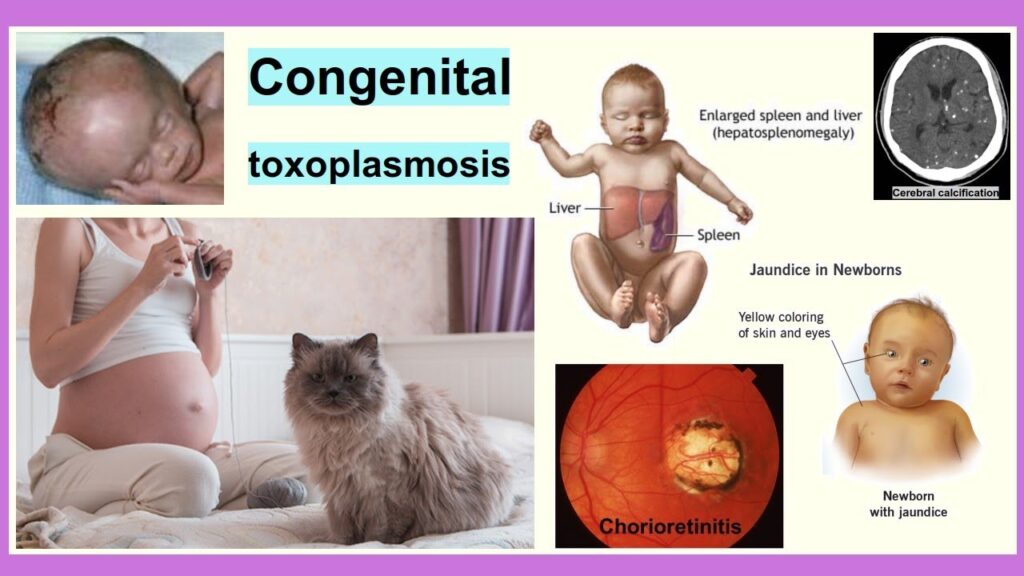

Congenital toxoplasmosis is a disease that occurs in fetuses or new-borns infected with Toxoplasma gondii, a protozoan parasite, which is transmitted from mother to fetus.

Congenital Toxoplasmosis is an infection of a fetus or newborn baby with the parasite Toxoplasma gondii, acquired in utero from an infected mother.

- Toxoplasma gondii is an obligate intracellular protozoan parasite. This means it can only reproduce inside the cells of a host.

- It belongs to the phylum Apicomplexa, a group of parasites that includes other well-known pathogens like Plasmodium (malaria) and Cryptosporidium.

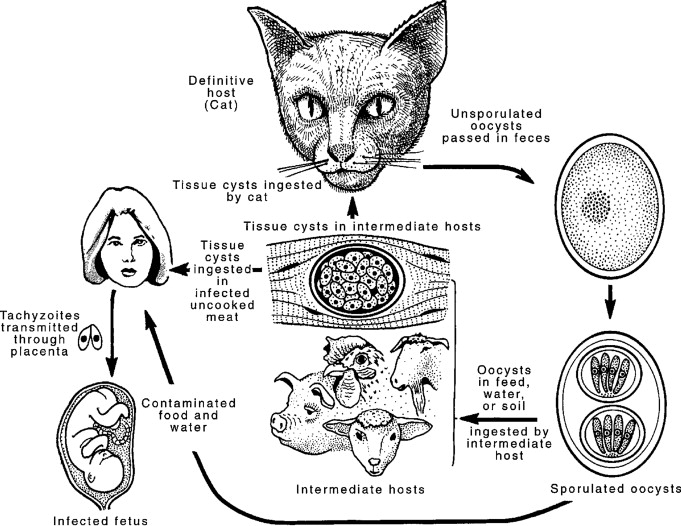

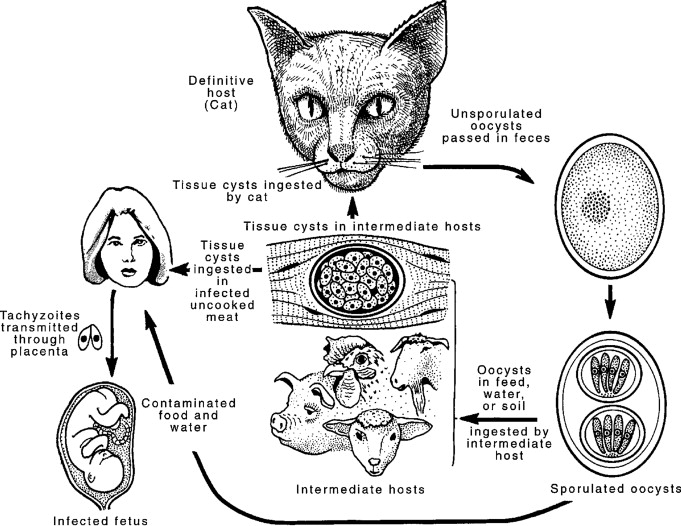

Congenital toxoplasmosis occurs when Toxoplasma gondii is transmitted from a pregnant woman to her fetus through the placenta, resulting from a primary maternal infection during or shortly before pregnancy. While the infection in the mother can be acquired via three different forms, the parasite reaches the fetus primarily as tachyzoites.

The infectious forms of T. gondii that initiate the maternal infection (leading to the subsequent vertical transmission) are:

- This is the fast-dividing, crescent-shaped, actively multiplying form.

- In the context of congenital toxoplasmosis, the parasite multiplies in the mother's placenta and enters the fetal circulation in this stage.

- Tachyzoites are responsible for direct, acute tissue damage.

- They are the form typically transmitted across the placenta to the fetus.

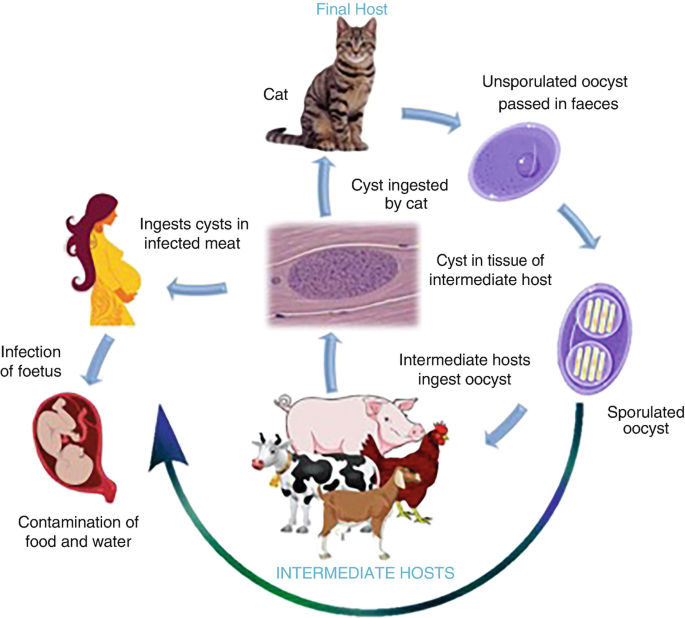

- These are slow-multiplying organisms found within tissue cysts in the meat of intermediate hosts.

- Ingestion of undercooked or raw meat (especially pork, lamb, or venison) containing these cysts is a primary way pregnant women become infected.

- Once ingested, the cyst walls are broken down by stomach acid, releasing the bradyzoites, which then transform into tachyzoites.

- These are contained within oocysts that are produced in the intestines of cats (the definitive host) and excreted in their feces.

- The oocysts require 1–5 days to sporulate and become infectious in the environment.

- Ingestion of food, water, or soil contaminated with sporulated oocysts (e.g., via unwashed vegetables or handling contaminated cat litter) causes infection in humans.

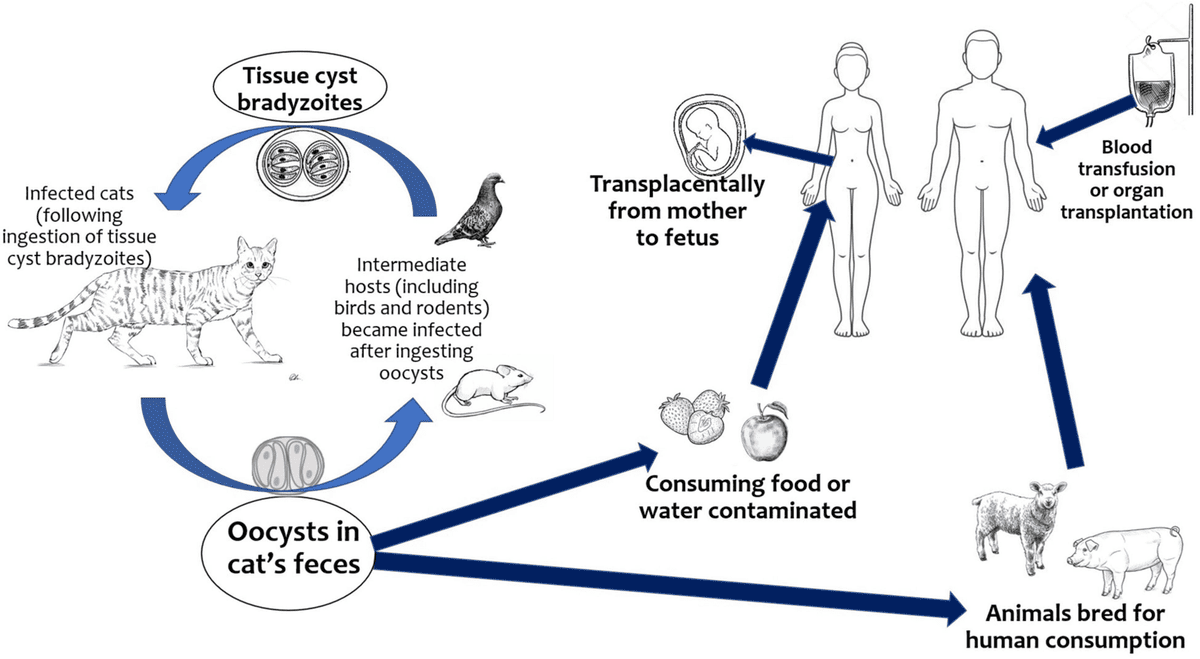

- Toxoplasma gondii has a complex life cycle involving definitive hosts (domestic and wild cats) and intermediate hosts (virtually all warm-blooded animals, including humans, birds, and other mammals).

- In cats (definitive host): The parasite undergoes sexual reproduction in the feline intestine, producing oocysts that are shed in the cat's feces. These oocysts sporulate and become infective in the environment within 1-5 days.

- In intermediate hosts (including humans):

- When an intermediate host ingests sporulated oocysts (e.g., from contaminated soil, water, unwashed vegetables) or tissue cysts (e.g., from undercooked meat of infected animals), the parasites are released.

- They rapidly multiply as tachyzoites (the rapidly multiplying, invasive form) which disseminate throughout the body via the bloodstream and lymphatic system.

- The immune system eventually controls the tachyzoites, which then transform into slower-growing bradyzoites contained within tissue cysts, primarily in muscle, brain, and eye tissues. These tissue cysts can persist for the life of the host and are responsible for chronic, latent infection.

- Eating undercooked or raw meat (especially pork, lamb, venison) containing Toxoplasma tissue cysts. This is a very common route.

- Ingesting sporulated oocysts from contaminated sources (e.g., unwashed fruits/vegetables from contaminated soil, contaminated water).

- Changing cat litter boxes without proper hygiene.

- Gardening or playing in areas contaminated with cat feces.

- This is the focus of congenital toxoplasmosis. A pregnant woman who acquires a primary infection with Toxoplasma gondii during pregnancy can transmit the parasite transplacentally to her fetus.

- Foodborne: Humans can contract toxoplasmosis by eating undercooked meat containing infective tissue forms of the parasite T. gondii. It can also be transferred to food and therefore to humans through contaminated utensils and cutting boards. Also, drinking unpasteurized goat’s milk can cause toxoplasmosis infection.

- Zoonotic transmission: Zoonotic transmission refers to animal to human transfer of the infection. Cats play a major role in this type of transmission. Cats serve as hosts to T. gondii. They shed their oocysts through their feces, and these oocysts are microscopic and can be transferred to humans through accidental ingestion by not washing hands after cleaning the cat’s litter box, drinking water infected with oocysts, or not using gloves when gardening.

- Rare means of transmission: In very rare occasions, toxoplasmosis can be transmitted through organ donation and transplant, as well as in blood transfusion.

- Consumption of raw or undercooked meat (especially pork, lamb, venison) containing tissue cysts is a major risk factor.

- Eating unwashed fruits or vegetables contaminated with oocysts.

- Contact with soil contaminated with cat feces (e.g., gardening without gloves, playing in sandboxes where cats defecate).

- Cleaning cat litter boxes (especially if done frequently, without gloves, and without proper hand hygiene).

The pathophysiology of congenital toxoplasmosis is complex, involving direct parasitic invasion, host inflammatory responses, and disruption of fetal development.

Once in the fetal circulation, tachyzoites disseminate throughout the body and can infect virtually any nucleated cell. The primary mechanisms of damage include:

- Direct Cellular Lysis: Tachyzoites rapidly multiply within host cells, forming vacuoles. As they multiply, they eventually cause the host cell to rupture, releasing more tachyzoites to infect neighboring cells. This direct destruction of cells contributes significantly to tissue damage.

- Host Inflammatory Response: The presence of the parasite triggers a robust fetal immune and inflammatory response. While intended to clear the infection, this inflammation can also cause significant collateral damage to delicate developing fetal tissues. This immune response involves cytokines and immune cells that can contribute to tissue destruction and fibrosis.

- Cyst Formation: As the fetal immune system attempts to control the acute infection, tachyzoites differentiate into bradyzoites, which form dormant tissue cysts within cells. These cysts can persist for the lifetime of the host, primarily in the brain, eyes, and muscles. While dormant, they can reactivate later in life (e.g., due to immunosuppression), leading to recurrent disease, particularly in the eyes.

- Disruption of Organogenesis: If infection occurs early in pregnancy (first trimester), when vital organs are undergoing rapid formation and differentiation, the cellular destruction and inflammation can severely disrupt normal organogenesis, leading to severe malformations or even fetal demise.

The tropism of Toxoplasma gondii for neural and retinal tissue, combined with the vulnerability of the developing fetus, leads to characteristic patterns of damage:

- Hydrocephalus: Caused by obstruction of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) flow, often due to ependymitis (inflammation of the lining of the brain ventricles) or aqueductal stenosis, resulting from inflammation and scarring.

- Intracranial Calcifications: These are characteristic findings, often scattered throughout the brain parenchyma, particularly periventricularly. They represent areas of necrosis and inflammation that have healed with calcification.

- Microcephaly: May occur due to extensive brain destruction.

- Developmental Delay/Intellectual Disability: Resulting from direct neuronal damage, inflammation, and altered brain development.

- Seizures: Due to brain lesions and scarring.

- Chorioretinitis: This is the hallmark ocular lesion. It involves inflammation and scarring of the choroid (vascular layer) and retina. Lesions can be active (inflamed) or inactive (scarred) at birth. Active lesions can cause pain and vision loss. Inactive scars can reactivate later in life, leading to recurrent inflammation and progressive vision loss.

- Microphthalmia: Abnormally small eyes.

- Strabismus (crossed eyes): Due to visual impairment.

- Nystagmus (involuntary eye movements): Due to visual impairment.

- Blindness: Can result from severe, bilateral chorioretinitis or optic nerve involvement.

- Liver and Spleen: Hepatosplenomegaly (enlarged liver and spleen) is common due to generalized infection and inflammation.

- Lymphatic System: Lymphadenopathy (enlarged lymph nodes) can occur.

- Hematological: Anemia and thrombocytopenia (low platelet count) can be present.

- Skin: Petechiae, purpura, or rash (generalized macular papular rash) may be seen.

- Lungs: Pneumonitis (inflammation of the lungs).

- Heart: Myocarditis (inflammation of the heart muscle) can occur but is less common.

Only a minority (10-20%) of congenitally infected infants show overt signs of disease at birth. These infants typically experienced maternal infection earlier in pregnancy.

This severe form is characterized by the combination of:

- Chorioretinitis: Inflammation and scarring of the retina and choroid, often leading to vision impairment. This can be active (inflamed) or inactive (scarred) at birth.

- Hydrocephalus: Abnormal accumulation of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) within the brain, leading to an enlarged head circumference (macrocephaly), increased intracranial pressure, and potential brain damage.

- Intracranial Calcifications: Characteristic deposits of calcium within the brain tissue, often scattered and periventricular, indicative of previous tissue destruction and healing.

- Prematurity: Higher incidence in infected infants.

- Intrauterine Growth Restriction (IUGR): Small for gestational age.

- Hepatosplenomegaly: Enlargement of the liver and spleen, due to generalized infection.

- Jaundice: Yellow discoloration of the skin and eyes, indicating liver dysfunction or hemolysis.

- Fever: Although less common at birth, can be present.

- Seizures: Due to brain lesions and inflammation.

- Microcephaly: Abnormally small head, in contrast to hydrocephalus which causes macrocephaly. This indicates significant brain tissue destruction.

- Poor feeding, lethargy, hypotonia (poor muscle tone).

- Microphthalmia: Abnormally small eyes.

- Strabismus, Nystagmus: Often secondary to vision impairment from chorioretinitis.

- Anemia: Low red blood cell count.

- Thrombocytopenia: Low platelet count, potentially leading to petechiae (small red spots) or purpura (larger purple patches) due to bleeding under the skin.

- Rash: Non-specific macular, papular, or petechial rash.

This is where the majority of issues arise, particularly in infants who were asymptomatic at birth. These sequelae can appear weeks, months, or even years after birth, highlighting the importance of long-term follow-up.

- Recurrent Chorioretinitis: The most frequent and significant long-term complication. Dormant tissue cysts in the retina can reactivate, causing new inflammatory lesions or exacerbating existing scars. This leads to progressive vision loss, pain, photophobia (light sensitivity), and floaters. It can occur at any age, often into adolescence and adulthood.

- Strabismus, Nystagmus, Amblyopia ("lazy eye"): Resulting from long-standing vision impairment.

- Glaucoma, Cataracts: Less common, but can develop.

- Blindness: Can be a devastating outcome of severe or recurrent chorioretinitis.

- Developmental Delays: Ranging from mild learning disabilities to severe intellectual disability, motor delays, and speech delays.

- Seizures: Can emerge or persist despite initial treatment.

- Hearing Loss: Sensorineural hearing loss can occur.

- Spasticity: Increased muscle tone and stiffness.

- Visual Impairment/Cortical Blindness: Even without direct eye damage, brain damage can impair visual processing.

- Precocious Puberty: Early onset of puberty in girls, potentially related to hypothalamic damage.

- Learning Disabilities and Behavioral Problems: Even with subtle brain involvement.

The primary method for diagnosing maternal Toxoplasma infection is serological testing. The interpretation of these tests is crucial as it determines whether a woman has a past infection (immune), is currently acutely infected, or is susceptible.

- Presence (positive): Indicates past or current infection. A rising IgG titer over several weeks (paired sera) suggests a recent infection.

- Absence (negative): Indicates susceptibility to infection.

- Presence (positive): Often indicates a recent or acute infection. However, IgM can persist for months to over a year after acute infection, so a positive IgM alone is not definitive for acute infection during pregnancy. It warrants further investigation.

- Absence (negative): Rules out recent infection in most cases, especially if accompanied by negative IgG.

- Similar to IgM, IgA antibodies usually appear shortly after infection and decline within a few months. They can aid in diagnosing recent infection, particularly when IgM results are equivocal.

- Low IgG Avidity: Suggests a recent infection (typically within the last 3-4 months). This is because in the early stages of infection, IgG antibodies bind weakly to the parasite antigen.

- High IgG Avidity: Suggests an infection acquired more than 3-4 months ago (i.e., remote infection). In later stages, IgG antibodies bind more strongly.

- Clinical Utility: A high IgG avidity in the first trimester of pregnancy usually rules out an infection acquired during the current pregnancy, thus reducing anxiety and potentially avoiding unnecessary interventions.

- IgG negative, IgM negative: Susceptible. Counsel on prevention. Re-test if symptoms develop or exposure occurs.

- IgG positive, IgM negative (High Avidity): Past infection, immune. No risk to fetus.

- IgG positive, IgM positive (Low Avidity): Recent infection (likely during pregnancy). High risk for fetal transmission. Further fetal diagnostic testing is indicated.

- IgG positive, IgM positive (High Avidity): Infection likely occurred several months ago (before or early in pregnancy). Lower risk for current pregnancy, but further evaluation may be considered.

- IgG negative, IgM positive: Possible very early acute infection, or false positive IgM. Repeat testing, consider confirmatory tests.

If maternal serology suggests a primary infection during pregnancy, fetal diagnostic procedures are offered to confirm (or rule out) fetal infection.

- Timing: Typically performed after 18 weeks of gestation and at least 4 weeks after the estimated time of maternal infection to allow for parasite multiplication in fetal fluids.

- Procedure: Fetal amniotic fluid is collected.

- Analysis:

- PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction): This is the most sensitive and specific method for detecting Toxoplasma gondii DNA in amniotic fluid. A positive PCR confirms fetal infection.

- Fetal Serology: Less reliable as the fetal immune response might not be robust enough to produce antibodies at this stage.

- Purpose: To look for sonographic signs of fetal infection and damage.

- Findings: Hydrocephalus, microcephaly, intracranial calcifications, hepatosplenomegaly, ascites (fluid in abdomen), fetal growth restriction, abnormal cardiac findings.

- Limitations: Ultrasound findings may be absent even in infected fetuses, especially early in infection or with milder forms. Its main role is to assess the severity of damage if infection is present.

- Purpose: To test fetal blood directly.

- Analysis: Fetal IgM, IgA, or PCR for Toxoplasma.

- Limitations: Invasive, higher risk than amniocentesis, and often replaced by amniotic fluid PCR due to its accuracy.

Diagnosis in the neonate confirms that the baby is infected and guides treatment.

- Neonatal Serology:

- IgM and IgA: A positive specific IgM or IgA in the newborn's blood definitively indicates congenital infection, as maternal IgM/IgA do not cross the placenta.

- IgG: All infants born to IgG-positive mothers will have maternal IgG antibodies. Therefore, the presence of IgG alone is not diagnostic of congenital infection. Serial IgG titers are used:

- Persistently positive or rising IgG titers beyond 12 months of age: Indicates active congenital infection.

- Declining IgG titers that become negative by 12 months: Indicates passive transfer of maternal antibodies, and the infant is not infected.

- PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction): Detection of Toxoplasma gondii DNA in neonatal blood, CSF, or urine. Highly sensitive and specific.

- Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) Examination: Analysis includes elevated protein, pleocytosis (increased cell count), and sometimes Toxoplasma DNA by PCR. Essential for assessing CNS involvement.

- Ophthalmological Examination: Findings are mandatory for all suspected cases. Dilated funduscopic examination can reveal active chorioretinitis or healed scars, even in asymptomatic infants.

- Neuroimaging:

- Cranial Ultrasound (for open fontanelle): Can detect hydrocephalus, ventriculomegaly, and intracranial calcifications.

- CT Scan or MRI of the Brain: Provides more detailed imaging of brain pathology, including calcifications, hydrocephalus, and other lesions.

- Other Investigations:

- Complete Blood Count (CBC): To check for anemia, thrombocytopenia.

- Liver Function Tests: To check for jaundice and hepatosplenomegaly.

The medical management of congenital toxoplasmosis involves specific drug regimens for pregnant women, neonates, and infants, with the goals of reducing vertical transmission, preventing or minimizing disease severity, and managing complications.

The goal is to prevent or reduce the risk of transmission to the fetus and to mitigate fetal damage if transmission has already occurred. The choice of medication depends on whether fetal infection has been confirmed.

- Drug: Spiramycin

- Mechanism: Spiramycin is a macrolide antibiotic that concentrates in the placenta. It is thought to reduce the rate of vertical transmission from mother to fetus, but it does not treat the fetus once infected.

- Regimen: Typically given as 1 g orally three times daily throughout the remainder of the pregnancy, or until fetal infection is confirmed.

- Side Effects: Generally well-tolerated, with mild gastrointestinal upset being most common.

- Pyrimethamine: A dihydrofolate reductase inhibitor, blocking folic acid synthesis in the parasite. It can cross the placenta. Pyrimethamine when given in high doses may cause haemolytic anaemia therefore monitor closely. Dose: 50-75mg OD PO for 2-3weeks then 25-37.5mg OD PO for 4-5 weeks

- Sulfadiazine: A sulfonamide antibiotic that inhibits dihydropteroate synthase, another enzyme in the parasite's folic acid pathway. It also crosses the placenta. Dose: 1-1.5g QID for 3-4 weeks or 100mg/kg/day in 2DD

- Leucovorin (Folnic Acid): Given to the mother (and later to the infant) to counteract the bone marrow suppressive effects (myelosuppression) of pyrimethamine, which can lead to thrombocytopenia and neutropenia by interfering with human folate metabolism. It is crucial to give leucovorin whenever pyrimethamine is used.

All infants with confirmed congenital toxoplasmosis (symptomatic or asymptomatic) should receive prolonged anti-parasitic treatment to prevent or minimize the development of long-term sequelae, particularly ocular and neurological damage.

- Pyrimethamine: Given daily or three times a week.

- Sulfadiazine: Given twice daily.

- Leucovorin: Given daily to mitigate pyrimethamine's side effects.

- Active chorioretinitis: Especially if threatening the macula or optic nerve.

- Significant inflammation in the CNS: Such as severe hydrocephalus with high protein in CSF.

Due to the potential side effects of the medications, especially pyrimethamine and sulfadiazine, close monitoring is essential.

- Hematological Monitoring: Regular (e.g., weekly or bi-weekly) complete blood counts (CBC) with differential and platelet counts to detect myelosuppression (anemia, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia). Doses may need adjustment or temporary interruption if severe myelosuppression occurs.

- Renal Function: Monitoring of BUN and creatinine, especially with sulfadiazine, to prevent crystalluria.

- Liver Function: Monitoring of liver enzymes.

- Clinical Monitoring: Regular assessment for drug rashes, gastrointestinal upset, and signs of disease progression.

- Hydrocephalus: May require neurosurgical intervention, such as placement of a ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunt to drain excess CSF and relieve intracranial pressure.

- Chorioretinitis: In addition to anti-parasitic treatment and corticosteroids, ophthalmological follow-up is critical. Regular eye exams are needed to monitor for active lesions, assess visual acuity, and manage complications.

- Developmental Delays: Referrals for early intervention programs including physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy, and special education services are crucial to optimize developmental outcomes.

Even after completing the initial 12 months of treatment, long-term follow-up is essential, often extending into adolescence and adulthood, due to the risk of delayed sequelae (especially recurrent chorioretinitis).

- Regular ophthalmological examinations.

- Neurological assessments.

- Developmental evaluations.

Prevention is paramount in congenital toxoplasmosis, as timely identification and avoidance of exposure in susceptible pregnant women can entirely avert fetal infection and its associated morbidities.

These recommendations focus on reducing exposure to Toxoplasma gondii from food and environmental sources. Education of pregnant women (and women of childbearing age) is key.

- Cook Meat Thoroughly: Ensure all meat, especially pork, lamb, and venison, is cooked to safe internal temperatures (e.g., 160°F/71°C for ground meat, 145°F/63°C for whole cuts with a 3-minute rest time) until no pink remains and juices run clear. Freezing meat to -4°F (-20°C) for several days can also kill tissue cysts.

- Wash Fruits and Vegetables: Thoroughly wash all raw fruits and vegetables before consumption, especially those grown in gardens where cats might roam.

- Avoid Raw/Undercooked Meat: Refrain from eating raw or undercooked meat, including cured meats unless they have been previously frozen.

- Prevent Cross-Contamination: Use separate cutting boards and utensils for raw meat and produce. Wash hands, cutting boards, and all utensils thoroughly with hot, soapy water after contact with raw meat.

- Avoid Cleaning: Ideally, pregnant women should avoid changing cat litter boxes. If unavoidable, wear gloves and wash hands thoroughly afterwards.

- Daily Cleaning: Have someone else clean the litter box daily, as Toxoplasma oocysts do not become infective until 1-5 days after being shed in feces.

- Dispose Safely: Dispose of cat feces carefully, ideally by flushing or bagging and placing in sealed waste.

- Wear Gloves: Wear gloves when gardening or handling soil, sand, or anything that might be contaminated with cat feces.

- Wash Hands: Wash hands thoroughly with soap and water after outdoor activities.

- Keep Cats Indoors: This prevents them from hunting and eating infected rodents or birds, which are sources of Toxoplasma.

- Avoid Feeding Raw Meat: Do not feed raw or undercooked meat to cats.

- No New Cats During Pregnancy: Avoid acquiring new cats during pregnancy, especially stray or feral cats, unless they have been tested for Toxoplasma.

- Universal Screening: Some countries (e.g., France, Austria) implement universal serological screening for Toxoplasma at the beginning of pregnancy (first trimester).

- Targeted Screening: In other regions (e.g., USA), screening is often targeted only to women who develop symptoms suggestive of infection or have known exposure.

- Benefits of Screening: Early detection of maternal seroconversion allows for prompt initiation of spiramycin, which can significantly reduce the risk of vertical transmission.

- Animal Control: Efforts to control feral cat populations in certain areas.

- Water Treatment: Ensuring safe drinking water to prevent oocyst ingestion.

- Public Education Campaigns: Raising awareness about Toxoplasma and its prevention methods among the general population, especially women of childbearing age.

- Risk for Infection, related to compromised immune system and presence of parasitic infection.

- Inadequate protein energy nutritional intake, related to increased metabolic demands, poor feeding, or gastrointestinal disturbances (e.g., jaundice, hepatosplenomegaly).

- Risk for Delayed Development, related to neurological damage, visual impairment, or hearing deficits.

- Impaired Physical Mobility, related to neurological damage (e.g., hydrocephalus, spasticity) and developmental delays.

- Acute Pain, related to inflammation (e.g., active chorioretinitis, CNS inflammation) or surgical interventions (e.g., shunt placement).

- Compromised Family Coping, related to chronic illness, uncertain prognosis, and demands of prolonged treatment and care.

- Inadequate health Knowledge (Parents), related to disease process, treatment regimen, potential complications, and long-term care needs.

- Risk for Caregiver Role Strain, related to complexity of care, financial burden, emotional stress, and lack of support systems.

- Excessive Anxiety (Parents), related to diagnosis, prognosis, potential for sequelae, and future care needs.

| Intervention Category | Action & Rationale |

|---|---|

| 1. Infection Control & Medication Management |

|

| 2. Nutritional Support |

|

| 3. Developmental and Sensory Support |

|

| 4. Pain Management |

|

| 5. Psychosocial & Educational Support |

|

| 6. Long-Term Follow-up Coordination |

|

Pathophysiology of congenital toxoplasmosis

good notes pliz

Best research site for nurses to improve on professional skills and knowledge

Thanx alot for that research continue with the same spirit

Thanks for the research

Thnx for the notes,,

I like it

Very nice notes thank you

I love this site…makes my revision simplified