Table of Contents

ToggleIntroduction to Immunity

Pathogens are foreign disease-causing substances, such as bacteria and viruses, and people are exposed to them every day.

Antigens are attached to the surface of pathogens and stimulate an immune response in the body.

An immune response is the body’s defense system to fight against antigens and protect the body.

Immunity is the body's ability to resist infection and disease. It is a state of having sufficient biological defenses to avoid invasion by pathogens and to destroy foreign substances.

Immunology is the scientific study of this complex system and how it responds to challenges.

Terminology in Immunology

- Pathogen: A foreign, disease-causing microorganism, such as a bacterium, virus, fungus, or parasite.

- Antigen (Ag): Any substance, usually a protein or polysaccharide on the surface of a pathogen, that is recognized as "foreign" by the immune system and provokes an immune response. Think of antigens as the "uniforms" that identify an invader.

- Antibody (Ab) or Immunoglobulin (Ig): A highly specific protein produced by plasma cells (a type of B-lymphocyte) in response to a specific antigen. Antibodies bind to antigens to neutralize them or mark them for destruction.

- Immunogen: Any antigen that is capable of inducing a humoral (antibody) and/or cell-mediated immune response. All immunogens are antigens, but not all antigens are immunogens (some are too small or simple to provoke a response on their own).

- Hapten: A small molecule that can only provoke an immune response when it is attached to a larger carrier protein. On its own, it is an antigen but not an immunogen.

- Chemotaxis: The chemical attraction of phagocytic cells (like neutrophils and macrophages) to a site of injury or infection. They follow a chemical trail of substances called chemokines.

- Chemokines: A family of small proteins that act as chemical messengers, stimulating the movement of leukocytes (white blood cells) towards the source of inflammation.

Types of immunity

The immune system is broadly divided into two interconnected branches:

- Innate (Non-specific) Immunity: The body's general, inborn protection against all invaders. It acts immediately or within hours and does not have immunological memory. It includes physical barriers and general immune cells.

- Adaptive (Acquired/Specific) Immunity: A highly specific defense system that is "acquired" during life after exposure to a pathogen or vaccine. It is characterized by specificity for a particular pathogen and immunological memory, allowing for a much stronger response upon re-exposure.

1. Innate Immunity: The First and Second Lines of Defense

Innate immunity is our built-in defense system. It is non-specific, meaning it responds in the same way to all pathogens, and it does not "remember" previous encounters.

Types of innate immunity

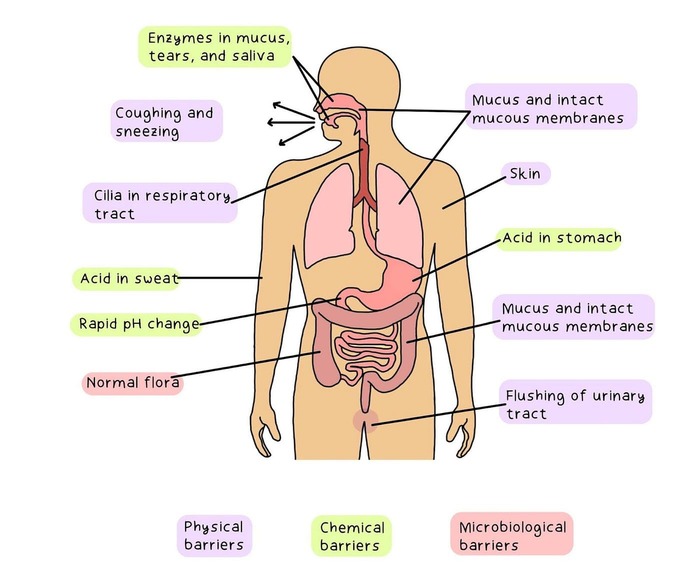

- First line of defenses These barriers are designed to prevent pathogens from entering the body in the first place.

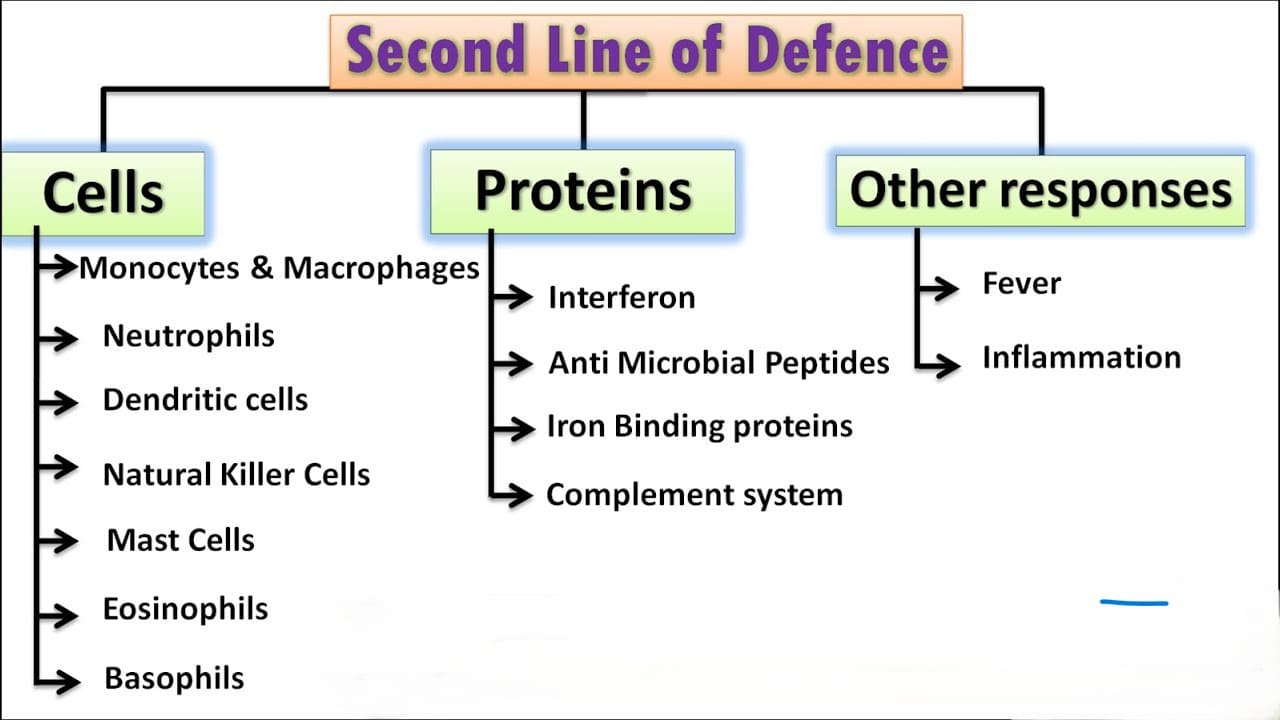

- Second line of defenses If pathogens breach the first line of defense, they encounter a range of non-specific internal defenses.

First Line of Defense: External or Physical and Chemical Barriers

These barriers are designed to prevent pathogens from entering the body in the first place.

- Ciliary Escalator: The ciliated epithelium of the upper respiratory tract constantly sweeps mucus (with trapped dust and pathogens) up towards the pharynx, where it is swallowed and destroyed in the stomach.

- Tears (Lacrimal Apparatus): Constantly wash the surface of the eye to dilute and remove microbes.

- Saliva: Washes microbes from the teeth and mouth.

- Urine Flow: The one-way flow of urine through the urethra mechanically flushes out microbes, preventing ascending infections.

- Vaginal Secretions: Move microbes out of the female reproductive tract.

Blinking spreads tears over the surface of the eyeball, and the continual washing action of tears helps to dilute microbes and keep them from settling on the surface of the eye. Tears also contain lysozyme, an enzyme capable of breaking down the cell walls of certain bacteria.

- Acidity: The low pH of skin (3-5), gastric juice (1.2-3.0), and vaginal secretions discourages the growth of most microbes.

- Lysozyme: An enzyme found in tears, saliva, nasal secretions, and perspiration that can break down the peptidoglycan cell walls of bacteria.

Second Line of Defense: Internal Defenses

When pathogens penetrate the physical and chemical barriers of the skin and mucous membranes, they encounter a second line of defense which include the following:

1. Internal Antimicrobial Substances

- Causing lysis (bursting) of microbial cells.

- Stimulating inflammation.

- Enhancing phagocytosis by coating pathogens (a process called opsonization).

2. Defensive Cells

- Neutrophils: The most abundant type of white blood cell. They are the "first responders" that rapidly move to sites of infection to perform phagocytosis.

- Macrophages ("Big Eaters"): Develop from monocytes. Fixed macrophages reside in specific tissues (e.g., in the liver, lungs), while wandering macrophages roam through tissues. They are powerful phagocytes and also act as Antigen-Presenting Cells (APCs).

- Dendritic Cells: Also phagocytes and potent APCs, found in skin and mucous membranes.

3. Inflammation: The Body's Emergency Response

Inflammation is the physiological response to tissue damage. Its purpose is protective: to isolate the problem, inactivate and remove the causative agent and damaged tissue, and initiate repair.

The Cardinal Signs of Inflammation:

- Redness (Rubor): Caused by vasodilation (widening) of arterioles and capillaries in the damaged area, which increases blood flow. This is triggered by chemical mediators like histamine.

- Heat (Calor): Results from the increased blood flow. The localized increase in temperature can inhibit microbial growth and enhance the activity of immune cells.

- Swelling (Tumor): Caused by increased capillary permeability. Fluid (exudate) and plasma proteins leak from the blood into the interstitial spaces, leading to edema.

- Pain (Dolor): Results from the compression of sensory nerve endings by the swelling and from irritation by chemical mediators like bradykinin and prostaglandins.

- Loss of Function (Functio Laesa): The combination of swelling and pain may temporarily limit movement of the affected area, which helps protect it from further injury.

4. Immulogical surveillance

- Natural killer (NK cells) cells: are leukocytes that attack and destroy tumor cells, or cells that have been infected by viruses

Although they are lymphocytes, they are much less selective about their targets than the other T-cells & B-cells.

2. Adaptive Immunity: The Specific and Memory-Based Defense

Adaptive immunity is a highly specific, powerful defense system that develops throughout our lifetime. It is "acquired" after exposure to a pathogen or vaccine. Its two defining characteristics are specificity (it targets one particular antigen) and memory (it "remembers" past encounters, leading to a much faster and stronger response upon re-exposure).

Lymphocytes

The Cells of Adaptive Immunity

B-lymphocytes (B-cells) and T-lymphocytes (T-cells) are the major players. Both originate from stem cells in the bone marrow but mature in different locations.

T-Cells and Cell-Mediated Immunity

T-cells are responsible for cell-mediated immunity, which is crucial for fighting intracellular pathogens (like viruses and some bacteria) and eliminating abnormal body cells (like cancer cells). They mature in the Thymus gland.

- Helper T-Cells (TH or CD4+ cells): The "generals" of the immune system. When activated, they produce chemical messengers called cytokines that coordinate the entire immune response. They help activate cytotoxic T-cells, B-cells, and macrophages. HIV specifically targets and destroys these cells, crippling the immune system.

- Cytotoxic T-Cells (TC or CD8+ cells): The "soldiers." They directly track down and kill any body cells displaying the specific antigen they recognize (e.g., virus-infected cells, tumor cells) by releasing powerful toxins.

- Suppressor (Regulatory) T-Cells (Treg): These cells turn off the immune response after the pathogen has been cleared, preventing excessive and potentially damaging immune activity.

- Memory T-Cells: Long-lived cells that persist after the infection is resolved, ready to mount a swift response upon re-exposure to the same antigen.

B-Cells and Humoral (Antibody-Mediated) Immunity

B-cells are responsible for humoral immunity, which involves the production of antibodies that circulate in the body's fluids ("humors" like blood and lymph). This is most effective against extracellular pathogens like bacteria circulating in the blood. B-cells are produced and mature in the Bone marrow.

- Plasma Cells: These are "antibody factories." They dedicate all their energy to producing and secreting thousands of antibody molecules per second into the bloodstream. These antibodies are specific to the antigen that initiated the response.

- Memory B-Cells: Long-lived cells that provide immunological memory, enabling a rapid and massive antibody production (the secondary response) if the same antigen is encountered again.

Types of Adaptive Immunity

Acquired (adaptive) immunity develops during an individual's lifetime. It can be classified into two major categories—Active and Passive—each of which can be acquired either naturally or artificially.

Active Immunity: The Body's Own Production Line

Active immunity is protection that is induced in the host itself after exposure to an antigen. The individual's own immune system is stimulated to produce memory B-cells and T-cells. This process takes time to develop but results in long-lasting, sometimes lifelong, immunological memory.

1. Naturally Acquired Active Immunity

- Mechanism: This is the most natural way to become immune. It occurs when a person is exposed to a live pathogen through an infection (which may be a full-blown illness or a subclinical infection without symptoms).

- The Process: Upon first exposure, the body mounts a primary immune response. It manufactures specific antibodies and T-cells to fight the invading pathogen. While this initial response takes time (often allowing the person to get sick), it results in the creation of a large pool of memory cells.

- Outcome: For the rest of that individual's life, any subsequent exposure to the same pathogen will trigger a rapid and powerful secondary immune response. The memory cells will mobilize to produce antibodies and T-cells so quickly that the invading antigen is destroyed before it can cause disease.

- Clinical Example: A child who gets sick with and recovers from chickenpox develops naturally acquired active immunity. They are protected from getting chickenpox again for the rest of their life.

2. Artificially Acquired Active Immunity

- Mechanism: This type of immunity is acquired through the deliberate action of vaccination (immunization). An individual is intentionally given a prepared antigen.

- The Process: The vaccine contains a safe form of the antigen—it might be a killed pathogen, a live attenuated (weakened) pathogen, a subunit (a piece of the pathogen), or a toxoid (an inactivated toxin). This antigen is enough to stimulate the recipient's immune system to produce its own antibodies and memory cells, but it does not cause the actual disease.

- Outcome: The individual develops long-term immunity without ever having to suffer through the illness. Sometimes, a person might experience minor symptoms like a low-grade fever or soreness after a vaccine; this is a sign that their immune system is actively learning to fight the antigen.

- Clinical Example: A baby receiving the Measles, Mumps, and Rubella (MMR) vaccine. The vaccine contains live attenuated viruses, which stimulate the baby's immune system to create memory cells against all three diseases, providing long-term protection.

Passive Immunity: Borrowed Protection

Passive immunity is protection that is acquired through the transfer of pre-formed antibodies from an immune individual to a non-immune individual. The recipient's body does not produce the antibodies itself. This provides immediate protection but is always temporary because the "borrowed" antibodies are eventually broken down and eliminated, and no immunological memory is created.

1. Naturally Acquired Passive Immunity

- During Pregnancy: IgG antibodies are actively transported across the placenta from the mother's bloodstream to the fetus, especially during the last one to two months of pregnancy. A full-term infant is born with the same set of IgG antibodies as its mother.

- After Birth: IgA antibodies (secretory IgA) are transferred from the mother to the infant through breast milk (especially the colostrum). This IgA protects the baby's gastrointestinal tract from infections.

2. Artificially Acquired Passive Immunity

- It can be used prophylactically (to prevent disease) in individuals who have been exposed to an infection they are not immune to.

- It can be used therapeutically (to treat a disease) after symptoms have already developed, to help neutralize a toxin or pathogen.

- Giving Tetanus Immunoglobulin (TIG) to a person with a deep, contaminated wound who has an uncertain vaccination history.

- Giving Rabies Immunoglobulin (RIG) infiltrated around a wound from a suspected rabid animal bite.

- Giving pooled human immunoglobulin (IVIG) to treat immunodeficiency diseases like hypogammaglobulinemia.

Summary of Acquired Immunity

| Type of Immunity | How It Is Acquired | Memory Produced? | Duration | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naturally Acquired Active | Surviving an infection | Yes | Long-term / Lifelong | Recovering from measles |

| Artificially Acquired Active | Vaccination | Yes | Long-term / Lifelong | Receiving the polio vaccine |

| Naturally Acquired Passive | Antibodies from mother to child (placenta/breast milk) | No | Short-term (months) | An infant's temporary immunity to diseases the mother had |

| Artificially Acquired Passive | Injection of pre-formed antibodies (antiserum) | No | Short-term (weeks to months) | Receiving Rabies Immunoglobulin after a bite |

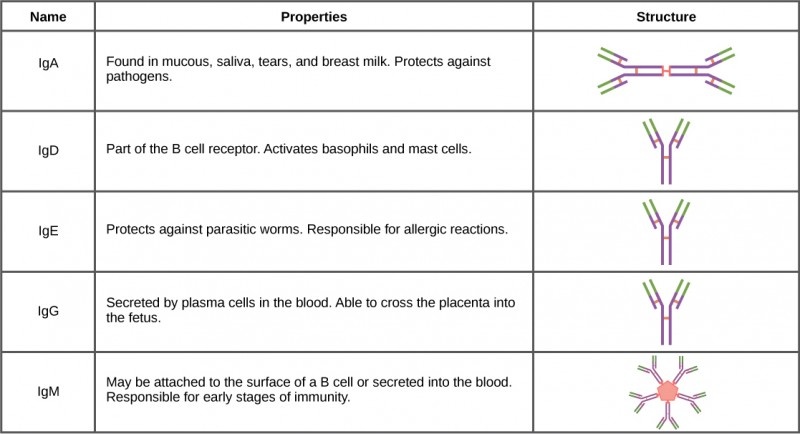

Antibodies (Immunoglobulins)

Antibodies are Y-shaped glycoprotein molecules produced by plasma cells in response to a specific antigen. They are found in blood serum and other body fluids. Their primary function is not to kill pathogens directly, but to bind to them and facilitate their destruction.

The Five Classes of Antibodies (Isotypes)

| Class | Abundance | Key Features and Functions |

|---|---|---|

| IgG (Gamma) | ~80% (Most abundant in serum) | Provides the majority of long-term antibody-based immunity. It is the only antibody class that can cross the placenta, providing passive immunity to the fetus. It is the main antibody in the secondary response. |

| IgA (Alpha) | ~15% | Known as the secretory antibody. Found in mucosal secretions (saliva, tears, mucus), respiratory, GI, and urogenital tracts. It prevents pathogens from colonizing and attaching to mucous membranes. Also found in breast milk, providing passive immunity to the infant's gut. |

| IgM (Mu) | ~10% | It is a very large molecule (a pentamer). It is the first antibody to be produced during a primary immune response, indicating a recent or current infection. It is a potent activator of the complement system. |

| IgD (Delta) | <1%< /td> | Functions mainly as an antigen receptor on the surface of B-cells. Its exact role is still being researched. |

| IgE (Epsilon) | ~0.002% (Lowest concentration) | Binds to mast cells and basophils. When it encounters its specific antigen (an allergen like pollen), it triggers the release of histamine, causing an allergic reaction. It also plays a role in defending against parasitic worm infections. |

Acquired Immunity

Acquired immunity develops during an individual's lifetime and can be classified based on how it was obtained: naturally or artificially, and actively or passively.

The Four Types of Acquired Immunity

-

Naturally Acquired Active Immunity:

- How it's acquired: By getting an infection. The body is exposed to a live pathogen, mounts a primary immune response, and develops long-lasting memory cells.

- Memory: Yes (long-term).

- Example: Recovering from chickenpox gives you lifelong immunity to that specific virus.

-

Naturally Acquired Passive Immunity:

- How it's acquired: Through the transfer of antibodies from mother to child. IgG crosses the placenta to the fetus, and IgA is passed through breast milk to the infant.

- Memory: No. The immunity is temporary (lasts a few months) because the infant did not make the antibodies themselves.

- Example: Protection of a newborn from infections during the first few months of life.

-

Artificially Acquired Active Immunity:

- How it's acquired: Through vaccination (immunization). The body is deliberately exposed to a harmless form of a pathogen (e.g., killed or weakened) or its antigens, which stimulates a primary immune response and creates memory cells without causing the disease.

- Memory: Yes (long-term).

- Example: The measles vaccine provides long-term protection against measles.

-

Artificially Acquired Passive Immunity:

- How it's acquired: Through the injection of pre-formed antibodies (immunoglobulins) from an immune human or animal. This provides immediate but temporary protection.

- Memory: No.

- Example: Giving someone an injection of tetanus antitoxin (antibodies against the tetanus toxin) after a deep, dirty wound for immediate protection while their own active immunity develops. Another example is giving Rabies Immunoglobulin (RIG) after a suspected rabid animal bite.

Hypersensitivity: When the Immune System Overreacts

The term hypersensitivity refers to an exaggerated or inappropriate immune response to an antigen that results in significant inflammation and damage to host tissues. While the immune system's job is to protect us, in hypersensitivity reactions, the protective response itself becomes the cause of the illness.

These reactions are classified into four types based on the primary immune mediators involved and the time it takes for a reaction to occur.

Type I: Immediate / Anaphylactic Hypersensitivity

- Sensitization Phase (First Exposure): An individual is exposed to an allergen (e.g., pollen, bee venom). Their B-cells are stimulated to produce large amounts of IgE antibodies against this allergen. This IgE then binds to the surface of mast cells and basophils, effectively "priming" them.

- Activation Phase (Subsequent Exposure): Upon re-exposure, the allergen binds to the IgE already attached to the mast cells. This triggers the immediate and massive release (degranulation) of inflammatory mediators like histamine, leukotrienes, and prostaglandins.

- Vasodilation and Increased Capillary Permeability: Leads to swelling (edema), skin rashes (hives/urticaria), and a dangerous drop in blood pressure.

- Bronchoconstriction: Contraction of smooth muscles in the airways, leading to wheezing and difficulty breathing (as seen in asthma).

- Increased Mucus Secretion: Causes a runny nose and watery eyes (as in hay fever).

- Systemic Anaphylaxis: A severe, life-threatening reaction to bee stings, food allergies (e.g., peanuts), or drugs (e.g., penicillin), causing circulatory collapse and airway obstruction.

- Atopic Diseases (Localized Allergies): Allergic asthma, hay fever (allergic rhinitis), eczema (atopic dermatitis), and hives (urticaria).

Type II: Antibody-Dependent Cytotoxic Hypersensitivity

- Complement Activation: The antibody-antigen complex on the cell surface activates the complement system, leading to the formation of the Membrane Attack Complex (MAC), which punches holes in the cell membrane, causing it to lyse (burst).

- Phagocytosis: The antibody acts as an opsonin, coating the cell and making it a prime target for phagocytes like macrophages.

- Antibody-Dependent Cell-Mediated Cytotoxicity (ADCC): Natural Killer (NK) cells bind to the antibodies attached to the host cell and release cytotoxic granules to kill it.

- Incompatible Blood Transfusion: If a person with Type B blood (with anti-A antibodies) receives Type A blood, their antibodies will attack the transfused red blood cells, causing massive hemolysis.

- Hemolytic Disease of the Newborn (Rh Incompatibility): An Rh-negative mother carrying an Rh-positive fetus can develop anti-Rh antibodies. In a subsequent Rh-positive pregnancy, these antibodies can cross the placenta and destroy the fetal red blood cells.

- Some Autoimmune Diseases: For example, in Goodpasture's syndrome, antibodies attack proteins in the kidneys and lungs.

Type III: Immune Complex-Mediated Hypersensitivity

These deposited complexes activate the complement system, which attracts a large number of neutrophils to the site. The frustrated neutrophils release their powerful lytic enzymes, causing inflammation and damage to the underlying tissue ("innocent bystander" damage).

- Serum Sickness: A classic example where a patient reacts to foreign proteins in injected antisera (e.g., from a horse). It causes fever, rash, joint pain, and kidney damage.

- Post-Streptococcal Glomerulonephritis: Kidney inflammation following a strep throat infection, caused by the deposition of streptococcal antigen-antibody complexes in the glomeruli.

- Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE): An autoimmune disease where complexes of self-antigens and autoantibodies deposit in multiple organs.

Type IV: Delayed-Type / Cell-Mediated Hypersensitivity

- Sensitization Phase: On first contact with the antigen (e.g., chemicals from poison ivy, proteins from M. tuberculosis), an Antigen-Presenting Cell (APC) presents it to Helper T-cells, creating a population of sensitized memory T-cells.

- Elicitation Phase: On second exposure, these memory T-cells are activated. They migrate to the site and release cytokines, which recruit and activate a large number of macrophages. It is the prolonged activity and cytokine release from these T-cells and macrophages that causes the inflammation and tissue damage.

- The Mantoux (Tuberculin) Skin Test: A classic example. If a person has been exposed to TB, their memory T-cells will cause a localized, hardened red swelling at the injection site 48-72 hours later.

- Contact Dermatitis: Skin rash caused by contact with substances like poison ivy, nickel in jewelry, or latex.

- Granuloma Formation: In chronic infections like tuberculosis and leprosy, the body forms granulomas to wall off the pathogen, which is a classic Type IV reaction causing tissue destruction over time.

Summary of Hypersensitivity Reactions

| Type | Name | Key Mediator | Onset Time | Mechanism Summary | Clinical Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type I | Immediate / Anaphylactic | IgE | Minutes | IgE on mast cells binds to allergen, triggering degranulation and histamine release. | Anaphylaxis, Asthma, Hay Fever, Hives |

| Type II | Cytotoxic | IgG, IgM, Complement | Hours to Days | Antibodies bind to antigens on host cells, leading to cell destruction. | Blood Transfusion Reactions, Hemolytic Disease of Newborn |

| Type III | Immune Complex | Antigen-Ab Complexes | Hours to Days | Soluble immune complexes deposit in tissues, causing inflammation and damage. | Serum Sickness, Post-Strep Glomerulonephritis, Lupus (SLE) |

| Type IV | Delayed-Type / Cell-Mediated | T-Cells & Macrophages | 24-72 Hours | Sensitized T-cells are activated, leading to cytokine release and macrophage-mediated inflammation. | TB Skin Test, Contact Dermatitis (Poison Ivy), Granuloma Formation |

Interesting and enjoyable for sure

Good questions