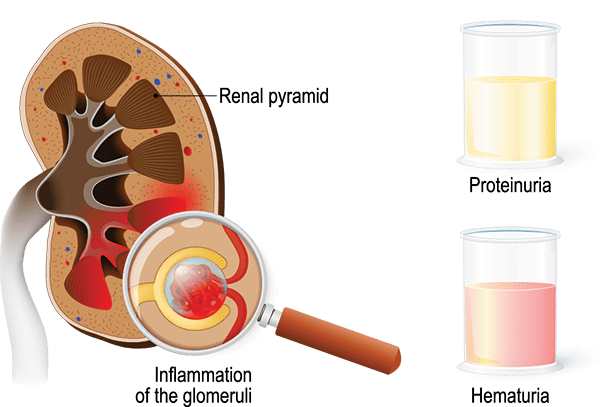

Acute Glomerulonephritis (AGN) is an inflammatory condition affecting the glomeruli of the kidneys. The glomeruli are tiny filtering units within the kidneys responsible for removing waste products and excess fluid from the blood, while retaining important substances like proteins and blood cells.

In AGN, these glomeruli become inflamed, as a result of an immune reaction. This inflammation damages the filtering membranes, leading to:

The term "acute" indicates that the onset is often sudden and the condition develops rapidly, usually over days to weeks. While various forms of glomerulonephritis exist, AGN specifically refers to this sudden onset inflammatory process.

AGN is most frequently triggered by an immune response to an infection elsewhere in the body. The body produces antibodies to fight the infection, but in some cases, these antibodies or immune complexes (antigen-antibody complexes) mistakenly attack or get deposited in the glomeruli, causing inflammation.

- Pharyngitis (Strep Throat): Usually precedes PSGN by about 1-2 weeks (average 10 days).

- Skin Infection (Impetigo or Pyoderma): Can also precede PSGN by about 3-6 weeks (average 3 weeks).

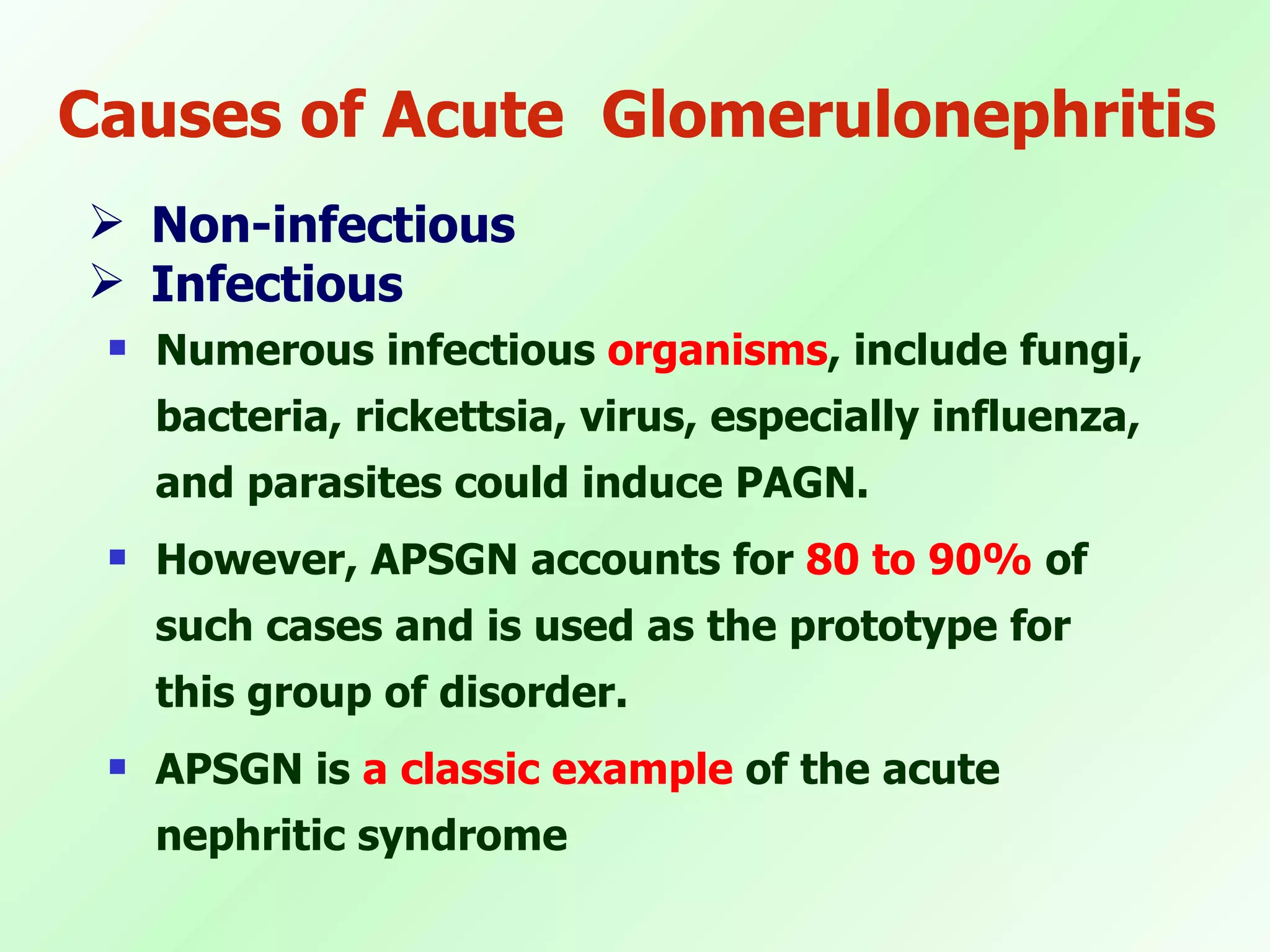

Less common than PSGN, but other bacterial infections can also trigger AGN, including:

Certain viral infections have been implicated, though less frequently:

Malaria and toxoplasmosis can occasionally lead to AGN.

(Less common for "acute" onset but can present as glomerulonephritis): While these usually cause chronic glomerulonephritis, their initial presentation can sometimes mimic AGN:

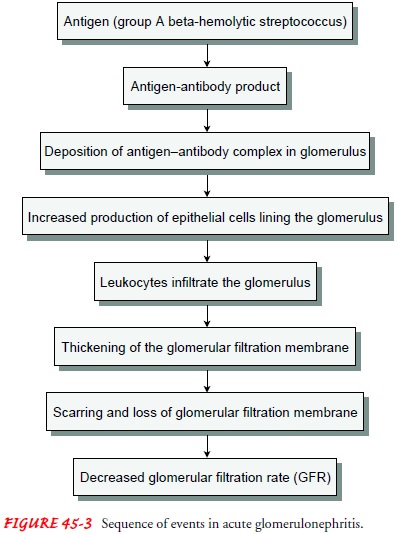

The core of AGN pathophysiology, particularly in the most common form (PSGN), involves a interplay of the immune system and the delicate structure of the glomeruli

- 1-2 weeks after strep pharyngitis.

- 3-6 weeks after strep impetigo.

This is the critical step where the kidney damage occurs. There are two main theories for how these immune complexes or antigens cause glomerular injury:

- Immune complexes formed in the bloodstream circulate and become trapped in the glomerular basement membrane (GBM) or between the endothelial cells and the GBM.

- The size and charge of the complexes, as well as the unique structure of the glomerulus, determine their deposition.

- It's now believed that streptococcal antigens (like SpeB) have a strong affinity for glomerular components (e.g., plasmin).

- These antigens "plant" themselves directly onto the GBM or other glomerular structures.

- Subsequently, circulating antibodies (e.g., anti-SpeB) then bind to these planted antigens in situ within the glomerulus, forming immune complexes directly at the site of injury. This is thought to be a more significant mechanism.

Once the immune complexes are deposited (or formed in situ), they activate the complement system – a cascade of proteins that are part of the innate immune response.

- Recruitment of Inflammatory Cells: Neutrophils, monocytes, and macrophages are attracted to the glomeruli.

- Release of Inflammatory Mediators: These cells release cytokines, chemokines, proteases, and reactive oxygen species.

- Cell Proliferation: Glomerular endothelial and mesangial cells proliferate.

The inflammation and cellular proliferation lead to structural and functional changes in the glomeruli:

- The swelling and cellular proliferation reduce the surface area available for filtration and impede blood flow through the glomeruli.

- This leads to a reduced GFR, causing:

- Oliguria: Decreased urine output.

- Azotemia: Accumulation of nitrogenous waste products (urea, creatinine) in the blood.

- Fluid Retention: Leading to edema (periorbital, peripheral) and hypertension.

- The inflamed and damaged glomerular basement membrane becomes "leaky."

- This allows red blood cells to pass into the urine, causing hematuria (microscopic or macroscopic, resulting in "cola-colored" or "smoky" urine).

- Protein also leaks into the urine, causing proteinuria, though typically not in the nephrotic range (usually <3.5 g/day).

- Following an occurrence of a streptococcal infection which can either be sore throat or a skin infection, there follows an immune response which is mounted against the streptococcal infection (a specific antibody is produced against streptococci)

- These antibodies destroy the glomerulus because it resembles the antigens of the streptococci.

- This usually occurs 2-3 weeks after the streptococcal infection has taken place. This is characterized by diffused inflammation of the renal cortex (glomeruli) of both kidneys.

- The destruction of the glomerulus permits the red blood cells which is passed in urine as haematuria and pus-cells, RBC casts.

- The destruction further causes reduction in the filtration process

- Reduced ultra filtration stimulates angiotensin I release which in turn is changed to angiotensin II which causes constriction of arterioles, hence increasing total arteriolar resistance, leading to elevation of blood pressure.

- Angiotensin ii release further causes production of aldosterone which causes reabsorption of sodium and water, leading to increase in cardiac output and elevation of blood pressure.

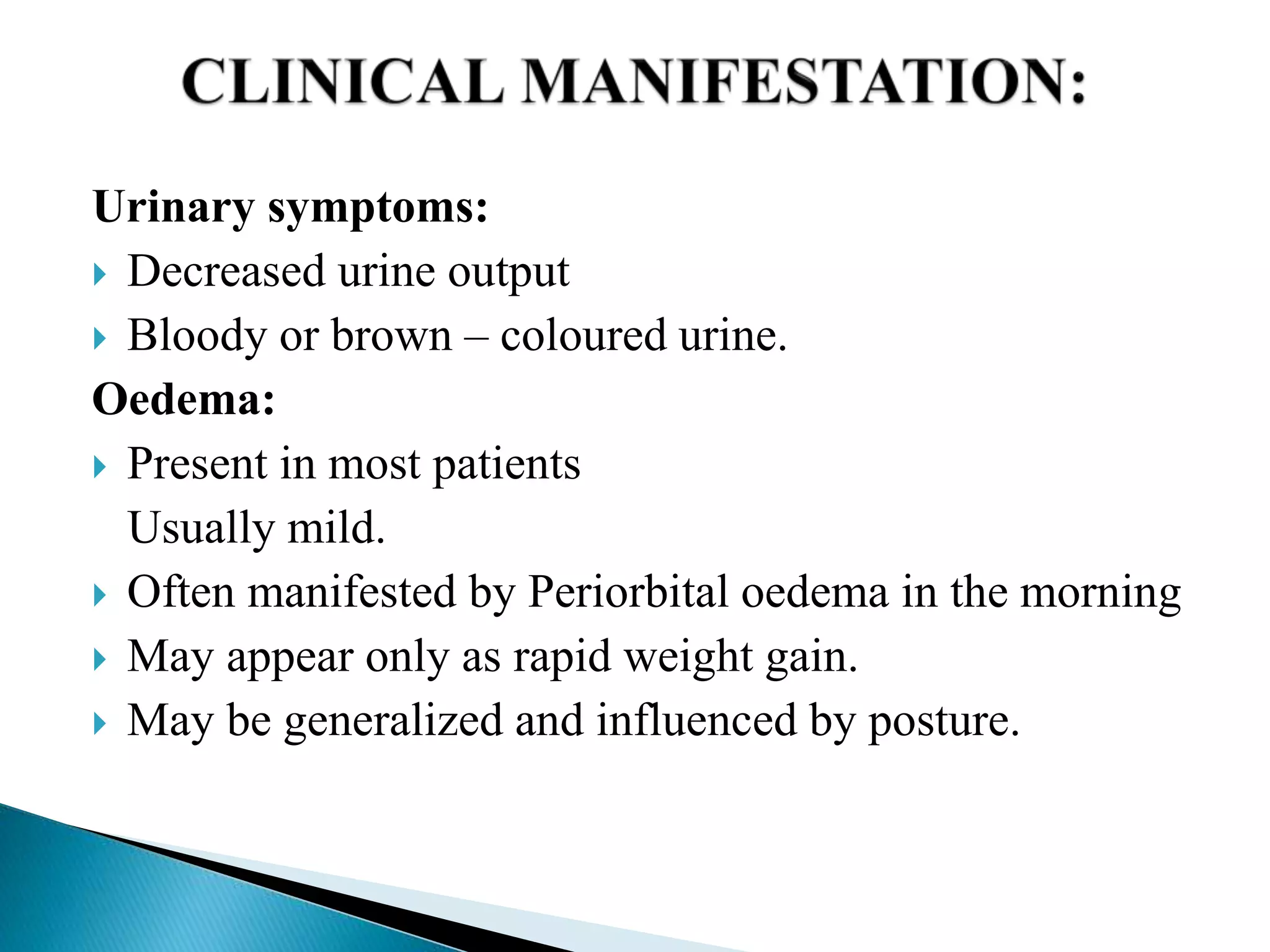

Symptoms typically appear 1-2 weeks after a streptococcal throat infection or 3-6 weeks after a streptococcal skin infection.

- Edema (Swelling):

- Periorbital Edema: Often the first and most noticeable sign, particularly in the morning. Puffiness around the eyes.

- Peripheral Edema: Swelling of the face, hands, and feet (pitting edema may be present).

- Generalized Edema (Anasarca): In severe cases.

- Cause: Fluid retention due to decreased GFR and impaired sodium and water excretion by the damaged kidneys.

- Hypertension (High Blood Pressure):

- Common and Potentially Severe: Occurs in 60-80% of patients.

- Cause: Fluid overload (due to sodium and water retention) and activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system.

- Risk: Can lead to serious complications like hypertensive encephalopathy, seizures, and cardiac failure.

- Hematuria (Blood in Urine):

- Gross Hematuria: Visible "cola-colored," "smoky," "rusty," or reddish-brown urine due to the presence of red blood cells (RBCs) and RBC casts. This is a hallmark sign and occurs in about 30-50% of cases.

- Microscopic Hematuria: Always present, even if urine appears normal. Detected on urinalysis.

- Cause: Increased permeability of the damaged glomerular capillaries, allowing RBCs to leak into the renal tubules.

- Oliguria (Decreased Urine Output):

- Variable: Present in about 50% of patients.

- Severity: Can range from mild reduction to severe oliguria.

- Cause: Markedly reduced GFR.

- Non-Specific Symptoms:

- Fatigue, Lethargy, Malaise: Due to fluid retention and accumulation of waste products.

- Anorexia, Nausea, Vomiting: May occur due to azotemia.

- Abdominal Pain or Flank Pain: Less common, but can occur due to kidney swelling.

- Headache: Often associated with hypertension.

- Shortness of Breath/Dyspnea: If significant fluid overload leads to pulmonary edema or cardiac congestion.

Diagnosis of AGN, especially PSGN, relies on a combination of clinical presentation, laboratory findings, and often evidence of a preceding streptococcal infection.

- C3 (Complement Component 3): Crucial diagnostic marker. Serum C3 levels are typically depressed (low) in 90% of PSGN cases, usually for 6-8 weeks, returning to normal thereafter. This indicates activation and consumption of the complement system.

- C4 levels are usually normal or only slightly reduced, which helps differentiate PSGN from other forms of glomerulonephritis where both C3 and C4 might be low (e.g., lupus nephritis).

- Antistreptolysin O (ASO) Titer: Elevated in 80% of patients following streptococcal pharyngitis. Titer peaks at 3-5 weeks after infection.

- Anti-DNase B Titer (ADB): More sensitive than ASO for skin infections (impetigo) and elevated in both pharyngitis and skin infections.

- Streptozyme Test: Detects multiple streptococcal antibodies.

- Note: Throat cultures may be negative by the time AGN symptoms appear as the infection might have resolved.

When a patient presents with symptoms suggestive of acute glomerulonephritis (edema, hypertension, hematuria, oliguria), clinicians must consider a range of other conditions that can cause similar signs. Differentiating between these conditions is essential, as their etiologies, prognoses, and treatments can vary significantly.

- IgA Nephropathy (Berger's Disease): Often presents with recurrent episodes of gross hematuria, typically occurring concurrently with or within 1-2 days of an upper respiratory tract or gastrointestinal infection (synpharyngitic hematuria).

- Distinguishing Features from PSGN:

- Timing: Hematuria is simultaneous or very soon after infection, not weeks later.

- Complement: Normal C3 levels.

- Pathology: IgA deposits in the mesangium on kidney biopsy (though biopsy usually not done for initial differentiation).

- Distinguishing Features from PSGN:

- Membranoproliferative Glomerulonephritis (MPGN) / C3 Glomerulopathy: Can present with acute nephritic syndrome, often with persistent hypocomplementemia.

- Distinguishing Features from PSGN:

- Complement: C3 levels are persistently low (beyond 8-12 weeks), often accompanied by other complement abnormalities.

- Etiology: Can be primary or secondary to autoimmune diseases, chronic infections (e.g., Hepatitis C), or inherited complement disorders. Often requires kidney biopsy for definitive diagnosis.

- Distinguishing Features from PSGN:

- Lupus Nephritis (Systemic Lupus Erythematosus - SLE): Patients with SLE can develop various forms of glomerulonephritis, including acute nephritic syndrome.

- Distinguishing Features from PSGN:

- Systemic Symptoms: Presence of other systemic manifestations of SLE (arthralgia, rash, serositis, neurological symptoms).

- Serology: Positive ANA, anti-dsDNA antibodies.

- Complement: Both C3 and C4 levels are typically low.

- Distinguishing Features from PSGN:

- ANCA-Associated Glomerulonephritis (e.g., Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis, Microscopic Polyangiitis):

- Presentation: Can cause rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis (RPGN), which includes acute nephritic features. Often presents with severe kidney failure.

- Distinguishing Features from PSGN:

- Systemic Symptoms: May have pulmonary (hemoptysis), sinus, or skin involvement.

- Serology: Positive ANCA (anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies).

- Complement: Normal C3 and C4 levels.

- Anti-Glomerular Basement Membrane (Anti-GBM) Disease (Goodpasture's Syndrome): Rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis, often with pulmonary hemorrhage.

- Distinguishing Features from PSGN:

- Serology: Positive anti-GBM antibodies.

- Complement: Normal C3 and C4 levels.

- Distinguishing Features from PSGN:

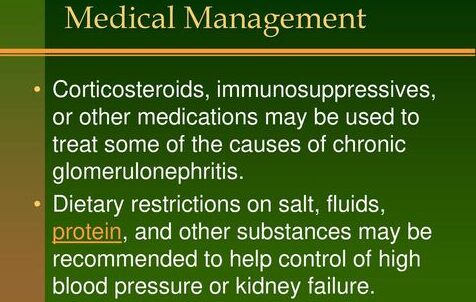

The management of Acute Glomerulonephritis (AGN), particularly PSGN, is primarily supportive, as there is no specific cure for the glomerular inflammation itself. The goals of treatment are to:

- Manage symptoms (edema, hypertension).

- Prevent complications (hypertensive encephalopathy, fluid overload, acute kidney injury).

- Eradicate any residual streptococcal infection (though this does not alter the course of AGN).

- Monitor for recovery.

- Vital Signs: Frequent monitoring of blood pressure (crucial!), heart rate, respiratory rate, and temperature.

- Fluid Balance: Strict intake and output (I&O) measurements are essential. Daily weights are the most sensitive indicator of fluid balance.

- Physical Assessment: Daily assessment for edema, signs of fluid overload (e.g., crackles in lungs, increased work of breathing, jugular venous distension), and neurological status (for hypertensive encephalopathy).

- Laboratory Monitoring:

- Daily or every-other-day BUN, creatinine, and electrolytes (especially potassium, sodium).

- Urinalysis for specific gravity, protein, and hematuria.

- C3 levels (to monitor recovery – should normalize within 6-8 weeks).

- Goal: Prompt and effective control of hypertension is paramount to prevent complications like hypertensive encephalopathy, seizures, and cardiac failure.

- First-line agents:

- Calcium Channel Blockers: (e.g., Nifedipine, Amlodipine) are often preferred for their rapid onset and effectiveness.

- ACE Inhibitors: (e.g., Enalapril) or Angiotensin Receptor Blockers (ARBs) may also be used, but with caution in patients with significant renal impairment or hyperkalemia, as they can further reduce GFR or increase potassium.

- Diuretics:

- Loop Diuretics: (e.g., Furosemide) are effective in reducing fluid overload, which in turn helps lower blood pressure and edema. Often used in conjunction with antihypertensives, especially if signs of volume overload are present.

- Severe Hypertension/Hypertensive Crisis: IV agents like Labetalol or Sodium Nitroprusside may be used in an ICU setting for rapid blood pressure control.

- Furosemide: Widely used to manage fluid overload, edema, and hypertension. It enhances sodium and water excretion.

- Although AGN is an immune-mediated disease and antibiotics do not alter the course of established glomerulonephritis, a 10-day course of Penicillin (or Erythromycin if penicillin allergic) is recommended if there is still evidence of a streptococcal infection (e.g., positive throat culture, recent uncompleted treatment for pharyngitis).

- Eradicate streptococcal causes by oral antibiotic therapy; Penicillin is indicated in nonallergic patients e.g. Phenoxy methyl penicillin 500mg qid. Child: 10 – 20mg per dose Or Amoxicillin 500mg tds. Child: 15mg/kg per dose. If allergic to penicillin give erythromycin every 6hours. Child: 15mg/kg per dose

- This is important to prevent further spread of the nephritogenic strain and to treat any ongoing infection, potentially reducing the risk of recurrence in vulnerable individuals (though recurrence of PSGN is rare).

- Anticonvulsants: If seizures occur secondary to hypertensive encephalopathy, anticonvulsants (e.g., benzodiazepines, phenytoin) may be necessary to control them.

Indications: Dialysis (peritoneal dialysis or hemodialysis) may be required in a small percentage of patients with severe AGN who develop:

- Severe, refractory fluid overload.

- Life-threatening hyperkalemia.

- Severe metabolic acidosis.

- Uremic encephalopathy.

- This is a temporary measure until kidney function recovers.

- Monitoring for Recovery:

- Regular follow-up is essential to ensure complete resolution of AGN and to monitor for any long-term complications.

- Blood Pressure: Should be monitored for at least 6-12 months.

- Urinalysis: Hematuria may persist for several months (up to 1-2 years), and microscopic hematuria can be common. Proteinuria should resolve.

- Renal Function: BUN and creatinine should normalize.

- C3 Levels: Should normalize within 6-8 weeks. Failure to normalize C3 may suggest an alternative diagnosis (e.g., MPGN, lupus nephritis) and might warrant further investigation, including renal biopsy.

- Education: Parents and older children need to understand the importance of ongoing monitoring and to recognize signs of recurrence (though rare for PSGN) or complications.

While the prognosis for typical PSGN is generally excellent, especially in children, the acute phase of AGN can be associated with significant and potentially life-threatening complications. These complications primarily arise from the severely impaired kidney function, fluid overload, and uncontrolled hypertension.

- Hypertensive Encephalopathy: This is a serious and potentially life-threatening complication of severe, uncontrolled hypertension. The rapid rise in blood pressure overwhelms the brain's autoregulatory mechanisms, leading to cerebral edema.

- Clinical Manifestations: Severe Headache, Vomiting, Lethargy, Confusion, Disorientation, Visual Disturbances (e.g., blurred vision, diplopia), Seizures (Focal or Generalized), Coma.

- Intervention: Requires immediate and aggressive control of blood pressure, often with intravenous antihypertensive medications in an intensive care setting.

- Congestive Heart Failure (CHF) / Pulmonary Edema: Severe fluid overload resulting from the kidneys' inability to excrete sodium and water can lead to increased intravascular volume, taxing the heart and causing fluid to accumulate in the lungs.

- Clinical Manifestations: Dyspnea (shortness of breath), Tachypnea (rapid breathing), Orthopnea (difficulty breathing except in an upright position), Cough (often with frothy sputum), Crackles (rales) on lung auscultation, Tachycardia, Gallop rhythm, Peripheral edema, Jugular venous distention.

- Intervention: Diuretics (e.g., IV Furosemide), oxygen therapy, and sometimes positive pressure ventilation.

- Acute Kidney Injury (AKI) / Acute Renal Failure: While reduced GFR is inherent in AGN, severe, prolonged impairment can lead to full-blown AKI.

- Clinical Manifestations: Severe Oliguria or Anuria (absence of urine production), Rapidly rising BUN and Creatinine, Significant Electrolyte Disturbances, Metabolic Acidosis.

- Intervention: Strict fluid and electrolyte management, aggressive diuretic therapy, and if conservative measures fail, dialysis (peritoneal or hemodialysis) may be necessary as a temporary measure until renal function recovers.

- Electrolyte Imbalances:

- Hyperkalemia: A particularly dangerous complication, especially with severe oliguria. The kidneys cannot excrete potassium, leading to dangerously high levels, which can cause life-threatening cardiac arrhythmias.

- Hyponatremia: Can occur due to dilution from excessive fluid retention relative to sodium.

- Hyperphosphatemia and Hypocalcemia: Less common acutely but can develop with more prolonged or severe renal failure.

- Metabolic Acidosis: Due to impaired acid excretion by the kidneys.

- Intervention: Dietary restrictions, fluid management, specific medications (e.g., potassium binders, insulin/glucose for hyperkalemia), and dialysis if severe.

- Secondary Infections: Patients with significant fluid overload, edema, and compromised immunity can be more susceptible to secondary infections (e.g., cellulitis in edematous areas, pneumonia).

- Seizures: Primarily due to hypertensive encephalopathy but can also be exacerbated by severe electrolyte disturbances (e.g., hyponatremia) or uremia.

- Persistent Hypertension: While most children's blood pressure normalizes, a small percentage may develop persistent hypertension that requires ongoing management.

- Persistent Proteinuria/Hematuria: Microscopic hematuria can persist for up to 1-2 years. Persistent nephrotic-range proteinuria or significant persistent hematuria beyond typical resolution times should raise suspicion for other forms of glomerular disease or indicate incomplete recovery.

- Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) / End-Stage Renal Disease (ESRD):

- Extremely rare in children with typical PSGN. The vast majority (over 95%) recover completely.

- However, in adults or in atypical/severe cases, or if the underlying glomerulonephritis is not PSGN (e.g., MPGN, rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis), there is a risk of progression to CKD or ESRD.

- Persistent low C3 levels beyond 8-12 weeks are a red flag for a different underlying diagnosis or a less favorable prognosis.

- Excellent Short-Term Prognosis:

- Complete Recovery: The vast majority of children (95-98%) with typical PSGN experience a complete and sustained recovery of renal function.

- Resolution of Symptoms: Clinical symptoms such as edema, hypertension, and gross hematuria typically resolve within a few days to weeks.

- Laboratory Normalization:

- C3 levels usually normalize within 6-8 weeks. Failure to normalize within this timeframe should prompt re-evaluation and consideration of alternative diagnoses or persistent glomerular disease.

- BUN and creatinine normalize as GFR improves.

- Proteinuria resolves within 6 months.

- Microscopic hematuria can be the most persistent finding, sometimes lasting up to 1-2 years, but typically without long-term consequence if other parameters are normal.

- Low Risk of Long-Term Complications:

- Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) / End-Stage Renal Disease (ESRD): Progression to CKD or ESRD is extremely rare (less than 1-2%) in children with classic PSGN.

- Recurrence: Recurrence of PSGN is also very rare, as the initial infection typically confers type-specific immunity.

The prognosis for PSGN in adults is generally considered less favorable than in children.

- Higher Risk of Chronic Kidney Disease: Adults have a higher incidence of persistent renal abnormalities (e.g., persistent proteinuria, hypertension) and a greater risk (up to 10-20%) of progressing to chronic kidney disease. The reasons for this difference are not fully understood but may relate to pre-existing renal damage, co-morbidities, or a less robust recovery capacity.

When AGN is caused by conditions other than PSGN, the prognosis varies widely and can be more guarded.

- Rapidly Progressive Glomerulonephritis (RPGN): Conditions like Anti-GBM disease, severe ANCA-associated vasculitis, or severe lupus nephritis can present as RPGN.

- Prognosis: Without prompt and aggressive immunosuppressive therapy (and sometimes plasma exchange), these conditions can rapidly lead to ESRD within weeks to months. The long-term outcome depends on the severity, response to treatment, and early diagnosis.

- IgA Nephropathy: While it can cause acute nephritic episodes, it is typically a chronic, slowly progressive disease.

- Prognosis: Approximately 20-40% of patients with IgA nephropathy will progress to ESRD over 10-20 years. Factors like persistent hypertension, severe proteinuria, and specific pathological findings influence prognosis.

- Membranoproliferative Glomerulonephritis (MPGN) / C3 Glomerulopathy: These are often chronic conditions that can lead to significant renal impairment and progression to ESRD in a substantial proportion of patients, especially if associated with persistent hypocomplementemia.

Several factors can influence the long-term outcome of AGN:

- Age: Children generally have a better prognosis than adults for PSGN.

- Etiology: PSGN has a better prognosis than many other forms of acute glomerulonephritis.

- Severity of Initial Presentation:

- Severe oliguria, anuria, or the need for dialysis during the acute phase can indicate more extensive renal damage and may be associated with a slightly higher risk of long-term sequelae.

- The presence of crescentic changes on kidney biopsy (indicating severe glomerular injury) is a poor prognostic indicator.

- Persistent Abnormalities:

- Persistent hypertension: A significant risk factor for progressive renal damage.

- Persistent proteinuria: Especially in the nephrotic range, indicates ongoing glomerular damage.

- Failure of C3 levels to normalize: Suggests alternative or chronic glomerular disease.

- Comorbidities: Underlying chronic diseases can worsen the prognosis.

- Related to: Compromised regulatory mechanisms (renal impairment leading to decreased glomerular filtration rate), sodium and water retention.

- As evidenced by: Edema (periorbital, peripheral, sacral), elevated blood pressure, dyspnea, orthopnea, weight gain, oliguria, jugular venous distention, crackles on lung auscultation.

| Intervention | Detail/Rationale |

|---|---|

| Assess and Monitor Fluid Balance |

|

| Fluid Restriction |

|

| Sodium Restriction |

|

| Administer Diuretics |

|

| Positioning |

|

| Skin Care |

|

- Related to: Severe, uncontrolled hypertension, cerebral edema.

- As evidenced by: (Potential for) severe headache, visual disturbances, altered mental status, seizures.

| Intervention | Detail/Rationale |

|---|---|

| Blood Pressure Monitoring |

|

| Administer Antihypertensives |

|

| Neurological Assessment |

|

| Seizure Precautions |

|

| Quiet Environment |

|

- Related to: Anorexia, nausea, vomiting, dietary restrictions (sodium, potassium, protein if severe AKI).

- As evidenced by: Weight loss (though masked by edema), verbalization of poor appetite, aversion to food.

| Intervention | Detail/Rationale |

|---|---|

| Assess Dietary Intake | Monitor food preferences and intake. Note any nausea or vomiting. |

| Dietary Restrictions | Collaborate with a dietitian to plan meals that adhere to prescribed restrictions (low sodium, possibly low potassium, low protein if severe azotemia). Educate patient/family on dietary modifications. |

| Small, Frequent Meals | Offer small, frequent, appealing meals to improve intake. Provide food when the patient is least nauseated. |

| Oral Hygiene | Provide good oral hygiene before meals to enhance appetite. |

| Monitor Lab Values | Monitor BUN, creatinine, albumin, and electrolyte levels. |

- Related to: Compromised immune response (due to underlying disease process), tissue edema, potential for invasive procedures.

- As evidenced by: (Potential for) fever, localized pain, redness, swelling, abnormal white blood cell count.

| Intervention | Detail/Rationale |

|---|---|

| Monitor for Signs of Infection | Regularly assess temperature, observe for chills, localized pain, redness, or swelling. Monitor white blood cell count. |

| Antibiotic Administration | Administer prescribed antibiotics (if there is evidence of ongoing streptococcal infection) as ordered. Educate on the importance of completing the full course. |

| Strict Asepsis | Maintain strict aseptic technique for all invasive procedures (IV insertion, catheter care). |

| Hand Hygiene | Promote frequent and meticulous hand hygiene for patients, staff, and visitors. |

| Skin Integrity | Maintain skin integrity, especially in edematous areas, to prevent breakdown and entry points for bacteria. |

- Related to: Generalized weakness, fatigue, effects of disease process (edema, hypertension).

- As evidenced by: Verbal reports of fatigue, weakness, dyspnea on exertion, increased heart rate/blood pressure with activity.

| Intervention | Detail/Rationale |

|---|---|

| Assess Activity Level | Monitor patient's tolerance to activity. |

| Promote Rest | Encourage bed rest during the acute phase, gradually increasing activity as tolerated and symptoms improve. Provide periods of uninterrupted rest. |

| Assist with ADLs | Assist with activities of daily living (ADLs) as needed to conserve energy. |

| Gradual Mobilization | Gradually increase activity as vital signs stabilize and symptoms resolve. |

- Related to: Unfamiliarity with the disease process, treatment regimen, dietary restrictions, and potential complications.

- As evidenced by: Questions about the disease, incorrect understanding of instructions, non-adherence to regimen.

| Intervention | Detail/Rationale |

|---|---|

| Educate on AGN | Explain AGN in simple terms, including its cause (e.g., strep infection), why it happened, and what to expect during recovery. Emphasize that for PSGN, full recovery is expected. |

| Treatment Plan Education | Explain all medications (purpose, dose, side effects). Reinforce dietary and fluid restrictions. Discuss the importance of daily weights and I&O if monitoring at home. |

| Signs of Complications | Teach signs and symptoms of worsening condition or complications (e.g., severe headache, visual changes, decreased urine output, increased edema, difficulty breathing) and when to seek medical attention. |

| Long-Term Follow-up | Explain the importance of regular follow-up appointments and laboratory tests (blood pressure checks, urinalysis, blood tests) to monitor recovery and detect any potential long-term issues. |

| Written Materials | Provide written educational materials to reinforce verbal teaching. |

Thanks this was well put

thank you for a summarized notes