Table of Contents

TogglePEPTIC ULCER DISEASE (PUD)

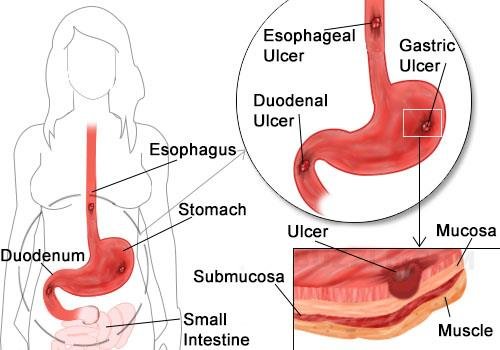

A peptic ulcer is defined as an excavation (a hollowed-out area) or an erosion that forms in the mucosal wall of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. This lesion occurs specifically in areas that are exposed to the corrosive actions of gastric acid and the digestive enzyme pepsin. These susceptible areas typically include the stomach, the pylorus (the opening from the stomach into the duodenum), the duodenum (the first part of the small intestine), or, less commonly, the esophagus.

The naming convention for a peptic ulcer directly reflects its anatomical location: it is referred to as a gastric ulcer when located in the stomach, a duodenal ulcer when found in the duodenum, or an esophageal ulcer if it occurs in the esophagus.

Classification of Peptic Ulcers: Acute vs. Chronic

Peptic ulcers are broadly classified based on their duration and the depth of tissue involvement, primarily into acute and chronic forms. This distinction is crucial for understanding their pathology, clinical course, and treatment approaches.

Acute Peptic Ulcers

- Characteristics: Acute peptic ulcers are typically associated with superficial erosion of the gastric or duodenal mucosa. This means the damage is primarily limited to the top layers of the lining, with minimal associated inflammation.

- Duration and Resolution: They are generally of short duration, often developing rapidly. A key feature of acute ulcers is their tendency to resolve quickly and completely once the underlying precipitating cause or irritant is identified and effectively removed or treated. For example, an ulcer caused by a single, high dose of NSAID might be acute.

- Nature of Lesion: The term "erosion" often describes an acute lesion that does not penetrate the muscularis mucosae (a thin layer of muscle in the mucosa), whereas a true ulcer penetrates this layer. Acute ulcers can still penetrate, but they are characterized by their rapid development and potential for quick healing.

Chronic Peptic Ulcers

- Characteristics: Chronic peptic ulcers are characterized by their long duration and the significant depth of tissue damage. Unlike acute ulcers, they erode deeply, penetrating through the muscular wall of the GI tract. This deep erosion often leads to the formation of fibrous scar tissue during the healing process, which can sometimes result in strictures or deformities.

- Clinical Course: These ulcers can persist continuously for many months, or they may manifest intermittently throughout a person's life, with periods of exacerbation and remission.

- Prevalence: Epidemiologically, chronic ulcers are considerably more common than acute erosions. They are estimated to be at least four times more prevalent, highlighting their significant impact on public health and the chronicity of the disease for many individuals. The most common cause of chronic peptic ulcers is persistent infection with Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori), or the long-term, continuous use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

- Risk of Complications: Due to their depth and chronicity, chronic ulcers carry a higher risk of serious complications, including hemorrhage, perforation, and obstruction.

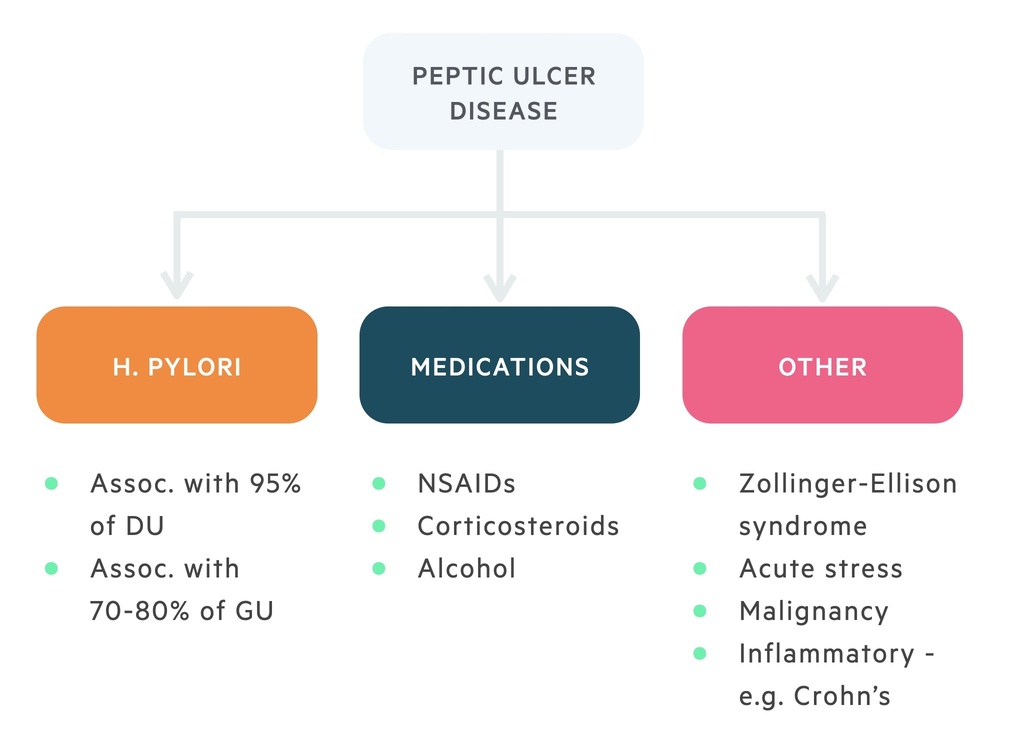

Etiology and Risk Factors

The development of Peptic Ulcer Disease (PUD) fundamentally arises from a critical imbalance within the gastrointestinal (GI) mucosa. This imbalance occurs between factors that aggressively attack the mucosal lining and those that provide protection. The primary aggressive factors are gastric acid and pepsin, while the key protective factors include the mucosal barrier (comprising mucus and bicarbonate production), adequate blood flow to the mucosa, and prostaglandins.

Causes and Predisposing Factors of PUD

Understanding these factors is crucial for prevention and effective management.

- Excessive Smoking: Smoking is a well-established risk factor. Nicotine and other chemicals in tobacco are thought to:

- Increase gastric acid secretion.

- Reduce the production of bicarbonate, which neutralizes acid.

- Decrease prostaglandin synthesis.

- Reduce gastric mucosal blood flow, impairing healing.

- Accelerate gastric emptying, exposing the duodenum to more acid.

- Excessive Alcohol Intake: Alcohol is a direct irritant to the gastric mucosa. High concentrations can cause superficial erosions and acute inflammation. Chronic heavy alcohol consumption can also impair mucosal healing and potentially contribute to the development of chronic gastritis and ulcers.

- Dietary Habits: While specific foods do not cause ulcers, certain items can irritate an existing ulcer or trigger symptoms. This includes highly spicy foods, very acidic foods (e.g., citrus fruits, tomatoes), and excessive caffeine intake, which can stimulate acid secretion.

- Severe Physiological Stress: Extreme physical stress, such as that experienced during major trauma, extensive burns, severe sepsis, multiple organ failure, or significant central nervous system injury, can lead to the formation of stress ulcers (also known as Curling's ulcers in burns or Cushing's ulcers in CNS trauma). These ulcers are typically acute, superficial, and often multiple. The mechanism involves reduced mucosal blood flow (ischemia) due to sympathetic nervous system activation, increased acid secretion, and impaired mucosal defenses.

- Psychological Stress: The role of psychological stress (e.g., emotional stress, anxiety) in causing PUD is less clear and remains a subject of ongoing research. While it is generally accepted that psychological stress does not directly cause ulcers, it may exacerbate symptoms in individuals with existing ulcers and potentially impair healing by affecting gastric motility, blood flow, and acid secretion.

- Family History: Individuals with a family history of peptic ulcers have an increased risk, suggesting a genetic component or shared environmental factors (e.g., H. pylori transmission within families).

- Blood Group Association: Blood group O is more commonly associated with duodenal ulcers, while blood group A has a slight association with gastric ulcers. The exact mechanism behind these associations is not fully understood but may involve differences in susceptibility to H. pylori colonization or mucosal integrity.

- Zollinger-Ellison Syndrome (ZES): A rare condition characterized by a gastrin-producing tumor (gastrinoma), usually in the pancreas or duodenum. This leads to extremely high levels of gastrin, which in turn causes massive hypersecretion of gastric acid, leading to severe, multiple, and often intractable ulcers in unusual locations.

- Other Medications: Certain medications, beyond NSAIDs, can also contribute, though less commonly. These include corticosteroids (when used in combination with NSAIDs), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), and some chemotherapy agents.

- Chronic Medical Conditions: Conditions like Crohn's disease, chronic kidney disease, cirrhosis, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) have been associated with an increased risk of PUD.

Types and Clinical Features of Peptic Ulcers: Gastric vs. Duodenal

While both gastric and duodenal ulcers are types of peptic ulcers, they exhibit distinct characteristics in terms of prevalence, demographics, physiological mechanisms, and symptom patterns. Understanding these differences is crucial for accurate diagnosis and tailored treatment.

| Characteristic | Gastric Ulcers (GUs) | Duodenal Ulcers (DUs) |

|---|---|---|

| Prevalence | Account for approximately 15-20% of all peptic ulcer cases. Less common than duodenal ulcers. | Account for the vast majority, approximately 80-85%, of all peptic ulcer cases. They are the most common type. |

| Age of Onset | Typically occur in an older age group, usually 50 years and older, with peak incidence between 55-65 years. | Tend to appear earlier in life, usually between 30-60 years of age, with peak incidence in the 40s. |

| Gender Ratio | More common in males and females equally (1:1), though some studies suggest a slight female predominance in older age. | Significantly more common in males than females (2-3:1), although the gap is narrowing. |

| Blood Group Association | More frequently observed in patients with blood group A. | Strongly associated with patients of blood group O. |

| H. pylori Association | Associated with H. pylori infection in about 70-80% of cases. NSAID use is also a significant cause. | Highly associated with H. pylori infection in about 90-95% of cases, making it the predominant cause. |

| Stomach Acid Secretion | Often associated with normal or even hypo-secretion (low) of stomach acid (HCl). The primary defect is often a compromised mucosal barrier rather than excessive acid. | Characteristically associated with hyper-secretion (high) of stomach acid (HCl), and often a faster rate of gastric emptying, exposing the duodenum to more acid. |

| Pain Pattern | Pain typically occurs relatively soon after meals, usually 30 minutes to 1 hour. Food ingestion may actually worsen the pain, leading to fear of eating and subsequent weight loss. | Pain characteristically occurs 2-3 hours after meals. It is often described as a burning or gnawing pain. A hallmark feature is that the pain is often relieved by eating food or taking antacids, as food buffers the acid. Pain frequently awakens the patient at night (between 1-2 AM) when acid secretion is high and food is absent. |

| Vomiting | Common, particularly after meals, and may provide temporary relief from pain. Associated with delayed gastric emptying. | Uncommon, unless complications like obstruction develop. |

| Weight Change | Often associated with weight loss, as patients tend to avoid eating due to post-prandial pain and nausea. | Often associated with weight gain, as patients learn that eating provides temporary relief from pain. |

| Hemorrhage Risk | More likely to cause hemorrhage, particularly from the lesser curvature of the stomach. Hematemesis (vomiting blood, which may look like fresh blood or "coffee grounds") is more common than melena (black, tarry stools). | While still a serious risk, they are less likely to cause major hemorrhage than gastric ulcers. If bleeding occurs, melena (black, tarry stools due to digested blood) is more common than hematemesis. |

| Malignancy Risk | Approximately 1-5% of gastric ulcers can be malignant (gastric cancer), making biopsy of all gastric ulcers mandatory to rule out malignancy. | Rarely associated with malignancies. Duodenal ulcers are almost always benign. |

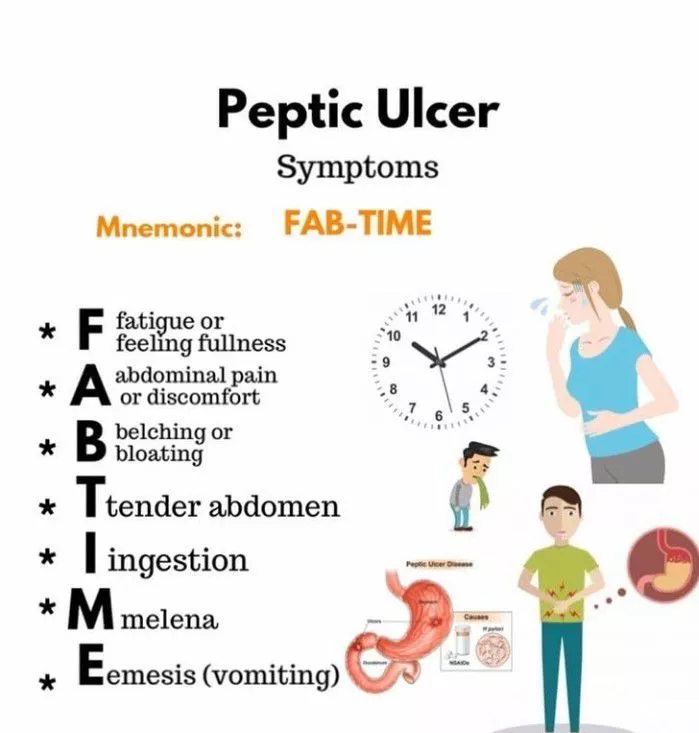

Clinical Manifestations of Uncomplicated Peptic Ulcer Disease (PUD)

The clinical presentation of PUD can vary, but certain symptoms are characteristic. It's important to note that some individuals, particularly the elderly or those on NSAIDs, may have "silent" ulcers without typical symptoms until a complication arises.

- The timing of pain in relation to meals is a key differentiator between gastric and duodenal ulcers (as detailed in the table above).

- Heartburn: A burning sensation in the chest, often rising from the epigastrium, similar to gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

- Dyspepsia: A constellation of upper abdominal symptoms, including bloating, fullness, early satiety, and indigestion.

Investigations for PUD

- Endoscopy (Esophagogastroduodenoscopy - EGD): The preferred diagnostic tool to directly visualize the ulcer, determine its size and location, and take biopsy samples.

- Gastric Biopsy: To test for H. pylori (rapid urease test) and to rule out gastric malignancy, especially for gastric ulcers.

- Tests for H. pylori: Urea breath test, stool antigen test, or serology (blood test for antibodies).

- Barium Swallow (Upper GI Series): An X-ray study that can reveal ulcers, but is less sensitive than endoscopy.

- Complete Blood Count (CBC): To assess for anemia due to chronic blood loss.

- Stool Analysis: For occult blood.

- Abdominal CT Scan: Used to diagnose complications like perforation or penetration.

Management of Peptic Ulcer Disease (PUD)

The comprehensive management of peptic ulcer disease is directed at several key objectives: alleviating pain, promoting the healing of the ulcer, preventing its recurrence, and diligently reducing the risk of serious complications. A patient-centered strategy, including thorough education and robust support, is paramount for achieving successful long-term outcomes.

Conservative / Non-Pharmacological Management: Foundations of Care

These interventions form the bedrock of PUD management, addressing both the underlying causes and factors that can exacerbate symptoms or impede healing.

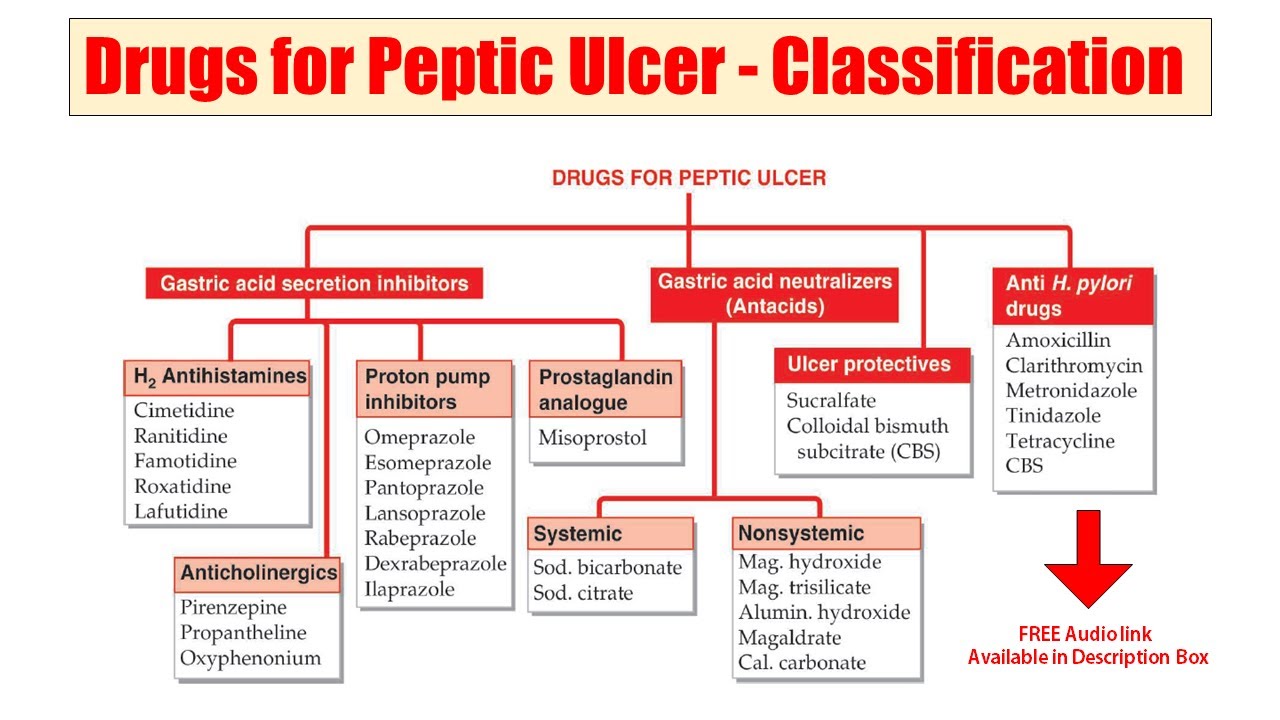

- "Triple Therapy": The standard approach involves a combination of two antibiotics and a proton pump inhibitor (PPI). Common antibiotic choices include amoxicillin, clarithromycin, and metronidazole. The PPI is crucial for reducing stomach acid, creating an environment conducive to antibiotic efficacy and ulcer healing. This regimen is typically administered for 10-14 days.

- "Quadruple Therapy": In cases of resistance to standard triple therapy, or in areas with high clarithromycin resistance, a quadruple therapy regimen may be employed. This usually includes a PPI, bismuth subsalicylate, and two antibiotics (e.g., metronidazole and tetracycline).

- Adherence is critical: Patients must complete the full course of antibiotics to ensure successful eradication and prevent antibiotic resistance.

- Cessation of Smoking: Smoking is a significant impediment to ulcer healing. It reduces gastric blood flow, impairs the production of protective prostaglandins, and increases acid secretion. Patients should be strongly encouraged to quit smoking entirely.

- Avoidance of Alcohol Consumption: Alcohol directly irritates the gastrointestinal (GI) mucosa and can stimulate acid secretion. Patients should be advised to abstain from alcohol or consume it only in very limited quantities.

- Dietary Changes: While there's no specific "ulcer diet," patients should identify and avoid foods and beverages that cause distress. Common culprits include highly spicy foods, acidic foods (e.g., citrus, tomatoes), caffeine (coffee, tea, colas), and carbonated drinks.

- Eating smaller, more frequent meals (e.g., 5-6 small meals a day) can help neutralize acid and reduce the gastric load, potentially minimizing pain and promoting healing.

- Avoid eating large meals just before bedtime.

- Stress Reduction and Rest: While stress doesn't directly cause ulcers, it can exacerbate symptoms and may impair the healing process by influencing gastric motility and acid secretion. Encouraging adequate rest, sleep, and implementing stress management techniques (e.g., meditation, yoga, deep breathing exercises) can be beneficial.

- Reduction or Avoidance of Chronic NSAID Use: Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) are a major cause of peptic ulcers. If possible, patients should discontinue NSAID use.

- Alternative Pain Relief: For pain management, alternatives like acetaminophen (paracetamol) should be considered.

- Gastroprotective Co-prescription: If NSAIDs are absolutely necessary (e.g., for chronic inflammatory conditions), they should be co-prescribed with a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) to provide gastroprotection.

- Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs): (e.g., omeprazole, lansoprazole, pantoprazole, esomeprazole, rabeprazole) are the most powerful acid suppressants. They work by irreversibly blocking the proton pump in gastric parietal cells, thereby reducing acid production significantly. PPIs are essential for ulcer healing and preventing recurrence, typically prescribed for 4-8 weeks to allow complete healing.

- H2-Receptor Antagonists (H2RAs): (e.g., famotidine, ranitidine - if available) reduce acid secretion by blocking histamine's action on gastric cells. Less potent than PPIs, but still effective for milder cases or as maintenance therapy.

- Antacids: (e.g., aluminum hydroxide, magnesium hydroxide, calcium carbonate) provide immediate, temporary relief of ulcer pain by neutralizing existing stomach acid. They are useful for symptomatic relief but do not promote healing as effectively as PPIs or H2RAs.

- Mucosal Protective Agents: (e.g., sucralfate, bismuth subsalicylate) act locally to form a protective barrier over the ulcer crater, shielding it from acid and pepsin. Sucralfate does not affect acid secretion. Bismuth also has some antibacterial properties against H. pylori.

Surgical Management: When Conservative Therapy Falls Short

Surgery for peptic ulcer disease is largely reserved for patients who experience complications unresponsive to intensive medical therapy or who present with acute, life-threatening events. Advances in pharmacological treatment, particularly the advent of PPIs and H. pylori eradication, have drastically reduced the need for surgical intervention.

- Intractable Ulcers: Ulcers that are chronic, recurrent, and fail to heal despite adequate and prolonged medical treatment.

- Hemorrhage (Bleeding): Acute, severe GI bleeding that cannot be controlled endoscopically, or recurrent bleeding despite multiple endoscopic attempts. Surgical intervention (e.g., oversewing the ulcer to ligate the bleeding vessel) may be necessary.

- Perforation: A medical emergency where the ulcer erodes completely through the stomach or duodenal wall, leading to spillage of GI contents into the peritoneal cavity, causing peritonitis. Requires immediate surgical repair.

- Obstruction (Gastric Outlet Obstruction): Chronic ulceration and inflammation, particularly in the pyloric region, can lead to scarring and narrowing (stenosis) that obstructs the passage of food from the stomach to the small intestine. Surgical procedures like pyloroplasty or vagotomy with gastrojejunostomy may be performed to relieve the obstruction.

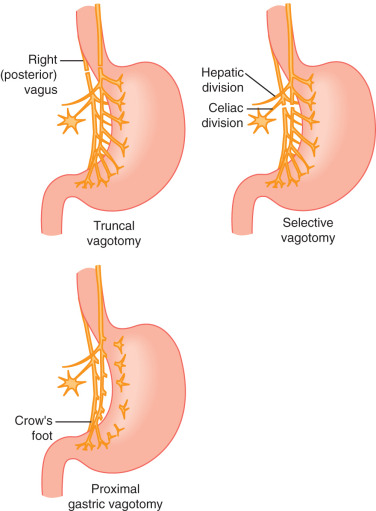

- Vagotomy: Severing the vagus nerve to reduce acid secretion. Can be truncal (cutting the main trunk) or selective/highly selective (cutting only branches supplying the stomach).

- Pyloroplasty: Widening the pylorus (the opening from the stomach to the duodenum) to improve gastric emptying, often performed with vagotomy.

- Antrectomy: Removal of the antrum (the lower part of the stomach) where gastrin is produced, often with vagotomy.

- Gastrectomy: Partial or total removal of the stomach. Reserved for very severe cases or malignancy.

Nursing Management for Peptic Ulcer Disease

Nursing care for patients with PUD is comprehensive, focusing on symptom management, patient education, emotional support, and vigilant monitoring for complications. A holistic approach is essential for optimal patient outcomes.

1. Acute Pain

- Routinely assess and document pain characteristics: location (epigastric, radiating to back), intensity (using a 0-10 scale), quality (burning, gnawing, aching), onset, duration, and precipitating/alleviating factors (e.g., food intake, medications).

- Observe for non-verbal cues of pain (restlessness, guarding, facial grimacing).

- Note if pain is relieved by food (duodenal ulcer) or exacerbated by food (gastric ulcer).

- Administer prescribed medications (PPIs, H2RAs, antacids) as ordered. Educate on proper timing (e.g., PPIs 30-60 min before meals, antacids 1-3 hours after meals and at bedtime).

- Encourage small, frequent, bland meals.

- Advise avoidance of known irritants (spicy foods, caffeine, alcohol, NSAIDs).

- Teach and encourage non-pharmacological pain relief methods:

- Relaxation techniques (deep breathing, guided imagery, meditation).

- Application of warmth to the abdomen (e.g., warm compress or heating pad).

- Distraction techniques.

- Provide a quiet and comfortable environment to promote rest and reduce stress.

- Monitor effectiveness of pain interventions and adjust as needed.

2. Risk for Bleeding (Hemorrhage)

- Monitor vital signs frequently for signs of hypovolemia: tachycardia, hypotension, weak thready pulse, tachypnea.

- Assess for signs of occult or overt GI bleeding:

- Hematemesis: Bright red (fresh blood) or "coffee-ground" vomitus. Note amount, color, and frequency.

- Melena: Black, tarry, foul-smelling stools (digested blood). Assess stool color, consistency, and frequency.

- Hematochezia: Bright red blood in stool (lower GI bleed or rapid upper GI bleed).

- Monitor H&H (hemoglobin and hematocrit) levels, and coagulation studies (PT/INR, PTT).

- Assess for signs of shock: pallor, diaphoresis, cold clammy skin, decreased urine output, altered mental status.

- Perform frequent guaiac testing of stools and gastric aspirate if nasogastric tube is in place.

- Maintain NPO status if active bleeding is suspected or confirmed.

- Establish large-bore IV access for fluid resuscitation. Administer IV fluids (crystalloids, colloids) and blood products as prescribed.

- Administer IV PPIs or H2RAs as ordered to reduce acid and promote clot stability.

- Prepare for and assist with endoscopic procedures (e.g., sclerotherapy, epinephrine injection, clipping) to control bleeding.

- Insert and manage a nasogastric (NG) tube if ordered, for gastric lavage or aspiration.

- Monitor urine output carefully as an indicator of renal perfusion.

- Educate the patient and family on signs of bleeding and the importance of immediate reporting.

3. Inadequate protein energy intake

- Monitor weight, noting any significant losses.

- Assess dietary intake and eating patterns; identify food intolerances or triggers.

- Observe for signs of nutrient deficiencies (e.g., fatigue, poor wound healing).

- Assess for nausea, vomiting, or early satiety.

- Encourage small, frequent, bland meals that are easily digestible.

- Educate the patient on dietary modifications, emphasizing foods to avoid (irritants) and foods to include (nutritious, non-acidic, non-spicy options).

- Administer antiemetics as prescribed to control nausea/vomiting.

- Provide good oral hygiene before and after meals to enhance appetite.

- Monitor fluid and electrolyte balance, especially if vomiting is present.

- Consider nutritional supplements or collaboration with a dietitian for comprehensive nutritional planning if oral intake remains inadequate.

- Advise avoiding eating immediately before bedtime to reduce reflux.

4. Deficient Knowledge

- Assess the patient's current understanding of PUD, its causes, treatment, potential complications, and self-care strategies.

- Identify the patient's preferred learning style and readiness to learn.

- Evaluate barriers to learning or adherence (e.g., health literacy, cognitive impairment).

- Provide clear, concise, and accurate information about PUD, including:

- The nature of the disease and its common causes (especially H. pylori and NSAIDs).

- Purpose, dosage, potential side effects, and proper timing of all prescribed medications (PPIs, H2RAs, antacids, antibiotics for H. pylori). Emphasize the importance of completing antibiotic courses.

- Detailed dietary modifications (foods to avoid, recommended eating patterns).

- Importance of lifestyle changes (smoking cessation, alcohol avoidance, stress management techniques).

- Recognition of signs and symptoms of complications requiring immediate medical attention (e.g., persistent severe abdominal pain, sudden sharp pain, black tarry stools, coffee-ground emesis, persistent vomiting, fever).

- Use a variety of teaching methods (verbal instruction, written materials, visual aids, teach-back method).

- Encourage questions and provide ample time for discussion and clarification.

- Involve family members or caregivers in the education process, as appropriate, to foster a supportive environment.

- Provide reliable resources for further information and support (e.g., reputable websites, support groups).

5. Risk for Perforation or Obstruction

- For Perforation: Monitor for sudden, severe, sharp abdominal pain (often described as "knife-like"), rigid, board-like abdomen, signs of peritonitis (rebound tenderness, guarding), fever, rapid shallow breathing, absent bowel sounds, signs of shock.

- For Obstruction: Monitor for recurrent vomiting (especially undigested food), epigastric fullness, abdominal distention, persistent nausea, weight loss, succussion splash (sound of fluid in stomach upon shaking abdomen).

- Report any signs or symptoms of perforation or obstruction to the physician immediately. These are medical emergencies.

- Maintain NPO status if perforation or obstruction is suspected.

- Prepare for emergency surgery if indicated (for perforation).

- Insert and manage an NG tube for decompression in cases of obstruction or perforation.

- Administer IV fluids and electrolytes as prescribed.

- Monitor fluid and electrolyte balance carefully.

Complications of Peptic Ulcers

While most peptic ulcers heal with appropriate medical management, they can lead to severe and potentially life-threatening complications. Prompt recognition and management of these complications are critical.

- Manifestations:

- Hematemesis: Vomiting of blood. It can be bright red (indicating fresh, active bleeding) or appear as "coffee grounds" (due to blood being partially digested by gastric acid). More common with gastric ulcers.

- Melena: Black, tarry, sticky, foul-smelling stools. This occurs when blood from an upper GI bleed has been digested as it passes through the intestines. More common with duodenal ulcers.

- Hematochezia: Bright red blood from the rectum. While usually indicative of lower GI bleeding, a very rapid upper GI bleed can also present with hematochezia.

- Systemic Signs: Signs of significant blood loss and hypovolemia, such as pallor, dizziness, weakness, tachycardia, and hypotension.

- Mechanism: Spillage of gastric or duodenal contents (acid, pepsin, bile, bacteria, food particles) into the sterile peritoneal cavity.

- Clinical Presentation: Characterized by the sudden onset of excruciating, sharp, and generalized abdominal pain (often described as "knife-like"). The abdomen becomes rigid and board-like due to generalized peritonitis. Other signs include rebound tenderness, guarding, fever, shallow breathing, absent bowel sounds, and signs of shock.

- Management: This is a surgical emergency requiring immediate intervention to close the perforation and wash out the abdominal cavity.

- Clinical Presentation: The pain is often more constant, radiating to the back (if penetrating the pancreas) or other areas depending on the organ involved. It may not be relieved by food or antacids and can be more severe than typical ulcer pain.

- Management: Can be difficult to manage medically and may require surgical intervention.

- Clinical Presentation: Characterized by persistent and recurrent vomiting, often of undigested food ingested hours earlier. Other symptoms include epigastric fullness, abdominal distention, persistent nausea, anorexia, and progressive weight loss. A "succussion splash" (a sloshing sound heard over the stomach) may be elicited.

- Management: Initial management involves gastric decompression (nasogastric tube) and correction of fluid/electrolyte imbalances. Endoscopic balloon dilation may be attempted, but surgery (e.g., pyloroplasty) may be necessary for definitive relief.

Management of a Patient with Severe PUD

Severe Peptic Ulcer Disease, particularly with complications like hemorrhage or perforation, is a medical emergency requiring immediate intervention and comprehensive nursing care.

Aims of Management

- To relieve acute signs and symptoms (e.g., pain, bleeding).

- To treat and control the underlying cause.

- To stabilize the patient's hemodynamic status.

- To prevent further complications.

Emergency Management / Resuscitation

- Maintain ABCs: Ensure a patent Airway, assess Breathing, and support Circulation. Position the patient for comfort and to prevent aspiration if vomiting.

- Call for Help: Immediately notify the doctor or rapid response team about the patient's critical condition.

- Establish IV Access: Secure at least one, preferably two, large-bore IV lines for rapid fluid and medication administration.

- Administer IV Fluids: Start IV fluids, such as Normal Saline, to treat or prevent hypovolemic shock.

- Take Blood Samples: Draw blood for urgent investigations, including CBC, cross-matching for blood transfusion, electrolytes, and coagulation studies.

- Monitor Vital Signs: Take vital observations (temperature, blood pressure, pulse, respiration, and oxygen saturation) frequently (e.g., every 15-30 minutes) to monitor for signs of shock.

- Control Symptoms:

- Administer IV medications to reduce gastric acid secretion (e.g., Rabeprazole 40mg or Ranitidine 150mg).

- Administer analgesics for pain relief as prescribed (e.g., IV Morphine 15mg or Pethidine 100mg). Note: NSAIDs are contraindicated.

- Administer IV antiemetics to control nausea and vomiting (e.g., Metoclopramide 10mg).

- Quick Assessment: Perform a rapid assessment to establish the cause and severity of symptoms (e.g., assess for abdominal rigidity indicating perforation).

- Neutralize Acid: If the patient is conscious, not actively vomiting, and there's no sign of perforation, sips of water or dairy products may be given to help neutralize stomach acids.

After the patient is stabilized, ongoing management will involve the following nursing care plan.

Nursing Care Plan

Admission

The patient is admitted to a medical or surgical ward, placed on complete bed rest, and their particulars are recorded in the ward admission book.

Psychological Care

Establish a good rapport with the patient and their relatives. Provide counseling and reassurance about the condition and treatment plan to allay anxiety.

Position

Nurse the patient in a position of comfort that ensures a patent airway and eases breathing, such as Fowler's or semi-Fowler's position, unless contraindicated by shock.

Observations

- Vital Observations: Continue to monitor BP, pulse, temperature, and respiration as ordered by the doctor and record them on an observation chart.

- Specific/Physical Observations: Continuously observe for:

- Abdominal discomfort, guarding, or rigidity.

- Signs of ongoing bleeding: hematemesis, melena.

- Nausea, vomiting, abdominal bloating.

- Changes in level of consciousness.

- Report the extent and severity of any findings to the doctor immediately.

Investigations

Prepare the patient for and assist with investigations as ordered by the doctor:

- Blood for H. pylori test to identify the cause.

- Stool analysis to rule out occult blood.

- Abdominal CT scan to rule out complications like obstruction or perforation.

- Barium meal to assess for structural abnormalities.

Medications / Drugs

Administer medications as prescribed and maintain an accurate treatment chart. This may include:

- IV Ranitidine or Rabeprazole (PPIs).

- IV antibiotics like Metronidazole.

- Analgesics such as IM Pethidine alternating with IV Paracetamol.

- IV fluids (e.g., Normal Saline alternating with 5% Dextrose, 2-3 litres in 24 hours).

- Antacid syrups (e.g., Relcer gel) once oral intake is resumed.

Diet

The patient may be kept Nil Per Mouth (NPM) initially. Once stable, a light, well-balanced diet is introduced. Encourage plenty of oral fluids to ease digestion and neutralize stomach acids.

Hygiene

Ensure patient hygiene through daily oral care to prevent complications like stomatitis, daily bed baths, and regular turning and pressure area care to prevent pressure sores.

Elimination

- Bladder Care: Offer a bedpan or urinal. Monitor urine output and maintain a fluid balance chart to assess hydration status.

- Bowel Care: Offer a bedpan and observe stool for any abnormalities (e.g., melena), reporting findings to the doctor.

Exercises

Provide passive range-of-motion exercises during the recovery period. As the patient's condition improves, encourage active exercises like ambulation and deep breathing to prevent respiratory and circulatory complications.

Rest and Sleep

Ensure a quiet, restful environment by managing noise and restricting visitors. Administer medications in a timely manner to promote comfort and sleep.

Advice on Discharge

When the patient has fully improved, provide comprehensive discharge education:

- Medication Compliance: Take all drugs as prescribed and complete the full course.

- Diet: Eat a well-balanced diet and consume plenty of fluids, especially water and milk, to neutralize stomach acids. Eat at regular times.

- Lifestyle:

- Avoid alcohol and smoking completely.

- Avoid stress and ensure adequate rest.

- Avoid chronic use of NSAIDs.

- Follow-up: Return for review on the date indicated on the discharge form.