Pneumonia remains a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in children worldwide, especially in developing countries. Its epidemiology and etiology differ significantly from adults, largely due to variations in immune system maturity, exposure patterns, and anatomical differences.

Pneumonia is an acute inflammatory condition of the lung parenchyma caused by an infection.

- lung parenchyma is the the functional tissue of the lungs, specifically the alveoli and bronchioles.

This inflammation leads to the filling of the alveolar spaces with exudate, cells, and fluid, a process known as consolidation. This consolidation impairs gas exchange, leading to symptoms such as cough, fever, chills, and difficulty breathing.

In simpler terms, pneumonia is an infection that inflames the air sacs in one or both lungs. The air sacs may fill with fluid or pus (purulent material), causing cough with phlegm or pus, fever, chills, and trouble breathing.

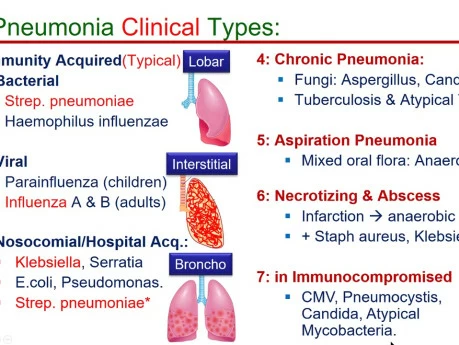

Pneumonia can be classified in various ways, each providing a different lens through which to understand its cause, presentation, and management.

This classification focuses on the specific microorganism responsible for the infection.

- Bacterial Pneumonia: The most common type, often more severe than viral pneumonia.

- Common Pathogens:

- Streptococcus pneumoniae (Pneumococcus): The most frequent cause of community-acquired bacterial pneumonia.

- Haemophilus influenzae.

- Staphylococcus aureus (including MRSA).

- Klebsiella pneumoniae.

- Mycoplasma pneumoniae (often called "walking pneumonia" due to milder symptoms).

- Chlamydophila pneumoniae.

- Legionella pneumophila (Legionnaires' disease).

- Common Pathogens:

- Viral Pneumonia: Often milder than bacterial pneumonia but can be severe, especially in infants, elderly, and immunocompromised individuals.

- Common Pathogens:

- Influenza viruses (Types A and B).

- Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV).

- Adenoviruses.

- Parainfluenza viruses.

- Human Metapneumovirus.

- Coronaviruses (e.g., SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2).

- Common Pathogens:

- Fungal Pneumonia: Less common, usually affecting individuals with weakened immune systems or those exposed to large amounts of fungi in the environment.

- Common Pathogens:

- Pneumocystis jirovecii (PCP pneumonia, common in HIV/AIDS patients).

- Histoplasma capsulatum (Histoplasmosis).

- Coccidioides immitis (Coccidioidomycosis or Valley Fever).

- Blastomyces dermatitidis (Blastomycosis).

- Aspergillus species.

- Common Pathogens:

- Parasitic Pneumonia: Rare, caused by parasites, usually seen in immunocompromised individuals or those who have traveled to endemic areas.

- Common Pathogens:

- Toxoplasma gondii.

- Strongyloides stercoralis.

- Common Pathogens:

- Aspiration Pneumonia: Occurs when foreign material (e.g., food, liquid, vomit, stomach contents) is inhaled into the lungs, leading to inflammation and often secondary bacterial infection.

- Causes: Impaired swallowing mechanisms, altered consciousness, gastroesophageal reflux.

- Chemical Pneumonia (Pneumonitis): Lung inflammation caused by inhaling irritating chemicals or toxic gases, rather than an infectious agent. This is not an infection but can predispose to one.

- Causes: Inhalation of smoke, noxious fumes, or gastric acid.

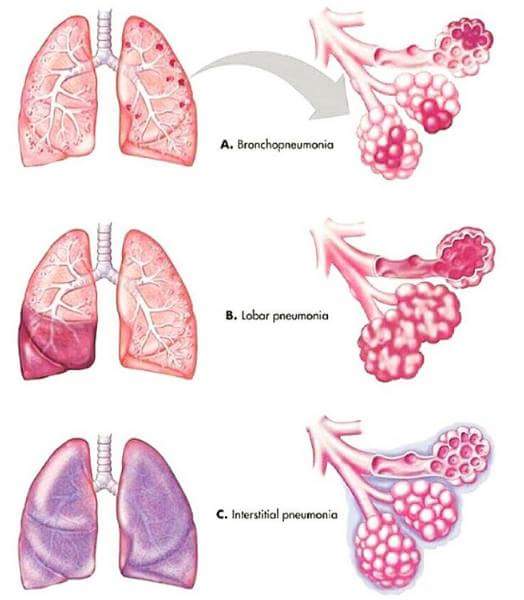

This classification describes the pattern of lung involvement as seen on chest imaging.

- Lobar Pneumonia: Affects a large, continuous area of an entire lobe of a lung. Often caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae.

- Appearance: Typically seen as a dense, homogeneous consolidation on chest X-ray.

- Bronchopneumonia (or Lobular Pneumonia): Characterized by patchy consolidation centered around the bronchi and bronchioles, often affecting multiple lobes. More common in infants, young children, and the elderly.

- Appearance: Patchy infiltrates on chest X-ray, often bilateral and basal.

- Interstitial Pneumonia: Involves the interstitial spaces of the lung (the tissue between the alveoli and capillaries), rather than primarily the air sacs. More commonly associated with viral or atypical bacterial infections.

- Appearance: Reticular or reticulonodular patterns on chest X-ray.

- Miliary Pneumonia: A form of pneumonia characterized by the wide dissemination of an infectious agent (Mycobacterium tuberculosis) throughout the lung tissue in small, discrete lesions resembling millet seeds.

- Appearance: Fine, diffuse nodular infiltrates throughout both lungs on chest X-ray.

This classification refers to the time course of the illness.

- Acute Pneumonia: Rapid onset and progression of symptoms, typically resolving within days to a few weeks with appropriate treatment. Most common form.

- Chronic Pneumonia: Persistent symptoms and radiological findings lasting for weeks to months, or even longer. Often associated with specific pathogens (e.g., Mycobacterium tuberculosis, fungi) or underlying conditions.

This is one of the most clinically relevant classifications, as it guides initial empiric treatment decisions.

- Community-Acquired Pneumonia (CAP): Pneumonia acquired outside of hospitals or long-term care facilities.

- Common Pathogens: Streptococcus pneumoniae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydophila pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, influenza virus.

- Hospital-Acquired Pneumonia (HAP) / Nosocomial Pneumonia: Pneumonia that develops 48 hours or more after hospital admission and was not incubating at the time of admission.

- Common Pathogens: Often more virulent and antibiotic-resistant bacteria, such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Klebsiella species, Escherichia coli.

- Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia (VAP): A subtype of HAP that develops in patients who have been mechanically ventilated for more than 48 hours.

- Common Pathogens: Similar to HAP, often highly resistant organisms.

The etiology refers to the specific agents or organisms responsible for causing pneumonia. As discussed in Objective 1, these can be broadly categorized.

These are the most frequent causes of pneumonia, especially bacterial pneumonia.

- Streptococcus pneumoniae (Pneumococcus):

- Description: The leading cause of community-acquired bacterial pneumonia (CAP) in all age groups, particularly in adults.

- Characteristics: Gram-positive coccus, typically arranged in pairs (diplococci). Has a polysaccharide capsule that protects it from phagocytosis.

- Risk Factors: Old age, chronic lung disease, recent viral infection, immunocompromised status.

- Haemophilus influenzae:

- Description: A common cause of both CAP and HAP, especially in individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or other underlying lung conditions.

- Characteristics: Gram-negative coccobacillus.

- Risk Factors: COPD, cystic fibrosis, alcoholism.

- Staphylococcus aureus:

- Description: Can cause severe pneumonia, often seen as HAP or as a complication of viral infections (e.g., influenza). Methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) is a significant concern, especially in VAP and HCAP.

- Characteristics: Gram-positive coccus, often arranged in clusters. Produces various toxins.

- Risk Factors: Recent influenza, injection drug use, skin/soft tissue infection, hospitalization, surgical procedures.

- Klebsiella pneumoniae:

- Description: A common cause of HAP and, less frequently, severe CAP, particularly in individuals with alcoholism or diabetes. Known for causing "currant jelly" sputum.

- Characteristics: Gram-negative rod, often encapsulated.

- Risk Factors: Alcoholism, diabetes, chronic lung disease, hospitalization.

- Pseudomonas aeruginosa:

- Description: A significant cause of HAP and VAP, particularly in immunocompromised patients, those with cystic fibrosis, or prolonged hospital stays. Difficult to treat due to antibiotic resistance.

- Characteristics: Gram-negative rod.

- Risk Factors: Cystic fibrosis, bronchiectasis, mechanical ventilation, broad-spectrum antibiotic use, immunocompromised state.

- Mycoplasma pneumoniae:

- Description: A common cause of "atypical pneumonia" or "walking pneumonia" in young adults and school-aged children. Causes milder, but prolonged, symptoms.

- Characteristics: Lacks a cell wall, making it resistant to many common antibiotics (e.g., penicillin).

- Chlamydophila pneumoniae:

- Description: Another cause of atypical pneumonia, often with milder symptoms.

- Characteristics: Obligate intracellular bacterium.

- Legionella pneumophila:

- Description: Causes Legionnaires' disease, a severe form of pneumonia often associated with contaminated water sources (e.g., air conditioning systems, hot tubs).

- Characteristics: Gram-negative rod, fastidious growth requirements.

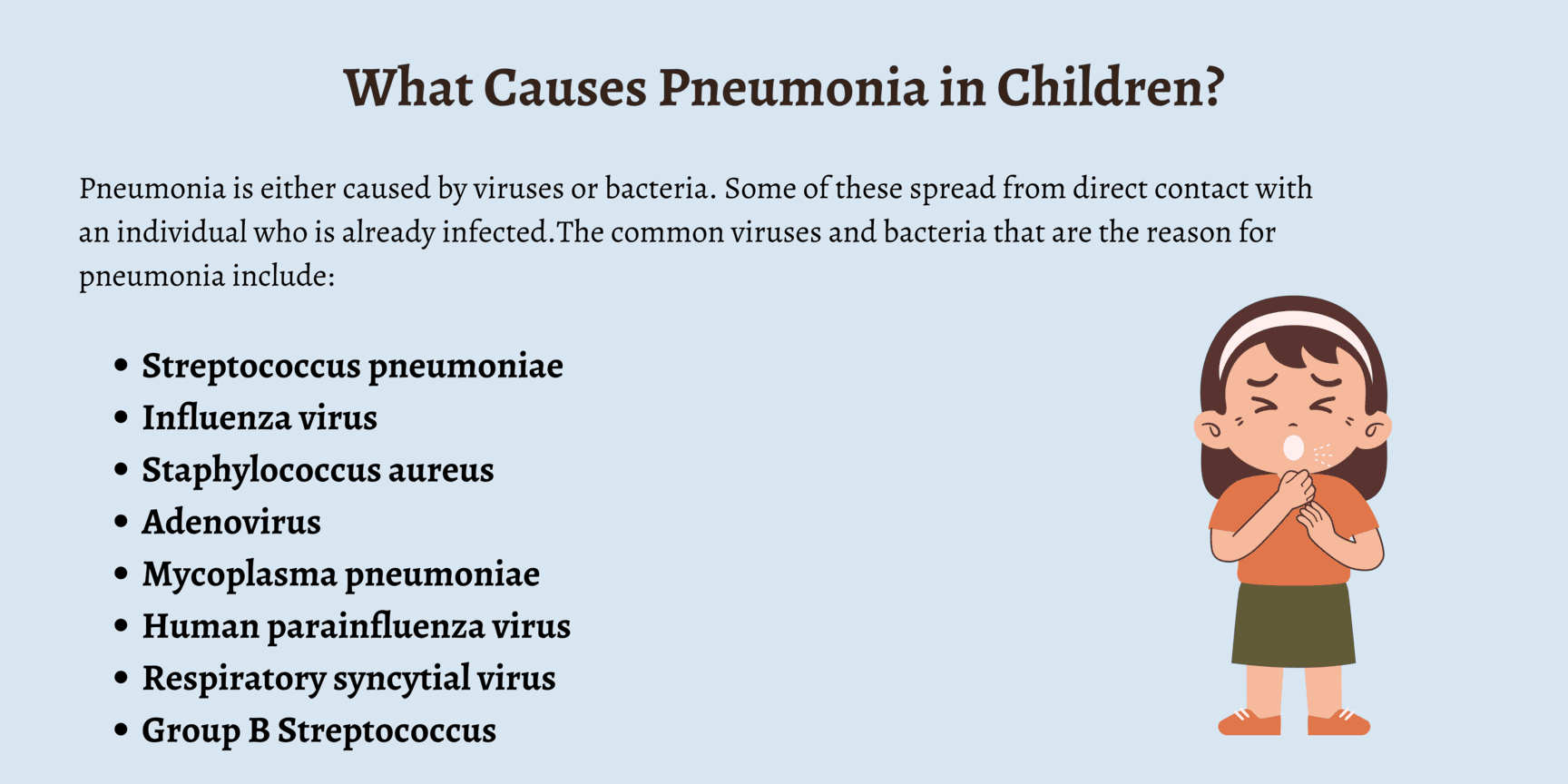

Viruses are a very common cause of pneumonia, especially in children. They can also predispose to secondary bacterial infections.

- Influenza Viruses (A and B): Seasonal epidemics cause widespread respiratory illness, including primary viral pneumonia and often secondary bacterial pneumonia.

- Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV): The most common cause of lower respiratory tract infections in infants and young children, often leading to bronchiolitis and pneumonia.

- Adenoviruses: Can cause a range of respiratory illnesses, including pneumonia, particularly in children and immunocompromised individuals.

- Parainfluenza Viruses: Common cause of croup, but can also cause bronchiolitis and pneumonia, especially in children.

- Coronaviruses (e.g., SARS-CoV-2): Various coronaviruses can cause respiratory infections, with SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) being a notable cause of severe viral pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).

More prevalent in immunocompromised individuals or specific geographic regions.

- Pneumocystis jirovecii: Causes Pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP), a common and severe opportunistic infection in individuals with HIV/AIDS.

- Endemic Fungi (e.g., Histoplasma capsulatum, Coccidioides immitis, Blastomyces dermatitidis): Found in specific geographic areas. Exposure to spores can lead to pneumonia, especially in immunocompromised individuals.

- Aspergillus species: Can cause invasive aspergillosis, a severe pneumonia, primarily in severely immunocompromised patients (e.g., transplant recipients, leukemia patients).

Not an infectious agent itself, but the aspiration of acidic gastric contents or other foreign material can cause a severe chemical pneumonitis, which then often becomes secondarily infected by oral flora (anaerobic bacteria).

Pathogenesis describes the sequence of events that leads to the development of pneumonia, from initial exposure to clinical symptoms.

The respiratory tract has several protective mechanisms to prevent infection:

- Upper Airway Filtration: Nasal hairs, turbinates, and mucous membranes filter out large particles.

- Epiglottis and Cough Reflex: Protect the lower airways from aspiration.

- Mucociliary Escalator: Ciliated epithelial cells line the trachea and bronchi, moving mucus (which traps pathogens) upwards for expectoration or swallowing.

- Alveolar Macrophages: Phagocytic cells in the alveoli that engulf and destroy pathogens and debris.

- Humoral and Cellular Immunity: Antibodies (IgA, IgG) and T lymphocytes provide specific immunity.

Pneumonia develops when pathogens overcome or bypass these host defenses.

- Aspiration (Most Common): Microaspiration of oropharyngeal secretions containing pathogens is the most frequent route. This happens constantly in small amounts, but typically the host defenses clear them. Impaired consciousness, dysphagia, or presence of a nasogastric tube increases the risk of significant aspiration.

- Inhalation: Airborne pathogens (e.g., viruses, Mycoplasma, Legionella, fungi) can be inhaled directly into the lower respiratory tract.

- Hematogenous Spread: Pathogens from a distant site of infection (e.g., endocarditis, IV drug use, abdominal sepsis) can travel through the bloodstream to the lungs.

- Direct Spread: Less common, but can occur from contiguous infected sites (e.g., empyema spreading to lung, trauma).

Once pathogens reach the lower respiratory tract and evade local defenses, a series of events leads to inflammation and consolidation:

- Colonization and Multiplication: Pathogens colonize the alveoli and/or terminal bronchioles and begin to multiply.

- Immune Response and Inflammation:

- Alveolar Macrophages: Are typically the first line of defense. If overwhelmed, they release cytokines (e.g., TNF-alpha, IL-1, IL-6, IL-8).

- Neutrophil Recruitment: These cytokines attract neutrophils from the bloodstream into the alveolar spaces.

- Increased Vascular Permeability: The inflammatory response causes vasodilation and increased permeability of the alveolar-capillary membrane.

- Fluid Exudation and Consolidation:

- Plasma fluid, red blood cells, and fibrin leak into the alveolar spaces.

- Neutrophils and bacteria fill the alveoli.

- This mixture of fluid, cells, and debris leads to the characteristic consolidation seen in pneumonia, where the lung tissue becomes dense and airless.

- Impaired Gas Exchange:

- The consolidated alveoli can no longer participate in gas exchange.

- This leads to ventilation-perfusion mismatch (areas are perfused but not ventilated), resulting in hypoxemia (low blood oxygen).

- The increased work of breathing due to decreased lung compliance and airway obstruction can also lead to hypercapnia (high blood carbon dioxide) in severe cases.

- Tissue Damage: The inflammatory process and release of bacterial toxins can cause damage to the alveolar and bronchial epithelial cells, impairing mucociliary function and further propagating inflammation.

- Resolution: With effective immune response and/or antibiotic treatment, the inflammation subsides, macrophages clear cellular debris, and the exudate is reabsorbed, allowing the lung to return to normal function.

The pathogens responsible for pneumonia vary significantly by age group.

- Group B Streptococcus (GBS): Common cause of early-onset neonatal sepsis and pneumonia.

- Gram-negative enteric bacilli: Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae.

- Listeria monocytogenes.

- Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus): Increasingly common.

- Haemophilus influenzae (non-typeable or type b if unvaccinated).

- Staphylococcus aureus: Can cause severe disease.

- Chlamydia trachomatis: Can cause afebrile pneumonia, often associated with conjunctivitis, transmitted from mother during birth. Presents at 2-12 weeks of age.

- Bordetella pertussis (whooping cough): Can cause severe pneumonia, especially in unvaccinated infants.

- Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV): The leading cause of bronchiolitis and pneumonia in infants.

- Parainfluenza viruses: (Types 1, 2, 3).

- Adenovirus: Can cause severe and prolonged disease.

- Influenza viruses: (A and B).

- Human Metapneumovirus.

- RSV, Influenza, Parainfluenza, Adenovirus, Human Metapneumovirus, Rhinovirus.

- Streptococcus pneumoniae (Pneumococcus): Remains the most frequent bacterial cause.

- Haemophilus influenzae (non-typeable).

- Staphylococcus aureus (including MRSA).

- Streptococcus pyogenes (Group A Strep): Less common but can cause severe pneumonia.

- Mycoplasma pneumoniae: Becomes more common in this age group, though classically associated with school-aged children.

- Mycoplasma pneumoniae: The most common cause of "atypical pneumonia" or "walking pneumonia."

- Chlamydophila pneumoniae.

- Streptococcus pneumoniae.

- Staphylococcus aureus (including MRSA).

- Haemophilus influenzae.

- Streptococcus pyogenes.

- Influenza A and B.

- Adenovirus.

Recognize age-specific manifestations and indicators of severity to ensure timely intervention.

- < 2 months: ≥ 60 breaths/min

- 2-11 months: ≥ 50 breaths/min

- 1-5 years: ≥ 40 breaths/min

- 5 years: ≥ 20 breaths/min

- Respiratory Distress: Tachypnea (often the earliest sign), grunting, nasal flaring, retractions (subcostal, intercostal, suprasternal).

- Apnea: Pauses in breathing, especially in premature infants.

- Cyanosis (bluish discoloration) or pallor.

- Lethargy, irritability, hypotonia.

- Poor feeding, vomiting.

- Temperature instability (hypothermia is common, fever less so).

- Jaundice.

- Tachypnea: Always a critical sign.

- Retractions: Subcostal, intercostal, suprasternal, supraclavicular.

- Nasal Flaring.

- Grunting: Short, low-pitched sounds during expiration, attempting to increase end-expiratory pressure.

- Cough: Can be prominent, may be paroxysmal, especially with Pertussis or viral causes like RSV.

- Fever.

- Poor feeding, decreased activity.

- Wheezing (more common with viral pneumonia/bronchiolitis).

- Tachypnea.

- Cough: Often harsh and persistent.

- Fever.

- Dyspnea, increased work of breathing.

- Lethargy, irritability, decreased playfulness.

- Decreased appetite.

- Abdominal pain: Can be a presenting complaint, particularly with lower lobe pneumonia irritating the diaphragm.

- Cough: Can be productive with sputum, especially in bacterial pneumonia.

- Fever and Chills.

- Dyspnea / Shortness of Breath.

- Pleuritic Chest Pain: Sharp pain worsened by breathing or coughing.

- Headache, malaise, myalgia.

- Abdominal pain.

- "Atypical" Pneumonia (e.g., Mycoplasma pneumoniae): Often presents with more insidious onset, low-grade fever, persistent dry cough, headache, and malaise, sometimes called "walking pneumonia."

Rapid recognition of these signs is critical for determining the need for hospitalization and intensive care.

- Severe Tachypnea (respiratory rate significantly above age-appropriate limits).

- Severe Retractions (all types, especially supraclavicular, tracheal tug).

- Grunting.

- Nasal Flaring.

- Central Cyanosis: Bluish discoloration of the tongue, lips, and nail beds, indicating hypoxemia.

- Head Bobbing: Especially in infants.

- Onset and duration of symptoms (fever, cough, respiratory distress, feeding difficulties).

- Exposure history (sick contacts, daycare, travel).

- Vaccination status.

- Risk factors (prematurity, underlying medical conditions).

- Medication history.

- General Appearance: Alertness, activity level, signs of distress.

- Vital Signs: Respiratory rate (most sensitive sign of pneumonia), heart rate, temperature, blood pressure.

- Respiratory Examination:

- Inspection: Work of breathing (retractions, nasal flaring, grunting), cyanosis, symmetry of chest movement.

- Palpation: Tactile fremitus (may be increased over consolidation, but difficult in young children).

- Percussion: Dullness over consolidated areas or pleural effusion.

- Auscultation:

- Crackles (rales): Suggestive of alveolar inflammation/fluid.

- Bronchial breath sounds: Over consolidated lung tissue.

- Wheezing: More common in viral causes or with underlying reactive airway disease.

- Decreased or absent breath sounds: May indicate consolidation or pleural effusion.

- Other Systems: Assess for dehydration, cardiac involvement, neurological status.

- Essential non-invasive test in all children suspected of having pneumonia.

- Measures oxygen saturation (SpO2). Hypoxemia (SpO2 < 90-92% on room air) is a strong indicator of severity and often guides hospitalization and oxygen therapy.

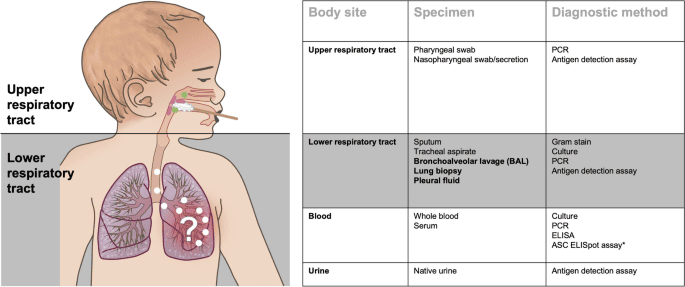

- Typically not recommended for routine diagnosis of uncomplicated community-acquired pneumonia in children who can be managed as outpatients and whose diagnosis is clear clinically.

- Recommended for:

- Children with severe pneumonia.

- Uncertain diagnosis, or if differential diagnoses like foreign body aspiration are considered.

- Failure to respond to initial empiric therapy.

- Suspicion of complications (e.g., pleural effusion, empyema, abscess).

- Recurrent pneumonia.

- Lobar Consolidation: Suggests bacterial pneumonia.

- Interstitial Infiltrates: More characteristic of viral or atypical pneumonia.

- Bronchial Wall Thickening/Peribronchial Cuffing: Common in viral infections.

- Pleural Effusion, Empyema, Pneumothorax: Indicate complications.

- Hyperinflation: Common in viral bronchiolitis.

- Cannot reliably distinguish between bacterial and viral pneumonia.

- Poor correlation between radiological findings and clinical severity.

- Radiation exposure.

- Generally NOT recommended for routine CAP in outpatient settings.

- Consider for: Hospitalized children with severe pneumonia, immunocompromised children, suspicion of bacteremia. Low yield (typically < 1-2%).

- Not routinely recommended for uncomplicated CAP.

- May show leukocytosis with neutrophilia in bacterial infection, or lymphocytosis in viral infection, but findings can overlap and are not definitive.

- May be elevated in bacterial infections, but also in severe viral infections.

- Not routinely used for initial diagnosis but can sometimes aid in differentiating bacterial from viral, or monitoring response to treatment.

- Recommended for: All hospitalized infants and young children with suspected viral pneumonia/bronchiolitis (e.g., RSV, influenza, adenovirus, parainfluenza).

- Important for infection control, cohorting patients, and avoiding unnecessary antibiotic use.

- Does not rule out bacterial co-infection.

- Difficult to obtain in young children, often contaminated by upper airway flora. Not routinely recommended.

- If pleural effusion is present, diagnostic thoracentesis may be performed to identify the pathogen and guide treatment for empyema.

- Consider in children with persistent or recurrent pneumonia, or risk factors for tuberculosis.

- Can be useful for retrospective diagnosis, but acute and convalescent titers are needed, so not helpful for acute management.

Many conditions can mimic pneumonia in children due to similar respiratory symptoms.

- Upper Respiratory Tract Infection (URI) / Common Cold: Often presents with cough, rhinorrhea, low-grade fever. Absence of tachypnea and significant work of breathing usually differentiates it from pneumonia.

- Bronchiolitis: Common in infants < 2 years, primarily caused by RSV. Presents with cough, rhinorrhea, tachypnea, prominent wheezing, and crackles. Often difficult to distinguish clinically from viral pneumonia, and they can coexist.

- Asthma Exacerbation / Reactive Airway Disease: Wheezing, cough, dyspnea. History of recurrent episodes or triggers may point to asthma.

- Foreign Body Aspiration: Sudden onset of choking, coughing, dyspnea, particularly in toddlers. Can lead to unilateral wheezing or recurrent localized pneumonia. A high index of suspicion is needed. CXR may show unilateral hyperinflation or atelectasis.

- Croup (Laryngotracheobronchitis): "Barking" cough, inspiratory stridor, hoarseness, typically worse at night. Primarily affects the upper airway.

- Pertussis (Whooping Cough): Prolonged paroxysmal cough, often followed by a "whooping" sound and post-tussive emesis. Can cause severe pneumonia in infants.

- Heart Failure: Tachypnea, cough, poor feeding, hepatomegaly, often in infants with congenital heart disease. CXR may show cardiomegaly and pulmonary edema.

- Pulmonary Edema: Can result from fluid overload, acute kidney injury, or cardiac dysfunction.

- Pleural Effusion (without underlying pneumonia): Can cause dyspnea and decreased breath sounds, but usually related to other causes (e.g., malignancy, autoimmune disease).

- Tuberculosis: Consider in endemic areas or with risk factors, especially for persistent cough, failure to thrive, or abnormal CXR.

Aims: The medical management of pediatric pneumonia aims to eradicate the causative pathogen, alleviate symptoms, prevent complications, and provide supportive care tailored to the child's age and severity of illness.

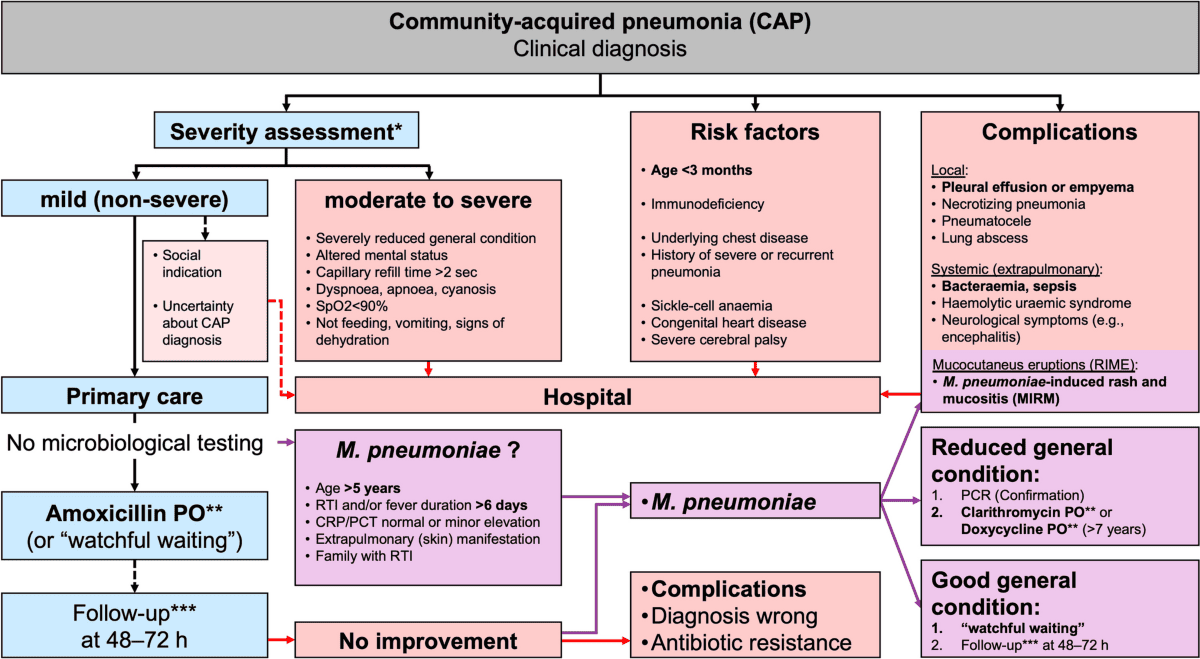

- Assessment of Severity: The initial step is to assess the severity of pneumonia to determine the appropriate level of care (outpatient vs. inpatient, general ward vs. ICU). Key indicators include respiratory distress (tachypnea, retractions, grunting, nasal flaring), hypoxemia (SpO2 < 90-92%), inability to feed, lethargy, and signs of dehydration.

- Empiric Antibiotic Therapy:

- Rationale: While viral etiologies are common, bacterial pneumonia can be severe and life-threatening. Clinical signs often overlap, and rapid viral testing may not be immediately available. Therefore, empiric antibiotic treatment is crucial, especially in moderate to severe cases, to cover likely bacterial pathogens.

- De-escalation: Once a pathogen is identified (e.g., strong evidence of viral infection) or if the child rapidly improves, antibiotics may be discontinued or narrowed.

- Supportive Care: This is the cornerstone of management for all types of pneumonia (viral and bacterial) and focuses on maintaining oxygenation, hydration, nutrition, and comfort.

The choice of antibiotic depends on the child's age, severity of illness, local resistance patterns, and immunization status.

- For Infants under 2 months with Severe Pneumonia (Hospitalized):

- First-line combination: Ampicillin (150-200 mg/kg/day in divided doses IV) plus Gentamycin (5-6 mg/kg/day IV).

- Rationale: Covers common neonatal pathogens like Group B Streptococcus and Gram-negative enteric bacilli.

- Alternative if Penicillin Not Available/Suitable: Cefotaxime (IV).

- If Condition Does Not Improve/Suspicion of S. aureus: Add Cloxacillin (IV) to cover Staphylococcus aureus.

- Duration: Typically 10 days, but can be individualized based on clinical response and pathogen.

- First-line combination: Ampicillin (150-200 mg/kg/day in divided doses IV) plus Gentamycin (5-6 mg/kg/day IV).

- For Older Children 2 months to 5 years (Hospitalized with Severe Pneumonia):

- First-line: Ceftriaxone (IV, 50-100 mg/kg/day once daily) or Ampicillin plus Gentamycin.

- Rationale: Ceftriaxone provides broad-spectrum coverage against Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae. Ampicillin + Gentamycin is an alternative.

- Consideration for Atypical Pathogens (e.g., Mycoplasma): If atypical pneumonia is suspected (e.g., persistent cough, gradual onset, older child), a macrolide (e.g., Azithromycin) may be added or used alone depending on clinical suspicion and local guidelines.

- Duration: Typically 7-10 days.

- First-line: Ceftriaxone (IV, 50-100 mg/kg/day once daily) or Ampicillin plus Gentamycin.

- For Children with Non-Serious Pneumonia (Outpatient Management):

- First-line: Amoxicillin (oral, 80-90 mg/kg/day divided twice daily).

- Rationale: Effective against Streptococcus pneumoniae, the most common bacterial cause in this age group, and has a good safety profile.

- Alternative if Amoxicillin Allergy or Suspected Atypical Pathogen: Macrolide (e.g., Azithromycin, Erythromycin) may be considered.

- Duration: Typically 5-7 days for uncomplicated cases.

- First-line: Amoxicillin (oral, 80-90 mg/kg/day divided twice daily).

- Fever Management:

- Paracetamol (Acetaminophen): Administer for fever (and pain) as per weight-based dosing.

- Tepid Sponging: Can be used as an adjunctive measure if the child is uncomfortable or has very high fever, but should not be the sole method of fever reduction and can cause discomfort.

- Goal: Improve comfort and reduce metabolic demands, not necessarily to normalize temperature.

- Respiratory Support:

- Positioning: Nurse patient in a semi-sitting up position or with the head elevated to aid breathing and improve lung expansion.

- Airway Clearance:

- Nasal Irrigation: With 0.9% sodium chloride to clear nasal passages, especially important in neonates and infants who are obligate nasal breathers.

- Assisted Coughing/Suctioning: If the child is unable to clear secretions effectively. Suctioning should be performed gently and only when necessary to avoid trauma or laryngospasm.

- Chest Physiotherapy (CPT) / Chest Exercises: Can be helpful, especially in cases with significant secretions or atelectasis, but evidence for routine use in uncomplicated pneumonia is mixed.

- Monitoring for Increased Respiratory Distress: Continuous assessment of respiratory rate, work of breathing, and oxygen saturation is paramount.

- Bronchodilators: Administer bronchodilators (e.g., inhaled salbutamol) if there is evidence of bronchospasm or significant wheezing, especially in children with a history of asthma or bronchiolitis.

- Oxygen Therapy:

- Indication: Administer oxygen where hypoxemia (SpO2 < 90-92% on room air) or cyanosis has occurred.

- Delivery Methods: Nasal cannula, oxygen mask, high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) for more severe cases.

- Goal: Maintain SpO2 > 90-92% (or higher, depending on clinical scenario).

- Fluid and Nutritional Support:

- Hydration: Promote adequate rehydration.

- Oral Fluids: Encourage frequent sips of oral fluids (water, breast milk, rehydration solutions) as tolerated.

- Intravenous (IV) Fluids: In children with severe respiratory difficulty, vomiting, or inability to take oral fluids, place an IV line and give fluids cautiously. Typically, start with 70-80% of normal maintenance fluids to avoid fluid overload, which can worsen pulmonary edema. Resume oral fluids as soon as possible.

- Nutrition:

- Breastfeeding on Demand: For infants, if they are able to suck effectively and without severe respiratory distress. Breast milk provides vital antibodies and nutrients.

- Well-Balanced Nutrition: For older children. If oral intake is poor due to dyspnea or fatigue, nasogastric tube (NGT) feeding may be necessary to ensure adequate caloric and fluid intake.

- Hydration: Promote adequate rehydration.

- Observations: Regular and frequent monitoring of respiratory rate, temperature, heart rate, and oxygen saturation is essential to assess response to treatment and detect deterioration.

- Hygiene: Maintain good personal and environmental hygiene to prevent further infections and transmission.

- Keep Patient Warm and Dry: Ensure comfortable body temperature and clean, dry clothing/bedding.

- Change Position: Regularly change the patient's position to prevent skin breakdown, promote lung expansion, and facilitate secretion drainage.

- Rest: Provide adequate rest periods to conserve the child's energy.

- Pain Management: Treat any associated pain (e.g., pleuritic chest pain) with analgesics like paracetamol or ibuprofen.

These diagnoses guide the nurse in identifying patient needs and planning individualized care.

- Ineffective Airway Clearance related to increased tracheobronchial secretions, ineffective cough (especially in young children), and inflammation, as evidenced by adventitious breath sounds (crackles, rhonchi), ineffective or absent cough, nasal flaring, tachypnea, dyspnea, pallor/cyanosis, poor feeding.

- Impaired Gas Exchange related to alveolar-capillary membrane changes (inflammation, exudate), ventilation-perfusion mismatch, as evidenced by tachypnea, dyspnea, hypoxemia (SpO2 < 90-92%), cyanosis, restlessness/irritability/lethargy, abnormal blood gases.

- Ineffective Breathing Pattern related to inflammation, pain (pleuritic), and fatigue, as evidenced by tachypnea, dyspnea, use of accessory muscles, shallow respirations, retractions, grunting.

- Risk for inadequate Fluid Volume related to fever, increased insensible fluid loss (tachypnea), decreased oral intake, and vomiting, as evidenced by dry mucous membranes, decreased urine output, poor skin turgor, sunken fontanelles (infants), absent tears.

- Inadequate protein energy intake related to anorexia, dyspnea, fatigue, increased metabolic needs, and difficult feeding, as evidenced by reported inadequate intake, weight loss/poor weight gain, refusal to eat/drink, fatigue during feeding.

- Hyperthermia related to infectious process and increased metabolic rate, as evidenced by elevated body temperature, flushed skin, tachycardia, tachypnea, irritability.

- Acute Pain related to inflammation of lung parenchyma/pleura or generalized body aches, as evidenced by verbal reports of pain (older child), grimacing, guarding, restlessness, crying, irritability, withdrawal.

- Activity Intolerance related to imbalance between oxygen supply and demand, generalized weakness, and fatigue, as evidenced by verbal reports of fatigue (older child), decreased play/activity, exertional dyspnea, abnormal heart rate/blood pressure response to activity.

- Excessive Anxiety (Child/Parent) related to dyspnea, threat to health status, hospitalization, unfamiliar environment, and fear of unknown outcomes, as evidenced by restlessness, crying, apprehension, irritability, verbalization of concerns.

- Inadequate Health Knowledge (Parents) related to disease process, treatment regimen, home care, and prevention, as evidenced by questions, inaccurate follow-through of instructions, verbalization of concerns.

These interventions are tailored to the child's age and developmental stage, focusing on gentle, non-threatening approaches.

| Intervention | Detail/Rationale |

|---|---|

| 1. Continuous Respiratory Assessment | Monitor respiratory rate, depth, rhythm, effort (retractions, nasal flaring, grunting), breath sounds, SpO2 (continuous pulse oximetry is often used), skin color (for cyanosis) every 1-4 hours or more frequently as needed. |

| 2. Positioning | Place the child in a semi-Fowler's position (head of bed elevated 30-45 degrees) or position of comfort to promote lung expansion. Avoid positions that might impede breathing. |

| 3. Airway Management |

|

| 4. Oxygen Therapy |

|

| 5. Administer Medications | Give bronchodilators, antibiotics, and other prescribed respiratory medications (e.g., corticosteroids) on time and monitor for effectiveness and side effects. |

| 6. Maintain Hydration | Ensure adequate hydration to thin secretions. (See Fluid and Nutrition section). |

| Intervention | Detail/Rationale |

|---|---|

| 1. Monitor Fluid Balance | Strictly monitor intake (oral, IV, NGT) and output (urine, stools, emesis). Assess for signs of dehydration (e.g., dry mucous membranes, sunken fontanelles, poor skin turgor, decreased urine output). |

| 2. Promote Hydration |

|

| 3. Optimize Nutrition |

|

| Intervention | Detail/Rationale |

|---|---|

| 1. Monitor Temperature | Assess temperature regularly. |

| 2. Fever Management |

|

| 3. Pain Assessment | Use age-appropriate pain scales (e.g., FLACC scale for non-verbal children, Faces Pain Scale for older children). |

| 4. Pain Management |

|

| Intervention | Detail/Rationale |

|---|---|

| 1. Balance Rest and Activity | Organize care to allow for uninterrupted rest periods. |

| 2. Encourage Age-Appropriate Activity | Gradually increase activity as tolerated, monitoring for signs of fatigue or respiratory distress. |

| 3. Assist with ADLs | Provide assistance with activities of daily living as needed to conserve energy. |

| Intervention | Detail/Rationale |

|---|---|

| 1. Child |

|

| 2. Parents |

|

| Intervention | Detail/Rationale |

|---|---|

| 1. Assess Learning Needs | Determine what parents already know and what information they need. |

| 2. Educate on |

|

| 3. Teach-Back Method | Have parents demonstrate or verbalize understanding of key information. |

| 4. Provide Written Materials | For reinforcement. |

Effective prevention can significantly reduce the global burden of this disease.

Vaccines are one of the most effective tools in preventing severe pneumonia and its complications in children.

- Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine (PCV):

- Targets: Streptococcus pneumoniae, the leading bacterial cause of pneumonia, meningitis, and sepsis in children.

- Impact: Dramatically reduced the incidence of invasive pneumococcal disease and pneumonia in vaccinated children and, through herd immunity, in unvaccinated individuals.

- Recommendation: Universal vaccination for infants, typically administered in a series of doses (e.g., PCV13, PCV15, PCV20 depending on national guidelines).

- Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) Vaccine:

- Targets: Haemophilus influenzae type b, another significant bacterial cause of pneumonia, meningitis, and epiglottitis.

- Impact: Led to a near elimination of invasive Hib disease in vaccinated populations.

- Recommendation: Universal vaccination for infants, typically administered in a series of doses.

- Influenza (Flu) Vaccine:

- Targets: Seasonal influenza viruses (Type A and B), which can directly cause viral pneumonia or predispose to secondary bacterial pneumonia.

- Impact: Reduces the risk of influenza illness, hospitalizations, and deaths.

- Recommendation: Annual vaccination for all children 6 months of age and older, especially those with underlying chronic conditions.

- Measles, Mumps, Rubella (MMR) Vaccine:

- Targets: Measles virus, which can cause severe pneumonia directly and also predispose to secondary bacterial pneumonia due to its immunosuppressive effects.

- Impact: Significantly reduced measles-associated pneumonia and mortality.

- Recommendation: Universal vaccination for children.

- Pertussis (Whooping Cough) Vaccine (DTaP/Tdap):

- Targets: Bordetella pertussis, which can cause severe pneumonia, especially in unvaccinated infants.

- Impact: Reduces the incidence and severity of pertussis.

- Recommendation: Universal vaccination for infants and booster doses for older children/adolescents. Tdap is also recommended for pregnant women to provide passive immunity to newborns.

- Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) Immunization (Passive):

- Targets: RSV, the leading cause of bronchiolitis and pneumonia in infants.

- Palivizumab (Synagis): A monoclonal antibody given monthly during RSV season to high-risk infants (e.g., premature infants, those with chronic lung disease, significant congenital heart disease).

- Newer options: Maternal RSV vaccine and longer-acting monoclonal antibodies are emerging.

- Impact: Reduces the severity and hospitalization rates due to RSV in vulnerable infants.

Malnutrition significantly impairs the immune system, making children more susceptible to infections, including pneumonia, and increasing the severity of illness.

- Exclusive Breastfeeding: For the first 6 months of life, breast milk provides essential antibodies and immune factors that protect infants from respiratory infections.

- Appropriate Complementary Feeding: After 6 months, introduce nutritious, age-appropriate complementary foods alongside continued breastfeeding up to 2 years and beyond.

- Adequate Overall Nutrition: Ensure children receive a balanced diet rich in vitamins and minerals to support a robust immune system. Addressing micronutrient deficiencies (e.g., Vitamin A, Zinc) can also be important.

Reducing exposure to pathogens and irritants is critical for preventing pneumonia.

- Improved Indoor Air Quality:

- Reduce Exposure to Indoor Air Pollution: Promote the use of clean cooking fuels and improved cooking stoves to reduce exposure to biomass fuel smoke.

- Avoid Tobacco Smoke Exposure: Strict avoidance of passive (secondhand) smoke exposure from parents/caregivers, as it irritates airways, impairs ciliary function, and increases susceptibility to respiratory infections.

- Good Hand Hygiene:

- Frequent Handwashing: Educate children and caregivers on the importance of frequent and thorough handwashing with soap and water, especially after coughing/sneezing, before eating, and after using the toilet.

- Reduce Crowding: Minimizing overcrowding, especially in daycare settings or households, can reduce the transmission of respiratory pathogens.

- Clean Water and Sanitation: Access to clean water and adequate sanitation can indirectly prevent infections that weaken the immune system.

- Early Recognition and Treatment of Illnesses: Promptly seek medical attention for respiratory symptoms to prevent progression to severe pneumonia.

- Management of Underlying Conditions: Effectively manage chronic conditions like asthma, cystic fibrosis, and congenital heart disease, which predispose children to pneumonia.

- HIV Prevention and Treatment: In regions with high HIV prevalence, preventing mother-to-child transmission and ensuring access to antiretroviral therapy for children with HIV are crucial, as HIV-positive children are at much higher risk of severe and recurrent pneumonia.

- Community Health Programs: Implement and support community-based health programs that promote child health, provide education, and improve access to primary healthcare services, especially in underserved areas.

- Antibiotic Stewardship: While a treatment strategy, responsible antibiotic use also plays a role in prevention by limiting the development of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, which could make future pneumonia harder to treat.

Very precise thanks

Thanks

I love it

Thanks for providing organized and knowledgeable note

Thanks

The mgt is very precise hope there is nothing left out,,any way thanks alot

very precise

Thanks a bunch 😊