Table of Contents

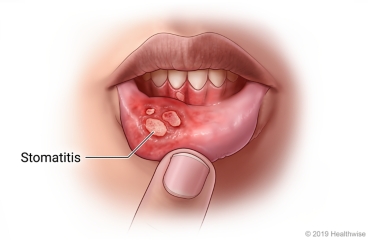

ToggleSTOMATITIS

REVIEW: Anatomy of the Gastrointestinal (GI) Tract

The gastrointestinal (GI) tract is a continuous, hollow, muscular tube that serves as the primary pathway for digestion and absorption. It is approximately 23 to 26 feet (7 to 8 meters) long and extends from the mouth to the anus, passing through the thoracic and abdominopelvic cavities.

Esophagus

Stomach

- Cardia: The entrance area surrounding the esophageal opening.

- Fundus: The rounded upper portion superior and to the left of the cardia.

- Body: The large central portion.

- Pylorus: The lower outlet portion that connects to the small intestine.

- The Lower Esophageal Sphincter (LES) or cardiac sphincter surrounds the esophagogastric junction (inlet). When it contracts, it closes off the stomach from the esophagus, preventing reflux.

- The Pyloric Sphincter is a ring of circular smooth muscle at the junction of the pylorus and the duodenum. It controls the rate at which partially digested food (chyme) leaves the stomach and enters the small intestine.

Small Intestine

- Duodenum: The first and shortest part (about 10 inches), where chyme from the stomach is mixed with bile and pancreatic secretions. The common bile duct and pancreatic duct empty into the duodenum at the ampulla of Vater.

- Jejunum: The middle section, which is the primary site for nutrient absorption.

- Ileum: The final and longest section, which absorbs vitamins (especially B12) and bile salts.

Large Intestine

- Ascending Colon: Travels up the right side of the abdomen.

- Transverse Colon: Extends across the upper abdomen from right to left.

- Descending Colon: Travels down the left side of the abdomen.

Rectum and Anus

- The rectum is the final section of the large intestine, terminating at the anus.

- The anus is the external opening of the GI tract. Its outlet is regulated by the internal and external anal sphincters, which are a network of smooth and striated (voluntary) muscles, respectively.

Blood and Nerve Supply of the GI Tract

Blood Supply

- Arterial blood is supplied by arteries originating from the thoracic and abdominal aorta, primarily the gastric artery (for the stomach) and the superior and inferior mesenteric arteries (for the intestines).

- Venous blood, rich in absorbed nutrients, is drained from these organs by veins that merge to form the hepatic portal vein. This nutrient-rich blood is carried directly to the liver for processing.

- The blood flow to the GI tract is significant, accounting for about 20% of total cardiac output at rest and increasing substantially after eating.

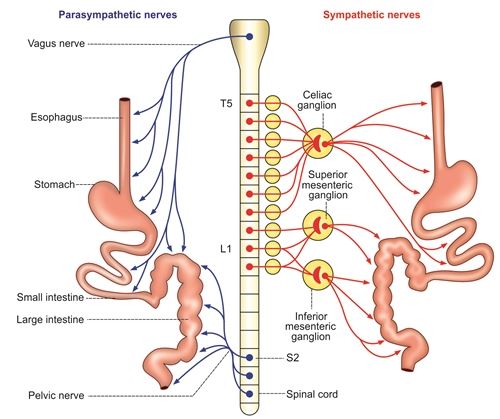

Nerve Supply

- The GI tract is innervated by both the sympathetic and parasympathetic divisions of the autonomic nervous system.

- Sympathetic nerves generally have an inhibitory effect: they decrease gastric secretions and motility, and cause sphincters and blood vessels to constrict.

- Parasympathetic nerves (primarily the vagus nerve) generally have a stimulatory effect: they increase peristalsis and secretory activities, and cause sphincters to relax.

- The only portions of the GI tract under voluntary control are the upper esophagus (for swallowing) and the external anal sphincter (for defecation).

Primary Functions of the Digestive System

- Ingestion & Digestion: To take in food and break it down from complex particles into its molecular form (e.g., carbohydrates into glucose).

- Absorption: To absorb the small molecules produced by digestion into the bloodstream and lymphatic system for use by the body.

- Elimination: To eliminate undigested foodstuffs, unabsorbed nutrients, and other waste products from the body as feces.

General Signs and Symptoms of Digestive System Disorders

- Stomatitis: Inflammation of the mouth (oral mucosa).

- Nausea and Vomiting: Nausea is a feeling of discomfort in the epigastrium with a conscious desire to vomit. Vomiting is the forceful ejection of partially digested food and secretions from the upper GI tract.

- Dysphagia: Difficulty in swallowing.

- Dyspepsia (Indigestion): A symptom complex including post-meal fullness, heartburn, bloating, and possibly nausea.

- Achalasia: Absent or ineffective peristalsis of the distal esophagus, accompanied by the failure of the lower esophageal sphincter to relax in response to swallowing.

- Hematemesis: Bloody vomitus, which can appear as fresh, bright red blood or have a 'coffee ground' appearance (dark, grain-digested blood).

- Melena: Black, tarry, and often foul-smelling stools caused by the digestion of blood in the GI tract. The black appearance is due to the presence of iron.

- Changes in Bowel Habits: This can include:

- Constipation: An abnormal infrequency of defecation or the passage of abnormally hard stools.

- Diarrhea: The passage of 3 or more loose or watery stools in 24 hours.

- Fecal Incontinence: The involuntary passage of stool, which may be due to piles, trauma, surgery, infection, etc.

- Abdominal Distension: Swelling or enlargement of the abdomen.

- Abdominal Pain and Tenderness: Can be diffuse, localized, dull, burning, or sharp.

- Abdominal Rigidity: Involuntary stiffness of the abdominal muscles, often indicating peritoneal irritation.

- Rebound Tenderness: Pain upon removal of pressure rather than application of pressure to the abdomen.

- Decreased or Absent Bowel Sounds: May indicate an ileus or obstruction.

- Tenesmus: A sensation of incomplete bowel emptying.

- Gas or Bloating (Flatulence): Excessive stomach or intestinal gas.

- Jaundice: Yellowish discoloration of the skin and sclera due to elevated bilirubin levels.

- Hepatomegaly/Splenomegaly: Enlargement of the liver and spleen, respectively.

- Pruritus and Urticaria: Itching and hives, which can be associated with liver disorders.

- Shock: Particularly hypovolemic shock, due to fluid or blood loss from the GI tract.

Disorders of the Digestive System

Stomatitis

Stomatitis refers to a broad range of inflammatory conditions affecting the epithelial lining of the oral mucosa, which is the moist membrane that lines the inside of the mouth. This inflammation can manifest in various ways, from mild redness and discomfort to severe ulceration and pain, significantly impacting a person's ability to eat, speak, and maintain oral hygiene. Stomatitis is not a single disease but rather a symptom or a group of symptoms that can arise from a diverse array of local (within the mouth) and systemic (affecting the entire body) factors.

Causes and Etiology of Stomatitis

The etiology of stomatitis is multifaceted, often involving an interplay of various predisposing and precipitating factors. Understanding the underlying cause is crucial for effective diagnosis and management.

Trauma:- Mechanical Injury: This is a common cause, including accidental biting of the cheek or tongue, irritation from sharp or abrasive foods (e.g., hard crackers, bones), ill-fitting dental appliances (braces, dentures), or vigorous toothbrushing.

- Thermal Injury: Burns from hot foods or liquids.

- Chemical Injury: Exposure to irritating chemicals or highly acidic substances.

- Bacterial Infections: Can lead to conditions like acute necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis (ANUG), impetigo affecting the perioral region, or secondary infections of existing lesions.

- Fungal Infections:

- Candida albicans: Most commonly associated with oral thrush, presenting as creamy white patches that can be scraped off, revealing reddened, often bleeding, underlying tissue. It is particularly common in infants, immunocompromised individuals (e.g., HIV/AIDS patients, those undergoing chemotherapy), or those on long-term antibiotic or corticosteroid therapy.

- Viral Infections:

- Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV): Primarily HSV-1, causing primary herpetic gingivostomatitis (especially in children) characterized by widespread oral ulcers, fever, and malaise, or recurrent herpes labialis (cold sores) around the lips.

- Varicella-Zoster Virus (VZV): Causes chickenpox (primary infection) and shingles (reactivation), both of which can involve painful oral lesions.

- Other Viruses: Coxsackievirus (hand, foot, and mouth disease), Epstein-Barr Virus (infectious mononucleosis), and Human Papillomavirus (oral warts).

- Tobacco Use: Smoking, chewing tobacco, and snuff are major irritants, increasing the risk of leukoplakia, erythroplakia, and oral cancers, often preceded by chronic stomatitis.

- Alcohol Consumption: Heavy alcohol use is corrosive to oral tissues and is a significant risk factor for oral lesions and cancers, especially when combined with tobacco.

- Spicy Foods: Can cause temporary irritation and inflammation in sensitive individuals.

- Renal Disorders: Uremic stomatitis can occur in patients with severe kidney failure, characterized by a white, thick, or pseudomembranous coating on the oral mucosa, often with a metallic taste due to urea breakdown products.

- Liver Disorders: Chronic liver disease can lead to oral mucosal changes due to metabolic disturbances.

- Hematologic Disorders:

- Anemia (e.g., iron deficiency anemia, pernicious anemia): Can cause atrophic glossitis (smooth, red, painful tongue), angular cheilitis (cracking at mouth corners), and general oral soreness.

- Leukemia, Agranulocytosis: Can lead to severe gingivitis, ulcerations, and opportunistic infections due to compromised immune function.

- Autoimmune Diseases:

- Pemphigus Vulgaris, Bullous Pemphigoid: Autoimmune blistering diseases that can severely affect the oral mucosa, causing painful erosions.

- Lichen Planus: A chronic inflammatory condition that can present as white lacy patterns, red erosions, or ulcers in the mouth.

- Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE): Oral lesions (ulcers, red patches) can be a feature.

- Crohn's Disease, Ulcerative Colitis (Inflammatory Bowel Diseases): Can cause oral aphthous ulcers or granulomatous lesions.

- Diabetes Mellitus: Poorly controlled diabetes can predispose individuals to candidiasis and other oral infections due to impaired immune response and higher glucose levels in saliva.

- Chemotherapeutic Drugs: Mucositis (a severe form of stomatitis) is a very common and debilitating side effect of many cancer chemotherapeutic agents (e.g., methotrexate, 5-fluorouracil) and radiation therapy to the head and neck, causing widespread painful ulcerations.

- Antibiotics: Can disrupt the normal oral flora, leading to opportunistic infections like candidiasis.

- Anticonvulsants (e.g., phenytoin): Can cause gingival hyperplasia (overgrowth of gum tissue).

- Immunosuppressants: Increase susceptibility to oral infections.

- Other Drugs: Certain antihypertensives, antidepressants, and anti-inflammatory drugs can also cause oral side effects.

- B Vitamins (especially B1, B2, B3, B6, B12, Folate): Deficiencies can lead to glossitis, angular cheilitis, and recurrent aphthous ulcers.

- Iron: Iron deficiency anemia frequently causes atrophic glossitis, oral burning, and angular cheilitis.

- Vitamin C (Ascorbic Acid): Severe deficiency (scurvy) results in swollen, bleeding gums, tooth mobility, and poor wound healing.

- Vitamin A: Important for maintaining healthy epithelial tissues; deficiency can lead to dry mouth and increased susceptibility to infection.

- Zinc: Essential for immune function and wound healing; deficiency can impact oral health.

- Allows for the accumulation of plaque and calculus, leading to gingivitis and periodontitis.

- Promotes the overgrowth of pathogenic microorganisms (bacteria, fungi), increasing the risk of infections.

- Poor Denture Hygiene: Inadequate cleaning allows for biofilm formation and microbial proliferation, particularly Candida species, leading to denture stomatitis (inflammation of the mucosa under the denture).

- Ill-Fitting Dentures: Cause chronic frictional trauma and pressure points, leading to localized inflammation, sores, and hyperplastic tissue reactions.

- Continuous Night-Time Wear: Deprives the underlying mucosa of exposure to saliva and oxygen, creating an environment conducive to microbial growth and inflammation.

- Hormonal Changes: Fluctuations during puberty, menstruation, pregnancy, and menopause can influence oral health and susceptibility to inflammation.

- High Intake of Sugary Foods: Promotes an acidic oral environment and provides substrate for bacterial growth, contributing to dental caries and potentially exacerbating inflammation.

- Stress: Psychological stress can weaken the immune system and has been linked to the exacerbation of conditions like recurrent aphthous stomatitis.

- Allergies: Allergic reactions to dental materials, food components, or oral hygiene products can trigger localized inflammatory responses.

- Genetic Predisposition: Some individuals may be genetically more prone to certain types of stomatitis, such as recurrent aphthous ulcers.

Clinical Manifestations of Stomatitis

The signs and symptoms of stomatitis vary depending on the cause, location, and severity of the inflammation, but commonly include:

- Changes in Salivation: Can range from excessive salivation (sialorrhea), often due to irritation or pain, to pronounced dryness of the mouth (xerostomia), which can exacerbate discomfort and increase infection risk.

- Halitosis (Bad Breath): A common symptom, resulting from bacterial overgrowth, tissue breakdown, or metabolic products associated with certain systemic diseases.

- Glossitis: Inflammation of the tongue, causing it to appear red, swollen, smooth (due to atrophy of papillae), and often exquisitely painful. This can be a sign of nutritional deficiencies (e.g., B vitamins, iron) or systemic diseases.

- Oral Ulcers: Painful, open sores that can occur on any part of the oral mucosa, including the gums, palate, buccal mucosa (inner cheeks), and lips. These can range from small aphthous ulcers to large, irregular erosions characteristic of viral infections or autoimmune conditions.

- Thrush (Oral Candidiasis): Characterized by creamy white, cottage-cheese-like patches on the tongue, inner cheeks, palate, or throat. These lesions are typically adherent but can be scraped off, revealing an erythematous (red) and sometimes bleeding base. It is a hallmark of fungal infection, especially in immunocompromised or debilitated individuals (e.g., infants, HIV/AIDS patients, those on prolonged antibiotics or corticosteroids).

- Gingivitis: Swelling, redness, and bleeding of the gums, often an early sign of periodontal disease but can also be part of a generalized stomatitis.

- Denture Stomatitis: A specific form of inflammation seen in denture wearers, presenting as reddening and sometimes swelling of the mucosa directly under the denture-bearing area, often associated with a fungal infection.

- Dysphagia and Odynophagia: Difficulty and pain during swallowing, respectively, especially if the inflammation extends to the throat or pharynx.

- Dysgeusia: Altered taste sensation.

- Pain and Discomfort: Ranging from a mild burning sensation to severe, constant pain that interferes with eating and speaking.

Investigations and Diagnosis

Diagnosing stomatitis involves a thorough clinical examination and, often, specific laboratory tests to identify the underlying cause.

Mouth Swab: A sample taken from the affected area for:- Microscopy: Direct visualization of microorganisms (e.g., fungal hyphae in candidiasis).

- Culture and Sensitivity: To grow and identify bacterial or fungal pathogens and determine their susceptibility to various antimicrobial agents.

- PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) or Viral Culture: To detect viral DNA/RNA (e.g., HSV).

- Complete Blood Count (CBC): To check for signs of anemia, infection, or other hematologic abnormalities.

- Nutritional Deficiencies: Serum levels of vitamins (e.g., B12, folate) and minerals (e.g., iron, ferritin).

- Inflammatory Markers: ESR (Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate) or CRP (C-reactive protein) if systemic inflammation is suspected.

- Rapid Plasma Reagin (RPR) or VDRL: Blood tests for syphilis, which can cause oral lesions (e.g., mucous patches, gummas).

- HIV Serology: To rule out HIV/AIDS, as these patients are highly susceptible to recurrent and severe oral infections, particularly candidiasis and herpes.

- Random Blood Sugar (RBS) or HbA1c: To screen for or monitor diabetes, as hyperglycemia can promote fungal growth and impair healing.

- Liver and Kidney Function Tests: To assess for underlying systemic diseases (e.g., uremic stomatitis).

- Autoantibody Tests: If an autoimmune condition is suspected (e.g., ANA for SLE, anti-desmoglein for pemphigus).

Treatment and Management Strategies

Effective management of stomatitis is multimodal, focusing on treating the underlying cause, alleviating symptoms, and preventing recurrence.

Treat the Underlying Cause: This is the cornerstone of effective therapy. Antimicrobial Therapy:- Broad-spectrum Antibiotics: For identified bacterial infections (e.g., metronidazole for ANUG).

- Antifungals: For oral candidiasis, systemic antifungals (e.g., fluconazole, itraconazole) may be necessary for widespread or resistant infections, in addition to topical agents.

- Antivirals: For severe or recurrent viral infections (e.g., acyclovir, valacyclovir for HSV).

- Saline Rinses: Rinsing the mouth 3-4 times a day with a warm salt solution (e.g., 1/2 teaspoon of salt in 1 cup of warm water) helps to soothe inflamed tissues, cleanse the mouth, and promote healing.

- Antiseptic Mouthwashes:

- Hydrogen Peroxide Solution (6%): Diluted (e.g., 15 ml in 200 ml of warm water) can be used as an oxygenating rinse, particularly beneficial for anaerobic infections and debridement.

- Chlorhexidine Mouthwash (0.2%): An effective broad-spectrum antiseptic, used twice daily, helps reduce bacterial load and plaque formation. Note: Can cause temporary tooth staining with prolonged use.

- Gentle Brushing: Using a soft-bristled toothbrush and non-irritating toothpaste to clean teeth and gums gently, avoiding affected areas if too painful initially.

- Remove Dentures at Night: Allows the oral mucosa to rest and be exposed to saliva and oxygen.

- Improve Denture Hygiene: Regular cleaning by brushing the denture and soaking it daily in an appropriate denture cleanser (e.g., hypochlorite cleanser – 10 drops of household bleach in a cup of water, or commercial denture tablets). The fitting surface of the denture should also be brushed to remove accumulated plaque and fungi.

- Replace Ill-Fitting Dentures: Essential to eliminate chronic trauma and pressure points.

- Reduce Irritants: Avoid highly acidic, spicy, salty, or very hot/cold foods and beverages that can irritate inflamed mucosa.

- Soft, Bland Diet: Encourage consumption of soft, bland, and nutrient-dense foods (e.g., mashed potatoes, soft cooked vegetables, pureed soups, yogurt) to ensure adequate nutrition without causing further discomfort.

- Reduce Sugar Intake: Especially important in cases of candidiasis, as sugar promotes fungal growth.

- Hydration: Drink plenty of fluids to maintain oral moisture and prevent dehydration.

- Antifungals:

- Nystatin Suspension (100,000 IU/mL): A common topical antifungal for oral thrush. Typically, the patient is instructed to "swish and swallow" 5-10 ml 4-6 times daily for 7-14 days (or at least 48 hours after symptoms resolve). The "swish and swallow" method ensures contact with the oral mucosa and allows some medication to reach the esophagus if candidiasis has extended.

- Clotrimazole Troches: Lozenges that dissolve slowly in the mouth, providing prolonged contact time with the oral mucosa.

- Topical Medications:

- Topical Anesthetics: Viscous lidocaine or benzocaine preparations can be applied directly to painful ulcers before meals to allow for easier eating.

- Corticosteroids: Topical steroids (e.g., triamcinolone acetonide in an adhesive paste) can be used for non-infectious inflammatory conditions like aphthous ulcers or lichen planus to reduce inflammation and promote healing.

- Protective Barriers: Over-the-counter gels or rinses that form a protective barrier over ulcers, shielding them from irritation.

- Analgesics (Pain Relievers):

- Systemic Analgesics: Over-the-counter pain relievers like Paracetamol (acetaminophen) (e.g., 500mg or 1g every 4-6 hours, not exceeding daily maximums) or NSAIDs (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs like ibuprofen) can help manage pain and inflammation, especially in widespread or severe cases. Duration of use typically 3 to 5 days, or as directed by a healthcare professional.

- Topical Analgesics: As mentioned above, for localized pain relief.

- Sialagogues: If xerostomia is a significant issue, medications or products that stimulate saliva flow (e.g., pilocarpine) or artificial saliva substitutes may be beneficial.

Complications of Stomatitis

If left untreated or improperly managed, stomatitis can lead to a range of complications that can significantly impact a patient's health and quality of life. These complications can be localized to the oral cavity or have systemic repercussions.

- Difficulty and pain upon eating lead to reduced food intake.

- This can result in significant weight loss, dehydration, and deficiencies in essential macro and micronutrients, particularly in children, elderly, or already debilitated individuals.

- In severe cases, it may necessitate alternative feeding methods like nasogastric tube feeding.

- Uncontrolled local infections (bacterial, fungal, viral) can spread beyond the oral cavity to adjacent structures (e.g., pharynx, esophagus, larynx) or even enter the bloodstream (sepsis), leading to more severe systemic infections, particularly in immunocompromised patients.

- Oral candidiasis can extend to cause esophagitis.

- Chronic pain and difficulty with eating and speaking can lead to social isolation, anxiety, and depression.

- Halitosis associated with stomatitis can also cause embarrassment and affect self-esteem.

- Difficulty with brushing and flossing due to pain can lead to increased plaque accumulation, gingivitis, and progression to periodontitis (gum disease) and dental caries.

- Chronic inflammation can sometimes lead to precancerous lesions, especially if associated with irritants like tobacco and alcohol, or certain infectious agents (e.g., HPV).

Prevention of Stomatitis

Preventing stomatitis involves addressing the predisposing factors and maintaining optimal oral and general health. A proactive approach is key.

- Regular Brushing: Brush teeth at least twice daily with a soft-bristled toothbrush and fluoride toothpaste.

- Flossing: Floss daily to remove plaque and food particles from between teeth and under the gum line.

- Antiseptic Mouthwashes: Use non-alcohol based mouthwashes as recommended by a dental professional, especially if prone to gum inflammation.

- Tongue Cleaning: Gently clean the tongue to remove bacteria and food debris.

- Visit the dentist at least twice a year for professional cleaning and examination.

- Early detection and management of dental problems (e.g., cavities, gum disease) and ill-fitting restorations can prevent irritation.

- Remove dentures at night to allow oral tissues to rest.

- Clean dentures daily using a denture brush and appropriate cleanser.

- Ensure dentures fit well and are relined or replaced as needed to prevent trauma and pressure sores.

- Consume a diet rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and lean proteins to ensure adequate intake of essential vitamins and minerals, especially B vitamins, iron, zinc, and vitamin C.

- Consider nutritional supplements if dietary intake is insufficient or if specific deficiencies are identified.

- Tobacco and Alcohol: Abstain from or significantly reduce the use of tobacco products (smoking, chewing) and limit alcohol consumption, as these are major contributors to oral inflammation and malignancy.

- Spicy and Acidic Foods: If prone to irritation, limit intake of excessively spicy, acidic, or abrasive foods.

- Avoid Very Hot Beverages: Allow hot drinks to cool slightly before consuming.

- Effectively manage chronic diseases such as diabetes, autoimmune disorders, and kidney disease, as good control can prevent oral manifestations.

- Be aware of potential oral side effects of medications.

- If undergoing chemotherapy or radiation to the head and neck, follow all recommended mucositis prevention protocols (e.g., cryotherapy, specific rinses).