Lymphangitis is an acute inflammation of the lymphatic vessels, typically caused by a bacterial infection spreading into the lymphatic system from an infected site. It is characterized by the appearance of red streaks or lines, often tender and warm, extending proximally from the site of infection towards regional lymph nodes.

- Acute Inflammation: It is a sudden onset inflammatory process.

- Lymphatic Vessels: The primary site of inflammation is within the lymphatic channels themselves.

- Infectious Etiology: Almost always caused by an infection, usually bacterial (most commonly Streptococcus pyogenes or Staphylococcus aureus).

- Spread Pattern: The classic presentation is visible red streaks following the superficial lymphatic pathways, moving away from the infection source towards the trunk.

- Systemic Symptoms: Often accompanied by systemic signs of infection such as fever, chills, malaise, and headache.

- Lymphadenitis: Frequently associated with regional lymphadenitis (inflammation and enlargement of the lymph nodes draining the affected area).

While lymphangitis and cellulitis often occur together, or one can precede the other, they are distinct conditions:

- Definition: An acute, spreading bacterial infection of the dermis and subcutaneous tissue.

- Appearance: Characterized by a localized area of redness (erythema), warmth, swelling, and tenderness that is typically diffuse, poorly demarcated, and spreads superficially. It does not usually present with distinct linear streaks.

- Location: Affects the skin and the tissue directly beneath it.

- Lymphatic Involvement: While cellulitis can lead to secondary lymphatic damage and can cause lymphangitis, the primary infection is in the tissue layers, not the lymphatic vessels themselves.

- Definition: Acute inflammation specifically of the lymphatic vessels.

- Appearance: Distinctive red streaks or lines extending from the infection site towards the lymph nodes. The streaks may be palpable and tender. The skin between the streaks may appear normal, or there may be accompanying cellulitis.

- Location: Within the lymphatic channels.

- Initiating Event: Usually originates from a localized infection (e.g., cut, abrasion, insect bite, wound, ingrown toenail, or even an area of cellulitis) that breaches the skin barrier, allowing bacteria to enter the lymphatic system.

These two conditions represent different aspects of lymphatic system pathology:

- Definition: A chronic condition characterized by the accumulation of protein-rich fluid in the interstitial space due to impaired lymphatic transport. It is a long-term swelling.

- Appearance: Persistent, progressive swelling of a body part (e.g., limb). The skin changes develop gradually over time (thickening, hardening, hyperkeratosis). It does not typically present with acute red streaks unless an acute infection (like cellulitis or lymphangitis) is superimposed.

- Etiology: Caused by primary (congenital) or secondary (e.g., surgery, radiation, filariasis) damage to the lymphatic system, leading to its inability to drain fluid effectively. It is a drainage problem.

- Onset: Usually gradual, though it can become apparent after an acute trigger (e.g., surgery).

- Symptoms: Heaviness, tightness, limb enlargement. Acute inflammatory signs are not characteristic unless infection is present.

- Definition: An acute infection and inflammation of the lymphatic vessels.

- Appearance: Acute red streaks, often with systemic signs of infection. It is an active infection and inflammation of the vessels, not a chronic fluid accumulation.

- Etiology: Caused by bacterial invasion of the lymphatic system. It is an infection problem.

- Onset: Rapid, acute.

- Symptoms: Red streaks, fever, chills, malaise.

Lymphangitis typically originates from a localized infection or injury that provides an entry point for bacteria into the lymphatic system. These initiating events can be quite varied:

- Skin Trauma/Breaks in the Skin Barrier:

- Cuts, Scrapes, Abrasions: Even minor skin injuries can allow bacteria to enter.

- Puncture Wounds: Including insect bites or stings, animal scratches or bites, splinters, or thorns.

- Surgical Wounds: Post-operative incisions can become infected.

- Burns: Especially if skin integrity is compromised.

- Blisters and Ulcers: Both venous and arterial ulcers, or even friction blisters, can be entry points.

- Tinea Pedis (Athlete's Foot): Fungal infections of the feet create cracks and fissures that bacteria can exploit.

- Ingrown Toenails: Can lead to localized infection and subsequent lymphangitis.

- Body Piercings/Tattoos: If not done or cared for aseptically.

- Existing Skin Infections:

- Cellulitis: A pre-existing cellulitis can extend into the lymphatic vessels.

- Abscesses or Boils: Localized collections of pus.

- Infected Wounds: Any wound that has become colonized with bacteria.

The vast majority of bacterial lymphangitis cases are caused by common skin bacteria.

- Streptococcus pyogenes (Group A Streptococcus - GAS):

- Most Common Cause: This bacterium is a frequent cause of both cellulitis and lymphangitis. It produces enzymes (e.g., hyaluronidase) that facilitate its rapid spread through tissues, including lymphatic channels.

- Staphylococcus aureus (including MRSA):

- Another Common Cause: While often associated with more localized infections like abscesses and boils, S. aureus can also cause diffuse cellulitis and lymphangitis. Methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) is an important consideration due to its antibiotic resistance.

- Other Bacteria:

- Less commonly, other bacteria can be involved, especially in specific circumstances:

- Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Often associated with water exposure or puncture wounds through footwear.

- Pasteurella multocida: From animal bites (cats, dogs).

- Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae: Associated with handling fish, meat, or poultry (causes erysipeloid, a specific type of localized skin infection that can be followed by lymphangitis).

- Anaerobes: In deep or necrotic wounds.

- Less commonly, other bacteria can be involved, especially in specific circumstances:

- Compromised Lymphatic System (Most Significant Risk Factor):

- Lymphedema (Primary or Secondary): Patients with pre-existing lymphedema have a severely impaired lymphatic drainage system. This leads to the accumulation of protein-rich fluid in the interstitial space, which acts as an excellent culture medium for bacteria. The damaged lymphatic vessels are also less able to clear pathogens. Recurrent infections are a hallmark complication of lymphedema.

- Prior Lymph Node Dissection: E.g., axillary dissection for breast cancer, inguinal dissection for melanoma.

- Radiation Therapy: To lymph node regions.

- Surgery: Any surgery that potentially damages lymphatic vessels.

- Immunocompromised States:

- Diabetes Mellitus: Impairs immune function, reduces circulation, and can lead to neuropathy, increasing risk of skin injury.

- HIV/AIDS: Compromises the overall immune system.

- Corticosteroid Use: Suppresses immune response.

- Chemotherapy: Can lead to immunosuppression.

- Chronic Kidney Disease/End-Stage Renal Disease: Often associated with immune dysfunction.

- Malnutrition: Can impair immune function.

- Impaired Venous Circulation:

- Chronic Venous Insufficiency (CVI): Can lead to venous stasis, skin breakdown (venous ulcers), and local edema, making the skin more vulnerable to infection and hindering immune response.

- Peripheral Arterial Disease (PAD): Reduces blood flow, impairing wound healing and immune response.

- Breaks in Skin Integrity (as mentioned above): Any condition that makes the skin less intact increases risk.

- Obesity: Associated with impaired lymphatic function, chronic inflammation, and increased skin fold areas which can be prone to maceration and fungal infections (further compromising skin barrier).

- Fungal Infections: Tinea Pedis (Athlete's Foot): Creates skin fissures that serve as entry points for bacteria.

- Poor Hygiene: Can contribute to increased bacterial load on the skin.

- Trauma/Injury: Repetitive micro-trauma or significant injury to a limb can increase susceptibility.

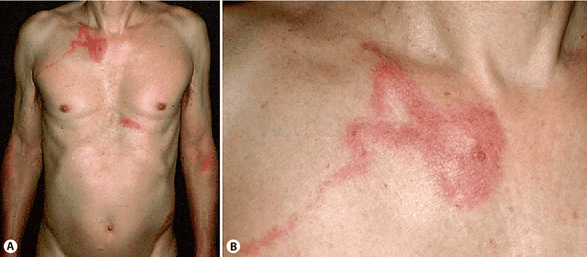

The hallmark of lymphangitis lies in its distinctive local presentation:

- Red Streaks (Linear Erythema):

- Description: This is the most characteristic and diagnostic sign. One or more fine, red lines or streaks appear on the skin.

- Location/Direction: These streaks typically extend from the initial site of infection (e.g., a cut, wound, or patch of cellulitis) proximally (away from the injury, towards the body's core) along the course of the superficial lymphatic vessels. For example, from an infected finger up the arm towards the axilla, or from an infected toe up the leg towards the groin.

- Appearance: The streaks are often slightly raised, tender to the touch, and warm. The skin between the streaks may appear normal, or there may be diffuse erythema if concurrent cellulitis is present.

- Tenderness and Pain: The affected lymphatic channels are usually quite tender and painful to palpation along the course of the red streaks.

- Warmth: Increased local skin temperature along the streaks due to the inflammatory process.

- Swelling (Edema): Localized swelling may be present around the initial infection site. The affected limb or area may also become diffusely swollen if concurrent cellulitis develops or if the lymphatic system is significantly compromised.

- Initial Site of Infection: Often, there is an identifiable primary lesion where the bacteria entered. This could be a small cut, abrasion, insect bite, wound, ingrown toenail, or an area of cellulitis. This primary site will typically show signs of inflammation (redness, swelling, warmth, pain) and sometimes pus or exudate.

- Lymphadenitis (Inflammation of Lymph Nodes):

- Description: The lymph nodes that drain the affected area (regional lymph nodes) frequently become enlarged, tender, and firm. For example, in an arm infection, axillary lymph nodes (in the armpit) would be affected; for a leg infection, inguinal lymph nodes (in the groin) would be involved.

- Significance: This indicates that the infection has reached the lymph nodes and they are actively trying to filter and contain the pathogens.

Lymphangitis is not just a localized skin condition; the presence of infection within the lymphatic system often triggers a systemic inflammatory response.

- Fever: Often high-grade (e.g., 101°F/38.3°C or higher).

- Chills and Rigors: Sudden onset of shivering and sensations of cold, often preceding or accompanying a spike in fever.

- Malaise: A general feeling of discomfort, illness, or uneasiness; feeling "unwell."

- Fatigue: Profound tiredness and lack of energy.

- Headache: Common accompanying symptom of systemic infection.

- Anorexia: Loss of appetite.

- Myalgia: Generalized muscle aches and pains.

- The local red streaks can appear quite rapidly after the initial infection, sometimes within hours.

- Systemic symptoms (fever, chills) often develop concurrently with or shortly after the appearance of the red streaks.

- If untreated, the infection can spread further, potentially leading to bacteremia (bacteria in the bloodstream) and sepsis (a life-threatening response to infection), or it can cause significant damage to the lymphatic system, exacerbating or initiating lymphedema.

- In rare, severe cases, the affected lymphatic vessels can become necrotic or abscessed.

- Breach of Skin Barrier: The process begins when the skin's protective barrier is compromised. This can be through a cut, scrape, insect bite, surgical incision, or even a pre-existing skin condition like athlete's foot or an ulcer.

- Bacterial Inoculation: Pathogenic bacteria, most commonly Streptococcus pyogenes or Staphylococcus aureus, gain entry into the superficial layers of the skin (dermis and subcutaneous tissue).

- Local Infection and Inflammation: The bacteria begin to multiply at the entry site, leading to a localized infection (e.g., a small cellulitis, abscess, or infected wound). The body's initial immune response triggers local inflammation, characterized by redness, warmth, swelling, and pain.

- Proximity to Lymphatics: The superficial lymphatic capillaries form a dense network just beneath the skin's surface, intertwining with blood capillaries.

- Lack of Basement Membrane: Unlike blood capillaries, lymphatic capillaries typically lack a continuous basement membrane and have highly permeable, overlapping endothelial cells (often referred to as "flap valves"). This structural feature allows them to readily absorb interstitial fluid, proteins, cells, and, critically, pathogens from the tissue spaces.

- Bacterial Entry into Lymphatics: As bacteria multiply and inflammation increases, the bacteria, along with inflammatory exudate, can easily enter these highly permeable lymphatic capillaries. This is often facilitated by bacterial enzymes (e.g., hyaluronidase produced by Streptococcus) that break down connective tissue, making it easier for them to spread.

- Upstream Transport: Once inside the lymphatic capillaries, bacteria are transported by the normal flow of lymph fluid. This flow is unidirectional, moving from the periphery towards the central lymphatic system.

- Inflammation of Collecting Vessels: As the bacteria and toxins travel, they initiate an inflammatory reaction within the walls of the larger, collecting lymphatic vessels. This inflammation involves:

- Vasodilation: Widening of the lymphatic vessels.

- Increased Permeability: Leakage of fluid and inflammatory cells (neutrophils, macrophages) into the vessel wall and surrounding tissue.

- Lymphatic Spasm/Obstruction: The acute inflammation can cause spasm and temporary obstruction of the lymphatic vessels, further impeding lymph flow and potentially contributing to local swelling.

- Visible Red Streaks: The inflammation of these superficial collecting lymphatic vessels makes them visible as the characteristic red streaks on the skin. The redness is due to the vasodilation and hyperemia (increased blood flow) in the vessels and the surrounding inflamed tissue. The streaks follow the anatomical course of the lymphatic drainage.

- Lymphangitis: This acute inflammatory process of the lymphatic vessels themselves is the definition of lymphangitis.

- Filtration and Immune Response: The lymphatic system includes lymph nodes strategically positioned along the lymphatic pathways. These nodes act as filters, trapping bacteria, cellular debris, and foreign particles.

- Lymphadenitis: When the bacteria reach the regional lymph nodes, they trigger a significant immune response. The nodes become inflamed, enlarged, tender, and sometimes painful – a condition known as lymphadenitis. This is a protective mechanism, attempting to localize and destroy the infection before it can spread further.

- Potential for Abscess Formation: In some cases, if the bacterial load is high or the immune response is overwhelmed, the lymph nodes can become severely infected and form abscesses.

- Release of Inflammatory Mediators: As the infection progresses and the immune system responds, inflammatory mediators (e.g., cytokines, prostaglandins) are released into the bloodstream.

- Systemic Symptoms: These mediators are responsible for the systemic signs of infection, such as fever, chills, malaise, headache, and myalgia.

- Risk of Bacteremia and Sepsis: If the regional lymph nodes are unable to contain the infection, or if the bacterial load is overwhelming, bacteria can escape the lymph nodes and enter the general circulation (bloodstream).

- Bacteremia: Presence of bacteria in the blood.

- Sepsis: A life-threatening systemic inflammatory response to infection, potentially leading to organ dysfunction.

- Lymphatic Damage: Repeated or severe episodes of lymphangitis can cause permanent damage to the lymphatic vessels and valves. This chronic damage can lead to impaired lymphatic drainage and contribute to the development or worsening of secondary lymphedema.

Diagnosing lymphangitis primarily relies on a thorough clinical assessment, as its characteristic presentation is quite distinctive.

This is the cornerstone of diagnosing lymphangitis.

- Patient History:

- Recent Skin Trauma/Breach: Inquire about any recent cuts, scrapes, insect bites, puncture wounds, surgical incisions, or skin lesions (e.g., athlete's foot, blisters) that could have served as an entry point for bacteria.

- Onset and Progression of Symptoms: Ask when the redness, pain, and systemic symptoms began and how they have evolved.

- Systemic Symptoms: Document the presence and severity of fever, chills, malaise, headache, and fatigue.

- Past Medical History: Specifically inquire about predisposing factors such as a history of lymphedema, diabetes, immunosuppression, or previous episodes of cellulitis/lymphangitis.

- Travel History: (Less common, but relevant for unusual pathogens).

- Physical Examination:

- Inspection:

- Red Streaks: Look for the characteristic red, linear streaks extending proximally from a suspected primary infection site towards the regional lymph nodes. Note their number, length, and distribution.

- Primary Infection Site: Identify and assess the initial source of infection (e.g., wound, abrasion, cellulitis). Note signs of inflammation, pus, or other discharge.

- Skin Condition: Assess the overall skin condition of the affected limb, noting any signs of lymphedema (thickening, non-pitting edema), prior skin damage, or concurrent cellulitis.

- Palpation:

- Tenderness/Pain: Gently palpate along the red streaks to assess for tenderness and induration (hardening).

- Warmth: Assess for increased warmth over the affected area.

- Regional Lymph Nodes: Carefully palpate the lymph nodes draining the affected area (e.g., axillary nodes for arm involvement, inguinal nodes for leg involvement). Assess for enlargement, tenderness, and consistency (firmness).

- Vital Signs: Monitor for fever, tachycardia, and other signs of systemic inflammatory response.

- Inspection:

These are primarily used to confirm the presence and severity of infection and guide antibiotic therapy.

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) with Differential:

- White Blood Cell (WBC) Count: Typically elevated (leukocytosis), often with a "left shift" (increase in immature neutrophils), indicating a bacterial infection.

- Inflammatory Markers:

- Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) and C-Reactive Protein (CRP): These will usually be elevated, indicating systemic inflammation. While non-specific, they can be useful for monitoring response to treatment.

- Blood Cultures:

- Purpose: To identify the causative organism and determine its antibiotic susceptibility, especially if the patient is severely ill, septic, or immunocompromised, or if the infection is not responding to empiric antibiotics.

- When to Obtain: Should be drawn before initiating antibiotic therapy.

- Yield: Positive blood cultures are relatively uncommon in uncomplicated lymphangitis (estimated <10%), as the infection may be localized to the lymphatic system without true bacteremia.

- Wound/Swab Culture (from primary infection site):

- Purpose: If there is an obvious primary lesion with purulent drainage, a culture of the exudate can help identify the pathogen and guide antibiotic selection.

- Consideration: Surface cultures may not always reflect the deep tissue pathogen.

Imaging studies are usually reserved for atypical presentations, to rule out other conditions, or to assess for complications.

- Ultrasound:

- Purpose: Can be used to rule out underlying abscess formation, deep vein thrombosis (DVT) in the leg (which can present with redness and swelling), or to evaluate for fluid collections. It can also visualize dilated lymphatic channels in severe cases.

- Utility: Useful if the diagnosis is unclear or if complications are suspected.

- CT Scan or MRI:

- Purpose: Rarely needed for uncomplicated lymphangitis. May be used in complex cases to delineate deeper infection, rule out osteomyelitis, or assess for extensive abscess formation, especially in the context of sepsis or failure to respond to treatment.

- Lymphoscintigraphy/Indocyanine Green (ICG) Lymphography:

- Purpose: These are specialized tests used to assess lymphatic function and anatomy, primarily in the diagnosis and staging of lymphedema. They are not used for acute diagnosis of lymphangitis. However, they can be relevant retrospectively to assess lymphatic damage after recurrent episodes of lymphangitis, or to identify pre-existing lymphedema that predisposed the patient to lymphangitis.

It's important to consider other conditions that might mimic lymphangitis:

- Cellulitis: Often coexists, but diffuse redness without streaks suggests primary cellulitis.

- Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT): Can cause acute limb pain, swelling, and redness, but typically lacks the characteristic streaks and fever may be absent.

- Erysipelas: A superficial form of cellulitis with sharply demarcated, raised borders, often on the face or lower extremities.

- Contact Dermatitis: Allergic reaction causing redness and itching, usually without systemic symptoms or linear streaks of infection.

- Tendonitis/Phlebitis: Local inflammation of tendons or veins can cause pain and some redness, but generally not the distinct streaking.

Goals of management of lymphangitis is to halt the spread of infection, alleviate symptoms, prevent complications, and preserve lymphatic function.

The prompt initiation of appropriate antibiotics is the cornerstone of lymphangitis treatment. The choice of antibiotic is initially empiric, targeting the most common causative organisms (Streptococcus pyogenes and Staphylococcus aureus), and may be adjusted based on culture results and susceptibility testing if available.

- Empiric Antibiotic Selection:

- Coverage: Should cover both Group A Streptococci and Staphylococcus aureus.

- Common Choices:

- Oral: For mild to moderate cases in outpatient settings:

- Penicillinase-resistant penicillins (e.g., dicloxacillin).

- First-generation cephalosporins (e.g., cephalexin).

- Clindamycin (if penicillin allergy or suspected MRSA).

- Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) or doxycycline (if MRSA is strongly suspected, but less reliable for strep).

- Intravenous (IV): For severe cases, rapidly progressing infection, systemic toxicity, failure of oral therapy, or immunocompromised patients, requiring hospitalization:

- Beta-lactam antibiotics (e.g., cefazolin, ceftriaxone, nafcillin, oxacillin).

- Vancomycin (if MRSA is suspected or confirmed, or in penicillin-allergic patients).

- Clindamycin.

- Oral: For mild to moderate cases in outpatient settings:

- Duration: Typically 7-14 days, depending on the severity of the infection and clinical response. Treatment should continue until all signs of infection have resolved and for at least a few days after.

- Adjusting Therapy:

- If blood cultures or wound cultures yield a specific pathogen and susceptibility results are available, the antibiotic regimen can be narrowed (de-escalated) to a more targeted and potentially less broad-spectrum agent.

- Analgesics: Over-the-counter pain relievers such as acetaminophen or NSAIDs (ibuprofen, naproxen) for mild to moderate pain. Stronger analgesics may be prescribed for severe pain.

Supportive care measures are vital for patient comfort, reducing inflammation, promoting healing, and preventing complications.

- Rest and Elevation:

- Intervention: Encourage rest for the affected limb and elevate it above the level of the heart (e.g., using pillows).

- Rationale: Reduces swelling, decreases pain, and promotes lymphatic and venous drainage.

- Immobilization (if severe):

- Intervention: In severe cases, temporary immobilization of the affected limb may be beneficial.

- Rationale: Reduces movement that could exacerbate pain and inflammation.

- Warm or Cool Compresses (Controversial, use with caution):

- Intervention: Some sources suggest warm compresses for comfort and vasodilation; others suggest cool compresses for inflammation. Use carefully.

- Rationale: Warmth can increase circulation and may aid in reabsorption of fluid, but excessive heat can also increase inflammation or macerate skin. Cool compresses can reduce local inflammation and pain. Crucially, avoid anything that can damage already compromised skin.

- Skin Care and Infection Control:

- Intervention: Meticulous skin hygiene at the primary infection site and surrounding areas. Keep the area clean and dry. Avoid harsh soaps or rubbing.

- Rationale: Prevents further bacterial invasion, promotes healing, and reduces the risk of secondary infections.

- Hydration:

- Intervention: Encourage adequate oral fluid intake; IV fluids may be necessary for hospitalized patients, especially if febrile or vomiting.

- Rationale: Prevents dehydration, supports immune function, and helps eliminate toxins.

- Monitoring for Complications:

- Intervention: Closely monitor vital signs (temperature, pulse, blood pressure), assess for worsening redness, swelling, pain, spread of streaks, or signs of abscess formation. Monitor for signs of systemic toxicity (e.g., confusion, rapid breathing, hypotension).

- Rationale: Early detection and intervention for complications like abscess, sepsis, or worsening infection.

- Patient Education:

- Intervention: Educate the patient on:

- The importance of completing the full course of antibiotics, even if symptoms improve.

- Signs and symptoms of worsening infection (e.g., increased fever, spreading redness, pus, new pain) and when to seek immediate medical attention.

- Strategies for preventing future episodes: meticulous skin care, prompt treatment of skin breaks, avoiding trauma, treating underlying conditions like tinea pedis, and managing lymphedema if present.

- The chronic nature of lymphedema and its role as a risk factor for recurrent infections.

- Rationale: Empowers the patient to manage their condition, adhere to treatment, and prevent recurrence.

- Intervention: Educate the patient on:

- Management of Underlying Conditions:

- Intervention: Address any predisposing factors, such as aggressive management of diabetes, treatment of tinea pedis, or ongoing lymphedema management.

- Rationale: Reduces the risk of future episodes.

- Prophylactic Antibiotics (in selected cases):

- Intervention: For individuals with recurrent episodes of lymphangitis/cellulitis, especially those with lymphedema, a physician may consider long-term low-dose prophylactic antibiotics.

- Rationale: To prevent future infections, given the high risk of recurrence and potential for further lymphatic damage.

While often treatable with antibiotics, lymphangitis can lead to severe and potentially life-threatening complications if left untreated, if the patient is immunocompromised, or if it becomes a recurrent issue. These complications can affect both general health and the long-term integrity of the lymphatic system.

- Abscess Formation:

- Mechanism: If the infection is not effectively controlled, bacteria can become localized, leading to the destruction of tissue and the formation of a collection of pus (abscess) within the lymphatic vessels or surrounding tissues, or even within the regional lymph nodes.

- Consequences: Requires surgical drainage in addition to antibiotics. Can delay healing and cause more extensive tissue damage.

- Bacteremia and Sepsis:

- Mechanism: If the infection overwhelms the local immune defenses and regional lymph nodes, bacteria can enter the bloodstream (bacteremia). This can trigger a widespread, dysregulated inflammatory response throughout the body (sepsis).

- Consequences: Sepsis is a life-threatening condition that can lead to septic shock, multi-organ dysfunction (e.g., acute kidney injury, respiratory failure), and death. Prompt recognition and aggressive treatment are critical.

- Septic Thrombophlebitis:

- Mechanism: Infection and inflammation of a vein wall that leads to thrombus (clot) formation within the vein, often localized to the area of infection.

- Consequences: Can cause localized pain and swelling. Rarely, the clot can break off and travel to the lungs (pulmonary embolism), though this is more common with deep vein thrombosis.

- Osteomyelitis:

- Mechanism: In rare cases, especially with deep puncture wounds or infections close to bone, the infection can spread directly or hematogenously to the bone, causing bone infection.

- Consequences: Difficult to treat, often requiring prolonged antibiotic therapy and sometimes surgical debridement.

- Endocarditis:

- Mechanism: If bacteria enter the bloodstream (bacteremia), they can travel to the heart and infect the heart valves, particularly in individuals with pre-existing heart valve abnormalities.

- Consequences: Serious heart condition that can lead to valve damage, heart failure, and systemic emboli.

- Chronic Lymphedema:

- Mechanism: This is arguably the most significant long-term complication of recurrent lymphangitis. Each episode of acute inflammation and infection within the lymphatic vessels can cause permanent damage to the delicate lymphatic capillaries and collecting vessels. This damage can include scarring, fibrosis, and destruction of the lymphatic valves, leading to impaired lymphatic transport capacity.

- Consequences: Accumulation of protein-rich fluid in the interstitial space, resulting in chronic swelling, skin thickening, fibrosis, and increased susceptibility to further infections. This creates a vicious cycle where lymphedema predisposes to lymphangitis, which in turn worsens lymphedema.

- Recurrent Cellulitis/Lymphangitis:

- Mechanism: Damaged lymphatic vessels and compromised lymphatic drainage (due to developing lymphedema) create a favorable environment for bacterial proliferation. The skin often becomes thicker, drier, and more prone to minor trauma, providing more entry points for bacteria.

- Consequences: Patients can experience frequent, debilitating episodes of infection, requiring repeated antibiotic courses and hospitalizations, significantly impacting quality of life.

- Skin Changes (Chronic Venous-Lymphatic Insufficiency):

- Mechanism: Chronic inflammation and fluid accumulation can lead to irreversible skin changes, often seen in the context of chronic lymphedema or venous insufficiency.

- Consequences:

- Hyperkeratosis: Thickening of the outer layer of the skin.

- Papillomatosis: Development of small, wart-like growths.

- Fissures and Cracks: Increased susceptibility to skin breakdown.

- Pigmentation Changes: Discoloration of the skin.

- Dermatoliposclerosis: Hardening and thickening of the skin and subcutaneous tissues.

- Impaired Quality of Life:

- Mechanism: Chronic pain, recurrent infections, fear of infection, physical disfigurement, and functional limitations from lymphedema can significantly impact psychological well-being, social activities, and daily living.

Prevention is paramount in managing lymphangitis, particularly in individuals prone to recurrent episodes.

- Keep Skin Clean and Moisturize:

- Intervention: Wash skin daily with mild soap, rinse thoroughly, and pat dry. Apply a pH-neutral, unscented moisturizer daily to prevent dryness and cracking.

- Rationale: Clean skin reduces bacterial load. Moisturizing maintains skin barrier integrity, preventing fissures and dryness that can serve as entry points for bacteria.

- Prompt Treatment of Skin Breaks:

- Intervention: Any cut, scrape, insect bite, blister, or skin lesion, no matter how small, should be thoroughly cleaned with soap and water and covered with a clean, sterile dressing. Apply antiseptic cream if advised by a healthcare professional.

- Rationale: Minimizes the opportunity for bacteria to enter the lymphatic system.

- Foot Care (especially important for diabetics and lymphedema patients):

- Intervention: Inspect feet daily for cuts, blisters, athlete's foot (tinea pedis), or other abnormalities. Wear clean, properly fitting shoes and socks. Treat tinea pedis aggressively with antifungal medications.

- Rationale: Feet are common sites for initial infections, especially with conditions like athlete's foot which create entry points. Good foot care prevents these entry points.

- Nail Care:

- Intervention: Trim fingernails and toenails carefully to avoid nicks or ingrown nails. Do not cut cuticles.

- Rationale: Prevents small wounds that can become infected.

- Protect Skin from Injury:

- Intervention: Wear gloves for gardening, housework, or other activities that might cause skin trauma. Use insect repellent to prevent bites. Be cautious with sharp objects.

- Rationale: Directly prevents breaches in the skin barrier.

- Avoid Constriction:

- Intervention: Avoid tight clothing, jewelry, or blood pressure cuffs on an affected limb (especially if at risk for lymphedema).

- Rationale: Constriction can further impair lymphatic flow, potentially increasing local tissue pressure and susceptibility to infection.

- Lymphedema Management:

- Intervention: For individuals with lymphedema, strict adherence to a comprehensive lymphedema management plan is crucial. This includes:

- Manual Lymphatic Drainage (MLD): Performed by a trained therapist.

- Compression Therapy: Wearing compression garments (sleeves, stockings, wraps) daily.

- Exercise: Specific exercises to promote lymph flow.

- Meticulous Skin Care: As described above, paramount for lymphedema patients.

- Rationale: Effective lymphedema management reduces fluid accumulation, improves lymphatic function, and strengthens the skin barrier, thereby significantly reducing the risk of recurrent infections.

- Intervention: For individuals with lymphedema, strict adherence to a comprehensive lymphedema management plan is crucial. This includes:

- Control of Chronic Diseases:

- Intervention: For conditions like diabetes, strict blood glucose control is essential. Manage chronic venous insufficiency and other conditions that compromise skin integrity or immune function.

- Rationale: Improves overall immune response, circulation, and tissue health, making the body more resilient to infection.

- Treatment of Fungal Infections:

- Intervention: Promptly treat any fungal infections (e.g., tinea pedis, candidiasis) with appropriate antifungal agents.

- Rationale: Fungal infections can create cracks and fissures in the skin, providing entry points for bacteria.

- Consideration for Recurrent Episodes:

- Intervention: In patients who experience frequent, severe, or rapidly recurrent episodes of lymphangitis (e.g., 2-3 episodes per year), especially those with underlying lymphedema, a healthcare provider may consider a course of long-term, low-dose prophylactic antibiotics.

- Common Regimens: Oral penicillin V, erythromycin, or dicloxacillin.

- Rationale: While not without risks (e.g., antibiotic resistance, side effects), prophylactic antibiotics can significantly reduce the frequency of infections in highly susceptible individuals, preventing further lymphatic damage and improving quality of life. This decision should be made in consultation with an infectious disease specialist or an experienced clinician.

- Awareness and Early Recognition:

- Intervention: Educate patients about the signs and symptoms of lymphangitis and emphasize the importance of seeking medical attention at the first sign of infection.

- Rationale: Early treatment can prevent the infection from escalating and causing more damage.

- Adherence to Treatment and Prevention Plans:

- Intervention: Reinforce the importance of consistently following all prescribed treatments and preventive measures.

- Rationale: Consistency is key to long-term prevention.

Nursing Diagnosis: Acute Pain related to inflammatory process in lymphatic vessels and surrounding tissues, as evidenced by patient's verbal reports of pain, grimacing, guarding behavior, and tenderness on palpation.

Goals: Patient will report reduced pain level (e.g., from 8/10 to 3/10) within a specified timeframe, and demonstrate relaxed posture and facial expression.

| Nursing Interventions | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Assess pain characteristics: Ask patient to rate pain on a 0-10 scale, describe location, quality (e.g., throbbing, aching), and radiating patterns. | Provides baseline data, helps monitor effectiveness of interventions, and guides appropriate pain management. |

| Administer prescribed analgesics: Provide pain medication (e.g., NSAIDs, acetaminophen, opioids if indicated) as ordered, and evaluate effectiveness after administration. | Pharmacological pain relief is essential to manage acute inflammation and discomfort. |

Implement non-pharmacological pain relief measures:

|

|

| Educate patient on pain management techniques: Discuss the importance of reporting pain, medication schedules, and proper use of elevation/compresses. | Empowers patient in their own pain management and promotes adherence. |

Nursing Diagnosis: Impaired Skin Integrity related to inflammatory process, edema, and potential for skin breakdown at the primary infection site, as evidenced by redness, warmth, tenderness, and presence of an open wound/lesion.

Goals: Patient will demonstrate improved skin integrity, free from further breakdown, and the primary lesion will show signs of healing.

| Nursing Interventions | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Assess skin integrity regularly: Inspect the affected area and the primary infection site for changes in redness, warmth, swelling, presence of discharge, cracks, or signs of breakdown. | Early detection of worsening conditions or new areas of damage allows for timely intervention. |

| Perform meticulous wound care (if applicable): Clean the primary lesion as prescribed (e.g., with mild soap and water or antiseptic), and apply appropriate dressings. | Prevents further bacterial invasion, promotes healing, and protects the wound from external contaminants. |

| Maintain skin hygiene: Cleanse the entire affected limb gently with mild soap and water, and pat dry thoroughly. | Reduces bacterial load on the skin surface, minimizing risk of secondary infection. |

| Apply moisturizer: Use a neutral pH, unscented moisturizer daily to intact skin, avoiding open lesions. | Maintains skin hydration and elasticity, preventing dryness and cracking which can be entry points for bacteria. |

| Protect skin from trauma: Advise patient to avoid scratching, wearing tight clothing or jewelry, and to use caution with sharp objects. | Prevents further damage to already compromised or vulnerable skin. |

| Monitor for signs of cellulitis or abscess formation: Observe for spreading redness, increased warmth, induration, or fluctuance. | These are signs of worsening infection requiring prompt medical attention. |

Nursing Diagnosis: Risk for Infection (spread or recurrence) related to compromised lymphatic system, presence of pathogenic organisms, and potential for ineffective health management.

Goals: Patient will remain free from signs of worsening infection (e.g., no spread of red streaks, no new fever), and will verbalize understanding of prevention strategies for recurrence.

| Nursing Interventions | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Administer prescribed antibiotics: Ensure timely administration of antibiotics as ordered and monitor for side effects or allergic reactions. | Directly targets the causative bacteria, halting the infection's progression. |

| Monitor vital signs and lab results: Regularly check temperature for fever spikes, and review WBC count, CRP, and ESR. | Provides objective data on the body's inflammatory response and helps assess effectiveness of antibiotic therapy. |

| Observe for signs of infection spread: Closely monitor the extent of red streaks, new areas of redness, increased pain, or development of purulent drainage from the primary site or lymph nodes. | Early detection of spread allows for timely modification of treatment. |

| Educate patient on completing antibiotic course: Emphasize the importance of taking all prescribed antibiotics, even if symptoms improve, and explain the risks of stopping early. | Prevents antibiotic resistance and ensures complete eradication of the infection, reducing risk of recurrence. |

Patient education on prevention strategies (as detailed in Objective 8):

|

Empowers patient for early self-detection and prompt treatment, preventing severe episodes. |

| Discuss signs of recurrence: Teach patient what to look for and when to seek medical help (e.g., new redness, fever, pain). | Empowers patient for early self-detection and prompt treatment, preventing severe episodes. |

Nursing Diagnosis: Inadequate health Knowledge regarding disease process, treatment regimen, and prevention strategies related to lack of exposure or unfamiliarity with lymphangitis.

Goals: Patient will verbalize understanding of lymphangitis, its treatment, and at least three prevention strategies for recurrence.

| Nursing Interventions | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Assess patient's current knowledge level: Ask open-ended questions about what they know regarding their condition. | Identifies knowledge gaps and allows for individualized teaching. |

| Provide clear, concise information: Explain lymphangitis in simple terms, using visual aids if helpful. Cover causes, symptoms, diagnosis, treatment (antibiotics, supportive care), and potential complications. | Improves patient's understanding and reduces anxiety. |

| Educate on prescribed medications: Explain purpose, dosage, schedule, potential side effects, and importance of completing the full course. | Promotes medication adherence and safe use. |

| Teach preventive measures comprehensively: Review all points under "Risk for Infection" interventions, including skin care, trauma avoidance, lymphedema management, and recognizing early signs of recurrence. | Equips patient with tools to prevent future episodes. |

| Encourage questions and provide opportunities for return demonstration: Allow patient to ask questions and, if appropriate (e.g., wound care), demonstrate techniques. | Reinforces learning and ensures comprehension. |

| Provide written educational materials: Handouts or links to reliable online resources. | Serves as a reference and reinforces verbal instructions. |

Nursing Diagnosis: Impaired Physical Mobility related to pain and swelling in the affected limb, as evidenced by reluctance to move, decreased range of motion, and verbal reports of discomfort with movement.

Goals: Patient will maintain optimal physical mobility, demonstrate ability to perform activities of daily living (ADLs) with minimal assistance, and verbalize methods to protect the affected limb during movement.

| Nursing Interventions | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Assess current mobility level and limitations: Determine how pain and swelling affect ambulation and ADLs. | Establishes a baseline for intervention planning. |

| Assist with ADLs as needed: Provide support for bathing, dressing, and other self-care activities. | Ensures patient's needs are met while minimizing strain on the affected limb. |

| Encourage gentle range-of-motion (ROM) exercises (if appropriate and not increasing pain): Once acute pain subsides, guide patient through gentle movements of unaffected joints and, if tolerated, very light movement of the affected limb. | Helps prevent joint stiffness, muscle weakness, and promotes circulation, but avoid exacerbating inflammation. |

| Emphasize proper positioning and elevation: Reinforce the importance of elevating the limb during rest. | Reduces edema, which can restrict movement. |

| Collaborate with physical therapy (if indicated): Refer for assessment and development of a tailored exercise program. | Professional guidance can optimize recovery of mobility and function. |

| Educate on safety during ambulation: If ambulating, ensure patient has appropriate footwear and uses assistive devices if necessary. | Prevents falls and injury to the affected limb. |