Table of Contents

ToggleBRONCHITIS

Introduction

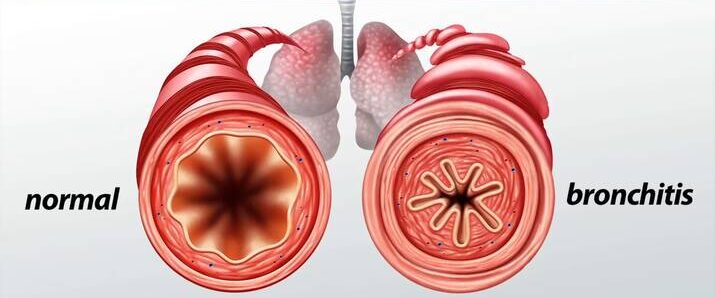

Bronchitis is a common respiratory condition characterized by an inflammation of the mucous membranes lining the bronchi. These are the larger and medium-sized airways that serve as critical conduits for airflow, transporting air from the trachea (windpipe) into the more distal and delicate lung parenchyma, where gas exchange occurs. This inflammation leads to a cascade of physiological changes, including swelling, increased mucus production, and irritation of the airways, which collectively impair normal respiratory function.

Types of Bronchitis

Bronchitis is broadly classified based on its duration and clinical presentation into two main categories: acute and chronic.

- Acute Bronchitis:

This form of bronchitis represents a transient inflammation of the large airways of the lung, typically characterized by a sudden and rapid onset of symptoms. It is usually self-limiting, meaning it resolves spontaneously, often within a period of 10 days to 3 weeks, although the associated cough can sometimes persist for several weeks longer. Acute bronchitis is commonly a sequela of an upper respiratory tract infection.

- Chronic Bronchitis:

In contrast, chronic bronchitis is defined by a persistent and recurrent inflammation of the large airways of the lung. Its development is often gradual, and the defining characteristic is a chronic productive cough that lasts for at least 3 months in a year for two consecutive years, in the absence of other underlying lung diseases that could explain the cough. This condition is often a component of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) and is typically associated with long-term exposure to irritants, most notably cigarette smoke.

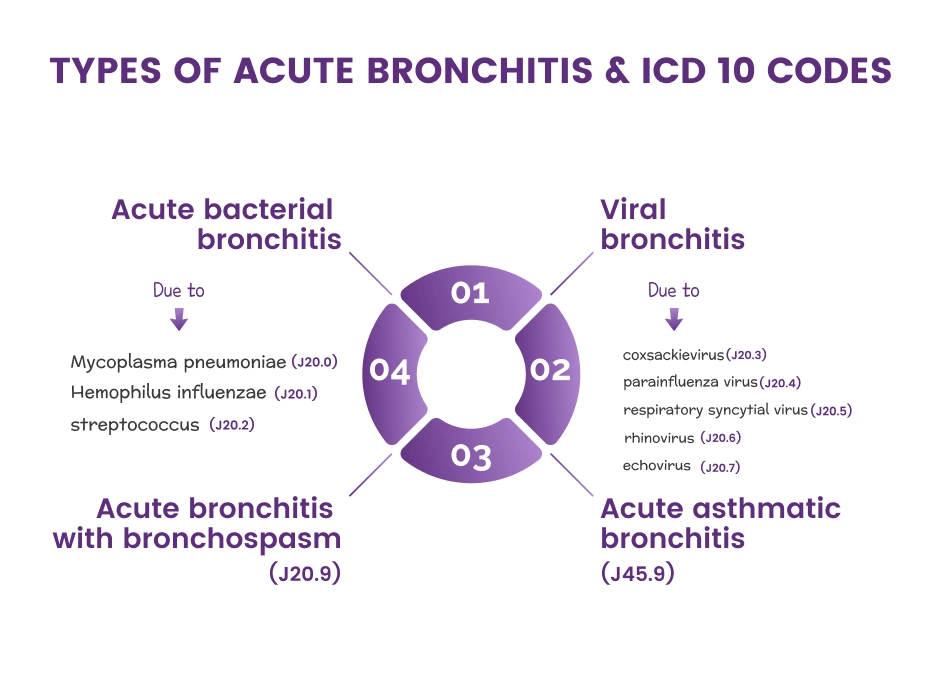

Classification of bronchitis according to cause

Beyond duration, bronchitis can also be classified based on its etiology, distinguishing between infectious and non-infectious triggers.

1. Infectious/Contagious Bronchitis:This type of bronchitis occurs when the inflammation of the bronchi is caused by a living biological agent, or pathogen. These pathogens are transmitted from person to person or from the environment. Common infectious causes include:

- Viral Bronchitis: By far the most common cause, accounting for approximately 90-95% of acute bronchitis cases in healthy adults. Viruses such as Influenza A and B, Parainfluenza, Adenovirus, Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV), Rhinovirus, and Coronavirus are frequent culprits.

- Bacterial Bronchitis: Less common in acute settings, but can occur, often as a secondary infection following a viral illness. Common bacterial agents include Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydophila pneumoniae, Bordetella pertussis (whooping cough), Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Haemophilus influenzae. Bacterial bronchitis may also be seen in chronic bronchitis exacerbations.

- Fungal Bronchitis: Rarer, typically affecting individuals with compromised immune systems (e.g., those with HIV/AIDS, organ transplant recipients, or those on immunosuppressive therapy). Examples include Aspergillus species or Candida species.

This form of bronchitis is not caused by a pathogen and therefore is not transmissible. Instead, it results from exposure to various irritants or other underlying conditions. Common non-infectious causes include:

- Chemical Irritants: Inhalation of toxic fumes, industrial pollutants, strong chemicals (e.g., ammonia, chlorine, sulfur dioxide), or particulate matter can directly irritate and inflame the bronchial lining.

- Environmental Factors: Exposure to high levels of air pollution, smog, dust, or allergens (e.g., pollen, pet dander, mold spores) can trigger an inflammatory response in the airways.

- Allergic Reactions: In susceptible individuals, exposure to specific allergens can induce an allergic bronchial inflammation, sometimes referred to as allergic bronchitis.

- Gastric Reflux: Chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) can lead to micro-aspiration of stomach acid into the airways, causing irritation and inflammation, particularly contributing to chronic cough and sometimes chronic bronchitis.

- Drug Side Effects: Certain medications, though less common, can rarely induce a form of bronchitis as a side effect.

- Mechanical Irritation: Prolonged exposure to very cold or very dry air can sometimes cause irritation, particularly in sensitive airways.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiological processes underlying acute and chronic bronchitis differ significantly, reflecting their distinct etiologies and clinical courses.

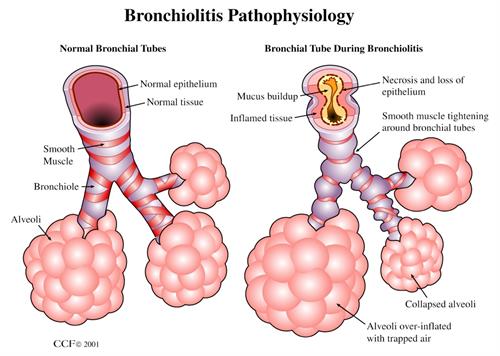

Acute Bronchitis

Acute bronchitis is fundamentally the result of acute inflammation of the bronchi, triggered predominantly by various factors, with viral infections being the most common. Other triggers can include bacterial infections, allergens, environmental pollutants, or even aspiration. The inflammatory process unfolds as follows:

- Initial Irritation and Viral Entry: Typically, a viral upper respiratory infection (URI) precedes acute bronchitis. Viruses replicate in the epithelial cells lining the upper airways and can then spread downwards to the larger bronchi.

- Inflammatory Response: The body's immune system mounts an inflammatory response to the invading pathogen or irritant. This leads to the release of inflammatory mediators (e.g., histamine, prostaglandins, bradykinin).

- Mucosal Changes: The inflammation of the bronchial wall results in:

- Mucosal Thickening and Edema: The lining of the airways swells and becomes thicker due to fluid accumulation, narrowing the bronchial lumen.

- Epithelial-Cell Desquamation: The protective epithelial cells that line the airways are damaged and shed.

- Denudation of the Basement Membrane: In some areas, the underlying basement membrane, which supports the epithelial cells, may become exposed, making the airway more vulnerable to further irritation and infection.

- Increased Mucus Production: Goblet cells within the bronchial lining, and submucosal glands, respond to inflammation by overproducing mucus. This mucus often becomes thicker and stickier.

- Airway Obstruction and Symptoms: The combination of mucosal edema, increased and tenacious mucus, and damaged cilia (tiny hair-like structures that help move mucus) leads to partial airway obstruction. This obstruction and irritation trigger the characteristic symptoms of acute bronchitis:

- Cough: The primary symptom, initially non-productive, but often becoming productive as mucus accumulates.

- Wheezing: Due to narrowed airways.

- Shortness of Breath: In more severe cases.

- Resolution: As the immune system clears the infection and the inflammation subsides, the bronchial mucosa heals, and symptoms resolve. The cough may linger due to persistent airway hyperresponsiveness even after the acute inflammation has resolved.

Chronic Bronchitis

Chronic bronchitis is a progressive inflammatory condition primarily characterized by chronic mucus hypersecretion and structural changes in the airways. It is often a key component of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) and is distinct from acute bronchitis in its chronic, often irreversible nature. The pathophysiology involves:

- Chronic Irritant Exposure: The primary trigger is prolonged and repeated exposure to inhaled irritants, with cigarette smoke being the most significant. Other irritants include industrial dusts, air pollution, and occupational chemicals.

- Goblet Cell Hyperplasia and Hypersecretion: In response to chronic irritation, the number and size of mucus-producing goblet cells in the bronchial lining increase (hyperplasia), and they produce excessive amounts of mucus (hypersecretion). Submucosal glands also enlarge and overproduce mucus.

- Impaired Mucociliary Clearance: The cilia, which are responsible for sweeping mucus and trapped particles out of the airways, become damaged, dysfunctional, or are destroyed by the chronic inflammation and irritant exposure. This impairment leads to mucus stasis, further promoting irritation and susceptibility to infection.

- Inflammatory Cell Infiltration and Mediator Release: The chronic irritation triggers a persistent inflammatory response in the bronchial walls. Various inflammatory cells, including macrophages, neutrophils, and lymphocytes, infiltrate the airway. These cells release a range of pro-inflammatory mediators, such as interleukin-8 (IL-8), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), leukotrienes, and proteases (e.g., elastase from neutrophils). These mediators contribute to ongoing inflammation, tissue damage, and mucus production.

- Imbalance of Regulatory Substances: There is often an associated decrease in the release of regulatory substances that normally protect the airway, such as angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) and neutral endopeptidase. This imbalance can exacerbate inflammation and bronchoconstriction.

- Airway Remodeling: Over time, chronic inflammation and irritation lead to structural changes in the airways, known as airway remodeling. This includes:

- Thickening of the bronchial walls due to fibrosis and smooth muscle hypertrophy.

- Narrowing of the small airways, leading to increased airway resistance.

- Loss of elastic recoil in the lungs (if emphysema is also present), further impairing airflow.

- Acute Exacerbations: During an acute exacerbation of chronic bronchitis (AECB), typically triggered by viral or bacterial infections, the bronchial mucous membrane becomes acutely hyperemic (engorged with blood) and edematous. Bronchial mucociliary function is further diminished. This, in turn, leads to a significant increase in airflow impediment because of luminal obstruction to small airways by even more copious and tenacious mucus. The airways become further clogged by cellular debris, inflammatory exudates, and thickened mucus, significantly increasing irritation and worsening symptoms.

- Characteristic Cough: The most characteristic symptom of chronic bronchitis, the persistent productive cough, is directly caused by the copious secretion of mucus that the body attempts to clear from the airways.

Causes of Bronchitis

The causes of bronchitis vary significantly depending on whether it is acute or chronic.

Acute Bronchitis

Acute bronchitis is predominantly caused by infections, usually viral, and is generally self-limiting.

- Approximately 90-95% of acute bronchitis cases in healthy adults are secondary to viral infections. The predominant viruses that are causative include:

- Influenza viruses (Type A and B): Commonly cause seasonal epidemics.

- Parainfluenza viruses: Often cause croup in children but can cause bronchitis in adults.

- Adenoviruses: Can cause a range of respiratory illnesses.

- Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV): A common cause of bronchiolitis in infants but can affect adults.

- Rhinoviruses: The most common cause of the common cold.

- Coronaviruses: Including those that cause the common cold and SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19).

- Bacterial infections are less common primary causes but can occur, often as a secondary infection following a viral illness. Dominant bacterial agents include:

- *Mycoplasma pneumoniae*: Often associated with "walking pneumonia" but can cause bronchitis.

- *Chlamydophila pneumoniae*: Another atypical bacterium causing respiratory infections.

- *Bordetella pertussis* (Whooping Cough): Causes a characteristic paroxysmal cough.

- Less commonly, *Streptococcus pneumoniae* or *Staphylococcus aureus*.

- Smoke Inhalation: From fires, strong chemical fumes, or even very heavy tobacco smoke exposure.

- Polluted Air Inhalation: Exposure to high levels of urban air pollution, smog, or particulate matter.

- Dust: Exposure to occupational dusts (e.g., silica, coal dust) or environmental dust.

- Chemical Fumes: Such as those from cleaning products, industrial chemicals, or solvents.

- Allergens: In individuals with allergic sensitivities, exposure to pollen, pet dander, mold spores, or dust mites can trigger an acute asthmatic bronchitis-like reaction.

Chronic Bronchitis

Chronic bronchitis is primarily caused by long-term exposure to respiratory irritants, leading to persistent inflammation and structural changes in the airways.

- Smog and Air Pollution: Chronic exposure to urban air pollutants, ozone, and particulate matter.

- Industrial Pollutants: Fumes, gases, and dusts encountered in various occupations (e.g., mining, construction, manufacturing). Examples include silica, coal dust, grain dust, cotton dust, and chemical vapors.

- Toxic Chemicals: Repeated exposure to irritant gases such as ammonia, sulfur dioxide, chlorine, or acid fumes.

- Asthma: Chronic inflammation and airway hyperresponsiveness in asthma can contribute to symptoms overlapping with chronic bronchitis.

- Cystic Fibrosis: A genetic disorder leading to thick, sticky mucus production and recurrent infections, causing chronic bronchial inflammation.

- Bronchiectasis: A condition characterized by permanent enlargement of parts of the airways, leading to chronic mucus accumulation and recurrent infections.

- Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency: A genetic condition that predisposes individuals to early-onset emphysema and chronic bronchitis.

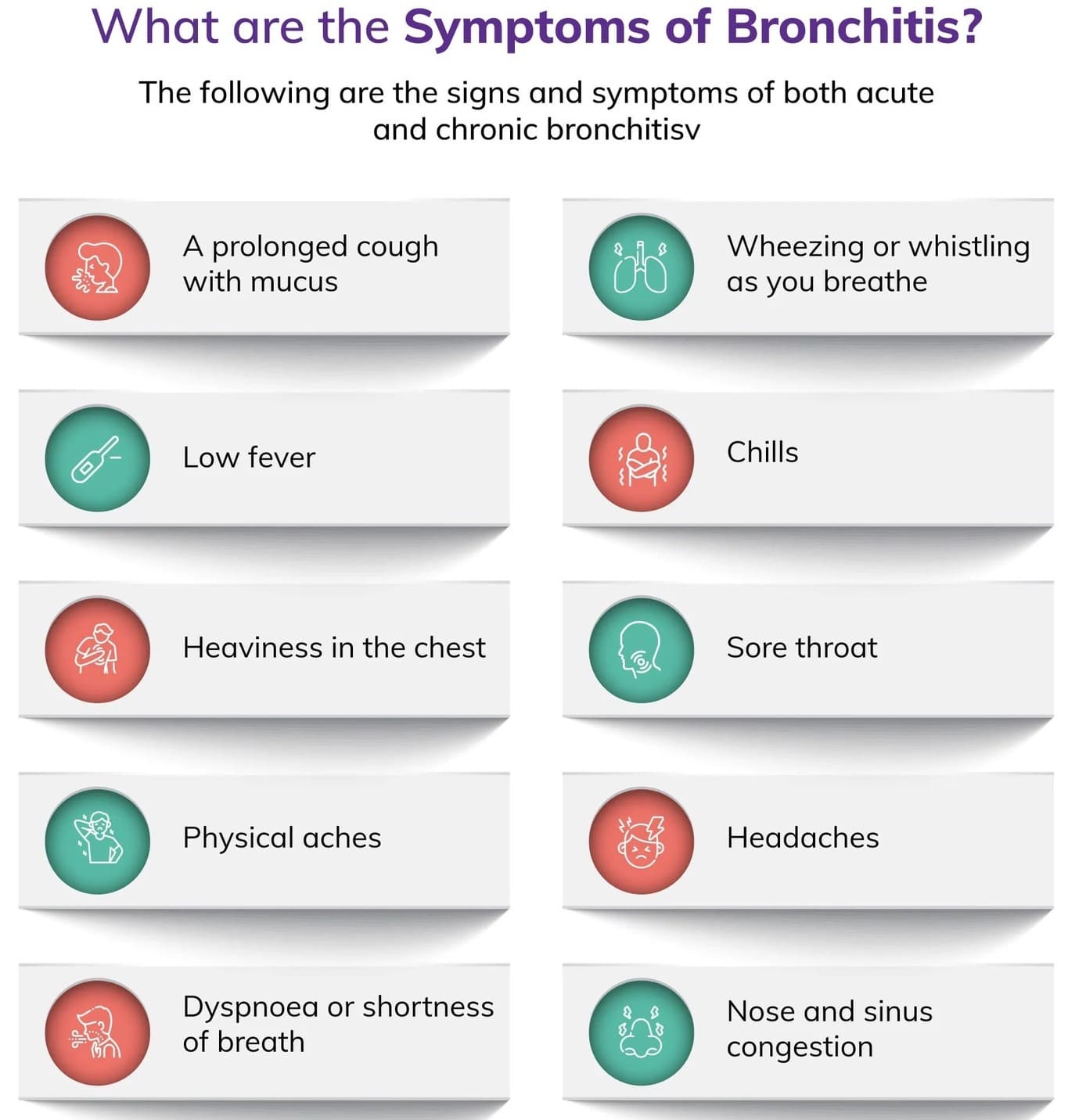

Clinical manifestations of Bronchitis

Acute Bronchitis

Patients with acute bronchitis present with:

- a. Usually, their cough is the predominant complaint and the sputum is clear or yellowish, although sometimes it can be purulent. It's important to note that purulent sputum does not inherently correlate with bacterial infection or necessitate antibiotic use.

- b. The cough after acute bronchitis typically persists for 10 to 20 days but occasionally may last for 4 or more weeks. The median duration of cough after acute bronchitis is 18 days. Paroxysms of cough, especially if accompanied by an inspiratory "whoop" (a high-pitched gasp) or post-tussive emesis (vomiting after coughing), should raise concerns for pertussis (whooping cough).

- c. The cough may be worsened by cold air, smoke, or irritants.

- Runny nose (rhinorrhea)

- Nasal congestion

- Sore throat (pharyngitis)

- Headache

- Muscle aches (myalgia)

Chronic bronchitis

- a. The most common and defining symptom of patients with chronic bronchitis is a persistent cough.

- b. The history of a cough typical of chronic bronchitis is characterized by its presence for most days in a month, lasting for at least 3 months, with at least 2 such consecutive episodes occurring for 2 years in a row.

- c. A productive cough with sputum is present in about 50% of patients. The sputum color may vary from clear, white, yellow, green or at times blood-tinged. The color of sputum may change due to the presence of secondary bacterial infection, but it's important to note that color alone is not a definitive indicator.

- d. Very often, changes in sputum color can be due to peroxidase released by leukocytes in the sputum, giving it a greenish or yellowish hue without a bacterial cause. Therefore, sputum color alone is not a definite indication of bacterial infection and should be interpreted with other clinical signs.

- e. The cough is typically worse in the mornings and in damp or cold weather.

NB: Uncomplicated chronic bronchitis presents primarily with a cough, and there is no evidence of significant airway obstruction physiologically. When airway obstruction is present, it is often indicative of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) with a chronic bronchitis phenotype.

Investigations

- History taking: The diagnosis of bronchitis is primarily made through a detailed history taking, focusing on the onset, duration, and characteristics of symptoms (especially cough), any recent respiratory tract infections, recent or chronic exposure to inhaled irritants (e.g., smoking, occupational hazards, environmental pollutants), and patient's chief complaints.

- Physical examination: This involves a thorough assessment of vital signs, respiratory rate, and oxygen saturation. Key findings during physical examination include:

- Auscultation of lung sounds: May reveal wheezing, rhonchi (coarse rattling sounds), or crackles, indicating inflammation, mucus, or narrowed airways.

- Observation of breathing patterns: Assessment for signs of respiratory distress, such as accessory muscle use, pursed-lip breathing, or tachypnea.

- Palpation of chest: May reveal tenderness due to muscle strain from coughing.

- Inspection: Assessment for cyanosis or clubbing of fingers (in chronic cases).

- Chest X-ray (CXR):

- For acute bronchitis, a chest X-ray is typically normal and is primarily performed to rule out pneumonia or other lung pathologies, especially if symptoms are severe, atypical, or persistent, or if there is a concern for consolidation.

- For chronic bronchitis, a CXR may show increased bronchovascular markings, cardiomegaly (if cor pulmonale is present), or evidence of hyperinflation in advanced cases of COPD. It helps exclude other causes of chronic cough.

- Fiberoptic bronchoscopy: May be both diagnostic (allowing for direct visualization of the airways, collection of qualitative cultures, and biopsy of suspicious lesions) and therapeutic (e.g., for mucus plug removal or re-expansion of lung segments). This is usually reserved for complex or atypical cases, or to rule out other conditions.

- Arterial Blood Gases (ABGs) / Pulse Oximetry:

- Pulse oximetry provides a non-invasive measurement of oxygen saturation (SpO2). Abnormalities may be present, depending on the extent of lung involvement and underlying lung disease.

- ABGs provide a more detailed assessment of oxygenation (PaO2), ventilation (PaCO2), and acid-base balance. In chronic bronchitis, chronic hypoxemia and hypercapnia may be present, especially during exacerbations.

- Gram stain/cultures:

- Sputum collection: Can be done for Gram stain and culture to identify bacterial pathogens and determine antibiotic sensitivity, especially if bacterial infection is suspected (e.g., purulent sputum with fever and worsening symptoms).

- Other samples: Needle aspiration of empyema, pleural fluid, transtracheal or transthoracic fluids, lung biopsies, and blood cultures may be done to recover causative organisms in severe cases or when pneumonia is suspected. More than one type of organism may be present; common bacteria include *Streptococcus pneumoniae*, *Staphylococcus aureus*, alpha-hemolytic streptococcus, *Haemophilus influenzae*; also viral pathogens like Cytomegalovirus (CMV). Note: Sputum cultures may not identify all offending organisms, and blood cultures may show transient bacteremia.

- Complete Blood Count (CBC):

- Leukocytosis (elevated white blood cell count) is usually present in bacterial infections, although a low white blood cell (WBC) count may be present in viral infection, immunosuppressed conditions such as AIDS, and overwhelming bacterial pneumonia.

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) are non-specific inflammatory markers that may be elevated.

- Serologic studies: E.g., viral titers (for influenza, adenovirus, RSV), *Legionella* titers, or cold agglutinins (for *Mycoplasma pneumoniae*). These assist in the differential diagnosis of specific organisms, especially in atypical presentations or outbreaks.

- Pulmonary Function Studies (PFTs):

- These tests measure lung volumes, capacities, and airflow. In acute bronchitis, PFTs are typically normal or show mild, transient obstruction.

- In chronic bronchitis, especially when progressing to COPD, volumes may be decreased (due to congestion and alveolar collapse), airway pressure may be increased, and compliance decreased. Obstructive patterns with reduced FEV1/FVC ratio are characteristic. Shunting may be present, leading to hypoxemia.

- Electrolytes: Sodium and chloride levels may be low, particularly in cases of severe illness or syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH) which can sometimes complicate severe respiratory infections.

- Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency Screening: Recommended in patients with early-onset emphysema or a family history of lung disease, as it is an inherited risk factor for COPD.

Management

Medical Management

Acute Bronchitis

Acute bronchitis is predominantly self-limiting, and treatment is typically symptomatic and supportive, focusing on relieving discomfort and promoting recovery.

- For cough relief, both non-pharmacological and pharmacological therapy should be offered:

- a. Non-pharmacological therapy includes:

- Drinking plenty of fluids (warm water, herbal tea, clear broths) to thin secretions and keep the throat moist.

- Consuming soothing agents like honey (not for infants under 1 year due to botulism risk), ginger, or using throat lozenges or hard candies to relieve throat irritation.

- Using a cool-mist humidifier in the bedroom to moisten the air and help loosen mucus.

- Avoiding irritants such as cigarette smoke (including secondhand smoke), air pollution, and chemical fumes.

- b. Pharmacological antitussive agents:

- Dextromethorphan: An over-the-counter cough suppressant.

- Codeine: A narcotic cough suppressant, sometimes prescribed for severe cough, but its use is generally discouraged due to its addictive potential and side effects.

- Guaifenesin: An expectorant that helps to thin mucus, making it easier to cough up. Often found in combination with antitussives.

- It's important to use these agents judiciously as suppressing a productive cough excessively can hinder clearance of secretions.

- a. Non-pharmacological therapy includes:

- For treatment of wheezing or bronchospasm: Inhaled bronchodilators (e.g., short-acting beta-agonists like albuterol) may be prescribed to reduce bronchospasm, open airways, and promote sputum expectoration, especially if the patient has underlying reactive airway disease or significant wheezing.

- Analgesic and antipyretic agents: Over-the-counter medications like acetaminophen (paracetamol) or ibuprofen can be used to treat associated malaise, myalgia (muscle aches), headache, and fever.

- Corticosteroids: Oral corticosteroids (e.g., prednisone) or inhaled corticosteroids may be considered in cases with significant inflammation or bronchospasm that is unresponsive to bronchodilators, to help with the inflammation. However, their routine use in acute bronchitis is not recommended.

- Lifestyle modification: Smoking cessation is paramount for preventing chronic bronchitis and recurrent acute episodes. The avoidance of allergens and environmental pollutants (e.g., industrial dust, chemicals) also plays an important role in the avoidance of recurrence and complications.

- Vaccinations:

- Influenza vaccine: Especially recommended annually for special groups including adults older than 65, children younger than two years (older than six months), pregnant women, and residents of nursing homes and long-term care facilities.

- Pneumococcal vaccine: Recommended for individuals at higher risk of developing complications (e.g., pneumonia), including people with chronic lung diseases (asthma, COPD), immunocompromised adults, and adults older than 65.

- Antibiotics: A course of oral antibiotics (e.g., a macrolide, doxycycline, or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole) may be instituted in specific situations, but their routine use for acute bronchitis is highly controversial and generally not recommended because most cases are viral. Antibiotics are considered only if:

- Bacterial infection is strongly suspected (e.g., high fever, severe purulent sputum, signs of pneumonia on X-ray, or prolonged symptoms).

- The patient is immunocompromised.

- There's a concern for pertussis (treated with macrolides).

Chronic bronchitis

The primary aim of treatment for chronic bronchitis is to relieve symptoms, prevent complications (such as exacerbations and progression to COPD), and slow the progression of the disease. The primary goals of therapy are aimed at reducing the overproduction of mucus, controlling inflammation, managing cough, and improving airflow.

Pharmacological interventions are the following:

- Bronchodilators: These are cornerstone medications for symptomatic relief by opening the airways.

- Short-acting β-Adrenergic receptor Agonists (SABAs) like albuterol (salbutamol): Used as rescue inhalers for quick relief of acute shortness of breath or wheezing.

- Long-acting β-Adrenergic receptor Agonists (LABAs) like salmeterol, formoterol: Used for maintenance therapy to provide sustained bronchodilation.

- Anticholinergic agents (Short-acting: ipratropium; Long-acting: tiotropium, aclidinium): Help by blocking acetylcholine, which leads to bronchodilation, increasing the airway lumen, and reducing mucus production. They also aid in increasing ciliary function and by increasing mucous hydration. Often used in combination with beta-agonists.

- Glucocorticoids: These powerful anti-inflammatory medications reduce inflammation and mucus production.

- Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) like fluticasone, budesonide: Often used in combination with LABAs (e.g., in COPD exacerbations) to reduce exacerbations and improve quality of life. However, their long-term use can induce systemic side effects (e.g., osteoporosis, diabetes, hypertension, increased risk of pneumonia) and should be administered under medical supervision and for the shortest effective periods.

- Oral corticosteroids: Used for acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis to reduce severe inflammation, but not for long-term daily use due to significant side effects.

- Antibiotic therapy: Generally not indicated in the stable treatment of chronic bronchitis, as it is a chronic inflammatory condition, not an infection. However:

- Acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis (AECB) with signs of bacterial infection (e.g., increased sputum purulence, volume, or dyspnea) often warrant antibiotic treatment.

- Long-term macrolide therapy (e.g., azithromycin) has been shown to have anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory properties and can reduce the frequency of exacerbations in some patients with severe COPD and chronic bronchitis, hence it may have a role in the treatment of chronic bronchitis, but this is typically reserved for severe cases and involves careful risk-benefit assessment.

- Phosphodiesterase-4 (PDE4) inhibitors: Roflumilast is an example of this class. These oral medications decrease inflammation and promote airway smooth muscle relaxation by preventing the hydrolysis of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), a substance whose degradation leads to the release of inflammatory mediators. They are used in severe COPD associated with chronic bronchitis and a history of exacerbations.

- Mucolytics: Medications like N-acetylcysteine or carbocysteine may be used to thin mucus, making it easier to clear, though their benefit is often modest.

- Oxygen therapy: For patients with chronic hypoxemia, supplemental oxygen therapy can improve survival and quality of life.

Non Pharmacological Measures

- The most critical non-pharmacological intervention is smoking cessation. Smoking cessation significantly improves mucociliary function, decreases goblet cell hyperplasia (which contributes to mucus overproduction), and has been shown to reduce airway injury resulting in lower levels of exfoliated mucus in tracheobronchial cells. It is the single most effective intervention to slow disease progression.

- Pulmonary rehabilitation: An important and comprehensive part of treatment for chronic bronchitis and COPD, which consists of:

- Education: On disease management, medications, self-care, and warning signs of exacerbations.

- Lifestyle modification: Including nutrition, stress management, and avoidance of triggers.

- Regular physical activity: Tailored exercise programs to improve exercise tolerance, muscle strength, and reduce dyspnea.

- Breathing techniques: Such as pursed-lip breathing and diaphragmatic breathing to optimize lung function.

- Avoidance of exposure to known pollutants: Either at work or in the living environment (e.g., air pollution, secondhand smoke, occupational dusts).

- Nutritional support: Patients with chronic bronchitis/COPD may experience weight loss or malnutrition due to increased energy expenditure for breathing or difficulty eating, so nutritional counseling is important.

- Psychological support: Addressing anxiety and depression, which are common in chronic respiratory conditions.

Nursing management

Nursing management for bronchitis involves a holistic approach, focusing on assessment, symptom management, patient education, and prevention of complications. While some interventions refer to general principles, specific applications for bronchitis are highlighted below.

- a. Refer to the notes of general assessment nursing interventions, but specifically for bronchitis:

- Respiratory Assessment: Auscultate lung fields for adventitious sounds (wheezing, rhonchi, crackles), assess respiratory rate, depth, and effort. Note presence of dyspnea, use of accessory muscles, pursed-lip breathing. Monitor oxygen saturation via pulse oximetry.

- Cough Assessment: Characterize the cough (productive/non-productive, frequency, severity, timing). Assess sputum characteristics (color, consistency, amount, odor). Inquire about any triggers for the cough.

- Vital Signs: Monitor temperature for fever, pulse for tachycardia, and blood pressure.

- Pain Assessment: Evaluate for chest pain or abdominal muscle pain related to coughing, using a pain scale.

- Hydration Status: Assess skin turgor, mucous membranes, and urine output to determine hydration levels.

- Activity Tolerance: Assess the patient's ability to perform activities of daily living (ADLs) and any limitations due to dyspnea or fatigue.

- History: Detailed history of smoking, exposure to irritants, vaccination status, and any underlying lung conditions (e.g., asthma, COPD).

- a. Refer to the notes of general fever nursing interventions, but specifically for bronchitis:

- Administer antipyretics (e.g., acetaminophen, ibuprofen) as prescribed.

- Provide comfort measures: cool compresses, light clothing, and ensuring a comfortable room temperature.

- Encourage increased oral fluid intake to prevent dehydration associated with fever.

- Monitor temperature regularly and assess for signs of worsening infection.

- a. Refer to the nursing interventions of influenza under infection prevention, but specifically for bronchitis:

- Educate on good hand hygiene practices for both the patient and caregivers.

- Advise avoiding close contact with individuals who are sick.

- Encourage annual influenza vaccination and pneumococcal vaccination as recommended, especially for at-risk groups.

- Instruct on proper disposal of tissues and respiratory etiquette (coughing/sneezing into elbow).

- For chronic bronchitis, reinforce adherence to prescribed medications to prevent exacerbations, which can be triggered by infections.

- a. Position head midline with flexion appropriate for age/condition to gain or maintain an open airway. For adults, semi-Fowler's or high-Fowler's position is generally preferred to maximize lung expansion.

- b. Elevate the head of the bed (HOB) to decrease pressure on the diaphragm, promote lung expansion, and facilitate drainage of secretions.

- c. Observe signs of worsening infection or increased secretions to identify an infectious process or exacerbation.

- d. Auscultate breath sounds and assess air movement frequently to ascertain status and note progress or deterioration. Document changes.

- e. Instruct the patient to increase fluid intake (2-3 liters/day unless contraindicated by co-morbidities like heart failure or renal disease) to help liquefy secretions, making them easier to expectorate.

- f. Demonstrate and encourage effective coughing and deep-breathing techniques (e.g., huff cough, diaphragmatic breathing) to maximize effort and facilitate clearance of secretions. Assist with chest physiotherapy (postural drainage, percussion, vibration) if indicated and prescribed.

- g. Keep the patient's back dry and linen clean to prevent skin breakdown and further complications, especially if there is excessive sweating or sputum production.

- h. Turn the patient every 2 hours (for bedridden patients) to prevent pooling of secretions, promote lung expansion, and prevent possible aspirations.

- i. Administer bronchodilators (e.g., nebulizers, metered-dose inhalers) as prescribed, monitoring for effectiveness and side effects (e.g., tachycardia, tremors).

- j. Encourage ambulation and mobilization as tolerated to promote lung expansion and secretion clearance.

- a. Place patient in semi-Fowler's or high-Fowler's position to allow for maximum lung expansion and ease of breathing.

- b. Increase fluid intake as applicable and tolerated to liquefy secretions and improve mucociliary clearance.

- c. Keep patient's back dry and provide frequent linen changes to maintain comfort and prevent skin issues.

- d. Place a pillow when the client is sleeping to provide adequate lung expansion while sleeping, possibly by elevating the head slightly.

- e. Instruct how to splint the chest wall with a pillow or hands for comfort during coughing and to reduce pain. Elevate the head over the body as appropriate to promote physiological ease of maximal inspiration.

- f. Maintain a patent airway; suctioning of secretions may be done as ordered to remove secretions that obstruct the airway, especially in patients with impaired cough reflex or thick secretions.

- g. Provide respiratory support: Oxygen inhalation is provided per doctor’s order to aid in relieving patient from dyspnea and to maintain adequate oxygen saturation levels (e.g., SpO2 >90%). Monitor oxygen flow rate and effectiveness.

- h. Administer prescribed cough suppressants and analgesics. Be cautious, however, because opioids may depress respirations more than desired. Use judiciously to promote patient comfort without compromising respiratory drive.

- i. Educate on pursed-lip breathing and diaphragmatic breathing techniques to improve ventilation and reduce air trapping.

- j. Provide periods of rest between activities to conserve energy and reduce dyspnea.

- k. Monitor for signs of respiratory distress and immediately report any worsening symptoms to the physician.

- Educate patients about their condition, medication regimen (purpose, dose, side effects, proper inhaler technique), and when to seek medical attention (e.g., worsening cough, increased sputum, fever, increased dyspnea).

- Counsel on smoking cessation strategies and provide resources.

- Discuss avoidance of environmental triggers and irritants.

- Teach energy conservation techniques for chronic bronchitis patients.

- Encourage regular exercise within tolerance limits.

Nursing Diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses provide a clinical judgment about individual, family, or community responses to actual or potential health problems/life processes. For bronchitis, common nursing diagnoses, based on NANDA International (NANDA-I) classifications, might include:

- Ineffective Airway Clearance related to increased mucus production, thick tenacious secretions, impaired ciliary function, and/or bronchospasm, as evidenced by abnormal breath sounds (e.g., rhonchi, wheezes), ineffective cough, dyspnea, and/or changes in respiratory rate/rhythm.

- Impaired Gas Exchange related to altered oxygen supply (e.g., narrowed airways, mucus plugging) and/or ventilation-perfusion imbalance, as evidenced by dyspnea, abnormal arterial blood gases (e.g., decreased PaO2, increased PaCO2), cyanosis, and/or abnormal breath sounds. (More prevalent in chronic bronchitis/COPD exacerbations).

- Ineffective Breathing Pattern related to inflammatory process, mucus obstruction, anxiety, and/or pain (e.g., from coughing), as evidenced by dyspnea, tachypnea, use of accessory muscles, pursed-lip breathing, and/or altered chest excursion.

- Acute Pain related to persistent coughing, muscle strain (e.g., intercostal, abdominal), and/or chest discomfort secondary to inflammation, as evidenced by patient reports of pain, grimacing, guarding behavior, and/or restlessness.

- Fatigue related to increased work of breathing, persistent coughing, sleep disturbance, and/or systemic infection, as evidenced by patient reports of overwhelming lack of energy, lethargy, decreased activity level, and/or difficulty performing ADLs.

- Activity Intolerance related to imbalance between oxygen supply and demand, dyspnea, and/or fatigue, as evidenced by verbal reports of fatigue/weakness, exertional dyspnea, abnormal heart rate or blood pressure response to activity, and/or decreased ability to perform ADLs. (More common in chronic bronchitis).

- Deficient Knowledge regarding disease process, treatment regimen, symptom management, and/or prevention of recurrence/exacerbations, as evidenced by patient questions, inaccurate follow-through of instructions, and/or development of preventable complications.

- Risk for Infection related to stasis of secretions, impaired ciliary action, and/or compromised immune response. (Applies to both acute bronchitis progressing to pneumonia or chronic bronchitis with increased susceptibility to exacerbations).

- Excessive Anxiety related to dyspnea, fear of suffocation, change in health status, and/or uncertainty about the future, as evidenced by patient reports of nervousness, restlessness, increased respiratory rate, and/or apprehension.

Complications of Bronchitis

While acute bronchitis is usually self-limiting and resolves without complications, chronic bronchitis can lead to significant and often debilitating complications. Complications can also arise from acute bronchitis, especially in vulnerable populations (e.g., very young, elderly, immunocompromised).

Complications of Acute Bronchitis

- Pneumonia: The most common and serious complication. The inflammation and impaired mucociliary clearance can allow bacterial or viral infections to spread from the bronchi to the lung parenchyma, leading to pneumonia. This risk is higher in individuals with weakened immune systems, underlying lung disease, or the very young/elderly.

- Acute Exacerbation of Underlying Chronic Lung Disease: In individuals with pre-existing conditions like asthma or COPD, acute bronchitis can trigger a severe exacerbation of their underlying disease, leading to worsening symptoms, increased airway obstruction, and potentially respiratory failure.

- Persistent Cough: While most coughs resolve within 2-3 weeks, post-infectious cough can linger for several weeks (e.g., 4-8 weeks) due to airway hypersensitivity, even after the infection has cleared. This is often bothersome but not usually serious.

- Bronchiolitis: More common in infants and young children, severe inflammation can extend to the smaller airways (bronchioles), causing significant respiratory distress.

- Dehydration: Especially in infants and elderly, fever and increased respiratory rate can lead to fluid loss if fluid intake is not maintained.

- Ear Infections (Otitis Media) and Sinusitis: Upper respiratory tract infections that lead to bronchitis can also predispose to complications in adjacent structures.

Complications of Chronic Bronchitis

Chronic bronchitis, particularly as part of COPD, can lead to a range of severe and progressive complications affecting various body systems.

- Recurrent Acute Exacerbations of Chronic Bronchitis (AECB): These are acute events characterized by a worsening of respiratory symptoms (increased dyspnea, cough, sputum volume, and/or purulence) beyond day-to-day variations. AECBs are often triggered by bacterial or viral infections, air pollution, or other irritants and can lead to significant morbidity, hospitalizations, and accelerate lung function decline.

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD): Chronic bronchitis is a major component and a clinical diagnosis of COPD. Over time, the persistent inflammation and airway remodeling lead to irreversible airflow limitation, reduced lung function, and progressive dyspnea.

- Emphysema: Often coexists with chronic bronchitis in COPD. Emphysema involves the destruction of the alveolar walls, leading to enlarged air spaces and loss of elastic recoil, further contributing to airflow obstruction and impaired gas exchange.

- Respiratory Failure: As the disease progresses, the lungs become unable to adequately oxygenate the blood and/or remove carbon dioxide, leading to chronic hypoxemia (low oxygen) and hypercapnia (high CO2). This can necessitate supplemental oxygen therapy and, in severe exacerbations, mechanical ventilation.

- Cor Pulmonale (Right-Sided Heart Failure): Chronic hypoxemia leads to pulmonary vasoconstriction, increasing pulmonary artery pressure (pulmonary hypertension). This increased workload on the right ventricle of the heart can eventually lead to its enlargement and failure, resulting in peripheral edema (swelling in the ankles, legs), jugular venous distension, and hepatomegaly.

- Pulmonary Hypertension: Persistently elevated blood pressure in the arteries of the lungs, often a precursor to cor pulmonale.

- Pneumothorax: In severe cases of COPD with emphysema, ruptured bullae (enlarged air sacs) can lead to a collapsed lung.

- Polycythemia: Chronic hypoxemia can stimulate the kidneys to produce erythropoietin, leading to an increase in red blood cell production. This thickens the blood, increasing the risk of blood clots.

- Weight Loss and Malnutrition: Increased energy expenditure for breathing, reduced appetite (due to dyspnea, fatigue, or depression), and systemic inflammation can lead to unintended weight loss and malnutrition.

- Osteoporosis: Chronic inflammation, corticosteroid use, and reduced physical activity in COPD/chronic bronchitis patients contribute to bone density loss and increased fracture risk.

- Muscle Wasting and Dysfunction: Systemic inflammation, hypoxemia, and reduced activity can lead to skeletal muscle weakness and atrophy, further impacting exercise tolerance and quality of life.

- Depression and Anxiety: The chronic nature of the disease, debilitating symptoms, and impact on quality of life often lead to significant psychological distress.

- Increased Susceptibility to Infections: Impaired mucociliary clearance and chronic inflammation make individuals with chronic bronchitis more vulnerable to recurrent respiratory infections.

- Respiratory Acidosis: In advanced stages or during exacerbations, the body's inability to effectively clear CO2 can lead to a build-up of acid in the blood.