Lymphedema (pronounced lim-fa-DEE-ma) is a chronic, progressive, and often debilitating condition characterized by localized tissue swelling and fluid retention, which occurs when the lymphatic system is impaired or damaged.

- Chronic and Progressive:

- Chronic: It is a long-term condition that typically does not resolve on its own.

- Progressive: If left untreated, the swelling tends to worsen over time, leading to more significant tissue changes.

- Localized Tissue Swelling and Fluid Retention:

- The most visible and primary symptom is swelling, usually in one or more limbs (arms or legs), but it can also affect other body parts such as the trunk, head and neck, or genitalia.

- The fluid that accumulates is rich in protein, which is a distinguishing feature from other types of edema.

- Impaired or Damaged Lymphatic System:

- This is the defining characteristic. Lymphedema specifically results from a failure of the lymphatic system to adequately drain lymph fluid from a particular area of the body.

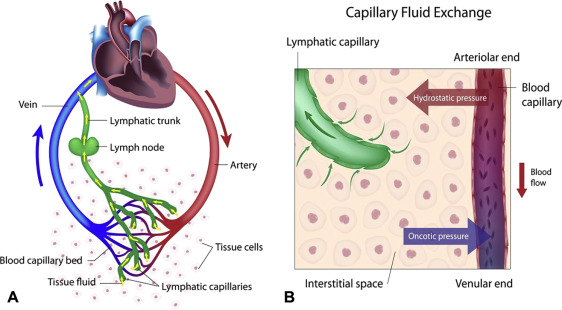

- The lymphatic system is a network of vessels, nodes, and organs responsible for collecting excess interstitial fluid (lymph) from tissues, filtering it, and returning it to the bloodstream.

- When this system is compromised, lymph fluid accumulates in the interstitial spaces, leading to swelling.

- Distinguishing from General Edema:

- Edema is a general term for swelling caused by fluid accumulation. Many conditions can cause edema (e.g., heart failure, kidney disease, venous insufficiency).

- Lymphedema is a specific type of edema characterized by:

- High Protein Content: Unlike many other forms of edema where the fluid is mainly water and electrolytes, lymphedema fluid is rich in protein. This high protein content is crucial because it draws more water into the interstitial space, stimulates fibroblast activity, and contributes to tissue fibrosis (hardening/thickening of the skin and subcutaneous tissue).

- Non-pitting (in later stages): While early lymphedema may be pitting (an indentation remains after pressure is applied), as the condition progresses and fibrosis occurs, the tissue becomes harder and the swelling becomes non-pitting.

- Asymmetrical (often): Lymphedema often affects one limb or one side of the body, though it can be bilateral if the underlying cause affects both sides. Other systemic edemas are typically symmetrical.

In essence, lymphedema is the specific and chronic swelling that occurs when the body's natural drainage system for protein-rich fluid (the lymphatic system) is not working correctly.

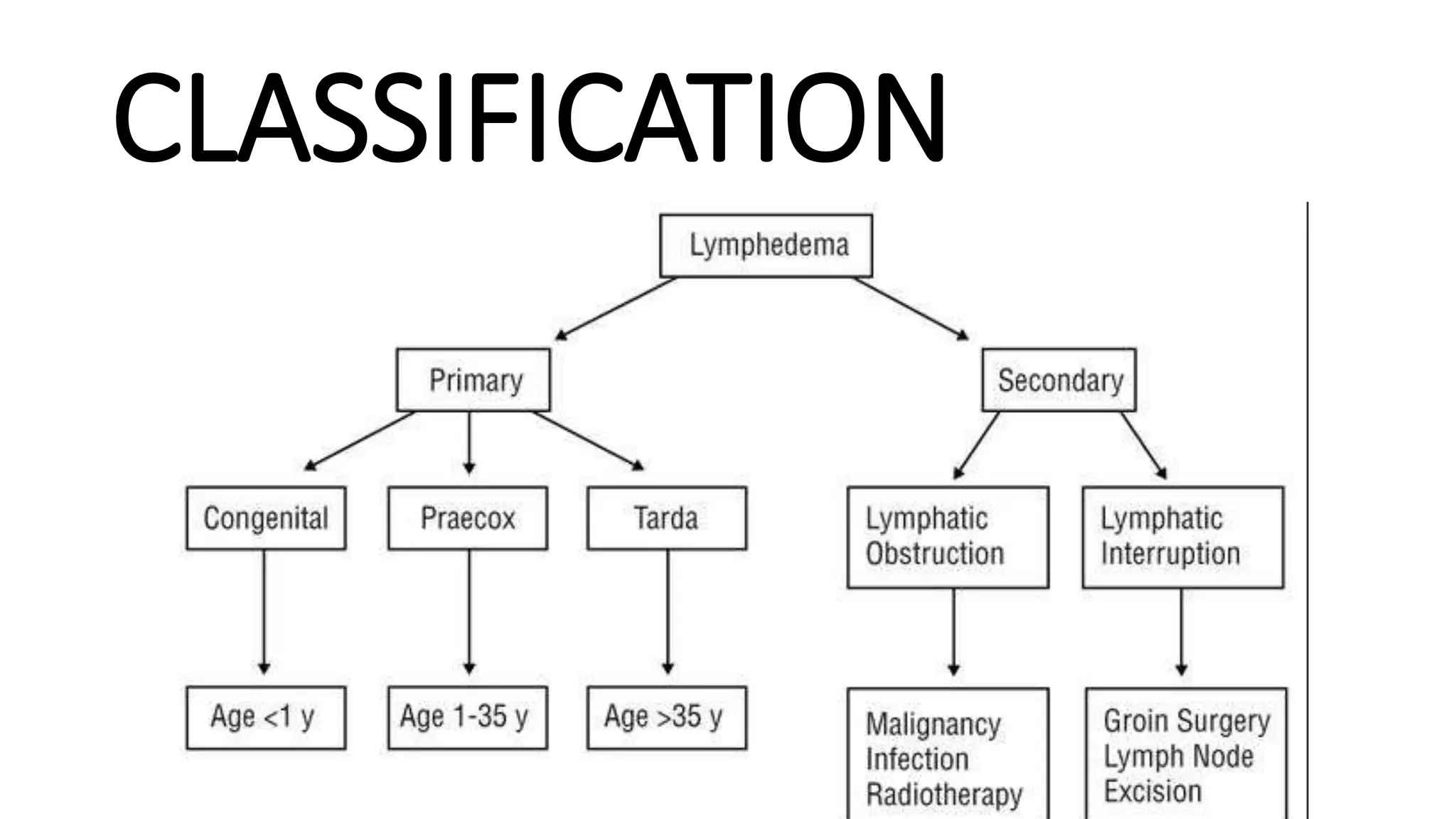

Lymphedema is broadly classified into two main types: primary lymphedema and secondary lymphedema. The distinction lies in whether the impairment of the lymphatic system is due to a congenital abnormality or an acquired damage/disruption.

- Definition: Primary lymphedema results from an inherited or congenital abnormality or malformation of the lymphatic system itself. This means the lymphatic vessels or nodes are underdeveloped, malformed, or absent from birth, or develop abnormally later in life without an identifiable external cause.

- Onset: Can be present at birth, develop during puberty, or even manifest in adulthood.

- Causes (Congenital Malformations): These are structural abnormalities of the lymphatic system, often genetic in origin, leading to insufficient lymphatic transport capacity.

- Aplasia: Complete absence of lymphatic vessels in a given area.

- Hypoplasia: Underdevelopment or reduced number of lymphatic vessels, or vessels that are too small. This is the most common cause of primary lymphedema.

- Hyperplasia (or Megalymphatics): Abnormally dilated and tortuous lymphatic vessels, often with incompetent valves, leading to reflux and inefficient drainage.

- Lymphatic Dysfunction: Impaired function of otherwise normally structured vessels, e.g., due to impaired contractility.

- Clinical Syndromes Associated with Primary Lymphedema:

- Congenital Lymphedema (Milroy's Disease): Present at birth or develops within the first 2 years of life. Often affects one or both lower limbs. It is caused by mutations in the FLT4 gene (VEGFR3), leading to lymphatic hypoplasia.

- Lymphedema Praecox (Meige's Disease): The most common form of primary lymphedema, usually developing around puberty or before age 35. Affects primarily females and typically the lower limbs. May be associated with mutations in the FOXC2 gene.

- Lymphedema Tarda: Develops after age 35.

- Other Genetic Syndromes: Primary lymphedema can also be a feature of certain genetic syndromes, such as Turner syndrome, Noonan syndrome, and yellow nail syndrome.

- Definition: Secondary lymphedema is much more common than primary lymphedema. It results from damage to or obstruction of a previously normal lymphatic system. The lymphatic system is acquiredly injured, leading to its inability to adequately drain lymph fluid.

- Onset: Typically develops after an event that damages the lymphatic system, such as surgery, radiation, infection, or trauma.

- Causes (Acquired Damage/Disruption):

- Cancer Treatment (Most Common Cause in Developed Countries):

- Lymph Node Dissection/Removal: Surgical removal of lymph nodes (e.g., sentinel lymph node biopsy, axillary dissection for breast cancer, groin dissection for melanoma, pelvic dissection for gynecological cancers) is a major risk factor. This physically removes critical drainage pathways.

- Radiation Therapy: Radiation used to treat cancer can damage lymphatic vessels and nodes, causing fibrosis and scarring that impede lymph flow.

- Infection (Most Common Cause Worldwide):

- Filariasis (Elephantiasis): A parasitic infection (caused by filarial worms) transmitted by mosquitoes. The adult worms live in and block lymphatic vessels, causing severe damage and leading to massive lymphedema, particularly in the lower limbs and genitalia. This is a major cause of lymphedema in tropical and subtropical regions.

- Cellulitis/Erysipelas: Recurrent severe bacterial infections of the skin and subcutaneous tissue can cause inflammation and scarring of lymphatic vessels, leading to damage.

- Trauma/Injury: Severe burns, crush injuries, or extensive wounds can directly damage or disrupt lymphatic vessels.

- Surgery (Non-Cancer Related): Any extensive surgery that involves large incisions or removal of tissue can inadvertently damage lymphatic pathways.

- Venous Insufficiency: Severe, chronic venous insufficiency can lead to an overload of the lymphatic system. While primarily venous edema, it can eventually lead to lymphatic damage and secondary lymphedema (phlebolymphedema).

- Obesity: Severe obesity can place mechanical stress on lymphatic vessels, impair lymphatic flow, and is increasingly recognized as a significant risk factor and contributor to lymphedema development and progression.

- Immobility/Lack of Muscle Pump: Prolonged immobility can reduce the effectiveness of the muscle pump, which aids lymphatic flow, exacerbating existing lymphatic issues or contributing to edema.

- Tumor Obstruction: Tumors themselves can grow and directly compress or invade lymphatic vessels and nodes, blocking lymph drainage.

- Cancer Treatment (Most Common Cause in Developed Countries):

The development of lymphedema is a multifactorial process, influenced by a primary insult to the lymphatic system coupled with various risk factors that can exacerbate or trigger the condition.

These factors don't necessarily cause lymphatic damage themselves but increase the likelihood or severity of lymphedema when lymphatic damage is present or imminent.

- Genetics/Family History: A family history of primary lymphedema increases risk.

- Obesity: As mentioned, it's a significant risk factor for both onset and progression.

- Increased Age: The lymphatic system may become less efficient with age.

- Presence of Scar Tissue: Extensive scarring can obstruct lymphatic pathways.

- Impaired Wound Healing: Can lead to chronic inflammation and further lymphatic damage.

- Chronic Inflammation: Any condition causing persistent inflammation can contribute.

- Female Sex: Women are more susceptible to certain cancers that involve lymph node dissection (e.g., breast cancer), increasing their risk of secondary lymphedema.

- Severity of Initial Lymphatic Insult: More extensive surgery, higher doses of radiation, or severe infections increase the risk.

Lymphedema originates from a fundamental imbalance between the production of interstitial fluid and its drainage by the lymphatic system. This leads to a vicious cycle of fluid accumulation, inflammation, and progressive tissue changes.

- Reduced Lymphatic Transport Capacity:

- Primary Lymphedema: The lymphatic system is intrinsically deficient from birth. Its maximal transport capacity (MTC) is inherently lower than normal.

- Secondary Lymphedema: A previously normal lymphatic system is damaged. This damage reduces the number and function of lymphatic vessels and nodes, thereby lowering the MTC.

- The "Safety Factor": A healthy lymphatic system has a significant "safety factor," meaning it can handle a much higher volume of fluid (up to 10-20 times normal) than it typically drains without swelling. When the MTC drops below the actual lymphatic load, lymphedema begins.

- Accumulation of Protein-Rich Interstitial Fluid:

- When the lymphatic system's capacity is overwhelmed or reduced, the interstitial fluid cannot be adequately drained.

- Crucially, the lymphatic system is the only pathway for large proteins, cellular debris, and large molecules to be removed from the interstitial space.

- Therefore, in lymphedema, there is a characteristic accumulation of protein-rich fluid in the affected tissues.

The accumulation of protein-rich fluid is not benign. The high protein concentration in the interstitial space acts as an osmotic force, drawing even more water from the capillaries into the tissue, thereby exacerbating the swelling. Furthermore, this protein-rich environment initiates a cascade of inflammatory and fibrotic changes:

- Inflammation and Immune Response:

- Macrophage Activation: The stagnant, protein-rich lymph is an ideal medium for chronic low-grade inflammation. Macrophages are attracted to the area and activated.

- Cytokine Release: Activated macrophages and other immune cells release pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-1, IL-6) and growth factors (e.g., TGF-β, VEGF-C).

- Impaired Local Immunity: The impaired lymphatic drainage also means that immune cells cannot effectively patrol and respond to local infections, making the lymphedematous limb more prone to recurrent infections (e.g., cellulitis), which in turn further damages the lymphatic system.

- Stimulation of Fibrosis (Connective Tissue Proliferation):

- Fibroblast Activation: The high protein concentration and the persistent inflammatory mediators (especially TGF-β) stimulate fibroblasts in the subcutaneous tissue to produce and deposit excess collagen and other extracellular matrix components.

- Adipose Tissue Accumulation: There is also a significant proliferation of adipocytes (fat cells) in the affected area. This is a characteristic feature of chronic lymphedema, contributing significantly to the increased limb volume and hardening.

- Increased Tissue Viscosity: The deposition of collagen and fat leads to hardening and thickening of the subcutaneous tissue, making the limb feel firm and eventually non-pitting. This is known as fibrosis or sclerosis.

- Further Compromise of Lymphatic Function:

- The chronic inflammation and fibrosis within the tissues can further compress and destroy remaining functional lymphatic vessels, leading to a further reduction in MTC. This creates a self-perpetuating cycle where lymphatic insufficiency leads to fluid accumulation, which leads to inflammation and fibrosis, which then worsens lymphatic insufficiency.

This pathological process leads to the characteristic signs and symptoms of lymphedema, progressing through stages:

- Initial Stages (Stage 0, Stage 1):

- Pitting Edema: Early lymphedema is often characterized by pitting edema (an indentation remains after pressure is applied), as the tissue is still relatively soft.

- Reversible Swelling: The swelling may partially or fully resolve with elevation or overnight rest.

- Later Stages (Stage 2, Stage 3):

- Non-pitting Edema: As fibrosis and fat deposition increase, the tissue becomes firmer, and the swelling becomes non-pitting.

- Skin Changes: The skin becomes thickened, hardened, and takes on an "orange peel" appearance (peau d'orange). There may be hyperkeratosis (thickening of the outer layer of the skin), papillomatosis (wart-like growths), and skin folds deepen.

- Loss of Function: The increased limb volume and tissue changes can lead to pain, discomfort, reduced range of motion, and impaired mobility.

- Increased Susceptibility to Infection: Due to impaired local immunity and stagnant fluid, recurrent episodes of cellulitis are common, further damaging the lymphatic system.

- Lymphangiectasia/Dermal Backflow: In severe cases, lymphatic vessels in the skin may dilate, sometimes leaking lymph (lymphorrhea).

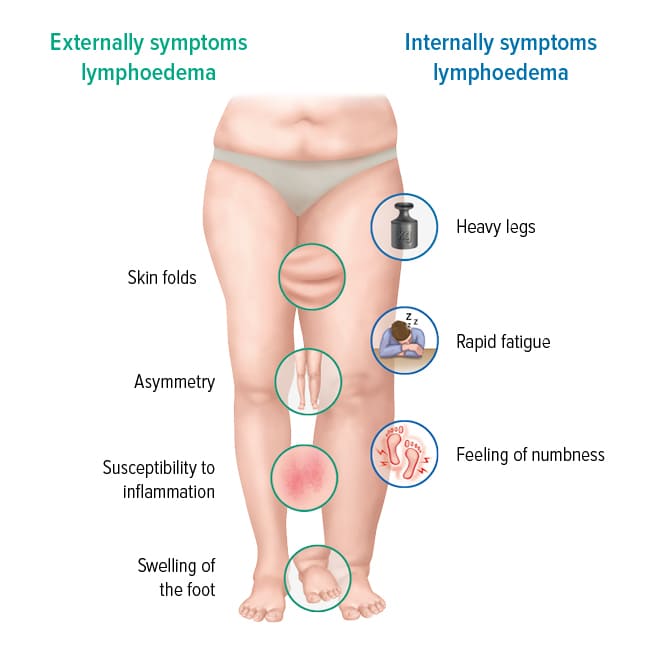

The clinical presentation of lymphedema can vary based on its cause, location, and severity, but there are characteristic signs and symptoms that guide diagnosis.

- Swelling (Edema):

- Primary Symptom: The most obvious sign. Can affect arms, legs, trunk, head/neck, or genitalia.

- Onset: Often gradual, but can be sudden, especially after an inciting event (e.g., surgery).

- Location: Usually asymmetrical (affecting one limb or side), though bilateral involvement is possible.

- Feeling of Heaviness/Fullness: The affected limb feels heavy, full, or tight, even before visible swelling is pronounced.

- "Stocking/Glove" Pattern: Swelling often starts distally (in the hand or foot) and progresses proximally up the limb, though this is not always the case.

- Reduced Pitting: Early on, the swelling may "pit." As the condition progresses and fibrosis occurs, it becomes less pitting or non-pitting.

- Skin Changes:

- Thickening and Hardening (Fibrosis): The skin and subcutaneous tissue become firm, tough, and rubbery.

- Peau d'Orange: The skin may take on an "orange peel" texture due to pitting around hair follicles.

- Hyperkeratosis: Thickening of the outer layer of the skin, leading to a rough, scaly, or wart-like appearance.

- Papillomatosis: Formation of small, wart-like growths on the skin surface.

- Skin Folds: Deepening of natural skin folds or the formation of new folds.

- Dryness and Cracking: The skin can become dry, flaky, and prone to cracking, increasing the risk of infection.

- Discoloration: The skin may appear pale, reddish, or brownish (hyperpigmentation) due to chronic inflammation or hemosiderin deposition.

- Discomfort and Functional Impairment:

- Pain/Aching: While often not severely painful, dull aching or discomfort is common, particularly in later stages or during inflammatory episodes.

- Tightness/Tension: A constant feeling of pressure or tightness in the affected area.

- Restricted Range of Motion: Swelling and tissue thickening can limit movement in joints.

- Difficulty with Clothing/Jewelry: Rings, watches, or clothing become tight or no longer fit.

- Impaired Function: Reduced ability to perform daily activities due to the size, weight, and stiffness of the limb.

- Numbness/Tingling: May occur due to nerve compression from swelling.

- Increased Susceptibility to Infection:

- Cellulitis: Recurrent bacterial infections (e.g., cellulitis, erysipelas) are a hallmark of lymphedema. Symptoms include redness, warmth, increased swelling, intense pain, fever, and malaise.

- Fungal Infections: The moist environment in skin folds makes fungal infections more common.

- Stemmer's Sign (Diagnostic Feature):

- A positive Stemmer's sign is often considered a hallmark of lymphedema in the toes or fingers. It is present when the skin at the base of the second toe (or middle finger) cannot be lifted into a fold. This indicates thickening and fibrosis of the skin and subcutaneous tissue. A negative Stemmer's sign (skin can be lifted) does not rule out lymphedema elsewhere in the limb.

- Stage 0 (Latency or Subclinical Lymphedema):

- Description: The lymphatic system is damaged, but there is no visible or palpable swelling. The transport capacity of the lymphatic system is impaired, but it can still manage the lymphatic load.

- Symptoms: Patients may report vague symptoms like occasional feelings of heaviness, fullness, or mild aching.

- Reversible: Potentially reversible with early intervention, or can remain at this stage for years.

- Stage 1 (Spontaneously Reversible Lymphedema):

- Description: Visible swelling is present. The edema is typically soft and pitting.

- Symptoms: Limb volume may increase. The swelling often reduces with limb elevation or overnight rest. Stemmer's sign may be negative or positive.

- Reversible: At this stage, the condition is largely reversible if effectively treated, as significant fibrotic changes have not yet occurred.

- Stage 2 (Spontaneously Irreversible Lymphedema):

- Description: The swelling is persistent and does not significantly reduce with elevation. The tissue texture begins to change, becoming firmer or "brawny" due to the accumulation of protein and the onset of fibrosis.

- Symptoms: The edema is less pitting or non-pitting. Stemmer's sign is typically positive. Skin changes (e.g., thickening, hyperkeratosis) may begin to appear.

- Irreversible: While the volume can be managed, the fibrotic changes make the tissue irreversible to complete normal appearance.

- Stage 3 (Lymphostatic Elephantiasis):

- Description: This is the most advanced and severe stage, characterized by significant and irreversible swelling, often referred to as "elephantiasis."

- Symptoms: Extreme increase in limb volume, gross tissue changes, extensive fibrosis, severe hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, deep skin folds, and often impaired mobility. Recurrent infections (cellulitis) are common. Lymphorrhea (leaking lymph fluid) may occur from skin lesions.

- Irreversible: Severe and debilitating, often with significant impact on quality of life.

The diagnosis of lymphedema is primarily clinical, based on a thorough history and physical examination. Imaging studies are often used to confirm the diagnosis, differentiate lymphedema from other edemas, and identify the underlying cause and lymphatic anatomy.

- Onset and Progression of Swelling: When did it start? Sudden or gradual? Unilateral or bilateral? Does it fluctuate? How has it changed?

- Medical History:

- Cancer Treatment: History of cancer, lymph node dissection, radiation therapy.

- Infections: History of recurrent cellulitis/erysipelas or parasitic infections.

- Trauma/Surgery: Previous injury or surgery to the affected region.

- Venous Disease: DVT or chronic venous insufficiency.

- Genetic Conditions: Family history.

- Symptoms: Heaviness, tightness, aching, skin changes, difficulty with clothing.

- Inspection: Asymmetry, Skin Changes (erythema, hyperpigmentation, hyperkeratosis), Hair Distribution (reduced/absent), Venous Patterns.

- Palpation: Temperature, Consistency (soft, pitting, firm, brawny), Stemmer's Sign.

- Measurements: Circumference Measurements, Volume Measurement (perometry, water displacement), Bioimpedance Spectroscopy (BIS).

| Modality | Procedure / Use | Findings in Lymphedema |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Lymphoscintigraphy (Radionuclide Lymphangioscintigraphy) |

|

Delayed or absent lymphatic uptake, visualization of collateral channels, dermal backflow (tracer remaining in skin), absence of lymph node visualization. |

| 2. Indocyanine Green (ICG) Lymphography | Fluorescent dye (ICG) injected intradermally and illuminated with near-infrared light. Visualizes superficial vessels. | Shows "dermal backflow," abnormal patterns ("splashes," "stardust"), and areas of obstruction. Useful for surgical planning. |

| 3. Magnetic Resonance Lymphangiography (MRL) | Uses MRI (with/without contrast) to visualize deeper lymphatic vessels and nodes. | Identifies vessel abnormalities, lymph node status, and differentiates lymphedema from other conditions. |

| 4. Ultrasonography (Ultrasound) | Primarily used to rule out DVT or cysts, and assess tissue thickness. | Increased subcutaneous tissue thickness, "honeycomb" patterns (dilated channels), thickening of dermis. |

| 5. CT Scan & MRI | Assess tumor involvement, quantify limb volume, differentiate from lipedema. | Show characteristic patterns of subcutaneous edema and thickening. |

- Chronic Venous Insufficiency (CVI): Often bilateral, varicose veins, skin discoloration (brawny), ulcers.

- Cardiac Edema (CHF): Bilateral, symmetrical, pitting, shortness of breath, JVD.

- Renal Edema: Bilateral, symmetrical, pitting, facial puffiness.

- Hepatic Edema: Ascites, jaundice, bilateral pitting edema.

- Hypothyroidism (Myxedema): Non-pitting edema.

- Lipedema: Chronic adipose disorder (mostly women), symmetrical, painful fat accumulation, feet spared, Stemmer's sign negative.

- Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT): Acute, unilateral, painful, warmth, redness.

The goal is to reduce swelling, prevent progression, manage symptoms, and improve quality of life. Treatment is primarily conservative.

The cornerstone of treatment. A two-phase program.

- Manual Lymphatic Drainage (MLD):

- Description: Gentle, rhythmic massage to stimulate flow and reroute lymph.

- Mechanism: Promotes lymphangiomotoricity and opens alternative pathways.

- Compression Bandaging:

- Description: Multiple layers of short-stretch bandages applied to the limb.

- Mechanism: Provides external pressure to reduce swelling, improve muscle pump efficiency, and break down fibrotic tissue. Worn 24 hours/day.

- Skin Care:

- Description: Meticulous hygiene and moisturizing.

- Mechanism: Prevents infection (cellulitis) in compromised skin.

- Decongestive Exercises:

- Description: Low-impact exercises worn with compression.

- Mechanism: Activates muscle pump to move fluid.

- Education: Self-care techniques and infection prevention.

- Compression Garments: Custom-fitted or ready-to-wear garments worn daily. Replace bandages once volume is stabilized.

- Self-MLD: Patients taught simplified techniques.

- Self-Bandaging: Applied at night or during flare-ups.

- Regular Exercise & Lifelong Skin Care.

- Regular Follow-ups.

- Pneumatic Compression Pumps: Devices applying sequential pressure. Adjunct to CDT.

- Weight Management: Crucial for obese patients to reduce mechanical compression on vessels.

- Lymphaticovenous Anastomosis (LVA) / Bypass (LVB):

- Description: Microsurgical connection of lymphatic vessels to small veins.

- Mechanism: Bypasses obstruction by draining into venous system.

- Indication: Early to moderate lymphedema.

- Vascularized Lymph Node Transfer (VLNT):

- Description: Transplantation of healthy lymph nodes to the affected area.

- Mechanism: Provides new drainage pathways and growth factors.

- Direct Excision/Debulking: Surgical removal of excess fibrotic tissue. For very advanced/disfigured limbs.

- Liposuction (Suction-Assisted Lipectomy):

- Description: Removal of excess adipose tissue.

- Indication: Chronic Stage 2 or 3 where maximal decongestion is achieved but fat remains. Requires lifelong compression post-op.

- Related to: Edema, altered circulation, chronic inflammation, skin changes.

- As evidenced by: Swelling, thickened skin, discoloration, fissures, positive Stemmer's sign.

- Interventions:

- Assess skin integrity daily: Inspect for redness, warmth, cracks, blisters, signs of infection.

- Provide meticulous skin care: Wash daily with mild soap, pat dry (especially folds). Apply low pH, non-perfumed moisturizer.

- Protect skin from injury: Wear gloves for chores, use electric razor, avoid tight clothing/jewelry.

- Elevate affected limb when resting.

- Implement wound care protocols for breakdown.

- Ensure proper fit of compression garments to prevent irritation.

- Related to: Accumulation of protein-rich fluid (bacterial medium), altered skin integrity, decreased local immune response.

- Interventions:

- Educate on signs of infection: Redness, warmth, increased swelling, pain, fever, streaks. Report immediately.

- Emphasize strict skin care regimen.

- Advise on avoiding trauma: Prevent cuts, insect bites, sunburns, needle sticks (no blood draws/BP in affected limb).

- Discuss prophylactic antibiotics if history of recurrent cellulitis.

- Encourage prompt treatment of minor cuts with antiseptic.

- Related to: Tissue distension, nerve compression, fibrosis, heavy limb.

- Interventions:

- Assess pain characteristics.

- Administer prescribed analgesics.

- Implement non-pharmacological strategies: Elevation, cold/warm packs (caution with sensation), gentle massage, relaxation.

- Ensure proper fit of compression garments to avoid constriction.

- Encourage gentle exercises to reduce stiffness.

- Related to: Increased limb size/weight, stiffness, fear of injury.

- Interventions:

- Assess mobility and ROM.

- Encourage gentle active/passive ROM exercises.

- Collaborate with PT/OT for tailored programs.

- Instruct on proper body mechanics.

- Related to: Limb disfigurement, clothing difficulties.

- Interventions:

- Provide safe environment to express feelings.

- Listen actively and empathetically.

- Focus on functional improvements rather than just cosmetic.

- Suggest coping strategies: Clothing choices, support groups, counseling.

- Related to: Complexity of treatment, lack of information, barriers to adherence.

- Interventions:

- Assess current knowledge and learning style.

- Provide clear education on: MLD, compression, skin care, infection prevention, signs of complications.

- Use teach-back method.

- Provide written materials/videos.

- Address barriers (cost, time).

- Refer to Certified Lymphedema Therapist (CLT).

- Certified Lymphedema Therapist (CLT): Essential for CDT implementation.

- Physician/Specialist: Diagnosis and medical management.

- PT/OT: Functional adaptations.

- Dietitian: Weight management.

- Social Worker/Psychologist: Emotional support.