Table of Contents

ToggleGANGRENE

Definition

Causes: Ischemia and Infection as Primary Drivers

- Thrombosis: Formation of a blood clot within a blood vessel, obstructing flow.

- Embolism: A piece of clot, fat, or other material travels and lodges in a blood vessel, blocking it.

- Atherosclerosis: Hardening and narrowing of arteries, leading to chronic reduction in blood flow, especially to the extremities.

- Vasoconstriction/Vasospasm: Severe narrowing of blood vessels (e.g., in Raynaud's phenomenon).

- External Compression: Pressure on blood vessels (e.g., from tight casts, prolonged immobility leading to pressure ulcers).

- Gas Gangrene: Caused predominantly by *Clostridium perfringens* and other anaerobic bacteria, which produce potent toxins and gas within tissues.

- Streptococcal and Staphylococcal Infections: While less common as a primary cause of widespread gangrene compared to clostridial species, severe invasive infections (e.g., necrotizing fasciitis) can rapidly lead to tissue death.

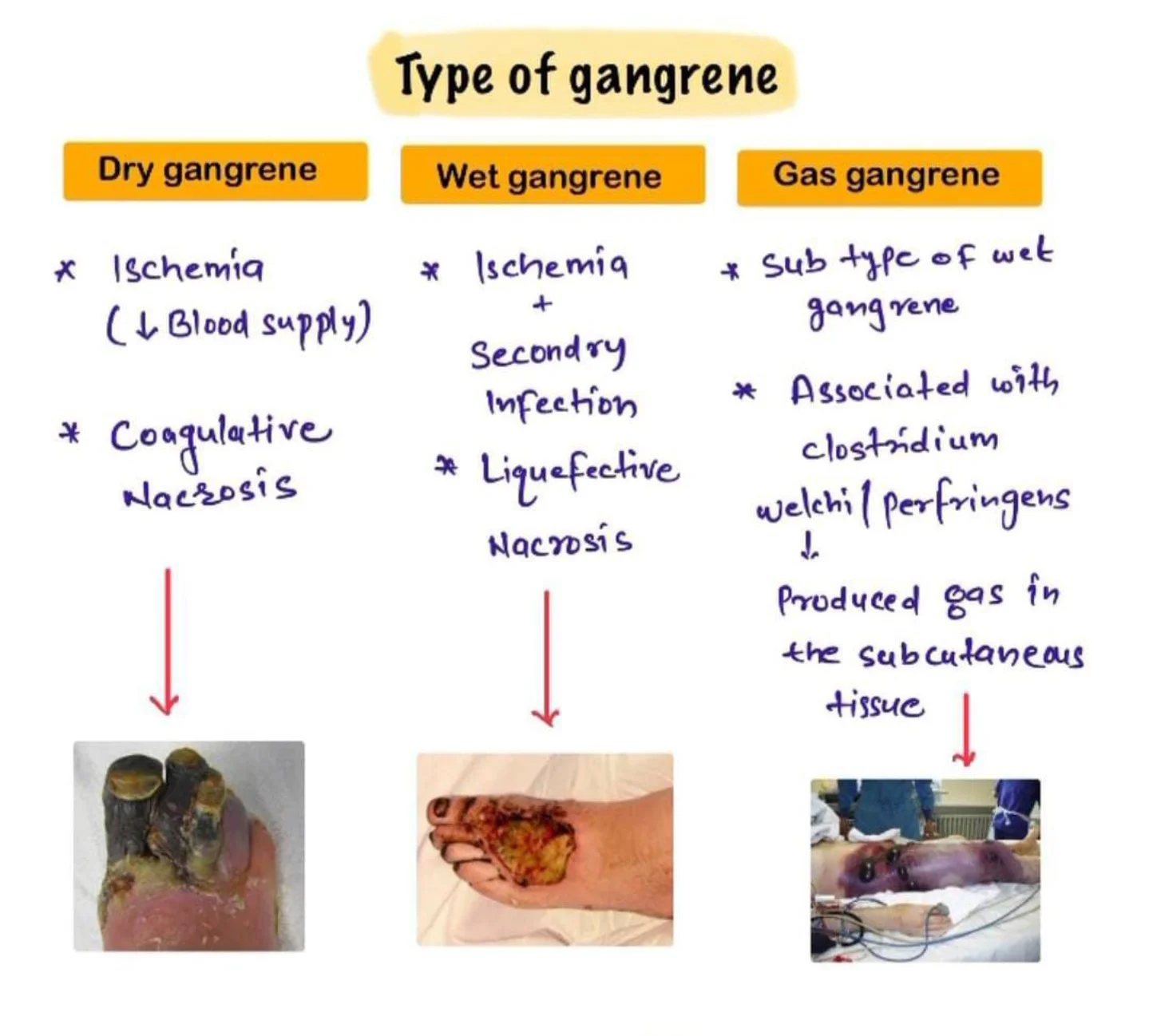

Types of Gangrene

Dry Gangrene

- Dry gangrene begins at the distal part of the limb due to ischemia and often occurs in the toes and feet of elderly patients due to arteriosclerosis (abnormal thickening and hardening of the arterial walls).

- Dry gangrene spreads slowly until it reaches the point where the blood supply is inadequate to keep tissue viable.

- The affected part is dry, shrunken and dark black, resembling mummified flesh.

- If the blood flow is interrupted for a reason other than severe bacterial infection, the result is a case of dry gangrene.

- People with impaired peripheral blood flow, such as diabetics, are at greater risk of contracting dry gangrene.

- The early signs are a dull ache and sensation of coldness in the affected area.

- If caught early, the process can sometimes be reversed by vascular surgery.

- If necrosis sets in, the affected tissue must be removed and treated like a case of wet gangrene.

Wet Gangrene

- Wet gangrene occurs in naturally moist tissue and organs such as the mouth, bowel, lungs, cervix, and vulva.

- Bedsores occurring on body parts such as the sacrum, buttocks and heels (not in “moist” areas) are also categorized as wet gangrene infections.

- In wet gangrene, the tissue is infected by microorganisms, which cause tissue to swell and emit a foul odour.

- Wet gangrene usually develops rapidly due to blockage of venous and/or arterial blood flow.

- The affected part is saturated with stagnant blood which promotes the rapid growth of bacteria.

- The toxic products formed by bacteria are absorbed causing systemic manifestation of bacteria and finally death.

- The affected part is soft, putrid, rotten and dark.

- The darkness in wet gangrene occurs due to the same mechanism as in dry gangrene.

Gas Gangrene

- Gas gangrene is a bacterial infection that produces gas within tissues.

- It is a deadly form of gangrene usually caused by bacteria.

- Infection spreads rapidly as the gases produced by bacteria expand and effect healthy tissue.

- Gas gangrene is caused by environmental bacteria; Clostridium perfringens.

- It can also be from; Group A Streptococcus, Staphylococcus aureus & Vibrio vulnificus.

- These Bacteria are mostly found in soil.

- These environmental bacteria enter the muscle through a wound and cause necrotic tissue and powerful toxins.

- These toxins destroy nearby tissue, generating gas at the same time.

- Gas gangrene can cause necrosis, gas production, and sepsis.

- Progression to toxemia and shock is often very rapid.

- Because of its ability to quickly spread to surrounding tissues, gas gangrene should be treated as a medical emergency.

Internal Gangrene

- Strangulated Hernia: A loop of intestine becomes trapped and its blood supply is cut off.

- Volvulus: Twisting of the intestine.

- Intussusception: A portion of the intestine telescopes into another.

- Ischemic Colitis: Reduced blood flow to the colon.

- Acute Mesenteric Ischemia: Blockage of major arteries supplying the intestines.

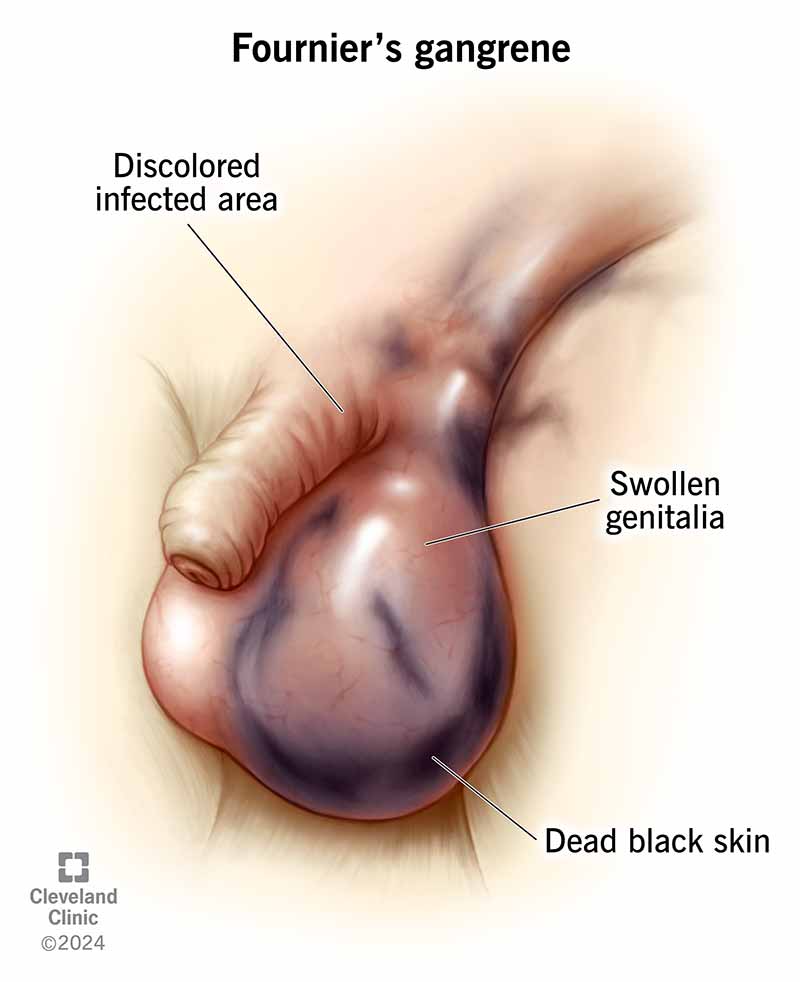

Fournier's Gangrene

Meleney's Gangrene (Progressive Bacterial Synergistic Gangrene)

- Description: A rare, chronic, and progressively spreading necrotizing soft tissue infection, often occurring as a complication of surgery (especially abdominal surgery) or trauma.

- Etiology: Caused by a synergistic infection, typically involving a microaerophilic non-hemolytic Streptococcus and a Staphylococcus aureus.

- Clinical Presentation: Patients develop exquisitely painful, rapidly enlarging skin lesions, often one to two weeks after an operation. The lesion has a characteristic appearance: a central area of necrosis and ulceration surrounded by a purplish zone, which is then surrounded by an outer ring of erythema.

- Management: Requires aggressive debridement and targeted antibiotic therapy.

Risk Factors & Clinical Picture: Who is at Risk and What to Look For

General Risk Factors for Gangrene Development

Any condition that impairs blood flow, compromises the immune system, or increases susceptibility to severe infections can elevate the risk of gangrene.

- Atherosclerosis: Hardening and narrowing of arteries, leading to Peripheral Arterial Disease (PAD).

- Peripheral Arterial Disease (PAD): Critical reduction of blood flow to the limbs.

- Raynaud's Phenomenon: Severe vasoconstriction in fingers and toes, though typically not severe enough to cause gangrene unless prolonged and severe.

- Severe Vasculitis: Inflammation of blood vessels.

- Diabetes Mellitus: A leading cause. Imbalanced blood sugar levels damage blood vessels (micro- and macroangiopathy) and nerves (neuropathy), reducing sensation and blood flow, making feet especially vulnerable to injury and infection.

- Smoking: Significantly damages blood vessels, accelerates atherosclerosis, and reduces oxygen delivery to tissues.

- Obesity: Contributes to diabetes and vascular disease.

- Alcoholism: Can lead to malnutrition and a weakened immune system.

- Intravenous Drug Use (IVDU): Can cause local infections, abscesses, and damage to blood vessels at injection sites.

- Weak Immune System: Conditions like HIV/AIDS, cancer, chemotherapy, or long-term corticosteroid use impair the body's ability to fight infection.

- Serious Injury or Trauma: Crush injuries, deep penetrating wounds, frostbite, severe burns, and scalds can directly damage tissues and blood vessels, leading to ischemia and providing entry points for bacteria.

- Surgery: While rare, can introduce bacteria or compromise blood supply if not managed carefully.

- Direct infection by highly virulent bacteria (e.g., *Clostridium perfringens*, Group A Streptococcus) can cause gangrene even in initially healthy tissue, particularly in necrotizing fasciitis.

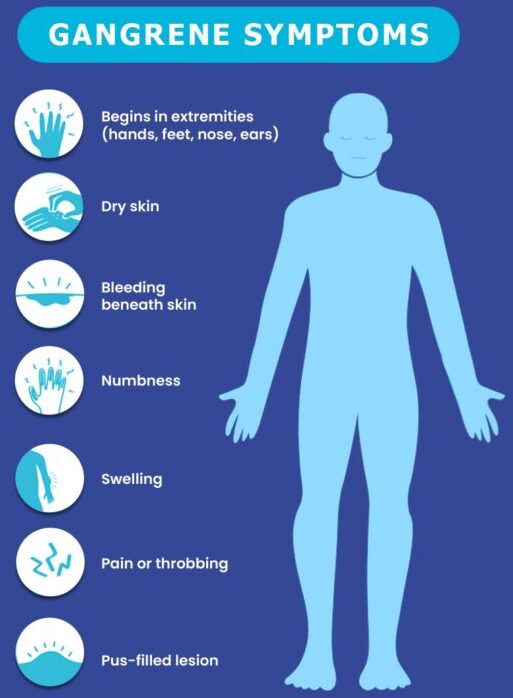

Signs and Symptoms: Recognizing the Clinical Presentation

Symptoms typically begin suddenly and can worsen rapidly, especially in wet or gas gangrene. Clinical presentation varies by type but generally includes:

- Pain: Moderate to severe pain, which can be disproportionate to the visible injury (especially in gas gangrene or necrotizing fasciitis). Pain may initially be dull or aching, progressing to intense, throbbing, or burning.

- Skin Discoloration:

- Dry Gangrene: Initial pallor, progressing to dull red, purple, then ultimately black, resembling mummified tissue.

- Wet/Gas Gangrene: Initial pallor or bronze discoloration, rapidly progressing to dark red, purplish, or black.

- Swelling (Edema): Progressive and often rapid swelling around the affected area. The tissue may feel tense and firm.

- Blisters/Bullae: Formation of vesicles or large bullae (blisters) filled with brown, foul-smelling, or serosanguineous (blood-tinged) fluid.

- Foul Odor: A putrid, sweetish, mousy, or decaying smell emanating from the affected tissue, particularly in wet and gas gangrene due to bacterial activity.

- Skin Breakdown: Ulceration, sloughing of skin, and visible decay.

- Crepitus: A palpable crackling or crunching sensation when the affected area is pressed, indicating the presence of gas in the subcutaneous tissues (a hallmark of gas gangrene).

- Fever: Moderate to high-grade fever, often accompanied by chills and rigors.

- Tachycardia: Rapid heart rate.

- Tachypnea: Rapid breathing.

- Hypotension: Low blood pressure, especially as sepsis progresses to septic shock.

- Diaphoresis: Profuse sweating.

- Altered Mental Status: Confusion, disorientation, stupor, or delirium, progressing to coma in severe cases.

- Oliguria/Anuria: Decreased or absent urine output due to kidney injury.

- Nausea, Vomiting, Abdominal Pain: If internal organs are affected.

- General Malaise: Feeling unwell, weakness, fatigue.

Diagnostics: Confirming the Diagnosis and Guiding Treatment

Diagnosis of gangrene is primarily clinical, but diagnostic tests are crucial for confirming the type, identifying the causative organism, assessing the extent of tissue damage, and guiding treatment.

- Complete Blood Count (CBC): Marked leukocytosis (elevated white blood cell count) with a left shift is typical, indicating bacterial infection. Anemia may also be present.

- Inflammatory Markers: Elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). Procalcitonin levels can also be useful in assessing the severity of bacterial infection.

- Blood Cultures: To identify bacteremia and systemic infection. Crucial for guiding systemic antibiotic therapy.

- Electrolytes, Renal Function Tests (BUN, Creatinine): To assess for fluid and electrolyte imbalances and kidney injury, especially with sepsis.

- Liver Function Tests (LFTs): To assess for liver involvement.

- Blood Glucose: Especially important for diabetic patients to assess control.

- Gram Stain of Fluid/Tissue Aspirate: Rapid identification of bacterial morphology (e.g., Gram-positive rods suggestive of Clostridium).

- Aerobic and Anaerobic Tissue/Fluid Culture and Sensitivity: Definitive identification of causative organisms and their susceptibility to antibiotics. This is critical for targeted therapy.

- Plain X-rays: Can reveal gas in soft tissues (subcutaneous emphysema), especially useful for suspected gas gangrene. May also show foreign bodies or underlying bone involvement (osteomyelitis).

- Ultrasound: Can show fluid collections, tissue edema, and sometimes gas. Also useful for assessing blood flow (Doppler ultrasound).

- Computed Tomography (CT) Scan: Provides detailed cross-sectional images, clearly delineating the extent of soft tissue involvement, fascial plane involvement, and the presence and distribution of gas. Essential for pre-surgical planning.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): Offers superior soft tissue contrast, invaluable for assessing muscle involvement, edema, and differentiating between viable and non-viable tissue. Can be particularly useful for identifying necrotizing fasciitis early.

- Angiography (CT Angiography, MR Angiography, Conventional Angiography): To visualize arterial blood flow and identify blockages in cases of suspected dry gangrene or critical limb ischemia, guiding revascularization procedures.

Management of Gangrene

Managing necrotizing infections like gangrene requires a multi-faceted approach, integrating medical, surgical, and comprehensive nursing interventions. Historically, methods like maggot therapy (biodebridement) were used for necrotic tissue. While largely superseded by antibiotics, maggot therapy has seen a resurgence in specific chronic wound care cases due to its efficacy in consuming only devitalized tissue.

I. Medical & Surgical Management (Collaborative Care)

A. On Admission & Initial Assessment:

- Patient Placement: Admit to a surgical ward; consider isolation precautions (e.g., contact precautions) if the infection is highly virulent or there's significant exudate/drainage. Barrier nursing principles are paramount to prevent cross-contamination.

- Positioning: Position the patient for comfort and to optimize circulation to unaffected areas. Elevate affected limbs if swelling is present, unless contraindicated by arterial insufficiency. Frequent repositioning is essential to prevent pressure injuries.

- Vital Signs & General Observation: Obtain and meticulously record baseline vital signs (temperature, pulse, respiration, blood pressure, oxygen saturation). Observe for signs of systemic infection (JACCOLD: Jaundice, Anemia, Cyanosis, Clubbing, Oedema, Lymphadenopathy, Dehydration – though for acute infection, focus more on fever, tachycardia, tachypnea, hypotension, altered mental status). Assess for signs of sepsis and septic shock.

- Intravenous Access: Establish immediate IV access for fluid resuscitation, antibiotic administration, and other necessary medications, according to physician's orders.

- Pain Assessment: Perform a comprehensive pain assessment using an appropriate pain scale.

B. Investigations:

Prompt diagnostic testing is crucial for identifying the causative organism and assessing the extent of systemic involvement.

- Wound Culture & Sensitivity: Aspirate fluid or tissue from the wound for Gram stain, aerobic and anaerobic culture, and sensitivity testing to guide targeted antibiotic therapy.

- Blood Cultures: Obtain blood cultures (typically two sets from different sites) to identify bacteremia and potential sepsis.

- Imaging Studies:

- X-ray: To determine the presence of gas (crepitus/bubbles) in soft tissues (suggestive of gas gangrene) or bone involvement (osteomyelitis).

- CT/MRI: Provide more detailed visualization of soft tissue involvement, extent of necrosis, and gas patterns.

- Hematological Studies:

- Complete Blood Count (CBC): To assess for leukocytosis (elevated WBC count, indicating infection), anemia (due to chronic disease or blood loss), and platelet count.

- Coagulation Profile (PT/INR, PTT): To assess clotting status, especially in severe sepsis or disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC).

- C-Reactive Protein (CRP) & Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR): Inflammatory markers indicating systemic inflammation.

- Biochemical Studies:

- Electrolytes, Renal Function Tests (BUN, Creatinine): To monitor for fluid and electrolyte imbalances and assess kidney function, especially with antibiotic use or sepsis.

- Liver Function Tests (LFTs): To assess for liver involvement/damage.

- Blood Glucose: Especially important for diabetic patients, as hyperglycemia can worsen infections.

- Type & Crossmatch: Prepare for potential blood transfusions to correct anemia or support hemodynamic stability, especially in severe cases or impending surgery.

C. Treatment (Pharmacological & Surgical):

- Antibiotic Therapy:

- Administer broad-spectrum antibiotics intravenously immediately after cultures are drawn, without waiting for results. Examples include high-dose penicillin (e.g., Penicillin G 2.4 million units IV q4-6h) for clostridial infections, along with synergistic agents like clindamycin to inhibit toxin production.

- Cephalosporins (e.g., ceftriaxone), fluoroquinolones (e.g., ciprofloxacin), and metronidazole (for anaerobic coverage, typically 500mg IV q6-8h) are often part of combination therapy, tailored to suspected pathogens.

- Antibiotics alone are often insufficient because they may not adequately penetrate ischemic or necrotic muscles.

- Antitoxins: In specific cases (e.g., gas gangrene caused by *Clostridium perfringens*), antitoxin administration may be considered, though its efficacy is debated and it's less commonly used than antibiotics.

- Analgesia: Aggressive pain management is crucial. Administer analgesics as prescribed, such as diclofenac 75mg IM, or opioids like tramadol IV or IM, titrated to effect. Consider patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) for severe pain.

- Blood Transfusion: Administer packed red blood cells as indicated to correct anemia and improve oxygen-carrying capacity, especially in hemodynamically unstable patients.

- Surgical Intervention:

- Emergent Debridement: The most critical intervention. Surgical debridement to remove all necrotic, infected tissue is often life-saving. This involves extensive incision and drainage to establish a larger wound opening for aeration (as many causative bacteria are anaerobic) and promote drainage. Repeat debridements may be necessary.

- Amputation: If the limb is extensively gangrenous, non-viable, or threatening the patient's life due to uncontrolled infection, amputation (surgical removal of the limb) may be necessary to prevent further spread and save the patient's life.

- Revascularization: For arterial gangrene, restoring blood flow to the affected area (e.g., bypass surgery, angioplasty) is the best treatment option, as it addresses the underlying ischemia. This may precede or follow debridement depending on the clinical situation.

- Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy (HBOT): Administration of 100% oxygen at increased atmospheric pressure. This can inhibit the growth of anaerobic bacteria, enhance the killing power of phagocytes, and promote angiogenesis and wound healing. It's often used as an adjunctive therapy, particularly in gas gangrene.

II. Nursing Diagnoses & Interventions

A. Impaired Tissue Integrity (Related to necrotic tissue, infection, impaired circulation)

- Wound Care & Debridement Assistance:

- Assist physician/surgeon with debridement procedures (surgical, mechanical, enzymatic, autolytic).

- Perform meticulous wound care with strict aseptic technique (medical and surgical asepsis). Ensure all equipment and linens are autoclaved and sterile.

- Irrigate wounds as prescribed (e.g., with normal saline, hydrogen peroxide for specific anaerobic infections).

- Apply prescribed dressings (e.g., moist-to-dry, specialized antimicrobial dressings, negative pressure wound therapy [NPWT]).

- Observe the wound closely for bleeding, oozing, increased exudate, foul odor, changes in color, and signs of spreading infection (e.g., cellulitis, crepitus). Document findings thoroughly.

- Monitor drainage and secretions. Implement appropriate isolation precautions (e.g., contact precautions) based on institutional policy and pathogen.

- Educate patient and family on proper hand hygiene and avoiding contamination of the wound.

- Circulatory Management:

- Elevate affected limb if edema is present (unless contraindicated by arterial disease) to promote venous return.

- Assess peripheral pulses, capillary refill, skin color, and temperature regularly in the affected and unaffected limbs.

- Avoid restrictive clothing or bedding that could impede circulation.

- Nutritional Support: Ensure adequate protein, calorie, vitamin (especially C and A), and mineral (zinc) intake to promote wound healing. Consult with a dietitian.

B. Acute Pain (Related to tissue damage, surgical incisions, infection)

- Pain Assessment & Management:

- Regularly assess pain intensity, characteristics, and location using an appropriate pain scale (e.g., 0-10 numeric scale).

- Administer prescribed analgesics proactively and on a schedule, rather than waiting for severe pain. Utilize a multimodal approach (e.g., opioids, NSAIDs, adjuncts).

- Evaluate the effectiveness of pain medication and adjust as needed in collaboration with the physician.

- Teach and encourage non-pharmacological pain relief methods (e.g., relaxation techniques, guided imagery, distraction, repositioning, application of heat/cold if appropriate and safe).

- Comfort Measures:

- Ensure patient is in a comfortable position, using pillows for support.

- Maintain a quiet and calming environment. Minimize unnecessary disturbances.

C. Risk for Infection / Sepsis (Related to invasive procedures, compromised immune status, necrotic tissue)

- Infection Control:

- Adhere to strict hand hygiene before and after all patient contact and procedures.

- Maintain sterile technique for all invasive procedures (e.g., dressing changes, IV insertion, catheterization).

- Monitor for signs of systemic infection (fever, chills, tachycardia, hypotension, altered mental status, increased WBC count).

- Administer prescribed antibiotics on time and monitor for adverse effects.

- Maintain meticulous Foley catheter care (if applicable) to prevent urinary tract infections.

- Ensure proper care of all IV lines to prevent phlebitis or line infections.

- Fluid & Electrolyte Balance: Monitor intake and output, urine specific gravity, and electrolyte levels. Administer IV fluids as prescribed to maintain hydration and perfusion.

- Early Ambulation: Encourage early mobilization as tolerated to prevent complications like pneumonia and deep vein thrombosis (DVT), which can worsen systemic compromise.

D. Disturbed Sleep Pattern (Related to pain, hospital environment, anxiety)

- Environmental Modifications:

- Optimize sleep environment: dim lights, control noise on the ward (e.g., wear soft-soled shoes, lower voices, prompt treatment of alarms).

- Bundle nursing care to minimize nighttime interruptions.

- Comfort & Relaxation:

- Administer pain medication before sleep if pain is a factor.

- Offer warm beverages (if allowed), back rubs, or a quiet conversation.

- Suggest relaxation techniques or play soft, calming music for those who find it helpful.

- Daytime Activities: Encourage appropriate daytime activity and exposure to natural light to help regulate circadian rhythm.

E. Self-Care Deficit (Related to pain, weakness, impaired mobility)

- Hygiene & Personal Care:

- Assist with daily bed baths or showers as tolerated. Maintain personal hygiene.

- Perform oral care at least twice daily, or more frequently if patient is NPO or has a dry mouth.

- Provide meticulous skin care, especially for pressure areas, by repositioning every 2 hours and using pressure-relieving devices.

- Elimination: Ensure regular bowel and bladder elimination. Offer bedpan/urinal frequently or assist to commode/bathroom as mobility allows. Monitor for constipation or urinary retention.

- Encourage Independence: Promote patient independence in self-care activities as much as possible to foster a sense of control and recovery.

III. Long-Term Management & Discharge Planning

A. Patient Education:

Comprehensive patient and family education is vital for successful recovery and prevention of recurrence.

- Medication Compliance: Emphasize the importance of completing the full course of antibiotics, even if symptoms improve, to prevent antibiotic resistance and recurrence.

- Wound Care at Home: Provide clear, step-by-step instructions (and demonstration) on wound care, dressing changes, and signs of infection to report immediately.

- Activity Restrictions: Explain any activity restrictions or limitations on the affected limb/area.

- Nutrition: Reinforce the importance of a balanced diet to support healing.

- Recognition of Complications: Educate on signs and symptoms of potential complications (e.g., worsening infection, fever, increasing pain, changes in wound, signs of sepsis) and when to seek immediate medical attention.

- Lifestyle Modifications: Discuss management of underlying conditions (e.g., strict glycemic control for diabetics, smoking cessation for PVD).

B. Follow-up Care:

- Schedule follow-up appointments with the surgeon, wound care specialist, and primary care provider.

- Arrange for home health nursing services if indicated for complex wound care or continued monitoring.

- Provide contact information for emergencies and questions.

IV. Potential Complications

Close monitoring for and prompt intervention against complications are essential for positive patient outcomes.

- Disfiguring or disabling, permanent tissue damage (e.g., loss of limb function, scarring).

- Osteomyelitis (bone infection).

- Recurrence of infection.

- Sepsis: Life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection.

- Septic Shock: Sepsis with persistent hypotension requiring vasopressors and elevated lactate.

- Acute Kidney Injury/Failure (due to sepsis or nephrotoxic medications).

- Liver damage/Jaundice (due to sepsis, severe infection, or certain medications).

- Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation (DIC).

- Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS).

- Stupor

- Delirium

- Coma

- Chronic pain.

- Impaired mobility and functional limitations requiring rehabilitation.

- Psychological distress (anxiety, depression, body image issues).

Good work