Table of Contents

ToggleSpinal Cord Compression (SCC)

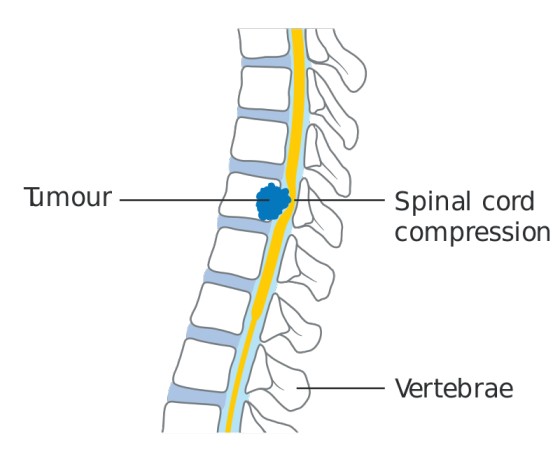

Spinal cord compression (SCC) results from processes that compress or displace arterial, venous, and cerebrospinal fluid spaces, as well as the cord itself.

Spinal cord compression (SCC) refers to the mechanical or pathological compression of the spinal cord, resulting in the displacement or obstruction of arterial, venous, and cerebrospinal fluid spaces, as well as direct cord involvement.

This compression can arise due to intrinsic or extrinsic causes, leading to varying degrees of neurological dysfunction.

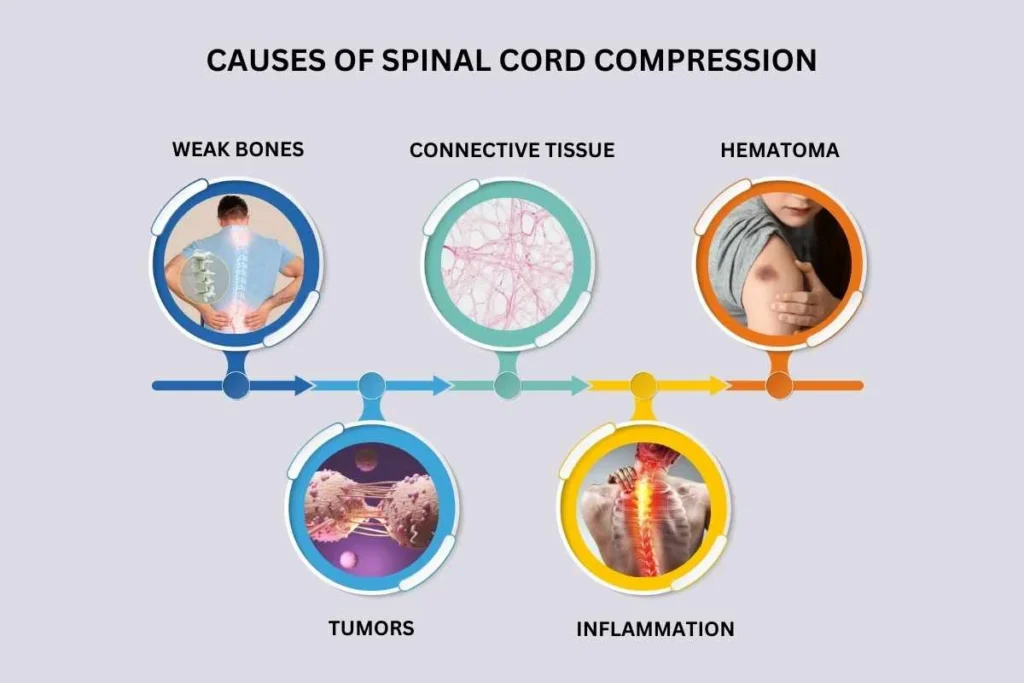

Etiology of Spinal Cord Compression

SCC can result from multiple conditions, broadly categorized into traumatic, neoplastic, degenerative, inflammatory, infectious, vascular, or iatrogenic causes.

1. Traumatic Causes

Trauma is a leading cause of SCC, often resulting from accidents, falls, or sports injuries. The injury can lead to:

- Vertebral fractures, commonly affecting the cervical spine.

- Facet joint dislocation, which can lead to spinal instability and compression.

- Complete transection of the spinal cord, resulting in irreversible neurological deficits.

- Brown-Séquard syndrome, a condition caused by spinal hemisection, often due to penetrating injuries. This results in ipsilateral motor weakness and contralateral loss of pain and temperature sensation.

2. Neoplastic Causes

Tumors, whether benign or malignant, can lead to SCC. These include:

- Primary spinal tumors (e.g., meningiomas, schwannomas, ependymomas).

- Metastatic tumors, commonly from lung, breast, prostate, and renal cancers.

- Hematologic malignancies such as lymphoma, multiple myeloma, and leukemia.

- Paraneoplastic syndromes leading to acute myelopathy.

- Meningeal carcinomatosis, in which cancer spreads to the meninges, causing extensive spinal cord involvement.

3. Degenerative Causes

Age-related degeneration of the spine can lead to compression via:

- Intervertebral disc herniation, commonly at L4-L5 and L5-S1, potentially causing cauda equina syndrome.

- Cervical disc herniation, which can result in myelopathy.

- Cervical spondylotic myelopathy, a progressive condition due to osteophyte formation, disc herniation, and ligamentum flavum hypertrophy.

4. Vascular Causes

- Epidural or subdural hematomas, typically occurring after trauma, spinal procedures, or in patients on anticoagulation therapy.

- Spinal cord infarction, which may occur due to atherosclerosis, embolism, or systemic hypotension.

- Arteriovenous malformations (AVMs), which can rupture and cause compression.

5. Inflammatory and Autoimmune Disorders

- Rheumatoid arthritis (RA): Weakening of the ligamentous structures around the odontoid peg can result in atlantoaxial subluxation and high cervical cord compression.

- Ankylosing spondylitis: Can cause severe kyphotic deformities leading to compression.

- Multiple sclerosis (MS): Can lead to spinal cord demyelination and secondary compression.

6. Infectious Causes

- Bacterial infections, such as vertebral osteomyelitis and discitis, can result in spinal cord compression.

- Tuberculosis (Pott’s disease), a chronic infection that can cause vertebral collapse and epidural abscess formation.

- Fungal infections, such as aspergillosis or cryptococcosis, are more common in immunocompromised patients.

7. Iatrogenic and Miscellaneous Causes

- Complications from spinal surgery, including epidural fibrosis and post-operative hematomas.

- Spinal manipulation: Though rare, chiropractic or osteopathic manipulation can lead to spinal injury.

- Ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL): A condition seen in some Asian populations, leading to spinal canal narrowing.

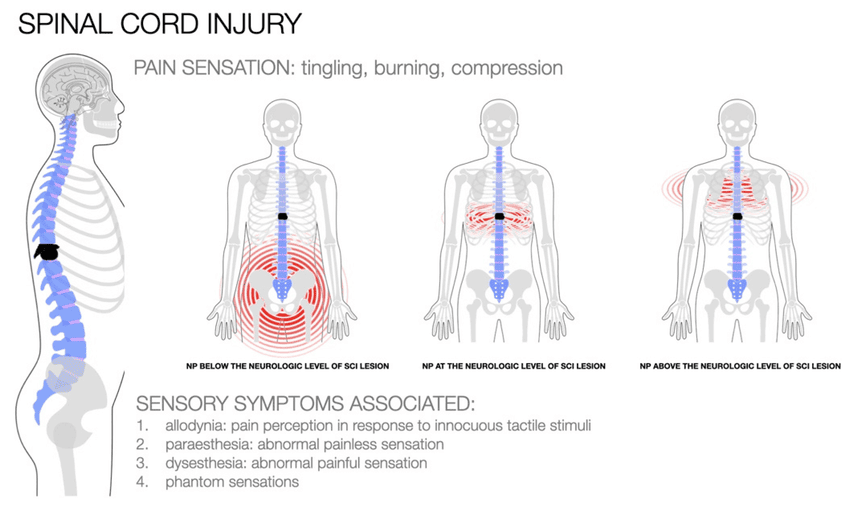

Clinical Presentation of Spinal Cord Compression

The symptoms of SCC vary depending on the location, severity, and rate of onset.

Neurological Symptoms

- Motor dysfunction: Progressive weakness, difficulty with fine motor tasks, clumsiness, and gait disturbances.

- Sensory deficits: Loss of pain, temperature, proprioception, and vibration sensation, often in a dermatomal pattern.

- Autonomic dysfunction: Loss of bladder, bowel, and sexual function.

- Lhermitte’s sign: An electric shock-like sensation radiating down the spine and limbs upon neck flexion.

Neurological Signs

Upper motor neuron (UMN) signs (seen in spinal cord compression above the conus medullaris):

- Hyperreflexia

- Clonus

- Spasticity

- Positive Babinski sign (upgoing plantar reflex)

Lower motor neuron (LMN) signs (seen in cauda equina syndrome or nerve root compression):

- Muscle atrophy

- Hyporeflexia

- Flaccid paralysis

Regional Effects of Compression

- Cervical spine involvement: Can cause quadriplegia. Lesions at C3-C5 affect the phrenic nerve, leading to respiratory failure.

- Thoracic spine involvement: Can cause paraplegia.

- Lumbar spine involvement: Can affect the L4-S1 nerve roots, leading to radicular pain and cauda equina syndrome.

Autonomic Dysfunction

- Neurogenic shock: Loss of sympathetic tone leading to hypotension and bradycardia.

- Paralytic ileus: Gastrointestinal stasis due to autonomic dysfunction.

- Urinary retention: Loss of bladder control, leading to overflow incontinence.

- Priapism: A sustained, painful erection due to autonomic dysfunction.

- Loss of thermoregulation: Impaired ability to control body temperature below the lesion level.

Diagnosis and Investigations

A thorough diagnostic workup is necessary to determine the underlying cause of SCC.

Laboratory Tests

- Complete blood count (CBC): To assess for anemia, infection, or malignancy.

- Inflammatory markers: ESR and CRP can be elevated in infections and inflammatory conditions.

- Coagulation profile: Important if a hematoma is suspected.

- Renal function and electrolytes: To assess for dehydration and metabolic abnormalities.

Imaging

- MRI of the entire spine (gold standard): Provides detailed visualization of the spinal cord, nerve roots, and soft tissues.

- CT scan with myelography: Useful when MRI is contraindicated (e.g., pacemakers, certain implants).

- X-rays: Can detect fractures, vertebral instability, and degenerative changes.

Electrophysiological Studies

- Somatosensory evoked potentials (SSEP): Can assess functional impairment of the spinal cord.

- Electromyography (EMG) and nerve conduction studies (NCS): Useful in distinguishing SCC from peripheral neuropathy.

Management of Spinal Cord Compression (SCC)

Aims of Management

Effective management of spinal cord compression (SCC) requires a multidisciplinary approach aimed at;

- stabilizing the spine,

- preserving neurological function,

- alleviating pain, and addressing the underlying cause.

1. Immediate Management and Supportive Care

Spinal Stability and Nursing Care

- Keep the patient flat with the spine in a neutral alignment using logrolling techniques or specialized turning beds. This prevents further injury until spinal and neurological stability are confirmed.

- Use rigid cervical collars or spinal orthoses for immobilization in cases of suspected instability.

Corticosteroid Therapy

- Dexamethasone is recommended to reduce spinal cord edema and inflammation.

- A typical regimen includes a loading dose (e.g., 16 mg IV) followed by gradual tapering over days to weeks depending on the underlying condition.

- Contraindications: Active infections, uncontrolled diabetes, gastrointestinal ulcers.

Management of Hemodynamic Instability

- Postural hypotension should be managed with gradual position changes, compression garments (e.g., abdominal binders, elastic stockings), and devices to enhance venous return.

- Avoid overhydration, as fluid overload can exacerbate pulmonary complications.

Bladder and Bowel Management

- Urinary catheterization is often required for neurogenic bladder dysfunction to prevent urinary retention and infections.

- Bowel management includes laxatives and scheduled bowel programs to prevent constipation or incontinence.

Respiratory Support

- Patients with high cervical cord injuries (above C3-C5) may require mechanical ventilation due to diaphragm paralysis.

- Breathing exercises, assisted coughing, suctioning, and chest physiotherapy help prevent aspiration pneumonia and secretion retention.

Psychosocial and Emotional Support

- Patients may experience anxiety, depression, or distress due to functional limitations.

- Counseling, psychiatric support, and spiritual care should be integrated into the treatment plan.

2. Pain Management

Pain control is essential for improving the patient’s quality of life and may involve a combination of pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic approaches.

Pharmacologic Pain Management

- First-line therapy: NSAIDs, acetaminophen.

- Moderate to severe pain: Opioids (e.g., morphine, oxycodone, fentanyl patches).

- Neuropathic pain: Gabapentin, pregabalin, or tricyclic antidepressants (e.g., amitriptyline).

- Bisphosphonates (e.g., zoledronic acid, pamidronate) for pain relief in cases of vertebral involvement from myeloma or metastatic breast/prostate cancer.

- Corticosteroids also have analgesic effects, particularly in malignancy-related SCC.

Advanced Pain Control Strategies

For intractable pain, specialized pain procedures may be required:

- Epidural analgesia or spinal nerve blocks.

- Palliative radiotherapy for pain relief in metastatic SCC.

- Vertebroplasty or kyphoplasty for vertebral compression fractures causing severe pain.

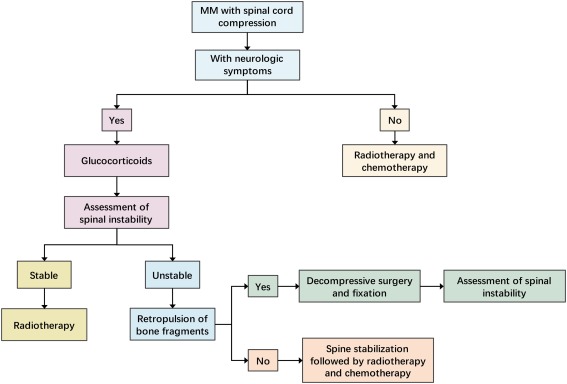

3. Definitive Treatment

Timing of Intervention

- Early intervention is crucial—treatment should ideally begin before the patient loses ambulation or experiences severe neurological deterioration.

- In malignant SCC, interventions should commence within 24 hours of diagnosis.

Surgical Intervention

Surgery is often indicated for mechanical instability, progressive neurological deficits, or refractory pain. Common procedures include:

- Laminectomy (posterior decompression ± internal fixation).

- Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF) for cervical compression.

- Vertebral corpectomy with spinal reconstruction in cases of extensive vertebral destruction.

- Spinal stabilization using rods, screws, or cages to restore structural integrity.

Radiotherapy

- Indicated in metastatic SCC or cases where surgery is contraindicated.

- External beam radiotherapy (EBRT) is the most common modality.

- Stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) delivers precise high-dose radiation for certain tumors.

Chemotherapy and Targeted Therapy

- Used in cases of hematologic malignancies (e.g., lymphoma, multiple myeloma).

- Hormonal therapy for SCC due to hormone-sensitive cancers (e.g., prostate, breast cancer).

4. Discharge Planning and Rehabilitation

Recovery from SCC often requires long-term multidisciplinary rehabilitation to improve function and quality of life.

Comprehensive Discharge Planning

- Assess home safety and support systems.

- Train caregivers and family members in patient mobility, catheter care, and wound prevention.

- Coordinate with community-based rehabilitation services.

- Ensure follow-up appointments with neurologists, physiatrists, and oncologists (if applicable).

Physical Rehabilitation

- Early mobilization and physiotherapy to prevent muscle atrophy and improve strength.

- Assistive devices (wheelchairs, walkers, braces) as needed.

- Occupational therapy to enhance daily functioning.

Psychological and Social Support

- Coping mechanisms for disability adaptation.

- Peer support groups for spinal cord injury (SCI) patients.

Cancer Screening and SCC Detection

Patients with known malignancies should undergo routine screening for SCC to ensure early detection.

Red Flags for Spinal Metastases in Cancer Patients

- Persistent thoracic or cervical spine pain.

- Progressive, unrelenting lumbar spinal pain.

- Spinal pain exacerbated by movement, coughing, or straining.

- Nocturnal spinal pain that disrupts sleep.

- Localized spinal tenderness.

Symptoms Suggestive of Metastatic SCC

- Radicular pain.

- Limb weakness or gait disturbances.

- Sensory loss or paresthesia.

- Bladder or bowel dysfunction.

- Neurological signs of cord or cauda equina compression.

Imaging Guidelines

MRI of the whole spine is the gold standard for diagnosis.

- If spinal metastases are suspected: MRI within one week.

- If SCC is suspected: MRI within 24 hours.

- Urgent MRI (out of hours) for patients requiring emergency intervention.

Complications of SCC

- Permanent paraplegia or quadriplegia.

- Autonomic dysfunction (hypotension, neurogenic bladder).

- Chronic neuropathic pain.

- Pressure ulcers from prolonged immobility → Requires frequent repositioning.

- Osteoporosis and fractures due to prolonged immobilization.

- Aspiration pneumonia, atelectasis, ventilation-perfusion mismatch.

- Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).

- Depression and anxiety due to loss of independence.

- Reduced participation in daily activities and social isolation.

Prognosis of SCC

- Spinal cord regeneration is limited, so prognosis depends largely on the severity of the initial injury and timeliness of treatment.

- Ambulatory status at the time of diagnosis is a key predictor of recovery—patients who are ambulatory at diagnosis have a significantly better prognosis.

- Preventing complications (e.g., infections, pressure sores) is crucial for long-term outcomes.

- Underlying etiology (e.g., trauma vs. malignancy) determines overall survival.

In cases of malignant SCC, prognosis depends on:

- Primary tumor type and response to treatment.

- Presence of metastases elsewhere.

- Effectiveness of pain and symptom management.

Nursing care

- Nurse the patient flat with the spine in neutral alignment (eg, using logrolling or turning beds) until spinal stability and neurological stability are ensured.

- Give a course of dexamethasone unless contra-indicated until a definitive treatment plan is made.

- Manage postural hypotension with positioning and devices to improve venous return; avoid overhydration.

- Insert a catheter to manage bladder dysfunction.

- Use breathing exercises, assisted coughing, and suctioning to clear airway secretions.

- Offer and provide psychological and spiritual support as needed (including after discharge).

- Analgesia, palliative radiotherapy, spinal orthoses, vertebroplasty or kyphoplasty, or spinal stabilization surgery may be required for pain control.

- Bisphosphonates should be offered to all patients with vertebral involvement from myeloma and breast cancer and to patients with prostate cancer in whom conventional analgesia is inadequate.

- Specialized pain control procedures may be needed for intractable pain (eg, epidural analgesia).

- If definitive treatment of the cord compression is appropriate, it should be started before patients lose the ability to walk or before other neurological deterioration occurs, and ideally within 24 hours.

- Definitive treatment may be using surgery (eg, laminectomy, posterior decompression ± internal fixation) or using radiotherapy.

- Discharge should be fully planned and community-based rehabilitation and support should be available when the patient returns home. This includes support and any necessary training of carers and families.

Itz a very good and summarized data

It’s precise and easy to read

Good work

Well summarized

Thanks alot