Urinary Tract Infections (UTIs)

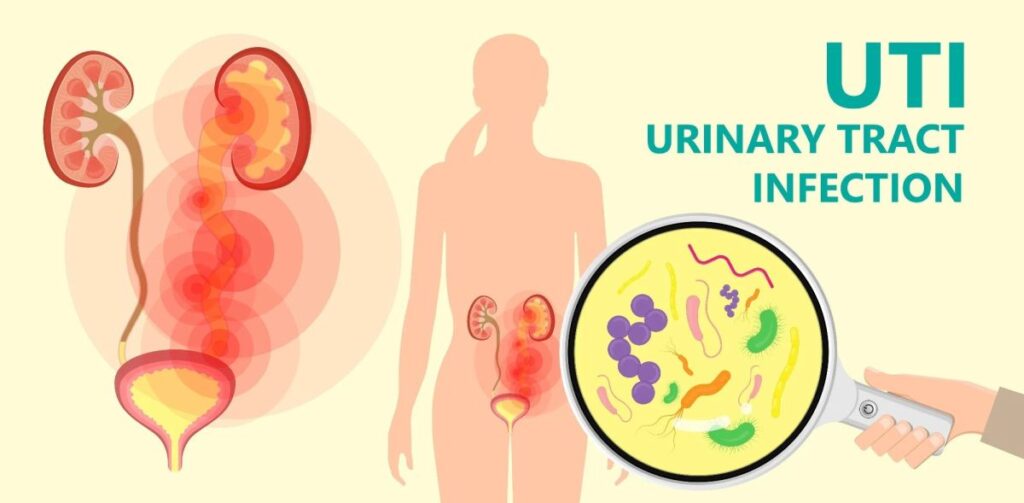

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are bacterial infections that can occur in any part of the urinary system, including the kidneys, bladder, ureters, and urethra.

The most common cause of UTIs is the colonization of bacteria from the gastrointestinal tract, with Escherichia coli (E. coli) being the most frequently implicated pathogen. Other pathogens that can cause UTIs include Klebsiella, Proteus, Enterococcus, and Staphylococcus species.

At its core, a UTI is defined as an infection in any part of the urinary system. This system, responsible for filtering waste and producing urine, comprises several key organs:

- Kidneys: These bean-shaped organs are the primary filters of the blood, removing waste products and excess fluid to form urine.

- Ureters: These are thin tubes that transport urine from each kidney to the bladder.

- Bladder: A muscular sac that stores urine until it’s ready to be expelled from the body.

- Urethra: The tube that carries urine from the bladder out of the body during urination.

While UTIs can occur in any part of this system, the majority of infections are localized in the lower urinary tract, specifically involving the bladder (cystitis) and the urethra (urethritis). Infections affecting the kidneys are termed pyelonephritis and represent a more serious form of UTI.

Prevalence of Urinary Tract Infections

UTIs are significantly more prevalent in women than in men, particularly in the younger to middle-aged adult population (20-50 years). In this age bracket, women are approximately 50 times more likely to develop a UTI compared to men. This striking difference is primarily attributed to anatomical differences, specifically the shorter urethra in females, which allows bacteria easier access to the bladder.

However, the landscape of UTI prevalence shifts with age. While UTI incidence increases in both sexes beyond 50 years of age, the female-to-male ratio decreases. This is largely due to the increasing occurrence of prostate enlargement (benign prostatic hyperplasia – BPH) and instrumentation (medical procedures involving insertion of instruments into the urethra) in men as they age. BPH can lead to urinary retention, and instrumentation can introduce bacteria, both increasing UTI risk in men.

Specific Types of UTIs based on Location and Demographics:

- Women (20-50 years): The most common types of UTIs in this group are cystitis (bladder infection) and pyelonephritis (kidney infection). These are often considered “uncomplicated” UTIs in otherwise healthy, non-pregnant women without structural urinary tract abnormalities.

- Men (20-50 years): In men of the same age, UTIs are less frequent but often present as urethritis (urethral infection) or prostatitis (prostate infection). UTIs in men are generally considered more complex and require thorough evaluation.

- Older Adults (>50 years): The incidence of UTIs increases in both sexes. In women, cystitis and pyelonephritis remain common. In men, alongside urethritis and prostatitis, UTIs may become associated with BPH and require careful management.

Risk Factors for Urinary Tract Infections

UTIs develop when bacteria, usually from the bowel, enter the urinary tract and multiply. Several factors can compromise the body’s natural defenses and increase the likelihood of bacterial colonization and infection. These risk factors can be broadly categorized:

1. Iatrogenic/Drugs (Medical Procedure or Medication Related):

- Indwelling Catheters: These tubes, inserted into the urethra to drain urine, provide a direct pathway for bacteria to enter the bladder. Catheter-associated UTIs (CAUTIs) are a significant concern, especially in hospitalized patients.

- Antibiotic Use: While antibiotics treat infections, their overuse can disrupt the normal, protective bacterial flora in the vagina and bowel. This disruption can allow pathogenic bacteria (like E. coli, a common UTI culprit) to flourish and colonize the urinary tract more easily.

- Spermicides: These chemicals, used for contraception, can irritate the vaginal area and alter the normal vaginal flora, increasing susceptibility to UTI.

2. Behavioral Factors:

- Voiding Dysfunction: Conditions or habits that prevent complete bladder emptying, such as infrequent urination or bladder muscle problems, can lead to post-void residual urine. This stagnant urine provides a breeding ground for bacteria.

- Frequent or Recent Sexual Intercourse: Sexual activity can introduce bacteria into the urethra, particularly in women. “Honeymoon cystitis” is a term sometimes used to describe UTIs related to increased sexual activity.

3. Anatomic/Physiologic Factors:

- Vesicoureteral Reflux (VUR): This condition involves the abnormal backflow of urine from the bladder into the ureters and sometimes up to the kidneys. VUR causes urinary retention, giving bacteria more time to grow. The retrograde flow also allows bacteria to ascend higher into the urinary tract, potentially reaching the kidneys.

- Female Sex: As mentioned, the shorter urethra in females makes it easier for bacteria from the perineal area to reach the bladder.

- Pregnancy: Hormonal changes during pregnancy, particularly increased progesterone, cause smooth muscle relaxation in the bladder and ureters. Additionally, the growing uterus can compress the ureters. Both these factors can lead to urinary retention, increasing the risk of UTI.

4. Genetic Predisposition:

- Familial Tendency: There’s evidence suggesting a genetic component to UTI susceptibility, as UTI occurrence can cluster in families.

- Susceptible Uroepithelial Cells: The cells lining the urinary tract (uroepithelial cells) play a role in defense against infection. Some individuals may have uroepithelial cells that are more susceptible to bacterial adhesion and invasion.

- Vaginal Mucus Properties: The properties of vaginal mucus, including its composition and viscosity, can influence the ability of E. coli to bind and colonize.

Pathophysiology of Urinary Tract Infections

- Colonization: The process often begins with bacteria, typically from the bowel flora, colonizing the periurethral area (the skin around the urethral opening). These bacteria then ascend through the urethra, moving upwards towards the bladder. E. coli is the most frequent culprit in uncomplicated UTIs due to its ability to adhere to uroepithelial cells.

- Uroepithelium Penetration: Certain bacterial features, like fimbriae (pili), act as adhesion molecules. Fimbriae allow bacteria to attach to and penetrate the bladder’s epithelial cells. After penetration, bacteria can replicate within the bladder lining and may form biofilms, communities of bacteria encased in a protective matrix, making them harder to eradicate.

- Ascension: If the infection is not contained at the bladder level, bacteria can ascend further up the urinary tract, moving through the ureters towards the kidneys. Factors like VUR can facilitate this ascension. Bacterial toxins may also inhibit peristalsis (the rhythmic contractions of the ureters that help move urine downwards), reducing urine flow and aiding bacterial ascent.

- Pyelonephritis: When bacteria reach the kidneys and infect the renal parenchyma (the functional tissue of the kidney), it triggers an inflammatory response known as pyelonephritis. This kidney infection can be severe. While usually caused by ascending bacteria, pyelonephritis can also result from hematogenous spread – bacteria traveling from another infection site in the body through the bloodstream to the kidneys (though this is less common in typical UTIs).

- Acute Kidney Injury: If the inflammatory cascade in the kidney continues unchecked, it can lead to tubular obstruction (blockage of the kidney tubules) and tissue damage, resulting in interstitial edema (swelling in the kidney tissue). This process can progress to interstitial nephritis, ultimately causing acute kidney injury (AKI).

Etiology of Urinary Tract Infections

Common Bacterial Culprits

The vast majority of UTIs are caused by bacteria. Identifying the common culprits is crucial for effective treatment.

Most Frequent Cause (Enteric Gram-Negative Aerobic Bacteria):

- Escherichia coli (E. coli): This bacterium is the dominant cause, responsible for 75-95% of cystitis and pyelonephritis cases in uncomplicated UTIs. E. coli is a normal inhabitant of the bowel but can become pathogenic when it enters the urinary tract.

- Klebsiella species: Another common gram-negative bacterium found in the gut.

- Proteus mirabilis: Known for its ability to produce urease, an enzyme that can raise urine pH, potentially leading to the formation of struvite kidney stones.

- Pseudomonas aeruginosa: While less common in uncomplicated UTIs, Pseudomonas is more frequently seen in catheter-associated infections and complicated UTIs, often exhibiting antibiotic resistance.

Less Frequent Cause (Gram-Positive Bacteria):

- Staphylococcus saprophyticus: This gram-positive coccus is a significant cause of UTIs, particularly in young, sexually active women (5-10% of bacterial UTIs in this group).

- Enterococcus faecalis (Group D streptococci): Enterococci are becoming increasingly important UTI pathogens, especially in hospitalized patients and those with complicated UTIs.

- Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B streptococci): While primarily known for neonatal infections, Group B strep can also cause UTIs in adults, including pregnant women.

Clinical Presentation: Signs and Symptoms of Urinary Tract Infections

The symptoms of a UTI vary depending on the location of the infection within the urinary tract.

1. Kidney Infection (Acute Pyelonephritis): Symptoms are typically more systemic and severe:

- Upper back and side (flank) pain: Pain is often localized to the area of the affected kidney.

- High fever: Elevated body temperature is a common sign of systemic infection.

- Shaking chills: Rigors, or uncontrollable shaking, can accompany fever.

- Nausea and Vomiting: Gastrointestinal symptoms are frequent.

- General malaise and fatigue: Feeling unwell and weak.

2. Bladder Infection (Cystitis): Symptoms are more localized to the lower urinary tract:

- Pelvic pressure: A feeling of discomfort or fullness in the lower pelvis.

- Lower abdomen discomfort: Pain or cramping in the lower abdomen.

- Frequent, painful urination (dysuria): A hallmark symptom of cystitis, characterized by urgency and pain during urination.

- Blood in urine (hematuria): Urine may appear pink, red, or tea-colored due to blood.

- Suprapubic tenderness: Pain when pressing on the area just above the pubic bone.

3. Urethral Infection (Urethritis): Primarily characterized by:

- Burning with urination: Pain and a burning sensation during urination.

- Discharge: Urethral discharge may be present, especially if the urethritis is sexually transmitted.

Classification of UTIs: Uncomplicated vs. Complicated

UTIs are broadly classified into uncomplicated and complicated, which has significant implications for management.

Uncomplicated UTI:

- Typically occurs in premenopausal adult women.

- No underlying structural or functional abnormalities of the urinary tract.

- Not pregnant.

- No significant comorbidities (other health conditions) that would increase the risk of treatment failure or serious outcomes.

- Usually involves cystitis or pyelonephritis in this specific demographic.

Complicated UTI:

A UTI is considered complicated if any of the following are present:

Patient Demographics:

- Child: UTIs in children require different considerations.

- Pregnancy: Pregnancy significantly alters UTI management.

- Male Sex: UTIs in men are generally considered complicated due to the potential for underlying prostate involvement.

- Any Age Beyond Premenopausal Women: UTIs in older individuals or those outside the typical demographic for uncomplicated UTI often have underlying factors.

Underlying Conditions:

- Structural or Functional Urinary Tract Abnormality: Conditions like kidney stones, obstructions, neurogenic bladder, or VUR can complicate UTIs.

- Comorbidities Increasing Infection Risk: Conditions such as poorly controlled diabetes, chronic kidney disease, immunocompromised states (e.g., HIV, organ transplant recipients), or sickle cell disease increase the complexity of UTI management.

- Recent Instrumentation or Surgery of the Urinary Tract: Procedures like cystoscopy or urological surgery can introduce bacteria and complicate UTI.

Diagnosis of Urinary Tract Infection

Urine Collection: Proper urine collection is essential to avoid contamination and ensure accurate results.

- Clean-catch, Midstream Specimen: This is the preferred method for routine UTI diagnosis. Patients are instructed to clean the genital area, start urinating, and then collect the mid-portion of the urine stream into a sterile container, avoiding the initial and final portions. This helps minimize contamination from the urethra and surrounding skin.

- Specimen Obtained by Catheterization: In certain situations, such as in patients unable to void voluntarily or those with indwelling catheters, urine may be collected directly through catheterization. This method is more invasive but can be necessary for specific patient populations.

- Urethral Swab for STD Testing (if suspected): If a sexually transmitted infection (STD) is suspected as a cause of urethritis (e.g., in men with urethral discharge), a urethral swab for STD testing should be obtained prior to voiding to avoid washing away the organisms.

Urine Testing:

Dipstick Tests: These are rapid, point-of-care tests that can provide preliminary information about urine.

- Nitrate Positive: A positive nitrate test is highly specific for UTI. Many bacteria, especially gram-negative bacteria like E. coli, can convert nitrates (normally present in urine) to nitrites. However, the nitrate test is not very sensitive; a negative result doesn’t rule out UTI.

- Leukocyte Esterase Test: This test detects leukocyte esterase, an enzyme released by white blood cells (leukocytes). A positive leukocyte esterase test is very specific for the presence of increased white blood cells (> 10 WBCs/µL) in the urine, indicating inflammation, and is fairly sensitive for UTI.

Microscopic Examination: Microscopic analysis of urine sediment provides more detailed information.

- Pyuria: The presence of white blood cells in urine is called pyuria. Most truly infected patients have pyuria with > 10 WBCs/µL. Pyuria is a key indicator of UTI, but it can also be present in other inflammatory conditions of the urinary tract.

- Bacteria: The presence of bacteria in urine (bacteriuria) is another important finding. However, bacteria can be present due to contamination during sampling, even without a true UTI. If bacteria are seen without pyuria, contamination is more likely.

- Microscopic Hematuria: Small amounts of blood in the urine (microscopic hematuria) are common in UTIs, occurring in up to 50% of patients. Gross hematuria (visible blood in urine) is less common.

- WBC Casts: These are cylindrical structures formed in the kidney tubules and composed of white blood cells. WBC casts suggest kidney involvement and can be seen in pyelonephritis, glomerulonephritis, and noninfective tubulointerstitial nephritis.

Urine Culture: A urine culture is the gold standard for confirming UTI and identifying the specific bacteria causing the infection. It involves growing bacteria from the urine sample in a lab to determine the type of bacteria and its quantity. Culture is particularly recommended in:

- Complicated UTIs: To guide antibiotic selection in complex cases.

- Pregnant women: Due to the significance of UTI in pregnancy.

- Postmenopausal women: Often have more complex UTIs.

- Men: UTIs in men are generally considered complicated.

- Prepubertal children: Require careful evaluation and culture.

- Patients with urinary tract abnormalities or recent instrumentation: To identify unusual pathogens or resistant organisms.

- Patients with immunosuppression or significant comorbidities: Increased risk of treatment failure or resistant infections.

- Patients with symptoms suggesting pyelonephritis or sepsis: To guide appropriate antibiotic therapy for severe infections.

- Patients with recurrent UTIs (≥ 3/year): To identify potential underlying causes and guide preventive strategies.

Urinary Tract Imaging: Imaging studies are not routinely needed for simple cystitis but are indicated in certain situations to assess for structural abnormalities or complications.

Ultrasound, CT Scan, IVU (Intravenous Urogram): These are common imaging choices for evaluating the urinary tract.

Voiding Cystourethrography (VCUG), Retrograde Urethrography, Cystoscopy: These more specialized procedures may be warranted in specific cases to visualize the urethra, bladder, and assess for reflux or obstructions.

Indications for Imaging in Adults:

- ≥ 2 Episodes of Pyelonephritis: Recurrent kidney infections may suggest underlying anatomical issues.

- Complicated Infections: Imaging helps assess for structural factors contributing to complicated UTIs.

- Suspected Nephrolithiasis (Kidney Stones): Stones can predispose to UTI and cause obstruction.

- Painless Gross Hematuria or New Renal Insufficiency: These findings may indicate more serious underlying conditions.

- Fever Persists for ≥ 72 hours Despite Antibiotics: Suggests possible complications or antibiotic resistance.

- Children with UTI: Often require imaging to rule out congenital urinary tract abnormalities, especially VUR.

Types of Urinary Tract Imaging and Their Uses:

KUB Ultrasound (First-line, Non-invasive) | MCUG (Contrast Radiographic Imaging) | Nuclear Scans (DMSA & MAG3 Radioisotope) |

Uses Assess: Fluid collections, Bladder volume, Kidney size/shape/location, Urinary tract obstructions/dilatations | Uses Confirm: Posterior urethral valves, Obstructive Uropathies, Gold standard for VUR diagnosis | Uses Confirm: Suspicion of renal damage, DMSA: Gold standard for renal scar detection, MAG3: Faster/less radiation, Renal excretion enables micturition study |

Indications – Concurrent bacteremia, | Indications – Abnormal renal ultrasound (Hydronephrosis, Thick bladder wall, Renal scarring), | Indications – Clinical suspicion of renal injury, |

Limitations Does not assess function, Operator dependent, Cannot diagnose VUR | Limitations Radiation exposure ~1 mSv, Invasive, Unpleasant post-infancy, May need sedation, Requires prophylactic antibiotics | Limitations Dynamic renal excretion study requires toilet training, False positives if <3 months post-UTI (not for acute phase), May need sedation, Cannot determine old vs. new scarring |

- KUB-Ultrasound of Kidney, ureters and bladder also known as ultrasound KUB

- MCUG-Micturating Cystogram

Differential Diagnosis of Urinary Tract Infection

- Acute Urethral Syndrome (in women): This syndrome involves dysuria, frequency, and pyuria, mimicking cystitis. However, unlike cystitis, routine urine cultures in acute urethral syndrome are often negative. Causative organisms may be different or the inflammation may be non-infectious.

- Urethritis (non-bacterial): Urethritis can be caused by sexually transmitted infections like Chlamydia trachomatis and Ureaplasma urealyticum. These organisms are not typically detected on routine urine cultures for bacterial UTI. STD testing is essential in sexually active individuals with urethritis symptoms.

- Noninfectious Causes: Several non-infectious conditions can mimic UTI symptoms:

- Anatomic abnormalities: Urethral stenosis (narrowing).

- Physiologic abnormalities: Pelvic floor muscle dysfunction.

- Hormonal imbalances: Atrophic urethritis (common in postmenopausal women due to estrogen deficiency).

- Localized trauma: Injury to the urethra or bladder.

- Gastrointestinal (GI) system symptoms and inflammation: Conditions like appendicitis or inflammatory bowel disease can sometimes present with urinary symptoms.

Management of Urinary Tract Infections

UTI management depends on the type of UTI (uncomplicated vs. complicated), location of infection, patient demographics, and presence of underlying conditions.

Urethritis Management: For sexually active patients with urethritis symptoms, presumptive treatment for STDs is often initiated while awaiting test results. This is because STDs are common causes of urethritis in this population.

Typical Regimen: Combination therapy targeting common STDs:

- Ceftriaxone 250 mg IM (intramuscular) single dose (to cover gonorrhea).

- Plus either Azithromycin 1 g PO (oral) once or Doxycycline 100 mg PO bid (twice daily) for 7 days (to cover chlamydia).

Cystitis Management (Uncomplicated Cystitis in Non-pregnant Women):

First-line treatment: Short-course antibiotic therapy is usually effective.

- Nitrofurantoin 100 mg PO bid for 3 days: A commonly used first-line agent. Contraindicated if creatinine clearance is < 60 mL/min (impaired kidney function).

- Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (TMP/SMX) 160/800 mg PO bid for 3 days: Another effective option, but resistance rates may be a concern in some areas.

Acute Pyelonephritis Management: Pyelonephritis necessitates antibiotic treatment.

Outpatient vs. Inpatient Treatment: Outpatient oral antibiotic therapy is possible if all of the following criteria are met:

- Patient is expected to be adherent to treatment.

- Patient is immunocompetent.

- Patient has no nausea or vomiting, or evidence of volume depletion or septicemia (signs of severe infection).

- Patient has no factors suggesting complicated UTI.

Outpatient Oral Antibiotic Options:

- Ciprofloxacin 500 mg PO bid for 7 days: A quinolone antibiotic effective for pyelonephritis.

- Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (TMP/SMX) 160/800 mg PO bid for 14 days: A longer course is often used for pyelonephritis compared to cystitis.

Alternative Management : These are not primary treatments for active infections but may provide symptomatic relief or supportive care.

- Cranberry Concentrates (for adults): May help prevent recurrent UTIs, but evidence for treating active infections is limited.

- Increase Fluid Intake: Drinking plenty of water helps dilute urine and flush out bacteria.

- Ural (urine alkaliniser): May help reduce urinary discomfort by making urine less acidic.

Management in Specific Patient Groups:

Children:

- Infants <3 months with fever (T≥38°C): Refer urgently to paediatrics. These infants require prompt evaluation and likely intravenous antibiotics due to the risk of serious infection.

- Infants 3 months to 3 years with fever (T≥38°C): Assess for UTI. Consider urine MCS (microscopy, culture, sensitivity) and broad-spectrum antibiotics (IV or PO) +/- IV fluids if UTI is suspected. Paediatric referral may be needed.

- Febrile children >3 years: Urinalysis is the first step. Dipstick results (nitrites and leukocyte esterase) can guide management. Urine culture is often needed. Treatment strategies range from oral antibiotics to IV antibiotics depending on clinical severity and dipstick findings.

- Antibiotics for Children: Common antibiotics and therapeutic doses for children include:

- Trimethoprim (TMP) ‘Alprim’: 4 mg/kg BD (twice daily), Max 150 mg BD.

- Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) ‘Bactrim’: 4 + 20 mg/kg BD, Max: 160 + 180 mg BD.

- Cephalexin ‘Keflex’: 12.5mg/kg QID (four times daily), Max: 500 mg QID.

- Amoxicillin and Clavulanic acid ‘Augmentin’: 22.5 + 3.2 mg/kg BD, Max: 875 + 125 mg BD.

- Nitrofurantoin ‘Macrodantin’: Not generally recommended for therapeutic UTI treatment in children.

Adults:

Non-pregnant Women:

- Empirical treatment: Consider for healthy women <65 years with severe or ≥ 3 UTI symptoms.

- Dipstick tests: Guide treatment decisions for healthy women <65 years with mild or ≤2 UTI symptoms.

- Treat symptomatic LUTI (lower UTI) with a 3-day course of trimethoprim or nitrofurantoin. Exercise caution with nitrofurantoin in the elderly due to potential toxicity.

- Obtain urine culture if treatment fails or to guide antibiotic change.

Pregnant Women:

- Screen for asymptomatic bacteriuria: Standard quantitative urine culture at the first antenatal visit. Confirm with a second culture.

- Do not use dipstick testing to screen for UTI in pregnancy.

- Treat asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnant women with antibiotics.

- Treat symptomatic UTI in pregnant women with antibiotics.

- Obtain urine culture before starting empiric antibiotics.

- 7-day course of treatment (amoxicillin, cephalexin, augmentin) is usually sufficient.

- Urine culture for test of cure 7 days after completing antibiotic treatment.

Men:

- UTIs in men are generally considered complicated.

- Consider conditions like prostatitis, chlamydial infection, and epididymitis in the differential diagnosis.

- Urine culture is always recommended in men with UTI symptoms.

- Quinolones (ciprofloxacin) are preferred antibiotics due to their ability to penetrate prostatic fluid. Nitrofurantoin and cephalosporins are less effective for prostate infections.

- Treat bacterial UTI empirically with a quinolone in men with symptoms suggestive of prostatitis.

- 4-week course of antibiotics is appropriate for prostatitis.

- Refer men for urological investigation if they have upper UTI symptoms, fail to respond to antibiotics, or have recurrent UTIs.

Patients on Catheter:

- Do not rely on classical UTI symptoms for diagnosis in catheterized patients. Symptoms may be subtle.

- Signs suggestive of catheter-associated UTI (CAUTI): New onset or worsening fever, rigors, altered mental status, malaise, lethargy, flank pain, costovertebral angle tenderness, acute hematuria.

- Do not use dipstick testing to diagnose UTI in catheterized patients.

- Do not treat asymptomatic bacteriuria in catheterized patients.

- Do not routinely prescribe antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent symptomatic UTI in patients with catheters.

Prevention of UrinaryTract Infections

- Lifestyle measures can help reduce the risk of UTIs, especially recurrent infections.

- Drink plenty of liquids, especially water: Helps flush out bacteria.

- Drink cranberry juice: May prevent bacterial adhesion (evidence is mixed).

- Wipe from front to back after using the toilet: Prevents fecal bacteria from reaching the urethra (for women).

- Empty your bladder soon after intercourse: Helps flush out bacteria that may have entered the urethra.

- Avoid potentially irritating feminine products: Douches, powders, and sprays can disrupt vaginal flora.

- Change your birth control method: Consider alternatives to spermicides or diaphragms if recurrent UTIs are related.

- Prophylaxis for Recurrent UTIs (in women experiencing ≥ 3 UTIs/year):

- Behavioral measures are first-line. If unsuccessful, antibiotic prophylaxis may be considered.

- Continuous Prophylaxis: Low-dose antibiotics taken daily or several times per week. Typically starts with a 6-month trial, may be extended if UTIs recur.

– TMP/SMX 40/200 mg PO once/day or 3 times/week.

– Nitrofurantoin 50 or 100 mg PO once/day.

– Cephalexin 125 to 250 mg PO once/day. - Postcoital Prophylaxis: Single-dose antibiotic taken after sexual intercourse, if UTIs are temporally related to sexual activity.

- Postmenopausal Women: Antibiotic prophylaxis similar to premenopausal women. Topical estrogen therapy may be beneficial for women with atrophic vaginitis or urethritis to reduce recurrent UTIs.

Summary of Key Management Points:

- Refer infants <3 months with UTI.

- Treat children >3 months with UTI using Amoxicillin/Augmentin, send culture and consider ultrasound.

- Treat non-pregnant women with 3 days of Nitrofurantoin for uncomplicated cystitis.

- Treat asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnant women.

- Consider STI and prostatitis in men with UTI symptoms.

- Do not give prophylaxis for adult with catheter and do not treat asymptomatic bacteriuria in catheterized patients.

Complications of Urinary Tract Infections

While most UTIs are treatable, complications can arise, especially if infections are untreated or complicated.

- Recurrent Infections: Frequent UTIs, defined as two or more in six months or four or more within a year, can be a significant problem, particularly in women.

- Permanent Kidney Damage: Untreated or severe kidney infections (pyelonephritis) can lead to scarring and permanent kidney damage. Chronic kidney infection can also contribute to long-term renal dysfunction.

- Increased Risk in Pregnant Women: UTIs in pregnant women, even asymptomatic bacteriuria, are linked to an increased risk of delivering low birth weight or premature infants.

- Urethral Narrowing (Stricture) in Men: Recurrent urethritis, especially if caused by sexually transmitted infections like gonococcal urethritis, can lead to urethral strictures, causing difficulty with urination.

- Sepsis: This is a potentially life-threatening complication where the infection spreads into the bloodstream and triggers a systemic inflammatory response. Sepsis is more likely if the UTI ascends to the kidneys.

NURSING DIAGNOSIS

Actual Nursing Diagnosis

Impaired Urinary Elimination related to urinary tract infection as evidenced by dysuria, frequency, and lower abdominal discomfort.

Related Factors: Urinary tract infection, inflammation of the bladder and urethra, bacterial irritation of the urinary tract mucosa.

Evidenced By:

- Dysuria (painful urination)

- Urinary frequency

- Urinary urgency

- Lower abdominal discomfort

- Report of burning sensation during urination

- Nocturia

Acute Pain related to urinary tract infection and bladder spasms as evidenced by reports of pelvic pressure, flank pain, and pain rating scale.

Related Factors: Inflammatory process in the urinary tract, bladder spasms secondary to infection, distention of bladder, renal inflammation (in pyelonephritis).

Evidenced By:

- Report of pelvic pressure

- Report of lower abdominal discomfort

- Report of flank pain (if pyelonephritis)

- Pain rating using a pain scale (e.g., 5/10)

- Guarding behavior of abdomen or flank

- Restlessness or irritability

Deficient Knowledge related to prevention and management of urinary tract infections as evidenced by expressed desire for information and questions regarding UTI recurrence.

Related Factors: Lack of prior exposure to information, misinformation, cognitive limitations, information misinterpretation.

Evidenced By:

- Verbalization of lack of understanding about UTI causes, prevention, or management.

- Questions about how to prevent future UTIs.

- Expressed desire for information about UTI.

- Inaccurate follow-through of instructions or procedures related to UTI prevention (if observed).

Fatigue related to physiological effects of infection as evidenced by verbal reports of exhaustion and increased need for rest.

Related Factors: Physiological demands of infection (inflammatory response, immune system activation), pain, disrupted sleep patterns due to nocturia and discomfort.

Evidenced By:

- Verbal report of feeling tired or exhausted.

- Increased need for rest.

- Lethargy or malaise (general feeling of discomfort, illness, or unease).

- Verbalization of feeling weak or lacking energy.

Potential Nursing Diagnoses

Risk for Deficient Fluid Volume related to increased urinary frequency and potential fever.

- Risk Factors: Increased urinary frequency, fever (if present), inadequate fluid intake, vomiting (if pyelonephritis).

Risk for Electrolyte Imbalance related to potential vomiting and altered renal function (especially in pyelonephritis).

- Risk Factors: Vomiting (if pyelonephritis), potential renal involvement in infection, dehydration, pre-existing renal conditions (if applicable).

Risk for Impaired Comfort related to medication side effects (e.g., gastrointestinal upset from antibiotics).

- Risk Factors: Antibiotic therapy, potential for gastrointestinal side effects of antibiotics (nausea, diarrhea), individual sensitivity to medications.

Thanks alot

It’s so so wonderful to read on this platform so try to add some details of nursing process and differential diagnosis.

Notice about nurse patient relationship

Great book it has helped me during my course of study but If I want to download it what can I do

👍🤜

Easy to read And understand

This is so wonderful thank you so much

So educative

So precise and notes easy to understand. I think we shall need more of the rationales of the many investigations and through the management points. Thank u so much.

Thank you man

Nice notes easily understandable.