HAEMORRHAGE: Nursing Lecture Notes

HAEMORRHAGE: Nursing Lecture Notes

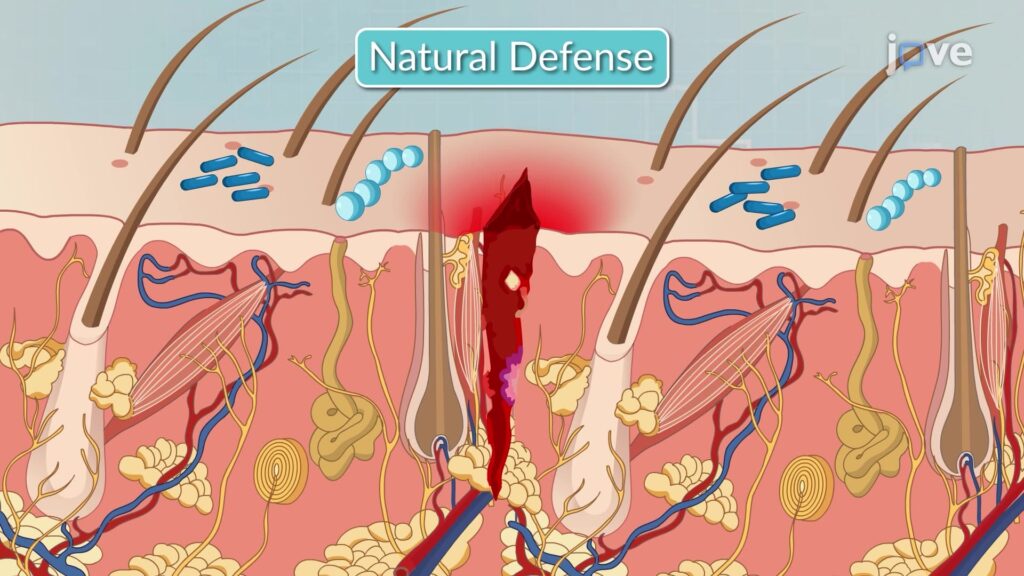

Haemorrhage, commonly known as bleeding, is the loss of blood from the circulatory system, specifically from blood vessels. It is a critical medical condition that, if uncontrolled, can lead to severe physiological compromise and death. The body possesses intrinsic defence mechanisms, primarily through the process of clotting (hemostasis), to prevent excessive blood leakage. However, these mechanisms can be deficient due to underlying diseases, absence of essential clotting factors, or the use of anticoagulant medications.

Types of Haemorrhage

Haemorrhage is classified based on several key characteristics to aid in diagnosis, prognosis, and management. These classifications include:

- The type of blood vessel involved.

- The location or situation of the haemorrhage.

- The time of occurrence or duration of the haemorrhage.

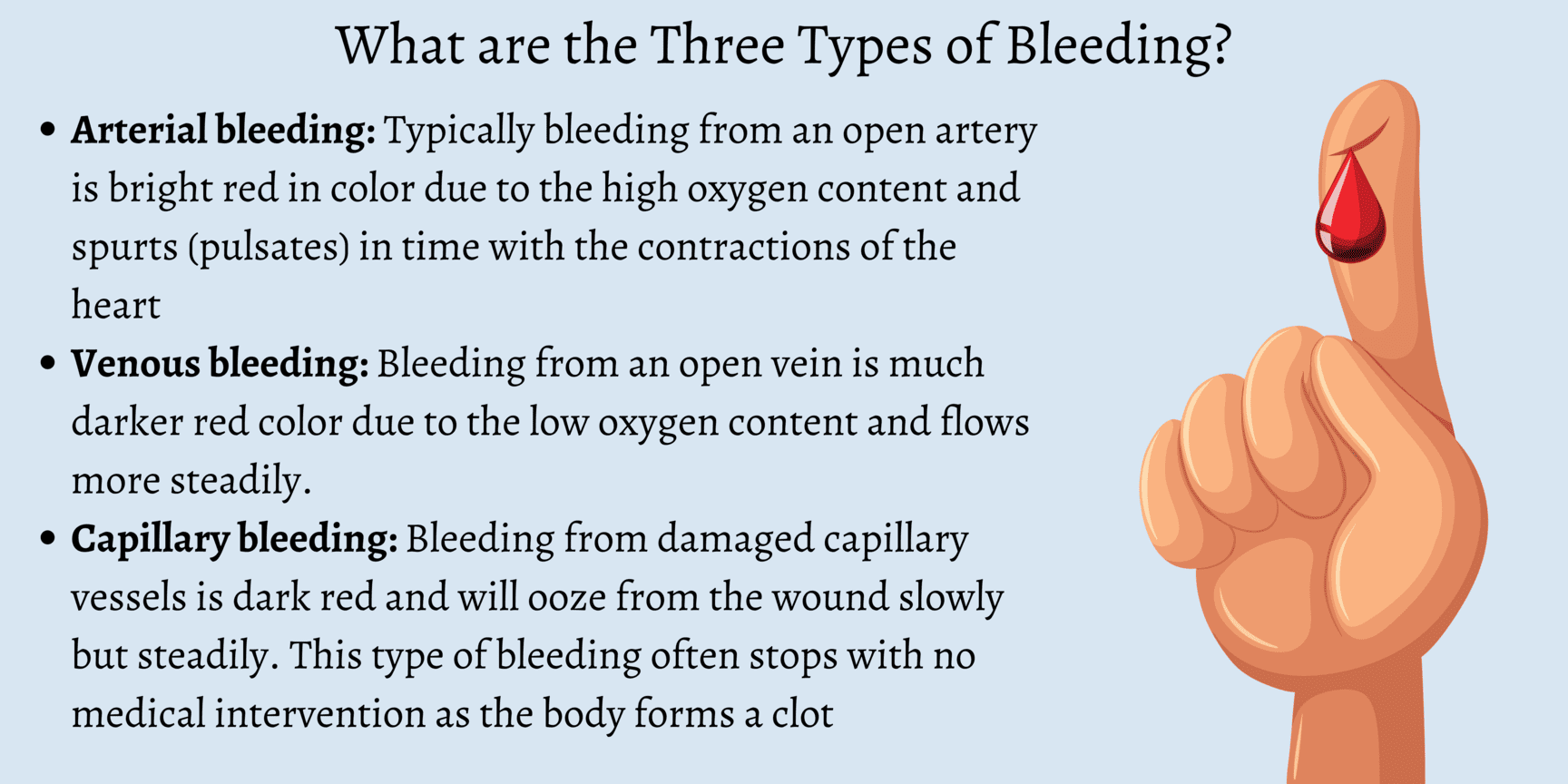

Classification by Blood Vessels Involved

The characteristics of bleeding often provide clues as to which type of blood vessel has been compromised:

1. Arterial Haemorrhage:Classification by Time or Duration of Haemorrhage

The timing of haemorrhage relative to an injury or surgical procedure provides important diagnostic and prognostic information:

1. Primary Haemorrhage:- Increased intravascular pressure due to actions such as coughing or vomiting.

- Increased venous pressure.

- Physical excitement or administration of stimulant drugs.

- Sepsis: Bacterial infection leading to inflammation and enzymatic destruction of vessel walls.

- Enzymatic Action: For example, the action of pepsin on a bleeding peptic ulcer, eroding the vessel.

- Mechanical Pressure: Persistent pressure from a drainage tube or foreign body (e.g., bone fragment) eroding a vessel.

- Presence of Carcinoma: Malignant tumors can erode blood vessels, leading to chronic or acute bleeding.

Classification by Situation or Location of Haemorrhage

This classification distinguishes whether the blood loss is visible externally or contained within body cavities:

1. External or Revealed Haemorrhage:- Definition: This is bleeding that is directly visible, either from an open wound on the body surface or from a natural body orifice (e.g., epistaxis from the nose, hematemesis from vomiting blood, melena/hematochezia from the rectum).

- Visibility: Blood is immediately apparent and can be quantified relatively easily.

- Definition: This refers to bleeding that occurs into an internal body cavity or tissue space, where the blood loss is not immediately visible externally.

- Locations: Common sites include the peritoneal cavity (e.g., ruptured spleen), pleural cavity (e.g., hemothorax), retroperitoneal space, lumen of hollow organs (e.g., intestines, stomach, bladder), or within the tissues of a limb (e.g., large hematoma).

- Diagnosis: Since the bleeding is concealed, diagnosis relies heavily on the patient's symptoms and signs of hypovolemia and shock. It may be "revealed" later if the blood exits the body (e.g., vomited blood, blood passed per rectum) or by the formation of bruising and swelling on the surface of the body.

Clinical Picture: Signs and Symptoms of Haemorrhage

The clinical presentation of haemorrhage varies depending on the amount, rate, and duration of blood loss. Symptoms and signs reflect the body's compensatory mechanisms attempting to maintain vital organ perfusion, followed by the failure of these mechanisms as blood loss becomes severe. The progression is often categorized into stages of shock.

Early Symptoms and Signs (Compensatory Stage / Class I & II Haemorrhage)

These signs indicate the body's initial attempts to compensate for blood loss (up to 15-30% of blood volume). The sympathetic nervous system is activated.

Neurological/Mental Status:- Restlessness and Anxiety: Often one of the earliest signs, resulting from cerebral hypoperfusion and increased catecholamine release.

- Increased Thirst: Due to fluid shifts and activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system.

- Slightly Increased Pulse Rate (Mild Tachycardia): The heart beats faster to maintain cardiac output despite reduced blood volume.

- Blood Pressure (BP) Maintained or Slightly Lowered: Due to peripheral vasoconstriction attempting to shunt blood to vital organs. Orthostatic hypotension may be present.

- Pallor (Paleness): Due to vasoconstriction and reduced blood flow to the skin.

- Coldness: Skin feels cool to the touch (subnormal temperature, e.g., 36.9°C), also due to peripheral vasoconstriction.

- Slightly Clammy Skin: Due to increased sweating from sympathetic activation.

- Oliguria (Reduced Urine Output): The kidneys conserve fluid and blood flow is shunted away from them.

Symptoms and Signs of Severe Haemorrhage (Decompensatory & Irreversible Stages / Class III & IV Haemorrhage)

These signs manifest when compensatory mechanisms are overwhelmed, and blood loss exceeds 30-40% of total blood volume. This leads to profound organ hypoperfusion and cellular dysfunction.

Neurological/Mental Status:- Lethargy, Drowsiness, Confusion: Progressive worsening of cerebral hypoperfusion.

- Decreased Responsiveness: Leading to stupor and eventually coma.

- Blindness, Tinnitus (Buzzing in the Ears): Severe cerebral ischemia.

- Extreme Pallor: Face becomes ashen white, indicating severe cutaneous vasoconstriction and lack of circulating blood.

- Profound Coldness: Core body temperature may drop significantly (e.g., 36°C or lower), indicating severe hypothermia and circulatory collapse.

- Pulse: Very rapid in rate (severe tachycardia, >120 bpm), thready in volume (barely palpable), and often irregular in rhythm, indicating a severely compromised cardiac output.

- Blood Pressure: Extremely low (severe hypotension), indicating failed compensation and impending circulatory collapse.

- Low Venous Pressure: Due to severely depleted intravascular volume.

- Air Hunger: The patient gasps for breath, with respirations becoming rapid and sighing (Kussmaul-like breathing), as the body attempts to compensate for metabolic acidosis resulting from anaerobic metabolism.

- Dyspnea: Difficult or labored breathing.

- Diminished Urine Volume: Progressing to anuria (no urine production), which may result in acute renal failure due to prolonged renal ischemia.

- Extreme Thirst: Persists and worsens.

- Metabolic Acidosis: Due to widespread anaerobic metabolism and lactic acid accumulation.

- Eventual Multi-Organ Dysfunction Syndrome (MODS): Leading to irreversible organ damage and death.

Management of Haemorrhage: Principles of Care

Effective management of haemorrhage is time-sensitive and aims to stop the bleeding, restore circulating blood volume, optimize tissue perfusion, and treat any underlying coagulopathy.

Immediate Priorities (The "ABCDE" Approach):

- Airway: Ensure a patent airway. If the patient's consciousness is compromised, intubation may be necessary to protect the airway and facilitate ventilation.

- Breathing: Assess respiratory effort and oxygenation. Administer high-flow oxygen (e.g., via non-rebreather mask) to maximize oxygen delivery to tissues. Provide ventilatory support if needed.

- Circulation: This is paramount in haemorrhage.

- Direct Pressure: Apply direct pressure to any visible external bleeding site.

- Large-Bore IV Access: Establish at least two large-bore intravenous (IV) lines for rapid fluid and blood product administration.

- Fluid Resuscitation: Begin rapid infusion of crystalloid solutions (e.g., 0.9% Normal Saline, Lactated Ringer's) while awaiting blood products.

- Blood Transfusion: Initiate blood product transfusion (e.g., packed red blood cells, fresh frozen plasma, platelets) as soon as possible, especially for significant haemorrhage. Consider massive transfusion protocols if appropriate.

- Identify and Stop Bleeding: Promptly identify the source of bleeding and take definitive steps to control it (e.g., surgical intervention, endoscopic intervention, interventional radiology embolization, tourniquet for severe limb trauma).

- Disability (Neurological Status): Assess the patient's level of consciousness (e.g., AVPU scale, GCS) to monitor cerebral perfusion.

- Exposure and Environment: Fully expose the patient to identify all injuries and bleeding sites. Prevent hypothermia by covering the patient with warm blankets, as hypothermia exacerbates coagulopathy.

Ongoing Management and Monitoring:

- Continuous Monitoring: Continuously monitor vital signs (heart rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation), ECG, and urine output. An arterial line may be used for continuous blood pressure monitoring.

- Laboratory Monitoring: Serial blood tests, including complete blood count (CBC), electrolytes, coagulation profile (PT, PTT, fibrinogen), blood type and cross-match, and lactate levels (to assess tissue perfusion and acidosis).

- Temperature Control: Maintain normothermia; hypothermia can worsen coagulopathy and acidosis.

- Correct Coagulopathy: Administer specific clotting factors, cryoprecipitate, or prothrombin complex concentrates (PCCs) as indicated, especially if the patient is on anticoagulants or has a pre-existing coagulopathy. Consider tranexamic acid (TXA) as an antifibrinolytic.

- Pain Management: Administer analgesia cautiously, considering its potential effects on blood pressure and mental status.

- Prevent Complications: Implement strategies to prevent acute kidney injury, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), and multi-organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS).

- Definitive Treatment: Address the underlying cause of the haemorrhage once the patient is stabilized.

Management and Interventions

Effective management of haemorrhage is time-sensitive and requires a multi-faceted approach. The primary goals are to:

- Arrest the haemorrhage: Control and stop the bleeding at its source.

- Restore blood volume: Replenish lost blood and fluids to maintain adequate circulation.

- Manage the extravasated blood: Address the consequences of blood accumulating outside the vessels, and support the body's physiological responses.

I. Arrest of Haemorrhage: Controlling the Bleeding Source

The methods to control bleeding depend on whether the haemorrhage is revealed (external) or concealed (internal).

A. Arrest of Revealed (External) Haemorrhage

Most forms of external haemorrhage can be controlled by applying pressure directly or indirectly to the bleeding site. The choice of method depends on the severity and nature of the bleeding:

Direct Pressure (Pad & Bandage):- Method: This is the simplest, most effective, and often the first line of treatment. Apply a clean, sterile pad directly to the bleeding wound and secure it firmly with a bandage.

- Mechanism: Direct pressure compresses the bleeding vessels, allowing clots to form.

- Advantages: Highly effective, causes minimal damage, and can be performed quickly.

- Method: Fingers are used to apply firm pressure over the pressure point of an artery that supplies the wounded area, proximal to the injury.

- Mechanism: Temporarily occludes the main arterial blood supply to the limb or area.

- Application: Commonly used in areas where direct pressure might be difficult or less effective, such as on the neck (e.g., carotid artery pressure point in severe facial bleeding). It provides temporary control until definitive measures can be taken.

- Method: Raising the injured limb above the level of the heart.

- Mechanism: Reduces hydrostatic pressure in the veins, which can help control venous bleeding.

- Application: A classical method for controlling bleeding from ruptured varicose veins of the leg or other venous injuries.

- Method: A constricting band applied proximally to an injury on a limb. Tourniquets include devices like the Samway anchor, Esmarch’s Elastic bandage, or inflatable cuffs.

- Application: **Use ONLY for the control of heavy, life-threatening bleeding from a limb when other methods have failed or are not feasible.**

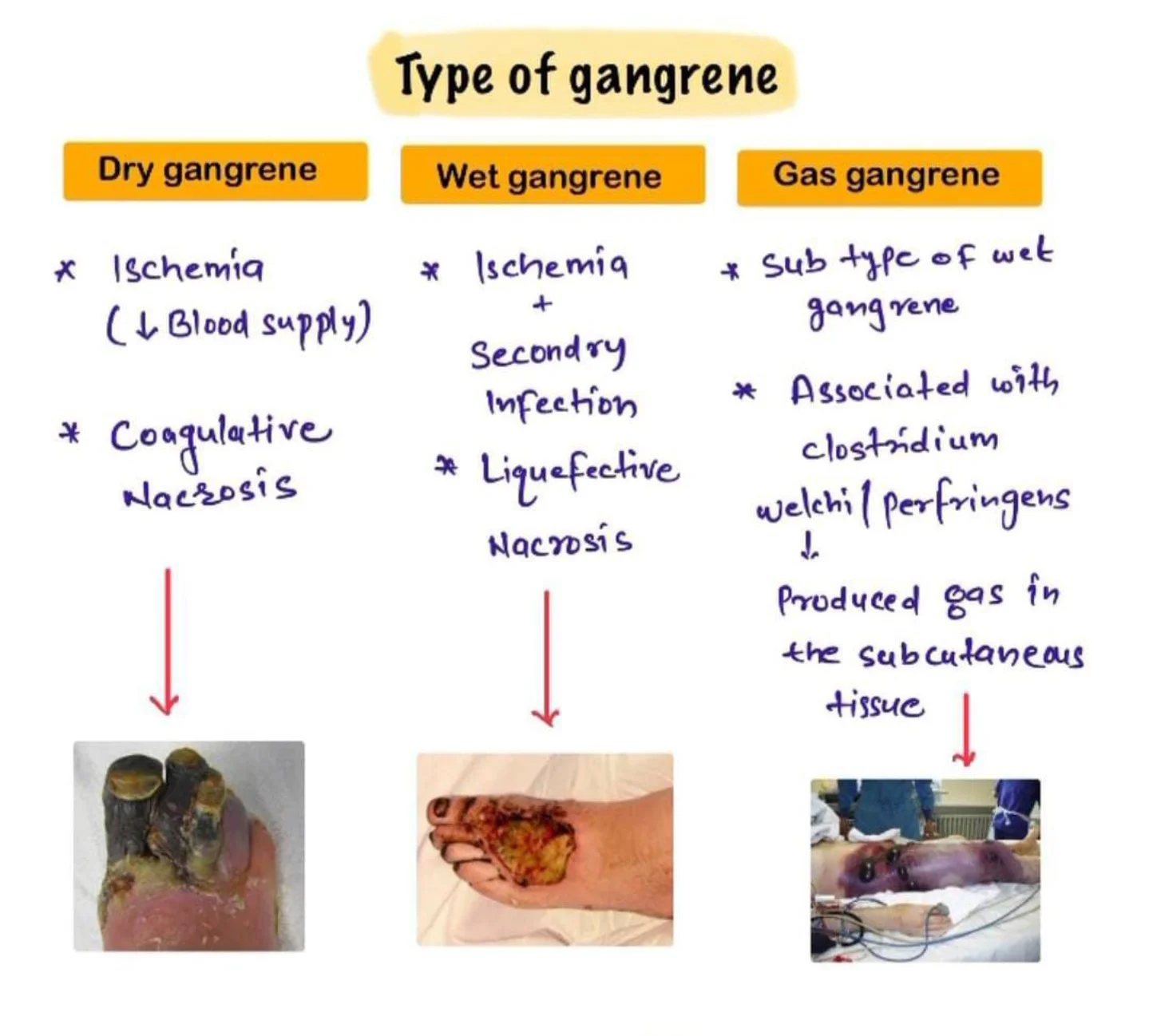

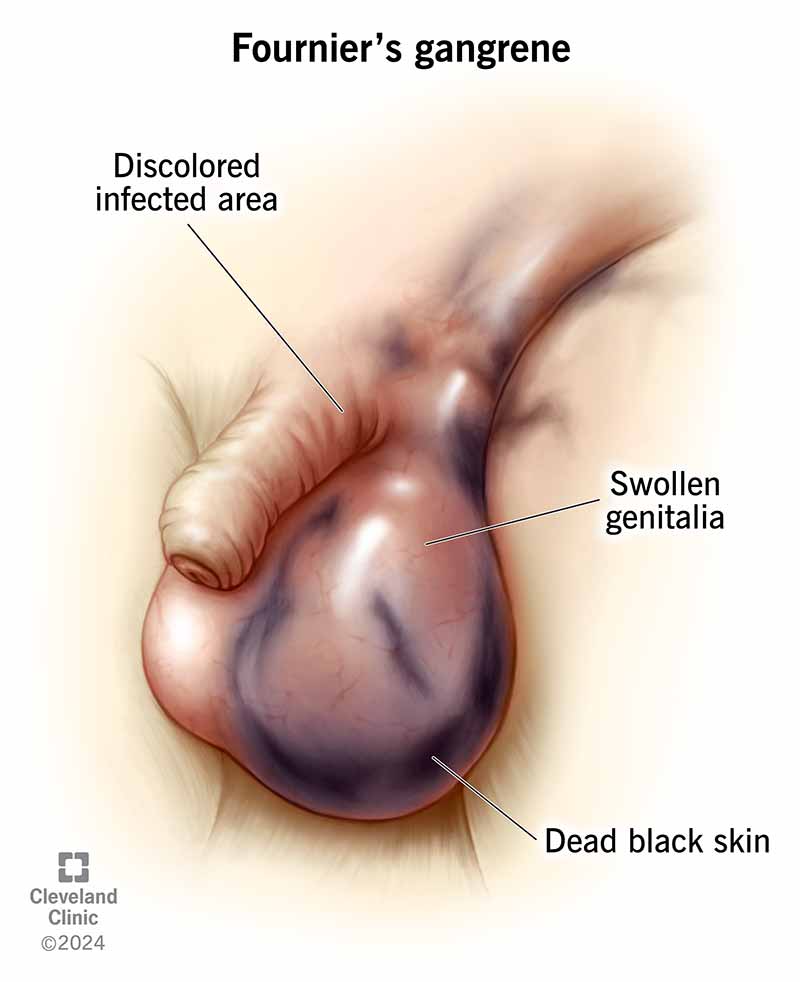

- Dangers: If left on for more than 30 minutes, it carries significant risks such as gangrene, nerve damage, and reperfusion injury upon removal. Requires careful application and monitoring.

- Method: Surgically tying off the bleeding vessel with sutures.

- Application: Necessary if bleeding continues despite less invasive measures or for larger vessels.

- Method: Application of heat (via electrical current) to the bleeding point to seal small vessels.

- Application: Commonly used in surgical settings for precise haemostasis.

- Method: Deliberate occlusion of bleeding blood vessels by introducing embolic materials (e.g., coils, particles, glues) through an angiographic catheter under imaging guidance.

- Application: Common in controlling bleeding from internal sources like oesophageal varices, gastric ulcers, or arterial bleeds in inaccessible locations. Examples of emboli include lyophilized human dura mater.

- Method: Insertion of sterile gauze or specialized hemostatic dressings into a wound or cavity to apply internal pressure.

- Application: A temporary measure for very severe bleeding, often used in theatre to control sudden haemorrhage or for diffuse bleeding that is difficult to ligate.

- Method: Substances capable of causing bleeding to stop when applied locally.

- Examples: Include topical thrombin, collagen, gelatin sponges, oxidized regenerated cellulose (Oxycel). Some natural substances like snake venom or adrenaline can also act as styptics.

- Application: Used locally in certain cases for low-pressure bleeding from capillaries and venules.

B. Arrest of Concealed (Internal) Haemorrhage

Controlling internal haemorrhage is more challenging as direct pressure is often not possible. Management focuses on internal pressure, addressing the underlying cause, and enhancing coagulation.

Surgical Ligation/Repair:- Method: Direct surgical intervention to identify and ligate or repair the bleeding vessel.

- Application: Often the definitive treatment for ruptured organs (e.g., ruptured spleen, liver laceration) or major vessel injuries.

- Method: Removing blood clots from a hollow organ can allow it to contract and seal bleeding vessels.

- Application: For severe bleeding from the bladder, passing a catheter and emptying it of clots can help the bladder contract and tamponade bleeding.

- Method: Administration of medications that promote vasoconstriction.

- Examples:

- Adrenaline (Epinephrine): Can be added to saline or sodium bicarbonate for washing out an organ to encourage vessel constriction (e.g., in some urological procedures, often done two-hourly).

- Ergometrine: Used post-partum to stimulate uterine contractions and reduce bleeding after the birth of the placenta.

- Vasopressin (Pitressin): Can be used effectively in the control of bleeding from oesophageal varices by causing splanchnic vasoconstriction.

- Method: Administering agents that correct clotting factor deficiencies.

- Application: Very valuable when the mechanism of clotting is deficient.

- Vitamin K (IM): Important in jaundiced patients or those with liver dysfunction who are bleeding due to impaired synthesis of Vitamin K-dependent clotting factors.

- Factor VIII Concentrate: Indicated in patients with Haemophilia A.

- Fresh Frozen Plasma (FFP), Platelets, Cryoprecipitate: Administered to provide clotting factors or platelets as needed.

- Method: Using specialized materials to provide internal pressure or promote clotting.

- Examples:

- Gauze soaked in adrenaline can be effective in certain sites (e.g., nasal packing for epistaxis).

- Oxycel (oxidized regenerated cellulose), Fibrin glue, or a piece of the patient’s own crushed muscle can be used to promote local haemostasis in surgical beds.

- Method: Systemic antibiotic administration.

- Application: Essential in secondary haemorrhage, especially when caused by infection, to control sepsis which contributes to vessel wall breakdown.

- Method: Applying pressure from within a lumen using an inflatable balloon.

- Application: Applied by the balloon of a triluminal tube (e.g., Sengstaken-Blakemore tube) in bleeding oesophageal varices or by the balloon of a Foley catheter in a post-prostatectomy cavity.

- Method: Use of medications that inhibit the breakdown of blood clots.

- Example: Achieved by the use of Tranexamic Acid (TXA), which stabilizes clots and reduces bleeding in various conditions.

II. Restoration of Blood Volume and Oxygen Carrying Capacity

Replacing lost fluid and blood is crucial to maintain adequate circulation and tissue perfusion.

- Airway: Ensure a patent airway. Intubation may be necessary if consciousness is compromised to protect the airway and facilitate ventilation.

- Breathing: Assess respiratory effort and oxygenation. Administer high-flow oxygen (e.g., via non-rebreather mask) to maximize oxygen delivery to tissues. Provide ventilatory support if needed.

- Circulation: This is paramount.

- Large-Bore IV Access: Establish at least two large-bore intravenous (IV) lines (e.g., 14-16 gauge) for rapid fluid and blood product administration. Central venous access may be needed in severe cases.

- Fluid Resuscitation: Begin rapid infusion of crystalloid solutions (e.g., 0.9% Normal Saline, Lactated Ringer's) as initial volume expanders while awaiting blood products. Monitor response.

- Blood Transfusion: Initiate blood product transfusion (e.g., packed red blood cells to increase oxygen-carrying capacity; fresh frozen plasma for clotting factors; platelets for thrombocytopenia) as soon as possible, especially for significant haemorrhage. Consider massive transfusion protocols (MTP) for severe, ongoing bleeding.

- Disability (Neurological Status): Assess the patient's level of consciousness (e.g., AVPU scale, GCS) to monitor cerebral perfusion and detect neurological changes.

- Exposure and Environment: Fully expose the patient to identify all injuries and bleeding sites. Prevent hypothermia by covering the patient with warm blankets, as hypothermia significantly exacerbates coagulopathy and metabolic acidosis.

- Continuous Monitoring: Continuously monitor vital signs (heart rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation), ECG for cardiac rhythm, and hourly urine output via an indwelling urinary catheter (a sensitive indicator of renal perfusion). An arterial line provides continuous and accurate blood pressure monitoring.

- Laboratory Monitoring: Frequent serial blood tests are essential:

- Complete Blood Count (CBC): To monitor hemoglobin and hematocrit.

- Electrolytes and Renal Function Tests: To assess fluid and electrolyte balance and kidney function.

- Coagulation Profile: PT, PTT, fibrinogen to assess clotting status.

- Blood Type and Cross-match: For blood product compatibility.

- Lactate Levels: To assess tissue perfusion and severity of acidosis.

- Arterial Blood Gases (ABGs): For oxygenation, ventilation, and acid-base balance.

- Temperature Control: Actively maintain normothermia using warming blankets and warmed fluids.

- Correct Coagulopathy: Actively manage any identified clotting factor deficiencies by administering specific factor concentrates, cryoprecipitate, or prothrombin complex concentrates (PCCs), especially if the patient is on anticoagulants or has a pre-existing coagulopathy.

A. Nursing Diagnoses for Patients with Haemorrhage (Examples)

Nursing diagnoses are clinical judgments about individual, family, or community responses to actual or potential health problems/life processes. For haemorrhage, they often focus on perfusion, fluid balance, and anxiety.

- Deficient Fluid Volume related to active blood loss, as evidenced by hypotension, tachycardia, decreased urine output, cool/clammy skin, and altered mental status.

- Ineffective Tissue Perfusion (specify: Cerebral, Cardiopulmonary, Renal, Gastrointestinal, Peripheral) related to hypovolemia and decreased oxygen-carrying capacity, as evidenced by altered mental status, oliguria, delayed capillary refill, weak pulses, or abnormal ABGs.

- Decreased Cardiac Output related to reduced preload (due to blood loss), as evidenced by hypotension, tachycardia, and signs of hypoperfusion.

- Risk for Shock related to uncompensated blood loss.

- Anxiety/Fear related to threat to health status, perceived loss of control, and critical illness.

- Risk for Imbalanced Body Temperature (Hypothermia) related to hypovolemia, decreased metabolic rate, and rapid fluid resuscitation.

- Acute Pain related to injury or invasive procedures, as evidenced by patient report, guarding behavior, or vital sign changes.

B. Nursing Interventions for Haemorrhage

Nursing interventions are actions designed to achieve patient outcomes related to the nursing diagnoses. These are broad categories and require specific adaptation based on the individual patient's condition and the type of haemorrhage.

- Prioritize ABCs and Rapid Response:

- Immediately assess and maintain airway patency, breathing effectiveness, and circulation.

- Activate rapid response team/code team according to facility protocol for acute haemorrhage.

- Stay with the patient; do not leave an acutely bleeding patient unattended.

- Control Bleeding (Nursing Actions):

- Apply direct, firm pressure to any external bleeding site using sterile dressings. Elevate the affected limb if appropriate.

- Prepare and assist with tourniquet application if indicated for life-threatening limb haemorrhage (monitor time).

- Prepare for and assist with surgical or interventional radiology procedures for definitive bleeding control.

- Ensure all lines, drains, and tubes are securely in place to prevent accidental dislodgement.

- Fluid and Blood Volume Resuscitation:

- Establish and maintain multiple large-bore IV access sites.

- Administer prescribed IV fluids (crystalloids) and blood products (PRBCs, FFP, platelets) rapidly, using rapid infusers if available, and monitor patient response.

- Monitor for signs of fluid overload or transfusion reactions.

- Ensure warmed fluids and blood products are used to prevent hypothermia.

- Continuous Assessment and Monitoring:

- Monitor vital signs (BP, HR, RR, SpO2, Temp) continuously (e.g., every 5-15 minutes or more frequently in acute phase).

- Assess level of consciousness (LOC) and neurological status frequently for signs of cerebral hypoperfusion.

- Monitor hourly urine output via indwelling catheter; report output less than 0.5 mL/kg/hour.

- Assess skin color, temperature, and capillary refill for signs of peripheral perfusion.

- Monitor dressing for increasing saturation and measure blood loss (e.g., weigh pads, assess drainage in collection devices).

- Review and trend laboratory results (Hgb, Hct, lactate, coagulation studies, electrolytes).

- Assess for signs of internal bleeding if concealed haemorrhage is suspected (e.g., increasing abdominal girth, distension, pain, bruising, changes in bowel sounds, persistent hypotension despite fluid resuscitation).

- Oxygenation and Respiratory Support:

- Administer oxygen as prescribed to maintain SpO2 >94%.

- Monitor respiratory effort and patterns; prepare for ventilatory support if respiratory distress or failure occurs.

- Maintain Normothermia:

- Use warming blankets, warmed IV fluids, and control room temperature to prevent and treat hypothermia.

- Pain and Anxiety Management:

- Administer analgesics as prescribed, carefully monitoring for effects on vital signs.

- Provide emotional support, calm reassurance, and clear, concise explanations to the patient and family. Address their fears and anxiety.

- Create a calm environment as much as possible.

- Prevent Complications:

- Maintain strict asepsis for all invasive procedures (IV insertion, catheter care) to prevent infection.

- Implement measures to prevent pressure injuries due to immobility and hypoperfusion.

- Initiate DVT prophylaxis as soon as appropriate and ordered.

- Monitor for signs of acute kidney injury or multi-organ dysfunction.

- Documentation and Communication:

- Accurately and timely document all assessments, interventions, and patient responses.

- Communicate effectively and frequently with the interdisciplinary team (physicians, respiratory therapists, lab, blood bank) regarding patient status and changes.

- Handover critical information thoroughly.

Special Types and Terms of Haemorrhage

Haemorrhage can manifest in various specific ways depending on its anatomical location, and certain terms are used to describe these particular presentations.

Specific Types of Haemorrhage

These are haemorrhages that are identified by their site of external manifestation or unique characteristics:

Epistaxis (Nosebleed):- Description: Bleeding from the nose.

- Common Causes:

- Injury to the nose (trauma).

- Fracture base of the skull (indicating severe trauma).

- Ulceration of the mucus membrane of the nose (e.g., from dryness, digital manipulation).

- Bleeding disorders (e.g., leukemia, haemophilia).

- Local infections like rhinitis.

- Venous congestion associated with heart diseases (e.g., heart failure).

- Hypertension (high blood pressure).

- Management:

- Initial First Aid: The patient should sit upright, leaning slightly forward (not backward, to prevent blood from flowing down the throat), and firm pressure should be applied to the soft cartilaginous part of the nostrils for 10-15 minutes.

- Sponge the face with cold water or apply a cold compress to the bridge of the nose.

- If bleeding persists, medical attention is required.

- Medical Interventions:

- The nose may be packed with sterile gauze, sometimes impregnated with vasoconstrictors like adrenaline, or specialized nasal packing devices.

- The nasal plug/pack is typically left in situ for 24-48 hours, with careful monitoring due to the risk of infection (sepsis) and potential airway obstruction.

- Recurrent or persistent bleeding may be treated by chemical (e.g., silver nitrate) or electrical (electrocautery) cauterization of the bleeding vessel.

- In severe cases, surgical ligation of feeding arteries or interventional radiology embolization may be necessary.

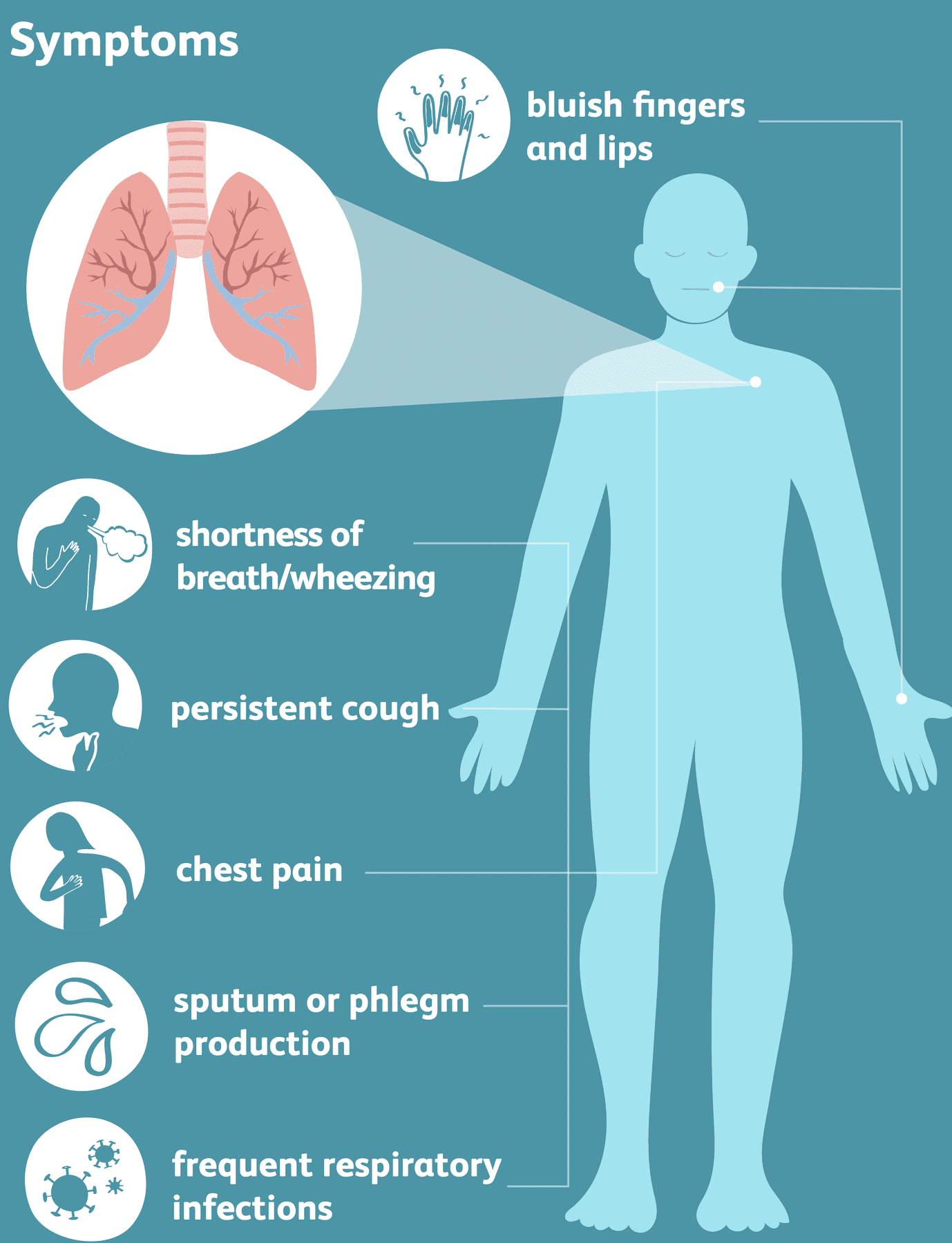

- Description: This is the coughing up of blood from the respiratory tract (lungs or bronchial tubes). The blood is typically bright red, frothy (mixed with air), and alkaline. It is often mixed with sputum.

- Common Causes:

- Pulmonary diseases (e.g., Tuberculosis (TB), Bronchiectasis, Pneumonia, Lung abscess).

- Lung cancer (bronchogenic carcinoma).

- Benign tumours of the respiratory tract.

- Injury to the lungs or chest (trauma).

- Pulmonary embolism (especially with infarction).

- Venous congestion into the lungs (e.g., severe heart failure, mitral stenosis).

- Blood disorders (e.g., leukemia, coagulopathies).

- Rupture of an aortic aneurysm into a bronchus (rare but life-threatening).

- Foreign body aspiration.

- Management:

- Immediate Action: Severe cases require urgent medical assessment and treatment to secure the airway and control bleeding.

- Patient Care:

- Maintain a calm environment and reassure the patient (care of the mind).

- Position the patient sitting up to aid breathing and prevent aspiration; usually, the bleeding side down if known, to protect the contralateral lung.

- Ensure total rest.

- Frequent mouth washes to remove the taste of blood.

- Provide non-stimulating fluids.

- Keep the patient warm.

- Medical Interventions:

- Collect blood for Hemoglobin (HB) estimation, blood grouping, and cross-matching for potential transfusion.

- Blood transfusion if bleeding is severe and causing hemodynamic instability.

- Administer antitussives (e.g., codeine, morphine) to suppress cough, which can exacerbate bleeding, and to provide sedation.

- Treat the underlying cause (e.g., antibiotics for infection, chemotherapy/radiation for cancer, bronchoscopic intervention).

- Bronchoscopy for localization and intervention (e.g., laser coagulation, balloon tamponade).

- In severe cases, surgical resection may be considered.

- Description: This is vomiting blood from the upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract (esophagus, stomach, or duodenum). The blood may be bright red (indicating active, fresh bleeding) but is more often brown, resembling "coffee grounds" due to the action of gastric acid on hemoglobin. It is acidic.

- Common Causes:

- Peptic ulcers (gastric or duodenal ulcers).

- Acute gastritis (inflammation of the stomach lining, often due to corrosive drugs like NSAIDs/Aspirin, or alcohol taken on an empty stomach).

- Gastric cancer.

- Oesophageal varices (dilated veins in the esophagus, often due to portal hypertension, e.g., in liver cirrhosis).

- Mallory-Weiss tear (tear in the esophageal lining due to forceful vomiting/retching).

- Swallowed blood (e.g., after severe epistaxis or haemoptysis).

- Fracture base of the skull (blood from nasopharynx tracking down).

- Post-operative bleeding after nose and throat surgeries.

- Blood disorders (e.g., leukemia, coagulopathies).

- Management:

- Initial Assessment: Immediate assessment of hemodynamic stability.

- Investigations:

- Collect blood for HB, grouping, and cross-matching.

- Stool for occult blood test.

- Patient Care:

- Ensure absolute rest and quietness.

- Frequent monitoring of vital signs.

- Provide emotional support.

- Medical Interventions:

- Fluid resuscitation and blood transfusion if indicated.

- Administer morphine for pain and sedation as needed, while carefully monitoring respiratory status and vital signs.

- Specific Treatment According to Cause:

- Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) for ulcers/gastritis.

- Endoscopic intervention (e.g., banding, sclerotherapy for varices; clipping, coagulation for ulcers).

- Surgical intervention for refractory cases or severe bleeds not amenable to endoscopy.

- General nursing care including NPO (nothing by mouth) and monitoring for further bleeding.

- Description: This is the passage of dark, tarry, sticky stools (faeces) with a characteristic foul odor. It results from bleeding in the upper GI tract, where blood has been digested and altered by intestinal bacteria. Usually indicates bleeding from a site high in the GIT (esophagus, stomach, duodenum, or small bowel).

- Common Causes:

- Duodenal ulcers (most common cause).

- Gastric ulcers.

- Gastritis.

- Bleeding from the small bowel.

- Swallowing of a large amount of blood (e.g., from severe epistaxis or haemoptysis).

- Certain medications like iron supplements (can cause dark stools, but not true melaena, which is positive for occult blood) or bismuth subsalicylate.

- Investigation: Stool for occult blood (guaiac test) confirms the presence of blood. Endoscopy is usually required to identify the source.

- Management: As for internal haemorrhage, focusing on hemodynamic stabilization, identifying the source, and definitive treatment (often endoscopic or medical).

- Description: Is the passage of blood in urine, making it appear pink, red, or dark brown/cola-colored. It can be macroscopic (visible to the naked eye) or microscopic (detectable only with urinalysis).

- Common Causes:

- Trauma to the urinary tract (e.g., ruptured kidney, bladder injury).

- Urinary tract infections (UTIs).

- Renal calculi (kidney stones) – often associated with pain.

- Chronic kidney infection (pyelonephritis).

- Tuberculosis (TB) of the kidney.

- Post-operative causes (e.g., prostatectomy, bladder surgery).

- Growths/tumours in the bladder, kidney, or prostate (can be painless haematuria, requiring urgent investigation).

- Leukemia or other blood disorders affecting clotting.

- Inflammation of the urinary tract (e.g., cystitis, glomerulonephritis, bilharzia/schistosomiasis).

- Certain medications (e.g., anticoagulants).

- Management:

- Less Severe Cases: Rest in bed and reassurance, along with treatment of the underlying cause.

- More Severe Cases: If there's significant damage to the bladder or kidneys, or a mass, surgical intervention (e.g., to remove stones, excise tumors, repair trauma) may be indicated.

- Specific treatment varies significantly according to the underlying cause. This may include antibiotics for infection, medical management for kidney disease, or interventional procedures for stones/tumors.

Special Terms for Haemorrhage from Specific Sites/Contexts

These terms describe the location of blood accumulation or specific bleeding patterns:

- Haemothorax: Bleeding into the pleural cavity (space between the lungs and the chest wall). Often due to chest trauma or lung pathology.

- Haemoperitoneum: Bleeding into the peritoneal cavity (abdominal cavity). Often associated with ruptured organs (e.g., spleen, liver) or major vessel injury.

- Haemarthrosis: Bleeding into a joint space. Common in individuals with bleeding disorders like haemophilia or following trauma.

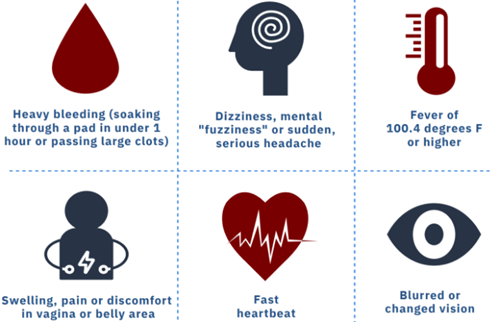

- Menorrhagia: Excessive or prolonged menstrual bleeding at regular intervals.

- Metrorrhagia: Irregular, acyclic uterine bleeding occurring between expected menstrual periods.

- Menometrorrhagia: Prolonged or excessive bleeding occurring at irregular and frequent intervals.

- Haemopericardium: Bleeding into the pericardial sac (the sac surrounding the heart). Can lead to cardiac tamponade, a life-threatening condition.

- Haematomyelia: Bleeding into the spinal cord parenchyma.

- Haematoma: A localized collection of extravasated blood, usually clotted, in an organ, space, or tissue (e.g., a bruise).

- Ecchymosis: A discoloration of the skin resulting from bleeding underneath, typically caused by bruising. Larger than petechiae.

- Petechiae: Small (1-2 mm), pinpoint, non-blanching red or purple spots on the skin caused by minor hemorrhage.

- Purpura: Red or purple discolored spots on the skin that do not blanch on pressure, caused by bleeding underneath the skin. Larger than petechiae but smaller than ecchymoses.

HAEMORRHAGE: Nursing Lecture Notes Read More »

BURNS LECTURE NOTES

BURNS

Burns are injuries to the skin due to extremes of temperature i.e cold or hot, chemicals or radiations. Burns occur when there is injury to the tissues of the body caused by heat, chemicals, electric current or radiations.

Anatomical review of the skin.

- Skin is the largest organ of the body that protects against injury, loss of fluid and from infection.

- It also maintains a constant body temperature with sebum, hair follicles. The skin has got two layers;

- -Epidermis (outer layer) and -Dermis (inner layer).

- Under the skin is sebaceous tissue mainly fat.

- The top part of the skin (epidermis) is made up of fat cells which are constantly shed and are replaced by new cells which come from underneath the layer.

- The epidermis has got an oily layer called sebum produced by sebaceous gland. It prevents heat loss (it thickens when it’s cold).

- Sebum makes the skin water proof, makes skin supplies plethoric.

- The dermis contains blood vessels, nerve, muscles, sweat glands, hair follicles, sebaceous glands; the ends of the sensory nerves in the dermis register sensation from the body surface.

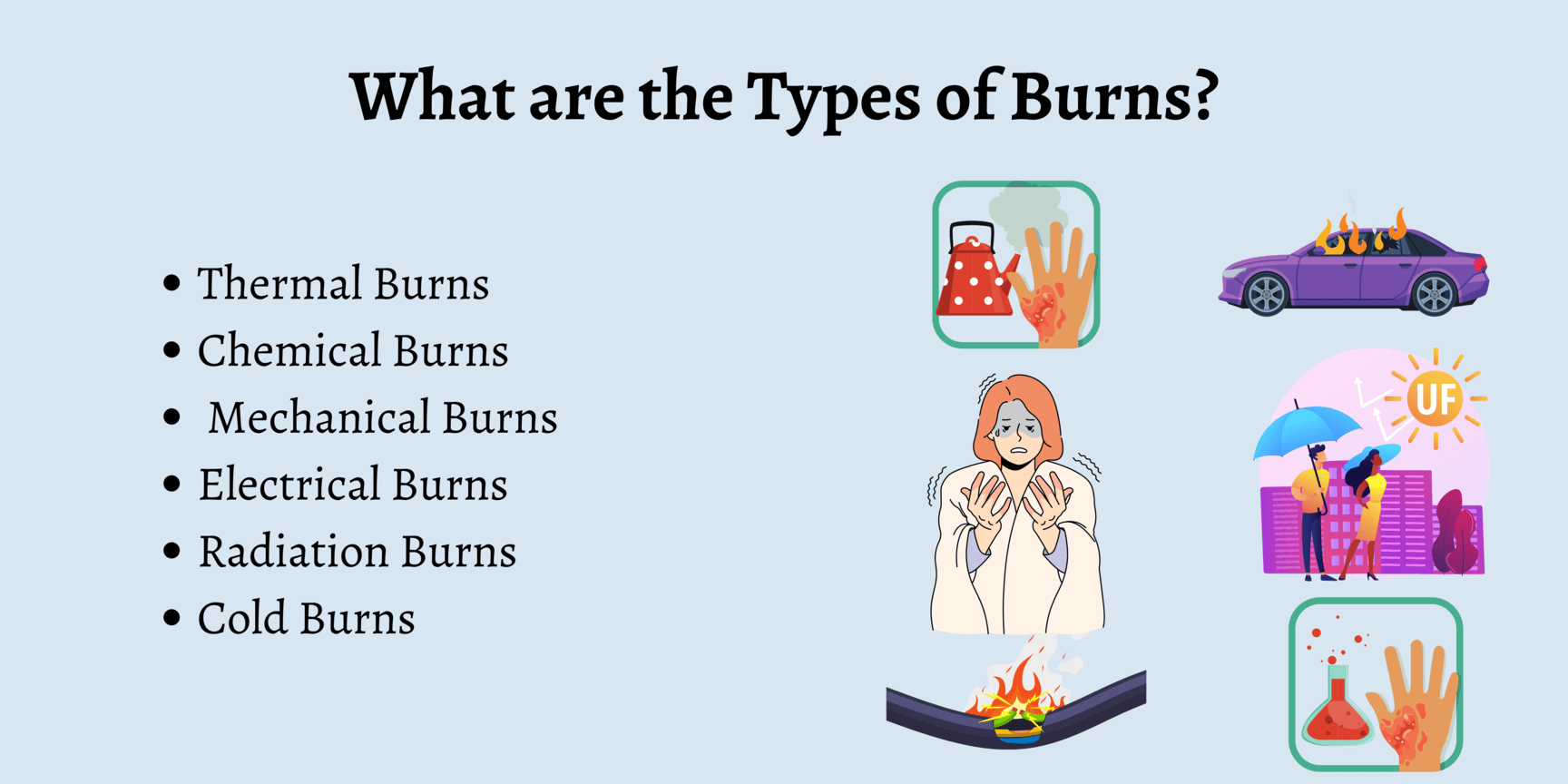

TYPES OF BURNS

Thermal burns

These can be caused by flame, flash, scald, or contact with hot object.

Chemical burns

These are the result of tissue injury and destruction from necrotizing substance. Chemical burns are most commonly caused by acids; however alkalis can also cause a burn e.g. cleaning agents, drain cleaners and lye’s.

Electrical burns

These result from coagulation necrosis that is caused by intense heat generated from an electrical current. It can also result from direct damage to nerves and vessels causing tissue anoxia and death. The severity of the electrical injury depends on the amount of voltage, tissue resistance, current pathways, and surface area in contact with the current and on the length of time the current flow was sustained.

Smoke and inhalation injury

It results from inhalation of hot air or noxious chemicals that can cause damage to the tissues of the respiratory tract. Smoke inhalation injuries are an important determinant of motility in the fire victims.

- Carbon monoxide poisoning.

- Inhalation injury above the glottis, it is thermally produced and above is chemically produced.

- Inhalation injury below the glottis is related to the length of exposure to smoke or toxic fumes.

Cold thermal injury

These are due to extreme cold temperatures e.g. frost bite, freezing metals.

Irradiations

I.e. sun burn, radiation therapy, medical therapy e.g. treatment of cancer of the cervix.

SCALDS

Are injuries caused by moist heat, and hot liquids?

CLASSIFICATION OF BURN INJURY

Burns are classified according to;

- Depth of the burn.

- Extent of the burn.

- Location of the burn.

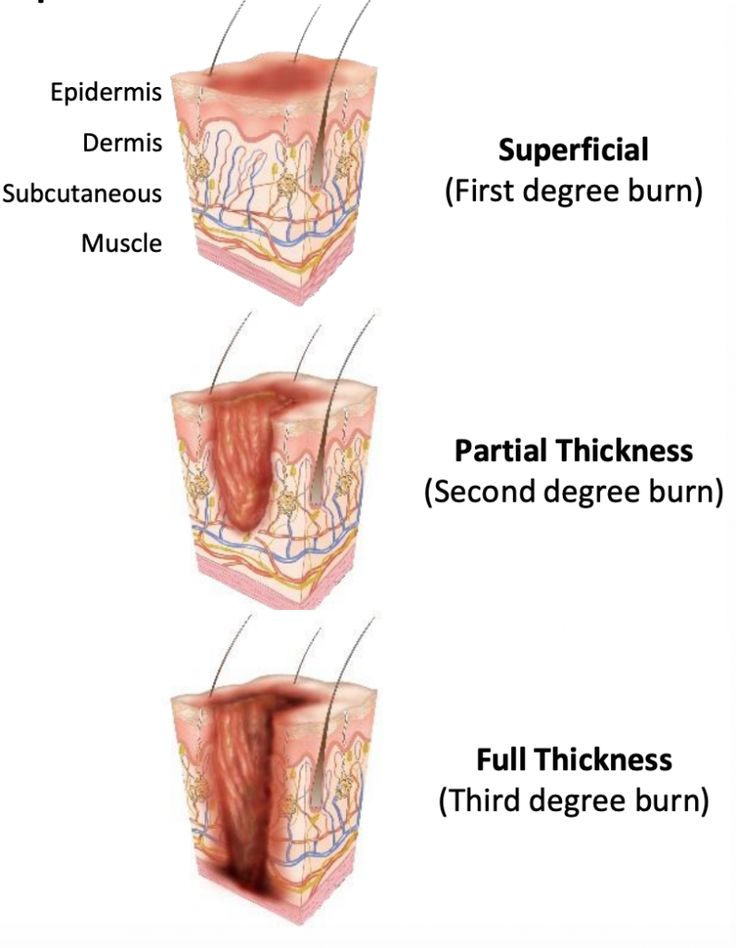

DEPTH OF THE BURN

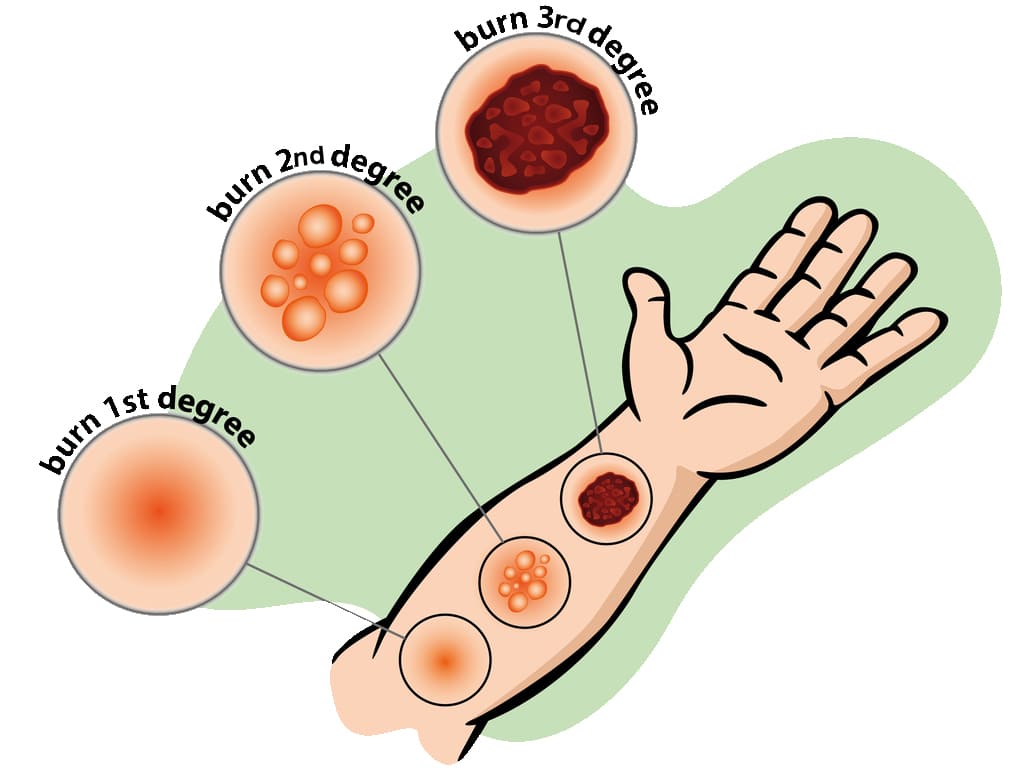

In the past, burns were defined by degrees; first degree, second degree and third degree burns. They now advocate more explicit definition categorizing the burn according to the depth of skin destruction.

- SUPERFICIAL BURNS: Involves only the outer most skin layer. They have redness, swelling, and tenderness. It usually heals well, if first aid is given promptly and if blisters don’t form. Burns from sun, charcoal stove. Are also known as first degree burns.

- PARTIAL THICKNESS BURNS: The damage to epidermis is severe, we almost always have blister formation and very painful. Completely destroys the epidermis. Blisters form because of fluid released from the damaged tissue, usually heal well but may be fatal if more than 30% of skin is involved. Also known as second degree burns.

- FULL THICKNESS/DEEP BURNS: The dermis is involved including other structures like muscles, bones. All layers involved blood vessels, fat and nerves. There is either no pain or minimal. This may mislead that the burns are not severe. You need immediate help; the skin is pale and charred (like toasted meat).

LOCATION OF BURN

- The location of the burn wound is related to the severity of the burn injury. Burns to the face and neck and circumferential burns of the chest may inhibit respiratory function by virtue of mechanical obstruction secondary to edema or scar formation.

- These injuries may also indicate the possibility of inhalation injury and respiratory mucosal damage.

- Burns of the hands, feet, joints, and eyes are of concern because they make self-care very difficult and may jeopardize future function.

- The ears and nose, composed mainly of cartilage, are susceptible to infection because of poor blood supply to the cartilage.

- Burns of buttocks and genitalia are highly susceptible to infection.

- Circumferential burns of the extremities can cause circulatory compromise distal to the burn with subsequent neurologic impairment of the affected extremity.

- Patient may develop compartment syndrome from direct heat damage to the muscles, multiple intravenous access attempts or pre burn vascular problems.

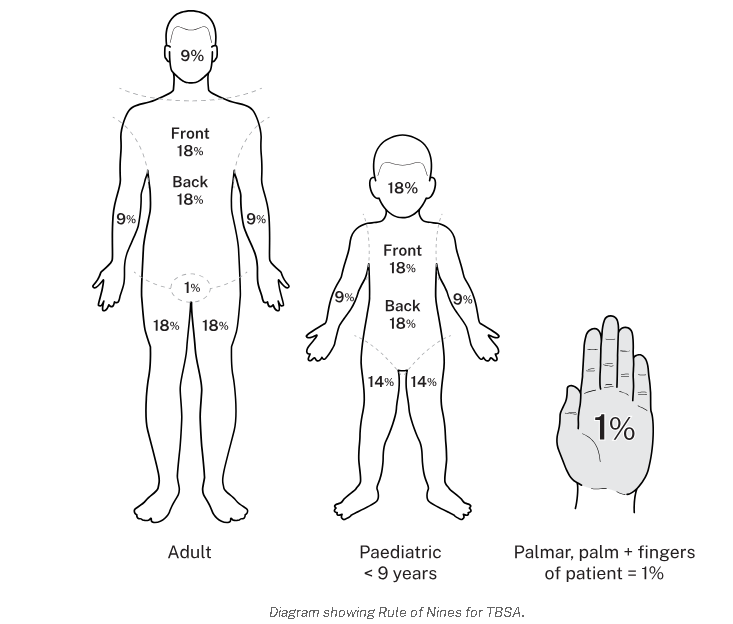

EXTENT OF A BURNT AREA.

Two commonly used guides for determining the total body surface area (TBSA) affected or the extent of a burn wound are the Lund-Browder chart and rule of nines. Only partial thickness burns and full thickness burns are included when calculating the burnt area because it is more accurate. The patient’s age, in proportions to relative body area size, is taken into account. For irregular or odd-shaped burns, the palmar surface of the patient’s hand is considered to be approximately 1% of the TBSA.

USES OF WALLACE’S RULE OF 9 (for Adults)

- Head and neck is 9% (NB. The head alone is 8% and the neck is 1%).

- Each arm is 9% (both arms carry 18%).

- Anterior trunk-18% (chest and abdomen).

- Posterior trunk-18% (from neck to symphysis, coccyx).

- Each lower limb-18% (both limbs 36%).

- Perineal/genital area-1%.

WALLACE’S RULE IN CHILDREN (slight difference)

- Head -18%

- Arms -9%

- Chest and trunk -18%

- Back of trunk -18%

- Legs -14%

- Perineal and genital area -1%

Use of Lund Browder’s chart

| Head | 7% |

| Neck | 2% |

| Anterior trunk | 13% |

| Posterior trunk | 13% |

| Rt buttock | 2.5% |

| Lt buttock | 2.5% |

| Genitalia | 1% |

| Rt upper arm | 4% |

| Lt upper arm | 4% |

| Rt lower arm | 3% |

| Lt lower arm | 3% |

| Rt hand | 2.5% |

| Lt hand | 2.5% |

| Rt thigh | 9.5% |

| Lt thigh | 9.5% |

| Rt leg | 7% |

| Lt leg | 7% |

| Rt foot | 3.5% |

| Lt foot | 3.5% |

| Total | 100% |

PREDISPOSING FACTORS & ASSESSMENT

PREDISPOSING FACTORS

- Age, children and old (weak)

- Disease-commonly epilepsy, leprosy

- alcoholism, and cigarette smoking

- Occupation-e.g. electricians, industrial workers, alcohol brewers

- Poverty e.g crowded kitchen.

- Fights (wrangles and conflicts)

- Race e.g. frost bite common in whites

- Skin bleaching.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS OF BURNS

- History of involvement with any of the cause of burns.

- Blistering due to vasodilation hence collection of serum between the dermis and epidermis.

- Necrosis due to coagulation of proteins.

- Functional impairment of the temperature regulation process of the burnt area.

- Shock due to fluid loss and blood loss (hypovoleamic shock).

- Shock can also occur due to severe pain (neurogenic shock).

- Toxaemia depending on the type and cause of burns. Histamines and adenocytes produced are released from the burnt surface and they find their way into the blood stream.

ASSESSMENT OF BURNS

- Circumstances and cause of burns i.e. where and when did it occur.

- Was the airway affected? Assess whether it was in closed spaces (inhaled hot gases).

- Assess the extent, location and depth. The bigger the burn, the higher the extent (%) the greater the surface area.

CRITERIA FOR ADMISSION OF BURNT PATIENT.

- Burns involving the airways

- Full thickness.

- Admit all children for observation

- The bigger the surface area above 5% superficial burns.

- Special areas involved e.g. face, hands, joints, neck, and genitalia.

- Circumferential burns give a tourniquet effect may cause gangrene.

- Electric burns because all electric burns are said to be deep until proved otherwise.

- Chemical burns, can continue burning for several days.

- If you are not sure; below 15% burns, GIT absorption is intact, oral route work in fluid replacement.

FIRST AID FOR BURNS.

AIMS

- Maintain an open airway.

- Minimize the risk of infection

- Treat any other associated injuries

- Make sure you watch for signs of shock.

- Make sure you check for signs of respiratory distress.

ACHIEVING THE FIRST AID MANAGEMENT

- Decrease temperature /stop fire if possible.

- Call for help.

- Evacuate the patient; pour water on the affected area.

- Undress the patient.

- Assume the airway has been affected until proved otherwise continue pouring water on the burnt area for minimally 20min to reduce injury i.e neutralized heat.

- Lie patient down but avoid the burnt area touching the ground.

- Pour water on burns for 20mins.

- Continue pouring water until pain stops.

- Put on gloves.

- Remove rings, shoes, watches, necklace, belts, stockings and clothes before tissue damage.

- Cover the injured area with sterile cloth or sterile dressing.

- Record details of injuries.

- Regularly monitor and record the vital signs and the level of consciousness, urine output.

- Treat shock if present.

- Re-assure and give words of hope.

- Avoid over cooling the patients especially children and elderly because they may get hypothermia.

- Do not remove anything stuck on the burnt wound to prevent spread of infections and more injuries.

- Do not touch the burnt area with your fingers.

- Do not apply lotions on the burn apart from anti-septic.

- Do not burst any blisters.

- If burns are on the face do not cover them for easy assessment of respiratory distress.

FOR AIRWAY BURNS

Burns of the face, mouth, throat, nose, airway passages, are serious because the airway passage rapidly becomes swollen because of inflammation.

How to assess for airway burns.

- History taking.

- Respiratory rate increased.

- Examine the nostrils i.e there is no soot.

- Examine the nasal hair i.e if they are burnt, short with a Taft.

- There would be damaged to the skin around the nose and mouth.

- Has difficulty in breathing.

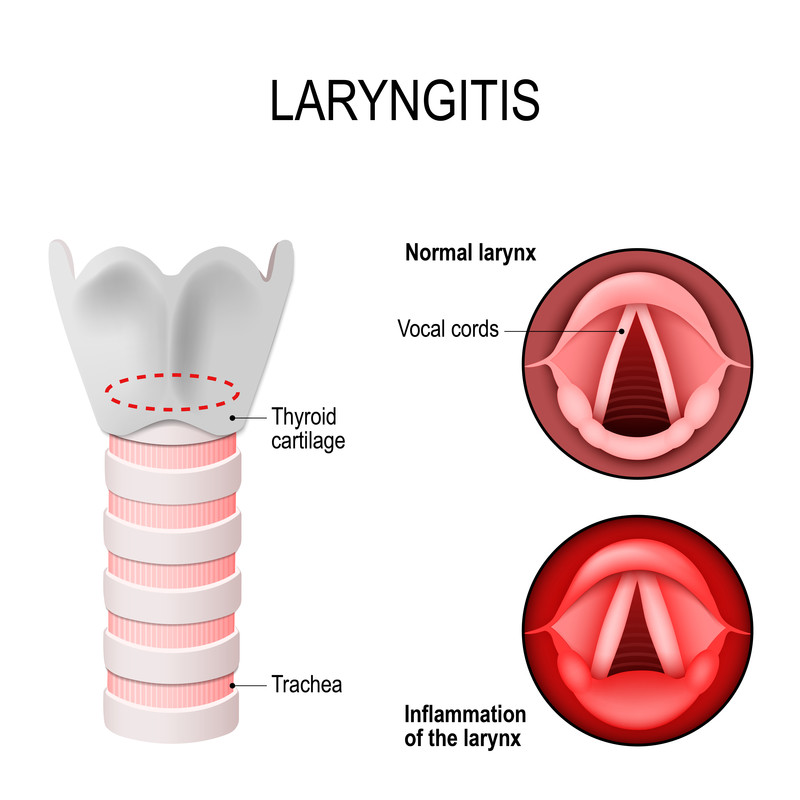

- Has hoarse voice due to inflammation of vocal cords.

AIMS OF MANAGEMENT

- To recognize the airway burns.

- To maintain the airway and after take the patient to hospital management.

First Aid Management for Airway Burns

- Open the mouth (airway) and check whether he is breathing.

- Sweep the tongue.

- If not breathing, give rescue breaths, mouth to mouth. Put patient in a recovery position and call for help.

- Take the steps to improve the airway e.g remove clothes or unbutton, clear the place.

- Re assure the patient.

- Monitor and record vital observations until help arrives.

Interventions in the hospital

Put patient on oxygen therapy. Intubate the patient with endotracheal tube, connected to oxygen cylinder.

FOR CHEMICAL BURNS

The commonest cause of chemical burns in Uganda are domestic fights and it’s commonly women to women.

FIRST AID

- Ensure your safety.

- Disperse the powerful chemical by wiping away the chemical, pouring water (plenty) for about 30min. This dilutes the chemical.

- Arrange to transfer patient to hospital but label the chemical if you have identified it.

- Do not attempt to neutralize the chemical with another chemical.

- Ensure that you remove contaminated clothing.

- If the face has been burnt, expect the burns of the airway. Make sure that the airway is open and functioning.

How do you recognize chemical burns

- There may be chemicals in the vicinity.

- The pain is intense and stinging (itching).

- Later discoloration, blistering and peeling of the skin forming wound.

- Supportive treatment with anti-inflammatory drugs, anxiolytics, painkillers.

- Re-assure the patient.

FOR ELECTRIC BURNS

These occur when electricity passes through the body, person a conductor through which electricity passes. Most of the visible damage occurs at points of entry and exit of the current. You may have an internal tract where wounds are mainly concentrated. The current follows mainly muscle, nerves and blood vessels. If it follows the nerves, it can cause cardiac arrest which is the commonest cause of death in electric burns.

NOTE:

The current will cause muscle spasms which may prevent patient from breaking contact with electric source hence continues electric shock. Switch off the main switch. Do not touch a patient with live hands or metallic materials to break the contact. Assess the ABC immediately. Shout for help. Be safe, do something and waste no time.

FIRST AID {AIMS}

- Ensure your safety first.

- Ensure that electric source is disconnected or blocked i.e you may use your shoes or clothes to disconnect the source from patient.

- Flood the exit and entry points with water to cool the burn and prevent further burning process.

- Protect the burn from infection.

- Re-assure

- Give treatment for shock.

ASSESSMENT FOR BURNS TO THE EYE.

Patient is usually unconscious or semi-conscious. If eyes are burnt with chemicals, it will cause scarring and blindness so gets water and wash the eyes to dilute and disperse the acid. Let them not rub the eyes (don’t touch the eyes), continue pouring water in the eyes.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS OF EYE BURNS.

- Continue watering the eyes

- Swollen

- redness

Treatment

- Have gloves on.

- Lie the patient with the affected eye low and most so that water does not affect the rest of the face.

- Open that eye and run cold water for more than 30 minutes.

- Make sure that the water is penetrating into all parts of the eye. Open eye with your hands if they cannot open.

- Get a clean bandage and close the eye until the opthalmist comes.

- Try to identify the chemical and record or label.

GENERAL MANAGEMENT OF BURNS

Aims of management

- To arrest bleeding.

- To prevent the condition from worsening.

- To preserve life.

- To correct electrolyte imbalances. Etc

N.B Burns with a TBSA greater than 15% the following is done. It is a surgical emergency so quit assessment and immediate care is needed plus quick admission. (Immediate nursing care).

Airway maintenance

Through opening and clearing the airway, In case of a suspected cervical spine, keep movements of the neck to a minimum and never hyperflexion or hyperextend to head or neck. If smoke inhalation is suspected intubate before oedema makes it difficult. The head of the bed is elevated and nasal pharynx suction is done incase of excessive secretions.

Breathing and ventilation.

Expose the chest and make sure that chest expansion is adequate. Always provide oxygen in severe burns or when inhalation injury is suspected give 4-8 hr/min. Assess breathing sounds and respiratory rate. Monitor for hypoxia. Encourage aggressive pulmonary care e.g. turning, coughing and deep breathing.

Circulation and hemorrhage control

Stop bleeding with direct pressure. Check capillary if greater than 2secs it means hypovolaemia. Monitor pulse and check pallor which occurs with 30%. Insert 2 large bore peripheral IV lines in superficial burns.

Assessment of the neurological status.

This is done through using a glasgowcoma scale. This helps to check the levels of consciousness that is checking;

- Alertness (A)

- Response to vocal stimuli (V)

- Response to painful stimuli (U)

- Unresponsive.

Examine the pupils for light reaction. Hypoxia can cause reduced levels of response. Keep the patient flat and covered with a sterile sheet to relieve the pain induced by circulatory air currents. Keep the patient warm and check for any adherent clothing, cut around it, when removing the cloth i.e cut around the edges of the clothes disturbing the wound as little as possible.

GENERAL NURSING CARE OF A BURN PATIENT

Maintenance of an aseptic environment.

All attendants must wear capes, gowns, masks and cover shoes. Hands should be washed thoroughly. Cleaning should consist of sloughing skin and use of aseptic solution like hibitane or savlon, the surface is then dried with warm air or sterile dressing (gauze). Afterwards the burnt area is treated by either the exposure method or closed of dressing.

Management of wounds.

- Nurse the patient in a special room to prevent infections (burns are normally sterile). Make sure that you maintain asepsis as much as possible.

- Avoid touching the wound with bear hands i.e. use sterile gloves and use a disinfectant after attending to the patient.

- You must have a mask while examining the patient.

- Use the mosquito net to protect the patient from flies.

- Limit visitors as these increase the risk of infection we give definitive treatment (dress) after resuscitation for burns involving the eyes attend to airway then the burnt eyes and resuscitation later.

FLUID REPLACEMENT

Always replace the lost fluids, can be IV or orally since fluid absorption in the GIT is now very poor. IV fluids are recommended. If an adult loses 15% of the body fluid or as little as 10% in a small child, this will lead to shock. Replacement needs to be continued for at least 48hours.

In deep burns, plasma is given as this is what the patient is losing in 48hours. Towards the end of 48hours, whole blood is given to replace RBCs destroyed, later N/S to replace electrolytes. Glucose to replace energy loss.

Fluid Replacement Calculation (Parkland Formula basis)

The volume of fluid replacement (Y) = (weight in kg X surface area of burns) mls / 2. This volume is given over 8 hours.

Example: Y = (70kg X 20%) / 2 = 700mls. Y=700mls in 4 hours so multiply it by 2 = 1400mls in first 8hours.

- Y=1400mls in the next 16hours

- Y=1400mls in the next 24hours

But adults require 3 liters in 24hours with or without burns (normal physiological fluid requirement). How much is needed Z = (3000x1)/24 = 125mls per hour.

The rate of fluid loss in children below 6yrs is twice that of adults hence double the fluids to be replaced.

Management of Wounds

- Nurse the patient in a special room to prevent infections (burns are normally sterile).

- Avoid touching the wound with bear hands i.e. use sterile gloves and use a disinfectant after attending to the patient.

- You must have a mask while examining the patient.

- Use the mosquito net to protect the patient from flies.

- Limit visitors as these increase the risk of infection.

EXPOSED METHOD

Nothing touches the burn except air and anti-bacterial agent e.g. hibitane, ghee and honey. This indicates for burns of the face especially scalds. It is good for areas that are difficult to dress e.g. perineum, buttocks, face, Axilla.

OCCLUSIVE / CLOSED METHOD.

This method keeps the wound sterile, also aims at applying anti-bacterial agents. E.g. ghee, honey, neomycin cream, tetracycline, hibitane etc.

PROCEDURE FOR BURN DRESSING APPLICATION

This procedure emphasizes a "no-touch" sterile technique to prevent infection.

- Ensure Sterility: Utilize a number touch technique, meaning no human hand shall directly touch the burn or the dressing materials, except when sterile. All instruments used must be sterile.

- Consider Sedation: Administer appropriate sedation if required, to ensure patient comfort and cooperation during the procedure.

- Clean the Area: Gently clean the burn wound and the surrounding healthy skin with Chlorhexidine solution.

- Manage Blisters: Leave any blisters intact; do not puncture them, as they provide a natural protective barrier against infection.

- Apply Impregnated Gauze: Using a sterile spatula, carefully apply the impregnated gauze directly onto the burn wound.

- Apply Dry Gauze: Cover the impregnated gauze with at least 2cm of dry gauze.

- Add Cotton Wool: Place approximately 3cm of cotton wool over the dry gauze layer.

- Secure with Crepe Bandage: Apply a crepe bandage to secure all layers of the dressing.

- Extend Dressing Margins: Ensure the entire dressing extends beyond the wound margin by about 10cm to provide adequate coverage and protection.

Prevention of Burns

- Treat the epileptics, teach them, and mobilize the community about epileptics with burns.

- Raised fire places.

- Keep flues out of the houses e.g. petrol.

- Keep chemical in raised places and out of reach of children.

- Avoid bleaching.

- Keep children out of hot or fire places.

COMPLICATIONS OF BURNS

- Shock.

- Excessive oedema, quite dangerous if burns are of the face, neck as it causes obstruction of the airway and oesophagus.

- Renal failure; due to failure to give adequately fluids.

- Toxaemia and infections; infection of the burnt area causing sepsis resulting in septicaemia, gas gangrene and tetanus.

- Depression of the bone marrow.

- Contractures.

- Keloid formation

- Electrolyte imbalance

- Anaemia due to haemolysis.

- Thrombosis due to plasma loss.

- GIT bleeding, ulcers develop due to increased production of gastric acid.

- Paralytic ileus.

- Sepsis.

- Neuromas

- Cosmetic disfigurement

- Mal-function of the body part

BURNS LECTURE NOTES Read More »

Surgical Shock

COMMON SURGICAL CONDITIONS

SHOCK

Definition

- Shock is a state of poor perfusion with impaired cellular metabolism manifesting with severe pathophysiological abnormalities. It is due to circulatory collapse and tissue hypoxia. Shock is meant by ‘inadequate perfusion` to maintain normal organ function.

- The condition associated with circulatory collapse when the arterial blood pressure is too low to maintain an adequate supply of blood to the tissues.

- The failure of the circulatory system to adequately supply oxygen to the tissues.

Shock is a life-threatening medical condition characterized by inadequate tissue perfusion and oxygenation, leading to cellular dysfunction, widespread organ damage, and if uncorrected, irreversible organ failure and death. It's not simply low blood pressure, but rather a critical imbalance between the demand for oxygen and nutrients by the cells and the body's ability to deliver them.

ETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Shock has a multitude of causes. The most common cause of shock is severe blood loss i.e. if it exceeds 1.2 liters.

The circulation may fail because of the following:

Sudden malfunction of the heart. This may occur as a result of:- Coronary arterial occlusion with acute myocardial ischaemia.

- Trauma with structure damage to the heart

- Toxaemia – bacterial or viral

- Effects of drugs

- Postoperative atelectasis and pneumonia

- Thoracic injuries, particularly tension pneumothorax, bruising and laceration of the lungs

- Obstruction of the pulmonary artery by an embolus.

- Disturbances of lung function following surgery and anesthesia.

- Whole blood – haemorrhage

- Plasma – significant in burns

- Water and electrolyte which occurs in: Peritonitis, Intestinal obstruction and paralytic ileus, Severe diarrhoea and vomiting.

- Adrenal deficiency

- The common faint. The arterioles in the muscle relax

- Over dosage of drugs eg analgesic like pethedine

- Following therapy with beta blocking agents for angina, hypertension etc

- Noxious stimuli, such as pain, if severe with cause vasodilation

- Systolic dysfunction: it is the inability of the heart to pump forward like in myocardial infarction and cardial myopathy

- Diastolic dysfunction: it is the inability of the heart to fill e.g. cardiac tamponade, ventricular hypertrophy and cardial myopathy

- Dysrhythmias eg in bradyrhythmias and tarchyrhythmias

- Structural factors like valvular stenosis or regurgitation, ventricular septal rapture

- Internal bleeding like fracture of long bones, ruptured spleen heamopneumothorax and severe pancreatitis

- Fluid shift like in burns and cysts

- Spinal anesthesia

- Vasomotor center depression

Types, and Clinical Manifestations

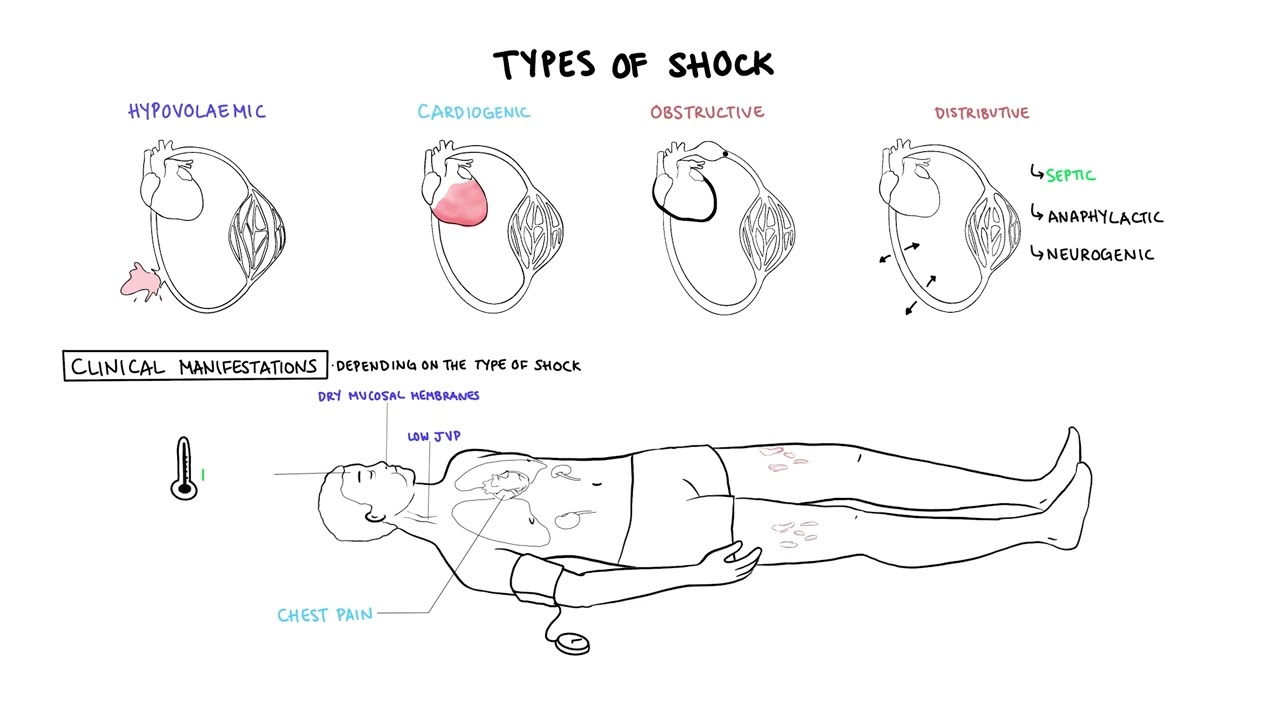

Types of Shock: Categorization by Underlying Pathophysiology

Shock is broadly classified into several types based on the primary physiological mechanism causing the inadequate tissue perfusion. While these types have distinct primary causes, they often share common clinical features and can coexist or lead to one another.

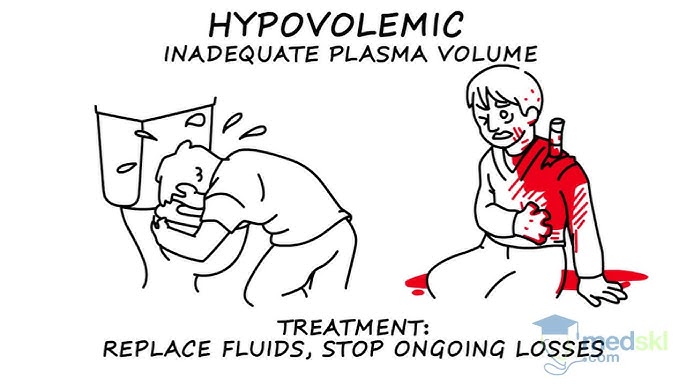

1. Hypovolemic Shock (Inadequate Circulating Volume)

- Trauma (external or internal bleeding)

- Gastrointestinal bleeding (e.g., peptic ulcer, variceal bleeding)

- Post-surgical bleeding

- Obstetric hemorrhage (e.g., postpartum hemorrhage)

- Aortic rupture

- Severe Dehydration: Vomiting, diarrhea, inadequate fluid intake.

- Severe Burns: Massive fluid shifts from intravascular space into interstitial space.

- Peritonitis/Bowel Obstruction: Fluid sequestration within the abdominal cavity or bowel lumen.

- Diabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA) / Hyperosmolar Hyperglycemic State (HHS): Profound osmotic diuresis.

- Excessive Diuretic Use.

2. Cardiogenic Shock (Pump Failure)

- Myocardial Infarction (MI): Especially extensive anterior or left ventricular MI, which damages a significant portion of the heart muscle.

- Severe Arrhythmias: Tachyarrhythmias (e.g., ventricular tachycardia, atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response) or bradyarrhythmias that significantly reduce ventricular filling time or heart rate.

- Valvular Heart Disease: Acute severe mitral regurgitation, aortic stenosis.

- Cardiomyopathies: Acute exacerbation of chronic heart failure.

- Myocarditis: Inflammation of the heart muscle.

- Acute Papillary Muscle Rupture.

3. Distributive Shock (Vasogenic Shock / Abnormal Vasodilation)

a. Septic Shock:

- Definition: A life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection, leading to persistent hypotension requiring vasopressors to maintain mean arterial pressure (MAP) ≥ 65 mmHg and having a serum lactate level > 2 mmol/L despite adequate fluid resuscitation.

- Pathophysiology: Triggered by severe infection (bacterial, viral, fungal). Pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) released from pathogens and damaged host cells activate a complex inflammatory cascade. This leads to widespread endothelial dysfunction, microcirculatory alterations, profound vasodilation, increased capillary permeability (fluid leakage into interstitial spaces leading to relative hypovolemia and edema), and myocardial depression.

- Causes: Severe infections, particularly with Gram-negative bacteria (e.g., *E. coli, Klebsiella, Pseudomonas*) or Gram-positive bacteria (e.g., *Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae*). Common sources include pneumonia, urinary tract infections, abdominal infections (e.g., appendicitis, diverticulitis), and skin/soft tissue infections.

- Clinical Features: Often presents as "warm shock" in early stages (warm, flushed skin, bounding pulses) due to vasodilation, progressing to "cold shock" as compensatory mechanisms fail and cardiac output falls.

- Definition: A severe, life-threatening systemic allergic reaction characterized by rapid onset of profound vasodilation, increased vascular permeability, and bronchoconstriction.

- Pathophysiology: Exposure to an allergen triggers a massive release of inflammatory mediators (e.g., histamine, leukotrienes, prostaglandins) from mast cells and basophils. These mediators cause widespread vasodilation and leakage of fluid from capillaries into the interstitial space, leading to circulatory collapse and airway obstruction.

- Causes: Exposure to allergens such as insect stings, certain foods (e.g., peanuts, shellfish), medications (e.g., antibiotics, NSAIDs), or latex.

- Definition: Occurs due to loss of sympathetic nervous system tone, leading to widespread vasodilation and pooling of blood in the periphery. Unlike other forms of shock, the heart rate may be paradoxically normal or even bradycardic.

- Pathophysiology: Damage to the sympathetic nervous system (typically above T6) interrupts the normal vasoconstrictive impulses to peripheral blood vessels. This results in unopposed parasympathetic activity, leading to profound vasodilation and often bradycardia.

- Causes:

- Spinal cord injury (most common cause).

- Spinal anesthesia.

- Guillain-Barré Syndrome.

- Severe head trauma (less common as a primary cause).

- Certain drugs (e.g., ganglionic blockers, adrenergic antagonists).

- Definition: Shock resulting from acute hormonal deficiencies that disrupt normal cardiovascular function and metabolic processes.

- Causes: Adrenal crisis (acute adrenal insufficiency leading to severe hypotension refractory to fluids and vasopressors due to lack of cortisol) or myxedema coma (severe hypothyroidism leading to decreased cardiac output, bradycardia, and hypothermia).

4. Obstructive Shock (Extracardiac Obstruction to Blood Flow)

- Pulmonary Embolism (PE): Massive PE obstructs blood flow from the right ventricle into the pulmonary circulation.

- Cardiac Tamponade: Accumulation of fluid or blood in the pericardial sac, compressing the heart and preventing adequate ventricular filling.

- Tension Pneumothorax: Air accumulation in the pleural space collapses the lung and shifts the mediastinum, compressing the great vessels and heart.

- Constrictive Pericarditis (severe acute exacerbation).

- Critical Valvular Stenosis (less common as primary obstructive shock).

5. Vasovagal Shock (Neurocardiogenic Syncope)

- Definition: While often presenting as syncope (fainting), severe forms can lead to a transient state of shock. It's characterized by a sudden, exaggerated reflex response that results in both widespread peripheral vasodilation and bradycardia.

- Pathophysiology: Triggered by certain stimuli (e.g., pain, fear, emotional stress, prolonged standing, specific odors). The vagus nerve is overstimulated, leading to parasympathetic activation (bradycardia) and sympathetic inhibition (vasodilation), causing a temporary drop in blood pressure and cerebral perfusion.

- Clinical Significance: Usually self-limiting and resolves upon lying down. Rarely life-threatening unless associated with significant trauma from a fall. Not considered a true "shock state" in the critical care sense as it's typically transient and reversible with simple measures.

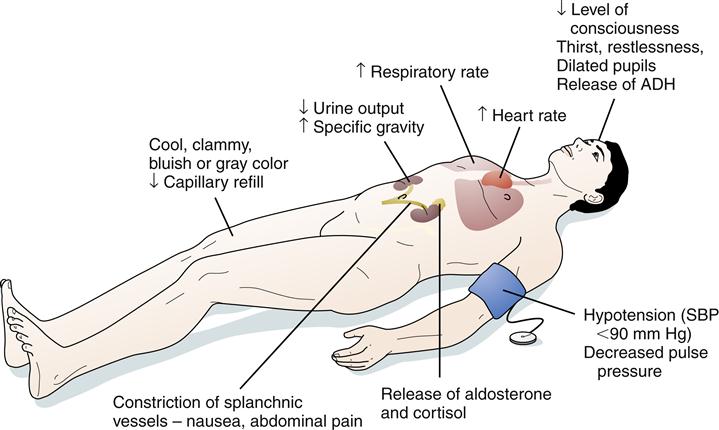

Recognition Features of Shock / Signs and Symptoms of Shock

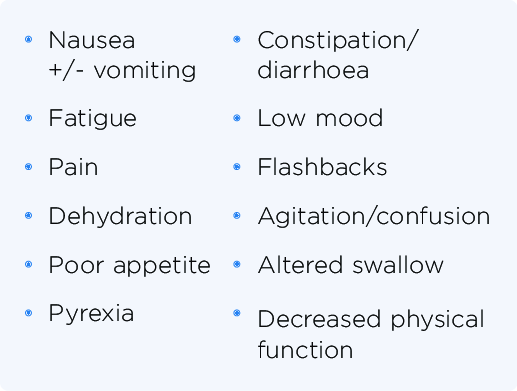

The signs and symptoms of shock are a reflection of the body's compensatory mechanisms attempting to maintain vital organ perfusion, followed by the failure of these mechanisms as shock progresses. The specific presentation can vary slightly depending on the type and stage of shock.

I. Early / Compensatory Stage (Body's attempt to maintain vital organ perfusion)

In this initial stage, the body activates its sympathetic nervous system and hormonal responses to maintain blood pressure and vital organ blood flow. This often leads to increased heart rate and vasoconstriction.

Cardiovascular:- Rapid Pulse (Tachycardia): The earliest and most consistent sign. The heart beats faster to compensate for reduced cardiac output.

- Normal to Slightly Decreased Blood Pressure: The body is still able to maintain BP through vasoconstriction.

- Pale, Cool, Clammy Skin: Due to peripheral vasoconstriction shunting blood away from the skin to vital organs. The clamminess is due to diaphoresis (sweating) caused by sympathetic stimulation.

- Delayed Capillary Refill: >2 seconds (indicates poor peripheral perfusion).

- Restlessness, Anxiety, Agitation: Early signs of cerebral hypoperfusion and catecholamine release.

- Increased Thirst: Due to fluid shifts and activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system.

- Oliguria: Decreased urine output (< 0.5 mL/kg/hr) as kidneys conserve fluid and blood flow is shunted away.

- Slightly Increased Respiratory Rate: Due to metabolic acidosis (from anaerobic metabolism) and increased oxygen demand.

II. Progressive / Decompensatory Stage (Compensatory mechanisms begin to fail)

As shock progresses, the compensatory mechanisms become overwhelmed, leading to widespread cellular hypoxia, anaerobic metabolism, and accumulation of lactic acid. Organ function begins to deteriorate.

Cardiovascular:- Hypotension: Significant drop in systolic blood pressure (<90 mmHg or MAP <65 mmHg) or a drop of >40 mmHg from baseline. This is a critical sign that compensation has failed.

- Weak, Thready Pulse: Rapid but difficult to palpate, indicating profound vasoconstriction and low stroke volume.

- Progressively Colder, Mottled Skin: Especially in extremities (e.g., "grey-blue skin," cyanosis of lips and nail beds) due to severe peripheral vasoconstriction and pooling of deoxygenated blood.

- Lethargy, Drowsiness, Confusion: Worsening cerebral hypoperfusion.

- Decreased Responsiveness to Stimuli.

- Nausea, Vomiting: Due to reduced blood flow to the GI tract.

- Abdominal Pain.

- Rapid, Shallow Breathing (Tachypnea): The body's attempt to compensate for metabolic acidosis.

- Increasing Lactic Acidosis: Due to anaerobic metabolism.

III. Irreversible / Refractory Stage (Widespread cellular and organ damage)

In this final stage, cellular and organ damage becomes so severe that it is irreversible, even with aggressive interventions. Multi-organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) develops, leading inevitably to death.

Cardiovascular:- Profound Hypotension: Unresponsive to fluids and vasopressors.

- Severe Tachycardia or Bradycardia: With eventual cardiac arrest.

- Absent Peripheral Pulses.

- Unconsciousness, Coma.

- Fixed, Dilated Pupils.

- Loss of Reflexes.

- Gasping for Air (Agonal Respirations): Severe respiratory distress.

- Respiratory Failure.

- Anuria: Complete cessation of urine production.

- Acute Kidney Injury.

- Severe Lactic Acidosis: Uncorrectable.

- Electrolyte Imbalances.

- Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation (DIC): Widespread clotting and bleeding.

- Multi-Organ System Failure (MOSF).

Special Considerations: Warm Shock (Septic Shock in Early Stages)

While most forms of shock present with cool, clammy skin due to vasoconstriction, early septic shock (hyperdynamic or "warm shock" phase) can present differently due to the profound systemic vasodilation:

- Warm, Dry, Flushed Skin: Due to peripheral vasodilation.

- Rapid, Strong (Bounding) Pulse: Indicating a hyperdynamic state and decreased systemic vascular resistance.

- Fever: Evidence of underlying infection.

- Hyperventilation: To compensate for metabolic acidosis.

- Despite these initial "warm" signs, tissue perfusion is still inadequate at the microcirculatory level, and this phase rapidly progresses to decompensated ("cold") shock if not aggressively treated.

MANAGEMENT OF SHOCK

AIMS

- To treat the cause

- To improve cardiac function

- To improve tissue perfusion

Emergency treatment for shock

- Help patient to lie down and place patient in supine position

- Cover patient and keep him or her warm

- Raise and support her legs as high as possible

- Administer oxygen if possible

- Determine underlying cause and treat if possible e.g. applying pressure for bleeding.

- Lessen any tight clothing, undo anything that constrict the neck, chest and wrist

- Monitor breathing, pulse and response

- Monitor and record vital observation like pulse breathing, monitor level of response, if the casualty become unconscious, open the airway and check breathing.

General management

- Treat the cause e.g. arrest haemorrhage, drain pus etc.

- Fluid replacement e.g. plasma normal saline dextrose ringers lactate, plasma expanders maximum 1 liter can be given in 24hours.

- Blood transfusion is done whenever necessary, hypotonic solutions like dextrose are poor volume expanders and so should not be used in shock.

- Inotropic agents e.g. dopamine, dobutamine, adrenaline infusions.

- Correction of acid base balance. Acidosis is corrected by using 8.4 sodium bicarbonate intravenously.

- Steroid is often life saving. 500- 1000mg of hydrocortisone can be given. It improves perfusion, reduces the capillary leakage and systemic inflammatory effects.

- Antibiotics in patients with patients with sepsis; proper control of blood sugar and ketosis in diabetic patients.

- Catheterization to measure urine output (30 – 50mls/hour or > 0.5 ml/kg/ hour should be maintained).

- Nasal oxygen to improve oxygenation or ventilator support with intensive care unit monitoring has to be done.

- Haemodialysis (a process of removing a waste part e.g. kidney) may be necessary if kidneys are not functioning.

- Control pain using morphine (4mg iv).

- Injection ranitidine iv or omeprazole iv or pantoprazole iv.

- Activated c protein, it is beneficial as it prevents the release of inflammatory response.

- Diuretics, mannitol is an osmotic that neither absorbed in the renal tubules nor metabolized. It may be given when acidosis and Oliguria have been corrected but if oliguria persist frusemide may also be given.

- Anticoagulants may occasionally be indicated if micro- circulatory thrombosis is suspected.

Prevention of shock

Pre operative measures

- Take thorough history which include biographic data, medical history, obstetric history, gynaecological.

- Assess the level of consciousness.

- Take the baseline vital observation which include temperature, pulse, respiration and blood.

- General body assessment from head to toe to rule out abnormalities like oedema, hemorrhage, cyanosis and pallor.

- If there is external heamorrhage arrest the bleeding by positioning the patient.

- Empty the bladder by passing a catheter.

- Antibiotic prophylaxis is given to prevent sepsis.

- Take investigation such as hemoglobin estimation, cross matching, blood grouping and cross matching, clotting factor, malaria slide etc.

- Give anxiolytics to allay anxiety and give pain killer to reduce pain.

- Resuscitate patient with iv fluids.

- Reassure the patient.

- The patient should be educated about physical exercises which are done post operatively.

- Circulatory collapse should be avoided by strenuous measures if all possible.

- Preoperatively patient should be fit as possible from the point of view of the circulatory system: His blood should be a adequate in quality and volume, His tissues should be hydrated adequately, He should be mobile so that there is no stagnation in the circulatory system.

Intra operatively

- Patient is kept warm on his journey from the ward to the theater and back.

- Fear is allied and tranquiller are commonly used pre- operatively.

- The blood pressure is monitored continuously and recorded more so for the serious cases.

- Blood and fluid replacement is commenced in good time and the patient is monitored using fluid balance chart.

- Major operations are commenced only after satisfactory infusions have been established.

- The head of the bed is lowered if the blood pressure falls (Trendelenburg position).

- The anesthetist induces and maintains an adequate level of anesthesia ensuring good oxygenation and tissue perfusion.

Post operatively measures

- Fluid and electrolyte replacement (saline, 5% dextrose, Hartman solution, plasma and blood as indicated).

- Position the patient in a recovery position.

- Maintain air way patent.

- Give antibiotics to prevent infections.

- Give inflammatory drugs.

- Check the conscious level of the patient.

- Initiate exercise like coughing, deep breathing and ambulation to aid normal circulation.

- Rest and relieve of pain are continued to prevent shock.

General Nursing Considerations and Principles for Patients in Shock

Nursing care for a patient in shock is complex, dynamic, and requires rapid assessment, intervention, and continuous monitoring. The primary goals are to optimize tissue perfusion, restore hemodynamic stability, identify and treat the underlying cause, and prevent complications. Nurses work collaboratively with the medical team to implement a comprehensive plan of care.

Nursing Diagnoses)

Nursing diagnoses guide the individualized care plan for patients. Examples for a patient in shock might include:

- Decreased Cardiac Output related to altered preload, afterload, contractility, or heart rate, as evidenced by hypotension, tachycardia, altered mental status, decreased urine output, and cool, clammy skin.

- Ineffective Tissue Perfusion (Cardiac, Cerebral, Renal, Gastrointestinal, Peripheral) related to hypovolemia, impaired cardiac pump function, maldistribution of blood flow, or obstruction, as evidenced by pallor, cyanosis, delayed capillary refill, weak peripheral pulses, altered mental status, oliguria, and increased serum lactate.

- Impaired Gas Exchange related to ventilation/perfusion mismatch, increased metabolic demand, or pulmonary edema, as evidenced by tachypnea, dyspnea, abnormal blood gas values, and cyanosis.

- Deficient Fluid Volume related to active fluid loss, failure of regulatory mechanisms, or third-space fluid shift, as evidenced by hypotension, tachycardia, decreased urine output, and dry mucous membranes.

- Risk for Infection related to invasive procedures, compromised immune status, or presence of underlying infection.

- Acute Confusion related to decreased cerebral perfusion, metabolic imbalances, or hypoxia, as evidenced by disorientation, agitation, or altered level of consciousness.

- Risk for Imbalanced Body Temperature related to altered metabolic rate, infection, or environmental factors.

- Anxiety/Fear related to critical illness, threat of death, or unpredictable prognosis.

Nursing Interventions (General Principles - specific actions depend on the type of shock)

Interventions are aimed at supporting vital organ function, addressing the underlying cause, and minimizing further deterioration. These often fall into categories of hemodynamic support, respiratory support, infection control, and monitoring.

1. Optimize Hemodynamic Status and Perfusion: