Liver Cirrhosis

LIVER CIRRHOSIS

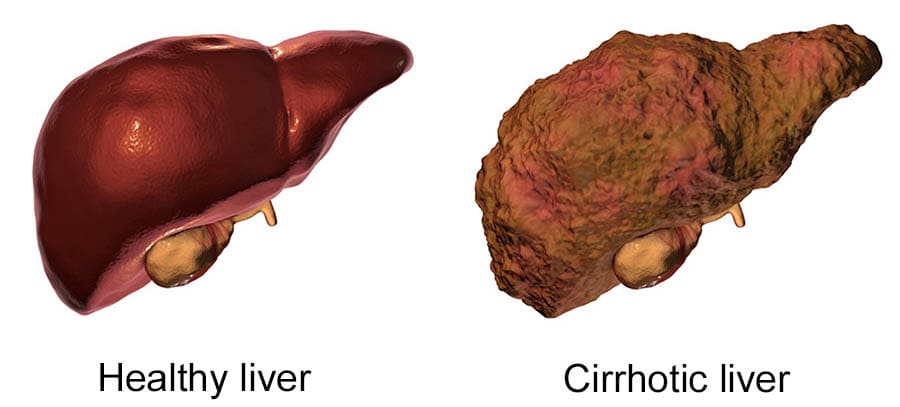

Cirrhosis is a chronic, irreversible disease characterized by the replacement of normal liver tissue with diffuse fibrosis (scar tissue). This scarring disrupts the normal structure and function of the liver, leading to necrosis of liver cells, nodule formation, and distortion of the liver's vascular network.

Types of Liver Cirrhosis

- Alcoholic Cirrhosis (Laennec's Cirrhosis): The most common type, resulting from chronic alcohol ingestion and associated malnutrition. The scar tissue characteristically surrounds the portal areas.

- Post-necrotic Cirrhosis: Characterized by broad bands of scar tissue, this type is often a late result of a previous acute viral hepatitis infection (especially Hepatitis B and C).

- Biliary Cirrhosis: Scarring occurs around the bile ducts due to chronic biliary obstruction and infection (cholangitis). It is much less common.

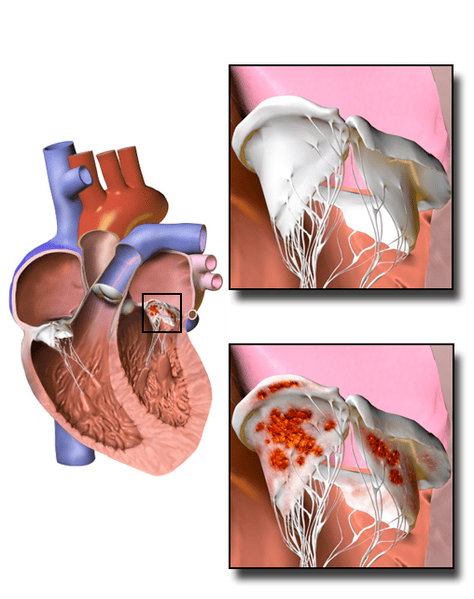

- Cardiac Cirrhosis: Results from long-standing, severe, right-sided heart failure, which causes chronic congestion and damage to the liver.

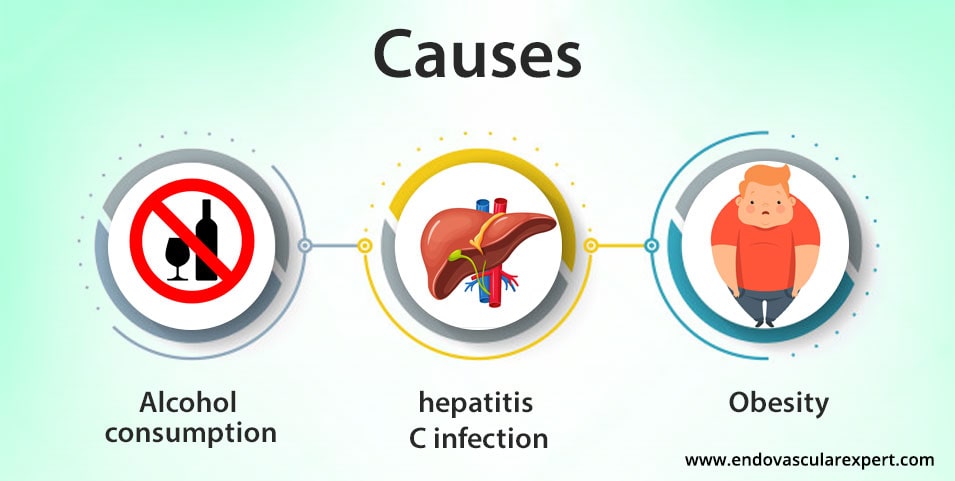

Causes of Liver Cirrhosis

- Infections: Chronic viral hepatitis B and C are major causes.

- Intoxication: Chronic, excessive alcohol consumption is the leading cause. Other toxins and drugs (e.g., methotrexate, isoniazid) can also cause cirrhosis.

- Metabolic and Infiltrative Disorders: Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), Wilson's disease (copper overload), and hemochromatosis (iron overload).

- Biliary Obstruction: Chronic congestion with bile (e.g., primary biliary cirrhosis - PBC).

- Vascular Congestion: Chronic congestion with blood (e.g., Budd-Chiari syndrome, cardiac failure).

- Idiopathic: In some cases, the cause is unknown.

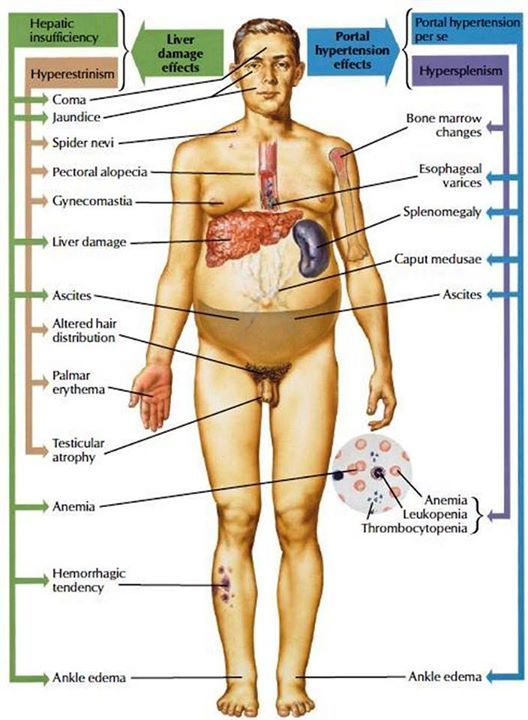

Clinical Features of Liver Cirrhosis

Signs and symptoms increase in severity as the disease progresses. Cirrhosis is often categorized as compensated or decompensated.

Compensated Cirrhosis

In this early stage, the liver is still able to perform most of its functions. Symptoms are often vague and may be discovered incidentally.

- Intermittent mild fever.

- Vascular spiders (spider angiomas) on the skin.

- Palmar erythema (reddened palms).

- Unexplained epistaxis (nosebleeds).

- Ankle edema.

- Vague morning indigestion and flatulent dyspepsia.

- Abdominal pain.

- A firm, enlarged liver (hepatomegaly) and splenomegaly.

Decompensated Cirrhosis

This is the late stage, where the liver is failing and signs of portal hypertension and liver insufficiency are prominent.

- Ascites: Accumulation of fluid in the peritoneal cavity.

- Jaundice: Yellowing of the skin and eyes.

- Weakness and Muscle Wasting.

- Weight Loss.

- Endocrine Changes:

- Loss of libido, testicular atrophy, gynecomastia (in males).

- Amenorrhea, irregular menses, breast atrophy (in females).

- Bleeding Tendencies: Spontaneous bruising, purpura (due to low platelet count), and epistaxis.

- Hepatic Encephalopathy: Confusion, altered mental state, and asterixis ("liver flap") due to the accumulation of ammonia.

- Other signs: Hair loss, finger clubbing, edema of the legs, and pain in the right upper abdominal quadrant.

Investigations for Liver Cirrhosis

- Liver Function Tests (LFTs): To assess liver functional abnormalities. Shows elevated liver enzymes (AST, ALT), alkaline phosphatase, and bilirubin. Serum albumin will be low.

- Complete Blood Count (CBC): To detect anemia and thrombocytopenia (low platelet count).

- Serological Tests: Blood tests to rule out viral hepatitis (B, C) and HIV.

- Coagulation Studies: Prothrombin Time (PT) will be prolonged due to decreased synthesis of clotting factors.

- Serum Electrolytes: To check for imbalances, especially hyponatremia.

- Abdominal Ultrasound: To reveal the size of the liver (can be enlarged or shrunken), assess for nodules, ascites, and other hepatic abnormalities.

- CT Scan: To assess for lobe enlargement, vascular changes, and nodules in more detail.

- Endoscopy (EGD): Crucial for identifying and assessing esophageal varices, a major complication of portal hypertension.

- Liver Biopsy: The definitive test to confirm the diagnosis by revealing the destruction and fibrosis of liver tissues.

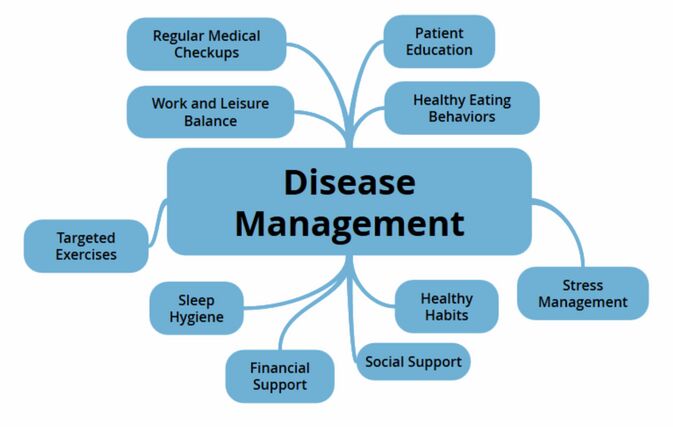

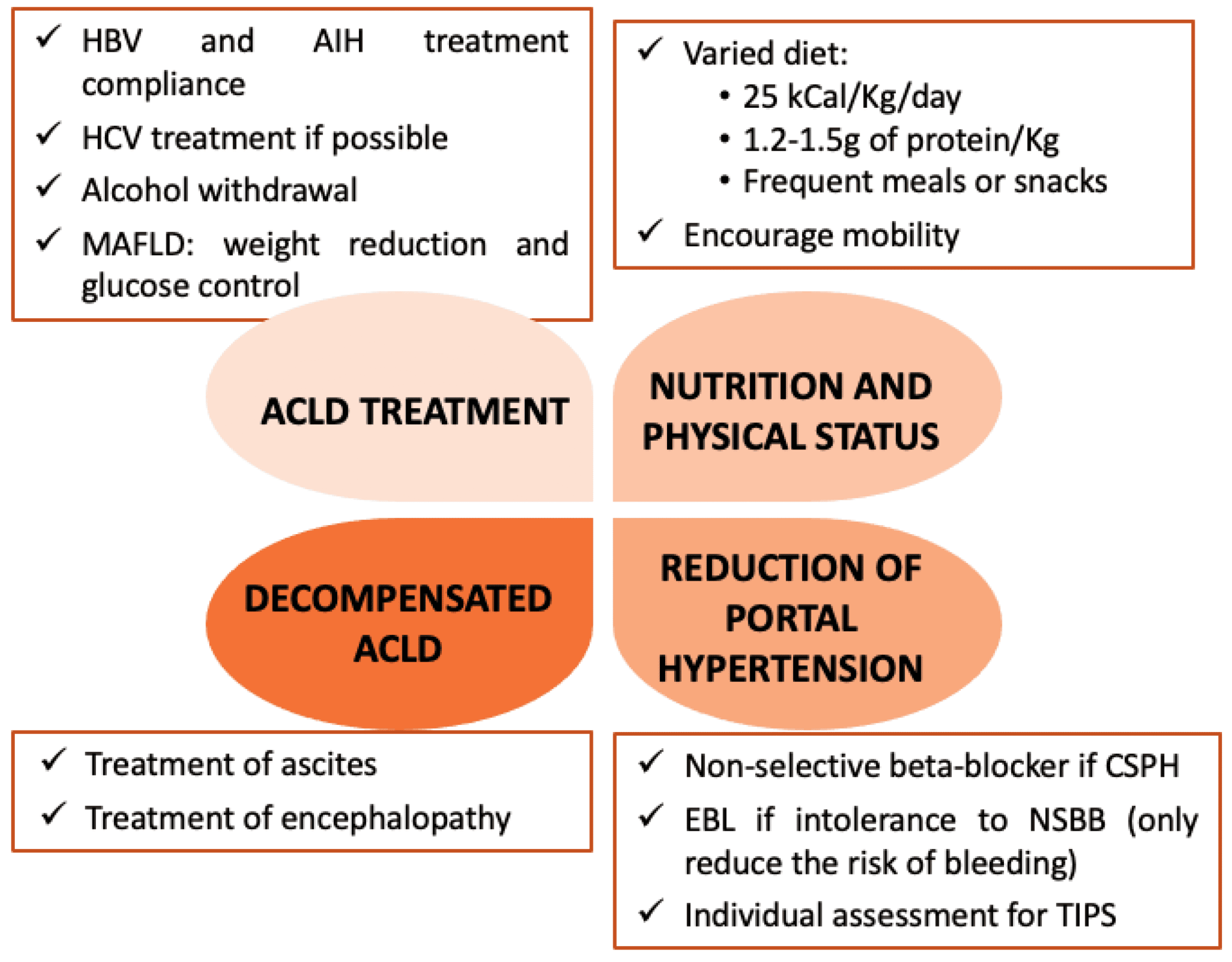

Management of a Patient with Liver Cirrhosis

Liver cirrhosis is a late-stage liver disease where healthy liver tissue is replaced by scar tissue, leading to irreversible liver damage and impaired liver function. Management is complex and aims to prevent further progression, manage complications, and improve the patient's quality of life.

Aims of Management

- To remove or alleviate the underlying cause of cirrhosis (e.g., abstinence from alcohol for alcoholic liver disease, antiviral therapy for chronic viral hepatitis).

- To prevent further liver damage and, where possible, promote regeneration of remaining healthy liver tissue.

- To prevent and effectively treat complications arising from portal hypertension and liver dysfunction (e.g., ascites, variceal bleeding, hepatic encephalopathy, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis).

- To improve the patient's quality of life and functional status.

Nursing Care Plan for Patients with Liver Cirrhosis

Nursing care is pivotal in managing symptoms, preventing complications, educating patients and families, and providing comprehensive supportive care.

1. Admission and Initial Assessment

- Establish Therapeutic Rapport: Build trust and rapport with the patient and family.

- Provide Counseling and Reassurance: Explain the condition, the management plan, and the importance of adherence to treatment in clear, understandable terms. Address anxieties and fears openly and empathetically. Encourage questions.

2. Ongoing Monitoring and Observations

- Monitor temperature, pulse, respiration, blood pressure, and oxygen saturation regularly (e.g., hourly, 2-hourly, or as ordered based on the patient's condition).

- Maintain an accurate observation chart.

- Report any abnormalities immediately (e.g., hypotension, tachycardia, fever, tachypnea), as these could indicate complications like bleeding, infection, or worsening liver failure.

- Skin: Jaundice (assess sclera, skin), severe pruritus, and skin integrity (assess for excoriations, pressure areas, edema, spider angiomas, palmar erythema).

- Bleeding: Signs of internal or external bleeding (epistaxis, hematemesis, melena, hematochezia, petechiae, purpura, easy bruising, bleeding gums).

- Neurological Status: Assess for signs of hepatic encephalopathy – confusion, disorientation, lethargy, slurred speech, asterixis (flapping tremors), changes in sleep-wake cycle, and ultimately coma. Use a grading scale (e.g., West Haven Criteria) if appropriate.

- Abdominal Assessment: Abdominal girth measurements (daily, at the same level) and assessment for fluid wave to quantify ascites. Note any tenderness or guarding.

- Edema: Peripheral edema (pitting vs. non-pitting, location, severity).

- Gastrointestinal: Nausea, vomiting, indigestion, abdominal discomfort, changes in bowel habits.

- Symptom Intensity: Note the intensity of all symptoms and report significant changes to the medical team.

3. Diagnostic Investigations

- Complete Blood Count (CBC): To check for anemia (due to chronic bleeding, malnutrition, or hemolysis), leukopenia, and thrombocytopenia (due to hypersplenism).

- Liver Function Tests (LFTs): Bilirubin (total and direct), AST, ALT, ALP, GGT to monitor liver synthetic and excretory function.

- Coagulation Profile: Prothrombin Time (PT), International Normalized Ratio (INR), Partial Thromboplastin Time (PTT) to assess clotting ability (impaired in liver dysfunction).

- Kidney Function Tests: Urea, Creatinine, Electrolytes to monitor renal function, especially with diuretics or potential hepatorenal syndrome.

- Serum Albumin: To assess liver synthetic function and risk of ascites/edema.

- Serum Ammonia: To monitor for hepatic encephalopathy.

- Serology: Blood tests for Hepatitis B (HBsAg, anti-HBc, HBeAg), Hepatitis C (anti-HCV, HCV RNA), Hepatitis D, and HIV to identify viral causes. Autoimmune markers if suspected.

- Imaging Studies:

- Abdominal Ultrasound: To assess liver size, texture, presence of ascites, portal vein patency, and rule out hepatocellular carcinoma.

- CT Scan/MRI: Provides more detailed imaging of the liver and associated structures.

- Liver Biopsy: The gold standard for confirming the diagnosis of cirrhosis, assessing its severity, and sometimes identifying the specific etiology (though often not required if clinical and imaging evidence is conclusive).

- Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD): To screen for and manage esophageal varices.

4. Pharmacological Management

- Diuretics: For ascites and edema. Spironolactone (a potassium-sparing diuretic) is often the first-line and is frequently combined with Furosemide (a loop diuretic) for synergistic effects. Monitor fluid balance and electrolytes carefully.

- Antiviral Treatment: For chronic Hepatitis B or C to manage the underlying cause and prevent disease progression.

- Lactulose: To reduce ammonia levels in patients with hepatic encephalopathy. It works as a laxative, promoting ammonia excretion in stool, and acidifies the colon, trapping ammonia.

- Rifaximin: A non-absorbable antibiotic sometimes used in conjunction with lactulose to reduce ammonia-producing bacteria in the gut.

- Vitamin Supplements:

- Vitamin B complex (especially thiamine, folate, B12) for nutritional deficiencies and to prevent Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome in alcoholic cirrhosis.

- Vitamin K: May be given to correct clotting abnormalities due to impaired synthesis of clotting factors.

- Fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E) if cholestasis is significant.

- Beta-blockers (e.g., Propranolol, Carvedilol): To reduce portal pressure and prevent variceal bleeding.

- Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs) or H2 Blockers: To decrease gastric acid secretion and prevent stress ulcers.

- Antibiotics: For infections (e.g., IV Ceftriaxone for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis).

- Albumin: Intravenous albumin infusions may be given during large-volume paracentesis or for severe hypoalbuminemia.

- Analgesics: Administer pain relief as prescribed (e.g., Tramadol). Avoid hepatotoxic drugs, especially NSAIDs and high doses of paracetamol, which can exacerbate liver damage or increase bleeding risk.

- Antiemetics: (e.g., Metoclopramide) for nausea and vomiting.

5. Non-Pharmacological Management & Lifestyle Modifications

- Provide a well-balanced diet adequate in calories and protein to promote liver regeneration and prevent malnutrition.

- Protein Moderation/Restriction: While protein is essential, it must be restricted only if the patient shows signs of hepatic encephalopathy (as protein breakdown produces ammonia). Otherwise, adequate protein intake is encouraged.

- Sodium Restriction: A strict low-sodium diet (< 2g/day) is essential to help manage and prevent ascites and peripheral edema.

6. Surgical Treatment and Procedures

7. Elimination Management

8. Hygiene and Skin Care

- Inspect skin daily for signs of breakdown, excoriations, or infection.

- Use mild soaps and moisturizers.

- Implement 4-hourly repositioning and use pressure-relieving devices (e.g., special mattresses, cushions) to prevent pressure sores.

- Manage pruritus effectively (see symptom management above).

9. Activity and Mobility

10. Discharge Planning and Education

When the patient's condition has stabilized and they are deemed fit for discharge, provide comprehensive education to the patient and their family to ensure continuity of care and prevent readmission:

Complications of Liver Cirrhosis

The major complications of liver cirrhosis primarily stem from two pathological processes: portal hypertension and progressive liver cell failure. These complications are often life-threatening and require prompt and aggressive management.

- Portal Hypertension: This is a key complication resulting from increased resistance to blood flow through the cirrhotic liver. The scar tissue obstructs the normal flow of blood from the portal vein (which collects blood from the GI tract and spleen) into the hepatic veins. This leads to an increase in blood pressure within the portal venous system, which then causes a cascade of other complications.

- Variceal Hemorrhage: Due to portal hypertension, blood is shunted into collateral vessels, particularly in the esophagus and stomach (esophageal and gastric varices). These vessels are thin-walled, fragile, and not designed for high pressure. They are prone to rupture, leading to life-threatening gastrointestinal bleeding. Bleeding can be triggered by muscular exertion (e.g., straining during defecation, severe coughing), irritation from food, or gastric reflux. This is a medical emergency.

- Ascites: The accumulation of large amounts of fluid in the peritoneal (abdominal) cavity. It is caused by a combination of high pressure in the portal system (forcing fluid out of vessels), low levels of serum albumin (due to impaired liver synthesis, reducing oncotic pressure and leading to fluid leakage from vessels), and renal retention of sodium and water.

- Hepatic Encephalopathy: A complex, reversible neuropsychiatric syndrome resulting from the accumulation of toxic substances in the blood, primarily ammonia, which the damaged liver can no longer effectively detoxify. These toxins bypass the liver via shunts and reach the brain, leading to altered mental status, confusion, disorientation, changes in personality, asterixis (flapping tremors), and can progress to stupor and coma. Precipitating factors include GI bleeding, infection, constipation, high protein intake, and electrolyte imbalances.

- Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis (SBP): A severe infection of the ascitic fluid that occurs in the absence of an obvious source of infection. It is a common and life-threatening complication in patients with ascites, believed to occur due to bacterial translocation from the gut into the ascitic fluid. Signs include fever, abdominal pain, and worsening encephalopathy.

- Hepatorenal Syndrome (HRS): A severe and often fatal complication characterized by progressive kidney failure in people with advanced liver disease, particularly cirrhosis. It is a functional renal failure, meaning there is no intrinsic kidney disease; rather, it results from severe vasoconstriction of renal arteries due to complex circulatory abnormalities in liver failure, leading to reduced blood flow to the kidneys.

- Hepatopulmonary Syndrome (HPS): A triad of liver disease, intrapulmonary vascular dilations, and arterial hypoxemia. It results from abnormal vasodilation of the pulmonary capillaries, leading to impaired gas exchange.

- Portopulmonary Hypertension: Pulmonary hypertension that develops in patients with portal hypertension, not directly related to HPS, but due to pulmonary arterial vasoconstriction.

- Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC): Cirrhosis, regardless of its cause, is the strongest risk factor for the development of primary liver cancer. Regular screening for HCC is crucial.

- Coagulopathy: Impaired synthesis of clotting factors by the diseased liver leads to increased bleeding tendencies.

- Malnutrition and Muscle Wasting: Common due to anorexia, malabsorption, and altered metabolism.

- Infections: Patients with cirrhosis are immunocompromised and highly susceptible to various infections (e.g., pneumonia, UTIs, skin infections, SBP).

Nursing Diagnoses and Interventions for Liver Cirrhosis

Below are common nursing diagnoses for patients with liver cirrhosis, along with their associated nursing interventions.

1. Excess Fluid Volume

- Monitor Fluid Balance: Accurately measure and record daily weight, strict intake and output.

- Assess Edema and Ascites: Measure abdominal girth daily at the same level. Assess for peripheral and sacral edema (pitting vs. non-pitting).

- Administer Diuretics: Give prescribed diuretics (e.g., Spironolactone, Furosemide) and monitor their effectiveness.

- Monitor Electrolytes: Closely monitor serum sodium, potassium, and creatinine levels, reporting abnormalities.

- Restrict Sodium: Implement and educate patient/family on a strict low-sodium diet as ordered.

- Fluid Restriction: Implement fluid restriction only if ordered and necessary (e.g., severe dilutional hyponatremia).

- Positioning: Elevate edematous extremities. Elevate the head of the bed (semi-Fowler's) to improve breathing if ascites is causing dyspnea.

- Skin Care: Provide meticulous skin care to edematous areas to prevent breakdown.

- Patient Education: Educate on rationale for sodium/fluid restriction, medication regimen, and reporting increased swelling or weight gain.

2. Inadquate protein energy intake

- Assess Nutritional Status: Monitor weight, evaluate dietary intake, assess for signs of malnutrition (muscle wasting, skin turgor).

- Provide Nutritional Support: Collaborate with a dietitian to develop an individualized meal plan.

- Offer Small, Frequent Meals: To improve tolerance and increase overall intake.

- Encourage Calorie-Dense Foods: Unless contraindicated.

- Protein Management: Provide adequate protein unless signs of hepatic encephalopathy are present. If encephalopathy, moderate protein intake as directed.

- Administer Vitamin Supplements: As prescribed (e.g., B vitamins, fat-soluble vitamins, Vitamin K).

- Manage Nausea: Administer antiemetics before meals as prescribed.

- Oral Hygiene: Provide meticulous oral care before meals to enhance appetite.

- Create Pleasant Environment: Ensure a comfortable and appealing environment for meals.

- Patient Education: Educate on dietary modifications, avoidance of alcohol, and importance of nutrition.

3. Risk for Bleeding

- Monitor for Bleeding: Routinely assess for signs of bleeding (check stool for melena, emesis for coffee grounds/bright blood, urine for hematuria, skin for petechiae/ecchymosis).

- Monitor Coagulation Profile: Review PT/INR, PTT, and platelet count.

- Administer Vitamin K: As prescribed to improve clotting factor synthesis.

- Avoid Trauma: Use soft toothbrushes, electric razors. Avoid IM injections if possible; if given, use smallest gauge needle and apply prolonged pressure.

- Prevent Constipation/Straining: Encourage high-fiber diet, fluids, and administer stool softeners/laxatives (like lactulose) to prevent straining, which can increase variceal pressure.

- Administer Medications to Reduce Portal Pressure: Beta-blockers as prescribed.

- Prepare for Endoscopic Procedures: If varices are known, prepare patient for EGD and band ligation/sclerotherapy.

- Emergency Preparedness: Have emergency equipment (e.g., Sengstaken-Blakemore tube, IV access) readily available if variceal hemorrhage is suspected.

- Patient Education: Educate on bleeding precautions, signs of bleeding to report, and medication adherence.

4. Altered Thought Processes / Risk for Acute Confusion

- Assess Neurological Status: Perform frequent neurological assessments, including LOC, orientation, presence of asterixis, and appropriateness of behavior/speech. Use a standardized scale if applicable.

- Monitor Ammonia Levels: Review serum ammonia levels.

- Administer Medications: Give lactulose as prescribed to reduce ammonia (monitor for desired number of soft stools per day). Administer rifaximin if ordered.

- Protein Restriction: If severe encephalopathy, ensure adherence to prescribed protein restriction (usually temporary).

- Ensure Bowel Regularity: Encourage regular bowel movements to excrete ammonia.

- Safety Precautions: Implement fall precautions (side rails up, bed in low position, assist with ambulation). Supervise activities.

- Maintain Calm Environment: Minimize sensory overload. Provide reorientation as needed (calendar, clock).

- Communicate Clearly: Use simple, direct commands. Allow time for response.

- Family Education: Educate family on signs of encephalopathy and rationale for treatment.

5. Impaired Skin Integrity / Risk for Impaired Skin Integrity

- Assess Skin Daily: Inspect skin for signs of breakdown, dryness, excoriations, color changes, and bruising.

- Pressure Area Care: Turn patient every 2 hours or use pressure-relieving devices (e.g., air mattress, foam cushions).

- Moisturize Skin: Apply emollients and lotions to dry skin.

- Manage Pruritus: Administer anti-itch medications (e.g., cholestyramine, antihistamines) as prescribed. Keep nails short, suggest wearing soft cotton clothing. Provide cool baths.

- Gentle Skin Care: Use mild soaps and avoid harsh scrubbing. Pat skin dry gently.

- Nutrition: Promote good nutrition to support skin healing and integrity.

- Protect from Injury: Pad side rails if patient is agitated or confused.

6. Risk for Infection

- Monitor for Signs of Infection: Monitor temperature, WBC count. Assess for new onset or worsening abdominal pain, fever, or changes in mental status (suggesting SBP).

- Aseptic Technique: Use strict aseptic technique for all invasive procedures (IV insertion, paracentesis, Foley catheterization).

- Promote Pulmonary Hygiene: Encourage deep breathing and coughing to prevent pneumonia.

- Administer Antibiotics: As prescribed for diagnosed infections (e.g., SBP prophylaxis or treatment).

- Good Hand Hygiene: Educate patient, family, and staff on proper hand hygiene.

- Avoid Crowds: Advise patient to avoid large crowds and sick individuals.

- Vaccinations: Educate on importance of influenza and pneumococcal vaccines.

7. Activity Intolerance

- Assess Activity Level: Determine current activity tolerance and level of fatigue.

- Promote Rest: Provide undisturbed periods of rest. Organize care to allow for rest.

- Gradual Increase in Activity: Encourage progressive activity as tolerated. Collaborate with physical therapy for mobility plan.

- Assist with ADLs: Provide assistance with self-care activities as needed to conserve energy.

- Positioning: Elevate head of bed to ease breathing during activity.

- Nutrition: Promote optimal nutrition to improve energy levels.

- Patient Education: Educate on energy conservation techniques and importance of balancing rest and activity.