Gynaecology Full Revision Papers

Gynecology Question for Revision - Topic 1

This section covers congenital/acquired anomalies, uterine fibroids, and uterine prolapse.

SECTION A: Multiple Choice Questions (40 Marks)

1. Which of the following is a congenital abnormality of the female genital tract?

2. Imperforate hymen is classified as a:

3. Which of the following is NOT a complication of uterine fibroids?

4. Uterine prolapse is most commonly due to:

5. A transverse vaginal septum results from:

6. Which imaging technique is most useful for diagnosing uterine anomalies?

7. Mullerian agenesis results in:

8. Uterine fibroids are also known as:

9. Which condition is characterized by uterus divided into two horns?

10. A major symptom of vaginal atresia is:

SECTION B: Fill in the Blanks (10 Marks)

1. A ________ uterus is one where the uterine cavity is divided by a fibrous or muscular septum.

2. The absence of menstruation due to congenital absence of the uterus is called ________.

3. The congenital anomaly characterized by one uterine horn is known as ________ uterus.

4. The instrument used to visualize the inside of the uterus is called a ________.

5. ________ is the protrusion of the uterus through the vaginal canal.

6. A complete fusion failure of the Mullerian ducts results in a ________ uterus.

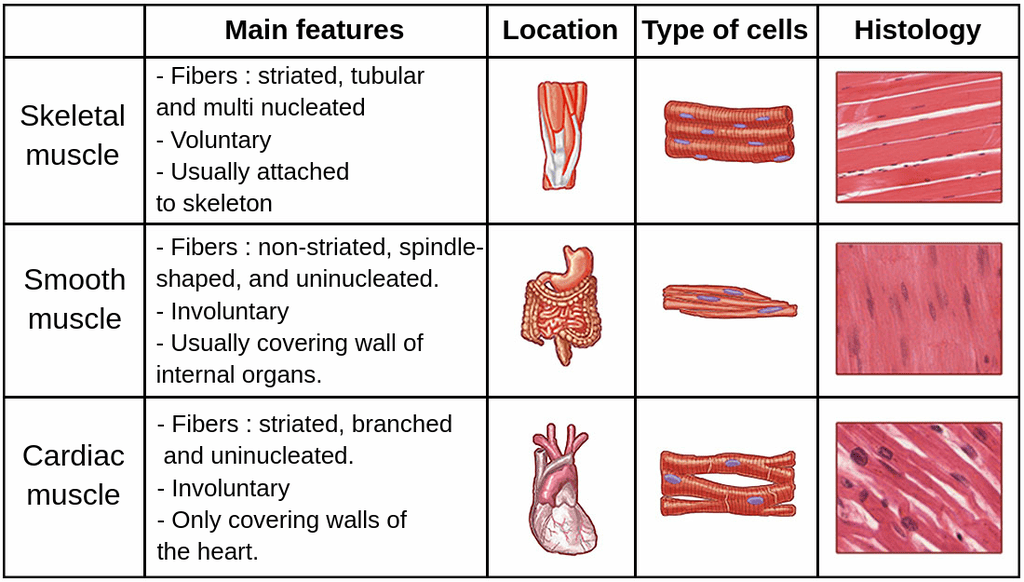

7. ________ is a benign tumor made of smooth muscle cells in the uterus.

8. A ________ is a transverse membrane within the vaginal canal, which may obstruct menstrual flow.

9. Vaginal agenesis is commonly associated with ________ syndrome.

10. ________ imaging is the first-line modality in evaluating uterine anomalies.

SECTION C: Short Essay Questions (10 Marks)

1. Define uterine fibroids and mention two symptoms.

Definition:

- Uterine fibroids, also called leiomyomas or myomas, are non-cancerous (benign) growths.

- They develop from the smooth muscle tissue in the wall of the uterus.

- They can vary in size from very small to quite large and can grow inside the uterine wall, just under the lining, or on the outer surface.

Two symptoms:

- Heavy Menstrual Bleeding (Menorrhagia): Periods that are much heavier or last much longer than usual, sometimes leading to anemia.

- Pelvic Pain or Pressure: A feeling of fullness, heaviness, or aching in the lower abdomen or pelvis, or pain during periods or sexual intercourse.

2. Explain the difference between bicornuate and septate uterus.

Bicornuate Uterus:

- This happens due to *incomplete fusion* of the Mullerian ducts.

- The uterus is shaped like a heart, with two distinct "horns" at the top, often seen externally.

- There may be a partial division *inside* the cavity, but the main problem is the external shape.

Septate Uterus:

- This happens due to *incomplete resorption* of the wall (septum) after the Mullerian ducts have fused.

- The external shape of the uterus is usually normal.

- There is a fibromuscular wall (septum) *inside* the uterine cavity that divides it, which can extend partly or completely down to the cervix.

3. Outline three causes of uterine prolapse.

- Vaginal Childbirth: The process of pushing a baby through the birth canal can stretch and weaken the muscles and ligaments that support the uterus. The risk increases with multiple vaginal deliveries or difficult births.

- Aging and Menopause: As women get older, the pelvic floor muscles naturally lose some strength. After menopause, the decrease in estrogen levels can make the pelvic tissues thinner and weaker.

- Increased Abdominal Pressure: Activities or conditions that constantly strain the muscles of the abdomen and pelvis can push down on the pelvic organs. Examples include chronic coughing, long-term constipation with straining, and regularly lifting heavy objects.

4. List three congenital structural abnormalities of the vagina.

- Vaginal Agenesis: This is when the vagina is either completely absent or much shorter than normal from birth.

- Transverse Vaginal Septum: A horizontal wall of tissue located within the vagina that can block the canal, sometimes completely.

- Imperforate Hymen: The hymen, which is supposed to have an opening, completely covers the vaginal opening from birth.

5. Describe how imperforate hymen presents clinically.

An imperforate hymen typically becomes noticeable when a girl reaches puberty and is expected to start menstruating (around age 12-15). The main way it presents is:

- Primary Amenorrhea: She does not have her first menstrual period.

- Cyclic Pelvic Pain: She experiences monthly pain in her lower abdomen or pelvis, similar to menstrual cramps, because menstrual blood is being produced but cannot escape.

- Abdominal Swelling/Mass: Over time, the trapped menstrual blood can build up in the vagina (hematocolpos) and sometimes the uterus, causing the lower abdomen to swell or a mass to be felt during examination.

6. State three complications of uterine anomalies during pregnancy.

- Recurrent Pregnancy Loss (Miscarriage): Some uterine shapes, particularly a septate uterus, can make it difficult for a pregnancy to continue because the blood supply to the septum is poor, or the space is restricted, leading to repeated miscarriages.

- Preterm Birth: An abnormally shaped uterus might not expand properly as the baby grows, leading to the baby being born too early (before 37 weeks of pregnancy).

- Fetal Malposition: The irregular shape of the uterus can prevent the baby from turning into the head-down position for delivery, increasing the chances of needing a Cesarean section or leading to breech presentation.

7. What is the role of ultrasound in diagnosing female genital abnormalities?

Ultrasound is the primary imaging method used to check for abnormalities in the female reproductive organs because it is:

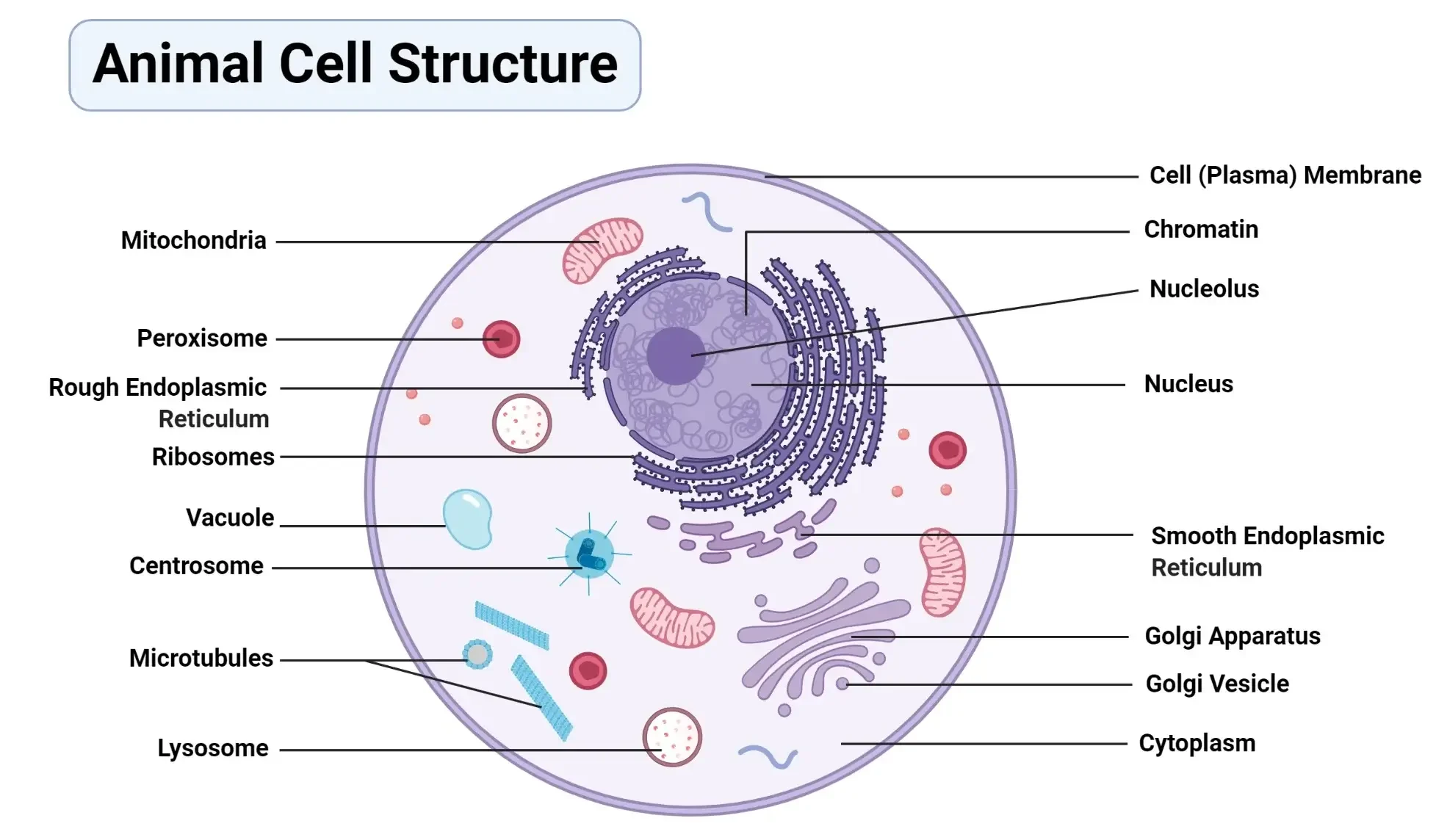

- Visualisation: It provides clear images of the uterus, ovaries, and often the vagina. Transvaginal ultrasound (where a probe is inserted into the vagina) gives the best views of the uterus and ovaries.

- Structure Assessment: It helps doctors see the size, shape, and internal structure of the uterus, which is crucial for identifying anomalies like septums, horns, or absence of the uterus. 3D ultrasound is particularly good for mapping the uterine cavity and external shape.

- Identifying Blockages: In cases like imperforate hymen or vaginal septum, ultrasound can show the buildup of menstrual blood behind the blockage.

- Initial Screening: It is often the first test done when a congenital anomaly or condition like fibroids is suspected because it is widely available, safe, and relatively inexpensive.

8. Differentiate between congenital and acquired genital abnormalities.

- Congenital Abnormalities:

- These are problems that are present from birth.

- They happen because the reproductive organs did not form or develop correctly while the baby was in the womb.

- Examples: Bicornuate uterus, septate uterus, vaginal agenesis, imperforate hymen.

- Acquired Abnormalities:

- These are problems that a person develops *after* birth, during their life.

- They are caused by factors like infections, injuries, surgeries, or changes related to age or hormones.

- Examples: Uterine fibroids, pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), uterine prolapse, vaginal fistulas.

9. Briefly describe the management of a uterine prolapse in a multiparous woman.

Management for uterine prolapse in a woman who has had multiple children depends on how severe the prolapse is and her symptoms:

- Conservative Management (Mild Prolapse): For slight dropping with minimal symptoms, management includes advising on weight loss if overweight, avoiding heavy lifting, and teaching pelvic floor exercises (Kegel exercises) to strengthen the supporting muscles.

- Pessaries (Moderate to Severe Prolapse): These are removable devices inserted into the vagina to hold the uterus in place. They are a good option if the woman does not want surgery or has other health issues that make surgery risky.

- Surgical Management (More Severe/Symptomatic Prolapse): If conservative methods fail or the prolapse is significant, surgery can be done. This might involve stitching the pelvic floor tissues to provide support, or removing the uterus (hysterectomy) along with repairing the vaginal support.

10. List three complications of untreated vaginal septum.

- Accumulation of Menstrual Blood (Hematocolpos): If a transverse septum completely blocks the vagina and there is a functioning uterus, menstrual blood will collect above the septum, leading to severe pain, a noticeable mass in the abdomen, and potentially affecting kidney function over time due to pressure.

- Painful Intercourse (Dyspareunia): A rigid or thick septum can make sexual activity difficult and painful.

- Complications during Childbirth: If a vaginal septum is not identified and removed before pregnancy, it can cause problems during labor by blocking the baby's passage through the birth canal, potentially requiring a Cesarean section.

SECTION D: Long Essay Questions (10 Marks Each)

1. Discuss the causes, signs and symptoms, diagnosis, and management of uterine fibroids.

Causes of Uterine Fibroids:

- Hormones: Estrogen and progesterone, the main female hormones, seem to fuel the growth of fibroids. Fibroids tend to grow during the reproductive years when hormone levels are high and shrink after menopause when levels drop.

- Genetics: Fibroids often run in families, suggesting a genetic link.

- Other Growth Factors: Substances in the body that help cells grow also seem to play a role in fibroid development.

- Origin: They start from a single muscle cell in the uterus that multiplies repeatedly.

Signs and Symptoms:

- Heavy or Prolonged Menstrual Bleeding (Menorrhagia): This is the most common symptom, leading to anemia in some women.

- Pelvic Pressure or Pain: Large fibroids can press on the bladder (causing frequent urination), rectum (causing constipation), or cause a feeling of heaviness or fullness in the lower abdomen. Pain may occur during periods or sexual intercourse.

- Enlarged Abdomen: Very large fibroids can make the abdomen look swollen, similar to pregnancy.

- Infertility or Pregnancy Problems: Fibroids, especially those inside the uterine cavity, can make it hard to get pregnant, cause miscarriages, or lead to preterm labor.

- Lower Back Ache: Fibroids pressing on nerves or muscles in the pelvis can cause back pain.

Diagnosis:

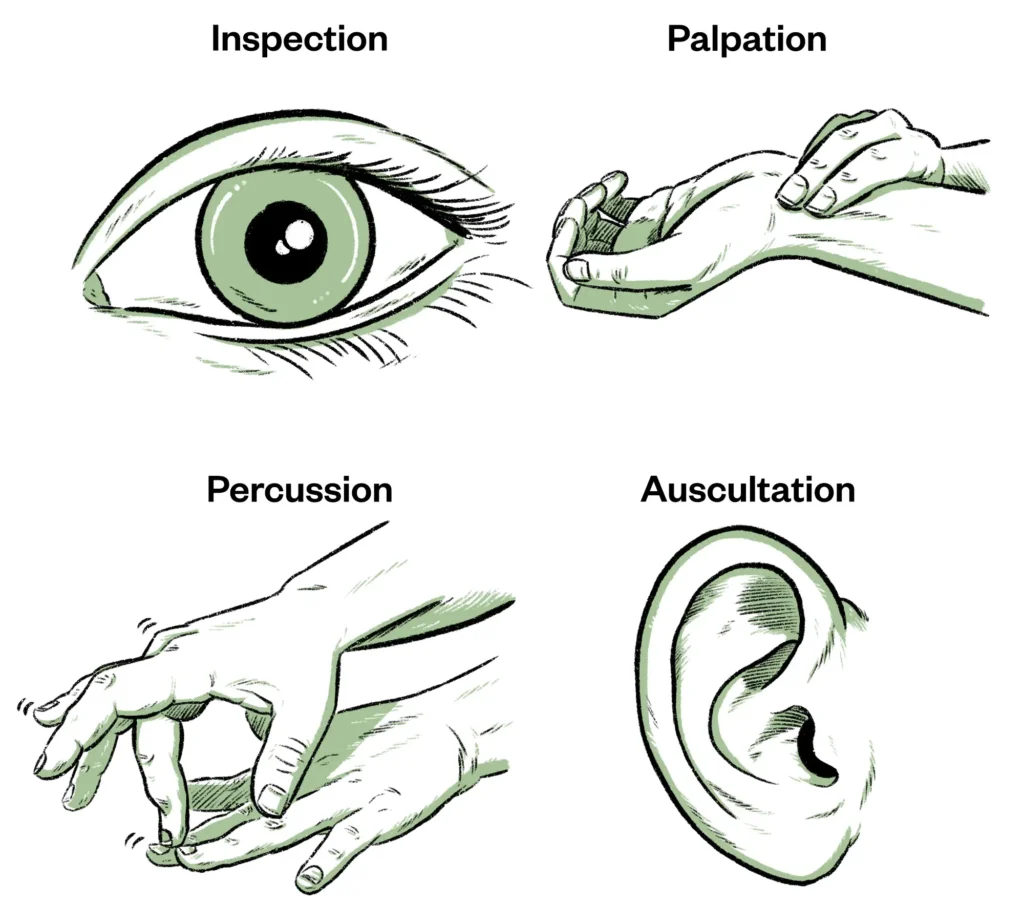

- Pelvic Examination: The doctor may feel an enlarged or irregularly shaped uterus during a routine exam.

- Ultrasound: This is the main tool for confirming fibroids, showing their size, location, and number. Transvaginal ultrasound gives better detail.

- MRI: Used for more complex cases, large fibroids, or when planning surgery, providing detailed images.

- Hysteroscopy: A small camera is inserted into the uterus to visualize fibroids growing inside the cavity.

- Laparoscopy: A minimally invasive surgical procedure where a camera is inserted through a small cut in the abdomen to view fibroids on the outside of the uterus.

Management:

- Watchful Waiting: For small, asymptomatic fibroids, no treatment is needed, and they are monitored over time.

- Medications:

- Pain relievers (like ibuprofen) for mild pain.

- Hormonal medications (like birth control pills, progesterone, GnRH agonists) to reduce bleeding and shrink fibroids temporarily by lowering estrogen levels.

- Non-Surgical Procedures:

- Uterine Artery Embolization (UAE): Blocking the blood vessels that supply the fibroids to shrink them.

- Focused Ultrasound Surgery (FUS): Using ultrasound waves to destroy fibroid tissue.

- Surgical Treatment:

- Myomectomy: Surgical removal of the fibroids while leaving the uterus intact, often chosen by women who want to have children in the future. Can be done through open surgery, laparoscopy, or hysteroscopy depending on fibroid location.

- Hysterectomy: Removal of the entire uterus. This is a permanent solution, usually chosen by women who have severe symptoms and do not plan to have more children.

2. Explain congenital malformations of the uterus, highlighting types, clinical features, and management.

What are Congenital Malformations of the Uterus?

- These are birth defects where the uterus doesn't form in the typical way while a female baby is developing in the womb.

- They happen due to problems with how the Mullerian ducts form and fuse together.

- These malformations can affect the shape, size, or presence of the uterus, fallopian tubes, cervix, and upper vagina.

Types of Uterine Anomalies:

- Septate Uterus: The most common type. A wall (septum) divides the inside of the uterus, usually impacting the uterine cavity shape more than the external shape.

- Bicornuate Uterus: The uterus has two distinct horns, often giving it a heart shape externally, due to partial fusion failure.

- Unicornuate Uterus: Only one side of the uterus develops fully, resulting in a smaller uterus with a single horn.

- Didelphys Uterus: Complete failure of fusion results in two separate uteri, each with its own cervix, and sometimes a double vagina.

- Arcuate Uterus: A mild indentation at the top of the uterine cavity; often considered a normal variant.

- Uterine Agenesis/Hypoplasia: Complete absence (agenesis) or underdevelopment (hypoplasia) of the uterus.

Clinical Features:

- Many women with uterine anomalies have no symptoms and may only discover the condition incidentally during imaging for other reasons.

- Reproductive Problems: The most common issues are difficulty getting pregnant (infertility), recurrent miscarriages, and preterm birth. Septate uterus is strongly linked to recurrent pregnancy loss.

- Menstrual Issues: Some anomalies, especially those with associated vaginal blockages (like a transverse septum in the vagina), can cause absence of menstruation (amenorrhea) with cyclic pain.

- Pelvic Pain: Less commonly, some anomalies might cause pelvic pain.

Management:

- Observation: If the anomaly is not causing symptoms or reproductive problems (like an arcuate uterus or some bicornuate uteri), no treatment may be needed.

- Surgical Correction: Surgery is typically offered when the anomaly is causing recurrent miscarriages or infertility.

- Hysteroscopic Septum Resection: Surgery done through the vagina using a camera to remove a uterine septum. This is a common procedure with good success rates for improving pregnancy outcomes in women with septate uteri and recurrent loss.

- Metroplasty: More complex surgeries to reconstruct the uterus (e.g., joining the two horns of a bicornuate uterus), less commonly performed now compared to septum resection.

- Vaginoplasty: Creating a vagina if it is absent or underdeveloped (as in vaginal agenesis).

- Counseling: Providing information and support regarding the potential impact on fertility and pregnancy.

3. Discuss the types, causes, and management of vaginal agenesis.

What is Vaginal Agenesis?

- Vaginal agenesis is a congenital condition where the vagina is absent or significantly shorter than normal.

- It often occurs as part of a syndrome called Mayer-von Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser (MRKH) syndrome, where the uterus is also typically absent or very underdeveloped, while the ovaries are usually normal.

- Isolated vaginal agenesis (vagina is absent, but uterus is present and functional) is less common but possible.

Causes:

- Vaginal agenesis is a birth defect resulting from problems during the early development of the reproductive system in the womb.

- It is primarily due to the failure of the Mullerian ducts to develop properly, which are supposed to form the uterus, fallopian tubes, cervix, and upper vagina.

- The exact reasons why this happens are often unclear, but it is sometimes associated with genetic factors.

Management:

- The main goal of management is to create a functional vagina for sexual intercourse if desired by the individual.

- Non-Surgical Dilation: This is often the first approach. It involves using a series of progressively larger dilators (smooth, rod-like instruments) to stretch the existing vaginal dimple or pouch over time, creating a functional vaginal canal. This requires commitment and consistency.

- Surgical Creation of a Vagina (Vaginoplasty): If dilation is unsuccessful or not suitable, surgery can be performed. Different surgical techniques exist, including using skin grafts, portions of the bowel, or other tissues to create a new vaginal canal.

- Timing of Intervention: Treatment is typically delayed until the individual is old enough to understand her condition, is emotionally mature, and desires to be sexually active.

- Psychological Support: Counseling is very important to help individuals and their families understand the condition and cope with the emotional and psychological impact, especially concerns about body image, identity, and relationships.

- Addressing Associated Anomalies: In MRKH syndrome, the ovaries are functional, so hormonal development and secondary sexual characteristics (like breast growth) occur. However, because the uterus is absent, pregnancy is not possible directly, though having genetic children via surrogacy is an option if ovaries are present. Other associated abnormalities, like kidney or skeletal problems, also need to be evaluated and managed.

4. Describe uterine prolapse under the following: causes, degrees, clinical features, and treatment options.

What is Uterine Prolapse?

- Uterine prolapse occurs when the uterus drops down into or out of the vagina.

- It happens because the pelvic floor muscles, ligaments, and connective tissues that support the uterus weaken and can no longer hold it in its normal position.

- It is a type of pelvic organ prolapse, which can also involve the bladder (cystocele), rectum (rectocele), or vagina itself.

Causes:

- Vaginal Childbirth: The most common cause. The stress and stretching of the pelvic floor during labor and delivery, especially with multiple births, large babies, or assisted deliveries (like forceps), can damage the support structures.

- Aging: As women age, muscles naturally lose tone and strength, including the pelvic floor muscles.

- Menopause: The decrease in estrogen after menopause causes tissues to become thinner and less elastic, weakening the pelvic support.

- Increased Abdominal Pressure: Chronic conditions that put pressure on the abdomen and pelvis, such as:

- Chronic cough (e.g., from smoking or asthma)

- Chronic constipation and straining during bowel movements

- Heavy lifting (occupation or exercise)

- Obesity

- Genetics: Some women may have a genetic predisposition to weaker connective tissues.

Degrees (Staging): The severity is classified based on how far the uterus has descended:

- Stage 1: The uterus drops into the upper part of the vagina.

- Stage 2: The uterus has dropped further and reaches the opening of the vagina.

- Stage 3: The cervix (the lower part of the uterus) is outside the vaginal opening.

- Stage 4: Most or all of the uterus is outside the vagina.

Clinical Features (Signs and Symptoms):

- Symptoms vary depending on the stage; mild prolapse may have no symptoms.

- Feeling of Heaviness or Pressure: A dragging sensation in the pelvis or lower abdomen.

- Vaginal Bulge: The sensation of a lump or "something falling out" in the vagina.

- Difficulty with Urination: Frequent urination, feeling of incomplete bladder emptying, or stress incontinence (leaking urine with cough, sneeze, or exercise). In severe cases, difficulty passing urine.

- Difficulty with Bowel Movements: Constipation or the need to press on the vagina to help empty the bowels (in cases of associated rectocele).

- Lower Back Pain: May be associated with the dragging sensation.

- Pain or Discomfort during Intercourse: Can be affected by the presence of prolapse.

Treatment Options:

- Conservative (Non-Surgical):

- Lifestyle Changes: Weight loss, managing constipation, avoiding heavy lifting, stopping smoking (to reduce cough).

- Pelvic Floor Exercises (Kegels): Strengthening the muscles to improve support. Most effective for mild prolapse or prevention.

- Vaginal Pessaries: Removable devices made of silicone or rubber inserted into the vagina to hold the uterus and other organs in place. A good option for symptomatic relief, especially if surgery is not desired or possible.

- Surgical:

- Surgery aims to repair the weakened pelvic floor tissues and return the organs to their correct position.

- Hysterectomy (Uterus Removal): Often part of surgical repair for uterine prolapse, followed by stitching the top of the vagina to stable ligaments to prevent vaginal vault prolapse.

- Uterine Suspension: Techniques to reattach the uterus to other pelvic structures, preserving the uterus (for women who still want to have children).

- Repair of other associated prolapses (cystocele, rectocele) is often done at the same time.

- The choice of treatment depends on the severity of the prolapse, the woman's age and overall health, her symptoms, desire for future pregnancies, and personal preference.

5. Explain Mullerian anomalies with examples and their implications on fertility.

Mullerian Anomalies Explained:

- Mullerian anomalies are birth defects of the female reproductive tract.

- They happen very early in development (in the first few months of pregnancy) when two structures called Mullerian ducts do not form, fuse, or clear out properly.

- These ducts are supposed to develop into the uterus, fallopian tubes, cervix, and the upper part of the vagina.

- Problems with this process lead to abnormal shapes or absence of these organs.

Examples of Mullerian Anomalies:

- Septate Uterus: A wall inside the uterine cavity.

- Bicornuate Uterus: A heart-shaped uterus with two horns.

- Unicornuate Uterus: A uterus with only one fully formed side.

- Didelphys Uterus: Two separate uteri.

- Vaginal Agenesis: Absence of the vagina.

- Transverse Vaginal Septum: A blocking wall in the vagina.

Implications on Fertility and Pregnancy:

- Infertility: Some anomalies can make it harder to get pregnant. For instance, a severe septum or very abnormal uterine shape might make it difficult for an embryo to implant or grow. Anomalies affecting the fallopian tubes (though less common as a primary Mullerian issue) can also cause infertility.

- Recurrent Miscarriage: This is a major problem with certain anomalies, particularly the septate uterus. The poor blood supply in the septum can prevent a pregnancy from developing correctly, leading to repeated losses early in pregnancy.

- Preterm Birth: An irregularly shaped uterus may not stretch properly as the pregnancy progresses, increasing the risk of the baby being born too early.

- Fetal Malposition: The baby might not be able to get into the head-down position easily in an abnormally shaped uterus, leading to breech presentation or other positions requiring a Cesarean section.

- Obstructed Labor: If there are associated cervical or vaginal anomalies (like a rigid septum), they can block the baby's passage during delivery.

- Vaginal Agenesis (MRKH Syndrome): While ovaries are usually functional (meaning eggs are produced), pregnancy is not possible because the uterus is absent. Genetic children can be had through assisted reproductive technologies like IVF and surrogacy.

6. Discuss the causes and management of imperforate hymen in adolescent girls.

Causes of Imperforate Hymen:

- This is a congenital condition, meaning it is present at birth.

- During the development of the female reproductive organs in the womb, the hymen is supposed to have an opening.

- An imperforate hymen occurs when this opening doesn't form completely, leaving the hymen as a solid membrane covering the vaginal entrance.

- It's a developmental issue, not caused by infection or injury.

Management in Adolescent Girls:

- Imperforate hymen is usually diagnosed in adolescence when a girl does not start menstruating and develops monthly pelvic pain.

- The main treatment is a simple surgical procedure called a **hymenotomy** or **hymenectomy**.

- This involves making a small cut or removing a portion of the hymen to create an opening for menstrual blood to escape.

- The procedure is usually minor and done under anesthesia.

- It is important to perform this relatively soon after diagnosis to relieve pain and prevent long-term complications from the buildup of menstrual blood, such as pressure on the urinary tract or potential effects on fertility (though less common).

- After the procedure, normal menstruation can begin, and sexual function is usually possible once healed.

7. Write an essay on pelvic organ prolapse: types, risk factors, signs and management.

Pelvic organ prolapse is a condition where organs in the pelvis, such as the uterus, bladder, rectum, or vagina, drop down from their normal positions and bulge into or outside the vagina. This happens when the pelvic floor, a strong set of muscles and tissues that support these organs, becomes weak or damaged.

Types of Pelvic Organ Prolapse:

- Cystocele: The bladder bulges into the front wall of the vagina.

- Rectocele: The rectum bulges into the back wall of the vagina.

- Uterine Prolapse: The uterus descends into the vagina.

- Enterocele: The small intestine bulges into the upper part of the vagina.

- Vaginal Vault Prolapse: The top of the vagina collapses after a hysterectomy (removal of the uterus).

Risk Factors:

- Vaginal Childbirth: The stretching and strain during vaginal delivery, especially difficult births, large babies, or multiple pregnancies, significantly weaken the pelvic floor.

- Aging: The natural process of getting older leads to loss of muscle strength and tissue elasticity.

- Menopause: Decreased estrogen levels after menopause contribute to weakening of pelvic tissues.

- Increased Abdominal Pressure:

- Chronic cough (e.g., from smoking or respiratory conditions).

- Chronic constipation and straining during bowel movements.

- Heavy lifting.

- Obesity.

- Surgery: Previous pelvic surgeries can sometimes weaken support structures.

- Genetics: Some women may have weaker connective tissues from birth.

Signs and Symptoms:

- Symptoms vary from mild to severe and may worsen throughout the day or after physical activity.

- Vaginal Bulge or Lump: A feeling of something coming down or out of the vagina.

- Pelvic Pressure/Heaviness: A feeling of fullness, aching, or dragging in the lower abdomen or pelvis.

- Urinary Symptoms: Difficulty emptying the bladder, frequent urination, urgent need to urinate, or leakage of urine (stress incontinence).

- Bowel Symptoms: Difficulty passing stool, needing to push on the vagina to empty the rectum (splinting), or feeling of incomplete emptying.

- Pain or Discomfort: Lower back ache or pain during sexual intercourse.

Management:

- Treatment options depend on the type and severity of prolapse, the woman's symptoms, age, health, desire for future pregnancies, and personal choice.

- Conservative (Non-Surgical) Management:

- Lifestyle Changes: Losing weight, managing constipation, treating chronic cough, avoiding heavy lifting.

- Pelvic Floor Muscle Training (Kegel Exercises): Strengthening the muscles to provide better support. Most helpful for mild prolapse or preventing progression.

- Vaginal Pessaries: Removable devices inserted into the vagina to physically support the prolapsed organs. Need to be fitted and cleaned regularly.

- Surgical Management:

- Surgery aims to restore the normal anatomy and function of the pelvic organs.

- The type of surgery depends on the specific organs prolapsed. It may involve repairing the weakened tissues using stitches, or sometimes using surgical mesh for reinforcement.

- For uterine prolapse, surgery might involve removing the uterus (hysterectomy) and providing support for the top of the vagina, or suspending the uterus to ligaments to keep it in place (uterus preservation).

- Cystocele and rectocele repairs involve tightening the tissues supporting the bladder and rectum, respectively.

- Patients should discuss the risks, benefits, and success rates of different options with their doctor.

8. Describe uterine inversion: causes, diagnosis, emergency management, and prevention.

Uterine inversion is a rare but very serious complication that can happen immediately after childbirth. It means the uterus turns partially or completely inside out, pulling the top part down through the cervix. It requires urgent medical attention.

Causes:

- Uterine inversion usually happens during the third stage of labor (after the baby is born but before the placenta is delivered).

- Excessive Cord Traction: The most common cause is pulling too hard on the umbilical cord before the placenta has separated properly from the uterine wall, especially if the uterus is relaxed.

- Uterine Atony: A uterus that is not contracting well after delivery is more prone to inversion.

- Placenta Implantation: If the placenta is attached to the top part of the uterus (fundus), this area may be pulled down when the placenta is delivered.

- Other Factors: Short umbilical cord, rapid labor, use of certain medications that relax the uterus, or a history of previous inversion can increase the risk.

Diagnosis:

- Diagnosis is usually made quickly based on signs observed immediately after delivery.

- Severe Pain: The woman experiences sudden, severe pain in the lower abdomen.

- Postpartum Hemorrhage: There is often significant and sudden heavy bleeding.

- Fundus Not Palpable: When the doctor or midwife feels the abdomen, they cannot feel the top of the uterus in its normal position.

- Visual Inspection: The inverted uterus or cervix may be seen coming through the vagina or even outside the body.

- Shock: Due to severe pain and blood loss, the woman can quickly develop signs of shock (low blood pressure, fast heart rate, pale skin).

Emergency Management:

- This is a life-threatening emergency needing immediate action.

- Call for Help: Quickly alert senior medical staff, including obstetricians and anesthesiologists.

- Resuscitation: Give intravenous fluids immediately to treat shock and control bleeding. Blood transfusion is often needed.

- Manual Replacement: The most important and urgent step is to manually push the inverted uterus back into its normal position using a gloved hand inserted into the vagina. This must be done as soon as possible.

- Uterine Relaxants: Medications (like terbutaline or magnesium sulfate) may be given temporarily to relax the uterus and make manual replacement easier.

- Uterotonics: Once the uterus is back in place, medications (like oxytocin) are given to make the uterus contract and stay in place, and to control bleeding.

- Surgical Management: If manual replacement fails, surgery is required to reposition the uterus.

Prevention:

- Proper management of the third stage of labor is key.

- Controlled Cord Traction: Only apply gentle traction to the umbilical cord to deliver the placenta *after* confirming signs that the placenta has separated and while applying counter-pressure above the pubic bone.

- Avoid Excessive Cord Pulling: Do not pull hard on the cord, especially if the uterus is relaxed.

- Check Uterine Tone: Ensure the uterus is contracting well after delivery before attempting placental removal.

- Be vigilant for signs of inversion, especially in women with risk factors.

9. Discuss the surgical interventions available for correcting structural abnormalities of the female genital tract.

Surgery is often used to correct congenital structural problems of the female genital tract, particularly when they cause symptoms like blocked menstruation, pain, difficulty with sex, or affect the ability to have a successful pregnancy. The type of surgery depends on the specific abnormality:

Surgical Interventions:

- Hymenotomy/Hymenectomy:

- Purpose: To open up an imperforate or abnormally thick hymen.

- Procedure: A small incision or removal of the obstructing hymen tissue.

- Used For: Imperforate hymen causing blocked menstrual flow.

- Vaginal Septum Resection:

- Purpose: To remove a transverse or longitudinal vaginal septum.

- Procedure: Surgical cutting and removal of the septum tissue.

- Used For: Vaginal septums causing blocked menstrual flow, painful intercourse, or potential problems during childbirth.

- Hysteroscopic Septum Resection:

- Purpose: To remove a septum that divides the inside of the uterus.

- Procedure: Done using a hysteroscope (camera) inserted through the cervix. The septum is cut and removed from inside the uterus. Minimally invasive.

- Used For: Septate uterus causing recurrent miscarriages or infertility.

- Uterine Reconstruction (Metroplasty):

- Purpose: To reshape or unify an abnormally formed uterus.

- Procedure: Various techniques, often open abdominal surgery, to reshape a bicornuate or other complex uterine anomaly. Less common now than hysteroscopic septum resection.

- Used For: Selected complex uterine anomalies impacting pregnancy, though benefits can vary.

- Vaginoplasty:

- Purpose: To create a functional vagina.

- Procedure: Surgical creation of a vaginal canal using methods like skin grafts, bowel segments, or other tissues.

- Used For: Vaginal agenesis (absence of the vagina), often as part of MRKH syndrome.

- Laparoscopy:

- Role: Often used for diagnosis and sometimes for surgical correction (e.g., accessing a rudimentary horn of a unicornuate uterus or assisting with complex vaginal/uterine reconstruction). It allows visualization of the pelvic organs through small incisions.

The choice of surgery depends on the specific anomaly, its severity, the symptoms it causes, and the patient's future reproductive goals.

10. Explain the impact of structural abnormalities of the female genital tract on reproduction and psychosocial wellbeing.

Structural abnormalities of the female genital tract, whether present from birth or developed later, can have significant effects on both a woman's ability to have children and her emotional and social health.

Impact on Reproduction:

- Infertility: Some anomalies can make it difficult or impossible to conceive naturally. For example, a complete vaginal blockage prevents intercourse, and severe uterine malformations may hinder implantation or development.

- Recurrent Miscarriage: Certain uterine shapes, especially a septate uterus, are strongly linked to repeated early pregnancy losses.

- Preterm Birth: Abnormal uterine shapes can lead to the baby being born too early because the uterus cannot expand normally.

- Complications during Pregnancy and Birth: Anomalies can increase risks like poor fetal growth, placental problems, or require a Cesarean section due to difficult labor or the baby's position.

- Primary Amenorrhea: Conditions like absent uterus or complete vaginal blockage cause a girl not to start menstruating, which is a clear sign of a reproductive system issue.

Impact on Psychosocial Wellbeing:

- Emotional Distress: Discovering a structural abnormality can lead to feelings of shock, sadness, anger, and confusion.

- Anxiety and Depression: Coping with infertility, recurrent pregnancy loss, the need for multiple medical appointments and procedures, and the uncertainty of outcomes can significantly impact mental health.

- Body Image Issues: Anomalies, especially those affecting the vagina or external appearance, can affect a woman's self-esteem and how she feels about her body.

- Impact on Relationships: Difficulties with sexual intimacy due to pain or structural issues can strain relationships with partners. Infertility can also put stress on a couple.

- Social Isolation: Some women may feel different or isolated from peers who do not face similar challenges, particularly regarding menstruation, sexual activity, or childbearing.

- Identity Concerns: For young women diagnosed around puberty, understanding their condition and its implications for their future can affect their developing identity and sense of womanhood.

Gynecology Question for Revision - Topic 2

This section covers Menstrual Disorders like amenorrhea, dysmenorrhea, menorrhagia, and PMS.

SECTION A: Multiple Choice Questions (40 Marks)

1. Which of the following is a type of menstrual disorder?

2. Primary amenorrhea is defined as:

3. Menorrhagia refers to:

4. Dysmenorrhea is best described as:

5. Oligomenorrhea refers to:

6. A common cause of secondary amenorrhea is:

7. Which hormone is primarily responsible for regulating menstruation?

8. Premenstrual syndrome (PMS) includes all EXCEPT:

9. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) commonly causes:

10. The most appropriate test for confirming amenorrhea is:

SECTION B: Fill in the Blanks (10 Marks)

1. ________ is defined as the absence of menstrual periods.

2. Painful menstruation is medically termed as ________.

3. Menstrual flow that lasts longer than 7 days is called ________.

4. ________ is the hormone responsible for the proliferation of the endometrium.

5. A woman who has never menstruated is said to have ________ amenorrhea.

6. ________ syndrome is a common endocrine disorder causing menstrual irregularities.

7. The average menstrual cycle length is about ________ days.

8. Hormonal imbalance is a common cause of ________ dysfunction.

9. Premenstrual syndrome occurs in the ________ phase of the menstrual cycle.

10. ________ is used to describe menstruation occurring less frequently than every 35 days.

SECTION C: Short Essay Questions (10 Marks)

1. Define dysmenorrhea and list two types.

Definition:

- Dysmenorrhea is the medical term for painful menstrual periods, characterized by cramping pain in the lower abdomen that may spread to the back or thighs.

- The pain usually begins just before or at the start of menstruation and lasts for 1 to 3 days.

Two Types:

- Primary Dysmenorrhea: Painful periods that are not caused by an underlying medical condition of the reproductive organs. It's thought to be caused by chemicals called prostaglandins in the uterus that cause muscle contractions.

- Secondary Dysmenorrhea: Painful periods that are caused by an underlying medical condition of the reproductive organs, such as endometriosis, uterine fibroids, adenomyosis, or pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). The pain often starts earlier in the cycle and lasts longer than typical menstrual cramps.

2. Describe three common causes of secondary amenorrhea.

Secondary amenorrhea is when periods stop after they have already started regularly. Common causes include:

- Pregnancy: This is the most frequent cause. When a woman becomes pregnant, her menstrual cycle stops as the body supports the developing fetus.

- Breastfeeding (Lactational Amenorrhea): Hormones produced during breastfeeding can suppress ovulation and menstruation, causing periods to stop or become irregular.

- Significant Weight Loss or Excessive Exercise: Extreme dieting, very low body weight, or intense physical training can disrupt the hormonal signals needed for menstruation to occur.

- Stress: High levels of physical or emotional stress can affect the part of the brain that controls the menstrual cycle, leading to missed periods.

- Certain Medical Conditions: Hormonal disorders like Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS), thyroid problems, or problems with the pituitary gland can disrupt menstruation.

3. Outline the symptoms of premenstrual syndrome (PMS).

Premenstrual syndrome (PMS) involves a range of physical and emotional symptoms that happen in the week or two before menstruation. Symptoms vary among women but commonly include:

- Emotional Symptoms: Mood swings, irritability, anxiety, depression, feeling tearful, difficulty concentrating, feeling overwhelmed.

- Physical Symptoms: Bloating, breast tenderness or swelling, headache, fatigue, changes in appetite (cravings), joint or muscle pain, acne flares, and digestive issues (constipation or diarrhea).

4. List three complications of untreated menorrhagia.

Untreated heavy menstrual bleeding (menorrhagia) can lead to several health problems:

- Anemia: Significant blood loss over time can lead to iron deficiency anemia, causing fatigue, weakness, paleness, and shortness of breath.

- Severe Pain: Menorrhagia can sometimes be associated with severe cramping or pelvic pain.

- Disruption to Quality of Life: Heavy bleeding can interfere with daily activities, work, social events, and exercise due to discomfort, fear of accidents, and fatigue.

- Increased Risk of Other Conditions: The underlying cause of menorrhagia (like fibroids or polyps) can potentially lead to other complications if not treated.

5. Explain the difference between oligomenorrhea and polymenorrhea.

- Oligomenorrhea: This refers to menstrual periods that occur *infrequently*. The time between periods is longer than a normal cycle, usually defined as cycles lasting more than 35 days but less than 6 months.

- Polymenorrhea: This refers to menstrual periods that occur *frequently*. The time between periods is shorter than a normal cycle, usually defined as cycles lasting less than 21 days.

6. State three diagnostic tests used to evaluate amenorrhea.

When investigating the cause of amenorrhea (absent periods), doctors may use several tests:

- Pregnancy Test: This is always the first test for secondary amenorrhea in women of reproductive age to rule out pregnancy.

- Hormone Blood Tests: Measuring levels of hormones like FSH, LH, estrogen, prolactin, thyroid hormones, and androgens can help identify hormonal imbalances or problems with the ovaries, pituitary gland, or hypothalamus.

- Imaging Tests:

- **Ultrasound:** To check for abnormalities in the uterus and ovaries, such as absence of the uterus, structural problems, or polycystic ovaries.

- **MRI:** May be used for more detailed images of the brain (pituitary gland) or pelvic organs if needed.

- Genetic Testing: May be done in cases of primary amenorrhea with abnormal development of reproductive organs.

7. Describe how PCOS can lead to menstrual disorders.

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) is a hormonal disorder that commonly causes menstrual problems:

- Anovulation or Irregular Ovulation: PCOS disrupts the normal process of ovulation (release of an egg from the ovary). Instead of ovulating regularly, women with PCOS may ovulate infrequently or not at all.

- Hormonal Imbalance: PCOS involves higher-than-normal levels of male hormones (androgens) and often insulin resistance. These hormonal imbalances interfere with the signals from the brain to the ovaries that control the menstrual cycle.

- Effect on Uterine Lining: Without regular ovulation and progesterone production, the uterine lining may not develop and shed normally, leading to irregular, infrequent, or absent periods.

8. What are three possible side effects of hormonal therapy for menstrual disorders?

Hormonal therapies, such as birth control pills, progesterone, or GnRH agonists, are often used to treat menstrual disorders. Possible side effects can include:

- Nausea and Vomiting: Especially when starting treatment.

- Headache: Can be a common side effect.

- Mood Changes: Some women may experience mood swings, irritability, or depression.

- Breast Tenderness: Feeling of soreness or swelling in the breasts.

- Weight Changes: Some women may experience slight weight gain or fluid retention.

- Spotting or Breakthrough Bleeding: Bleeding between expected periods can occur, especially with hormonal contraceptives.

- More Serious Risks (Less Common): Increased risk of blood clots, stroke, or heart attack, particularly with estrogen-containing therapies in certain individuals.

9. Mention two lifestyle changes that can improve symptoms of PMS.

Lifestyle changes can be very effective in managing PMS symptoms:

- Regular Exercise: Engaging in regular physical activity (like walking, jogging, swimming) can help reduce stress, improve mood, and alleviate physical symptoms like bloating and fatigue.

- Dietary Modifications:

- Eating a balanced diet rich in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains.

- Reducing intake of salt (to decrease bloating), sugar, caffeine, and alcohol, especially in the week or two before periods.

- Ensuring adequate intake of calcium and vitamin D, and potentially magnesium and vitamin B6, which may help reduce some symptoms.

- Stress Management Techniques: Practicing relaxation techniques like yoga, meditation, deep breathing exercises, or getting enough sleep can help reduce the emotional symptoms of PMS.

10. Briefly outline the nursing care for a patient with dysmenorrhea.

Nursing care for a patient with dysmenorrhea (painful periods) focuses on pain management, education, and support:

- Pain Assessment and Management: Assess the severity, location, and timing of pain. Administer prescribed pain relief medications (like NSAIDs) as ordered and evaluate their effectiveness.

- Education: Teach the patient about the causes of dysmenorrhea (especially primary vs. secondary), the importance of medication adherence, and non-pharmacological pain relief methods.

- Non-Pharmacological Relief: Advise and assist with comfort measures like applying heat (hot water bottle or heating pad) to the abdomen, rest, gentle exercise, and relaxation techniques.

- Lifestyle Advice: Provide education on lifestyle changes that may help, such as dietary adjustments and regular exercise.

- Emotional Support: Listen to the patient's concerns and provide reassurance. Acknowledge the impact pain has on her life.

- Referral: Recognize signs of secondary dysmenorrhea and ensure the patient is referred for further medical evaluation if needed.

SECTION D: Long Essay Questions (10 Marks Each)

1. Discuss the causes, clinical features, investigations, and management of menorrhagia.

What is Menorrhagia?

- Menorrhagia is abnormally heavy or prolonged menstrual bleeding.

- It means having periods that are heavy enough to interfere with daily activities or last longer than 7 days.

- It is a common menstrual disorder that can significantly impact a woman's health and quality of life.

Causes of Menorrhagia:

- Uterine Fibroids: Non-cancerous growths in the uterus, especially those that bulge into the uterine cavity, are a very common cause of heavy bleeding.

- Uterine Polyps: Small growths in the lining of the uterus (endometrium) can also cause heavy or prolonged bleeding.

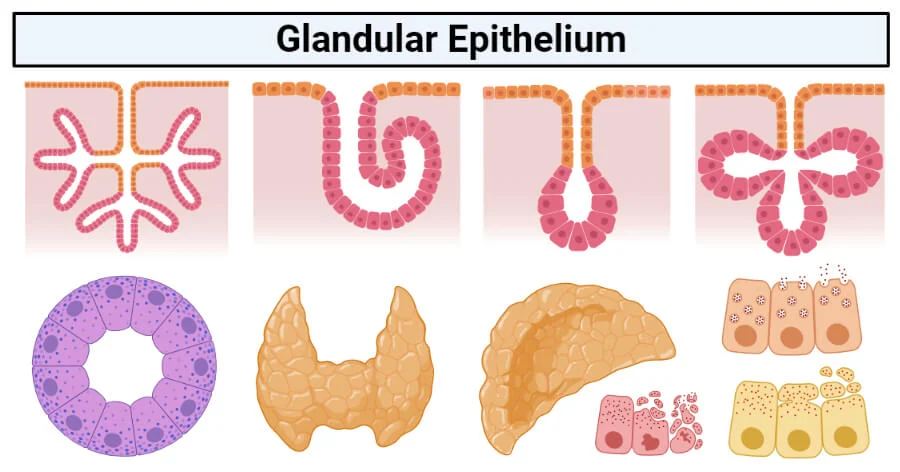

- Adenomyosis: A condition where the tissue that normally lines the uterus grows into the muscular wall of the uterus, causing thickening and heavy, painful periods.

- Hormonal Imbalances: Problems with the balance of estrogen and progesterone, often due to conditions like PCOS or problems with ovulation, can lead to the uterine lining becoming too thick and shedding heavily.

- Bleeding Disorders: Rare inherited conditions that affect blood clotting can cause excessive bleeding, including heavy periods.

- Intrauterine Devices (IUDs): Especially non-hormonal copper IUDs, can sometimes cause heavier menstrual bleeding.

- Pregnancy Complications: Miscarriage or ectopic pregnancy can sometimes present with abnormal bleeding.

- Cancer: Although less common, uterine or cervical cancer can cause abnormal and heavy bleeding, particularly in older women.

Clinical Features (Signs and Symptoms):

- Soaking through one or more sanitary pads or tampons every hour for several consecutive hours.

- Needing to use double sanitary protection (e.g., two pads) to control menstrual flow.

- Needing to change sanitary protection during the night.

- Bleeding for longer than 7 days.

- Passing large blood clots.

- Symptoms of anemia, such as fatigue, weakness, paleness, dizziness, and shortness of breath.

- Severe cramping or pelvic pain associated with the heavy bleeding.

Investigations:

- Medical History and Physical Exam: The doctor will ask about the bleeding pattern and other symptoms and perform a pelvic exam.

- Blood Tests: To check for anemia (complete blood count) and assess hormone levels or blood clotting disorders.

- Pelvic Ultrasound: This is a common imaging test to look for structural causes like fibroids or polyps in the uterus and ovaries.

- Endometrial Biopsy: A small sample of the uterine lining is taken to check for abnormal cells or cancer, especially in women over 40 or those with risk factors.

- Hysteroscopy: A procedure where a small camera is inserted into the uterus to visualize the inside of the cavity and identify polyps, fibroids, or other abnormalities.

- Sonohysterography: Saline is instilled into the uterus during ultrasound to get a clearer view of the uterine cavity.

Management:

- Management depends on the cause, severity, the woman's age, desire for future pregnancies, and overall health.

- Medical Management:

- NSAIDs (Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs): Like ibuprofen, can reduce bleeding and pain.

- Tranexamic Acid: A medication that helps blood clot and reduces menstrual flow.

- Hormonal Therapy:

- Combined Oral Contraceptives (Birth Control Pills): Regulate cycles and reduce bleeding.

- Progesterone Therapy: Can help regulate bleeding, especially in cases of hormonal imbalance.

- Hormonal IUD (Levonorgestrel-releasing IUD): Very effective at reducing menstrual bleeding.

- GnRH Agonists: Medications that temporarily stop menstruation and shrink fibroids, used for a limited time due to side effects.

- Surgical Management: Used when medical treatment fails or for specific causes like large fibroids or polyps.

- Polypectomy: Surgical removal of polyps (often done during hysteroscopy).

- Myomectomy: Surgical removal of fibroids (preserving the uterus).

- Endometrial Ablation: A procedure to destroy the lining of the uterus to reduce or stop bleeding (not suitable for women who wish to have future pregnancies).

- Hysterectomy: Surgical removal of the uterus. This is a permanent solution for severe menorrhagia when other treatments are ineffective or not desired.

- Iron Supplementation: To treat or prevent iron deficiency anemia caused by heavy bleeding.

2. Define amenorrhea. Distinguish between primary and secondary amenorrhea and outline their causes and treatment.

Definition of Amenorrhea:

- Amenorrhea is the absence of menstruation.

- It means a woman or girl is not having menstrual periods.

- It is a symptom, not a disease itself, and requires investigation to find the underlying cause.

Primary vs. Secondary Amenorrhea:

- Primary Amenorrhea:

- Definition: When a girl has not started having her menstrual periods by the age of 16, or by 14 if she hasn't shown any signs of puberty (like breast development).

- Cause: Usually due to problems with the development of the reproductive organs or genetic or chromosomal abnormalities.

- Secondary Amenorrhea:

- Definition: When a woman who has previously had regular menstrual periods stops having them for 3 months or more, or stops having irregular periods for 6 months or more.

- Cause: Usually due to acquired conditions like pregnancy, hormonal imbalances, medical conditions, or lifestyle factors.

Causes:

- Causes of Primary Amenorrhea:

- Genetic or Chromosomal Abnormalities: Conditions like Turner syndrome (missing an X chromosome).

- Problems with Ovarian Development: Ovaries not forming correctly or not containing eggs.

- Problems with the Brain (Hypothalamus or Pituitary): Issues affecting the release of hormones (FSH, LH) that stimulate the ovaries.

- Structural Problems: Absence of the uterus or vagina (Mullerian agenesis), or a blockage like an imperforate hymen or vaginal septum.

- Delayed Puberty: Sometimes puberty is just delayed, and periods will start later naturally.

- Causes of Secondary Amenorrhea:

- Pregnancy: The most common cause.

- Breastfeeding.

- Menopause or Perimenopause: The natural end of menstruation.

- Hormonal Contraceptives: Some types can stop periods.

- Stress.

- Significant Weight Loss, Low Body Weight, or Excessive Exercise.

- Hormonal Imbalances:

- Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS).

- Thyroid problems (overactive or underactive thyroid).

- High levels of prolactin (hormone related to milk production).

- Problems with the adrenal glands.

- Chronic Illnesses.

- Certain Medications.

- Uterine Scarring: Sometimes caused by procedures like D&C (dilation and curettage).

Treatment:

- Treatment depends entirely on the underlying cause.

- Treating the Cause: This is the primary focus.

- For pregnancy, no treatment for amenorrhea is needed.

- For hormonal imbalances (like PCOS, thyroid problems), medications are given to correct the hormone levels.

- For structural problems, surgery may be needed to open blockages or reconstruct organs.

- For stress or weight-related causes, lifestyle changes and support are provided.

- Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT): May be used if amenorrhea is due to ovarian failure or absence of ovaries, to provide necessary hormones.

- Ovulation Induction: If the cause is lack of ovulation and pregnancy is desired, medications can be given to stimulate ovulation.

- Addressing Underlying Conditions: Treating any chronic illness contributing to amenorrhea.

- Counseling and Support: Essential for helping individuals cope with the diagnosis and its implications.

3. Explain dysmenorrhea in detail, including types, causes, signs and symptoms, and nursing interventions.

What is Dysmenorrhea?

- Dysmenorrhea is painful menstruation.

- It is one of the most common gynecological complaints among women of reproductive age.

- The pain is typically cramping and located in the lower abdomen, but can also be a dull, continuous ache.

Types:

- Primary Dysmenorrhea:

- Painful periods that start within 6-12 months of first menstruation (menarche).

- There is no underlying problem with the reproductive organs.

- Caused by the uterus producing too much of chemicals called prostaglandins, which cause the uterine muscles to contract forcefully and reduce blood flow, leading to pain.

- Pain typically starts just before or with the onset of bleeding and lasts 1-3 days.

- Secondary Dysmenorrhea:

- Painful periods that develop later in life, usually after years of painless or less painful periods.

- Caused by an identifiable problem with the reproductive organs.

- Underlying causes include endometriosis, uterine fibroids, adenomyosis, pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), ovarian cysts, or structural abnormalities.

- Pain may start earlier in the menstrual cycle (days or weeks before bleeding) and last longer, sometimes throughout the period and even after it ends. It may also worsen over time.

Signs and Symptoms:

- Lower Abdominal Cramps: Pain that is often described as cramping or aching in the lower belly, just above the pubic bone.

- Pain Radiating: Pain may spread to the lower back and inner thighs.

- Other Associated Symptoms:

- Nausea and vomiting.

- Diarrhea or constipation.

- Headache.

- Fatigue.

- Bloating.

- Dizziness or lightheadedness.

- In primary dysmenorrhea, symptoms are typically limited to the time of menstruation. In secondary dysmenorrhea, associated symptoms of the underlying cause (e.g., heavy bleeding with fibroids, painful intercourse with endometriosis) may also be present, and the pain pattern is often different.

Nursing Interventions:

- Assess Pain: Evaluate the severity, characteristics (cramping, aching), location, duration, and timing of the pain, and how it affects daily activities.

- Administer Pain Relief: Give prescribed medications (like NSAIDs such as ibuprofen or naproxen, or hormonal contraceptives) as ordered and monitor their effectiveness. Educate on taking NSAIDs just before pain starts or at the onset of bleeding for best results.

- Provide Comfort Measures:

- Encourage rest in a comfortable position.

- Apply heat to the abdomen (heating pad or hot water bottle) as heat helps relax uterine muscles.

- Suggest warm baths.

- Education:

- Explain the difference between primary and secondary dysmenorrhea and when further medical evaluation is needed.

- Educate on the importance of regular exercise and a healthy diet (reducing caffeine, salt, and sugar intake during the premenstrual phase).

- Teach relaxation techniques (deep breathing, meditation) to help cope with pain.

- Support: Listen to the patient's experiences and validate her pain. Provide emotional support and reassurance.

- Documentation: Record pain levels, interventions, and the patient's response.

- Referral: If symptoms are severe, unresponsive to simple measures, or suggest secondary dysmenorrhea, ensure the patient is referred back to the doctor for further investigation and management.

4. Discuss the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) as a cause of menstrual disorders.

What is Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS)?

- PCOS is a common hormonal disorder affecting women of reproductive age.

- It is characterized by an imbalance of reproductive hormones.

- It often leads to irregular or absent periods, development of small cysts on the ovaries, and increased levels of male hormones (androgens).

- PCOS is a significant cause of menstrual disorders and infertility.

Pathophysiology (How it Causes Problems):

- Hormonal Imbalance: Women with PCOS often have:

- Higher than normal levels of androgens (male hormones like testosterone).

- Irregular levels of LH (luteinizing hormone) compared to FSH (follicle-stimulating hormone).

- High levels of insulin (insulin resistance), which can further increase androgen production.

- Ovulatory Dysfunction: The hormonal imbalance disrupts the normal process of follicle development and ovulation. Follicles may start to grow but do not mature and release an egg. Instead, they accumulate in the ovaries as small cysts. The lack of regular ovulation leads to irregular or absent periods.

- Increased Androgens: High androgen levels contribute to symptoms like excess body hair (hirsutism), acne, and sometimes hair loss on the scalp.

Diagnosis:

- Diagnosis is based on meeting at least two out of three main criteria (Rotterdam criteria):

- Irregular or Absent Ovulation: Leading to irregular or absent menstrual periods.

- High Androgen Levels: Shown by blood tests or clinical signs like severe acne or excess hair growth.

- Polycystic Ovaries on Ultrasound: Ovaries that are larger than normal and contain multiple small follicles (cysts) around the edge. (Note: Having polycystic ovaries on ultrasound alone does not mean a woman has PCOS).

- Other tests may include blood tests to check for other hormone problems (like thyroid issues or high prolactin) and sometimes blood sugar tests to check for diabetes.

Treatment for Menstrual Disorders in PCOS:

- Treatment focuses on managing symptoms and reducing long-term health risks (like diabetes and heart disease).

- Lifestyle Changes:

- Weight Loss: Even a modest weight loss can significantly improve hormonal balance and menstrual regularity in overweight women with PCOS.

- Healthy Diet and Exercise: To manage weight and improve insulin sensitivity.

- Medical Management:

- Combined Oral Contraceptives (Birth Control Pills): These are a common treatment to regulate menstrual cycles, reduce androgen levels (improving acne and hair growth), and protect the uterine lining from becoming too thick (reducing risk of uterine cancer).

- Progesterone Therapy: Taking progesterone for a few days each month can help induce regular withdrawal bleeding and protect the uterine lining if pregnancy is not desired.

- Metformin: A medication typically used for diabetes, but it can help improve insulin sensitivity and, in some women with PCOS, can help restore regular periods.

- Medications to Reduce Androgens: Such as spironolactone, can help with excess hair growth and acne.

- Ovulation Induction Medications: If pregnancy is desired, medications like Clomiphene citrate or Letrozole are used to stimulate ovulation.

5. Describe premenstrual syndrome (PMS) under the following headings: causes, symptoms, diagnosis, and nursing care.

What is Premenstrual Syndrome (PMS)?

- PMS is a common condition affecting many women during their reproductive years.

- It involves a predictable pattern of physical, emotional, and behavioral symptoms.

- Symptoms typically occur in the luteal phase (after ovulation) of the menstrual cycle and resolve shortly after menstruation begins.

Causes:

- The exact cause of PMS is not fully understood, but it is believed to be related to the fluctuating levels of hormones, specifically estrogen and progesterone, during the menstrual cycle.

- Sensitivity to these hormonal changes is thought to play a role.

- Brain chemicals (neurotransmitters) like serotonin, which affects mood, may also be involved.

- Other factors like stress, diet (high sugar, caffeine, salt), lack of exercise, and vitamin/mineral deficiencies might contribute or worsen symptoms.

Symptoms:

- Symptoms are wide-ranging and vary from woman to woman. They can be physical or emotional.

- Emotional/Behavioral: Irritability, anxiety, tension, sadness, crying spells, mood swings, difficulty concentrating, feeling overwhelmed, changes in appetite (cravings), sleep problems (insomnia or increased sleep).

- Physical: Bloating, weight gain, breast tenderness or swelling, headache, fatigue, joint or muscle pain, acne flare-ups, abdominal cramps, digestive upset (constipation or diarrhea).

For a diagnosis of PMS, these symptoms must:

- Occur in the week or two before menstruation.

- Improve significantly or disappear within a few days after menstruation starts.

- Be present for at least two consecutive menstrual cycles.

- Cause noticeable distress or interfere with daily life.

Diagnosis:

- There is no single laboratory test to diagnose PMS.

- Diagnosis is primarily based on a detailed medical history and tracking symptoms.

- The woman is usually asked to keep a diary or calendar of her symptoms for 2-3 menstrual cycles, noting the type, severity, and when they occur in relation to her period.

- This helps confirm the cyclical pattern of symptoms necessary for diagnosis.

- The doctor will also rule out other conditions that might cause similar symptoms (like depression, anxiety disorders, thyroid problems, or chronic fatigue syndrome).

Nursing Care:

- Assessment: Ask about the nature, timing, and severity of PMS symptoms and how they impact the woman's life.

- Education:

- Explain what PMS is and that it is a real and common condition.

- Discuss the possible role of hormonal fluctuations.

- Teach symptom tracking as a diagnostic tool and for monitoring treatment effectiveness.

- Lifestyle Counseling:

- Advise on lifestyle modifications that can help manage symptoms, such as regular exercise, stress reduction techniques (yoga, meditation, deep breathing), getting adequate sleep, and dietary changes (reducing salt, sugar, caffeine, alcohol; increasing complex carbohydrates, calcium, magnesium).

- Encourage a healthy and balanced diet.

- Medication Education: If medications are prescribed (e.g., pain relievers, hormonal contraceptives, antidepressants for severe PMS/PMDD), explain how to take them, potential side effects, and what to expect.

- Emotional Support: Provide a supportive environment for the woman to discuss her symptoms and feelings. Validate her experiences.

- Referral: If symptoms are severe or unresponsive to initial measures, refer the patient back to the doctor for consideration of further medical management or counseling.

6. Explain the role of hormonal imbalance in menstrual disorders. Include hormonal feedback mechanisms.

Role of Hormonal Imbalance in Menstrual Disorders:

- The menstrual cycle is tightly controlled by a complex interplay of hormones produced by the hypothalamus, pituitary gland in the brain, and the ovaries.

- When the levels or timing of these hormones are disrupted (hormonal imbalance), it can lead to various menstrual disorders.

- Specific imbalances can cause periods to be irregular, absent, heavy, or painful, and contribute to conditions like PCOS or amenorrhea.

Key Hormones Involved:

- GnRH (Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone): Released by the hypothalamus, signals the pituitary gland.

- FSH (Follicle-Stimulating Hormone): Released by the pituitary, stimulates follicle growth in the ovaries.

- LH (Luteinizing Hormone): Released by the pituitary, triggers ovulation and formation of the corpus luteum.

- Estrogen: Produced by growing follicles in the ovaries, causes uterine lining (endometrium) to thicken.

- Progesterone: Produced by the corpus luteum after ovulation, prepares the uterine lining for pregnancy and maintains it.

- Androgens: (e.g., testosterone) Produced in small amounts by ovaries and adrenal glands; elevated levels can disrupt ovulation (as in PCOS).

- Prolactin: Produced by the pituitary; high levels can inhibit ovulation.

- Thyroid Hormones: Produced by the thyroid gland; imbalances (hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism) can affect menstrual regularity.

Hormonal Feedback Mechanisms:

- The menstrual cycle relies on a feedback loop between the brain and the ovaries.

- Positive Feedback: Rising levels of estrogen from developing follicles signal the pituitary to release a surge of LH. This LH surge triggers ovulation. (Estrogen positively feeds back to the pituitary).

- Negative Feedback:

- Estrogen and progesterone produced by the ovaries also signal the hypothalamus and pituitary to reduce the release of GnRH, FSH, and LH.

- High levels of estrogen and progesterone after ovulation suppress FSH and LH production, preventing further follicle development.

- If pregnancy doesn't occur, estrogen and progesterone levels drop, which then removes the negative feedback and allows FSH and LH to rise again, starting the next cycle.

How Imbalances Cause Disorders:

- If the hypothalamus or pituitary doesn't release hormones correctly (e.g., due to stress, weight extremes, or tumors), the ovaries won't be stimulated, leading to amenorrhea.

- If the ovaries produce too much or too little estrogen or progesterone, the uterine lining won't develop or shed normally, causing irregular or heavy bleeding (menorrhagia, metrorrhagia).

- High androgen levels (like in PCOS) disrupt the delicate balance required for follicle maturation and ovulation, leading to irregular periods or amenorrhea.

- Problems with thyroid hormones or prolactin can interfere with the brain-ovary signals, causing menstrual irregularities.

7. Discuss the impact of nutritional status on menstruation and reproductive health.

Nutritional status plays a vital role in regulating menstruation and overall reproductive health. Both insufficient and excessive body weight, as well as specific nutrient deficiencies, can disrupt the delicate hormonal balance required for normal menstrual cycles.

Impact of Low Body Weight/Under-nutrition:

- Amenorrhea: Being significantly underweight or experiencing rapid, severe weight loss can lead to functional hypothalamic amenorrhea. The body senses it doesn't have enough energy reserves for reproduction, so the hypothalamus reduces the release of GnRH, which in turn lowers FSH and LH. This lack of stimulation causes the ovaries to produce less estrogen, leading to the cessation of menstruation.

- Irregular Periods: Even without complete absence of periods, low body weight can cause irregular or infrequent cycles (oligomenorrhea) due to disrupted ovulation.

- Infertility: Lack of regular ovulation makes it difficult or impossible to conceive.

- Poor Pregnancy Outcomes: If conception does occur, being underweight can increase risks during pregnancy.

- Nutrient Deficiencies: Under-nutrition often means deficiencies in essential vitamins and minerals (like iron, calcium), impacting overall health and potentially affecting hormonal pathways.

Impact of High Body Weight/Obesity:

- Menstrual Irregularities: Obesity is strongly linked to conditions like Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS), which is a major cause of irregular or absent periods due to ovulatory dysfunction. Fat tissue can produce estrogen, and excess fat can lead to insulin resistance, both of which disrupt hormonal balance.

- Heavy Bleeding: Hormonal imbalances in overweight women can sometimes lead to the uterine lining becoming too thick, resulting in heavy or prolonged bleeding (menorrhagia).

- Infertility: Irregular or absent ovulation in obese women can cause infertility.

- Increased Pregnancy Risks: Obesity during pregnancy is associated with higher risks of gestational diabetes, high blood pressure, preterm birth, and other complications.

- Increased Risk of Endometrial Cancer: Long-term exposure to higher estrogen levels from fat tissue can increase the risk of developing cancer of the uterine lining, especially if periods are infrequent.

Impact of Specific Nutrients:

- Iron: Deficiency leads to anemia, often worsened by heavy periods (menorrhagia). Adequate iron intake is crucial.

- Calcium and Vitamin D: Important for bone health, especially if hormonal imbalances lead to low estrogen levels over time, which can affect bone density.

- Other Vitamins and Minerals: B vitamins, magnesium, and omega-3 fatty acids have been studied for their potential role in managing PMS symptoms and supporting hormonal balance.

8. Outline the nursing management of a patient with severe menstrual pain.

Nursing management for a patient experiencing severe menstrual pain (dysmenorrhea) focuses on providing pain relief, offering support, and identifying potential underlying causes:

Nursing Management:

- Pain Assessment:

- Assess the severity, location, character (cramping, sharp, dull), timing (when it starts and stops in relation to bleeding), and duration of the pain using a pain scale.

- Ask about associated symptoms like nausea, vomiting, headache, or back pain.

- Determine how the pain interferes with her daily activities (work, school, sleep, social life).

- Administer Pain Medications:

- Administer prescribed analgesics (painkillers) promptly, usually NSAIDs (like ibuprofen, naproxen) or sometimes stronger medications if ordered.

- Educate the patient on the best way to take NSAIDs – often most effective when started just before or at the very beginning of menstruation.

- Monitor the effectiveness of the medication and for any side effects.

- Implement Non-Pharmacological Pain Relief:

- Encourage rest in a comfortable position.

- Apply heat to the lower abdomen or back using a heating pad or hot water bottle. Heat helps relax the uterine muscles and reduce cramps.

- Suggest warm baths.

- Teach or encourage relaxation techniques such as deep breathing exercises, meditation, or guided imagery.

- Advise gentle exercise if tolerated, as physical activity can sometimes help.

- Provide Education and Counseling:

- Explain the difference between primary and secondary dysmenorrhea and the possible causes of her pain.

- Discuss the importance of a healthy lifestyle, including regular exercise, a balanced diet, and adequate hydration.

- Talk about stress management techniques.

- Educate about the menstrual cycle and why pain occurs.

- Identify Potential Secondary Causes: Be alert for signs and symptoms that might suggest secondary dysmenorrhea (e.g., pain starting later in life, worsening pain, pain present throughout the cycle, association with heavy bleeding or painful intercourse).

- Emotional Support: Severe pain can be distressing. Provide a listening ear, validate her experience of pain, and offer reassurance.

- Documentation: Record the patient's pain level, assessment findings, interventions provided, and her response to treatment.

- Referral: Ensure that patients with severe, persistent, or worsening pain, or those with signs suggestive of secondary dysmenorrhea, are referred back to the doctor for further investigation (e.g., ultrasound) to rule out underlying conditions.

9. Describe the psychosocial effects of menstrual disorders on adolescent girls and appropriate interventions.

Menstrual disorders like severe pain (dysmenorrhea), heavy bleeding (menorrhagia), or irregular/absent periods (amenorrhea) can significantly impact the psychosocial wellbeing of adolescent girls, affecting their emotional health, social life, and performance at school.

Psychosocial Effects:

- Academic Impact: Severe pain or heavy bleeding can cause girls to miss school frequently or find it difficult to concentrate in class, leading to poor academic performance.

- Social Isolation: Pain, fatigue, or fear of accidents due to heavy bleeding can make girls withdraw from social activities, sports, or spending time with friends during their periods.

- Emotional Distress: Chronic pain, unpredictable bleeding, or the inability to participate in activities can lead to frustration, anxiety, irritability, and even depression. Menstrual irregularities can also cause worry about fertility or overall health.

- Poor Self-Esteem and Body Image: Conditions like PCOS with symptoms like acne and excess hair, or the challenges of managing heavy bleeding, can negatively impact a girl's self-image and confidence during a crucial time of development.

- Sleep Disturbances: Pain or the need to frequently change sanitary products can disrupt sleep, leading to fatigue and worsening mood and concentration.

- Family Strain: Managing symptoms and the impact on daily life can sometimes create tension or worry within the family.

Appropriate Interventions:

- Education and Information:

- Provide clear, age-appropriate information about normal menstruation and common disorders.

- Explain the causes of their specific disorder in a way they can understand.

- Reduce fear and stigma by normalizing discussions about menstruation.

- Effective Symptom Management: Ensure pain and bleeding are adequately controlled through medical treatment (medications) and lifestyle changes. Effective physical symptom management is crucial for improving psychosocial outcomes.

- Counseling and Support: Offer or refer for counseling to help girls cope with the emotional impact, anxiety, or depression related to their menstrual disorder. Support groups can also be beneficial.

- School Support: Work with parents and school staff to create a supportive environment. This might include getting accommodations for missed classes, access to restrooms, or support from school nurses.

- Promote Healthy Coping Strategies: Encourage healthy lifestyle habits (exercise, diet, sleep) and stress reduction techniques.

- Open Communication: Encourage open communication between the girl, her parents, and healthcare providers about her symptoms and how she is feeling.

- Address Underlying Causes: Ensure that any underlying medical condition contributing to the menstrual disorder is properly diagnosed and treated.

10. Explain the medical and surgical treatment options available for abnormal uterine bleeding.

Abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) refers to any bleeding from the uterus that is different from normal menstruation (in terms of frequency, regularity, duration, or volume). Treatment options depend on the cause of the AUB, the woman's age, overall health, and desire for future fertility.

Medical Treatment Options:

- NSAIDs (Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs): Like ibuprofen or naproxen. They can reduce blood loss and pain during periods.

- Tranexamic Acid: A non-hormonal medication that helps blood to clot and significantly reduces menstrual flow.

- Hormonal Therapy: These treatments help regulate the menstrual cycle and reduce bleeding by affecting hormone levels or the uterine lining.

- Combined Oral Contraceptives (Birth Control Pills): Regulate cycles, reduce bleeding, and can help with pain.

- Progestin-Only Therapy: Progesterone can be given in various forms (pills, injection, implant) to thin the uterine lining and reduce bleeding.

- Levonorgestrel-Releasing Intrauterine System (LNG-IUS), e.g., Mirena: A hormonal IUD inserted into the uterus that releases progestin locally. It is highly effective at reducing menstrual bleeding, often leading to very light periods or amenorrhea.