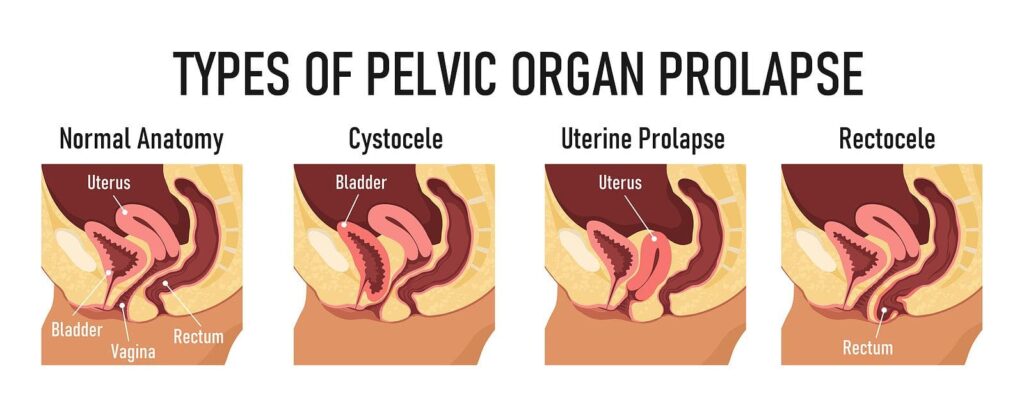

Pelvic Organ Prolapse (POP):

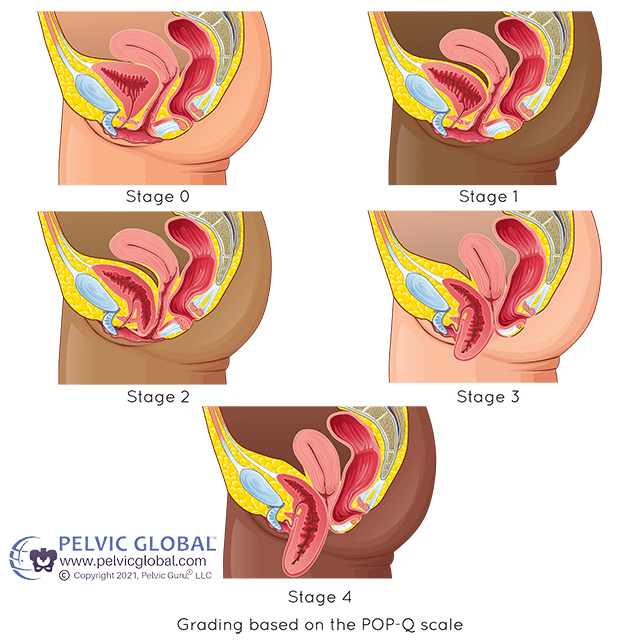

POP occurs when the muscles and ligaments that support the pelvic organs weaken, allowing these organs to bulge or drop into the vagina.

It is divided into three main categories:

1. Anterior Vaginal Wall Prolapse:

Cystocele: This is the most common type of POP. It happens when the bladder bulges into the vagina. It can be graded from 1 to 3 based on the extent of the bulge:

- Grade 1: Mild, bladder only drops slightly into the vagina.

- Grade 2: Moderate, bladder drops further, reaching the vaginal opening.

- Grade 3: Severe, bladder bulges out through the vaginal opening.

Urethrocele: This occurs when the urethra, the tube that carries urine from the bladder, bulges into the vagina.

2. Apical Prolapse:

Enterocele: This is when a portion of the small intestine bulges into the upper part of the vagina.

Uterine Prolapse: This is a prolapse of the uterus itself into or out of the vagina. It is graded based on how far the cervix (the lower part of the uterus) has descended:

- Stage 0: No prolapse.

- Stage 1: Cervix descends less than 1 cm above the hymen.

- Stage 2: Cervix is at or within 1 cm of the hymen.

- Stage 3: Cervix descends more than 1 cm below the hymen.

- Stage 4: Complete uterine prolapse, the entire uterus is outside the vagina (procidentia).

Vaginal Vault Prolapse: This happens when the upper part of the vagina loses its support and sags or drops into the vaginal canal or outside the vagina.

3. Posterior Vaginal Wall Prolapse:

- Rectocele: This is a bulge of the rectum, the last part of the large intestine, into the back wall of the vagina.

- Rectal Prolapse: This is a different condition where part of the rectum turns inside out and protrudes through the anus. This is not a form of POP and is usually mistaken for hemorrhoids.

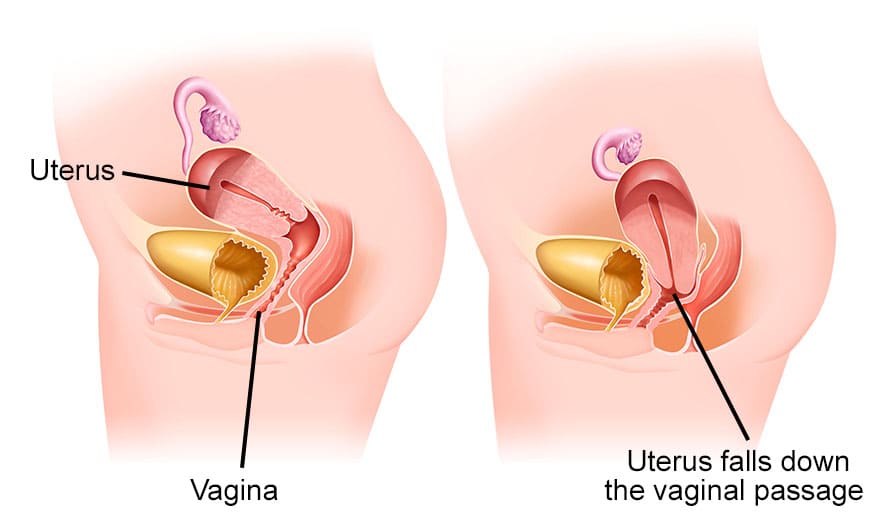

Prolapse of the Uterus

Uterine prolapse occurs when the uterus descends from its normal position into the vaginal canal due to weakened pelvic floor muscles and ligaments.

A uterine prolapse is a condition where the internal supports of the uterus become weak over time and the uterus sags out of position, descends downwards into the vagina.

Uterine prolapse (also called descensus or procidentia) means the uterus has descended from its normal position in the pelvis further down into the vagina.

Causes and Risk Factors of Uterine Prolapse

Uterine prolapse occurs when the pelvic floor muscles and ligaments, which normally support the uterus and other pelvic organs, become weakened or damaged. This allows the uterus to descend into or even protrude from the vagina.

Common causes include pregnancy, childbirth, hormonal changes after menopause, obesity, severe coughing and straining on the toilet.

1. Pregnancy and Childbirth:

- Vaginal Delivery: The strain of pushing during labor, especially with large babies, can weaken the pelvic floor muscles.

- Multiple Pregnancies: Repeated pregnancies can further stretch and weaken these muscles.

2. Age and Menopause:

- Advanced Age: As we age, our tissues naturally lose elasticity and strength, including the pelvic floor.

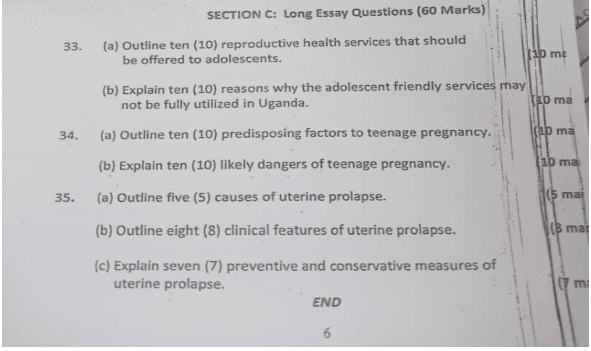

- Menopause: The decline in estrogen levels during menopause can contribute to tissue thinning and weakening.

3. Other Factors:

- Chronic Cough: Conditions like bronchitis, asthma, or even persistent coughing can put strain on the pelvic floor.

- Constipation: Straining during bowel movements can weaken the pelvic floor.

- Major Pelvic Surgery: Procedures like hysterectomy or pelvic tumor removal can damage the supporting structures.

- Smoking: Smoking reduces estrogen levels and can negatively impact tissue elasticity.

- Excess Weight Lifting: Heavy lifting can strain the pelvic floor muscles.

- Obesity: Excess weight puts added pressure on the pelvic floor.

- Pelvic Tumors: While rare, pelvic tumors can displace the uterus and contribute to prolapse.

- Spinal Cord Injuries: Conditions like muscular dystrophy, multiple sclerosis, or spinal cord injuries can weaken the pelvic floor muscles.

- Family History: A family history of uterine prolapse increases the risk.

Pathophysiology:

The pelvic floor muscles and ligaments act as a hammock, supporting the uterus, bladder, and rectum. When these structures are weakened, the uterus can descend into the vagina.

Staging of Uterine Prolapse

Uterine prolapse is staged based on how far the cervix has descended:

- First Degree: The cervix drops into the vagina.

- Second Degree: The cervix descends to the level just inside the opening of the vagina.

- Third Degree: The cervix protrudes outside the vagina.

- Fourth Degree: The entire uterus is outside the vagina.

Clinical Features:

Symptoms of uterine prolapse vary depending on the severity but can include:

- Feeling of fullness or pressure in the pelvis

- Low back pain

- Sensation of something coming out of the vagina

- Bulging in the vagina

- Painful sexual intercourse

- Discomfort walking

- Uterine tissue protruding from the vaginal opening

- Unusual or excessive vaginal discharge

- Constipation

- Recurrent UTIs

- Symptoms may worsen with prolonged standing or walking

- Urinary problems (incontinence, frequency)

- Difficulty with bowel movements

Diagnosis:

History taking: A detailed medical history about symptoms and risk factors.

Physical examination:

- Abdominal exam: To assess the size and position of the uterus.

- Pelvic exam: To examine the vagina and cervix.

- Bimanual exam: To assess the pelvic floor muscle strength and support.

Laboratory studies:

- CBC, urinalysis, and cervical cultures: May be performed if infection is suspected.

- Pap smear cytology or biopsy: To rule out cervical cancer.

- Pelvic ultrasound: To visualize the uterus and surrounding structures.

- MRI: May be used for staging and to assess the extent of prolapse.

Differential Diagnoses:

- Urinary Tract Infection (UTI) and Cystitis (Bladder Infection) in Females: Symptoms can be similar to prolapse.

- Early Pregnancy: A growing uterus can also cause pelvic pressure and a feeling of fullness.

- Neoplasm: Tumors in the pelvic area can also cause prolapse-like symptoms.

- Ovarian Cysts: Cysts on the ovaries can cause pressure and discomfort.

- Vaginitis: Vaginal inflammation can lead to discharge and discomfort.

Management of Uterine Prolapse

The management of uterine prolapse depends on the severity of the prolapse, the patient’s symptoms, and their overall health. It can range from conservative measures to surgical interventions.

Conservative Management:

- Exercise: Kegel exercises, which involve contracting and relaxing the pelvic floor muscles, can strengthen the supporting muscles and help alleviate symptoms.

- Estrogen Replacement Therapy (ERT): For postmenopausal women, ERT can improve tissue elasticity and strength, potentially preventing further weakening of pelvic floor structures.

- Pessary: A pessary is a removable device inserted into the vagina to support the uterus and hold it in place. It is a non-surgical option suitable for women who want to avoid surgery or are not candidates for it. Pessaries come in various shapes and sizes, and they need to be fitted from the facility.

- Lifestyle modifications:

- Weight Management: Maintaining a healthy weight reduces strain on the pelvic floor.

- Dietary changes: Consuming a high-fiber diet can help prevent constipation and minimize straining.

- Avoiding heavy lifting and prolonged standing: These activities can worsen prolapse symptoms.

Definitive Management (Surgery):

Surgery is considered when conservative options fail to provide relief or for severe prolapses.

- Vaginal Hysterectomy: This involves removing the uterus through the vagina. It is a common procedure for uterine prolapse, especially in women who are done having children.

- Abdominal Hysterectomy: This involves removing the uterus through an incision in the abdomen. It may be preferred in cases of severe prolapse or when there are other pelvic issues.

- Colpocleisis: This procedure involves surgically narrowing the vaginal opening, which provides support and eliminates the prolapse. It is considered for women who are not interested in sexual activity.

- Sacrospinous Fixation: This procedure involves attaching the uterus to the sacrospinous ligament, a strong ligament in the pelvis. This provides support to the uterus and prevents prolapse.

- Sacrohysteropexy: This procedure involves using a mesh patch to attach the uterus to the sacrum, a bone in the lower back. It is considered a more permanent solution than sacrospinous fixation.

Prevention of Uterine Prolapse:

- Maintaining a healthy weight: Obesity increases the risk of uterine prolapse.

- Regular exercise: Kegel exercises are especially helpful for strengthening the pelvic floor muscles.

- Healthy diet: High-fiber diet prevents constipation.

- Avoid straining: This includes straining during bowel movements and heavy lifting.

- Quit smoking: Smoking contributes to tissue weakening.

- Proper lifting techniques: Use your legs, not your back, to lift heavy objects.

- Minimizing vaginal deliveries: Multiple vaginal deliveries can weaken the pelvic floor.

Prolapse of the Cervix

Cervical prolapse is a type of pelvic organ prolapse where the cervix descends into the vaginal canal, often occurring along with uterine prolapse.

(Remember Cervix can not prolapse without the uterus too)

Causes:

- Similar to uterine prolapse (childbirth, aging, heavy lifting, chronic coughing)

Symptoms:

- Sensation of a bulge in the vagina

- Vaginal bleeding or discharge

- Difficulty with urination or bowel movements

Diagnosis:

- Pelvic examination

Treatment:

- Similar to uterine prolapse (pelvic floor exercises, pessary, surgery)

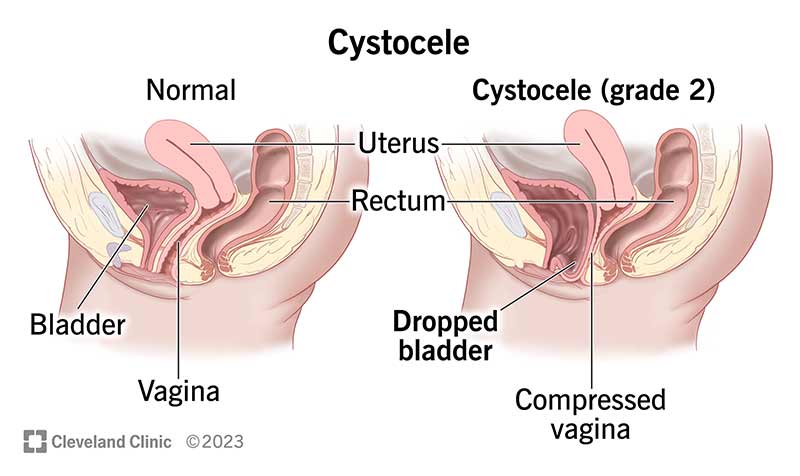

Prolapse of the Bladder (Cystocele)

Bladder prolapse, or cystocele, occurs when the bladder bulges into the vaginal wall due to weakened supportive tissues.

When both the bladder prolapse (cystocele) and urethra prolapse (urethrocele) occur together, its called Cystourethrocele.

Causes of Cystocele:

- Chronic constipation

- Heavy lifting

- Menopause and decreased estrogen levels

- Pregnancy and childbirth

- Aging / Menopause

- Hysterectomy

- Genetics

- Obesity

- Iatrogenic: Complicated operative deliveries and previous pelvic floor repair operations may be a contributory factor i.e. hysterectomy.

- Pelvic organ cancers e.g. cervical cancer e.t.c

Symptoms of Cystocele:

- Feeling of fullness or pressure in the pelvis

- Urinary incontinence or retention

- Frequent urinary tract infections

- Difficulty emptying the bladder

- A vaginal bulge

- The feeling that something is falling out of the vagina

- The sensation of pelvic heaviness or fullness

- Difficulty starting a urine stream and A feeling that you haven’t completely emptied your bladder after urinating plus Frequent or urgent urination

STAGES OF BLADDER PROLAPSE

Grade 1 (mild): Only a small portion of the bladder drops into the vagina.

Grade 2 (moderate): The bladder drops enough to be able to reach the opening of the vagina.

Grade 3 (severe): The bladder protrudes from the body through the vaginal opening.

Grade 4 (complete): The entire bladder protrudes completely outside the vagina

Diagnosis of Cystocele:

Initial Assessment:

- Pelvic Examination: This helps to examine the vagina and cervix to look for any bulging or prolapse. Assess the size and location of the prolapse to determine its severity.

- Abdominal Examination: This helps rule out any abdominal or pelvic masses that might be contributing to the prolapse by pushing down on the pelvic organs.

Further Diagnostic Tests:

- Urinalysis: A urine test can identify any urinary tract infections that could be contributing to bladder symptoms.

- Voiding Cystourethrogram (VCUG): This test involves filling the bladder with contrast dye and taking X-rays as the patient urinates. VCUG can help visualize the bladder and urethra, identifying any abnormalities like prolapse, narrowing, or leaks.

- Cystoscopy: This procedure involves inserting a thin, flexible scope with a camera into the urethra and bladder. It allows the doctor to visualize the inside of the bladder and urethra, looking for any structural problems or blockages.

Imaging Tests (May be used to confirm diagnosis and plan treatment):

- CT Scan of the Pelvis: This scan provides detailed images of the pelvic organs and surrounding structures, helping to underpin the extent of the prolapse.

- Ultrasound of the Pelvis: This non-invasive imaging technique uses sound waves to create pictures of the pelvic organs, aiding in the assessment of prolapse and potential causes.

- MRI Scan of the Pelvis: MRI provides very detailed images, allowing for a thorough examination of the pelvic floor muscles and ligaments.

Evaluating Associated Conditions:

- Stress Incontinence Test: To assess whether the cystocele is causing urinary leakage, the doctor may ask the patient to cough with a full bladder. This helps determine if the bladder leaks during increased pressure on the pelvic floor.

Treatment of a Cystocele:

Mild Cases (Grade 1): These often don’t require medical or surgical intervention. Lifestyle changes can help alleviate symptoms:

- Weight Loss: If overweight or obese, shedding extra pounds can reduce strain on the pelvic floor.

- Avoiding Heavy Lifting: Limit activities that put pressure on the pelvic floor.

- Treating Constipation: Regular bowel movements are important to avoid straining.

More Severe Cases (Grades 2-3): If symptoms significantly impact daily life, treatment options include:

- Pelvic Floor Exercises (Kegels): Strengthening these muscles can improve support for the pelvic organs.

- Hormone Treatment (Estrogen Replacement Therapy): This can improve tissue elasticity and support in some women.

- Vaginal Pessaries: These are removable devices that fit inside the vagina to support the prolapsed organs.

- Surgery: This is considered for significant prolapses or those not responding to other treatments. Surgical options include repairs of the pelvic floor muscles and ligaments, or in rare cases, Colpocleisis (a procedure that permanently reduces the size of the vagina).

Preventing a Cystocele:

- Regular Pelvic Floor Exercises: Strengthening these muscles daily can help prevent prolapse.

- Avoiding Heavy Lifting: Reduce strain on the pelvic floor by limiting activities that require heavy lifting.

- Maintain a Healthy Weight: Being overweight or obese puts extra stress on the pelvic floor.

- Regular Bowel Movements: Prevent constipation and straining by consuming enough fiber and staying hydrated.

- Moderate Exercise: Regular physical activity can help keep the pelvic floor muscles strong and improve overall health.

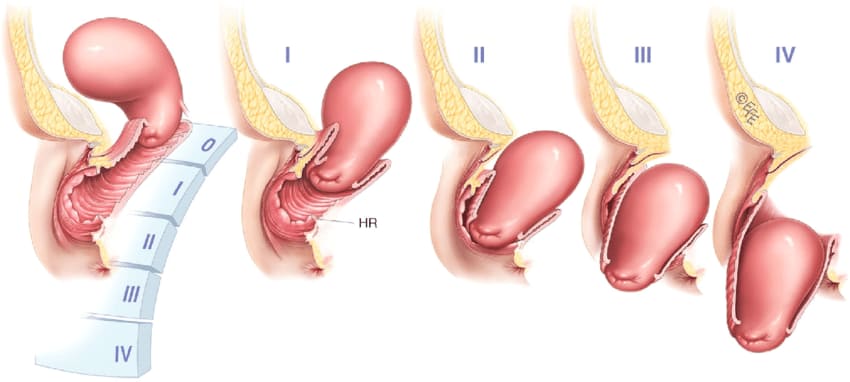

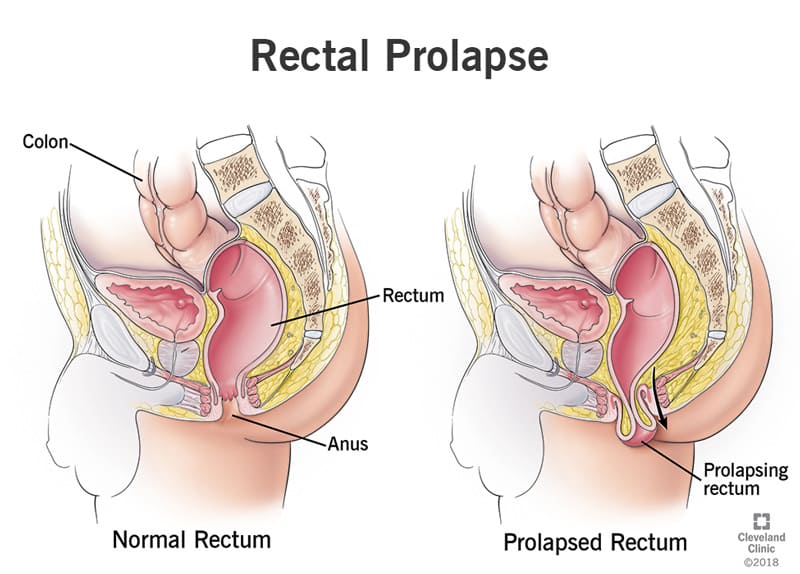

Rectal Prolapse

Rectal prolapse occurs when the rectum (the last section of the large intestine) falls from its normal position within the pelvic area and protrudes through the anus.

It can involve a mucosal or full-thickness layer of rectal tissue.

Epidemiology:

Rectal prolapse is more common in older adults with a long-term history of constipation or weakened pelvic floor muscles. It is more prevalent in women, especially those over 50 (postmenopausal women), but can also occur in younger individuals and infants.

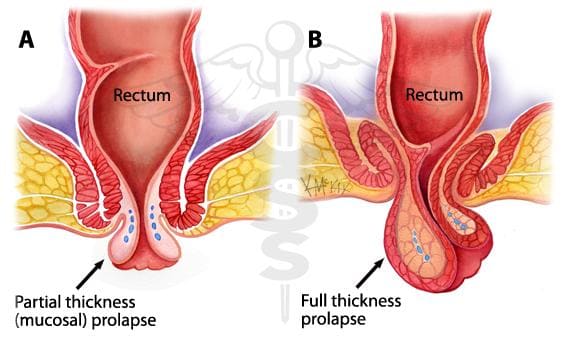

Types of Rectal Prolapse:

- External Prolapse (Full-thickness): The entire rectum sticks out of the anus.

- Mucosal Prolapse: Part of the rectal mucosal lining protrudes through the anus.

- Internal Prolapse (Intussusception): The rectum has started to drop but has not yet protruded through the anus. Internal Intussusception: Can be full-thickness or partial rectal wall disorder but does not pass beyond the anal canal.

Etiology and Risk Factors:

- Chronic straining with defecation and constipation

- Pregnancy/childbirth

- Previous surgery

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

- Cystic fibrosis

- Pertussis (whooping cough)

- Diarrhea

- Pelvic floor dysfunction

- Advanced age

- Neurological problems (e.g., spinal cord disease)

- Congenital bowel disorders (e.g., Hirschsprung’s disease)

- Earlier injury to the anal or pelvic muscles

- Damage to nerves controlling rectum and anus muscles

Pathophysiology:

Mucosal prolapse occurs when the connective tissue attachments of the rectal mucosa are loosened and stretched, allowing the tissue to prolapse through the anus.

Clinical Features:

- Mass protruding through the anus

- Variable pain

- Possible uterine or bladder prolapse (10-25% of cases)

- Constipation (15-65% of cases)

- Rectal bleeding

- Fecal incontinence (28-88%)

- Difficulty with defecation and sensation of incomplete evacuation

Diagnosis:

- History Taking and Physical Examination: Protruding rectal mucosa and thick concentric mucosal ring.

- Barium Enema and Colonoscopy: To view the rectum and colon.

- Proctography/Video Defecography: To document internal prolapse.

- Anal Electromyography (EMG): To determine nerve damage.

- Anal Ultrasound: To evaluate sphincter muscles.

- Pudendal Nerve Terminal Motor Latency Test: To measure function of pudendal nerves.

- Proctosigmoidoscopy: To view the lower colon for abnormalities.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): To evaluate pelvic organs.

Management and Treatment:

Surgical Treatment:

- Perineal Rectosigmoidectomy: To remove the prolapsed section.

- Laparoscopic Approach: To repair rectal prolapse.

Nonoperative Management:

- Gentle digital pressure to reduce the prolapse.

- Use of salt or sugar to decrease edema and facilitate reduction.

Non-surgical Management:

- Bulking agents, stool softeners, and suppositories or enemas for internal prolapse.

Complications:

- Infection

- Bleeding

- Intestinal injury

- Anastomotic leakage

- Bladder and sexual function alterations

- Constipation or outlet obstruction

- Fecal incontinence

- Urinary retention

- Medical complications from surgery (e.g., heart attack, pneumonia, deep venous thrombosis)

Prevention:

- Increase dietary fiber (at least five servings of fruits and vegetables daily).

- Drink 6 to 8 glasses of water daily.

- Regular exercise.

- Maintain a healthy weight or lose weight if necessary.

- Use stool softeners or laxatives if constipation is frequent.

very interesting, precise notes and easy to understand