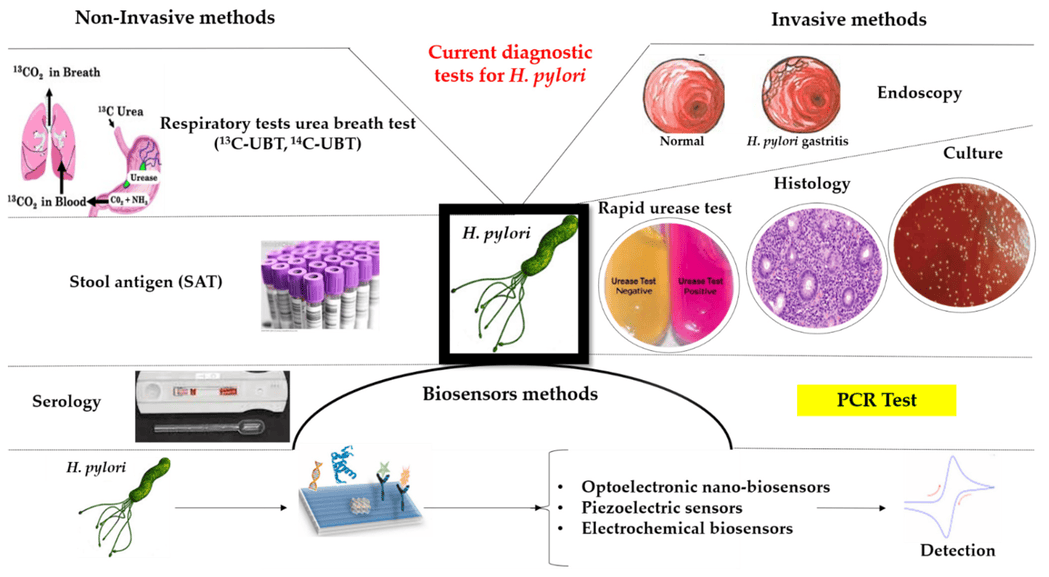

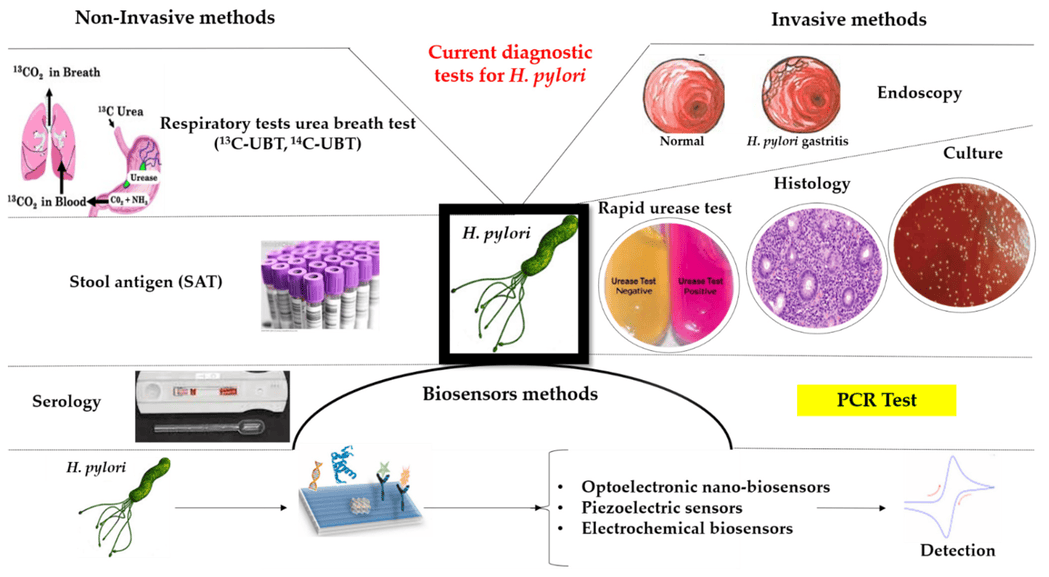

Accurate diagnosis of gastritis, and more importantly, its underlying cause, is crucial for effective treatment and preventing complications. A combination of clinical assessment and specific diagnostic tests is usually employed.

- Visualization: A thin, flexible tube with a camera is inserted through the mouth to directly visualize the gastric mucosa, allowing the clinician to observe the extent and characteristics of the inflammation (e.g., redness, erosions, atrophy).

- Biopsy: During endoscopy, small tissue samples (biopsies) can be taken from the stomach lining. These samples are then sent for histopathological examination.

- Confirmation of Gastritis: The biopsy confirms the presence of inflammation and helps to differentiate between acute and chronic forms.

- Rule out Malignancy: It is essential for ruling out dysplastic changes or gastric malignancy, especially in cases of chronic gastritis or suspicious lesions.

- Identify Histological Changes: It can identify specific features like glandular atrophy, intestinal metaplasia, and the presence of H. pylori.

- Urea Breath Test: A non-invasive test where the patient ingests a urea-containing tablet. If H. pylori is present, it breaks down the urea, releasing carbon dioxide that can be detected in the breath.

- Stool Antigen Test: A non-invasive test that detects H. pylori antigens in a stool sample.

- Blood Test (Serology): Detects antibodies to H. pylori. While indicating past exposure, it cannot differentiate between active infection and successfully treated infection.

- Biopsy-based Tests: Rapid Urease Test (RUT) on a biopsy sample obtained during endoscopy, or histological examination of the biopsy itself.

- Visualization: After ingesting a barium-containing liquid, X-ray images are taken to outline the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum.

- Evaluation for Complications: While less sensitive for diagnosing gastritis itself than endoscopy, it can help identify complications such as structural abnormalities (e.g., strictures), severe ulcerations, or signs of perforations. It is generally used when endoscopy is not available or contraindicated.

- Occult Blood Test: To check for hidden (occult) blood in the stool. A positive result indicates gastrointestinal bleeding, which can occur in both acute and chronic gastritis, especially erosive forms or if ulcers are present.

- Complete Blood Count (CBC): To check for anemia (especially iron deficiency anemia due to chronic blood loss or pernicious anemia due to B12 malabsorption).

- Vitamin B12 Levels: Crucial in suspected autoimmune gastritis to assess for pernicious anemia.

- Electrolyte Levels: Especially if there is significant vomiting.

Management of Gastritis

The effective management of gastritis is multifaceted, encompassing both non-pharmacological and pharmacological strategies. The primary goals are to identify and eliminate the causative agents, alleviate symptoms, promote healing of the gastric mucosa, and prevent recurrence and complications. A patient-centered approach, including education and support, is crucial for successful outcomes.

Non-Pharmacological Management: Lifestyle and Dietary Modifications

These interventions are foundational to gastritis management and often provide significant relief, particularly in mild to moderate cases.

Dietary Changes: Tailoring the diet to minimize irritation and promote healing. Avoidance of Irritants: Strictly avoid foods and beverages known to irritate the stomach lining. This commonly includes:- Spicy foods (e.g., chilies, hot sauces)

- Acidic foods and beverages (e.g., citrus fruits and juices, tomatoes, vinegar)

- Carbonated drinks

- Caffeine (coffee, tea, energy drinks)

- Alcohol (a direct gastric irritant)

- Fatty and fried foods (can delay gastric emptying and increase acid production)

- Certain dairy products (for some individuals)

- Smaller, More Frequent Meals: Instead of three large meals, encourage 5-6 smaller meals throughout the day. This helps to maintain a consistent stomach environment and avoids overfilling the stomach, which can stimulate excessive acid secretion.

- Regular Meal Times: Eating at consistent times helps regulate digestive processes and acid production.

- Eat Slowly and Chew Thoroughly: Aids digestion and reduces the amount of air swallowed.

- Avoid Eating Before Bed: Do not eat for at least 2-3 hours before lying down to prevent reflux and nocturnal acid secretion.

- Lean proteins (baked chicken, fish)

- Non-acidic fruits (apples, bananas, pears)

- Cooked vegetables (steamed, boiled)

- Whole grains (oatmeal, brown rice)

- Low-fat dairy (if tolerated)

- Avoidance of Smoking and Alcohol Intake: Both are direct irritants to the gastric mucosa and impair healing. Smoking also reduces blood flow to the stomach lining.

- Avoidance of Chronic Use of NSAIDs: Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (e.g., ibuprofen, naproxen, aspirin) are a very common cause of gastritis and peptic ulcers. If pain relief is needed, acetaminophen (Paracetamol) is generally preferred. If NSAIDs are unavoidable, they should be taken with food and possibly with a gastroprotective agent (like a PPI).

- Stress Reduction and Management Techniques: Psychological stress can exacerbate gastritis symptoms by influencing gastric acid secretion and motility. Techniques include:

- Mindfulness and meditation

- Deep breathing exercises

- Yoga or Tai Chi

- Regular physical activity (non-strenuous)

- Adequate sleep

- Seeking support from counseling or therapy if stress is severe.

- Weight Management: If overweight or obese, losing weight can help reduce pressure on the abdomen and lessen reflux symptoms, which can sometimes contribute to gastritis.

Pharmacological Treatment: Targeting Acid and Infection

Medications are often necessary to reduce stomach acid, protect the gastric lining, and eradicate infections.

Antacids: Provide immediate, temporary relief by neutralizing existing stomach acid.- Mechanism: Act as weak bases that directly react with hydrochloric acid in the stomach.

- Examples: Magnesium Trisilicate (tablets or suspensions), Aluminum Hydroxide/Magnesium Hydroxide combinations (e.g., Relcer gel, Ulgel, Maalox).

- Dosage: Typically 10-20mL or 1-2 tablets taken 30 minutes to 1 hour after meals and at bedtime.

- Considerations: Magnesium-containing antacids can cause diarrhea; aluminum-containing antacids can cause constipation. Combinations help balance these effects.

- Mechanism: Block H2 receptors on gastric parietal cells, leading to decreased histamine-stimulated acid secretion.

- Examples: Ranitidine (150mg), Famotidine (20mg, 40mg), Cimetidine (less commonly used due to drug interactions).

- Dosage: Usually taken once or twice daily, depending on the severity of symptoms.

- Considerations: Generally well-tolerated; available over-the-counter and by prescription. Provide longer-lasting acid control than antacids.

- Mechanism: Irreversibly block the H+/K+-ATPase pump (proton pump) in gastric parietal cells, effectively shutting down acid production.

- Examples: Omeprazole (20mg, 40mg), Rabeprazole (20mg), Lansoprazole (15mg, 30mg), Pantoprazole (20mg, 40mg), Esomeprazole (20mg, 40mg).

- Dosage: Typically taken once daily, 30-60 minutes before the first meal of the day for maximal effect.

- Considerations: Highly effective for healing and preventing recurrence. Long-term use requires monitoring due to potential side effects (e.g., increased risk of C. difficile infection, bone fractures, nutrient malabsorption).

Supportive Therapy

Analgesics: For pain relief, especially during acute flares.- Paracetamol (Acetaminophen): Generally preferred over NSAIDs for pain management in gastritis patients due to its lower risk of gastric irritation. Dosage typically 500mg or 1g orally three times daily for 3-5 days, or as prescribed, ensuring daily maximum dose is not exceeded.

- Avoid NSAIDs: Unless absolutely necessary and with gastroprotective co-medication.

- Mechanism: Improve gastric motility and emptying.

- Examples: Metoclopramide, Domperidone.

- Considerations: Potential for side effects (e.g., neurological for metoclopramide).

- Sucralfate: Forms a protective barrier over the ulcerated or inflamed mucosa, shielding it from acid and enzymes. Does not alter acid secretion.

- Bismuth Subsalicylate: Has some mucosal protective properties and also antibacterial effects against H. pylori.

NOTE: If the cause of gastritis is confirmed to be Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) bacteria, eradication therapy is essential to prevent recurrence and complications like peptic ulcers and gastric cancer. Treatment typically involves a combination therapy, known as "triple therapy" or "quadruple therapy":

Triple Therapy: Usually comprises one PPI and two antibiotics for 10-14 days.- Common Regimen: PPI (e.g., Omeprazole 20mg twice daily) + Clarithromycin (500mg twice daily) + Amoxicillin (1000mg twice daily).

- Alternative (if penicillin allergy): PPI + Clarithromycin + Metronidazole (400-500mg twice daily).

- Common Regimen: PPI + Bismuth + Metronidazole + Tetracycline.

- Strict adherence to the medication regimen is crucial for successful eradication and to prevent antibiotic resistance.

- Side effects (nausea, diarrhea, metallic taste) are common with antibiotic combinations.

- Follow-up testing (urea breath test, stool antigen test) is recommended 4-6 weeks after completing therapy to confirm eradication.

Nursing Diagnoses and Interventions for Gastritis

Nursing care for patients with gastritis focuses on symptom management, patient education, emotional support, and monitoring for complications. Here are common nursing diagnoses and associated interventions:

1. Acute Pain

Definition: Unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage; sudden or slow onset of any intensity from mild to severe with an anticipated or predictable end.Related to: Irritated gastric mucosa, increased gastric acid secretion, inflammation.

Assessment:

- Monitor pain characteristics (location, intensity, quality, duration) using a pain scale (e.g., 0-10).

- Observe non-verbal cues of pain (restlessness, grimacing, guarding).

- Assess factors that aggravate or relieve pain.

Interventions:

- Administer prescribed analgesics (e.g., Paracetamol) as ordered, and evaluate effectiveness.

- Administer antacids, H2RAs, or PPIs as prescribed; educate on proper timing (e.g., PPIs before meals, antacids after meals).

- Teach and encourage non-pharmacological pain relief methods:

- Applying warm compresses to the abdomen.

- Relaxation techniques (deep breathing, guided imagery).

- Distraction.

- Encourage small, frequent, bland meals.

- Avoid known gastric irritants (spicy food, caffeine, alcohol, NSAIDs).

- Provide a quiet and comfortable environment.

2. Inadequate protein energy intake

Definition: Intake of nutrients insufficient to meet metabolic needs.Related to: Anorexia, nausea, vomiting, pain experienced with eating, dietary restrictions.

Assessment:

- Monitor weight, noting any losses.

- Assess dietary intake and eating patterns.

- Observe for signs of nutrient deficiencies.

- Note presence of nausea, vomiting, or early satiety.

Interventions:

- Encourage consumption of small, frequent meals of bland, easily digestible foods.

- Educate patient on foods to avoid (irritants) and foods to favor.

- Administer antiemetics as prescribed if nausea/vomiting is significant.

- Provide oral hygiene before and after meals to enhance appetite.

- Monitor fluid and electrolyte balance, especially if vomiting.

- Consider nutritional supplements if oral intake remains poor.

- Collaborate with a dietitian for comprehensive nutritional planning.

3. Deficient Knowledge

- Assess patient's current understanding of gastritis, its causes, management, and prevention.

- Identify learning style and readiness to learn.

- Evaluate patient's ability to adhere to treatment regimen.

- Provide clear, concise, and accurate information about gastritis, including:

- Nature of the disease and its common causes (e.g., H. pylori, NSAIDs, stress).

- Purpose, dosage, side effects, and proper timing of all prescribed medications (antacids, H2RAs, PPIs, antibiotics).

- Importance of adhering to the full course of H. pylori eradication therapy if applicable.

- Detailed dietary modifications (foods to avoid, foods to include, meal timing).

- Importance of lifestyle changes (smoking cessation, alcohol avoidance, stress management).

- Signs and symptoms of complications requiring immediate medical attention (e.g., severe abdominal pain, persistent vomiting, black tarry stools, coffee-ground emesis).

- Use various teaching methods (verbal instruction, written materials, visual aids).

- Encourage questions and allow time for discussion.

- Involve family members or caregivers in the education process as appropriate.

- Provide resources for further information and support.

4. Risk for Fluid Volume Deficit

- Monitor intake and output.

- Assess skin turgor, mucous membranes, and urine specific gravity.

- Monitor vital signs (tachycardia, hypotension, weak pulse).

- Observe for signs of dehydration (thirst, dizziness, decreased urine output).

- Monitor laboratory values (electrolytes, BUN, creatinine, hemoglobin, hematocrit).

- Encourage frequent sips of clear fluids (water, clear broths, diluted juices) if tolerated.

- Administer intravenous fluids as prescribed if oral intake is insufficient or if dehydration is present.

- Administer antiemetics to control nausea and vomiting.

- Monitor for signs of GI bleeding (hematemesis, melena) and report immediately.

- Educate patient on importance of hydration.

5. Nausea

- Assess the intensity and frequency of nausea.

- Note any precipitating or alleviating factors.

- Observe for associated symptoms like vomiting, excessive salivation, pallor, or sweating.

- Administer antiemetics as prescribed.

- Offer small, frequent, bland meals.

- Avoid strong odors (food, perfumes) that might trigger nausea.

- Encourage patient to rest in a comfortable position.

- Provide good oral hygiene.

- Suggest sipping on clear, cold liquids (e.g., ginger ale, clear broth).

- Educate on dietary modifications to reduce nausea.