Osteoarthritis (OA) is a common, chronic, and progressive degenerative joint disease characterized by the breakdown and eventual loss of articular cartilage, which normally cushions the ends of bones.

Osteoarthritis is a type of arthritis that occurs when flexible tissue at the ends of bones wears down.

This cartilage degradation leads to bones rubbing directly against each other, causing pain, stiffness, and loss of movement. OA primarily affects the synovial joints and is often described as a "wear-and-tear" type of arthritis, though it's now understood to be a more complex process involving the entire joint, including the subchondral bone, synovium, and surrounding soft tissues.

- Degenerative: Involves the gradual deterioration of joint components.

- Non-inflammatory (primarily): While low-grade inflammation can occur in the synovium, it is not the primary driver of the disease, unlike RA.

- Progressive: Worsens over time, though the rate of progression varies.

- Mechanical Stress: Often associated with mechanical stress, joint injury, and aging.

It's crucial to understand the fundamental differences between OA and RA. While both cause joint pain and stiffness, their underlying pathology, clinical presentation, and management are distinct.

| Feature | Osteoarthritis (OA) | Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) |

|---|---|---|

| Type of Disease | Degenerative joint disease ("wear-and-tear" type) | Autoimmune, chronic inflammatory disease |

| Primary Pathology | Cartilage breakdown and loss; bone-on-bone friction | Synovial inflammation (synovitis) leading to pannus formation and joint destruction |

| Etiology | Multifactorial: age, genetics, obesity, joint injury, mechanical stress | Autoimmune response (genetic predisposition, environmental triggers) |

| Nature of Inflammation | Primarily non-inflammatory; localized, low-grade inflammation may occur in later stages | Significant, systemic, and persistent inflammation |

| Onset | Gradual, insidious, often developing over years | Often gradual, but can be acute/subacute; typically weeks to months |

| Joints Affected (Pattern) | Asymmetrical involvement; affects weight-bearing joints (knees, hips, spine), hands (DIP, PIP, CMC of thumb), feet (MTP). | Symmetrical involvement; affects small joints of hands (MCP, PIP), wrists, feet (MTP), shoulders, elbows, knees. Seldom affects DIP joints. |

| Morning Stiffness | Brief, typically < 30 minutes; improves with movement | Prolonged, typically > 30 minutes (often hours); worse after rest |

| Pain Pattern | Worse with activity and weight-bearing; relieved by rest; "end-of-day" pain | Worse at rest and in the morning; improves with activity |

| Systemic Symptoms | Absent (no fever, fatigue, malaise, weight loss) | Present (fatigue, malaise, low-grade fever, weight loss) |

| Joint Swelling | Hard, bony enlargement (osteophytes); sometimes effusions | Soft, boggy, warm, tender, symmetrical swelling |

| Joint Deformities | Bony enlargements (Heberden's/Bouchard's nodes in fingers); alignment issues (e.g., bow-legs) | Swan-neck, boutonnière, ulnar deviation, rheumatoid nodules |

| Laboratory Findings | Usually normal ESR/CRP; negative RF/anti-CCP | Elevated ESR/CRP; often positive RF/anti-CCP |

| Radiographic Findings | Joint space narrowing, osteophytes, subchondral sclerosis, cysts | Joint space narrowing, erosions, juxta-articular osteopenia |

| Treatment Focus | Pain management, functional improvement, preserving joint structure, lifestyle modifications | Suppressing inflammation, preventing joint destruction (DMARDs), managing symptoms |

OA can be broadly classified into two categories based on its etiology:

- Primary (Idiopathic) OA: The most common form, with no identifiable underlying cause other than general risk factors (e.g., aging, genetics). It typically involves multiple joints.

- Secondary OA: Occurs as a result of a known predisposing factor that directly damages cartilage or alters joint mechanics (e.g., trauma, inflammatory joint disease, metabolic disorders).

Regardless of classification, a variety of risk factors contribute to its development and progression:

- Obesity / Overweight:

- Mechanism: Increased mechanical stress on weight-bearing joints (knees, hips, spine). Adipose tissue also produces pro-inflammatory cytokines (adipokines) that contribute to systemic inflammation and cartilage degradation, suggesting a metabolic link beyond just mechanical stress.

- Impact: A strong, dose-dependent relationship exists. Even a modest weight loss can significantly reduce the risk and slow the progression of OA, especially in the knees.

- Joint Injury or Trauma:

- Mechanism: Acute injuries (e.g., meniscal tears, ligamentous injuries like ACL rupture, fractures involving joint surfaces) can directly damage cartilage or alter joint mechanics, leading to abnormal stress distribution and accelerated wear. This is often termed "post-traumatic OA."

- Impact: Can lead to early-onset OA, even decades after the initial injury.

- Occupational / Repetitive Joint Stress:

- Mechanism: Certain occupations or activities involving repetitive loading, kneeling, heavy lifting, or prolonged standing can increase mechanical stress on specific joints, accelerating cartilage breakdown.

- Examples: Construction workers, athletes (e.g., soccer, football, ballet dancers), and certain factory workers.

- Muscle Weakness (especially quadriceps):

- Mechanism: Weakness of muscles surrounding a joint (e.g., quadriceps weakness around the knee) can compromise joint stability and shock absorption, leading to increased stress on cartilage.

- Poor Posture and Biomechanics:

- Mechanism: Incorrect alignment or movement patterns can lead to uneven loading and stress distribution across joint surfaces.

- Nutritional Factors (Indirectly Modifiable):

- Mechanism: While not a direct cause, poor nutrition can affect overall joint health and inflammatory status.

- Impact: Maintaining a balanced diet supports general health, and managing weight through diet is crucial.

- Age:

- Mechanism: The strongest risk factor. Cartilage naturally degenerates with age, becoming less elastic, more susceptible to damage, and less able to repair itself. Chondrocyte function declines.

- Impact: OA prevalence significantly increases with age, especially after 40-50 years.

- Genetics / Heredity:

- Mechanism: Genetic predisposition plays a significant role, particularly in generalized OA (affecting multiple joints) and OA of specific joints (e.g., hand OA, hip OA). Genes can influence cartilage quality, bone structure, and inflammatory responses.

- Impact: If parents or close relatives have OA, an individual's risk is higher.

- Sex (Gender):

- Mechanism: OA is generally more common and often more severe in women, especially after menopause. Hormonal factors (e.g., estrogen deficiency) are thought to play a role, as is differing joint anatomy and biomechanics.

- Impact: Women have a higher incidence of knee and hand OA, while hip OA is more evenly distributed or slightly more common in men.

- Race / Ethnicity:

- Mechanism: Some racial/ethnic groups have different prevalence rates or patterns of OA, potentially due to genetic factors, body habitus, lifestyle, or environmental exposures.

- Impact: e.g., African Americans have a higher prevalence of knee OA but a lower prevalence of hip OA compared to Caucasians.

- Bone Density:

- Mechanism: Paradoxically, higher bone mineral density (BMD) has been associated with an increased risk of OA. This might be because stiffer bones are less able to absorb shock, transferring more stress to the cartilage.

- Congenital or Developmental Joint Abnormalities:

- Mechanism: Conditions present from birth or developing early in life that affect joint structure (e.g., hip dysplasia, Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease, congenital dislocation of the hip) can lead to abnormal joint mechanics and premature cartilage wear.

- Metabolic Disorders (Indirectly Modifiable in some cases):

- Mechanism: Certain conditions like diabetes, hemochromatosis (iron overload), and Wilson's disease (copper overload) can affect cartilage metabolism and increase OA risk. Crystal deposition diseases (e.g., gout, pseudogout) can also cause secondary OA.

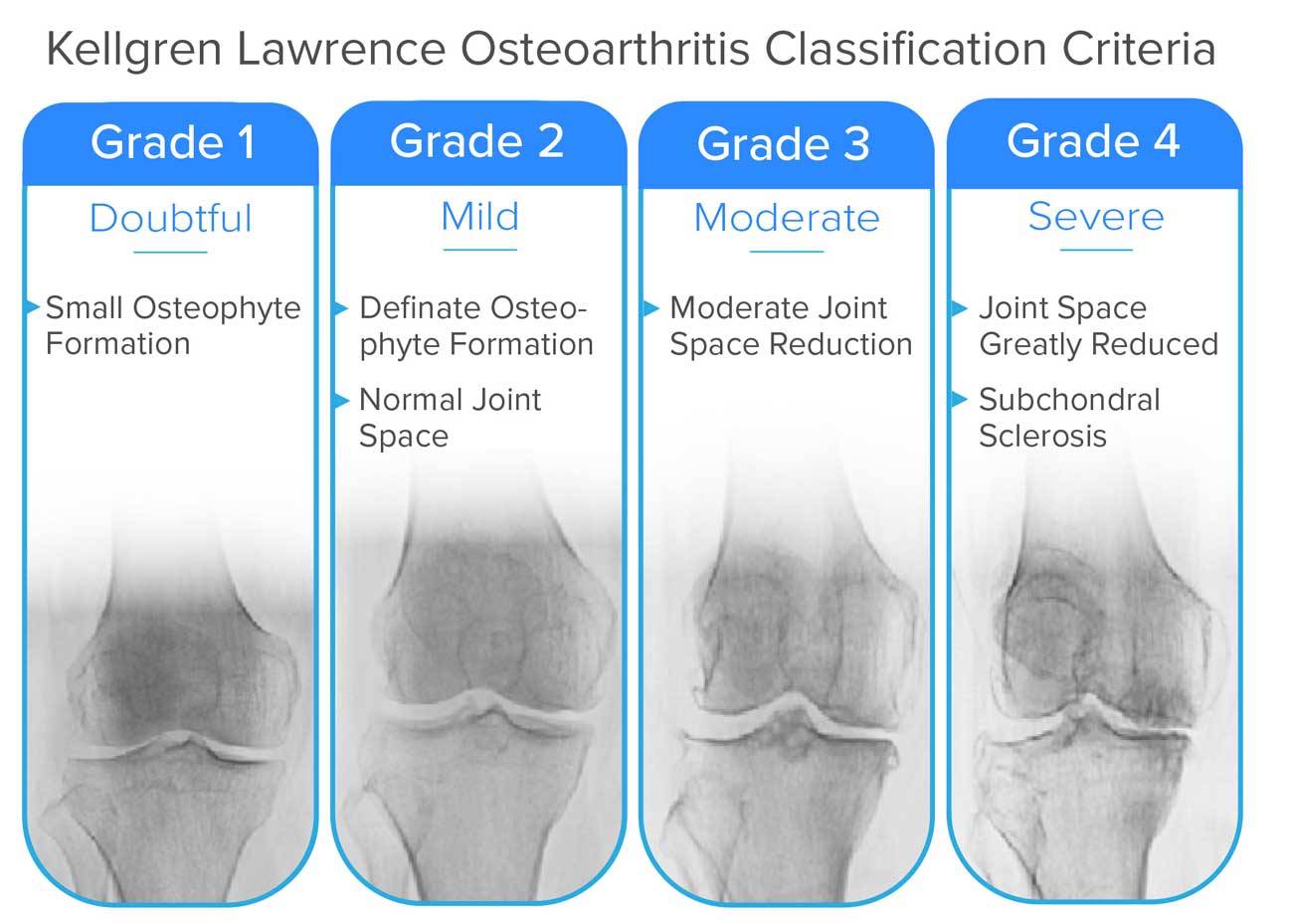

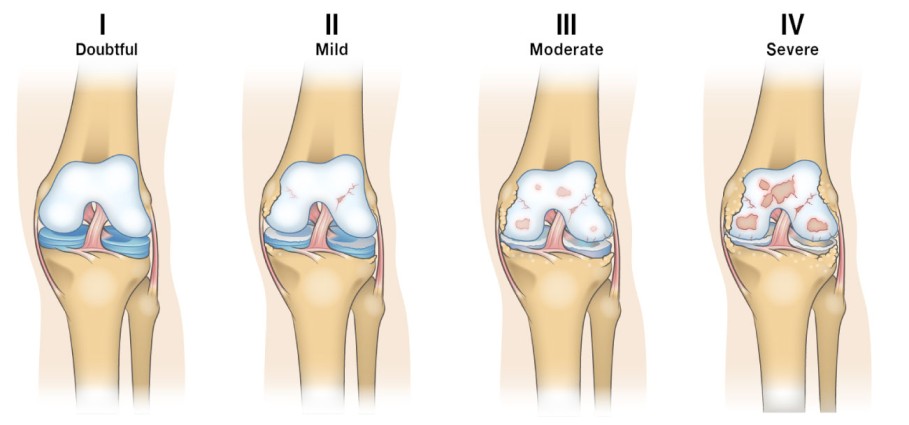

This system grades the severity of OA based on X-ray findings, ranging from 0 (no OA,) to 4 (severe OA).

There's a minimal presence of osteophytes (bone spurs) at the joint margins, but the joint space itself still appears normal or near normal. This grade might be difficult to definitively diagnose as OA.

- Key Radiographic Feature: Small Osteophyte Formation

Clear and distinct osteophytes are visible. However, despite the presence of bone spurs, the joint space between the bones is still largely preserved, indicating only early cartilage loss.

- Key Radiographic Features:

- Definite Osteophyte Formation

- Normal Joint Space

The joint space has clearly narrowed, indicating significant cartilage loss. Osteophytes are generally prominent.

- Key Radiographic Features:

- Moderate Joint Space Reduction

- Possibly also moderate osteophytes, some subchondral sclerosis, and cysts (though not explicitly listed as criteria in the image for this grade).

There is almost complete obliteration of the joint space, signifying extensive cartilage loss. The bone beneath the cartilage (subchondral bone) shows increased density (sclerosis) due to increased stress. Large osteophytes and sometimes noticeable bone deformity are present. This represents end-stage OA.

- Key Radiographic Features:

- Joint Space Greatly Reduced

- Subchondral Sclerosis

- Large Osteophytes

- Possible Subchondral Cysts and Bone Deformity

The pathophysiology of Osteoarthritis (OA) is a process involving the entire joint structure, not just passive "wear and tear" of cartilage.

Before understanding OA, it's helpful to recall the structure of healthy cartilage:

- Composition: Primarily composed of chondrocytes (cartilage cells) embedded in an extracellular matrix (ECM).

- ECM Components:

- Collagen fibers (Type II): Provide tensile strength.

- Proteoglycans (e.g., Aggrecan): Large molecules that trap water, giving cartilage its resilience and ability to withstand compressive forces.

- Water: Accounts for 65-80% of cartilage weight, crucial for shock absorption.

- Avascular and Aneural: Lacks blood vessels and nerves, making repair capacity limited and preventing pain sensation within the cartilage itself.

- Function: Provides a smooth, low-friction surface for joint movement and distributes load efficiently across the joint.

The development of OA is a cycle involving initial damage, repair attempts, and eventual failure of repair mechanisms, leading to progressive degeneration.

- Initial Triggers/Stressors:

- Mechanical stress (obesity, trauma, repetitive use, malalignment).

- Biochemical changes (aging, genetics, inflammatory mediators).

- These stressors disrupt the normal homeostasis of the chondrocytes and their surrounding ECM.

- Chondrocyte Activation and Dysregulation:

- Initially, chondrocytes respond to stress by attempting repair:

- They proliferate.

- They increase synthesis of matrix components (collagen, proteoglycans).

- However, this repair is often abnormal or insufficient, producing an inferior quality matrix.

- Over time, and with persistent stress, chondrocytes become dysfunctional:

- They switch from an anabolic (building) to a catabolic (breaking down) state.

- They produce pro-inflammatory mediators and degradative enzymes.

- Ultimately, they undergo apoptosis (programmed cell death), leading to a reduction in chondrocyte numbers.

- Initially, chondrocytes respond to stress by attempting repair:

- Extracellular Matrix (ECM) Degradation:

- Enzyme Production: Dysfunctional chondrocytes and synovial cells produce excessive amounts of proteolytic enzymes:

- Matrix Metalloproteinases (MMPs): A family of enzymes (e.g., collagenases, stromelysins) that break down collagen and proteoglycans.

- Aggrecanases (ADAMTS enzymes): Specifically degrade aggrecan.

- Proteoglycan Loss: The earliest biochemical change in OA is the breakdown and loss of aggrecan. This reduces the cartilage's water-binding capacity, making it less resilient and more susceptible to mechanical damage.

- Collagen Network Damage: As the disease progresses, the collagen (Type II) network is also degraded, leading to further structural weakening and eventual fissuring and erosion of the cartilage.

- Enzyme Production: Dysfunctional chondrocytes and synovial cells produce excessive amounts of proteolytic enzymes:

- Cartilage Changes:

- Softening and Fibrillation: The cartilage surface becomes rough, soft, and frayed, developing cracks and fissures (fibrillation).

- Thinning and Erosion: These fissures deepen, and the cartilage gradually thins, eventually eroding completely in areas, exposing the underlying subchondral bone.

- Subchondral Bone Involvement:

- Increased Stress: Once the protective cartilage layer is compromised, the subchondral bone bears increased mechanical stress.

- Bone Sclerosis: The bone beneath the damaged cartilage responds by becoming denser and thicker (subchondral sclerosis).

- Cyst Formation: Small fluid-filled cavities (subchondral cysts) can form within the bone.

- Osteophyte Formation: At the joint margins, the body attempts to increase the surface area and stabilize the joint by forming new bone outgrowths called osteophytes (bone spurs). These contribute to joint stiffness and can impinge on surrounding tissues.

- Synovial Inflammation (Secondary Synovitis):

- Detritus Release: Cartilage and bone fragments (detritus) released into the synovial fluid act as irritants.

- Inflammatory Response: These irritants trigger a low-grade inflammatory response in the synovial membrane, causing the synovium to become inflamed (synovitis).

- Mediator Release: The inflamed synovium releases pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-1, TNF-alpha) and more degradative enzymes, further contributing to cartilage breakdown and pain. This secondary inflammation, while typically less severe than in RA, contributes to pain and effusions.

- Ligament and Meniscus Changes:

- Ligaments can become stretched and lax (leading to instability) or fibrotic and stiff.

- Menisci (in the knee) can degenerate, tear, and lose their shock-absorbing capacity.

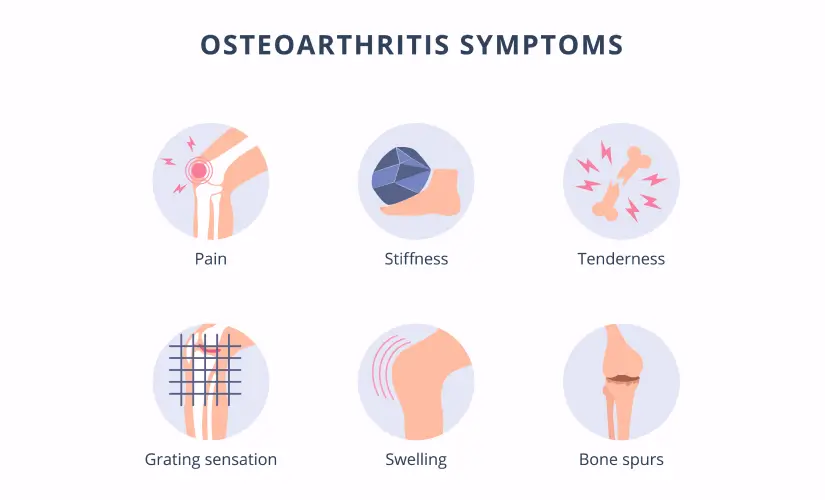

- Pain: Primarily arises from the inflamed synovium, stretching of the joint capsule, subchondral bone (which is innervated), muscle spasms, and pressure from osteophytes.

- Stiffness: Due to synovial inflammation, joint effusion, muscle guarding, and osteophyte formation.

- Loss of Function: Resulting from pain, stiffness, muscle weakness, and joint instability/deformity.

- Crepitus: The grinding sensation or sound caused by rough cartilage surfaces rubbing against each other.

- Deformity: Due to loss of cartilage, subchondral bone changes, and osteophyte formation, leading to altered joint alignment.

The clinical manifestations of Osteoarthritis (OA) are a direct result of the pathological changes within the joint, primarily cartilage degradation, subchondral bone remodeling, and secondary synovitis. The disease has a slow, insidious onset and a progressive course, gradually worsening over years.

- Joint Pain:

- Most prominent symptom.

- Characteristics:

- Deep, aching pain, often described as "gnawing" or "sore."

- Mechanical pattern: Typically worsens with activity, weight-bearing, and prolonged use.

- Relieved by rest in the early stages.

- May become more constant and present at rest or even at night as the disease progresses, especially due to secondary inflammation or subchondral bone pain.

- Aggravated by cold, damp weather in some individuals.

- Joint Stiffness:

- "Gelling phenomenon": Stiffness occurs after periods of inactivity or rest.

- Morning Stiffness: Classic presentation, but typically brief, lasting less than 30 minutes (a key differentiator from RA). It improves with movement.

- Stiffness can also occur after sitting for prolonged periods ("post-rest stiffness").

- Crepitus (Cracking, Grating, or Grinding Sensation):

- Often felt and sometimes heard during joint movement.

- Caused by the roughened articular surfaces of cartilage and bone rubbing against each other.

- Functional Limitation and Decreased Range of Motion (ROM):

- Due to pain, stiffness, joint effusions, and osteophyte formation.

- Can significantly impact activities of daily living (ADLs) and quality of life.

- Patients may avoid using the affected joint due to pain, leading to muscle weakness and atrophy around the joint.

- Joint Swelling / Effusion:

- May occur intermittently, especially after activity, due to inflammation of the synovial membrane (secondary synovitis) or accumulation of joint fluid.

- Often feels "hard" if due to bony enlargement, or "boggy" if due to synovial thickening/fluid.

- Typically less pronounced, less warm, and less symmetrical than in RA.

- Tenderness:

- Localized tenderness over the joint line or surrounding structures.

- Joint Deformity and Enlargement:

- Bony enlargement: Due to osteophyte formation and subchondral bone thickening.

- Heberden's Nodes: Bony enlargements at the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints of the fingers, particularly common in women, often genetic.

- Bouchard's Nodes: Bony enlargements at the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints of the fingers, less common than Heberden's nodes.

- Malalignment: Asymmetry and altered joint axis (e.g., genu varum/bow-legged in knee OA, valgus/knock-kneed in some cases).

- Muscle Weakness and Atrophy:

- Result from disuse due to pain and guarding, further contributing to joint instability.

OA typically affects certain joints more frequently and often in an asymmetrical pattern:

- Weight-Bearing Joints:

- Knees: Very common, leading to difficulty walking, climbing stairs, and standing.

- Hips: Can cause pain in the groin, buttock, or thigh; difficulty with ambulation, bending, and putting on shoes/socks.

- Spine: Cervical and lumbar spine (especially facet joints), leading to back pain, stiffness, and sometimes nerve compression (radiculopathy).

- Small Joints of the Hands:

- Distal Interphalangeal (DIP) joints: Leading to Heberden's nodes.

- Proximal Interphalangeal (PIP) joints: Leading to Bouchard's nodes.

- First Carpometacarpal (CMC) joint of the thumb: Causes pain at the base of the thumb, difficulty with grasping, pinching, and fine motor tasks.

- Feet:

- First Metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint: (big toe), leading to bunions and pain with walking.

- Midfoot.

- Less Commonly Affected: Wrists, elbows, shoulders, ankles (unless due to prior injury). These are more characteristic of inflammatory arthropathies or post-traumatic OA.

- Slow and Gradual: OA is typically a slowly progressive disease, with symptoms gradually worsening over many years.

- Intermittent Flare-ups: Patients may experience periods of increased pain and stiffness (flare-ups) often triggered by overuse, injury, or changes in weather.

- Variability: The rate of progression varies widely among individuals and even between different joints in the same person. Some may have mild symptoms for decades, while others experience rapid progression to severe joint damage and disability.

- Impact on Quality of Life: As the disease advances, pain becomes more constant, functional limitations increase, and quality of life can be significantly impacted, affecting work, leisure, and daily activities.

Diagnosing Osteoarthritis (OA) primarily relies on a combination of a thorough patient history, physical examination, and characteristic radiological findings. Unlike Rheumatoid Arthritis, there are no specific blood tests that definitively diagnose OA. Laboratory tests are more often used to rule out other forms of arthritis.

- Symptom Onset and Duration: Gradual onset, typically over months to years.

- Pain Characteristics: Location, Quality (aching, deep), Aggravating factors, Alleviating factors (rest), Timing (worse at end of day).

- Stiffness: Morning stiffness (brief, < 30 minutes), Stiffness after rest ("gelling phenomenon").

- Functional Limitations: Impact on daily activities (walking, climbing stairs, dressing, grasping).

- Past Medical History: Previous joint injuries, surgeries, other medical conditions (e.g., diabetes, gout).

- Family History: History of OA in close relatives.

- Risk Factors: Obesity, occupational activities, sports.

- Absence of Systemic Symptoms: Crucial for differentiating from inflammatory arthropathies (no fever, malaise, significant weight loss).

- Inspection:

- Joint enlargement: Bony (osteophytes, Heberden's/Bouchard's nodes) rather than soft tissue swelling.

- Deformity/Malalignment: Varus (bow-legged) or valgus (knock-kneed) deformities in knees, ulnar deviation in hands (less common than RA).

- Muscle atrophy: Especially quadriceps in knee OA.

- Palpation:

- Tenderness: Localized over joint line or surrounding structures.

- Warmth: May be present with effusions but usually less pronounced than in inflammatory arthritis.

- Effusion: Detectable fluid accumulation (e.g., patellar tap test in knees).

- Range of Motion (ROM):

- Decreased ROM: Active and passive ROM may be limited due to pain, stiffness, or osteophytes.

- Crepitus: Palpable or audible crepitation (grating/grinding) during joint movement.

- Stability: Assess joint stability; ligamentous laxity can be a consequence or contributing factor.

- Functional Assessment: Observe gait, ability to perform tasks (e.g., squat, get out of chair).

- X-rays (Radiographs):

- Gold standard for confirming diagnosis and assessing severity.

- Characteristic Findings:

- Joint Space Narrowing: Due to cartilage loss. This is often the earliest and most consistent finding.

- Osteophytes: Bone spurs at the joint margins.

- Subchondral Sclerosis: Increased density of bone beneath the cartilage.

- Subchondral Cysts: Fluid-filled cavities within the subchondral bone.

- Joint Malalignment: Changes in the normal axis of the joint.

- Kellgren-Lawrence Grading System: Commonly used to grade radiographic severity of OA (Grade 0: no OA, Grade 4: severe OA with large osteophytes, marked joint space narrowing, severe sclerosis).

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI):

- Not routinely used for initial diagnosis of OA due to cost and availability, as X-rays are usually sufficient.

- Useful for: Evaluating soft tissue structures (menisci, ligaments, tendons), Assessing early cartilage damage, Detecting bone marrow edema, Ruling out other conditions.

- Ultrasound:

- Can be used to detect synovial effusions, synovial inflammation, osteophytes, and subtle cartilage changes.

- Useful for guiding injections.

- No specific diagnostic blood tests for OA.

- Purpose: Primarily used to rule out other conditions, particularly inflammatory arthropathies like RA.

- Typical Findings in OA:

- Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) and C-Reactive Protein (CRP): Usually normal or only mildly elevated. Significant elevation would suggest an inflammatory arthritis.

- Rheumatoid Factor (RF) and Anti-Cyclic Citrullinated Peptide (anti-CCP) antibodies: Negative. Positive results would suggest RA.

- Synovial Fluid Analysis:

- If a joint effusion is aspirated, the fluid in OA is typically "non-inflammatory" (clear, viscous, low cell count < 2000 WBCs/mm3).

- Used to rule out other causes of effusion (e.g., infection, crystal-induced arthritis like gout or pseudogout).

While there are classification criteria (e.g., American College of Rheumatology criteria) often used for research, a clinical diagnosis of OA is typically made when:

- The patient presents with characteristic symptoms (e.g., pain, brief morning stiffness).

- Physical examination reveals typical signs (e.g., bony enlargement, crepitus, reduced ROM).

- X-rays show characteristic features (e.g., joint space narrowing, osteophytes).

- Other conditions (especially inflammatory arthritis) have been excluded.

- To relief pain

- To minimize progress of the condition

- To restore normal functions of the bones.

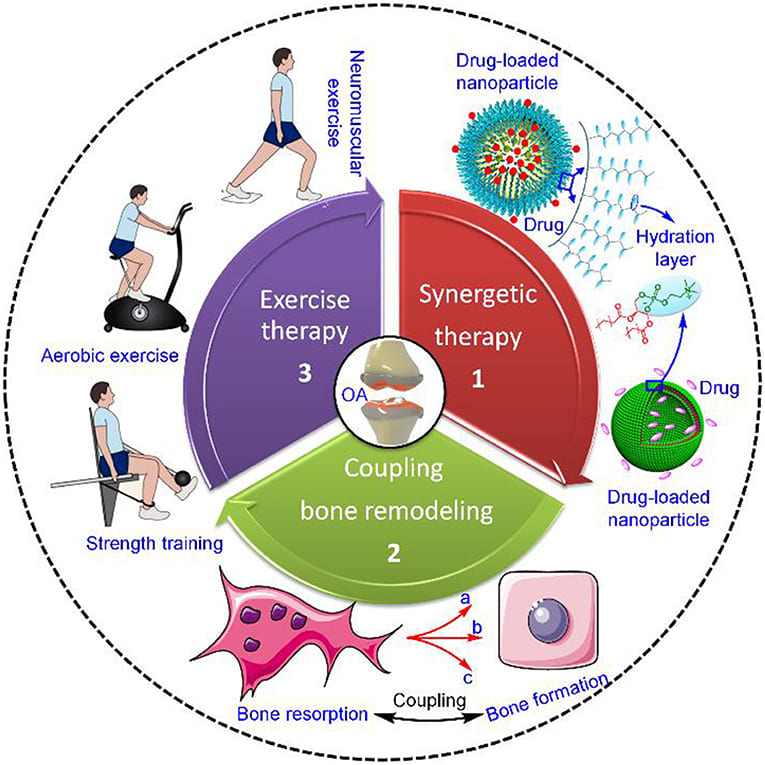

Pharmacological management for Osteoarthritis (OA) primarily focuses on pain relief and improvement of function, as there are currently no medications that can halt or reverse the cartilage degeneration that is the hallmark of OA. The approach is typically stepwise, starting with less potent and safer options and progressing to stronger medications if symptoms persist.

Often the first line for localized pain, especially in peripheral joints like knees and hands, due to fewer systemic side effects.

- Topical Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs):

- Mechanism: Reduce pain and inflammation directly at the site of application with minimal systemic absorption.

- Examples: Diclofenac gel/solution (Voltaren Gel, Pennsaid).

- Indications: Mild to moderate OA pain, especially knee and hand OA.

- Advantages: Lower risk of gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, and renal side effects compared to oral NSAIDs.

- Capsaicin Cream:

- Mechanism: Derived from chili peppers, it depletes substance P (a neurotransmitter involved in pain transmission) from nerve endings.

- Indications: Localized OA pain.

- Considerations: Requires regular application for several weeks to be effective. Can cause a burning sensation initially.

- Acetaminophen (Paracetamol):

- Mechanism: Analgesic (pain reliever) and antipyretic (fever reducer); its exact mechanism in pain relief is not fully understood but thought to involve central nervous system pathways.

- Indications: First-line oral agent for mild to moderate OA pain.

- Dosage: Up to 3-4 grams/day (depending on formulation and patient factors).

- Considerations: Generally safe but can cause liver damage with overdose or in patients with liver disease. Maximum dose should be strictly adhered to.

- Oral Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs):

- Mechanism: Inhibit cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes, reducing prostaglandin production, which mediates pain and inflammation.

- Examples: Ibuprofen, naproxen, celecoxib (a COX-2 selective inhibitor).

- Indications: Moderate to severe OA pain, especially if there's an inflammatory component (e.g., synovitis).

- Considerations:

- Side Effects: Significant risk of gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding/ulcers, cardiovascular events (e.g., heart attack, stroke), and renal impairment.

- COX-2 Selective NSAIDs (e.g., celecoxib): Lower GI risk but similar cardiovascular risk to non-selective NSAIDs.

- Use the lowest effective dose for the shortest duration.

- Often prescribed with a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) for GI protection in high-risk patients.

These involve injecting medication directly into the affected joint.

- Corticosteroid Injections (e.g., Triamcinolone, Methylprednisolone):

- Mechanism: Potent anti-inflammatory agents that reduce inflammation within the joint.

- Indications: Acute pain flares, especially when accompanied by inflammation or effusion.

- Efficacy: Provides short-term pain relief (weeks to a few months).

- Considerations:

- Should be limited to 3-4 injections per year per joint due to potential for cartilage damage with repeated injections, and infection risk.

- Requires sterile technique.

- Hyaluronic Acid Injections (Viscosupplementation):

- Mechanism: Hyaluronic acid is a natural component of synovial fluid and cartilage. Injections aim to restore the viscoelastic properties of synovial fluid, providing lubrication, shock absorption, and anti-inflammatory effects.

- Examples: Synvisc, Hyalgan, Euflexxa.

- Indications: Moderate knee OA, typically after oral analgesics and NSAIDs have failed. Less evidence for other joints.

- Efficacy: Provides modest and variable pain relief for a longer duration (up to 6 months) than corticosteroids. Onset of action may be delayed.

- Considerations: May require a series of injections. Generally well-tolerated with minimal systemic side effects, but local pain, swelling, or allergic reactions can occur.

- Mechanism: Act on opioid receptors in the brain and spinal cord to reduce pain perception.

- Examples: Tramadol (weak opioid), hydrocodone, oxycodone.

- Indications: Reserved for severe OA pain not responsive to other therapies, especially in patients who are not surgical candidates or while awaiting surgery.

- Considerations:

- High risk of side effects: Nausea, constipation, sedation, dizziness.

- Risk of dependence, addiction, and tolerance.

- Careful monitoring and judicious use are essential. Not recommended for long-term routine use in OA due to risks vs. benefits.

- Duloxetine (Cymbalta):

- Mechanism: Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) antidepressant, also approved for chronic musculoskeletal pain.

- Indications: When other treatments are insufficient, particularly if there's a neuropathic pain component or co-morbid depression/anxiety.

- Muscle Relaxants:

- Indications: Can be used for short periods to address muscle spasms contributing to OA pain.

- Considerations: May cause sedation.

- Glucosamine and Chondroitin Sulfate:

- Mechanism: Natural components of cartilage. Supplements are marketed to support joint health.

- Evidence: Mixed and often conflicting evidence regarding efficacy in reducing pain or slowing disease progression. Some studies show a modest benefit for pain relief in certain subgroups, while others show no benefit.

- Considerations: Not regulated as drugs by the FDA. Generally considered safe.

- Individualized Treatment: Tailored to the patient's specific symptoms, comorbidities, preferences, and risk factors.

- Stepwise Approach: Start with safer, less potent agents (e.g., topical NSAIDs, acetaminophen) and escalate if needed.

- Balance of Efficacy and Safety: Carefully weigh potential benefits against risks and side effects.

- Patient Education: Crucial for adherence, understanding realistic expectations, and recognizing side effects.

- Combination Therapy: Often involves using multiple agents with different mechanisms of action (e.g., topical NSAID + oral acetaminophen).

Non-pharmacological and rehabilitation strategies are considered the first-line and foundational treatments for Osteoarthritis (OA). They are for pain management, improving function, slowing disease progression, and enhancing the patient's overall quality of life. These interventions are often safe, cost-effective, and empower patients to actively participate in their own care.

- Weight Management:

- Rationale: Obesity is a significant risk factor, especially for knee and hip OA. Even modest weight loss (5-10% of body weight) can significantly reduce pain, improve function, and slow disease progression by reducing mechanical load on joints and decreasing systemic inflammation (adipokines).

- Intervention: Dietary changes, increased physical activity.

- Exercise and Physical Activity:

- Rationale: Crucial for maintaining joint health, strengthening supporting muscles, improving flexibility, and reducing pain. "Motion is lotion" for OA joints.

- Types:

- Low-impact Aerobic Exercise: Walking, cycling, swimming, aquarobics, elliptical training. Improves cardiovascular fitness without excessive joint stress.

- Strength Training: Strengthening muscles around the affected joint (e.g., quadriceps for knee OA, hip abductors for hip OA) improves joint stability and reduces load.

- Flexibility and Range of Motion (ROM) Exercises: Gentle stretching and ROM exercises prevent stiffness and maintain joint mobility.

- Balance Exercises: Important for fall prevention, especially in older adults with lower limb OA.

- Considerations: Exercise should be tailored to the individual's pain levels and joint involvement. Start slowly and gradually increase intensity and duration. Pain during exercise should be mild and resolve quickly after stopping.

- Joint Protection Techniques:

- Rationale: Teach patients how to perform daily activities in ways that minimize stress on affected joints.

- Examples: Using larger, stronger joints instead of smaller, weaker ones. Avoiding prolonged static positions. Distributing weight evenly. Using assistive devices.

- Role: A cornerstone of OA management, often prescribed by a physician. A physical therapist provides individualized assessment and treatment plans.

- Interventions:

- Therapeutic Exercise Programs: Tailored exercises to improve strength, flexibility, balance, and endurance.

- Manual Therapy: Joint mobilization, massage to reduce pain and improve range of motion.

- Modalities: Heat/cold therapy, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) for pain relief.

- Patient Education: Teaching about body mechanics, posture, pacing activities, and long-term self-management strategies.

- Role: Helps patients maintain independence and function in daily activities.

- Interventions:

- Activity Modification: Strategies for performing tasks (e.g., dressing, cooking, bathing) with less pain and effort.

- Adaptive Equipment: Recommending and training in the use of assistive devices (e.g., long-handled reachers, jar openers, elevated toilet seats, shower chairs).

- Home Modifications: Suggesting changes in the home environment to improve safety and accessibility.

- Assistive Devices:

- Rationale: Reduce load on affected joints, improve stability, and aid mobility.

- Examples: Canes, walkers, crutches. A cane used in the hand opposite the affected leg significantly reduces load on the hip/knee.

- Braces and Orthotics:

- Rationale: Provide support, stability, improve alignment, and redistribute weight.

- Examples:

- Knee Braces (Unloader braces): Designed to shift weight from the damaged compartment of the knee (e.g., medial compartment) to the healthier side.

- Foot Orthotics/Insoles: Can alter foot mechanics and reduce stress on knee or hip joints.

- Splints: For hand/wrist OA to provide rest and support.

- Heat Therapy (Moist heat packs, warm baths/showers):

- Rationale: Increases blood flow, relaxes muscles, reduces stiffness, and provides comfort.

- Indications: For chronic pain and stiffness.

- Cold Therapy (Ice packs):

- Rationale: Reduces inflammation, swelling, and numbs the area, providing pain relief.

- Indications: For acute pain flares, post-activity soreness, or joint effusion.

- Rationale: Empower patients to understand their condition, manage symptoms, and make informed decisions about their health.

- Content: Disease process, treatment options, pain coping strategies, importance of exercise and weight management, goal setting.

- Programs: Chronic disease self-management programs, OA-specific education classes.

- Rationale: A traditional Chinese medicine technique involving the insertion of thin needles into specific points on the body. Believed to modulate pain pathways.

- Evidence: Some studies suggest it can provide short-term pain relief and improve function in knee OA, though findings are mixed.

- Rationale: Delivers low-voltage electrical current through electrodes placed on the skin, thought to block pain signals or stimulate endorphin release.

- Evidence: May provide short-term pain relief for some individuals with OA.

- Rationale: Chronic pain can lead to depression, anxiety, and sleep disturbances. Addressing these psychosocial factors is important for overall well-being and pain coping.

- Interventions: Counseling, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), support groups, stress reduction techniques.

The primary goals of OA surgery are to alleviate pain, restore joint function, improve quality of life, and correct deformities. The choice of surgical procedure depends on several factors: the specific joint involved, the patient's age, activity level, overall health, and the extent of joint damage.

A minimally invasive procedure where a small incision is made, and an arthroscope (a thin tube with a camera) is inserted into the joint. Small instruments are then used to perform various procedures.

- Procedures Performed: Debridement (Removal of loose bodies or trimming of frayed cartilage), Lavage (Washing out inflammatory mediators), Meniscectomy (Removal of damaged meniscal tissue).

- Indications: Primarily for early OA or to address specific mechanical symptoms (e.g., locking, catching) caused by loose bodies or meniscal tears.

- Efficacy: Limited role in treating generalized OA. Benefits for pain relief in OA are often short-lived or not superior to conservative treatment in many cases. Often considered when specific mechanical issues are present.

A surgical procedure that involves cutting and reshaping a bone (usually in the knee or hip) to realign the joint and shift weight-bearing forces from a damaged area to a healthier part of the joint.

- Types (e.g., for knee OA): High Tibial Osteotomy (HTO) for medial compartment knee OA (bow-legged deformity). Distal Femoral Osteotomy for lateral compartment knee OA (knock-kneed deformity).

- Indications: Typically for younger, active patients with OA affecting only one side (compartment) of the joint, where joint replacement is not yet suitable. It aims to delay the need for total joint replacement.

- Efficacy: Can provide significant pain relief and improved function for several years, preserving the patient's own joint.

A surgical procedure that permanently fuses the bones of a joint together, eliminating movement in that joint.

- Indications: Reserved for severe, debilitating OA in joints where motion is less critical or where other options (like joint replacement) are not feasible (e.g., due to infection, significant bone loss, or failed previous surgeries). Common in the spine (spinal fusion), foot/ankle, or wrist.

- Efficacy: Provides excellent pain relief by eliminating motion in the affected joint, but at the cost of complete loss of mobility.

This is the most common and often most effective surgical treatment for advanced OA, particularly in the hip and knee.

- Total Joint Arthroplasty (TJA) / Total Joint Replacement (TJR): The entire damaged joint surfaces are removed and replaced with artificial components (prostheses) made of metal, plastic, or ceramic.

- Common Joints: Total Hip Replacement (THR), Total Knee Replacement (TKR). Shoulder, ankle, and finger joint replacements are also performed.

- Indications: Severe, end-stage OA with persistent pain, significant functional limitation, and radiographic evidence of extensive damage, unresponsive to conservative management.

- Efficacy: Highly successful in relieving pain and restoring function in the vast majority of patients. Considered one of the most successful surgical procedures.

- Considerations: Lifespan of Prosthesis (Typically 15-20+ years), Rehabilitation (Critical for optimal outcomes), Risks (Infection, blood clots, nerve damage, dislocation, periprosthetic fracture).

- Partial Joint Arthroplasty (e.g., Unicompartmental Knee Arthroplasty - UKA): Only the damaged compartment of a joint (e.g., medial compartment of the knee) is replaced, preserving the healthy compartments and ligaments.

- Indications: Younger, active patients with OA limited to a single compartment of the knee, with intact ligaments and good alignment in the other compartments.

- Efficacy: Can offer good pain relief, quicker recovery, and more natural knee kinematics compared to TKR for suitable candidates.

- Considerations: Not suitable if OA is present in multiple compartments. May require conversion to TKR later if OA progresses in other compartments.

A group of procedures aimed at repairing or regenerating damaged articular cartilage.

- Types:

- Microfracture: Creating small holes in the subchondral bone to stimulate the formation of fibrocartilage.

- Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation (ACI): Healthy cartilage cells are harvested, grown in a lab, and implanted.

- Osteochondral Autograft/Allograft Transplantation (OATS/OCA): Transferring healthy cartilage and bone plugs from a less weight-bearing area or cadaver.

- Indications: Generally for younger patients with localized, focal cartilage defects (often due to trauma), rather than widespread OA. Not typically used for diffuse, end-stage OA.

- Efficacy: Variable results, often aiming to delay the progression of OA rather than cure it.

- Pre-operative Education: Preparing patients for surgery, managing expectations, understanding recovery, pain management, and preventing complications.

- Post-operative Monitoring: Assessing for complications (infection, DVT/PE, nerve injury), managing pain, facilitating early mobilization, and assisting with rehabilitation exercises.

- Discharge Planning: Ensuring patients have the necessary support, equipment, and understanding of their ongoing rehabilitation plan.

- Chronic Pain related to joint inflammation, cartilage degeneration, muscle spasm, and altered joint function.

- Impaired Physical Mobility related to pain, stiffness, decreased range of motion, muscle weakness, and joint instability.

- Activity Intolerance related to pain on exertion, muscle weakness, and fatigue.

- Inadequate health Knowledge regarding the disease process, treatment regimen, and self-management strategies.

- Excessive Anxiety/Fear related to chronic pain, potential for increasing disability, and uncertain prognosis.

- Disrupted Body Image related to joint deformities, functional limitations, and perceived loss of independence.

- Ineffective Coping related to chronic pain, disability, and role changes.

- Risk for Falls related to impaired balance, muscle weakness, gait changes, and use of assistive devices.

- Self-Care Deficit (e.g., Feeding, Bathing, Dressing) related to pain, stiffness, and decreased dexterity or mobility.

Goal: Patient reports pain is managed to an acceptable level and utilizes non-pharmacological pain relief strategies effectively.

| Interventions | Details |

|---|---|

| Assess Pain | Regularly assess pain characteristics (location, intensity, quality, duration, aggravating/alleviating factors) using a pain scale (e.g., 0-10). |

| Administer Analgesics | Administer prescribed pharmacological agents (e.g., acetaminophen, NSAIDs, topical analgesics, opioids) and monitor for effectiveness and side effects. |

| Apply Non-Pharmacological Strategies |

|

| Education | Educate patient on medication side effects, appropriate dosing, and the importance of using non-pharmacological methods. |

| Activity Pacing | Teach patient to balance rest and activity to prevent exacerbation of pain. |

| Splinting/Bracing | Apply or assist with application of prescribed splints or braces to support painful joints. |

Goal: Patient maintains optimal physical mobility within limitations and demonstrates adaptive techniques for safe movement.

| Interventions | Details |

|---|---|

| Assess Mobility | Evaluate current level of mobility, range of motion, gait, muscle strength, and presence of assistive devices. |

| Encourage Exercise |

|

| Assistive Devices |

|

| Positioning | Encourage proper body alignment and positioning to prevent contractures and discomfort. |

| Rest Periods | Plan for rest periods between activities to prevent fatigue and joint stress. |

Goal: Patient participates in desired activities with minimal discomfort and manages energy effectively.

| Interventions | Details |

|---|---|

| Assess Baseline | Determine patient's current activity level and factors that worsen intolerance. |

| Monitor Vitals | Monitor vital signs before, during, and after activity. |

| Pacing Activities | Instruct patient on pacing activities, breaking tasks into smaller components, and taking frequent rest breaks. |

| Prioritization | Help patient prioritize activities to conserve energy for essential tasks. |

| Energy Conservation Techniques | Teach techniques like sitting for tasks, using assistive devices, and avoiding prolonged standing. |

| Progressive Exercise | Collaborate with PT to gradually increase activity levels and exercise tolerance. |

Goal: Patient verbalizes understanding of OA, its management, and self-care strategies.

| Interventions | Details |

|---|---|

| Assess Learning Needs | Determine patient's current knowledge, readiness to learn, and preferred learning style. |

| Provide Information |

|

| Resources | Provide written materials, reputable websites, and information about support groups. |

| Demonstration/Return Demonstration | Demonstrate correct use of assistive devices or exercise techniques and ask for return demonstration. |

| Open Communication | Encourage questions and provide opportunities for discussion. |

Goal: Patient expresses reduced anxiety/fear and utilizes effective coping mechanisms.

| Interventions | Details |

|---|---|

| Active Listening | Listen attentively to patient's concerns and fears about pain, disability, and the future. |

| Provide Reassurance | Reassure patient that symptoms can be managed and support is available. |

| Education | Provide accurate information about the condition and treatment options to reduce fear of the unknown. |

| Coping Strategies | Teach relaxation techniques, deep breathing exercises, and guided imagery. |

| Referrals | Consider referral to support groups, counseling, or social work if anxiety is significant or prolonged. |

| Empowerment | Encourage patient participation in decision-making regarding their care. |

Goal: Patient remains free from falls.

| Interventions | Details |

|---|---|

| Assess Fall Risk | Conduct a thorough fall risk assessment (e.g., using a validated tool). |

| Environment Modification |

|

| Footwear | Advise patient to wear sturdy, supportive, non-skid footwear. |

| Assistive Devices | Ensure proper use of canes/walkers and verify they are in good working condition. |

| Strength/Balance Training | Collaborate with PT for exercises to improve lower extremity strength, balance, and gait. |

| Medication Review | Review medications for those that may increase fall risk (e.g., sedatives, certain antihypertensives). |

Goal: Patient performs self-care activities to their maximum ability, using adaptive strategies as needed.

| Interventions | Details |

|---|---|

| Assess Deficit | Identify specific areas of self-care where the patient needs assistance. |

| Adaptive Equipment | Collaborate with occupational therapy (OT) to recommend and train the patient in the use of adaptive equipment (e.g., long-handled bath sponge, dressing aids, specialized utensils). |

| Pacing and Prioritization | Teach energy conservation techniques and help patient prioritize self-care tasks. |

| Modify Environment | Suggest modifications in the home to facilitate self-care (e.g., shower chair, comfortable seating). |

| Encourage Independence | Encourage patient to perform as much self-care as possible, providing assistance only when necessary. |

- Holistic Approach: Address not only the physical symptoms but also the psychological, social, and functional impacts of the disease.

- Patient-Centered Care: Tailor interventions to the individual patient's needs, preferences, and goals.

- Interdisciplinary Collaboration: Work closely with physicians, physical therapists, occupational therapists, social workers, and dietitians.

- Empowerment: Educate and empower patients to actively participate in their self-management and decision-making.

Prevention

- Weight reduction. To avoid too much weight upon the joints, reduction of weight is recommended.

- Prevention of injuries. As one of the risk factors for osteoarthritis is previous joint damage, it is best to avoid any injury that might befall the weight-bearing joints.

- Perinatal screening for congenital hip disease. Congenital and developmental disorders of the hip are well known for predisposing a person to OA of the hip.

- Keeping a healthy body weight

- Reduce on sugar intake.

Complications

- Bone death

- Bleeding inside the joint

- Rapid complete break down of cartilage

- Infection of the joint

- Rupture of tendons and

Some questions

good notes