Respiratory Distress Syndrome (RDS), also known as Hyaline Membrane Disease (HMD), is a common and often severe lung disorder primarily affecting premature newborns. It is characterized by progressive respiratory failure that develops shortly after birth, typically within the first few hours of life.

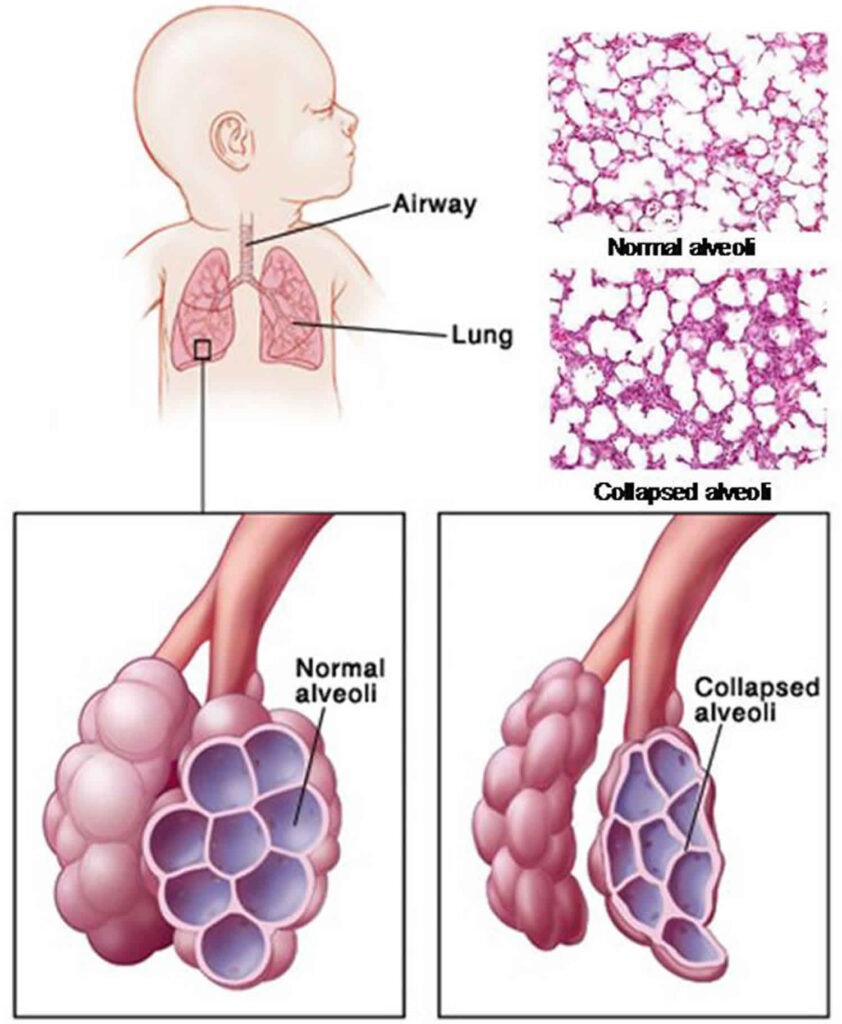

The hallmark of RDS is a deficiency in pulmonary surfactant and structural immaturity of the lungs, leading to widespread atelectasis (collapse of the alveoli) and impaired gas exchange.

The problem in RDS revolves around two main factors: surfactant deficiency and structural immaturity of the lungs.

- What is Surfactant?

- Pulmonary surfactant is a complex mixture of lipids (about 90%) and proteins (about 10%) produced by specialized cells in the lungs called Type II pneumocytes (also known as Type II alveolar cells).

- The primary lipid component is dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine (DPPC), which is crucial for its function.

- Surfactant production typically begins around 24-28 weeks of gestation but does not reach sufficient levels to prevent RDS until approximately 34-36 weeks of gestation.

- Function of Surfactant:

- Reduces Surface Tension: The most critical function of surfactant is to lower the surface tension at the air-liquid interface within the alveoli.

- Prevents Alveolar Collapse (Atelectasis): Without adequate surfactant, the high surface tension causes the small, fragile alveoli to collapse at the end of expiration. This requires a much greater effort to re-open them with each subsequent breath.

- Maintains Functional Residual Capacity (FRC): Surfactant helps keep the alveoli partially open even after exhalation, maintaining a volume of air in the lungs that allows for continuous gas exchange.

- Promotes Alveolar Stability: It ensures uniform inflation of alveoli of different sizes, preventing smaller alveoli from collapsing into larger ones.

- How Surfactant Deficiency Leads to Impaired Gas Exchange:

- Increased Work of Breathing: With deficient surfactant, the infant must exert tremendous effort (high negative intrathoracic pressure) to open collapsed alveoli with each breath. This leads to respiratory muscle fatigue and distress.

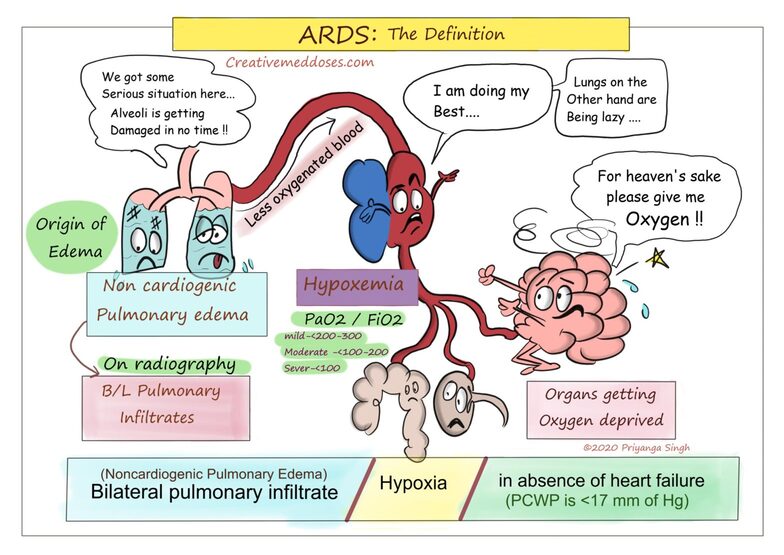

- Widespread Atelectasis: Many alveoli remain collapsed, reducing the functional lung volume available for gas exchange.

- Ventilation-Perfusion (V/Q) Mismatch: Blood continues to flow past collapsed or poorly ventilated alveoli. This creates a V/Q mismatch, where blood is shunted through the lungs without picking up oxygen, leading to hypoxemia (low blood oxygen).

- Carbon Dioxide Retention: Inadequate ventilation also leads to impaired removal of carbon dioxide, resulting in hypercapnia (high blood carbon dioxide).

- Acidosis: The combination of hypoxemia and hypercapnia, coupled with increased metabolic demands due to the work of breathing, leads to metabolic and respiratory acidosis.

- Pulmonary Vasoconstriction: Hypoxemia and acidosis cause pulmonary vasoconstriction, increasing pulmonary vascular resistance. This can lead to persistent fetal circulation (right-to-left shunting) through the foramen ovale and patent ductus arteriosus, further exacerbating hypoxemia.

- Alveolar Damage and Hyaline Membrane Formation: The repeated collapse and re-expansion of alveoli, combined with pulmonary edema and inflammation, can damage the alveolar lining cells. Plasma proteins and necrotic cellular debris leak into the alveoli, forming a fibrin-rich exudate known as hyaline membranes. These membranes further impede gas exchange, hence the alternative name "Hyaline Membrane Disease."

- Immature Alveoli: In premature infants, the lungs are not fully developed. The saccules (precursors to alveoli) are fewer in number, larger, and have thicker walls than mature alveoli. This reduces the surface area available for gas exchange.

- Immature Capillary Bed: The pulmonary capillary network surrounding the alveoli may also be underdeveloped, hindering efficient oxygen and carbon dioxide transfer across the alveolar-capillary membrane.

- Fragile Lung Tissue: Premature lung tissue is more fragile and susceptible to injury from mechanical ventilation or inflammation.

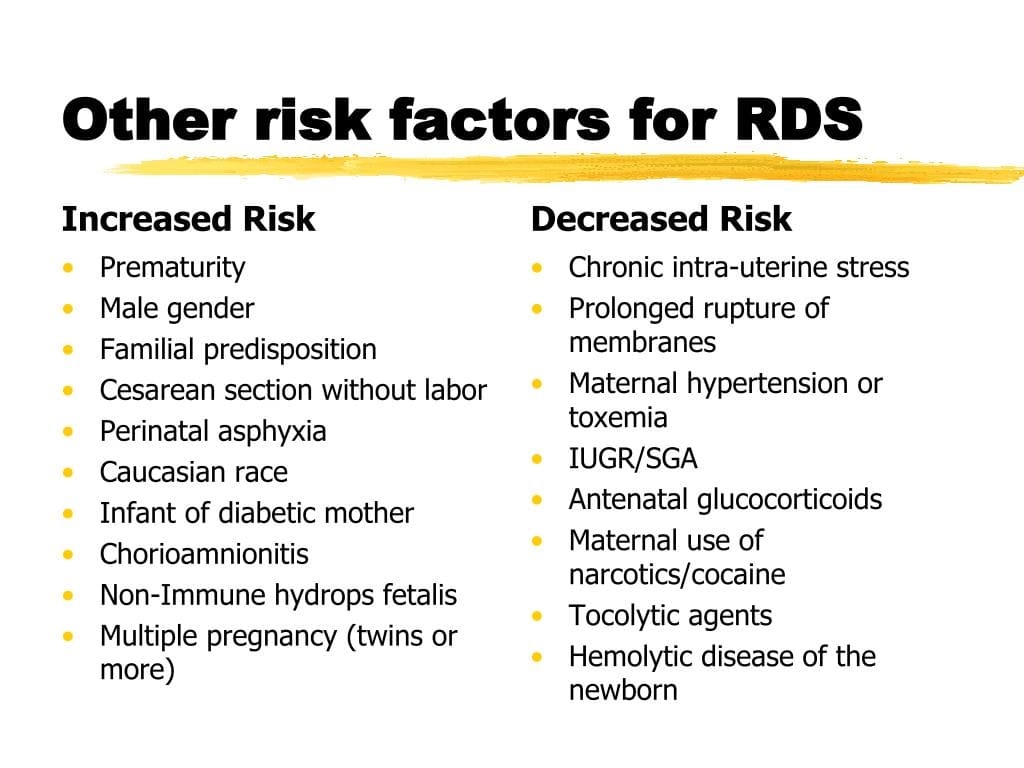

While RDS is primarily a disease of prematurity due to insufficient surfactant production, certain factors can either increase the likelihood of its development or worsen its severity.

- Risk Profile:

- < 28 weeks gestation: Almost all infants will develop RDS.

- 28-32 weeks gestation: High risk, but incidence decreases with increasing gestational age.

- 32-36 weeks gestation: Moderate risk, incidence continues to decrease.

- 37 weeks gestation: RDS is rare, but can occur in specific circumstances (see below).

These are conditions in the mother that can either predispose the fetus to premature birth or directly affect fetal lung maturity.

These are factors related to the baby's health or the circumstances of delivery that can influence lung maturity or function.

RDS presents within the first few hours of life, often immediately after birth, with a progressive worsening of respiratory effort. The signs are those of generalized respiratory distress.

- Tachypnea: Abnormally rapid breathing rate (typically > 60 breaths per minute in a newborn). This is often the earliest sign as the infant attempts to compensate for poor gas exchange.

- Mechanism: Increased respiratory drive to improve ventilation and oxygenation.

- Expiratory Grunting: A short, low-pitched sound heard during expiration.

- Mechanism: The infant attempts to maintain lung volume (functional residual capacity) by exhaling against a partially closed glottis. This creates back-pressure that prevents complete alveolar collapse. It's an auto-PEEP (Positive End-Expiratory Pressure) mechanism.

- Nasal Flaring: Widening of the nostrils during inspiration.

- Mechanism: Increases the diameter of the nasal passages, thereby reducing airway resistance and making it easier to inhale air.

- Retractions (Indrawing): Visible pulling in of the skin and soft tissues of the chest wall during inspiration. These can be:

- Subcostal: Below the ribs.

- Intercostal: Between the ribs.

- Substernal: Below the sternum.

- Suprasternal/Supraclavicular: Above the sternum or collarbones (indicating more severe distress).

- Mechanism: Due to increased negative intrathoracic pressure generated during forceful inspiration as the infant struggles to inflate stiff, non-compliant lungs.

- Cyanosis: Bluish discoloration of the skin, mucous membranes, and nail beds. Can be central (affecting lips, tongue, trunk) or peripheral (affecting hands and feet, which is less indicative of severe hypoxia).

- Mechanism: Insufficient oxygenation of arterial blood (hypoxemia), leading to a higher concentration of deoxygenated hemoglobin. Requires significant hypoxemia to be clinically apparent. Often masked by supplemental oxygen.

- Decreased Breath Sounds: Due to poor air entry into atelectatic lung areas.

- Pallor: Pale skin, often indicating poor perfusion, anemia, or hypothermia.

- Hypotonia/Lethargy: As distress worsens and hypoxemia/acidosis become severe.

- Apnea: Cessation of breathing, a sign of severe respiratory fatigue or central nervous system depression.

The diagnosis of RDS is a clinical one, supported by specific investigations.

As described above: onset of characteristic signs of respiratory distress (tachypnea, grunting, flaring, retractions) typically within the first few hours of life in a premature infant. The distress usually worsens over the first 48-72 hours if untreated.

- Reticulogranular (Ground Glass) Pattern: Fine, diffuse granular opacities throughout both lung fields. This represents widespread micro-atelectasis (collapsed alveoli) and diffuse alveolar edema.

- Air Bronchograms: Lucent (darker, air-filled) branching structures (bronchi) visible against the opaque (whiter, fluid-filled or collapsed) lung parenchyma. This indicates that the larger airways are open while the surrounding alveoli are filled with fluid or collapsed.

- Decreased Lung Volumes: Small, under-inflated lung fields, indicating poor expansion.

- Hypoxemia: Decreased PaO2 (partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood), often requiring supplemental oxygen to maintain adequate saturation.

- Hypercapnia: Increased PaCO2 (partial pressure of carbon dioxide in arterial blood), indicating inadequate ventilation.

- Respiratory Acidosis: Low pH due to elevated PaCO2.

- Metabolic Acidosis: Low pH and low bicarbonate, which can develop due to hypoxemia and increased metabolic demands.

It's important to differentiate RDS from other causes of neonatal respiratory distress, as management differs. These include:

- Transient Tachypnea of the Newborn (TTN): Often seen in term or late-preterm infants, especially after C-section. Characterized by tachypnea, mild distress, and fluid in the fissures on CXR, usually resolving within 24-48 hours.

- Neonatal Pneumonia/Sepsis: Can mimic RDS clinically and radiologically. May require blood cultures and antibiotic treatment.

- Meconium Aspiration Syndrome (MAS): Occurs when infants aspirate meconium-stained amniotic fluid. CXR shows patchy infiltrates, hyperexpansion.

- Persistent Pulmonary Hypertension of the Newborn (PPHN): Can occur secondary to other lung conditions or independently.

- Congenital Heart Disease: Certain cardiac lesions can cause respiratory distress.

- Congenital Lung Anomalies: E.g., diaphragmatic hernia, congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation (CCAM).

The management of RDS is multi-faceted, focusing on preventing the condition, providing adequate respiratory support, replacing deficient surfactant, and managing potential complications. It encompasses both prenatal and postnatal interventions.

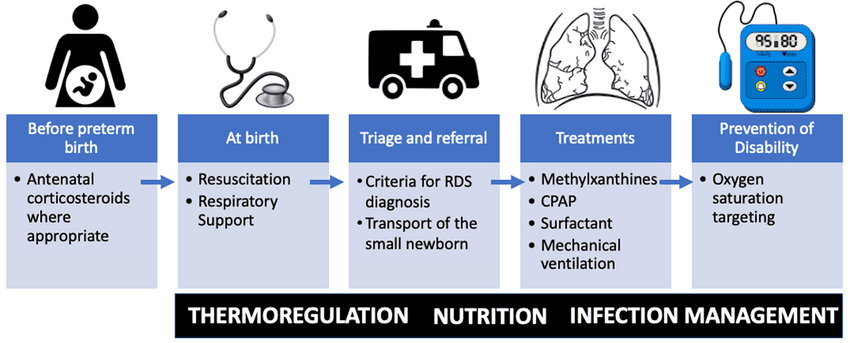

These interventions are aimed at preventing or reducing the severity of RDS before birth.

- Recommendation: Administer to pregnant women at risk of preterm delivery between 24 and 34 weeks of gestation (some guidelines extend this to 36+6 weeks in specific circumstances).

- Example Dose: Dexamethasone (often 6mg IM every 12 hours for 4 doses) or Betamethasone (12mg IM every 24 hours for 2 doses).

- Significantly reduces the incidence and severity of RDS, intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH), and neonatal mortality.

Optimizing the delivery room environment and initial care is crucial for infants at risk of RDS.

- Interventions: Pre-warmed radiant warmer, plastic wraps/bags, thermal mattresses, warm blankets, warm humidified gases.

These are the direct treatment strategies once RDS is diagnosed or highly suspected.

- Indication: Reserved for infants who fail CPAP (e.g., persistent hypoxemia, hypercapnia, increasing work of breathing, recurrent apnea) or require surfactant administration.

- Mechanism: Delivers breaths with specific pressures, volumes, and respiratory rates. Modern ventilation strategies focus on "gentle ventilation" using low tidal volumes, appropriate PEEP, and permissive hypercapnia to minimize lung injury.

- Indication: An advanced mode of ventilation for severe RDS or when conventional ventilation is inadequate, it uses very small tidal volumes at very high frequencies.

- Mechanism: Aims to provide gas exchange while minimizing lung distension and injury.

- Mechanism: Exogenous surfactant preparations are instilled directly into the infant's trachea. They immediately supplement the deficient endogenous surfactant, reducing alveolar surface tension, preventing alveolar collapse, and improving lung compliance and gas exchange.

- Administration: Given via an endotracheal tube. Techniques like LISA (Less Invasive Surfactant Administration) or MIST (Minimally Invasive Surfactant Therapy) using a thin catheter can be employed to deliver surfactant while the infant remains on CPAP, avoiding intubation if possible.

- Timing: Most effective when given early in the course of RDS, ideally within the first few hours of life (prophylactic or early rescue). Repeat doses may be required.

- Examples: (N/S, D5%; (Neonatalyte i.e. D50%= 70mls, D5% = 310 & R/L=120ML). Crystalloid solutions like Normal Saline (N/S) or Ringer's Lactate (R/L) might be used for volume expansion if needed for hypotension.

- Mechanism: Maintain hydration, provide essential glucose to prevent hypoglycemia (which is common in stressed premature infants and can worsen brain injury), and correct electrolyte imbalances.

- Mechanism: Given empirically to rule out or treat early-onset sepsis, which can mimic RDS or coexist with it. A course of antibiotics is typically started until culture results are available and infection is ruled out.

- Example: Ampicillin + Gentamicin or Cefotaxime.

- Mechanism: Infants with RDS have increased metabolic demands and cannot feed orally due to respiratory distress. Enteral feeding (initially trophic feeds via nasogastric tube) is crucial for gut health and eventually growth, once stable. Parenteral nutrition may be needed if enteral feeds are not tolerated.

- Mechanism: Standard prophylactic administration at birth for all newborns to prevent Vitamin K deficiency bleeding. Particularly important in premature infants due to increased risk of intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) if coagulopathy is present.

- Mechanism: May be required for intubated and ventilated infants to reduce agitation, improve ventilator synchrony, and minimize oxygen consumption.

- Reasoning: Essential to assess the infant's response to therapy, detect deterioration, and identify complications.

Providing clear, empathetic, and regular updates to parents is vital for their emotional well-being and helps them cope with the stress of having a premature infant with a serious illness.

Despite significant advances in neonatal care, infants with RDS remain at risk for various complications, both in the short-term (acute) and long-term.

These complications arise during the immediate course of RDS treatment.

- Air Leak Syndromes (Pulmonary Air Leaks): Occur when air escapes from the lungs into surrounding tissues.

- Types:

- Pneumothorax: Air in the pleural space (between lung and chest wall), compressing the lung. Can be spontaneous or due to positive pressure ventilation.

- Pneumomediastinum: Air in the mediastinum (center of the chest).

- Pneumopericardium: Air in the pericardial sac (around the heart), a life-threatening emergency.

- Pulmonary Interstitial Emphysema (PIE): Air trapped within the lung tissue itself, often a precursor to other air leaks.

- Risk Factors: Mechanical ventilation, high ventilator pressures, fragile immature lungs.

- Clinical Signs: Sudden worsening of respiratory distress, asymmetry of chest movement, decreased breath sounds, hypotension.

- Types:

- Intraventricular Hemorrhage (IVH): Bleeding into the brain's ventricular system, where cerebrospinal fluid is produced and circulates.

- Risk Factors: Extreme prematurity (especially <32 weeks), rapid changes in cerebral blood flow (e.g., fluctuations in blood pressure, aggressive fluid administration), birth asphyxia, acidosis, pneumothorax.

- Patent Ductus Arteriosus (PDA): The ductus arteriosus (a fetal blood vessel connecting the aorta and pulmonary artery) fails to close after birth, leading to left-to-right shunting of blood.

- Risk Factors: Prematurity, hypoxemia, fluid overload.

- Consequences: Can lead to increased pulmonary blood flow, pulmonary edema, worsening lung compliance, and heart failure. Can also steal blood flow from other organs.

- Clinical Signs: Bounding pulses, heart murmur, active precordium, increased ventilator support requirements.

- Necrotizing Enterocolitis (NEC): A serious gastrointestinal disease characterized by inflammation and necrosis of the bowel, primarily affecting premature infants.

- Risk Factors: Extreme prematurity, perinatal asphyxia, formula feeding, often associated with systemic illness.

- Consequences: Can lead to bowel perforation, peritonitis, sepsis, and need for surgery.

- Sepsis: Systemic infection.

- Risk Factors: Prematurity, immature immune system, invasive procedures (e.g., intubation, central lines), prolonged hospitalization.

- Consequences: Can worsen respiratory distress, lead to multi-organ failure, and increase mortality.

- Retinopathy of Prematurity (ROP): Abnormal blood vessel growth in the retina, potentially leading to retinal detachment and blindness.

- Risk Factors: Extreme prematurity, high or fluctuating oxygen levels, prolonged oxygen therapy.

- Screening: All premature infants are screened for ROP, especially those born before 30 weeks or weighing <1500g.

- Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia (BPD) / Chronic Lung Disease (CLD): A chronic lung condition affecting premature infants who required prolonged respiratory support. Defined by oxygen requirement at 28 days or 36 weeks postmenstrual age.

- Mechanism: Multifactorial, involves lung injury from mechanical ventilation and oxygen toxicity, inflammation, and arrested lung development.

- Consequences: Persistent respiratory symptoms, increased susceptibility to respiratory infections, prolonged oxygen dependence, rehospitalizations.

- Neurodevelopmental Impairment: A spectrum of challenges including cerebral palsy, developmental delay (motor, cognitive, speech), learning disabilities, and behavioral problems.

- Risk Factors: Extreme prematurity, severe IVH, periventricular leukomalacia (PVL), prolonged hypoxemia/ischemia, severe sepsis.

- Prognosis: More common with decreasing gestational age and increasing severity of acute complications.

- Chronic Respiratory Morbidity: Infants with BPD/CLD may have ongoing respiratory problems such as recurrent wheezing, asthma-like symptoms, increased susceptibility to respiratory infections (especially RSV), and reduced exercise tolerance.

- Prognosis: While many improve over time, some may have lifelong lung function abnormalities.

- Growth Impairment: Preterm infants, especially those with severe RDS and complications, may experience growth faltering.

- Risk Factors: High metabolic demands, feeding difficulties, prolonged hospitalization.

- Hearing Impairment: Extreme prematurity, prolonged exposure to loud NICU environment, certain ototoxic medications. All NICU graduates undergo hearing screening.

The prognosis is generally good for most infants who survive the acute phase, but it varies significantly based on gestational age, severity of RDS, and the presence of complications.

- Survival Rate: Survival rates for infants with RDS are very high, particularly for those born after 28-30 weeks' gestation. Even extremely premature infants (23-24 weeks) have significantly improved survival.

- Gestational Age: The single most important factor influencing prognosis. The more premature the infant, the higher the risk of severe RDS, complications, and long-term sequelae.

- Severity of RDS: Milder forms of RDS are associated with fewer complications and better outcomes.

- Presence of Complications: The development of major complications (e.g., severe IVH, severe BPD) significantly worsens the long-term neurodevelopmental and respiratory prognosis.

- Long-Term Outcome:

- Most infants who survive RDS, particularly those without severe complications, will have normal or near-normal neurodevelopmental outcomes.

- A significant proportion, especially the most premature, will require ongoing medical follow-up for potential developmental, respiratory, or other health issues.

Nursing care for an infant with RDS is complex, requiring vigilant assessment, skilled interventions, and continuous monitoring to optimize respiratory function, minimize complications, and support the infant's overall well-being and development.

- Related To: Alveolar-capillary membrane changes (due to surfactant deficiency), altered oxygen supply (hypoventilation, atelectasis), altered blood flow (PDA), altered oxygen-carrying capacity of blood.

- As Evidenced By: Tachypnea, grunting, nasal flaring, retractions, cyanosis, hypoxemia (low SpO2, low PaO2), hypercapnia (high PaCO2), respiratory acidosis.

| Specific Nursing Interventions | Detail/Rationale |

|---|---|

| 1. Maintain Patent Airway and Optimize Respiratory Function |

|

| 2. Administer and Monitor Respiratory Therapies |

|

| 3. Continuous Monitoring and Assessment |

|

| 4. Promote Energy Conservation |

|

- Related To: Neuromuscular immaturity, decreased lung compliance, metabolic acidosis, fatigue of respiratory muscles.

- As Evidenced By: Tachypnea, apnea, shallow respirations, nasal flaring, retractions, grunting, desaturations.

| Specific Nursing Interventions | Detail/Rationale |

|---|---|

| 1. Monitor and Document Breathing Pattern |

|

| 2. Provide Respiratory Support as Needed |

|

| 3. Manage Medications |

|

| 4. Minimize Environmental Stimuli |

|

- Related To: Immaturity of renal system, insensible water losses (through immature skin, radiant warmer), third spacing of fluid, increased metabolic rate, medication effects.

| Specific Nursing Interventions | Detail/Rationale |

|---|---|

| 1. Accurate Fluid Intake and Output |

|

| 2. Monitor Hydration Status |

|

| 3. Administer IV Fluids and Medications |

|

| 4. Maintain Thermal Neutrality |

|

- Related To: Immature thermoregulation, large surface area to mass ratio, thin skin, decreased subcutaneous fat, impaired metabolic response.

- As Evidenced By: Unstable body temperature, cool/flushed skin, increased oxygen consumption.

| Specific Nursing Interventions | Detail/Rationale |

|---|---|

| 1. Maintain Neutral Thermal Environment |

|

| 2. Monitor Temperature |

|

| 3. Recognize and Address Causes |

|

- Related To: Immature immune system, invasive procedures (ETT, IVs), prolonged hospitalization, broken skin integrity.

- As Evidenced By: Potential signs of sepsis (temperature instability, poor feeding, lethargy, increased respiratory distress, abnormal lab values).

| Specific Nursing Interventions | Detail/Rationale |

|---|---|

| 1. Strict Aseptic Technique |

|

| 2. Hand Hygiene |

|

| 3. Environmental Cleanliness |

|

| 4. Monitor for Signs of Infection |

|

| 5. Administer Antibiotics |

|

- Related To: Environmental overstimulation, pain/discomfort, sleep-wake cycle disruption, prolonged hospitalization.

- As Evidenced By: Irritability, crying, yawning, hiccuping, gaze aversion, poor feeding tolerance, sleep disruption.

| Specific Nursing Interventions | Detail/Rationale |

|---|---|

| 1. Provide Developmentally Supportive Care |

|

| 2. Pain Assessment and Management |

|

- Related To: Situational crisis (preterm birth, infant illness), fear, anxiety, lack of knowledge, separation from infant.

- As Evidenced By: Expressions of fear/anxiety, questions about prognosis, withdrawal from infant, difficulty participating in care.

| Specific Nursing Interventions | Detail/Rationale |

|---|---|

| 1. Provide Emotional Support and Reassurance |

|

| 2. Facilitate Parental Involvement |

|

| 3. Education |

|

| 4. Referrals |

|

| 5. Reassurance |

|

Pingback: Pulmonary Hemorrhage - Nurses Revision

I enjoyed reading the notes…

They are so good,very easy to read and understand…

Thanks so much for making our reading so easy…

Simple notes easy to understand, thanks for the good work,, God bless

Thanks for helping us, we’re really acquiring some knowledge

Thanks for the simplified notes, easy to understand something.

So fablastic notes, could we have more of the nursing interventios in the management of RDS

The note are easily understandable but lengthy

Thank you very much u have helped us a lot

Well summarise

How are surfactants given

I could read this all day without getting tired, thankyou! This is nursing in 5D

thank you, notes are detailed and organized