The muscular-skeletal system is the system that is mainly important in locomotion, body support and makes bodies’ frame work. It consists of skeletal muscles, bones and joints.

Our bodies contain three distinct types of muscle tissue, each uniquely adapted to perform specific roles. While all muscle tissues share the ability to contract, they differ significantly in their location, microscopic appearance (histology), and physiological function.

- Location:

- Attached to bones (or to skin, as in facial muscles).

- Forms the bulk of the body's muscle mass.

- Histology (Microscopic Appearance):

- Striated: Appears striped or banded under a microscope due to the arrangement of contractile proteins (actin and myosin).

- Very long, cylindrical cells (fibers): Can be several centimeters long.

- Multinucleated: Each muscle fiber contains many nuclei, located peripherally (just under the sarcolemma, or cell membrane).

- Voluntary: Contraction is under conscious control.

- Function:

- Movement: Responsible for all voluntary movements of the body (e.g., walking, lifting, speaking, facial expressions).

- Posture: Maintains body posture.

- Stabilize Joints: Helps stabilize joints by exerting tension.

- Heat Generation: Produces heat as a byproduct of contraction, helping to maintain body temperature.

- Location:

- Found exclusively in the wall of the heart (myocardium).

- Histology (Microscopic Appearance):

- Striated: Like skeletal muscle, it also appears striped due to the arrangement of contractile proteins.

- Branched cells: Individual cells are shorter than skeletal muscle fibers and branch, forming an intricate network.

- Uninucleated (or occasionally binucleated): Each cell usually has one (sometimes two) centrally located nuclei.

- Intercalated Discs: Unique to cardiac muscle, these are specialized junctions between adjacent cardiac muscle cells. They contain desmosomes (to prevent cells from pulling apart) and gap junctions (to allow ions to pass quickly, enabling rapid communication and synchronized contraction).

- Involuntary: Contraction is not under conscious control; it's regulated by the heart's intrinsic pacemaker and influenced by the autonomic nervous system.

- Function:

- Pump Blood: Responsible for pumping blood throughout the body, maintaining blood pressure and circulation.

- Location:

- Found in the walls of hollow internal organs (viscera), except the heart.

- Examples: Walls of the digestive tract (stomach, intestines), urinary bladder, respiratory passages (bronchi), arteries, veins, uterus, arrector pili muscles in the skin (causing "goosebumps").

- Histology (Microscopic Appearance):

- Non-striated: Lacks the visible banding pattern seen in skeletal and cardiac muscle because the contractile proteins are arranged more randomly.

- Spindle-shaped cells: Elongated cells with tapered ends.

- Uninucleated: Each cell contains a single, centrally located nucleus.

- Involuntary: Contraction is not under conscious control; it's regulated by the autonomic nervous system, hormones, and local factors.

- Function:

- Peristalsis: Propels substances along internal passageways (e.g., food through the digestive tract).

- Regulation of Organ Volume: Can maintain prolonged contractions, regulating the size of organs (e.g., constricting blood vessels, emptying the bladder).

- Movement of Fluids: Moves fluids and other substances within the body.

- Regulates Airflow: Adjusts the diameter of respiratory passages.

Skeletal muscles are truly fascinating structures, responsible for all voluntary movements, from the subtlest facial expressions to powerful athletic feats. They are unique among muscle types due to their voluntary control and striated appearance.

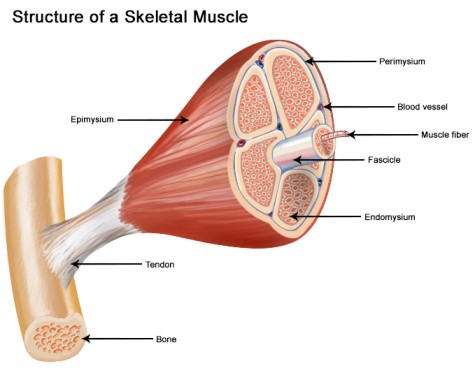

Skeletal muscles are organs composed predominantly of muscle tissue, but they also contain connective tissues, nerves, and blood vessels. They are typically attached to bones, and this attachment is crucial for their function in generating movement.

- Muscle Belly: This is the fleshy, contractile part of the muscle. It contains thousands to hundreds of thousands of individual muscle fibers (cells).

- Attachments to Bones: Skeletal muscles connect to bones, usually at two points:

- Origin: This is typically the less movable (or stationary) attachment point of the muscle. It often lies closer to the trunk or center of the body.

- Insertion: This is the more movable attachment point of the muscle. When the muscle contracts, the insertion point is pulled towards the origin, causing movement at a joint.

- Example: For the biceps brachii muscle in your upper arm:

- Origin: Scapula (shoulder blade)

- Insertion: Radius (forearm bone)

- When the biceps contracts, it pulls the radius towards the scapula, causing the elbow to bend (flex).

- Connective Tissue Attachments: Muscles attach to bones via specialized connective tissues:

- Tendons: These are cord-like bundles of dense regular connective tissue. They are continuous with the connective tissue sheaths within and around the muscle and then with the periosteum (the fibrous membrane covering the bone). This direct continuity ensures that the force generated by muscle contraction is effectively transmitted to the bone, causing movement. Tendons are incredibly strong and relatively inelastic.

- Aponeuroses: These are broad, flat sheets of dense regular connective tissue. They function similarly to tendons, serving as a flat attachment site, especially where muscles are broad and require a wide area of attachment, or where they connect to other muscles. Examples include the aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle in the abdomen, or the plantar aponeurosis in the sole of the foot.

Understanding the hierarchical organization of skeletal muscle is key to appreciating how force is generated and transmitted. It's like a cable, where smaller strands are bundled together to form larger, stronger cables.

- Entire Muscle (Organ Level):

- This is what we commonly recognize as "a muscle" (e.g., biceps brachii, quadriceps femoris).

- It is composed of many bundles of muscle fibers, along with connective tissue, blood vessels, and nerves.

- The entire muscle is typically enclosed by a dense, irregular connective tissue sheath called the epimysium.

- Fascicle (Bundle of Muscle Fibers):

- The entire muscle is divided into numerous smaller bundles called fascicles.

- Each fascicle consists of anywhere from 10 to 100 or more individual muscle fibers.

- Each fascicle is wrapped in its own connective tissue sheath, the perimysium. This compartmentalization allows for independent neural control of different parts of a muscle.

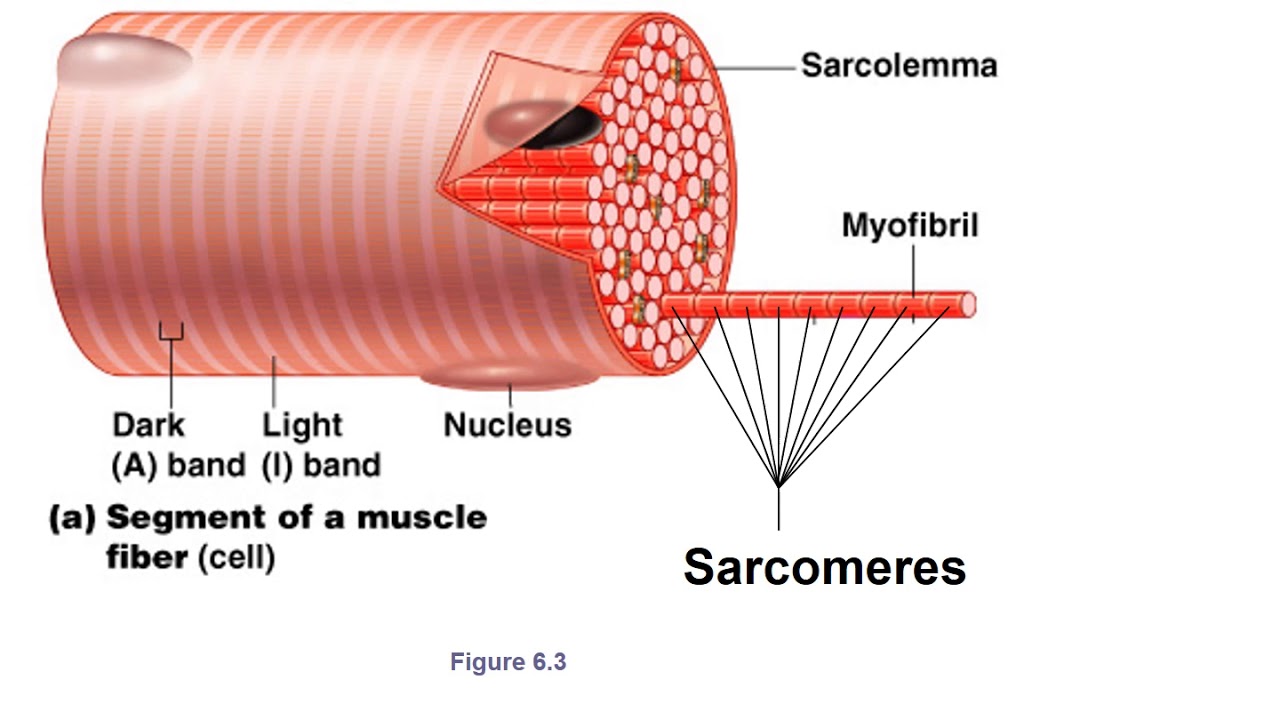

- Muscle Fiber / Muscle Cell (Cellular Level):

- Within each fascicle are the individual muscle cells, which are often referred to as muscle fibers due to their elongated, cylindrical shape.

- These are unique cells: they are very long (can be up to 30 cm in large muscles), multinucleated (containing many nuclei), and are the actual contractile units.

- Each muscle fiber is surrounded by a delicate connective tissue layer called the endomysium.

- The plasma membrane of a muscle fiber is called the sarcolemma, and its cytoplasm is called the sarcoplasm.

- Myofibril:

- Inside each muscle fiber (muscle cell), the sarcoplasm is packed with hundreds to thousands of rod-like structures called myofibrils.

- Myofibrils are the actual contractile elements of the muscle cell. They are composed of even smaller structures called myofilaments.

- The characteristic "striated" or striped appearance of skeletal muscle under a microscope is due to the repeating arrangement of these myofilaments within the myofibrils.

- Myofilaments (Actin & Myosin):

- These are the protein filaments that make up the myofibrils. They are the actual contractile proteins.

- Thick filaments are primarily composed of the protein myosin.

- Thin filaments are primarily composed of the protein actin, along with regulatory proteins troponin and tropomyosin.

- These myofilaments are organized into functional repeating units called sarcomeres.

Entire Muscle ↓ (enclosed by Epimysium) Fascicle (bundle of muscle fibers) ↓ (enclosed by Perimysium) Muscle Fiber / Muscle Cell ↓ (enclosed by Endomysium, plasma membrane is Sarcolemma) Myofibril (contains myofilaments) ↓ Myofilaments (Actin & Myosin) ↓ (organized into) Sarcomere (functional unit)

Skeletal muscles are not just bundles of contractile cells; they are highly organized structures held together and protected by various layers of connective tissue. These sheaths play vital roles in transmitting force, providing pathways for nerves and blood vessels, and maintaining the structural integrity of the muscle.

| Sheath | Location | Tissue Type | Main Function(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Epimysium | Surrounds the entire muscle | Dense Irregular CT | Binds all fascicles, overall protection, forms tendons/aponeuroses, major vessel/nerve pathways |

| Perimysium | Surrounds fascicles (bundles of fibers) | Dense Irregular CT | Divides muscle into fascicles, provides pathways for smaller vessels/nerves |

| Endomysium | Surrounds individual muscle fibers | Areolar (Loose) CT | Electrically insulates fibers, supports capillaries/nerves, transfers force |

These connective tissue layers are continuous with each other and ultimately with the tendons, forming a continuous network that effectively transmits the force generated by the contracting muscle fibers to the bones, enabling movement.

A skeletal muscle fiber, or muscle cell, is a highly specialized and elongated cell designed for contraction. It has several unique features that distinguish it from a typical animal cell.

- Sarcolemma (Plasma Membrane):

- Description: This is the specialized plasma membrane of a muscle fiber. It is a thin, elastic membrane that encloses the sarcoplasm.

- Function:

- Electrical Excitability: It has voltage-gated ion channels that allow it to generate and propagate action potentials (electrical signals).

- Invaginations (T-tubules): At numerous points, the sarcolemma invaginates deep into the muscle fiber to form structures called Transverse Tubules (T-tubules).

- Sarcoplasm (Cytoplasm):

- Description: This is the cytoplasm of a muscle fiber. It contains the usual organelles found in other cells, but also has some specialized components.

- Specialized Components:

- Glycosomes: Granules of stored glycogen, which provide glucose for ATP production.

- Myoglobin: A red pigment that stores oxygen, similar to hemoglobin in blood. Myoglobin efficiently stores oxygen within the muscle cell, providing an oxygen reserve for aerobic respiration during periods of high activity.

- Mitochondria: Numerous mitochondria are packed between the myofibrils, reflecting the high energy demand of muscle contraction (producing ATP).

- Myofibrils: The most prominent component, myofibrils are rod-like contractile elements that make up about 80% of the muscle fiber volume.

- Sarcoplasmic Reticulum (SR) (Endoplasmic Reticulum):

- Description: This is a highly specialized, elaborate network of smooth endoplasmic reticulum that surrounds each myofibril like a loosely woven sleeve. It runs longitudinally along the myofibril. At the A-I band junction, it forms larger, perpendicular channels called terminal cisternae.

- Function:

- Calcium Storage and Release: The primary function of the SR is to store and regulate the intracellular concentration of calcium ions (Ca2+). It contains a high concentration of Ca2+ pumps that actively transport Ca2+ from the sarcoplasm into the SR, and Ca2+ release channels that open in response to electrical signals.

- Excitation-Contraction Coupling: The release of Ca2+ from the SR is the critical step that initiates muscle contraction.

- T-Tubules (Transverse Tubules):

- Description: These are deep, invaginations (inward extensions) of the sarcolemma that run perpendicular to the long axis of the muscle fiber. They are located at the A-I band junction of each sarcomere.

- Function:

- Rapid Impulse Transmission: T-tubules act as rapid communication channels, allowing the electrical impulse (action potential) generated on the sarcolemma to quickly penetrate deep into the muscle fiber, reaching every sarcomere.

- Coupling with SR: Each T-tubule runs between two terminal cisternae of the SR, forming a structure called a triad. This close anatomical arrangement is crucial for excitation-contraction coupling, as the electrical signal in the T-tubule directly triggers Ca2+ release from the adjacent SR terminal cisternae.

- Nuclei (Multinucleated):

- Description: Unlike most cells, skeletal muscle fibers are multinucleated, meaning they contain many nuclei. These nuclei are typically located just beneath the sarcolemma (peripherally).

- Function: Protein Synthesis: The large number of nuclei allows for the efficient production of the vast amounts of proteins (especially contractile proteins like actin and myosin) needed for the maintenance and repair of the very long muscle fiber, as well as for muscle growth (hypertrophy).

Myofibrils are the long, cylindrical, contractile organelles found within the sarcoplasm of a muscle fiber. It's their precise arrangement of protein filaments that gives skeletal muscle its characteristic striated appearance and enables contraction.

- Myofibrils and Sarcomeres:

- Each myofibril is composed of a chain of repeating contractile units called sarcomeres.

- A sarcomere is the fundamental functional unit of a skeletal muscle, extending from one Z disc to the next Z disc. It is the smallest unit of a muscle fiber that can contract.

- The precise arrangement of two types of myofilaments within each sarcomere creates the striations.

- Myofilaments:

- Thick Filaments (Myosin Filaments): Composed primarily of the protein myosin. Each myosin molecule has a "rod-like" tail and two globular "heads." The heads are crucial for muscle contraction, as they bind to actin and possess ATPase activity. They are found in the center of the sarcomere and do not extend the entire length of the sarcomere.

- Thin Filaments (Actin Filaments): Composed primarily of the protein actin, which forms a double helix. Also contains two regulatory proteins:

- Tropomyosin: A rod-shaped protein that spirals around the actin core, blocking the myosin-binding sites on actin in a relaxed muscle.

- Troponin: A three-polypeptide complex that binds to actin, tropomyosin, and calcium ions (Ca2+). Its binding of Ca2+ causes a conformational change that moves tropomyosin away from the myosin-binding sites.

- Bands and Zones within a Sarcomere: The alternating dark and light bands give skeletal muscle its striated appearance.

- Z Disc (Z Line): A coin-shaped sheet of proteins (primarily alpha-actinin) that anchors the thin filaments and connects myofibrils to one another. It defines the lateral boundaries of a single sarcomere.

- I Band (Light Band): A lighter region on either side of the Z disc. Contains only thin filaments (actin). During contraction, the I band shortens.

- A Band (Dark Band): A darker, central region of the sarcomere. Contains the entire length of the thick filaments (myosin). Also contains the inner ends of the thin filaments that overlap with the thick filaments. The A band's length does not change significantly during contraction.

- H Zone (H Band): A lighter region within the center of the A band. Contains only thick filaments (myosin); there is no overlap with thin filaments in a relaxed muscle. During contraction, the H zone shortens and can even disappear as thin filaments slide past.

- M Line: A dark line in the exact center of the H zone (and thus the A band). Consists of proteins (e.g., myomesin) that anchor the thick filaments in place and keep them aligned.

During muscle contraction, the thin filaments slide past the thick filaments, pulling the Z discs closer together. This causes the sarcomere to shorten, and the I bands and H zones to narrow or disappear, while the A band's length remains relatively constant. This mechanism is known as the Sliding Filament Model of Contraction.

The Sliding Filament Model is the universally accepted explanation for how skeletal muscles contract. It states that during contraction, the thin filaments (actin) slide past the thick filaments (myosin), causing the sarcomere to shorten. The myofilaments themselves do not shorten; rather, their overlap increases.

Here's a breakdown of the key principles:

- Relaxed State:

- In a relaxed muscle fiber, the thick and thin filaments overlap only slightly at the ends of the A band.

- The H zone (containing only thick filaments) and the I band (containing only thin filaments) are at their maximum width.

- The myosin heads are "cocked" and energized, but they are prevented from binding to actin by the regulatory protein tropomyosin, which covers the myosin-binding sites on the actin molecules.

- Initiation of Contraction (The Signal):

- A nerve impulse (action potential) arrives at the neuromuscular junction (which we'll detail later).

- This electrical signal is transmitted down the sarcolemma and into the T-tubules.

- The signal in the T-tubules triggers the release of calcium ions (Ca2+) from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) into the sarcoplasm.

- Role of Calcium (Ca2+) and Regulatory Proteins:

- When Ca2+ is released into the sarcoplasm, it binds to the regulatory protein troponin.

- Binding of Ca2+ causes troponin to change shape.

- This shape change in troponin, in turn, pulls the tropomyosin molecule away from the active (myosin-binding) sites on the actin filament.

- With the binding sites now exposed, the myosin heads are free to attach to actin.

- Cross-Bridge Formation (Myosin-Actin Binding):

- The energized myosin heads (which have already hydrolyzed ATP into ADP and inorganic phosphate, storing the energy) bind to the exposed active sites on the actin filament, forming cross-bridges.

- The Power Stroke:

- Once the myosin head is attached to actin, the stored energy is released, causing the myosin head to pivot or "bend." This bending motion is called the power stroke.

- The power stroke pulls the thin filament (actin) toward the M line (the center of the sarcomere).

- As the myosin head pivots, it releases ADP and inorganic phosphate.

- Cross-Bridge Detachment:

- A new ATP molecule then binds to the myosin head.

- The binding of ATP causes the myosin head to detach from the actin filament. This detachment is crucial; without new ATP, the cross-bridges would remain attached, leading to a state known as rigor mortis (stiffening after death due to lack of ATP).

- Cocking of the Myosin Head:

- The newly bound ATP is immediately hydrolyzed (broken down) by the ATPase enzyme on the myosin head into ADP and inorganic phosphate (Pi).

- This hydrolysis provides the energy to "re-cock" or re-energize the myosin head, returning it to its high-energy, ready-to-bind position.

- Repetition of the Cycle:

- As long as Ca2+ is present and bound to troponin (keeping the actin binding sites exposed) and sufficient ATP is available, the cycle of cross-bridge formation, power stroke, and detachment will repeat multiple times.

- Each cycle pulls the thin filament a little further toward the M line.

- Sarcomere Shortening:

- With each power stroke, the thin filaments slide further inward.

- This sliding action shortens the sarcomere (the distance between Z discs).

- As all the sarcomeres in a myofibril shorten simultaneously, the entire myofibril shortens, which in turn causes the entire muscle fiber and ultimately the entire muscle to shorten, generating force and producing movement.

- Z discs: Move closer together.

- I bands: Shorten (may disappear in maximal contraction).

- H zone: Shortens (may disappear in maximal contraction).

- A band: Remains the same length (myosin filaments don't shorten).

These four proteins are the molecular machinery that directly drives and regulates muscle contraction.

- Actin (Thin Filament Component):

- Structure: Actin forms the "backbone" of the thin filaments. It's a globular protein (G-actin) that polymerizes to form long, fibrous strands (F-actin), which then twist together into a double helix.

- Role in Contraction: Actin contains the active (myosin-binding) sites. It is the protein that the myosin heads attach to and pull on during the power stroke. Actin essentially provides the "track" along which myosin travels.

- Key Action: Binds to myosin heads to form cross-bridges.

- Myosin (Thick Filament Component):

- Structure: Myosin is a large motor protein that makes up the thick filaments. Each myosin molecule has a long tail and two globular heads. The heads contain an actin-binding site and an ATPase (enzyme that breaks down ATP) site.

- Role in Contraction: Myosin is the "motor" protein. Its heads bind to actin, pivot (power stroke) to pull the actin filament, and then detach. The ATPase activity in the heads hydrolyzes ATP, providing the energy for these movements.

- Key Action: Forms cross-bridges with actin, pulls actin filaments, hydrolyzes ATP for energy.

- Tropomyosin (Regulatory Protein of Thin Filament):

- Structure: A rod-shaped protein that spirals around the actin filament, covering the active (myosin-binding) sites on the actin molecules in a relaxed muscle.

- Role in Contraction: Its primary role is to block the myosin-binding sites on actin in a relaxed muscle. This prevents myosin from binding to actin and initiating contraction when the muscle is not stimulated.

- Key Action: Blocks actin's active sites, preventing contraction in the absence of calcium.

- Troponin (Regulatory Protein of Thin Filament):

- Structure: A complex of three globular polypeptides, each with a specific function:

- TnI (inhibitory): Binds to actin, holding the troponin-tropomyosin complex in place.

- TnT (tropomyosin-binding): Binds to tropomyosin, helping to position it on the actin filament.

- TnC (calcium-binding): Binds to calcium ions (Ca2+).

- Role in Contraction: Troponin is the calcium sensor that initiates the unblocking of actin. When calcium ions become available (released from the sarcoplasmic reticulum), they bind to the TnC subunit. This binding causes a conformational change in troponin, which then pulls tropomyosin away from the myosin-binding sites on actin.

- Key Action: Binds calcium, causing tropomyosin to move off the actin binding sites, thereby allowing myosin to bind.

- Structure: A complex of three globular polypeptides, each with a specific function:

- Relaxed: Tropomyosin (held by troponin) blocks actin's binding sites. Myosin cannot bind.

- Stimulated (Ca2+ present): Ca2+ binds to troponin. Troponin changes shape, pulling tropomyosin away from actin's binding sites.

- Contraction: Myosin heads bind to exposed actin sites, perform the power stroke, and pull the actin filament.

- Relaxation (Ca2+ removed): Ca2+ detaches from troponin. Troponin returns to its original shape, allowing tropomyosin to once again cover the actin binding sites. Myosin detaches, and the muscle relaxes.

The neuromuscular junction (NMJ) is the specialized synapse where a motor neuron communicates with a skeletal muscle fiber. It's the critical link that translates a nerve impulse into a muscle action potential.

Here's the sequence of events at the NMJ:

- Action Potential Arrives at the Axon Terminal: A nerve impulse, or action potential (AP), travels down the motor neuron axon and reaches the axon terminal (also called the synaptic knob or terminal bouton), which is the enlarged end of the motor neuron.

- Voltage-Gated Calcium Channels Open:

- The arrival of the action potential at the axon terminal depolarizes the membrane, opening voltage-gated calcium (Ca2+) channels in the presynaptic membrane (the membrane of the axon terminal).

- Ca2+ ions, which are in higher concentration outside the cell, rush into the axon terminal.

- Acetylcholine (ACh) Release:

- The influx of Ca2+ into the axon terminal triggers the fusion of synaptic vesicles (which contain the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, ACh) with the presynaptic membrane.

- Acetylcholine (ACh) is then released into the synaptic cleft (the tiny space between the axon terminal and the muscle fiber). This release occurs via exocytosis.

- ACh Binds to Receptors on the Motor End Plate:

- ACh diffuses across the synaptic cleft and binds to specific nicotinic acetylcholine receptors located on the motor end plate of the muscle fiber. The motor end plate is a specialized region of the sarcolemma that is highly folded to increase surface area and contains a high density of these receptors.

- These receptors are ligand-gated ion channels.

- Ion Channels Open and Local Depolarization (End Plate Potential):

- The binding of ACh to its receptors causes the ligand-gated ion channels to open.

- These channels allow both sodium ions (Na+) to flow into the muscle fiber and potassium ions (K+) to flow out.

- However, more Na+ enters than K+ leaves, resulting in a net influx of positive charge. This causes a local depolarization of the motor end plate, called an end plate potential (EPP).

- Generation of Muscle Action Potential:

- If the end plate potential reaches a critical threshold, it triggers the opening of voltage-gated sodium channels in the adjacent sarcolemma (the sarcolemma immediately outside the motor end plate).

- A rapid influx of Na+ through these voltage-gated channels generates a full-blown muscle action potential.

- This action potential then propagates (travels) along the entire sarcolemma and deep into the muscle fiber via the T-tubules.

- Termination of ACh Activity:

- To prevent continuous muscle contraction, the effects of ACh must be rapidly terminated. This is achieved by the enzyme acetylcholinesterase (AChE), which is located in the synaptic cleft and on the sarcolemma.

- AChE breaks down ACh into its components (acetic acid and choline), rendering it inactive.

- This rapid degradation ensures that each nerve impulse produces only one muscle action potential.

Nerve AP ➔ Ca2+ Influx into Axon Terminal ➔ ACh Release ➔ ACh Binds to Receptors on Motor End Plate ➔ Ligand-gated Channels Open (Na+ Influx > K+ Efflux) ➔ End Plate Potential ➔ Voltage-gated Na+ Channels Open (if threshold reached) ➔ Muscle Action Potential ➔ ACh broken down by AChE.

This sequence ensures precise and controlled communication between the nervous system and the musculoskeletal system.

The skeletal system, comprised of bones, cartilage, ligaments, and other connective tissues, is far more than just a rigid framework. It's a dynamic and vital organ system with several critical functions.

- Support:

- Description: The skeletal system provides a rigid framework that supports the body's soft tissues and organs. It acts as the internal scaffolding that holds the body upright and maintains its overall shape.

- Example: Our legs and vertebral column support the weight of the trunk, and the rib cage supports the thoracic wall.

- Protection:

- Description: Bones form protective enclosures for many of the body's vital organs, shielding them from external forces and trauma.

- Example: The skull protects the brain, the vertebral column protects the spinal cord, and the rib cage protects the heart and lungs.

- Movement:

- Description: Bones serve as levers for muscles. When muscles contract, they pull on bones, causing movement at the joints. The joints themselves act as fulcrums for these levers.

- Example: The biceps muscle contracts to pull on the forearm bones (radius and ulna), causing the arm to flex at the elbow. Without bones, muscles would have nothing firm to pull against.

- Mineral Storage:

- Description: Bone tissue acts as a reservoir for several important minerals, most notably calcium and phosphate. These minerals are essential for numerous physiological processes, including nerve impulse transmission, muscle contraction, blood clotting, and ATP production.

- Example: When blood calcium levels drop, calcium can be withdrawn from the bones to restore homeostasis. Conversely, excess calcium can be stored in the bones. This dynamic storage helps maintain mineral balance in the blood.

- Hematopoiesis (Blood Cell Formation):

- Description: Inside certain bones, primarily in the red bone marrow, the process of hematopoiesis occurs. This is the production of all blood cells, including red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets.

- Example: In adults, red bone marrow is found in the flat bones (like the sternum, ribs, and hip bones) and the epiphyses of long bones (like the femur and humerus).

Bones come in a variety of shapes and sizes, and their classification by shape often reflects their primary function. There are five main categories:

- Long Bones:

- Description: Characterized by being significantly longer than they are wide. They typically have a shaft (diaphysis) and two expanded ends (epiphyses). They are primarily compact bone with some spongy bone at the ends.

- Function: Act as levers to aid in movement and support the body's weight.

- Examples: Femur (thigh bone), Humerus (upper arm bone), Tibia and Fibula (lower leg bones), Radius and Ulna (forearm bones), Phalanges (finger and toe bones).

- Short Bones:

- Description: Roughly cube-shaped, with their length, width, and height being approximately equal. They primarily consist of spongy bone surrounded by a thin layer of compact bone.

- Function: Provide stability and some movement, often articulating with multiple other bones.

- Examples: Carpals (wrist bones), Tarsals (ankle bones).

- Flat Bones:

- Description: Thin, flattened, and often curved. They are typically composed of two parallel plates of compact bone, with a layer of spongy bone (diploe) sandwiched between them.

- Function: Provide broad surfaces for muscle attachment and often protect underlying soft organs.

- Examples: Cranial Bones (skull bones, e.g., frontal, parietal), Sternum (breastbone), Scapulae (shoulder blades), Ribs.

- Irregular Bones:

- Description: Have complicated, unique shapes that do not fit into the other categories. Their structure is typically a mix of compact and spongy bone.

- Function: Serve various specialized roles, including protection, support, and providing attachment points for muscles.

- Examples: Vertebrae (spinal bones), Pelvic Bones (hip bones, e.g., ilium, ischium, pubis), Facial Bones (e.g., sphenoid, ethmoid).

- Sesamoid Bones:

- Description: Small, round, or oval bones that are embedded within tendons, often found at joints. They vary in number among individuals.

- Function: Act to protect tendons from excessive wear and tear, and can alter the angle of muscle pull, increasing the mechanical advantage of the muscle.

- Examples: Patella (kneecap) - the largest sesamoid bone. Small sesamoid bones are often found in the tendons of the thumb and big toe.

Long bones, like the femur or humerus, are exemplary for studying bone anatomy due to their distinct and easily identifiable regions.

- Diaphysis (Shaft):

- Description: This is the main, elongated cylindrical shaft of a long bone. It forms the long axis of the bone.

- Composition: Primarily composed of a thick collar of compact bone that surrounds the medullary cavity.

- Function: Provides strength and structural support, withstands stresses along the longitudinal axis of the bone.

- Epiphyses (Bone Ends):

- Description: These are the expanded, knob-like ends of a long bone, located at both proximal and distal extremities.

- Composition: The exterior consists of a thin layer of compact bone, while the interior is filled with spongy (cancellous) bone.

- Function: Articulate with other bones to form joints; provide an increased surface area for joint stability and muscle attachment.

- Metaphyses (Growth Plate Region in growing bone):

- Description: This is the region where the diaphysis joins the epiphysis. In a growing bone, this area contains the epiphyseal plate (growth plate), a layer of hyaline cartilage where longitudinal bone growth occurs.

- Composition: Primarily cartilage in growing bones; in adults, after growth has stopped, the epiphyseal plate ossifies and becomes the epiphyseal line, a remnant of the growth plate.

- Function: Site of longitudinal bone growth during childhood and adolescence.

- Articular Cartilage:

- Description: A thin layer of hyaline cartilage that covers the articular (joint) surfaces of the epiphyses.

- Composition: Hyaline cartilage, a smooth, slippery tissue.

- Function: Reduces friction and absorbs shock at movable joints, allowing for smooth movement between bones. It lacks a perichondrium and is avascular (receives nutrients from synovial fluid).

- Periosteum:

- Description: A tough, fibrous membrane that covers the outer surface of the entire bone, except where articular cartilage is present. It is richly supplied with blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, and nerves.

- Composition:

- Outer fibrous layer: Dense irregular connective tissue, providing protection and attachment for tendons and ligaments.

- Inner osteogenic layer: Contains osteoprogenitor cells (bone stem cells), osteoblasts (bone-forming cells), and osteoclasts (bone-resorbing cells).

- Function: Protects the bone. Serves as an attachment point for tendons and ligaments. Plays a crucial role in bone growth in width (appositional growth) and in bone repair. Contains nerve fibers, which makes bone pain very acute.

- Endosteum:

- Description: A delicate connective tissue membrane that lines the inner surfaces of the medullary cavity, covering the trabeculae of spongy bone and lining the canals that pass through compact bone.

- Composition: Contains osteoprogenitor cells, osteoblasts, and osteoclasts.

- Function: Involved in bone growth, repair, and remodeling.

- Medullary Cavity (Marrow Cavity):

- Description: The hollow central cavity within the diaphysis of long bones.

- Composition: In adults, it contains yellow bone marrow, which is primarily adipose (fat) tissue, serving as an energy reserve. In infants and children, and in some adult bones (like the sternum and hip bones), it contains red bone marrow, which is the primary site of hematopoiesis (blood cell formation).

- Function: Stores bone marrow.

All bones are made of both compact and spongy bone, but their relative proportions and arrangements differ depending on the bone's shape and function.

| Feature | Compact Bone | Spongy Bone |

|---|---|---|

| Appearance | Dense, solid, smooth | Porous, network-like, trabecular |

| Structural Unit | Osteon (Haversian System) | Trabeculae (no osteons) |

| Location | Outer layer of all bones; diaphysis of long bones | Interior of bones; epiphyses of long bones |

| Marrow | Medullary cavity (in diaphysis) | Spaces between trabeculae |

| Weight | Heavier | Lighter |

| Function | Strength, protection, withstands stress | Lightness, marrow storage, stress distribution |

The microscopic structure of compact bone is highly organized around its fundamental unit: the osteon.

- Osteon (Haversian System): The primary structural and functional unit of compact bone. It is an elongated cylinder oriented parallel to the long axis of the bone, acting like a tiny weight-bearing pillar.

- Central Canal (Haversian Canal): Runs through the core of each osteon. Contains blood vessels (arterioles and venules), nerve fibers, and lymphatic vessels that supply nutrients to and remove waste from the bone cells.

- Lamellae: Concentric rings (like growth rings on a tree trunk) of bone matrix that surround the central canal.

- Concentric Lamellae: Form the main bulk of the osteon.

- Interstitial Lamellae: Found between intact osteons.

- Circumferential Lamellae: Extend around the entire circumference of the diaphysis.

- Lacunae: Small, hollow spaces or cavities located at the junctions between the lamellae. Each lacuna houses a single mature bone cell called an osteocyte.

- Canaliculi: Tiny, hair-like canals that radiate out from the lacunae, connecting them to each other and to the central canal. They allow osteocytes to communicate and facilitate transport of nutrients.

- Osteocytes: Mature bone cells, derived from osteoblasts, that reside in the lacunae. They maintain the bone matrix and act as stress sensors.

- Osteoblasts: Bone-forming cells found on the surface of bone tissue. They synthesize and secrete the organic components of the bone matrix (osteoid).

- Osteoclasts: Large, multinucleated cells found on bone surfaces. They resorb (break down) bone matrix by secreting acids and enzymes.

- Primary Substance: Osteoid – the unmineralized organic part of the matrix.

- Composition:

- Collagen fibers (Type I): Provide flexibility and tensile strength (resist stretching).

- Ground substance: A gel-like material contributing to resilience.

- Contribution to Bone Properties: Flexibility and Tensile Strength.

- Primary Substance: Mineral salts, primarily calcium phosphates.

- Composition:

- Hydroxyapatite: Calcium phosphate crystals that are extremely hard and dense.

- Other mineral salts: Calcium carbonate, magnesium phosphate, etc.

- Contribution to Bone Properties: Hardness and Compressional Strength (resist squeezing).

Think of reinforced concrete:

- The steel rebar provides the tensile strength and flexibility (like collagen fibers).

- The concrete provides the compressional strength and hardness (like hydroxyapatite crystals).

Ossification (osteogenesis) is the process of bone tissue formation.

| Feature | Intramembranous Ossification | Endochondral Ossification |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Structure | Fibrous connective tissue membrane | Hyaline cartilage model |

| Bones Formed | Flat bones of skull, mandible, clavicles | Most other bones (long, short, irregular bones) |

| Mechanism | Bone forms directly from mesenchymal tissue | Cartilage model is replaced by bone tissue |

| Growth Plates | Not directly involved | Involves epiphyseal plates for longitudinal growth |

Bone remodeling is a lifelong process involving bone resorption (removal) and bone formation. It occurs in packets called basic multicellular units (BMUs).

- Resorption Phase (Osteoclast Activity): Osteoclasts migrate to the bone surface, create a sealed compartment, and secrete lysosomal enzymes and hydrochloric acid to dissolve the bone matrix.

- Reversal Phase: Osteoclasts undergo apoptosis or detach. Macrophages clean up debris.

- Formation Phase (Osteoblast Activity): Osteoblasts arrive, secrete osteoid, and mineralization occurs. Osteoblasts become trapped and differentiate into osteocytes.

| Hormone | Source | Stimulus for Release | Effect on Bone | Overall Effect on Blood Calcium |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTH | Parathyroid Glands | Low blood Ca²⁺ | Stimulates osteoclast activity | Increases |

| Calcitonin | Thyroid Gland (C cells) | High blood Ca²⁺ | Inhibits osteoclast activity | Decreases |

- Hematoma Formation (Immediate - Days 1-5): Blood vessels rupture, forming a clot (hematoma). Inflammation initiates.

- Fibrocartilaginous Callus Formation (Days 3-21): New capillaries grow. Fibroblasts and chondroblasts create a soft callus of collagen and cartilage to bridge bone ends.

- Bony Callus Formation (Weeks 3-4): Osteoblasts convert the soft callus into a hard, bony callus (spongy bone).

- Bone Remodeling (Months to Years): Excess material is removed by osteoclasts. Compact bone is laid down to restore the original shape and strength.

Joints are the sites where two or more bones meet. They bind bones together and allow mobility.

- Bones joined by dense fibrous connective tissue. No joint cavity.

- Most are immovable (synarthrotic).

- Subtypes: Sutures (skull), Syndesmoses (tibia/fibula), Gomphoses (teeth).

- Bones united by cartilage. No joint cavity.

- Allow limited movement (amphiarthrotic) or are immovable.

- Subtypes: Synchondroses (epiphyseal plates), Symphyses (pubic symphysis).

- Bones separated by a fluid-filled joint cavity.

- All are freely movable (diarthrotic).

- Examples: Shoulder, elbow, hip, knee.

- Articular Cartilage: Hyaline cartilage covers bone ends. Reduces friction, absorbs shock.

- Joint (Synovial) Cavity: Potential space filled with synovial fluid.

- Articular Capsule: Double-layered (Outer fibrous layer, Inner synovial membrane).

- Synovial Fluid: Viscous fluid for lubrication, nutrient distribution, and shock absorption.

- Reinforcing Ligaments: Connect bone to bone, providing stability.

- Nerves and Blood Vessels: Detect pain/position and supply nutrients.

Additional Structures: Articular Discs (Menisci), Bursae, and Tendon Sheaths.

- Gliding (Translational): Flat surfaces slip over one another (e.g., wrist bones).

- Angular: Flexion, Extension, Hyperextension, Abduction, Adduction, Circumduction.

- Rotation: Turning of a bone around its own long axis.

- Special Movements: Supination/Pronation, Dorsiflexion/Plantar Flexion, Inversion/Eversion, Protraction/Retraction, Elevation/Depression, Opposition.

| Joint Type | Articulating Surfaces | Movement Type | Axes | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plane | Flat/slightly curved | Gliding | Nonaxial | Intercarpal, vertebral facets |

| Hinge | Cylinder in trough | Flexion/Extension | Uniaxial | Elbow, knee, fingers |

| Pivot | Rounded in ring | Rotation | Uniaxial | Proximal radioulnar, atlantoaxial |

| Condylar | Oval condyle in depression | Flexion/Ext, Abd/Add | Biaxial | Wrist, knuckles |

| Saddle | Saddle-shaped | Flexion/Ext, Abd/Add | Biaxial | Carpometacarpal of thumb |

| Ball-and-Socket | Spherical head in cup | Universal movement | Multiaxial | Shoulder, hip |

- Arthritis:

- Osteoarthritis (OA): Wear-and-tear, degenerative. Breakdown of articular cartilage.

- Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA): Autoimmune. Immune system attacks synovial membranes.

- Gouty Arthritis (Gout): Uric acid crystals deposit in joints.

- Bursitis: Inflammation of a bursa.

- Tendonitis: Inflammation of a tendon.

- Sprains: Ligaments stretched or torn.

- Dislocations: Bones forced out of alignment.

- Description: Genetic diseases characterized by progressive weakness and degeneration of skeletal muscles due to lack of specific proteins (like dystrophin).

- Types:

- Duchenne (DMD): Severe, early onset, primarily affects males.

- Becker (BMD): Milder, later onset.

- Description: Autoimmune disease characterized by fluctuating muscle weakness and fatigue.

- Pathophysiology: Antibodies attack acetylcholine receptors at the NMJ.

- Symptoms: Drooping eyelids, double vision, difficulty swallowing.

- Description: Chronic disorder characterized by widespread musculoskeletal pain, fatigue, and sleep issues.

- Causes: Dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, fatigue, nerve compression.

- Definition: Injury to a muscle or tendon (overstretched or torn).

- Grading: Mild, Moderate, Severe (rupture).

- Description: Rapid breakdown of damaged skeletal muscle tissue releasing myoglobin into the bloodstream.

- Clinical Implication: Myoglobin is toxic to kidneys, leading to acute kidney injury.

- Description: Painful condition caused by pressure buildup within a confined muscle compartment.

- Intervention: Fasciotomy (surgical emergency) to relieve pressure.

DISEASES AFFECTING SKELETAL MUSCLES

MYASTHENIA GRAVIS

This is another autoimmune disease predominantly affecting females. There is un usual fatigue due to lack of acetylcholine receptor at the myoneural junctions which impair muscle contraction.

Signs and symptoms

- The onset is gradual.

- Excessive fatigue particularly towards end of the day with drooping of eye lids

- Frequent falls

- Difficult in chewing and swallowing

- Involvement of respiratory muscles may lead to respiratory failure

- A weak cough reflex may lead to accumulation of secretions and infections

Treatment and management

- Short acting anticholine esterase drugs like edrophonium

- Long acting ant cholinesterase drugs e.g. neostigmine or pyrisostigmine

- Thymectomy and steroids also provide relief.

- Exercises

MYOSITIS (MYOPATHY)

Myositis or myopathy refers to a group of primary diseases of muscles; Myositis (inflammation of muscles) can be genetically diseases.

Progressive muscular atrophy is a group of hereditary disorder characterized by progressive delegation of muscles without involvement of bones.

The wasting and weakness of muscles is symmetrically without any sensory loss. The affected muscles are large, firm but weak.

The child walks with a waddling giant like that of the duck

When rising from a supine lying position, in bed, the child rolls on his face (prone position) and then uses his arms to push his body up (tripod sign). Death in second decade is usual due to involvement of respiratory muscles.

Fibrositis – rheumatism (fibrocystic)

Fibrositis and muscular Rheumatism are terms used to describe recurring pains, stiffness in the muscles or the back, various parts of the body being involved from time to time.

The disease does not progress and such vague symptoms are attributable to emotional stress.

Treatment

Is usually symptomatic, heat and massages may be helpful and aspirin or one of the NSAIDS can be prescribed.