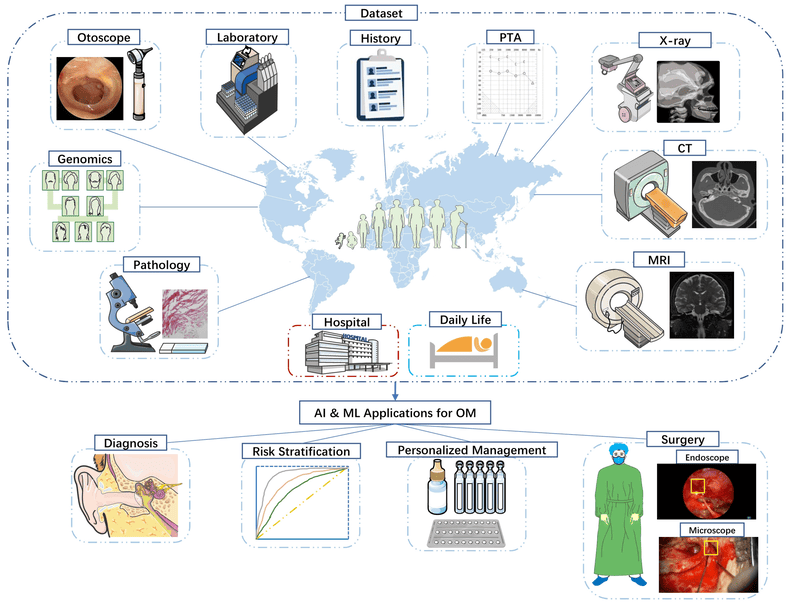

Otitis Media Lecture Notes

Otitis Media (OM) is a broad term encompassing a group of inflammatory diseases of the middle ear.

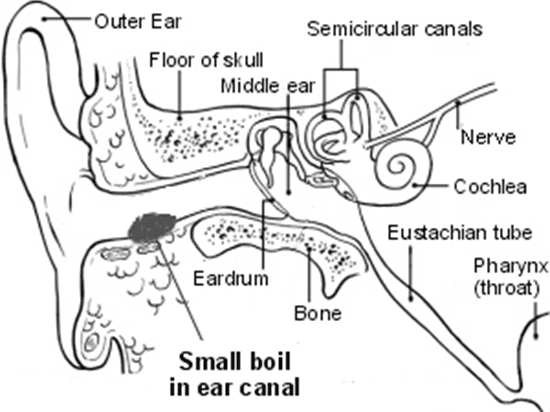

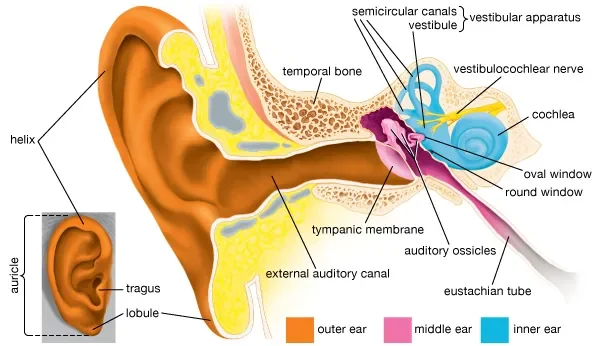

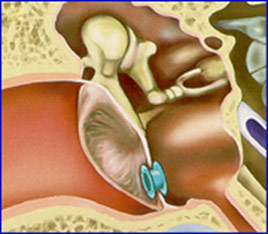

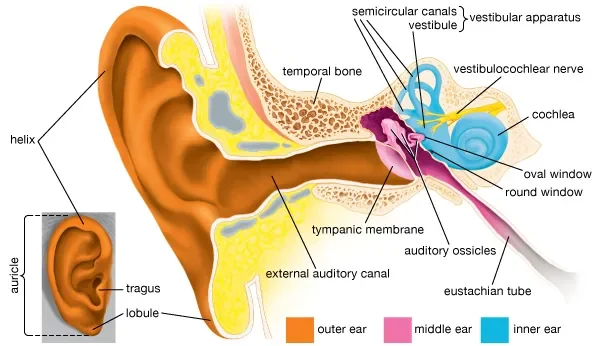

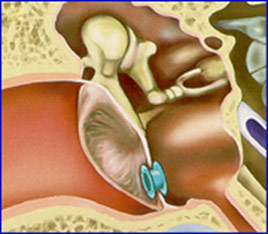

The middle ear is an air-filled cavity located behind the eardrum (tympanic membrane) and contains the ossicles (malleus, incus, stapes), which transmit sound vibrations. It is connected to the nasopharynx by the Eustachian tube.

The different classifications of otitis media are crucial for understanding its pathology, clinical presentation, and management.

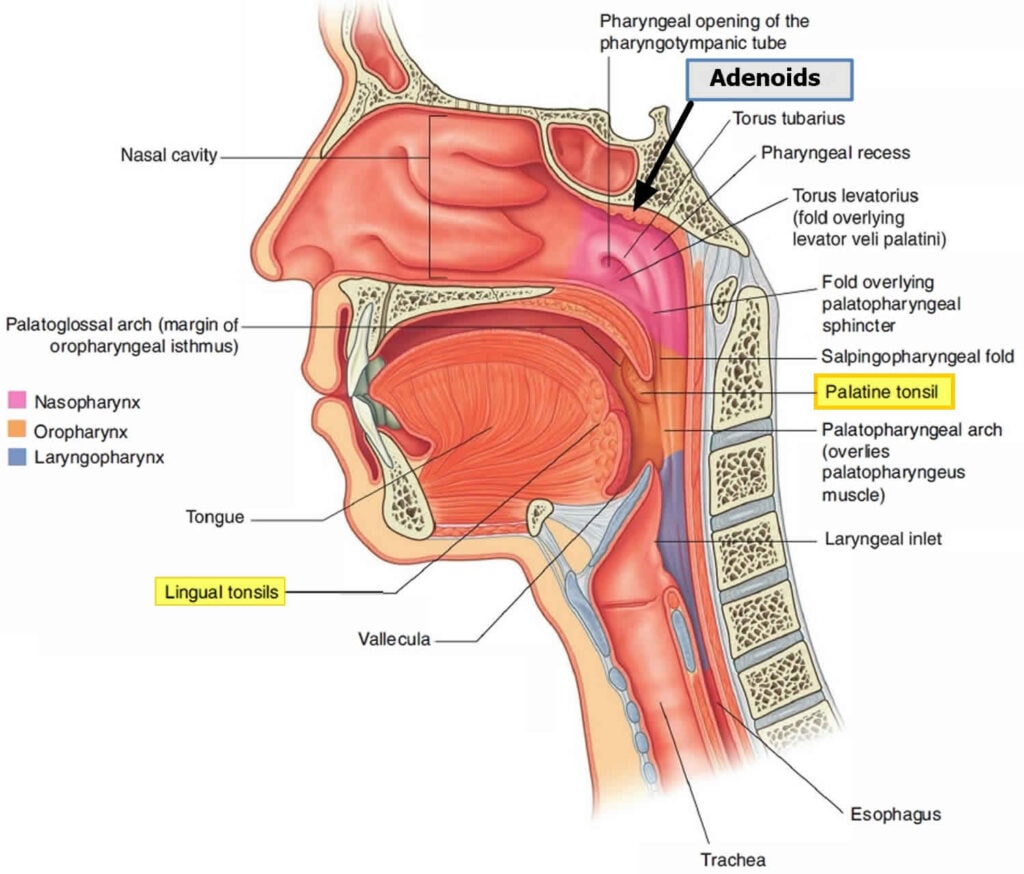

I. Key Anatomical Considerations:

- Middle Ear Space: The air-filled cavity behind the tympanic membrane.

- Tympanic Membrane (Eardrum): Separates the external ear from the middle ear.

- Eustachian Tube: Connects the middle ear to the nasopharynx, responsible for ventilation, drainage, and pressure equalization of the middle ear. Dysfunction of this tube is central to the development of OM.

II. Classifications of Otitis Media

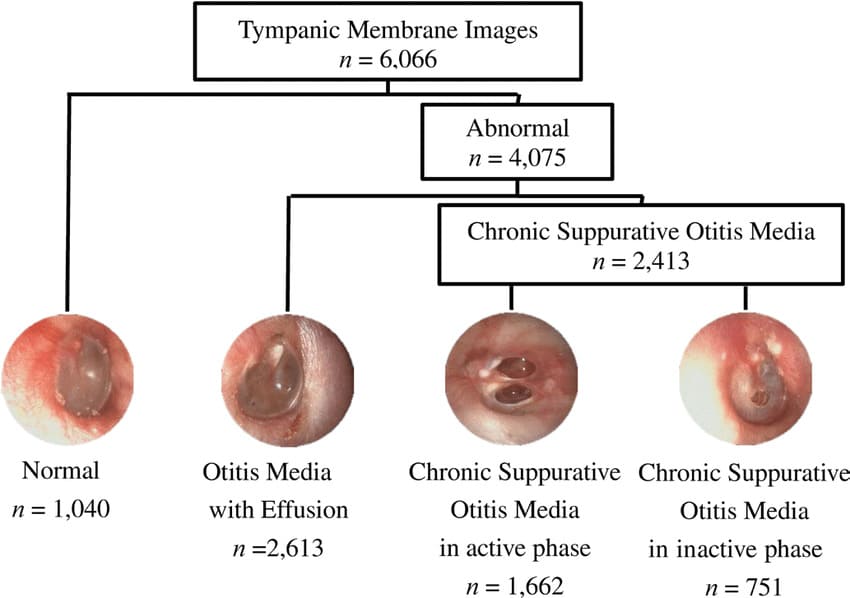

Otitis media is primarily classified based on the presence of effusion (fluid in the middle ear) and the duration and severity of symptoms.

Acute Otitis Media (AOM): An acute inflammatory process of the middle ear, characterized by the rapid onset of signs and symptoms of middle ear inflammation and the presence of middle ear effusion (fluid).

- Key Features:

- Rapid Onset: Symptoms develop quickly, usually within hours to a few days.

- Middle Ear Effusion (MEE): Fluid behind the eardrum.

- Signs of Inflammation: Bulging of the tympanic membrane, limited or absent mobility of the tympanic membrane, redness of the tympanic membrane, and otalgia (ear pain).

- Systemic Symptoms: Fever, irritability, difficulty sleeping, decreased appetite, vomiting, or diarrhea are common, especially in infants and young children.

- Duration: Typically resolves within a few days to weeks.

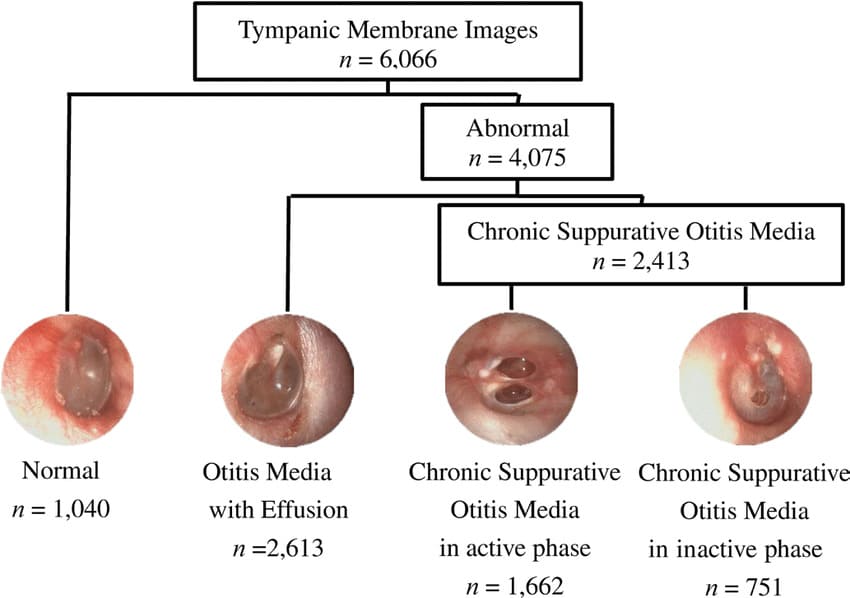

Otitis Media with Effusion (OME), also known as Serous Otitis Media: The presence of non-purulent (non-infected) fluid in the middle ear space without signs or symptoms of acute inflammation.

- Key Features:

- Middle Ear Effusion (MEE): Fluid is present behind the eardrum.

- Absence of Acute Inflammation: No fever, no significant ear pain, no bulging of the eardrum. The tympanic membrane may appear dull, retracted, or show fluid levels/bubbles.

- Silent Presentation: Often asymptomatic, but can cause hearing loss (conductive hearing loss) due to the fluid impairing sound transmission.

- Duration: Can persist for weeks or months after an episode of AOM, or can arise spontaneously due to Eustachian tube dysfunction.

- Significance: While not an active infection, persistent OME can lead to developmental delays, particularly speech and language, in young children due to chronic hearing impairment.

Recurrent Acute Otitis Media (RAOM): Multiple episodes of AOM within a specific timeframe.

- Criteria: defined as:

- 3 or more distinct episodes of AOM in 6 months, OR

- 4 or more distinct episodes of AOM in 12 months, with at least one episode in the preceding 6 months.

- Significance: Indicates a predisposition to middle ear infections, often due to underlying Eustachian tube dysfunction, allergies, or immune factors, and may warrant further investigation or prophylactic measures.

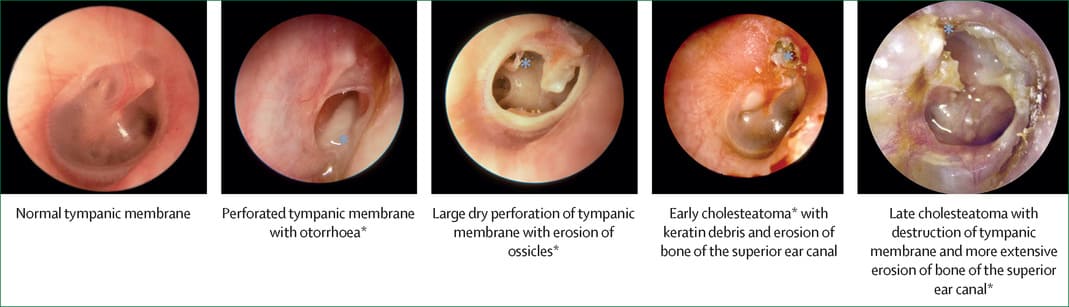

Chronic Suppurative Otitis Media (CSOM): Chronic inflammation of the middle ear and mastoid cavity, characterized by perforation of the tympanic membrane and persistent or recurrent otorrhea (ear discharge) through the perforation for at least 6 weeks.

- Key Features:

- Tympanic Membrane Perforation: A hole in the eardrum.

- Chronic Otorrhea: Persistent drainage from the ear.

- Absence of Acute Symptoms: Usually painless, without fever, unless there's an acute exacerbation.

- Hearing Loss: Conductive hearing loss is common.

- Significance: Represents a long-standing infection that can lead to significant hearing impairment and serious complications if untreated.

Etiology and Pathophysiology of Otitis Media

The development of Otitis Media (OM), particularly Acute Otitis Media (AOM) and Otitis Media with Effusion (OME), is primarily a result of a complex interplay between Eustachian tube dysfunction, microbial colonization, and host factors.

I. Etiology (Causes):

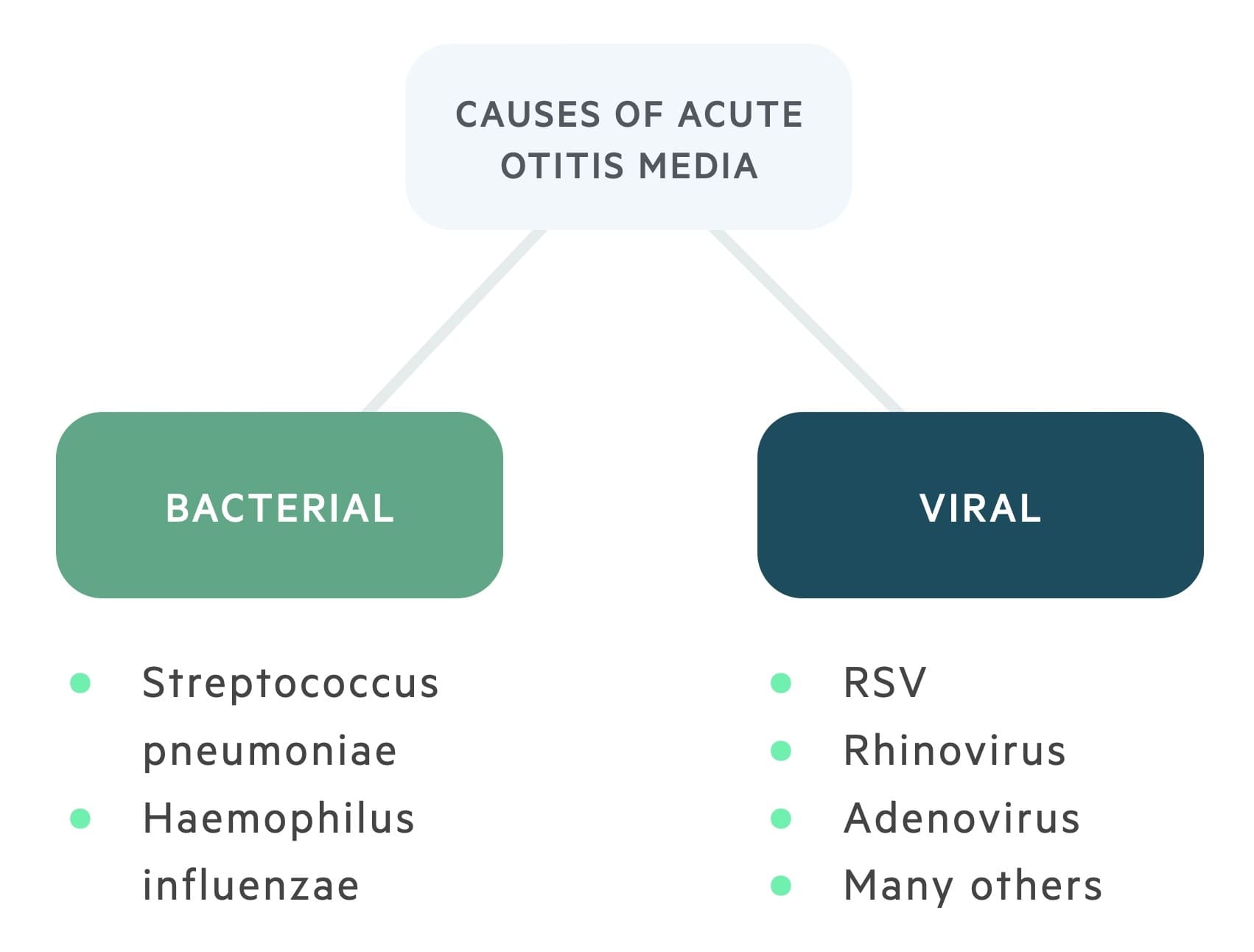

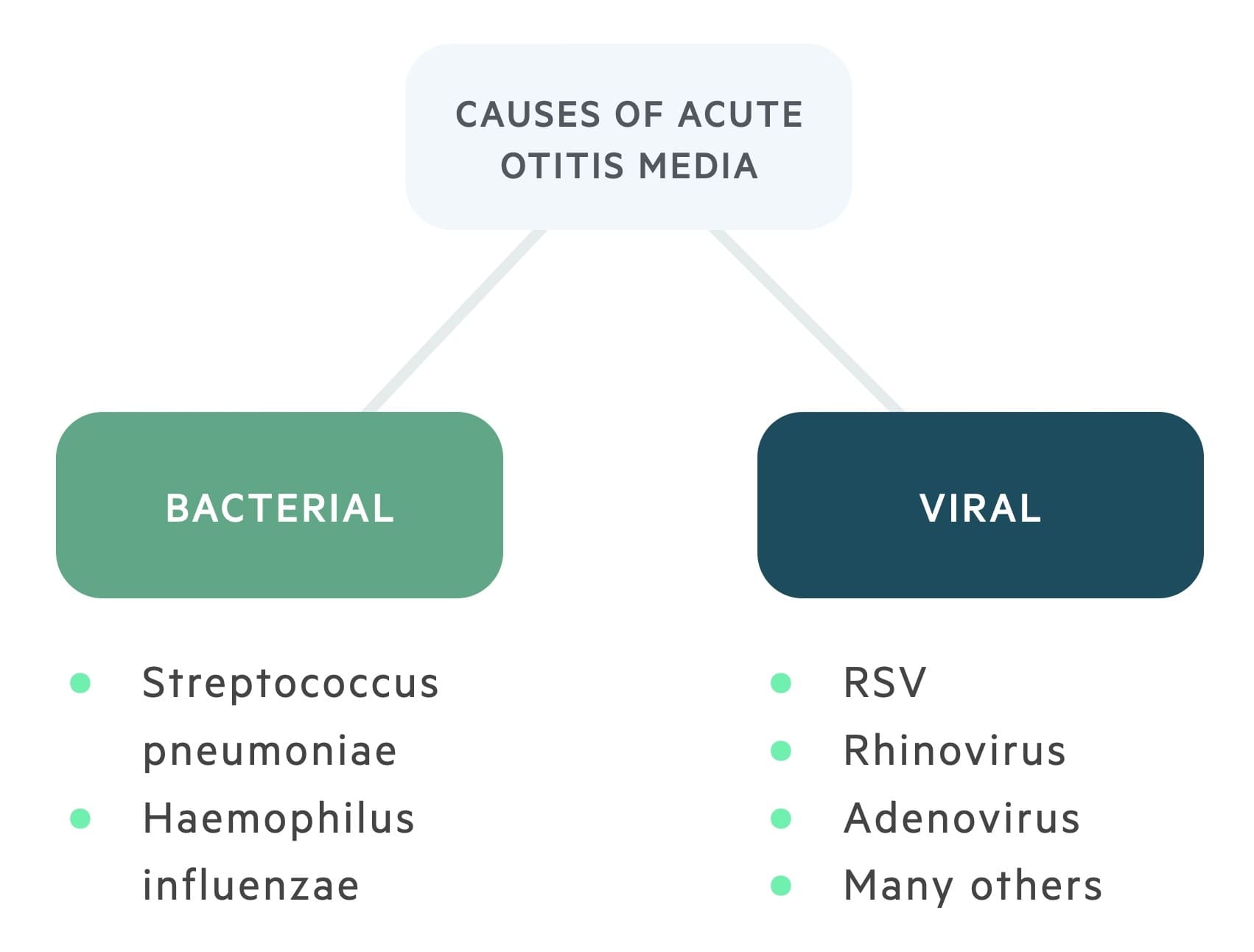

Otitis Media is most commonly triggered by a combination of viral and bacterial infections.

- Viral Infections (Primary Initiators):

- Common Viruses: Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV), Rhinovirus (common cold), Influenza virus, Adenovirus.

- Role: Viral upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs) are often the initial event. They cause inflammation of the nasal passages and nasopharynx, which then extends to the Eustachian tube. This inflammation leads to swelling and increased mucus production, contributing to Eustachian tube dysfunction. Viral infections can also directly impair local immune defenses, making the middle ear more susceptible to bacterial invasion.

- Bacterial Infections (Secondary Invaders):

- Common Bacteria:

- Streptococcus pneumoniae (Pneumococcus): The most common bacterial cause of AOM, accounting for about 25-50% of cases.

- Haemophilus influenzae (non-typeable): The second most common, responsible for 20-40% of cases.

- Moraxella catarrhalis: Accounts for 10-15% of cases.

- Streptococcus pyogenes (Group A Strep): Less common, but can cause more severe disease.

- Role: Following a viral URTI and subsequent Eustachian tube dysfunction, bacteria from the nasopharynx can ascend into the middle ear, where they proliferate in the compromised environment, leading to a full-blown bacterial infection.

- Other Contributing Factors:

- Allergies: Allergic inflammation of the nasal mucosa can also lead to Eustachian tube dysfunction.

- Anatomical Abnormalities: Cleft palate, Down syndrome, or other craniofacial anomalies can predispose individuals to OM due to compromised Eustachian tube function.

- Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD): Refluxed stomach contents can potentially irritate the Eustachian tube opening.

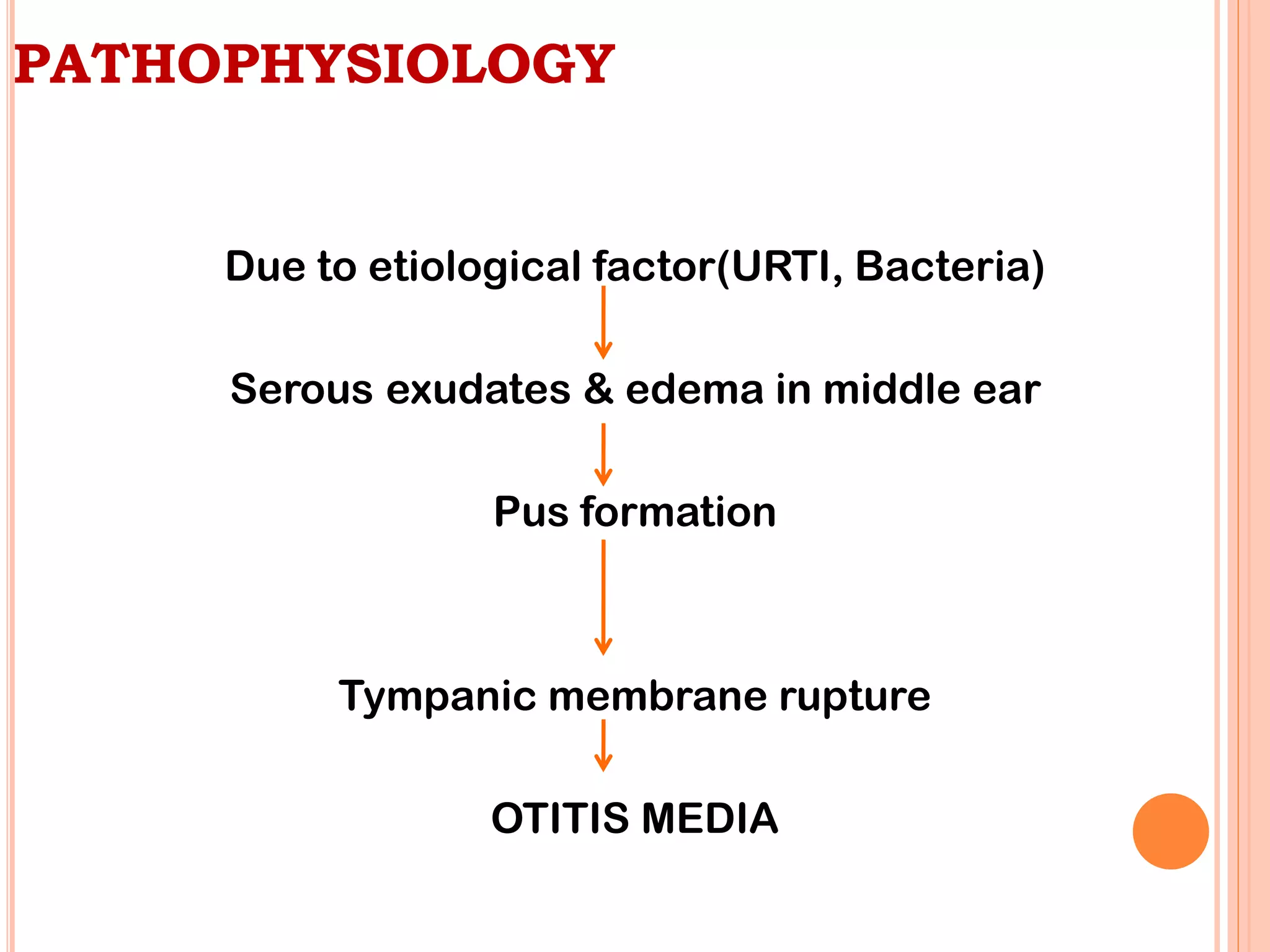

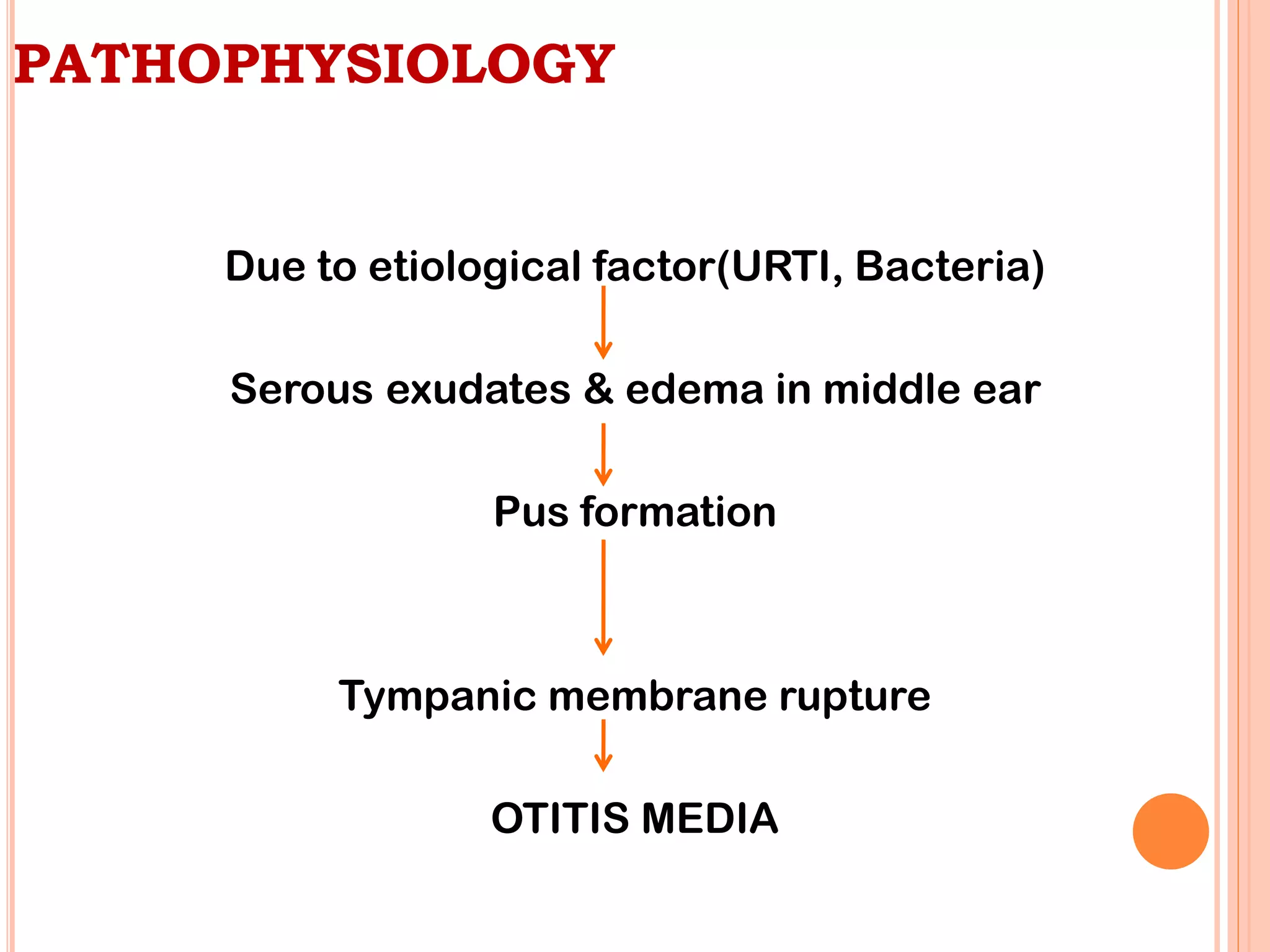

II. Pathophysiology (How the Disease Develops):

The key event in the pathogenesis of most forms of Otitis Media is Eustachian tube dysfunction.

Eustachian Tube Dysfunction (ETD):

- Normal Function: The Eustachian tube normally opens periodically (during swallowing, yawning) to equalize pressure, ventilate the middle ear, and drain secretions into the nasopharynx.

- Impairment:

- Inflammation/Edema: Viral URTIs, allergies, or irritants cause inflammation and swelling of the Eustachian tube mucosa, leading to its blockage.

- Mechanical Obstruction: Enlarged adenoids (especially in children) can physically block the nasopharyngeal opening of the Eustachian tube.

- Consequence: When the Eustachian tube is blocked, the air in the middle ear is gradually absorbed by the surrounding tissues. This creates negative pressure (vacuum) within the middle ear cavity.

Middle Ear Effusion (OME Development):

- Mechanism: The negative pressure in the middle ear causes fluid to be drawn from the mucosal lining (transudation) and promotes the secretion of fluid by the middle ear mucosa.

- Result: This fluid accumulation is Otitis Media with Effusion (OME). At this stage, the fluid is typically sterile or non-purulent. Patients may experience a feeling of fullness in the ear and conductive hearing loss.

Bacterial Colonization and Acute Otitis Media (AOM Development):

- Mechanism: The fluid-filled, negatively pressured middle ear provides an ideal breeding ground for bacteria. Bacteria and viruses from the nasopharynx, which are often present due to the preceding URTI, can easily ascend into the middle ear through the dysfunctional Eustachian tube.

- Result: The bacteria proliferate, leading to an acute inflammatory response:

- Increased Fluid Production: The infection leads to the production of purulent (pus-filled) fluid.

- Tympanic Membrane Changes: The tympanic membrane becomes inflamed, red, and bulges outward due to the pressure of the accumulating pus. Its mobility is reduced or absent.

- Pain (Otalgia): The pressure and inflammation within the middle ear cause significant ear pain.

- Systemic Symptoms: The infection triggers a systemic response, leading to fever, irritability, and general malaise.

Factors Predisposing Children to OM:

- Anatomy of Eustachian Tube: In children, the Eustachian tube is shorter, more horizontal, and wider than in adults, making it easier for pathogens to ascend from the nasopharynx and for secretions to accumulate.

- Immature Immune System: Children's immune systems are still developing, making them more susceptible to infections.

- Adenoidal Hypertrophy: Enlarged adenoids are common in children and can directly obstruct the Eustachian tube.

- Daycare Attendance: Increased exposure to respiratory viruses.

- Exposure to Tobacco Smoke: Impairs ciliary function and increases inflammation.

- Lack of Breastfeeding: Breastfeeding provides antibodies that protect against infections.

Clinical Presentation of otitis media

The clinical presentation of otitis media, particularly Acute Otitis Media (AOM), can vary significantly depending on the patient's age. Infants and young children, who are most commonly affected, often present with non-specific symptoms, making diagnosis challenging.

I. Common Symptoms of Acute Otitis Media (AOM):

- Otalgia (Ear Pain):

- Description: This is the hallmark symptom, often sudden in onset and ranging from mild to severe.

- In older children/adults: They can verbalize "my ear hurts."

- In infants/young children: May manifest as:

- Ear pulling, tugging, or rubbing: While often associated with ear pain, this can also be a non-specific sign and is not always indicative of AOM.

- Increased irritability/fussiness: Especially when lying down, which can increase middle ear pressure.

- Difficulty sleeping: Pain often worsens when supine.

- Unexplained crying.

- Fever: Common, especially in bacterial AOM. Can range from low-grade to high (e.g., >39°C or 102.2°F). NOTE that Absence of fever does not rule out AOM, particularly in viral cases or milder bacterial infections.

- Irritability and Restlessness: Non-specific but common, reflecting general discomfort and pain.

- Difficulty Sleeping: Pain often intensifies when lying flat due to increased middle ear pressure.

- Decreased Appetite / Feeding Difficulties: Swallowing can increase middle ear pressure, exacerbating pain. Sucking (e.g., from a bottle or breast) can also cause pain.

- Vomiting and Diarrhea: More common in younger children, often accompanying systemic infections.

- Muffled Hearing / Hearing Loss: Due to fluid in the middle ear, sound conduction is impaired. Older children may complain of this, while in younger children, it may be noticed as decreased responsiveness to sound.

- Otorrhea (Ear Discharge): If the tympanic membrane perforates, pus may drain from the ear canal. This often leads to immediate pain relief, as the pressure in the middle ear is released. The discharge can be purulent or bloody.

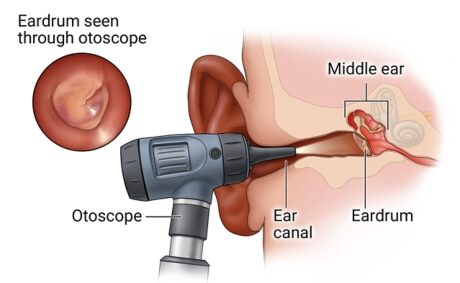

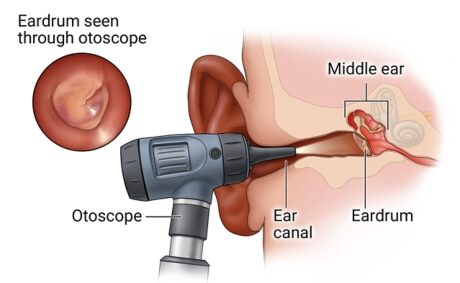

II. Clinical Signs on Physical Examination (Otoscopy):

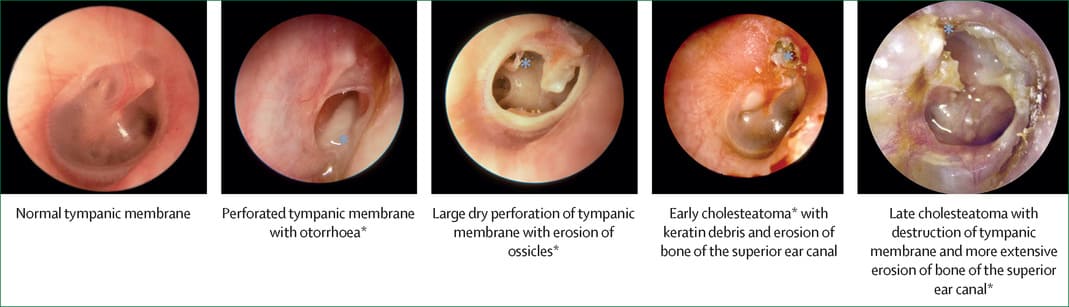

The definitive diagnosis of AOM relies on visual inspection of the tympanic membrane (eardrum) using an otoscope.

- Bulging of the Tympanic Membrane (TM): The most reliable sign of AOM. The eardrum bows outward due to the pressure of fluid/pus behind it.

- Erythema (Redness) of the TM: Indicates inflammation. The TM may appear diffusely red.

- Limited or Absent Mobility of the TM: Assessed with pneumatic otoscopy (puff of air). A healthy TM moves in response to pressure changes; an inflamed or fluid-filled TM will show reduced or no movement.

- Clouding / Opacity of the TM: The eardrum loses its normal translucent appearance and appears opaque.

- Loss of Landmarks: The normal anatomical landmarks (e.g., malleus, cone of light) become obscured due to bulging and inflammation.

- Otorrhea (if perforation occurred): Purulent discharge in the ear canal, often obscuring the view of the TM. A perforation may be visible.

III. Clinical Presentation of Otitis Media with Effusion (OME):

Asymptomatic: Often, children with OME do not have acute symptoms of pain or fever. It may be an incidental finding.

Hearing Loss: The most common symptom. Parents may notice:

- Child not responding to quiet sounds.

- Increased volume on TV/radio.

- Difficulty with speech development or articulation.

- Inattentiveness.

Aural Fullness or Popping: Older children/adults may describe a feeling of pressure or "plugged ear."

Otoscopic Findings for OME:

- Dull, Opaque, or Retracted TM: The eardrum may appear pulled inward.

- Fluid Level or Air Bubbles: May be visible behind the TM.

- Limited Mobility: Pneumatic otoscopy will show reduced mobility of the TM, but without the acute signs of inflammation (no bulging or significant erythema).

IV. Clinical Presentation of Chronic Suppurative Otitis Media (CSOM):

Chronic Otorrhea: Persistent or intermittent ear discharge (often mucoid or purulent) through a tympanic membrane perforation, lasting usually for more than 6 weeks.

Painless: Often no acute ear pain or fever, unless an acute exacerbation occurs.

Conductive Hearing Loss: Due to the perforation and changes in the middle ear.

Otoscopic Findings for CSOM:

- Tympanic Membrane Perforation: A visible hole in the eardrum.

- Mucosal Edema/Granulations: The middle ear mucosa may appear swollen or have granulation tissue.

- Discharge: Present in the ear canal, potentially obscuring the view of the middle ear.

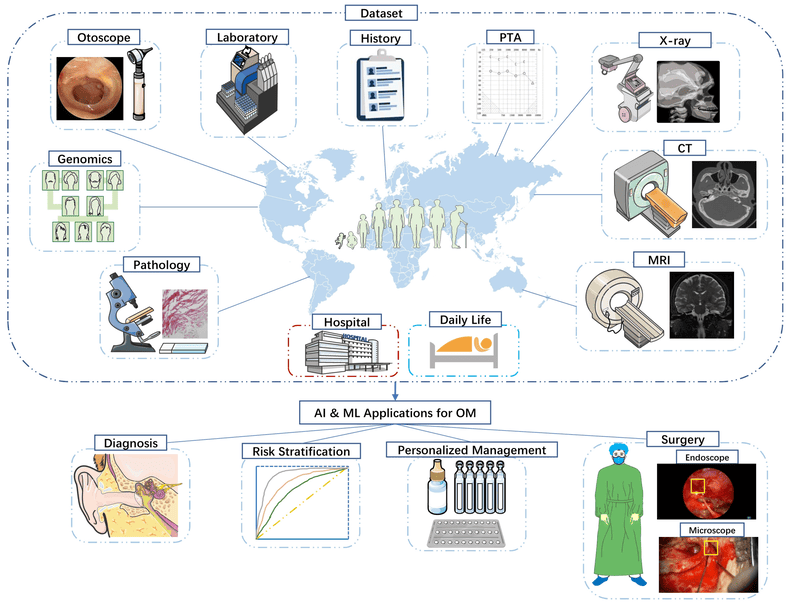

Diagnostic Approaches of Otitis Media

The accurate diagnosis of Otitis Media (OM), particularly Acute Otitis Media (AOM), relies primarily on a thorough clinical history and a careful physical examination using specialized tools. For AOM, the key is to identify middle ear effusion AND signs of acute inflammation.

I. Clinical History:

A detailed history is crucial and should include:

- Onset and Duration of Symptoms: Rapid onset is key for AOM.

- Specific Symptoms:

- Presence of ear pain (otalgia) and its characteristics.

- Fever, irritability, difficulty sleeping, decreased appetite, fussiness.

- Ear pulling/tugging (especially in infants).

- Recent or current upper respiratory tract infection (URTI) symptoms (cough, runny nose, congestion).

- Changes in hearing or speech development (for OME).

- Presence of ear discharge (otorrhea).

- Risk Factors: Daycare attendance, exposure to tobacco smoke, history of recurrent AOM, allergies, feeding practices.

- Previous Episodes: Number and frequency of prior OM episodes, and treatments received.

II. Physical Examination

Otoscopy: This is the most important diagnostic tool. A skilled examiner uses an otoscope to visualize the tympanic membrane (TM).

- Proper Technique:

- Stabilize the head (especially in children).

- Gently pull the auricle (pinna) up and back in adults, or down and back in children, to straighten the ear canal.

- Insert the speculum carefully to visualize the TM.

- Key Observations for AOM:

- Bulging of the TM: This is the most specific sign of AOM. The TM bows outwards due to pressure from the middle ear fluid.

- Erythema (Redness) of the TM: Indicates inflammation. Note that crying can also cause redness, so it must be evaluated in context.

- Opacity of the TM: The TM loses its normal translucent appearance and becomes cloudy or dull.

- Loss of Landmarks: Normal anatomical structures like the cone of light and the malleus handle become obscured.

- Key Observations for OME:

- TM is usually not red or bulging.

- Dull, opaque, or retracted TM.

- Fluid levels or air bubbles behind the TM may be visible.

- Key Observations for CSOM:

- Perforation of the TM.

- Otorrhea (purulent discharge) from the perforation.

- Middle ear mucosa may appear edematous or granulated.

Pneumatic Otoscopy: This technique is critical for assessing the mobility of the tympanic membrane.

- Method: A special otoscope head with an air bulb attached allows the clinician to introduce positive and negative pressure into the external ear canal.

- Interpretation:

- Normal TM: Moves inward with positive pressure and outward with negative pressure.

- TM with AOM: Shows absent or severely diminished mobility due to the pressure of fluid/pus behind it.

- TM with OME: Shows diminished mobility (often retracted) but without the acute inflammatory signs of AOM.

- Perforated TM: No movement with pressure changes.

- Significance: Pneumatic otoscopy is considered more reliable than visual inspection alone, especially for distinguishing AOM from OME or a normal ear.

III. Adjunctive Diagnostic Tests:

These tests are not typically used for routine diagnosis of AOM but can be valuable in specific situations, especially for OME or when otoscopy is difficult.

Tympanometry:

- Method: An objective test that measures the compliance (mobility) of the tympanic membrane and the air pressure in the middle ear. A probe is placed snugly in the ear canal.

- Interpretation:

- Type A Tympanogram (Normal): Peak compliance at or near 0 daPa, indicating a healthy, mobile TM and normal middle ear pressure.

- Type B Tympanogram (Flat): No peak, indicating severely reduced or absent TM mobility, consistent with fluid in the middle ear (OME or AOM) or a perforated TM.

- Type C Tympanogram: Peak compliance shifted to negative pressure (e.g., < -150 daPa), indicating significant negative pressure in the middle ear, often associated with Eustachian tube dysfunction and sometimes preceding OME.

- Significance: Useful for confirming the presence of middle ear effusion when pneumatic otoscopy is equivocal or difficult. It cannot distinguish between AOM and OME on its own but can confirm effusion.

Acoustic Reflectometry:

- Method: Measures the reflection of sound waves off the eardrum. Fluid in the middle ear changes the acoustic impedance, leading to a different reflection pattern.

- Significance: Can be used as a screening tool, but less precise than tympanometry or pneumatic otoscopy. Not widely used clinically for definitive diagnosis.

Cultures:

- Middle Ear Fluid Culture: Obtained via tympanocentesis (puncture of the TM to aspirate fluid).

- Indications: Reserved for severe cases, immunocompromised patients, treatment failure, or when an unusual organism is suspected. Not routine.

- Ear Canal Discharge Culture: For CSOM, to identify causative organisms and guide antibiotic choice.

IV. Diagnostic Criteria for AOM:

According to major medical guidelines (e.g., American Academy of Pediatrics), the diagnosis of AOM requires:

- Rapid onset of signs and symptoms.

- Presence of middle ear effusion (MEE), as indicated by:

- Bulging of the tympanic membrane.

- Limited or absent mobility of the TM (pneumatic otoscopy).

- Air-fluid level behind the TM.

- Otorrhea.

- Signs and symptoms of middle ear inflammation, as indicated by:

- Distinct erythema (redness) of the TM.

- Distinct otalgia (ear pain) that interferes with activity or sleep.

Differential Diagnosis

When a patient presents with symptoms suggestive of ear problems, particularly ear pain, fussiness, or hearing concerns, it's crucial to consider conditions other than Otitis Media.

I. Conditions Primarily Affecting the External Ear:

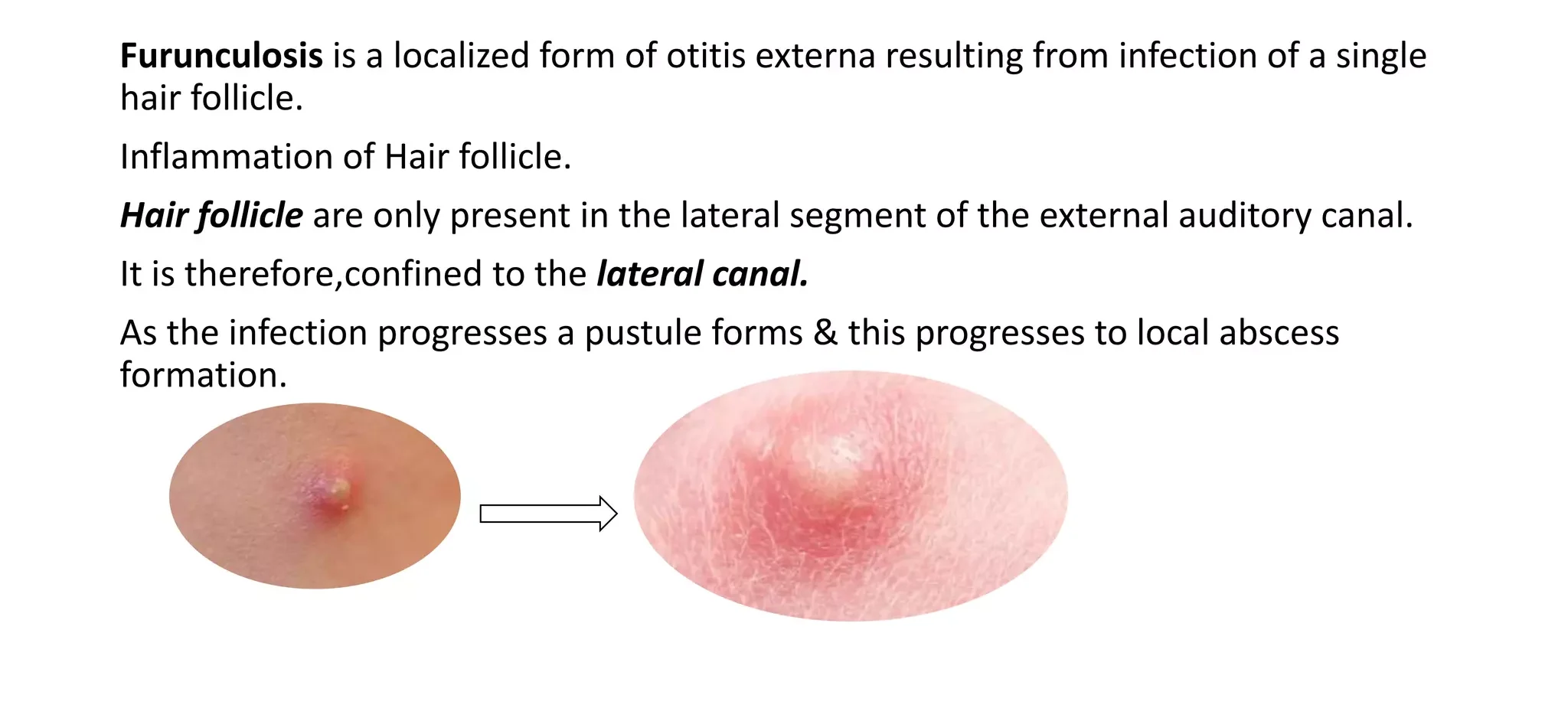

Otitis Externa (Swimmer's Ear): Inflammation or infection of the external ear canal.

- Distinguishing Features:

- Pain aggravated by manipulation of the tragus or auricle.

- Often associated with water exposure, trauma, or foreign body.

- Ear canal may be swollen, red, and have discharge.

- Tympanic membrane is typically normal unless the infection is severe enough to obscure the view.

- No systemic symptoms like fever unless severe.

Foreign Body in the Ear Canal: Objects (beads, insects, cotton) lodged in the ear canal.

- Distinguishing Features:

- Sudden onset of pain, irritation, or hearing loss.

- Visible foreign body on otoscopy.

- No signs of middle ear infection (TM normal unless injured by foreign body).

Impacted Cerumen (Earwax): Excessive earwax blocking the ear canal.

- Distinguishing Features:

- Gradual onset of hearing loss or a feeling of fullness.

- No pain unless the wax is pushing against the eardrum or causing irritation.

- Visible impacted cerumen on otoscopy, often completely obscuring the TM.

Trauma to the Ear Canal or Tympanic Membrane: Injury from cotton swabs, foreign objects, or slaps to the ear.

- Distinguishing Features:

- Clear history of trauma.

- Pain, bleeding, or possible TM perforation.

II. Conditions That Cause Referred Otalgia (Ear Pain Originating Elsewhere):

Pain can be referred to the ear from various structures innervated by cranial nerves that also supply the ear (CN V, VII, IX, X) and cervical nerves. This is particularly important when otoscopy is normal.

Dental Problems: Toothache, dental abscess, temporomandibular joint (TMJ) dysfunction.

- Distinguishing Features:

- Pain aggravated by chewing or jaw movement.

- Evidence of dental pathology (caries, gum inflammation).

- Normal otoscopy.

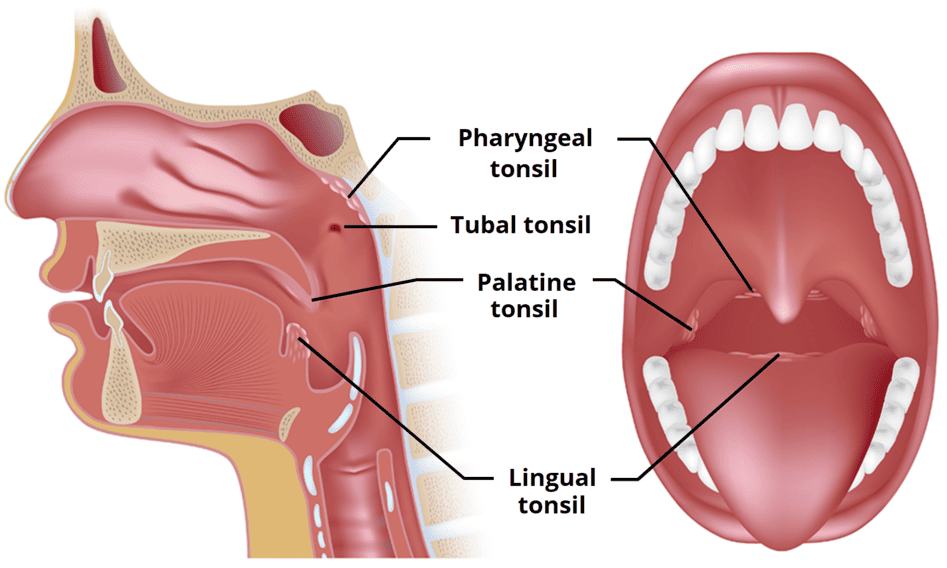

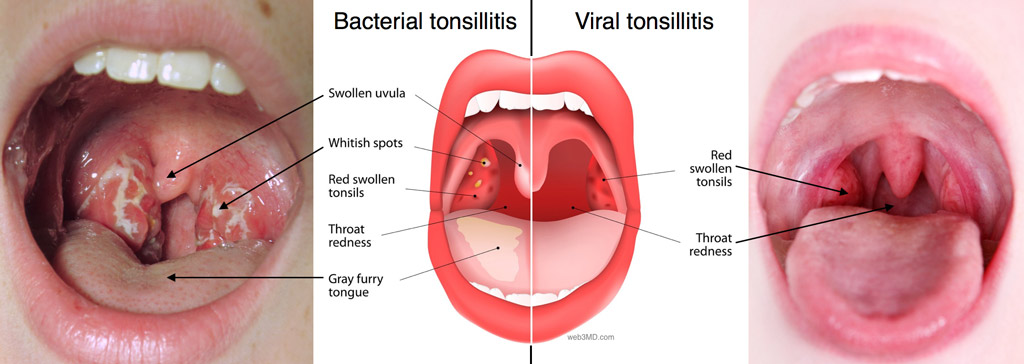

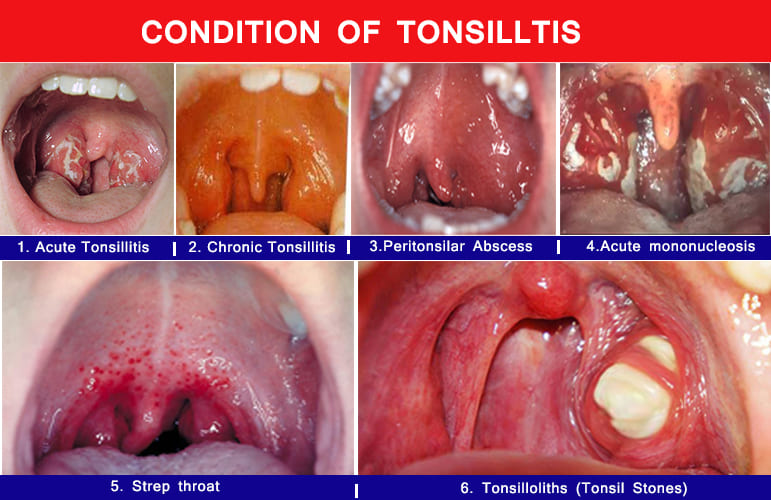

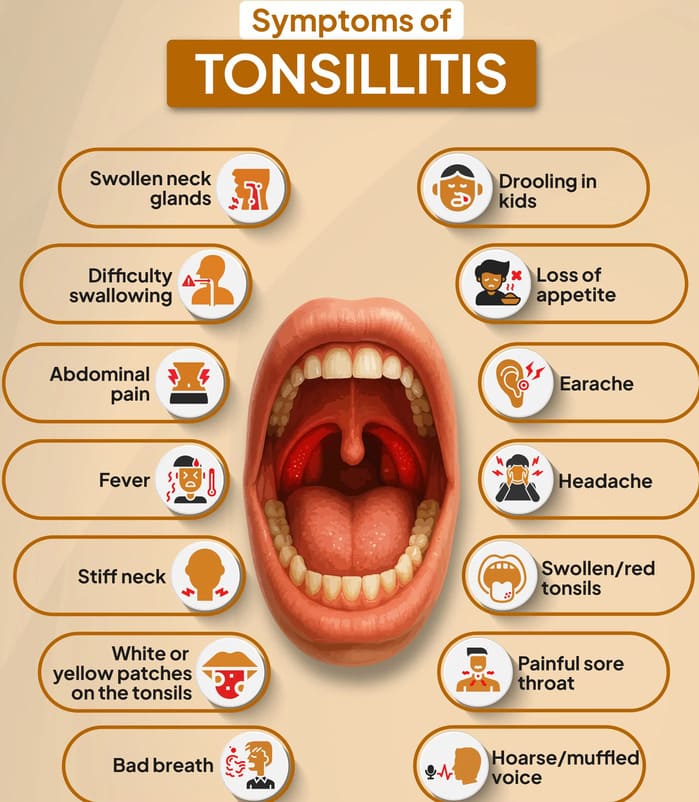

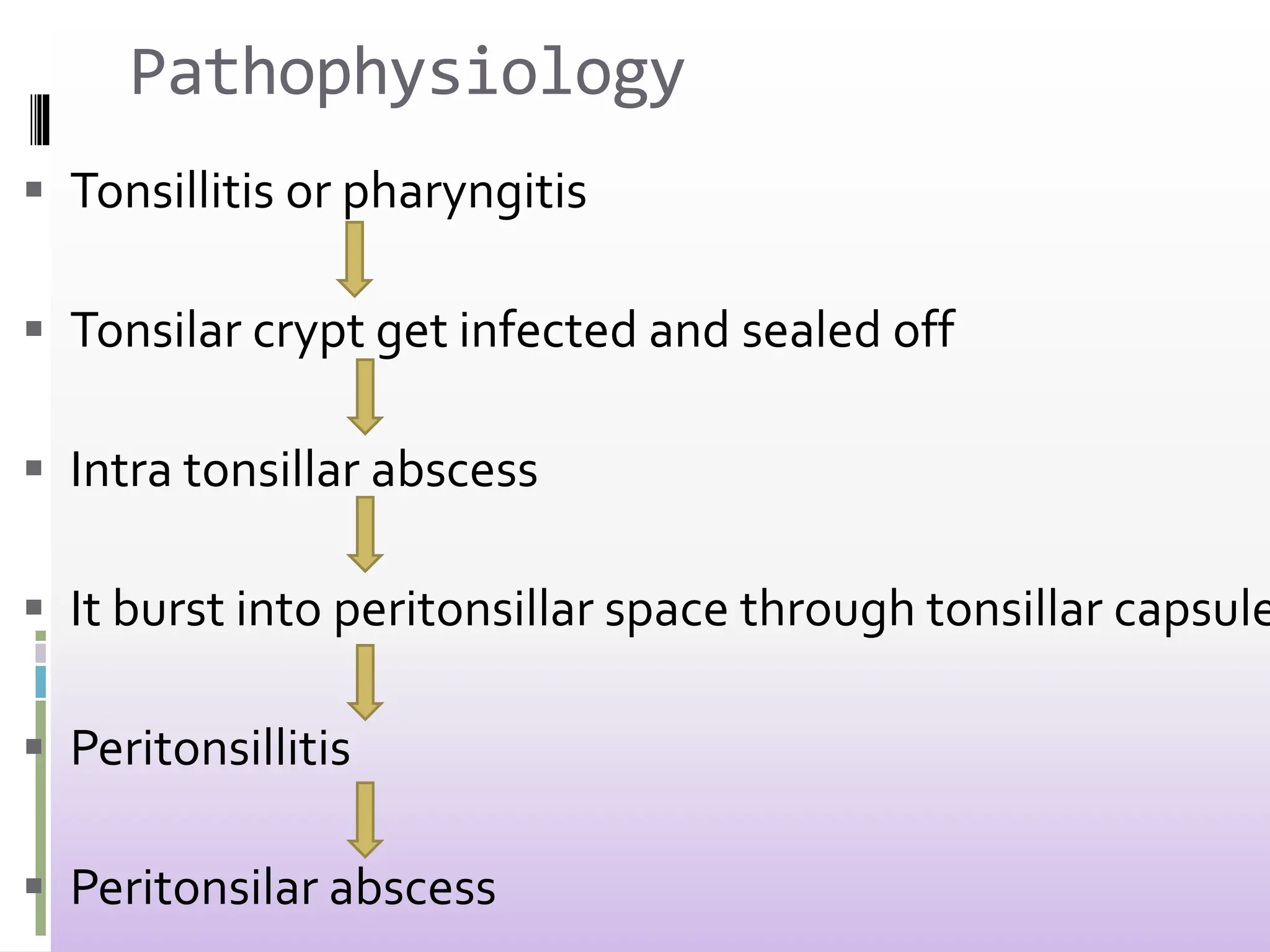

Pharyngitis/Tonsillitis: Sore throat, inflammation of the tonsils or pharynx.

- Distinguishing Features:

- Prominent sore throat, pain with swallowing.

- Red, inflamed pharynx/tonsils (possibly exudate).

- Normal otoscopy.

Parotitis (e.g., Mumps): Inflammation of the parotid gland.

- Distinguishing Features:

- Swelling and tenderness in the preauricular or submandibular area.

- Pain with eating or jaw movement.

- Normal otoscopy.

Temporomandibular Joint (TMJ) Dysfunction: Pain or dysfunction of the jaw joint.

- Distinguishing Features:

- Pain with chewing, jaw movement, or clenching.

- Clicking or popping sensation in the jaw.

- Tenderness over the TMJ.

- Normal otoscopy.

Cervical Lymphadenitis: Swollen, tender lymph nodes in the neck.

- Distinguishing Features:

- Palpable, tender lymph nodes.

- Pain may radiate to the ear.

- Normal otoscopy.

Mastoiditis: Inflammation/infection of the mastoid bone (a complication of OM, but can be a differential in its early stages).

- Distinguishing Features:

- Postauricular pain, tenderness, and swelling.

- Protrusion of the auricle.

- Usually accompanied by signs of AOM.

III. Other Systemic/Non-Ear Related Conditions:

Upper Respiratory Tract Infection (URTI) / Common Cold: Viral infection causing nasal congestion, cough, sore throat.

- Distinguishing Features:

- Often precedes OM.

- May cause transient ear fullness or mild discomfort due to Eustachian tube inflammation, but without signs of middle ear effusion or acute inflammation on otoscopy.

Teething (in infants): Eruption of primary teeth.

- Distinguishing Features:

- Fussiness, drooling, gnawing on objects.

- Red, swollen gums.

- Normal otoscopy.

Management and Treatment of Otitis Media

The management of Otitis Media (OM) is tailored to the specific type of OM, the severity of symptoms, the age of the patient, and the presence of any complications or recurrent episodes. The primary goals are to alleviate pain, eradicate infection, prevent complications, and preserve hearing.

I. Management of Acute Otitis Media (AOM):

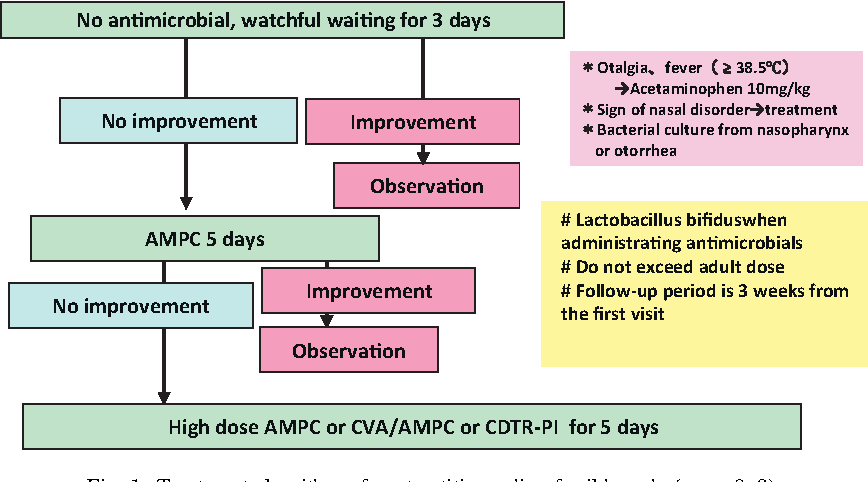

The approach to AOM involves a balance between antibiotic use and symptomatic relief, often incorporating a "watchful waiting" approach in specific scenarios.

Pain Management:

- First-line: Acetaminophen (paracetamol) or Ibuprofen are crucial for pain and fever relief.

- Rationale: Even if antibiotics are prescribed, pain relief is immediate and vital for patient comfort.

- Intervention: Advise parents to administer pain medication promptly.

Antibiotic Therapy:

- General Principle: While AOM is often bacterial, many cases resolve spontaneously, especially in older children. However, antibiotics are indicated in specific situations.

- Indications for Immediate Antibiotics:

- Children < 6 months of age. (High risk of complications)

- Children 6 months to 2 years with definite AOM. (Higher risk of complications, difficulty in assessing symptoms)

- Children > 2 years with definite AOM and severe symptoms (e.g., moderate-to-severe otalgia, otalgia for at least 48 hours, or temperature ≥39°C [102.2°F]).

- AOM with otorrhea (ear discharge).

- Immunocompromised patients or those with underlying conditions.

- "Watchful Waiting" (Observation) Option:

- Indications: May be offered to children aged 6 months to 2 years with unilateral AOM and non-severe symptoms (mild otalgia, temperature <39°C), OR children ≥ 2 years with unilateral or bilateral AOM and non-severe symptoms.

- Mechanism: Pain control is initiated, and parents are instructed to return or start antibiotics if symptoms do not improve within 48-72 hours or worsen.

- Rationale: Reduces unnecessary antibiotic use, which contributes to antibiotic resistance.

- First-Line Antibiotics:

- Amoxicillin: High-dose (80-90 mg/kg/day divided twice daily) is the drug of choice for most uncomplicated AOM, covering S. pneumoniae and H. influenzae.

- Amoxicillin-Clavulanate (Augmentin): Used if the child has received amoxicillin in the past 30 days, has concurrent conjunctivitis, or if there's suspicion of beta-lactamase-producing bacteria (e.g., resistant H. influenzae or M. catarrhalis).

- Alternative for Penicillin Allergy: Cefdinir, Cefuroxime, Cefpodoxime, Ceftriaxone (IM/IV), or Azithromycin (less effective against S. pneumoniae).

- Duration of Therapy:

- Children < 2 years: 10 days.

- Children 2-5 years: 7 days.

- Children ≥ 6 years: 5-7 days.

- Severe AOM in any age: 10 days.

Follow-up:

- After Watchful Waiting: If symptoms persist or worsen, antibiotics should be started.

- After Antibiotics: A follow-up visit is often recommended, especially for young children or those with recurrent AOM, to ensure resolution of symptoms and middle ear effusion.

II. Management of Otitis Media with Effusion (OME):

OME typically does not require antibiotics unless it progresses to AOM, as it is generally sterile fluid.

- Watchful Waiting:

- Principle: Most OME resolves spontaneously within 3 months.

- Intervention: Monitor for hearing loss and speech development.

- Rationale: Avoids unnecessary medical intervention.

- Hearing Assessment:

- Indication: If OME persists for 3 months or longer, a hearing test should be performed, especially in children with speech, language, or learning concerns.

- Intervention: Audiology referral.

III. Management of Recurrent Acute Otitis Media (RAOM) and Persistent OME:

- Antibiotic Prophylaxis:

- Principle: Low-dose daily antibiotics to prevent recurrent infections.

- Indications: Controversial and generally discouraged due to concerns about antibiotic resistance, but may be considered in specific cases where benefits outweigh risks and tubes are not an option.

- Intervention: Daily low-dose amoxicillin or sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim.

- Adenoidectomy:

- Principle: Removal of enlarged adenoids, which can obstruct the Eustachian tube.

- Indications: May be considered for children with RAOM or OME who also have adenoidal hypertrophy and persistent symptoms despite other interventions. Often performed concurrently with tube insertion.

IV. Surgical Management for Otitis Media:

Surgical interventions are typically reserved for cases of recurrent AOM, persistent OME causing hearing loss, or chronic forms of OM that do not respond to medical management.

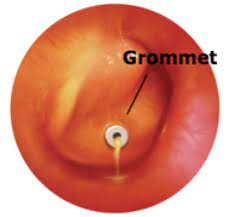

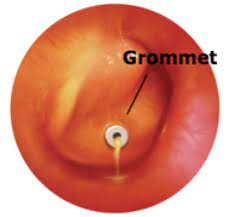

Grommets (Tympanostomy Tubes): Tiny tubes inserted through the eardrum to help drain fluid and equalize pressure.

Grommets (Tympanostomy Tubes): Tiny tubes inserted through the eardrum to help drain fluid and equalize pressure.

- Indications: Recurrent AOM (e.g., 3 episodes in 6 months or 4 in 12 months with OME present), persistent OME (≥ 3 months) with documented hearing loss or developmental concerns, AOM in children with structural abnormalities (e.g., cleft palate).

- Nursing Considerations (Post-Grommet Insertion):

- Water Precautions: Emphasize strict avoidance of water entering the ear canal (e.g., during bathing, swimming). Use earplugs or headbands as advised by the surgeon. This prevents bacteria from entering the middle ear through the tube.

- Monitor for Otorrhea: Watch for any drainage from the ear, which could indicate a tube blockage or infection. Report persistent or purulent drainage.

- Pain Management: Administer prescribed analgesics, though post-operative pain is usually mild.

- Hearing Assessment: Reassure parents that hearing should improve immediately.

- Educate Family: Provide clear instructions on tube care, signs of complications, and when to seek medical attention.

- Follow-up: Explain the importance of regular follow-up with the ENT specialist to monitor tube function and natural extrusion.

Myringotomy: A surgical procedure making a tiny incision in the eardrum to relieve pressure and drain excess fluid from the middle ear. Can be followed by grommet insertion.

- Indications: Acute, severe AOM with bulging TM, intractable pain, or impending rupture; often performed as a precursor to tube insertion.

- Nursing Considerations (Post-Myringotomy):

- Pain Relief: Administer analgesics as needed.

- Monitor for Drainage: Observe for serous or purulent drainage. If tubes are not inserted, the incision typically heals quickly.

- Positioning: Encourage lying on the affected side (if comfortable) to facilitate drainage.

- Patient Education: Advise on keeping the ear dry if tubes are not inserted.

Tympanotomy: A surgical opening made in the eardrum (tympanic membrane) to promote drainage of infected fluid from the middle ear. Surgical tubes are typically implanted to ensure ongoing drainage. It is done when there is scarring or minor damage to the tympanic membrane, in cases of deafness, or hearing impairment.

- Indications: Similar to myringotomy with tube insertion, specifically when drainage and long-term ventilation are required, especially if the TM has some existing pathology.

- Nursing Considerations (Post-Tympanotomy with Tubes):

- Similar to grommet insertion: strict water precautions, monitoring for discharge, pain management, and comprehensive family education regarding tube care and potential complications.

- Emphasize that the primary goal is drainage and ventilation, aiming to prevent recurrence and improve hearing.

Myringoplasty: Surgical procedure to repair a hole in the eardrum by placing a graft (tissue from the patient or synthetic material).

- Indications: Persistent tympanic membrane perforation (e.g., from CSOM, trauma) that has failed to heal spontaneously, causing hearing loss or recurrent infections.

- Nursing Considerations (Post-Myringoplasty):

- Head of Bed Elevation: Maintain semi-Fowler's position to reduce pressure.

- Avoid Nose Blowing/Sneezing: Advise the patient to avoid forceful nose blowing, sneezing (sneeze with mouth open), and straining (e.g., during defecation) to prevent dislodging the graft.

- Water Precautions: Absolutely no water in the ear until cleared by the surgeon.

- Monitor for Dizziness/Vertigo: Report any new onset of severe dizziness.

- Pain Management: Administer prescribed analgesics.

- Strict Activity Restrictions: Avoid heavy lifting, bending, and strenuous activity for several weeks.

- Patient Education: Reinforce post-operative instructions carefully, explaining the importance of protecting the healing graft.

Tympanoplasty: Repair of damaged ossicles (small bones of the middle ear) by replacing them with a piece of bone or prosthesis, often performed in conjunction with myringoplasty.

- Indications: Ossicular chain discontinuity or erosion, usually due to CSOM, leading to conductive hearing loss.

- Nursing Considerations (Post-Tympanoplasty):

- All considerations for Myringoplasty apply (head elevation, avoiding nose blowing/straining, water precautions, activity restrictions, pain management).

- Emphasis on Hearing Improvement: Discuss with the patient that hearing improvement may not be immediate and can take time as swelling subsides.

- Monitor for Facial Nerve Dysfunction: Very rare, but swelling can sometimes affect the facial nerve. Assess for facial symmetry and movement.

- Vertigo/Nausea: More common with ossicular surgery; administer antiemetics as prescribed.

V. General Nursing Care for Otitis Media:

- Pain Management: As mentioned, apply hot water bag over the ear with the child lying on the affected side (during pain attacks) or ice bag over the affected ear (between pain attacks) may reduce discomfort and edema.

- Aural Hygiene (for drained ear/otorrhea):

- The external canal should be frequently cleaned using sterile cotton swabs (dry or soaked in hydrogen peroxide, if approved by physician).

- Prevent excoriation of the outer ear by frequent cleansing and application of a protective barrier (e.g., zinc oxide) to the area of exudate.

- In case of any discharge, dry the ear by ear wicking (make a wick using a cotton swab and gently clean the pus from the ear).

- Hydration: Encourage or give plenty of oral fluids, especially if the patient has fever.

- Rest: Rest the patient in bed during acute phases of illness.

- Education and Emotional Support:

- Educate family about the child's care, medication administration, and potential complications (e.g., conductive hearing loss).

- Provide emotional support to the child and his family, addressing their concerns and anxieties about pain, hearing loss, and surgical procedures.

Potential Complications of Otitis Media

Complications of Otitis Media (OM) can be categorized into intratemporal (within the temporal bone) and intracranial (within the skull) complications.

I. Intratemporal Complications (Within the Temporal Bone):

These complications affect structures within or immediately adjacent to the middle ear.

- Hearing Loss:

- Conductive Hearing Loss: This is the most common complication, especially with Otitis Media with Effusion (OME) and Chronic Suppurative Otitis Media (CSOM).

- Mechanism: Fluid in the middle ear (OME/AOM) or damage to the tympanic membrane/ossicles (CSOM) obstructs the transmission of sound waves to the inner ear.

- Impact: Can range from mild to moderate and, if prolonged in children, can affect speech and language development, academic performance, and behavior.

- Sensorineural Hearing Loss: Less common, but can occur due to spread of infection or toxins to the inner ear, or rarely as a result of direct trauma during surgery.

- Tympanic Membrane Perforation: Increased pressure from fluid/pus in the middle ear can cause the eardrum to rupture.

- Outcome: Most acute perforations heal spontaneously. However, chronic perforations can persist, leading to CSOM and conductive hearing loss.

- Tympanosclerosis: Formation of dense, white plaques of hyaline and calcium deposits on the tympanic membrane (and sometimes in the middle ear mucosa) as a result of chronic inflammation.

- Impact: Can lead to a stiffened eardrum and ossicles, potentially causing conductive hearing loss. Usually benign, but extensive tympanosclerosis can impair hearing significantly.

- Atelectasis of the Tympanic Membrane and Retraction Pockets: Prolonged Eustachian tube dysfunction leads to persistent negative pressure in the middle ear, causing the eardrum to retract inwards.

- Impact: Can create "retraction pockets" where debris can accumulate, predisposing to cholesteatoma formation. Severe atelectasis can lead to adhesions and ossicular erosion.

- Cholesteatoma: An abnormal skin growth (keratinizing squamous epithelium) in the middle ear or mastoid. It can form from a deep retraction pocket or a perforation edge. It is not cancerous but is locally destructive.

- Impact: Can erode bone (ossicles, mastoid bone, labyrinth, tegmen tympani), leading to hearing loss, dizziness, facial nerve paralysis, and intracranial complications. Requires surgical removal.

- Mastoiditis: Spread of infection from the middle ear into the mastoid air cells, causing inflammation and destruction of the mastoid bone.

- Signs: Postauricular pain, tenderness, swelling, erythema, and outward displacement of the auricle.

- Severity: Can be acute (early inflammation) or chronic (with bone erosion). Requires aggressive antibiotic therapy and often surgical drainage (mastoidectomy).

- Labyrinthitis: Inflammation of the labyrinth (inner ear) due to the spread of infection or toxins from the middle ear.

- Signs: Sudden onset of vertigo, nausea, vomiting, nystagmus, and sometimes sensorineural hearing loss.

- Severity: Can be serous (sterile inflammation) or suppurative (bacterial infection), with suppurative labyrinthitis having a worse prognosis for hearing.

- Facial Nerve Paralysis: The facial nerve (CN VII) passes through the temporal bone. Inflammation, edema, or direct erosion by infection (especially cholesteatoma) can compress or damage the nerve.

- Signs: Unilateral weakness or paralysis of facial muscles (e.g., inability to close eye, drooping mouth).

- Outcome: Can be temporary or permanent.

II. Intracranial Complications (Within the Skull):

These are rare but very serious complications that occur when the infection spreads beyond the temporal bone into the cranial cavity.

- Meningitis: Spread of bacteria from the middle ear or mastoid into the meninges (membranes surrounding the brain and spinal cord).

- Signs: High fever, severe headache, neck stiffness (nuchal rigidity), photophobia, altered mental status.

- Severity: A life-threatening emergency requiring immediate aggressive antibiotic treatment.

- Brain Abscess: Formation of a collection of pus within the brain parenchyma, usually in the temporal lobe or cerebellum, due to direct spread from the temporal bone.

- Signs: Headache, fever, focal neurological deficits (e.g., weakness, speech difficulties), seizures, altered consciousness.

- Severity: Life-threatening, requiring both antibiotics and surgical drainage.

- Epidural Abscess: Collection of pus between the dura mater and the temporal bone.

- Signs: Often subtle, may present with headache and fever. Can precede meningitis or brain abscess.

- Subdural Abscess: Collection of pus between the dura mater and arachnoid mater.

- Signs: Similar to epidural abscess but potentially more severe and rapidly progressive.

- Lateral Sinus Thrombosis: Formation of a blood clot within the lateral (sigmoid) sinus, a major venous channel draining blood from the brain, due to inflammation or infection from the mastoid.

- Signs: Picket-fence fever (spiking temperature), severe headache, nausea, vomiting, papilledema. Can lead to septic emboli.

- Severity: Serious, requiring antibiotics and sometimes anticoagulation or surgical intervention.

III. Long-Term Sequelae (General Impacts):

- Speech and Language Delay: Persistent conductive hearing loss, especially during critical periods of language acquisition, can lead to delayed speech and language development, poor articulation, and difficulties with phonological awareness.

- Impact: Can affect academic performance and social development.

- Balance Problems: Involvement of the inner ear (labyrinth) or persistent middle ear pressure issues.

- Signs: Dizziness, unsteadiness, clumsiness.

Prevention Strategies of Otitis Media

Prevention strategies for Otitis Media aim to reduce the incidence of initial infections, prevent recurrence, and mitigate the development of chronic conditions or complications. These strategies can be broadly categorized into vaccinations, lifestyle modifications, and medical interventions.

I. Vaccinations:

Immunizations are one of the most effective public health interventions for preventing infectious diseases, including OM.

- Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine (PCV): Targets Streptococcus pneumoniae, a leading bacterial cause of AOM.

- Impact: Routine childhood immunization with PCV (e.g., PCV13, PCV15, PCV20) has significantly reduced the incidence of AOM and invasive pneumococcal disease.

- Recommendation: Universal vaccination of infants and young children according to national immunization schedules.

- Influenza Vaccine (Flu Shot): Prevents influenza virus infection, which is a common precursor to bacterial AOM.

- Impact: Reduces the overall burden of respiratory tract infections, thereby decreasing the risk of secondary bacterial ear infections.

- Recommendation: Annual influenza vaccination for all children aged 6 months and older.

- Measles, Mumps, and Rubella (MMR) Vaccine: Prevents viral infections that can sometimes lead to OM (e.g., mumps can cause parotitis and sometimes ear involvement).

- Recommendation: Routine childhood vaccination.

II. Lifestyle and Environmental Modifications:

These strategies focus on reducing exposure to risk factors and promoting overall health.

- Avoidance of Tobacco Smoke Exposure (Passive Smoking): Exposure to secondhand smoke irritates the Eustachian tube and respiratory mucosa, increasing inflammation and impairing mucociliary clearance, making children more susceptible to infections.

- Breastfeeding: Breast milk provides antibodies and immunoglobulins that protect infants from various infections, including those that cause OM. The act of breastfeeding itself (positioning, suction) may also positively influence Eustachian tube function compared to bottle feeding.

- Avoidance of Bottle Propping and Supine Bottle Feeding: When infants drink from a bottle while lying flat, milk can flow into the Eustachian tube, irritating it and potentially introducing bacteria.

- Minimizing Pacifier Use (for older infants/toddlers): While pacifier use is often recommended for SIDS prevention in infants, some studies suggest that frequent pacifier use in older infants and toddlers (e.g., beyond 6-12 months) might alter Eustachian tube function and slightly increase OM risk.

- Good Hand Hygiene: Reduces the spread of respiratory viruses and bacteria that can lead to OM.

- Childcare Setting: Children in large group childcare settings are exposed to more infectious agents.

III. Medical and Surgical Interventions (Preventive):

While these are treatments, they also serve a preventive role by reducing future episodes or complications.

- Management of Allergies/Allergic Rhinitis: Allergies can cause inflammation and congestion of the nasal passages and Eustachian tubes, predisposing to OM.

- Addressing Eustachian Tube Dysfunction: Conditions causing chronic Eustachian tube dysfunction (e.g., enlarged adenoids, structural abnormalities) lead to negative middle ear pressure and fluid accumulation.

- Recommendation:

- Adenoidectomy: Surgical removal of adenoids can improve Eustachian tube function and reduce recurrent AOM in some children, especially when combined with tympanostomy tube insertion.

- Tympanostomy Tube Insertion (Grommets): For children with recurrent AOM or persistent OME, tubes ventilate the middle ear, prevent fluid accumulation, and significantly reduce the frequency of acute infections and associated hearing loss.

- Antibiotic Prophylaxis (Limited Role): Low-dose daily antibiotics to prevent recurrent bacterial AOM.

Nursing Diagnoses and Interventions

Nursing Diagnosis 1: Acute Pain

Related to inflammation and pressure in the middle ear.

- Goal: Patient will experience reduced pain and discomfort.

| Intervention |

Rationale/Detail |

| Assess Pain |

Use an age-appropriate pain scale (e.g., FLACC for infants/non-verbal, Wong-Baker FACES for young children, numeric scale for older children/adults) to quantify pain severity. |

| Administer Analgesics/Antipyretics |

Provide prescribed acetaminophen (paracetamol) or ibuprofen regularly to manage pain and fever. |

| Apply Local Comfort Measures |

- For acute pain: Apply a warm compress or hot water bag over the affected ear (with the child lying on that side) to promote vasodilation and comfort.

- Between pain attacks/to reduce edema: Apply an ice pack over the affected ear.

|

| Positioning |

Encourage resting in a position of comfort; semi-Fowler's can help reduce pressure. |

| Distraction |

Use age-appropriate distraction techniques for children (e.g., stories, toys, quiet play). |

| Educate Parents |

Instruct on proper dosage and frequency of pain medication, and when to seek further medical attention if pain worsens or is unrelieved. |

Nursing Diagnosis 2: Risk for Infection

Related to presence of fluid in the middle ear, surgical interventions, or tympanic membrane perforation.

- Goal: Patient will remain free from signs and symptoms of worsening infection or secondary infection.

| Intervention |

Rationale/Detail |

| Monitor for Signs of Infection |

Regularly assess for fever, increased pain, purulent ear discharge, redness/swelling behind the ear, or worsening general condition. |

| Administer Antibiotics |

Give prescribed oral or topical antibiotics (e.g., eardrops) as directed, ensuring the full course is completed even if symptoms improve. |

| Aural Hygiene (for perforated or drained ear) |

- Gently clean the external ear canal frequently with sterile cotton swabs (dry or soaked in prescribed solution like hydrogen peroxide if indicated) to remove discharge.

- Prevent excoriation of the outer ear by cleansing and applying a protective barrier (e.g., zinc oxide cream).

- For active drainage, use ear wicking (insert a cotton wick into the ear canal to absorb pus) and change frequently.

|

| Water Precautions (especially post-surgery/with tubes/perforation) |

- Strictly advise to avoid water entering the middle ear during bathing, showering, or swimming.

- Educate on the use of earplugs or a bathing cap/cotton balls coated with petroleum jelly for protection.

|

| Promote Hand Hygiene |

Emphasize frequent handwashing for the patient and caregivers. |

| Educate on Signs of Complications |

Instruct parents on specific signs that indicate a worsening infection or potential complications (e.g., mastoiditis, facial paralysis, severe headache) and when to seek urgent medical care. |

Nursing Diagnosis 3: Disturbed Sensory Perception: Auditory

Related to fluid in the middle ear, tympanic membrane changes, or ossicular damage, leading to conductive hearing loss.

- Goal: Patient/family will understand the temporary nature of hearing loss and strategies to facilitate communication; long-term hearing impairment will be minimized.

| Intervention |

Rationale/Detail |

| Assess Hearing Function |

Observe signs of hearing difficulty (e.g., child not responding, turning up TV volume, misunderstanding speech). Encourage formal audiology assessment if OME persists or hearing loss is suspected. |

| Facilitate Communication |

- Speak clearly, slowly, and at a normal volume (avoid shouting).

- Face the patient when speaking to allow for lip-reading and visual cues.

- Reduce background noise.

- Rephrase rather than just repeating if misunderstanding occurs.

- Use visual aids as appropriate.

|

| Educate Parents |

Explain that hearing loss from OM is often temporary, but prolonged loss can affect development. Discuss the importance of follow-up audiology if OME persists. |

| Post-Surgical Monitoring |

For patients with tympanostomy tubes, explain that hearing should improve quickly after fluid drainage. |

Nursing Diagnosis 4: Inadequate health Knowledge

Regarding the disease process, treatment regimen, potential complications, and prevention strategies.

- Goal: Patient/family will verbalize understanding of OM, its management, and preventative measures.

| Intervention |

Rationale/Detail |

| Provide Clear Explanations |

Explain Otitis Media in simple, understandable terms (cause, symptoms, expected course). |

| Review Treatment Plan |

Go over medication names, dosages, frequency, duration, and potential side effects. Emphasize completing the full course of antibiotics. |

| Discuss Surgical Procedures |

If applicable, explain the purpose of grommets, myringotomy, etc., what to expect pre- and post-operatively, and specific care instructions (e.g., water precautions). |

| Educate on Prevention |

Review strategies such as vaccination, breastfeeding benefits, avoiding secondhand smoke, and good hand hygiene. |

| Highlight Complications |

Clearly explain potential complications and specific signs requiring immediate medical attention. |

| Provide Written Materials |

Offer brochures, handouts, or reliable websites for further information. |

| Encourage Questions |

Create an open environment for the patient and family to ask questions and express concerns. |

Nursing Diagnosis 5: Excessive Anxiety

Related to pain, potential for hearing loss, surgical procedures, or impact on child's development.

- Goal: Patient/family will express reduced anxiety and fear, and participate effectively in care decisions.

| Intervention |

Rationale/Detail |

| Active Listening |

Listen to the patient's and family's concerns, fears, and questions without judgment. |

| Provide Reassurance |

Offer realistic reassurance about the typical course of OM and the effectiveness of treatment. |

| Educate and Empower |

Increased knowledge often reduces anxiety. Provide comprehensive information as per "Deficient Knowledge" diagnosis. |

| Involve in Decision-Making |

For older children and parents, involve them in shared decision-making regarding watchful waiting vs. antibiotics, or surgical options. |

| Therapeutic Play |

For children, use play therapy to explain procedures and alleviate fears. |

| Support Resources |

Offer connections to support groups or counseling if significant anxiety or stress is identified. |

Nursing Diagnosis 6: Risk for Delayed Child Development

Related to persistent hearing loss impacting speech and language acquisition.

- Goal: Identify and minimize developmental delays related to hearing loss.

| Intervention |

Rationale/Detail |

| Early Identification of OME |

Encourage routine screening for OME and hearing assessments, especially in children at high risk or with persistent OME. |

| Monitor Milestones |

Regularly assess the child's speech, language, and overall developmental milestones. |

| Referrals |

If persistent OME and hearing loss are identified, facilitate referrals to audiologists, speech-language pathologists, and developmental specialists. |

| Educate on Impact |

Explain to parents how even mild to moderate hearing loss can affect learning and communication. |

| Promote Intervention |

Advocate for timely surgical intervention (e.g., tympanostomy tubes) if indicated to restore hearing and prevent long-term delays. |

Nursing Diagnosis 7: Impaired Social Interaction

Related to communication difficulties due to hearing loss.

- Goal: Patient will engage in social interactions more effectively, with strategies to overcome communication barriers.

| Intervention |

Rationale/Detail |

| Address Hearing Loss |

Implement strategies as per "Disturbed Sensory Perception: Auditory" to improve the child's ability to hear and understand. |

| Encourage Peer Interaction |

Facilitate opportunities for social play and interaction, while supporting the child in communicating. |

| Educate Teachers/Caregivers |

Inform teachers and childcare providers about the child's hearing status and strategies to support them in the classroom or group setting (e.g., preferential seating, speaking clearly). |

| Build Self-Esteem |

Reinforce the child's strengths and accomplishments to build confidence, which can positively impact social engagement. |

Nursing Diagnosis 8: Hyperthermia

Related to inflammatory process (fever).

- Goal: Patient will maintain normothermia.

| Intervention |

Rationale/Detail |

| Monitor Temperature |

Assess body temperature regularly (e.g., every 4 hours or as needed). |

| Administer Antipyretics |

Provide prescribed acetaminophen or ibuprofen to reduce fever. |

| Promote Hydration |

Encourage plenty of oral fluids to prevent dehydration associated with fever. |

| Maintain Comfortable Environment |

Keep the patient in a cool, comfortable environment; avoid overdressing. |

| Cooling Measures |

If fever is very high, consider tepid sponging (if tolerated and not causing shivering) in conjunction with antipyretics. |

| Educate Parents |

Explain how to manage fever at home and when to seek medical attention for persistent or very high fever. |