General signs and symptoms of the nervous system disorders

General Signs and Symptoms of Nervous System Disorders

Introduction

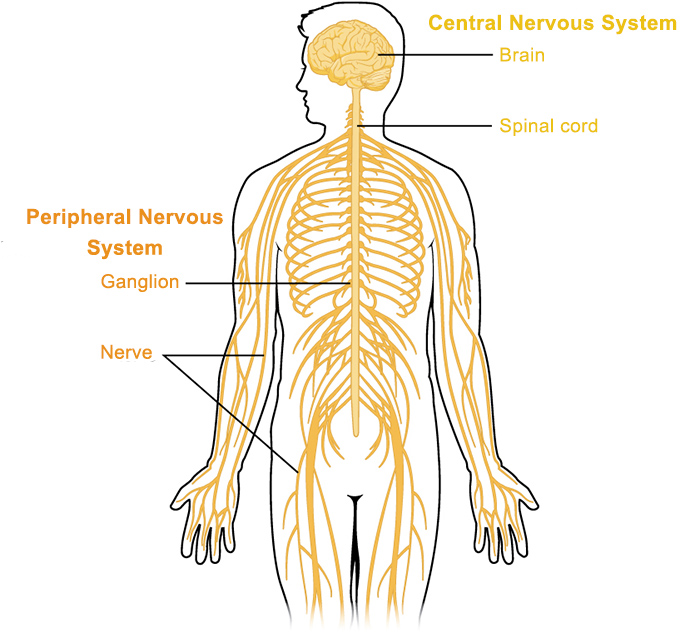

The nervous system, a marvel of biological engineering, orchestrates every thought, movement, sensation, and involuntary bodily function. Its complexity means that disruption at any point—from the brain and spinal cord (central nervous system, CNS) to the peripheral nerves and muscles (peripheral nervous system, PNS)—can lead to a vast array of clinical manifestations. These manifestations are broadly classified as signs (objective findings observed by an examiner) and symptoms (subjective experiences reported by the patient). A deep understanding of these general signs and symptoms is foundational for anyone embarking on the study of neurology, enabling them to interpret patient complaints, perform focused examinations, and begin the critical process of localization (determining where in the nervous system the problem lies) and characterization (understanding the nature of the disease).

Learning Objective 1: Define and differentiate between various categories of neurological signs and symptoms.

Neurological signs and symptoms are incredibly diverse, reflecting the multifaceted roles of the nervous system. To bring order to this diversity, we categorize them based on the primary function or system affected. This systematic classification is not just for academic understanding; it's a practical tool that guides history taking and physical examination, ensuring that no crucial domain of neurological function is overlooked.

1. Motor Symptoms and Signs

These relate to the ability to control movement, encompassing both voluntary actions and involuntary reflexes.

Symptoms (Patient's Experience):

- Weakness (Paresis): A subjective feeling of reduced muscle strength. Patients might describe difficulty lifting objects, climbing stairs, or holding things. If complete loss of strength, it's called paralysis (plegia).

- Clumsiness/Incoordination: Difficulty performing smooth, accurate movements. This could manifest as dropping objects, tripping, or handwriting changes.

- Tremors: Involuntary, rhythmic, oscillatory movements of a body part. Patients might notice their hands shaking, especially when trying to hold a posture or at rest.

- Stiffness/Spasticity: A subjective feeling of resistance to movement.

- Difficulty Walking (Gait Disturbance): Patients may describe shuffling, stumbling, or feeling unsteady.

Signs (Examiner's Observation/Testing):

- Weakness (Paresis/Plegia): Objectively measured using a muscle strength scale (e.g., Medical Research Council, MRC scale 0-5).

- 0: No contraction

- 1: Flicker or trace of contraction

- 2: Active movement, gravity eliminated

- 3: Active movement against gravity

- 4: Active movement against gravity and some resistance

- 5: Normal strength

- Abnormal Movements: Observable involuntary movements like tremors, dystonia (sustained muscle contractions causing twisting), chorea (jerky, dance-like movements), myoclonus (sudden muscle jerks), tics.

- Changes in Muscle Tone: Assessed by passively moving a limb through its range of motion. Can be hypotonia (decreased tone), spasticity (velocity-dependent resistance, "clasp-knife"), or rigidity (constant resistance, "lead-pipe" or "cogwheel").

- Abnormal Reflexes: Testing deep tendon reflexes (DTRs) can reveal hyperreflexia (exaggerated) or hyporeflexia/areflexia (diminished/absent). Presence of pathological reflexes like Babinski sign (extensor plantar response).

- Gait Abnormalities: Observed patterns of walking (e.g., ataxic, parkinsonian, spastic, steppage).

- Muscle Atrophy/Hypertrophy: Observable wasting or enlargement of muscles.

- Fasciculations: Visible, brief, spontaneous contractions of a small number of muscle fibers.

2. Sensory Symptoms and Signs

These involve the perception of stimuli from the body and external environment, including touch, temperature, pain, vibration, and position.

Symptoms (Patient's Experience):

- Numbness (Hypesthesia/Anesthesia): A subjective loss or decrease in sensation. Often described as "dead" or "wooden."

- Tingling/Pins and Needles (Paresthesias): Abnormal, non-painful sensations like prickling, crawling, or buzzing.

- Pain: Can be sharp, burning, shooting, aching, or radiating. Neuropathic pain (nerve pain) has distinct qualities.

- Dysesthesias: Unpleasant, abnormal sensations, often provoked by a non-noxious stimulus (e.g., light touch feels painful).

- Loss of Proprioception: Feeling unsteady or unsure of limb position without looking.

- Visual Disturbances: Blurred vision, double vision (diplopia), loss of peripheral vision, flashing lights.

- Auditory/Vestibular Disturbances: Ringing in ears (tinnitus), hearing loss, spinning sensation (vertigo).

Signs (Examiner's Observation/Testing):

- Decreased or Absent Sensation: Objectively testing sensation to light touch, pinprick (pain), temperature, vibration, and joint position sense.

- Sensory Level: A distinct horizontal line on the body below which sensation is abnormal, highly suggestive of a spinal cord lesion.

- Visual Field Defects: Detected through confrontation visual field testing.

- Pupillary Abnormalities: Unequal pupils (anisocoria), abnormal reaction to light, ptosis (drooping eyelid) can be part of sensory nerve dysfunction.

- Nystagmus: Rhythmic, involuntary eye movements.

- Romberg Sign: Inability to maintain balance with eyes closed (suggests proprioceptive loss or vestibular dysfunction).

3. Cognitive and Higher Cortical Function Symptoms and Signs

These relate to thought processes, memory, language, and executive functions.

Symptoms (Patient/Family Report):

- Memory Loss: For recent events, names, dates.

- Difficulty Concentrating/Attention Deficits: Easily distracted, trouble focusing on tasks.

- Language Problems: Difficulty finding words (anomia), understanding spoken or written language, speaking fluently.

- Confusion/Disorientation: Not knowing where they are, what time it is, or who people are.

- Problem-Solving Difficulties: Trouble making decisions, planning, or managing finances.

- Personality/Behavioral Changes: Increased irritability, apathy, disinhibition.

Signs (Examiner's Observation/Testing):

- Impaired Performance on Cognitive Screens: (e.g., Mini-Mental State Examination, MMSE; Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA).

- Aphasia: Objectively demonstrated language deficits (e.g., poor fluency, impaired comprehension, paraphasias).

- Disorientation: To person, place, or time.

- Executive Dysfunction: Observed difficulty with tasks requiring planning, sequencing, or abstract thought.

- Agnosia: Inability to recognize familiar objects despite intact sensory input.

- Apraxia: Inability to perform learned motor acts despite intact motor function and comprehension.

4. Autonomic Symptoms and Signs

These arise from dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system, which controls involuntary bodily functions like heart rate, blood pressure, digestion, and sweating.

Symptoms (Patient's Experience):

- Dizziness/Lightheadedness upon Standing: Suggestive of orthostatic hypotension.

- Bladder Dysfunction: Urinary urgency, frequency, incontinence, difficulty initiating urination, or incomplete bladder emptying.

- Bowel Dysfunction: Constipation, fecal incontinence.

- Sexual Dysfunction: Erectile dysfunction, decreased libido.

- Abnormal Sweating: Excessive (hyperhidrosis) or absent (anhidrosis) sweating.

- Difficulty with Temperature Regulation.

Signs (Examiner's Observation/Testing):

- Orthostatic Hypotension: Measured drop in blood pressure when changing from supine to standing position.

- Abnormal Pupillary Responses: Sluggish reaction to light, anisocoria (unequal pupils).

- Skin Changes: Dry, fissured skin (anhidrosis), or excessively moist skin.

5. Psychiatric Symptoms and Signs

Neurological disorders frequently present with or exacerbate psychiatric manifestations, sometimes even as the initial presenting complaint.

Symptoms (Patient/Family Report):

- Depression/Anxiety: Persistent sadness, loss of interest, excessive worry, panic attacks.

- Irritability/Mood Swings: Uncharacteristic changes in temperament.

- Hallucinations/Delusions: Seeing, hearing, or believing things that aren't real.

- Apathy: Lack of motivation or emotional response.

- Disinhibition: Acting without regard for social norms or consequences.

Signs (Examiner's Observation/Assessment):

- Observed Mood/Affect: Flat, blunted, labile, or incongruent affect.

- Psychomotor Agitation or Retardation: Restlessness or slowed movements.

- Disorganized Thought/Speech: Rambling, illogical speech patterns.

- Delusional Ideation: Fixed, false beliefs.

6. Other General Neurological Symptoms and Signs

- Headaches: A very common neurological symptom, ranging from benign tension headaches to severe migraines or indicators of serious intracranial pathology.

- Seizures: Episodes of abnormal electrical activity in the brain, leading to changes in movement, sensation, behavior, or consciousness. Can be focal (starting in one area) or generalized (affecting both hemispheres).

- Fatigue: Profound, debilitating tiredness not relieved by rest, common in conditions like multiple sclerosis.

- Sleep Disturbances: Insomnia, hypersomnia, parasomnias (e.g., REM sleep behavior disorder).

Learning Objective 2: Explain the significance of a thorough neurological history and physical examination in identifying neurological dysfunction.

The neurological history and physical examination are the cornerstones of neurological diagnosis. They are Sherlock Holmes's magnifying glass and notebook, providing indispensable clues that, when meticulously collected and logically interpreted, allow the clinician to pinpoint the problem within the vast complexity of the nervous system.

1. The Neurological History: The Patient's Story

The history is paramount because many neurological symptoms are subjective. It focuses on the patient's narrative, systematically gathering information about their experiences.

- Onset: How did the symptoms begin?

- Acute (minutes to hours): Often suggests vascular events (stroke), traumatic injury, seizures, or acute demyelination. Example: Sudden weakness on one side of the body.

- Subacute (days to weeks): Common with inflammatory processes (e.g., Guillain-Barré syndrome), infections (e.g., encephalitis), or rapidly growing tumors. Example: Weakness gradually worsening over a week.

- Chronic (months to years): Typical for degenerative diseases (e.g., Parkinson's, Alzheimer's), slowly progressive tumors, or chronic demyelinating conditions. Example: Hand tremors gradually worsening over several years.

- Episodic/Fluctuating: Symptoms that come and go, or vary in intensity. Suggests conditions like migraine, epilepsy, multiple sclerosis (relapsing-remitting form), or myasthenia gravis. Example: Episodes of blindness that resolve completely.

- Progression: How have the symptoms changed since onset? Improving, worsening, stable, or fluctuating? This helps characterize the disease course.

- Character of Symptoms: Detailed description of the symptoms (e.g., type of pain, quality of weakness, nature of visual changes).

- Location and Radiation: Where are the symptoms felt, and do they spread? (e.g., pain radiating down the leg).

- Severity: How much do the symptoms interfere with daily life? (e.g., using a scale of 1-10 for pain).

- Timing: When do the symptoms occur? (e.g., worse in the morning, only with activity).

- Associated Symptoms: Any other symptoms that occur alongside the primary complaint. This is vital for connecting different system involvements (e.g., headache with fever and stiff neck points to meningitis; weakness with sensory loss in the same distribution).

- Exacerbating and Relieving Factors: What makes the symptoms better or worse? (e.g., rest, specific positions, medications).

- Occupation: Exposure to toxins, repetitive strain injuries.

- Lifestyle: Smoking, alcohol, recreational drug use.

- Travel History: Exposure to endemic infectious diseases.

- Support System: Important for management and rehabilitation.

The significance of the history lies in its ability to generate hypotheses about the localization and etiology (cause) of the neurological problem even before the physical exam begins. A well-taken history is often more diagnostic than any single test.

2. The Neurological Physical Examination: Objective Evidence

The physical examination systematically assesses neurological function, aiming to objectively confirm symptoms, elicit signs the patient may not be aware of, and localize the lesion.

- Mental Status Examination (Cognition)

- Cranial Nerve Examination

- Motor System Examination

- Sensory System Examination

- Coordination and Gait Examination

Example: Weakness, hyperreflexia, and spasticity in one arm and leg would point to an Upper Motor Neuron lesion in the contralateral cerebral hemisphere or ipsilateral spinal cord.

Learning Objective 3: Describe common motor symptoms associated with nervous system disorders.

Motor symptoms and signs are fundamental indicators of nervous system dysfunction, as they directly reflect issues within the pathways and structures responsible for planning, initiating, and executing movement. These can range from subtle changes in coordination to profound paralysis, providing critical clues to the location and nature of the underlying neurological pathology.

1. Weakness (Paresis) and Paralysis (Plegia)

The most common motor symptom, describing a reduction or complete loss of muscle strength. Understanding its pattern is key.

Definitions:

- Paresis: Partial or incomplete loss of muscle strength. The patient can still move the affected limb or muscle, but with reduced power.

- Paralysis (Plegia): Complete loss of muscle strength, rendering the patient unable to move the affected part at all.

Patterns of Weakness (Crucial for Localization):

- Hemiparesis/Hemiplegia: Weakness/paralysis affecting one side of the body (e.g., right arm and right leg). This typically indicates a lesion in the contralateral cerebral hemisphere (e.g., stroke affecting the left motor cortex results in right-sided weakness) or in the ipsilateral brainstem (if the lesion is below the decussation of corticospinal tracts).

- Paraparesis/Paraplegia: Weakness/paralysis affecting both lower limbs. This is highly suggestive of a lesion in the spinal cord (thoracic, lumbar, or sacral levels) or conditions affecting bilateral peripheral nerves to the legs.

- Quadriparesis/Quadriplegia (Tetraparesis/Tetraplegia): Weakness/paralysis affecting all four limbs. This points to a severe lesion in the cervical spinal cord, brainstem, or generalized neuromuscular junction/muscle disorders affecting all limbs.

- Monoparesis/Monoplegia: Weakness/paralysis affecting a single limb (e.g., one arm or one leg). This could be due to a focal lesion in the motor cortex, a peripheral nerve lesion affecting that limb, or a radiculopathy.

Distal vs. Proximal Weakness:

- Distal Weakness: Predominantly affects muscles furthest from the body's midline (e.g., hands and feet, such as foot drop). Often seen in peripheral neuropathies ("stocking-glove" distribution) or some motor neuron diseases.

- Proximal Weakness: Predominantly affects muscles closest to the body's midline (e.g., shoulders and hips, leading to difficulty raising arms above the head or climbing stairs). Typical of myopathies (muscle diseases) and disorders of the neuromuscular junction (e.g., myasthenia gravis).

Fatigability: Weakness that worsens significantly with sustained or repetitive activity and improves with rest. This is a hallmark of neuromuscular junction disorders, most famously myasthenia gravis.

2. Abnormal Movements (Involuntary Movements / Dyskinesias)

These are movements that occur outside of voluntary control. Their characteristics help narrow down the neuroanatomical location, often implicating the basal ganglia or cerebellum.

- Resting Tremor: Present when the limb is at rest, diminishes or disappears with voluntary movement. The classic "pill-rolling" tremor of Parkinson's disease is an example, often asymmetrical and worse at rest. Implicates basal ganglia pathology.

- Action/Intention Tremor: Absent at rest, appears or worsens with voluntary movement, becoming most pronounced as the limb approaches a target. Characteristic of cerebellar dysfunction (e.g., multiple sclerosis, stroke affecting the cerebellum).

- Postural Tremor: Present when a limb is actively held against gravity (e.g., holding arms outstretched). The most common type is Essential Tremor, which can affect hands, head, or voice.

3. Changes in Muscle Tone

Muscle tone refers to the resistance of a muscle to passive stretch. Abnormalities indicate lesions in motor pathways.

- Spasticity: Velocity-dependent increase in tone, meaning resistance increases with faster passive movement. Characterized by the "clasp-knife" phenomenon (initial strong resistance followed by a sudden release). It is a classic sign of upper motor neuron (UMN) lesions (e.g., stroke, multiple sclerosis, spinal cord injury). Affects antigravity muscles (flexors in arms, extensors in legs).

- Rigidity: Non-velocity-dependent increase in tone, meaning resistance is constant throughout the range of motion, regardless of speed.

- Lead-pipe Rigidity: Sustained, uniform resistance throughout the entire range of movement.

- Cogwheel Rigidity: Lead-pipe rigidity with superimposed tremor, creating a jerky, ratchet-like quality when moving the limb. Both types are characteristic of Parkinson's disease and other conditions affecting the basal ganglia.

4. Gait Disturbances and Imbalance (Ataxia)

Abnormalities in walking and maintaining balance are significant indicators of neurological dysfunction.

- Cerebellar Ataxia: Characterized by a broad-based, unsteady, staggering, "drunken" gait. Patients often have difficulty with tandem walking (heel-to-toe). Associated with other cerebellar signs like intention tremor, dysmetria (inaccurate movements), and dysdiadochokinesia (impaired rapid alternating movements). Lesions in the cerebellum or its connections.

- Sensory Ataxia: Due to loss of proprioception (sense of body position), usually from damage to the dorsal columns of the spinal cord or large fiber peripheral neuropathies. Patients compensate by watching their feet and walking with a wide base. This gait significantly worsens with eye closure (positive Romberg sign).

- Hemiparetic: One leg is stiff and extended, dragging in a semicircle (circumduction) due to spasticity of hip adductors and extensors and knee extensors (classic in hemiplegia post-stroke).

- Scissoring: Both legs are stiff, adducted, and cross in front of each other, seen in bilateral spasticity (e.g., cerebral palsy).

5. Dysphagia (Swallowing Difficulties)

Problems with swallowing can lead to aspiration (food/liquid entering the airway) and malnutrition.

6. Dysarthria (Speech Articulation Difficulties)

Difficulty articulating words due to weakness, paralysis, or incoordination of the muscles involved in speech production (lips, tongue, palate, larynx, diaphragm).

- Spastic Dysarthria (UMN): Harsh, strained-strangled voice, slow speech, imprecise articulation. Associated with bilateral upper motor neuron lesions (e.g., pseudobulbar palsy post-stroke, ALS).

- Flaccid Dysarthria (LMN): Breathy, weak, often hypernasal voice, imprecise consonants. Associated with lower motor neuron lesions affecting cranial nerves (e.g., bulbar palsy, myasthenia gravis, GBS).

- Ataxic Dysarthria (Cerebellar): "Scanning" speech, irregular rate and rhythm, imprecise articulation, explosive bursts of loudness. Associated with cerebellar dysfunction.

- Hypokinetic Dysarthria (Parkinsonian): Monopitch, monoloudness, reduced stress, rapid or "festinating" speech, indistinct articulation. Characteristic of Parkinson's disease.

- Hyperkinetic Dysarthria (Chorea/Dystonia): Irregular, harsh, strained voice, sudden changes in pitch and loudness, involuntary grunts or shouts. Associated with basal ganglia disorders (e.g., Huntington's).

7. Muscle Atrophy and Fasciculations

- Neurogenic Atrophy: Rapid and often severe, due to denervation from LMN lesions (e.g., peripheral nerve injury, motor neuron disease).

- Disuse Atrophy: Slower and less severe, due to prolonged inactivity or immobilization.

Learning Objective 4: Identify key sensory symptoms indicative of nervous system involvement.

Sensory symptoms arise from dysfunction anywhere along the pathways that transmit information about touch, pain, temperature, vibration, and proprioception from the body to the brain, or within the brain itself. These pathways are distinct for different sensory modalities, meaning that specific patterns of sensory loss can be highly localizing. Sensory complaints are among the most common reasons patients seek neurological evaluation.

1. Numbness (Hypesthesia / Anesthesia)

This is the most common sensory complaint, indicating a reduction or complete loss of sensation.

- Hypesthesia: Decreased sensation. Patients might describe a feeling of "deadness," "woodenness," or being "gloved" in the affected area. They may say they can feel touch, but it's diminished or dull.

- Anesthesia: Complete loss of sensation. The patient feels nothing in the affected region.

Patterns of Numbness (Crucial for Localization):

- Dermatomal Pattern: Numbness in a specific area supplied by a single nerve root (e.g., C6 dermatome in the thumb and radial forearm). Suggests radiculopathy (nerve root compression, such as from a herniated disc).

- Peripheral Nerve Distribution: Numbness confined to the distribution of a specific peripheral nerve (e.g., median nerve distribution in carpal tunnel syndrome). Suggests peripheral neuropathy or mononeuropathy.

- "Stocking-Glove" Distribution: Numbness affecting the feet and then gradually extending upwards, followed later by numbness in the hands, in a symmetrical pattern. This is characteristic of polyneuropathies (e.g., diabetic neuropathy, B12 deficiency), where the longest nerves are affected first.

- Hemisensory Loss: Numbness on one entire side of the body. Points to a lesion in the contralateral thalamus or parietal cortex.

- Sensory Level: A distinct horizontal line on the torso or limbs below which sensation is altered or lost. This is a classic sign of a spinal cord lesion, indicating the upper level of damage.

2. Tingling and Paresthesias

These are abnormal, non-painful sensations.

- Paresthesias: Spontaneous, usually non-painful, abnormal sensations such as "pins and needles," prickling, buzzing, crawling, or tingling, occurring without an obvious stimulus. They often accompany or precede numbness and are a sign of irritation or damage to sensory nerves.

- Dysesthesias: Unpleasant, abnormal sensations, often provoked by a stimulus that would not normally be noxious. For example, light touch might feel painful, burning, or intensely itchy.

3. Pain (Neuropathic Pain, Radicular Pain, Thalamic Pain)

Pain is a complex sensation, and when it arises from neurological dysfunction, it has specific characteristics.

- Characteristics: Often described as burning, shooting, stabbing, electrical, lancinating, gnawing, or aching. Can be accompanied by allodynia (pain from a non-painful stimulus) or hyperalgesia (exaggerated pain from a mildly painful stimulus).

- Causes: Diabetic neuropathy, post-herpetic neuralgia, trigeminal neuralgia, spinal cord injury, stroke.

- Characteristics: Sharp, shooting pain, often accompanied by numbness or weakness in the same distribution.

- Examples: Sciatica (pain radiating down the leg from lumbar nerve root compression), brachialgia (pain radiating down the arm from cervical nerve root compression).

- Primary Headaches: Headaches that are not symptoms of another disorder (e.g., migraine, tension headache, cluster headache).

- Secondary Headaches: Headaches caused by an underlying condition, which can be life-threatening.

- Red Flags: "Worst headache of my life" (consider subarachnoid hemorrhage), sudden onset, associated fever/stiff neck (meningitis), focal neurological deficits, papilledema (raised intracranial pressure), headache in an elderly patient with jaw claudication (giant cell arteritis).

4. Loss of Specific Sensations

Damage to particular sensory pathways can selectively impair specific sensory modalities.

- Proprioception (Joint Position Sense): The unconscious perception of movement and spatial orientation, derived from stimuli within the body itself. Loss leads to a feeling of unsteadiness, especially in the dark or when eyes are closed (sensory ataxia, positive Romberg sign). Often due to damage to dorsal columns of the spinal cord (e.g., B12 deficiency, tabes dorsalis) or large fiber peripheral neuropathies.

- Vibration Sense: Sensation perceived through a vibrating tuning fork. Loss often parallels proprioceptive loss and indicates damage to dorsal columns or large fiber peripheral nerves.

- Temperature Sense: Ability to distinguish hot from cold. Loss suggests damage to the spinothalamic tract (e.g., syringomyelia, brainstem lesion, small fiber neuropathy).

- Light Touch: Ability to perceive gentle contact. Loss can occur with damage to various sensory pathways.

- Two-Point Discrimination: The ability to discern two distinct points of contact on the skin. Impaired in parietal lobe lesions or severe peripheral neuropathy.

5. Visual Disturbances

The visual system is an extension of the CNS, making visual symptoms highly informative.

- Monocular Diplopia: Double vision present when only one eye is open. Usually an ophthalmological problem (e.g., cataract, corneal abnormality).

- Binocular Diplopia: Double vision that disappears when either eye is closed. Always indicates a neurological problem, usually involving weakness or misalignment of the extraocular muscles due to:

- Cranial Nerve Palsies: Damage to CN III (Oculomotor), CN IV (Trochlear), or CN VI (Abducens).

- Neuromuscular Junction Disorders: Myasthenia gravis.

- Brainstem Lesions: Affecting the nuclei or pathways of these cranial nerves.

- Monocular Vision Loss: Loss of vision in one eye. Points to a lesion anterior to the optic chiasm (e.g., optic nerve, retina).

- Binocular Vision Loss: Loss of vision affecting both eyes. The pattern is crucial:

- Bitemporal Hemianopsia: Loss of vision in the outer half of both visual fields (tunnel vision). Caused by compression of the optic chiasm (e.g., pituitary tumor).

- Homonymous Hemianopsia: Loss of vision in the same half of the visual field in both eyes (e.g., right visual field loss in both eyes). Caused by a lesion posterior to the optic chiasm in the contralateral optic tract, optic radiations, or visual cortex (e.g., stroke, tumor).

- Quadrantanopsia: Loss of vision in one quadrant of the visual field.

6. Hearing and Vestibular Disturbances

Involvement of the eighth cranial nerve (vestibulocochlear) or its central connections.

- Peripheral Vertigo: Originates from the inner ear or vestibular nerve (e.g., Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo - BPPV, Meniere's disease, vestibular neuritis). Often sudden onset, severe, associated with nausea/vomiting, specific types of nystagmus, and sometimes hearing changes.

- Central Vertigo: Originates from the brainstem or cerebellum (e.g., stroke, multiple sclerosis, tumor). Often less severe, more persistent, vague unsteadiness, different types of nystagmus (pure vertical nystagmus is always central), and may be associated with other brainstem signs.

Learning Objective 5: Discuss cognitive and higher cortical function deficits commonly seen in neurological diseases.

Cognitive functions encompass all mental processes involved in knowing, perceiving, remembering, and thinking. Higher cortical functions specifically refer to complex processes like language, executive function, and praxis. Deficits in these areas profoundly impact an individual's quality of life and independence, and their presence points to pathology within the cerebral hemispheres, particularly the cortex and subcortical structures involved in these processes.

1. Memory Impairment

Memory loss is one of the most common and distressing cognitive symptoms.

- Anterograde Amnesia: Difficulty forming new memories after the onset of the condition. Patients cannot recall events that occurred hours or days ago. This is characteristic of hippocampal damage (e.g., Alzheimer's disease in its early stages, severe anoxia, herpes encephalitis).

- Retrograde Amnesia: Difficulty recalling past events or information that occurred before the onset of the condition. The extent can vary, often showing a temporal gradient (recent memories more affected than remote ones). Seen in conditions affecting temporal lobes and diffuse brain injury.

- Working Memory Deficits: Difficulty holding and manipulating information in mind for a short period (e.g., trouble remembering a phone number just heard). Reflects dysfunction in frontal lobe executive systems.

- Semantic Memory Impairment: Difficulty recalling factual knowledge (e.g., names of presidents, capitals of countries).

- Episodic Memory Impairment: Difficulty recalling specific personal events or experiences.

- Confabulation: The production of fabricated, distorted, or misinterpreted memories about oneself or the world, without the conscious intention to deceive. Often seen in Korsakoff's syndrome (due to thiamine deficiency, common in chronic alcoholism) or frontal lobe damage.

2. Language Disorders (Aphasias)

Aphasia is an impairment of language, affecting the production or comprehension of speech and the ability to read or write, caused by damage to specific brain regions, typically in the dominant (usually left) cerebral hemisphere.

- Site of Lesion: Posterior inferior frontal lobe (Broca's area).

- Characteristics: Speech is labored, hesitant, and sparse, often described as "telegraphic." Patients struggle to produce words, but comprehension is relatively preserved. Repetition is poor. Writing is often affected.

- Site of Lesion: Posterior superior temporal lobe (Wernicke's area).

- Characteristics: Speech is fluent and copious but often meaningless ("word salad"). Patients have severe difficulty understanding spoken and written language. Repetition is poor. They are often unaware of their deficit.

- Site of Lesion: Arcuate fasciculus (connects Broca's and Wernicke's areas).

- Characteristics: Fluent speech, relatively good comprehension, but severe difficulty repeating words or phrases.

- Site of Lesion: Large lesion encompassing both Broca's and Wernicke's areas.

- Characteristics: Severe impairment of all language modalities: speaking, understanding, reading, and writing.

- Site of Lesion: Can be diffuse or specific to angular gyrus.

- Characteristics: Primary difficulty is word-finding (anomia), especially for nouns. Other language functions are relatively preserved.

3. Executive Dysfunction

These are deficits in higher-level cognitive processes responsible for goal-directed behavior. They are typically associated with damage to the frontal lobes.

- Planning and Problem Solving: Inability to formulate, initiate, and sequence steps to achieve a goal.

- Working Memory: Difficulty holding and manipulating information for complex tasks.

- Inhibition: Difficulty suppressing inappropriate behaviors or thoughts (e.g., disinhibition, impulsivity).

- Flexibility (Set-Shifting): Inability to switch between different tasks or mental sets.

- Abstract Reasoning: Difficulty understanding concepts beyond their literal meaning.

- Decision Making: Impaired judgment.

- Initiation: Apathy, lack of motivation to start tasks.

4. Neglect Syndromes (Hemineglect)

- Definition: A disorder of attention where a patient fails to report, respond to, or orient to novel or meaningful stimuli presented to the side opposite a brain lesion, without this failure being due to primary sensory or motor deficit.

- Site of Lesion: Most commonly seen with lesions of the right parietal lobe, leading to left-sided neglect (e.g., patient only dresses one side of their body, eats only half their plate, ignores people on their left). It's a disorder of spatial attention, not just vision.

5. Agnosias

- Visual Agnosia: Inability to recognize objects by sight. Often due to damage in the occipital and temporal lobes.

- Prosopagnosia (Facial Agnosia): Inability to recognize familiar faces, including one's own. Lesion in the fusiform gyrus (often right-sided).

- Auditory Agnosia: Inability to recognize sounds.

- Tactile Agnosia (Astereognosis): Inability to recognize objects by touch, despite intact touch and proprioception. Lesion in the parietal lobe.

6. Apraxias

- Ideomotor Apraxia: Inability to imitate gestures or perform purposeful motor tasks on command (e.g., "show me how you brush your teeth"). Patients often know what they want to do but cannot execute the movement. Lesions often in left parietal lobe or corpus callosum.

- Ideational Apraxia: Inability to perform a sequence of motor acts towards a goal (e.g., cannot sequence the steps to make a cup of coffee). More severe, often seen in dementia or widespread cortical damage.

- Constructional Apraxia: Difficulty copying, drawing, or constructing simple figures or designs (e.g., inability to draw a clock face). Associated with parietal lobe lesions, particularly right parietal.

- Gait Apraxia: Inability to walk or initiate walking, despite normal leg strength and coordination when lying down. Often associated with frontal lobe pathology (e.g., Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus).

7. Other Cognitive Symptoms

- Disorientation: Confusion regarding time, place, or person.

- Attention Deficits: Difficulty sustaining attention, easily distracted.

- Confabulation: As mentioned under memory, creating false memories without intention to deceive.

- Apathy: Lack of interest, enthusiasm, or concern.

- Disinhibition: Inability to control impulses, leading to inappropriate social behavior.

- Perseveration: Inappropriate repetition of a word, thought, or act.

Learning Objective 6: Outline the spectrum of autonomic nervous system dysfunction and its clinical manifestations.

The autonomic nervous system (ANS) controls involuntary bodily functions vital for life, such as heart rate, blood pressure, digestion, temperature regulation, and bladder function. Dysfunction of the ANS can manifest in a wide array of symptoms, often affecting multiple organ systems, and can range from uncomfortable to life-threatening.

1. Orthostatic Hypotension

- Definition: A fall in blood pressure that occurs when a person stands up from a sitting or lying position. Specifically, a drop of ≥ 20 mmHg in systolic BP or ≥ 10 mmHg in diastolic BP within 3 minutes of standing.

- Symptoms: Dizziness, lightheadedness, weakness, visual blurring, presyncope (feeling faint), or syncope (fainting) upon standing.

- Causes: Damage to the ANS (e.g., Parkinson's disease, multiple system atrophy, pure autonomic failure, diabetic neuropathy, amyloidosis), certain medications, dehydration.

2. Bladder Dysfunction

- Neurogenic Bladder: Impaired bladder control due to neurological damage.

- Urgency/Frequency/Incontinence: Often seen with upper motor neuron lesions (e.g., stroke, multiple sclerosis, spinal cord injury above sacral levels). The bladder detrusor muscle becomes hyperactive.

- Hesitancy/Retention/Overflow Incontinence: Often seen with lower motor neuron lesions (e.g., cauda equina syndrome, diabetic neuropathy, sacral spinal cord injury). The bladder muscle is flaccid and underactive, leading to incomplete emptying and overflow.

3. Bowel Dysfunction

- Constipation: A very common autonomic symptom, especially in conditions like Parkinson's disease and diabetic neuropathy, due to reduced gut motility.

- Fecal Incontinence: Can occur with severe LMN lesions affecting the sacral nerves.

4. Sexual Dysfunction

- Erectile Dysfunction (ED) in Men: Common in neurological disorders affecting the ANS (e.g., diabetic neuropathy, multiple sclerosis, spinal cord injury).

- Decreased Libido and Arousal Difficulties in Women: Also associated with ANS dysfunction.

5. Sweating Abnormalities (Sudomotor Dysfunction)

- Anhidrosis: Absent sweating. Can lead to heat intolerance. Often seen in peripheral neuropathies and conditions causing localized sympathetic denervation (e.g., Horner's syndrome).

- Hyperhidrosis: Excessive sweating. Less commonly a primary neurological symptom but can be associated with certain conditions or medications.

- Harlequin Syndrome: Asymmetric facial flushing and sweating on one side of the face, usually contralateral to a lesion, indicating sympathetic denervation on one side.

6. Pupillary Abnormalities

The pupils are controlled by both sympathetic and parasympathetic systems.

- Horner's Syndrome: Triad of ptosis (drooping eyelid), miosis (constricted pupil), and anhidrosis (absence of sweating) on one side of the face. Caused by interruption of the sympathetic pathway (e.g., stroke in brainstem, cervical spinal cord lesion, Pancoast tumor in lung apex).

- Adie's Pupil: A unilaterally dilated pupil that reacts poorly to light but constricts slowly on convergence. Often benign, but indicates parasympathetic denervation.

- Argyll Robertson Pupil: Small, irregular pupils that accommodate (constrict on near vision) but do not react to light. A classic sign of neurosyphilis.

7. Thermoregulatory Dysfunction

- Poikilothermia: Inability to maintain a stable core body temperature, leading to body temperature fluctuations with environmental changes. Can occur with severe hypothalamic damage or high spinal cord lesions.

8. Cardiovascular Autonomic Dysfunction

- Heart Rate Variability Impairment: Reduced beat-to-beat variation in heart rate, indicating general autonomic dysfunction.

- Supine Hypertension: High blood pressure while lying down, paradoxically coexisting with orthostatic hypotension in some autonomic disorders (e.g., multiple system atrophy).

Learning Objective 7: Describe psychiatric and general symptoms that may indicate neurological disease.

Neurological diseases can significantly impact mood, behavior, and psychological function, sometimes even preceding the more overt physical symptoms. Recognizing these psychiatric manifestations as potential signs of neurological disease is crucial for early diagnosis and intervention. Additionally, several general symptoms, while non-specific, can frequently accompany neurological conditions.

1. Mood Disorders

- Depression: Extremely common in neurological diseases, often due to direct brain changes (e.g., in stroke, Parkinson's disease, Alzheimer's disease, multiple sclerosis), chronic pain, or the psychological burden of living with a chronic illness. Can manifest as persistent sadness, anhedonia (loss of pleasure), fatigue, changes in appetite/sleep, and feelings of worthlessness.

- Anxiety: Frequent in conditions like epilepsy, stroke, dementia, and Parkinson's disease. Can be generalized, manifested as panic attacks, or specific phobias.

- Mania/Hypomania: Less common, but can occur in certain neurological conditions, especially those affecting the frontal or temporal lobes (e.g., right-sided stroke, traumatic brain injury, multiple sclerosis, some dementias).

2. Psychotic Symptoms

- Hallucinations: Perceptions in the absence of an external stimulus (e.g., visual hallucinations in Parkinson's disease, auditory hallucinations in temporal lobe epilepsy or dementias with Lewy bodies).

- Delusions: Fixed, false beliefs that are not amenable to change in light of conflicting evidence. Can be seen in various dementias, advanced Parkinson's disease, and some forms of epilepsy.

3. Behavioral Changes

- Apathy and Abulia: A lack of motivation, interest, or concern. Abulia is a more severe form of apathy, characterized by extreme slowness in initiating and executing movements and speech. Often seen with frontal lobe damage (e.g., stroke, dementia, traumatic brain injury).

- Disinhibition: Loss of impulse control, leading to socially inappropriate behavior, irritability, and impulsivity. Commonly associated with frontal lobe damage (e.g., frontotemporal dementia, traumatic brain injury).

- Irritability and Aggression: Can be a prominent symptom in various neurological conditions, including dementia, traumatic brain injury, and temporal lobe epilepsy.

- Personality Changes: Marked shifts in usual personality traits. This can be an early and prominent symptom in certain dementias (e.g., frontotemporal dementia).

4. Sleep Disturbances

Sleep architecture is intricately linked to brain function, and neurological disorders frequently disrupt sleep.

- Insomnia: Difficulty falling or staying asleep. Very common in chronic pain syndromes, Parkinson's disease, restless legs syndrome, and depression.

- Hypersomnia: Excessive daytime sleepiness. Can be a symptom of conditions like narcolepsy, sleep apnea (though not directly neurological in origin, its consequences impact the brain), or hypothalamic lesions.

- REM Sleep Behavior Disorder (RBD): Acting out dreams during REM sleep due to loss of normal muscle atonia. Strongly associated with synucleinopathies like Parkinson's disease and multiple system atrophy, often preceding motor symptoms by years.

- Restless Legs Syndrome (RLS): An irresistible urge to move the legs, usually accompanied by uncomfortable sensations, worse at rest and in the evening. Can be primary or secondary to conditions like iron deficiency, kidney failure, or peripheral neuropathy.

5. Fatigue

- Definition: A pervasive sense of tiredness, low energy, and feeling drained, not relieved by rest. It is a common and often debilitating symptom in many neurological conditions.

- Causes: A prominent symptom in multiple sclerosis, Parkinson's disease, post-stroke, chronic pain syndromes, and traumatic brain injury. It can be due to direct central nervous system damage, chronic inflammation, medication side effects, or secondary to sleep disturbances and depression.

6. Headache and Facial Pain (Revisited as General Symptom)

While discussed under sensory symptoms (Objective 4), headaches are so pervasive that they warrant mention as a general symptom. Persistent, new-onset, or severe headaches always require evaluation to rule out underlying neurological pathology.

- Types: Tension, migraine, cluster, secondary headaches (e.g., from increased intracranial pressure, brain tumors, meningitis).

- Red Flags: Acute onset "thunderclap" headache, headache with fever/stiff neck, focal neurological deficits, papilledema, headache worsening with position changes (suggesting CSF leak or pressure issues).

7. Weight Changes

- Weight Loss: Can occur in advanced neurological diseases due to dysphagia, loss of appetite, increased metabolic demands (e.g., ALS), or the underlying disease process itself.

- Weight Gain: Less common, but certain conditions or medications (e.g., some antipsychotics, hypothalamic lesions) can lead to weight gain.

8. Fever and Chills

- Neurological Fever: Fever can be a primary neurological symptom if the hypothalamus (the brain's thermoregulatory center) is damaged (e.g., stroke, tumor).

- Infection: More commonly, fever in a neurological context indicates an infection of the nervous system (e.g., meningitis, encephalitis, brain abscess) or a systemic infection affecting a neurologically vulnerable patient.

Learning Objective 8: Understand the various types of seizures and their clinical presentations.

Seizures are transient occurrences of signs and/or symptoms due to abnormal excessive or synchronous neuronal activity in the brain. Epilepsy is a disease characterized by an enduring predisposition to generate epileptic seizures and by the neurobiologic, cognitive, psychological, and social consequences of this condition.

1. Classification of Seizures (ILAE 2017)

The classification is based on:

- Where seizures begin in the brain: Focal or Generalized.

- Level of awareness during a focal seizure: Aware or Impaired Awareness.

- Other features: Motor or non-motor onset.

- When necessary, the presence of bilateral tonic-clonic activity.

2. Focal Seizures

Originate in one area of the brain.

- Awareness: Intact awareness during the seizure.

- Symptoms: Vary depending on the brain region affected. Can include:

- Motor: Twitching, jerking, stiffening of a limb or one side of the face (e.g., Jacksonian march if it spreads).

- Sensory: Tingling, numbness, visual disturbances (flashing lights, formed hallucinations), auditory hallucinations (ringing, music), olfactory hallucinations (unusual smells), gustatory hallucinations (unusual tastes).

- Autonomic: Pallor, flushing, sweating, piloerection, epigastric rising sensation, tachycardia.

- Psychic: Deja vu, jamais vu, fear, anxiety, pleasure, emotional changes.

- Awareness: Impaired awareness (not necessarily unconsciousness) at some point during the seizure. The patient may appear "zoned out," staring blankly.

- Symptoms: Often begin with an aura (a focal aware seizure preceding the impaired awareness). Characterized by automatisms – repetitive, non-purposeful behaviors such as lip-smacking, chewing, fidgeting, picking at clothes, walking aimlessly, mumbling. After the seizure, there is often a post-ictal confusion (period of drowsiness, confusion, and memory loss) lasting minutes to hours.

- Most common origin: Temporal lobe, but can originate elsewhere.

- A focal seizure that spreads to involve both hemispheres, resulting in a generalized tonic-clonic seizure.

3. Generalized Seizures

Originate at some point in the brain and rapidly engage bilaterally distributed networks. Awareness is always impaired.

- Tonic Phase: Sudden loss of consciousness, body stiffens (tonic contraction of muscles), often with an epileptic cry (air forced out of lungs), patient falls. Breathing may stop, skin may turn blue. Lasts seconds to a minute.

- Clonic Phase: Rhythmic jerking of the limbs (clonic contractions) typically lasting minutes. Tongue biting, urinary incontinence are common.

- Post-ictal Phase: Prolonged period of deep sleep, confusion, headache, muscle aches, and fatigue.

- Characteristics: Brief (usually 5-10 seconds, rarely >20 seconds) episodes of sudden impairment of consciousness, often with a blank stare, eye fluttering, or brief automatisms. No post-ictal confusion. The patient is unaware of the seizure. They can occur many times a day and impair learning.

- Common in childhood.

- Characteristics: Brief, shock-like jerks of a muscle or group of muscles. Can be generalized or focal. Often occur upon waking up. Consciousness is usually preserved unless severe or multiple jerks occur.

- Characteristics: Sudden loss of muscle tone, leading to a sudden fall (head drop, or collapse of the entire body). Very brief (seconds), consciousness is usually regained quickly. High risk of injury.

- Characteristics: Sustained stiffening of muscles, similar to the tonic phase of a tonic-clonic seizure but without the subsequent clonic phase. Typically brief, often seen in sleep.

- Characteristics: Rhythmic jerking movements, similar to the clonic phase of a tonic-clonic seizure but without the initial tonic phase. Rarity in adults.

4. Status Epilepticus

- Definition: A medical emergency defined as a seizure lasting longer than 5 minutes, or recurrent seizures without recovery of consciousness between them. Requires immediate medical intervention due to risk of permanent brain damage or death.

5. Provoked Seizures

Seizures that occur in response to an acute brain insult (e.g., acute stroke, head trauma, severe electrolyte disturbance, drug overdose/withdrawal, acute infection). These are not considered epilepsy unless there is an enduring predisposition to future seizures.

Learning Objective 9: Describe the systematic approach to the neurological physical examination.

A neurological examination is a systematic assessment of the nervous system performed by a neurologist or other medical professional. It is structured to evaluate various components of the central and peripheral nervous systems to localize pathology and determine its nature. A systematic approach ensures no important aspect is missed.

1. Mental Status Examination

This is often the first part of the neurological exam, assessing cognitive function and emotional state. It helps evaluate the presence and severity of cognitive deficits discussed in Objective 5.

- Immediate Recall: Repeat 3-5 words immediately.

- Recent Memory: Recall those words after 5 minutes.

- Remote Memory: Ask about well-known historical facts or personal past events.

- Fluency: Observe spontaneous speech (rate, rhythm, effort).

- Comprehension: Follow 1-, 2-, and 3-step commands.

- Naming: Name objects shown.

- Repetition: Repeat words/phrases.

- Reading/Writing: Ask patient to read a sentence and write one.

2. Cranial Nerve Examination (CN I-XII)

Tests the function of the 12 cranial nerves, which innervate structures of the head and neck and carry sensory information from these areas. Damage to specific cranial nerves can localize lesions to the brainstem or specific peripheral nerves.

- Visual Acuity: Snellen chart (distance), reading card (near).

- Visual Fields: Confrontation testing (patient and examiner compare fields).

- Fundoscopy: Examine optic disc for papilledema (swelling) or atrophy.

- Pupillary Light Reflex: Direct and consensual (CN II afferent, CN III efferent).

- Extraocular Movements (EOMs): Test all 6 cardinal gazes (H-pattern). Look for diplopia, nystagmus, limitation of movement.

- Pupillary Size/Shape/Reactivity: Direct and consensual light reflex (CN III efferent). Accommodation (CN III).

- Lid Ptosis: Drooping of the eyelid (CN III lesion, Horner's).

- Sensory: Test light touch, pinprick, and temperature in all three divisions (ophthalmic, maxillary, mandibular) on both sides of the face.

- Motor: Palpate temporalis and masseter muscles while patient clenches jaw. Test jaw opening and movement against resistance.

- Corneal Reflex: Touch cornea with cotton wisp (CN V afferent, CN VII efferent).

- Motor: Ask patient to raise eyebrows, close eyes tightly (against resistance), smile, frown, show teeth, puff cheeks. Observe for asymmetry.

- Taste (anterior 2/3 tongue): (Often omitted).

- Auditory: Whisper test, Weber (lateralization), Rinne (bone vs. air conduction) tests.

- Vestibular: Observe for nystagmus, assess balance (Romberg test), inquire about vertigo.

- Phonation: Listen to voice (hoarseness, dysphonia).

- Swallowing: Ask patient to swallow water (observe for dysphagia).

- Palatal Movement: Ask patient to say "Ah," observe symmetrical soft palate elevation and uvula deviation.

- Gag Reflex: (CN IX afferent, CN X efferent) (Often omitted unless indicated).

- Motor: Test sternocleidomastoid (turn head against resistance) and trapezius (shrug shoulders against resistance) strength.

- Motor: Inspect tongue in mouth for atrophy/fasciculations. Ask patient to protrude tongue (observe for deviation). Ask patient to move tongue side-to-side.

3. Motor System Examination

Evaluates muscle bulk, tone, strength, and coordination. Correlates with symptoms discussed in Objective 3.

- Passively move limbs through full range of motion. Assess for hypotonia (flaccidity), hypertonia (spasticity, rigidity, paratonia).

- Test key muscles in upper and lower limbs against resistance.

- 0: No contraction.

- 1: Flicker or trace of contraction.

- 2: Active movement, gravity eliminated.

- 3: Active movement against gravity.

- 4: Active movement against gravity and some resistance.

- 5: Normal strength.

- Test specific movements: shoulder abduction (deltoid), elbow flexion (biceps), elbow extension (triceps), wrist extension/flexion, finger abduction/adduction, hip flexion (iliopsoas), knee extension (quadriceps), knee flexion (hamstrings), ankle dorsiflexion/plantarflexion.

- Look for patterns of weakness (proximal/distal, hemiparesis, paraparesis, etc.).

- Finger-to-Nose Test: Rapidly and accurately touch examiner's finger then own nose. Look for dysmetria (inaccurate movement), intention tremor.

- Heel-to-Shin Test: Patient drags heel down opposite shin. Look for dysmetria.

- Rapid Alternating Movements: Tap palm quickly on thigh, pronate/supinate hands rapidly. Look for dysdiadochokinesia (impaired rapid alternating movements).

4. Reflex Examination

Evaluates both deep tendon reflexes (DTRs) and superficial reflexes.

- 0: Absent.

- 1+: Diminished, hypoactive.

- 2+: Average, normal.

- 3+: Brisker than average, possibly but not necessarily abnormal.

- 4+: Hyperactive, with clonus (rhythmic oscillation when limb is stretched).

- Upper Limbs: Biceps (C5-C6), Triceps (C6-C7), Brachioradialis (C5-C6).

- Lower Limbs: Patellar (L2-L4), Achilles (S1).

- Significance:

- Hyporeflexia/Areflexia (0, 1+): Suggests Lower Motor Neuron (LMN) lesion (e.g., peripheral neuropathy, nerve root compression) or muscle disease.

- Hyperreflexia (3+, 4+ with clonus): Suggests Upper Motor Neuron (UMN) lesion (e.g., stroke, spinal cord injury, MS).

- Plantar Reflex (Babinski Sign): Stroke lateral sole of foot from heel to toes. Normal response is downward flexion of toes. Extensor plantar response (upward extension of great toe, fanning of other toes) is a pathological sign of UMN lesion (except in infants).

- Abdominal Reflexes: Stroke abdomen in four quadrants. Normal response is contraction of abdominal wall. (May be absent in UMN lesions or obesity).

- Cremasteric Reflex: Stroke inner thigh. Normal response is ipsilateral testicular elevation. (Absent in LMN lesions of L1-L2).

5. Sensory System Examination

Evaluates different sensory modalities, correlating with symptoms from Objective 4. Patterns of sensory loss are key for localization.

- Stereognosis: Identify familiar objects by touch with eyes closed.

- Graphesthesia: Identify numbers/letters written on palm with eyes closed.

- Two-point Discrimination: Distinguish one vs. two points touched.

- Extinction: Touch two symmetrical body parts simultaneously. Patient should feel both. If one is ignored (extinguished), suggests contralateral parietal lobe lesion.

- Point Localization: Patient closes eyes, examiner touches skin, patient points to spot.

6. Gait and Station Examination

Observes how the patient stands and walks, looking for specific abnormalities (Objective 3).

- Observe posture, base of support.

- Romberg Test: Patient stands with feet together, eyes open, then closes eyes.

- Positive Romberg: Worsening instability with eyes closed, indicating sensory ataxia (proprioceptive loss, dorsal columns).

- Negative Romberg: Stability remains similar with eyes open/closed, but may still be unsteady due to cerebellar ataxia.

- Ask patient to walk normally, heel-to-toe (tandem), on heels, on toes.

- Observe for:

- Width of base: Wide (ataxia, sensory loss) vs. narrow (spasticity).

- Arm swing: Reduced/absent (Parkinsonian).

- Stride length: Short, shuffling (Parkinsonian) vs. long, exaggerated (ataxic).

- Foot clearance: Foot drop (steppage gait), circumduction (hemiparesis).

- Balance: Unsteadiness, staggering.

- Turning: En bloc (Parkinsonian).

Learning Objective 10: Differentiate between pyramidal, extrapyramidal, and cerebellar signs.

These three categories represent distinct neurological systems responsible for motor control and coordination. Identifying which set of signs predominates in a patient is critical for localizing the lesion and narrowing down the differential diagnosis.

1. Pyramidal Signs (Upper Motor Neuron (UMN) Lesion Signs)

The pyramidal tract (corticospinal tract) originates in the cerebral cortex and descends to the spinal cord, responsible for voluntary, skilled movements. Damage to this pathway, anywhere from the cortex down to the anterior horn cell (but before the peripheral nerve), results in UMN signs.

- Upper Limb: Extensors weaker than flexors (arm held in flexion, often pronated).

- Lower Limb: Flexors weaker than extensors (leg held in extension).

- Definition: Velocity-dependent increase in muscle tone, resistance to passive movement that is greatest at the beginning of the movement ("clasp-knife" phenomenon).

- Mechanism: Due to hyperexcitability of the stretch reflex.

- Definition: Rhythmic, involuntary muscle contractions and relaxations, often elicited by a sustained stretch of the muscle (e.g., ankle clonus by brisk dorsiflexion of the foot). Indicates severe hyperreflexia.

- Definition: When the lateral sole of the foot is stroked, the great toe extends upwards (dorsiflexion) and the other toes fan out.

- Significance: A pathological reflex, almost always indicative of UMN dysfunction (except in infants).

2. Extrapyramidal Signs

The extrapyramidal system refers to neural networks involved in the modulation and coordination of movement, largely through connections in the basal ganglia (substantia nigra, striatum, globus pallidus, subthalamic nucleus). Dysfunction here leads to a different constellation of motor symptoms.

- Definition: Increased resistance to passive movement that is independent of velocity throughout the range of motion.

- Types:

- Lead-pipe rigidity: Constant resistance throughout the movement.

- Cogwheel rigidity: Intermittent catches or "ratchety" sensation during passive movement, often seen with tremor.

- Bradykinesia: Slowness of movement.

- Akinesia: Absence of movement, difficulty initiating movement.

- Manifestations: Reduced facial expression (mask-like face), decreased blink rate, reduced arm swing during gait, difficulty with fine motor tasks (e.g., writing gets smaller - micrographia).

- Resting Tremor: Occurs when the limb is at rest and disappears or significantly reduces with voluntary movement (e.g., "pill-rolling" tremor of Parkinson's disease).

- Definition: Sustained or intermittent muscle contractions causing abnormal, often repetitive, movements and/or postures (e.g., torticollis, blepharospasm).

- Definition: Irregular, unpredictable, involuntary, brief, jerky movements that flow from one body part to another (e.g., Huntington's disease).

- Definition: Slow, writhing, involuntary movements, often affecting distal limbs, face, and trunk.

- Definition: Large-amplitude, flinging, involuntary movements of the limb, often unilateral (hemiballism) due to subthalamic nucleus lesion.

- Definition: Sudden, rapid, recurrent, non-rhythmic motor movements or vocalizations (e.g., Tourette's syndrome).

3. Cerebellar Signs

The cerebellum is crucial for coordinating voluntary movements, maintaining balance, and regulating muscle tone. Lesions here affect movement smoothness, accuracy, and timing, rather than causing primary weakness.

- Definition: Impairment of coordination, characterized by jerky, unsteady movements.

- Truncal Ataxia: Difficulty maintaining an upright posture, wide-based, unsteady gait. Suggests midline cerebellar lesion (e.g., vermis).

- Appendicular Ataxia: Incoordination of limb movements (e.g., dysmetria, dysdiadochokinesia). Suggests lateral cerebellar hemisphere lesion.

- Definition: Inability to accurately estimate the range of motion necessary to reach a target. Patients will either under-shoot (hypometria) or over-shoot (hypermetria) their target (e.g., during finger-to-nose or heel-to-shin test).

- Definition: Impairment in the ability to perform rapid alternating movements (e.g., rapidly pronating and supinating hands, tapping foot). Movements become irregular and clumsy.

- Definition: Tremor that appears or worsens during voluntary movement, especially as the limb approaches a target (e.g., while reaching for a cup). Absent at rest. Distinct from the resting tremor of Parkinson's.

- Definition: Involuntary, rhythmic oscillation of the eyeballs. Cerebellar nystagmus is often gaze-evoked, coarser, and can be in any direction.

- Definition: Slurred, scanning, or "drunken" speech. Characterized by abnormal articulation, phonation, and prosody.

- Definition: Decreased muscle tone. Limbs may feel "floppy." Pendular reflexes (limbs swing like a pendulum after reflex elicitation) can be a sign.

General signs and symptoms of the nervous system disorders Read More »