Conjunctivitis

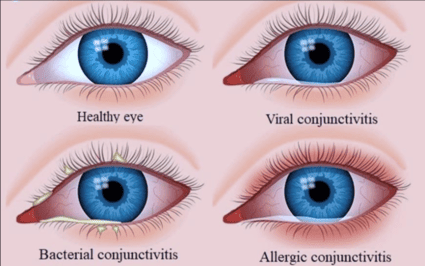

Conjunctivitis is medically defined as the inflammation of the conjunctiva. It is commonly known as "pink eye" or "red eye" due to the characteristic redness that often accompanies the condition.

- Inflammation: This refers to the body's protective response to injury or irritation, involving increased blood flow, swelling, and often pain and redness. In the case of conjunctivitis, this response is localized to the conjunctiva.

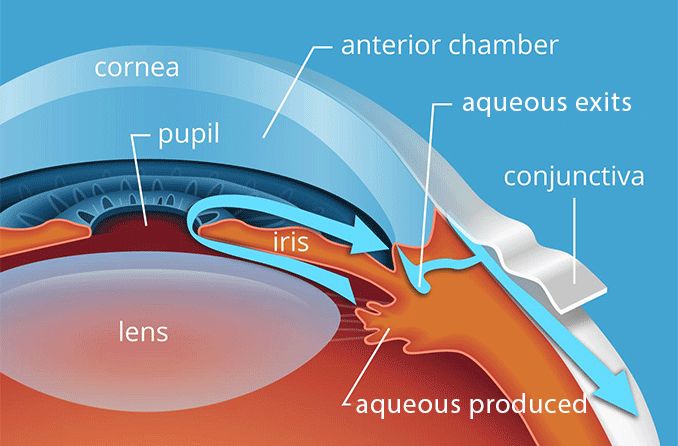

- Conjunctiva: This is the key anatomical structure involved.

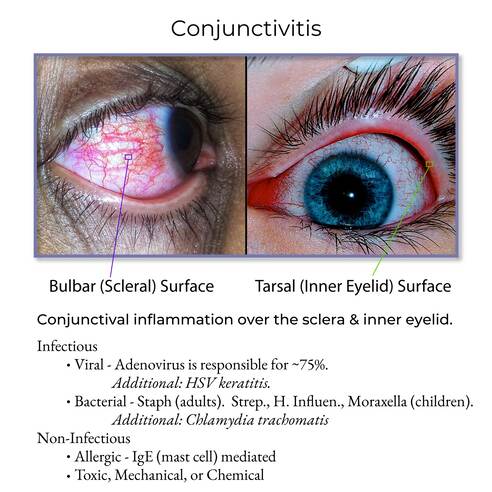

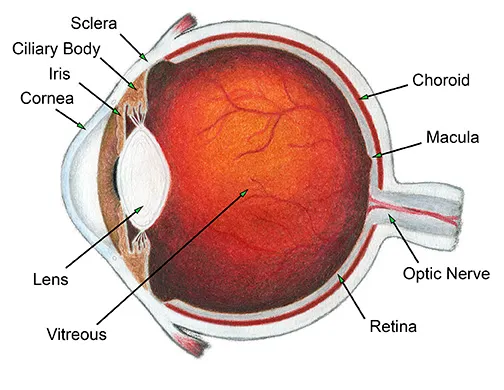

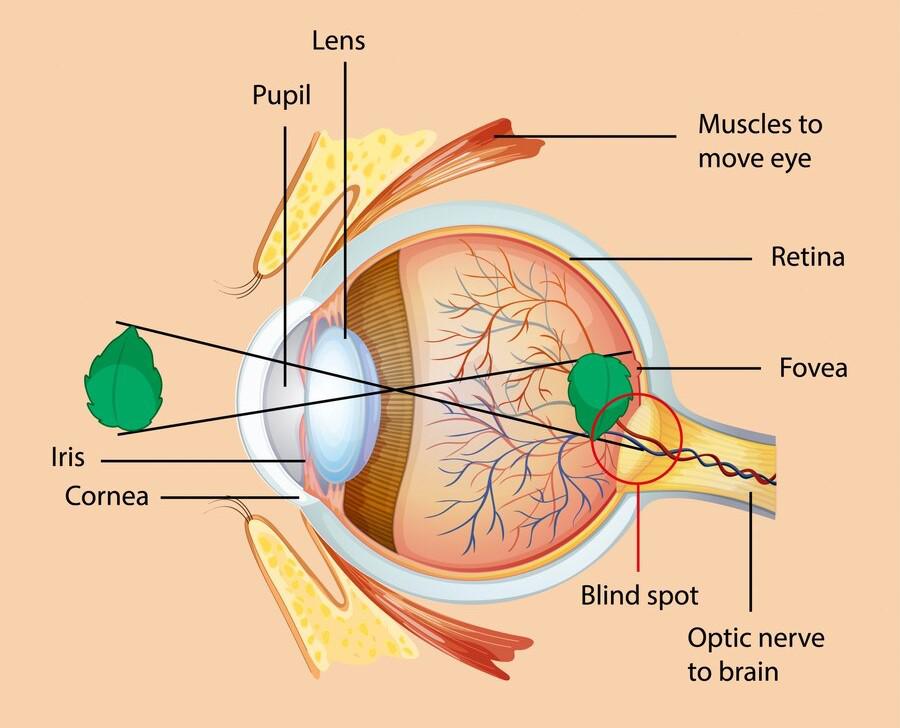

The conjunctiva is a thin, transparent mucous membrane that lines the inner surface of the eyelids (palpebral conjunctiva) and covers the anterior surface of the eyeball, extending from the limbus (the junction between the cornea and sclera) to the inner surface of the eyelids (bulbar conjunctiva).

- Palpebral (Tarsal) Conjunctiva: This portion lines the inner surface of the upper and lower eyelids. It is firmly adherent to the tarsal plates (which give the eyelids their stiffness).

- Bulbar (Ocular) Conjunctiva: This portion covers the anterior sclera (the white outer layer of the eyeball) but does not cover the cornea (the clear front part of the eye). It is loosely attached to the sclera, allowing for free movement of the eyeball.

- Fornix (Conjunctival Fornices): This is the loose fold of conjunctiva that connects the palpebral and bulbar conjunctivas. It acts as a cul-de-sac and is where the tear film collects and where topical medications can pool.

- Transparency: The conjunctiva is normally transparent, allowing the white sclera underneath to be visible.

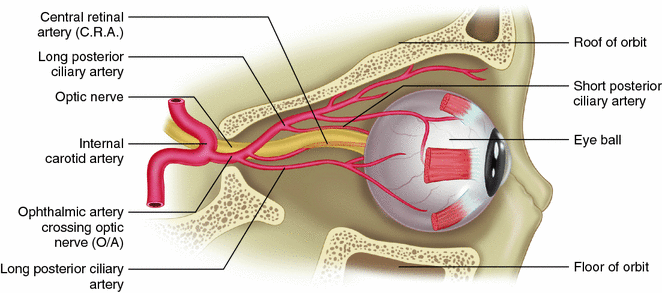

- Blood Vessels: It is richly supplied with small blood vessels. When these vessels become dilated due to inflammation, they give the eye its characteristic red or pink appearance.

- Mucous-Secreting Goblet Cells: These cells are scattered throughout the conjunctiva and produce mucin, a component of the tear film. Mucin helps to spread tears evenly over the ocular surface, moisten the eye, and trap foreign particles.

- Accessory Lacrimal Glands (Glands of Krause and Wolfring): These small glands, located in the conjunctival fornices, contribute to the aqueous layer of the tear film.

- Lymphoid Tissue: The conjunctiva contains lymphoid follicles (especially in the fornices), which are part of the ocular immune system and play a role in defending against pathogens.

- Protection: The conjunctiva helps protect the eyeball from foreign bodies and pathogens, and its smooth, moist surface facilitates easy movement of the eyelids over the globe.

The conjunctiva's exposed location and rich vascularity make it particularly vulnerable to various insults:

- Direct Exposure: It is directly exposed to the external environment, making it susceptible to pathogens (bacteria, viruses), allergens (pollen, dust), and irritants (smoke, chemicals).

- Vascularity: Its extensive blood supply means that inflammatory responses (vasodilation, increased permeability) quickly become evident as redness and swelling.

- Immune Response: Its lymphoid tissue readily mounts an immune response, leading to the characteristic cellular infiltrates and exudates seen in different types of conjunctivitis.

This category involves conjunctivitis caused by bacteria. It is typically contagious.

- Common (non-gonococcal, non-chlamydial): Caused by bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus (most common), Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis.

- Streptococcus pyogenes (haemolyticus) is virulent and usually produces pseudomembranous conjunctivitis.

- Pseudomonas pyocyanea is a virulent organism, which readily invades the cornea.

- Corynebacterium diphtheriae causes acute membranous conjunctivitis.

- Hyperacute (Gonococcal): Caused by Neisseria gonorrhoeae. A severe, rapidly progressive form that can lead to corneal perforation and vision loss if not treated urgently. Often seen in neonates (ophthalmia neonatorum) or sexually active adults.

- Neisseria meningitidis: May produce muco-purulent conjunctivitis.

- Chlamydial (Inclusion) Conjunctivitis: Caused by Chlamydia trachomatis. Can be acquired by neonates during passage through the birth canal or in adults through sexual contact. Can become chronic if untreated.

- Trachoma: A chronic form of chlamydial conjunctivitis (serovars A, B, C) that is a leading cause of preventable blindness worldwide.

- Flies (vector transmission)

- Poor hygienic conditions and poor sanitation

- Hot dry climate

- Dirty habits

- Exogenous infections: Spread directly through close contact, vector transmission (e.g., flies), or material transfer (e.g., infected fingers of health workers, common towels, handkerchiefs, tonometers).

- Local spread: From neighbouring structures such as infected lacrimal sac, lids, and nasopharynx.

- Endogenous infections: Very rare spread through blood (e.g., gonococcal and meningococcal infections).

Pathological changes of bacterial conjunctivitis consist of:

- Vascular response: Characterized by congestion and increased permeability of the conjunctival vessels associated with proliferation of capillaries.

- Cellular response: Exudation of polymorphonuclear cells (Neutrophils) and other inflammatory cells into the substantia propria of conjunctiva as well as in the conjunctival sac.

- Conjunctival tissue response: Conjunctiva becomes edematous. Superficial epithelial cells degenerate, become loose and even desquamate. Proliferation of basal layers of conjunctival epithelium and increase in the number of mucin-secreting goblet cells.

- Papillae Formation: Hypertrophy of the conjunctival epithelium with a central vascular core, often seen in bacterial conjunctivitis, especially on the tarsal conjunctiva. These appear as small, elevated bumps.

- Conjunctival discharge: Consists of tears, mucus, inflammatory cells, desquamated epithelial cells, fibrin and bacteria. If the inflammation is very severe, diapedesis of red blood cells may occur and discharge may become blood stained.

- Gonococcal Specifics: Rapid and aggressive bacterial proliferation, profound neutrophilic response, massive purulent discharge, and a high risk of corneal ulceration due to bacterial enzymes.

- Onset: Can be sudden, often starts unilaterally but can spread to the other eye. (Mucopurulent usually bilateral, although one eye may become affected 1–2 days before the other).

- Discharge: Copious, thick, purulent (pus-like) or mucopurulent discharge (white, yellow, or green). Eyelids often "stuck together" upon waking.

- Itching: Mild.

- Appearance:

- Typically there is conjunctival infection (hyperemia), especially in the fornices where the blood supply is rich.

- Eyelids may be red and inflamed.

- Flakes of mucopus seen in the fornices, canthi and lid margins is a critical sign.

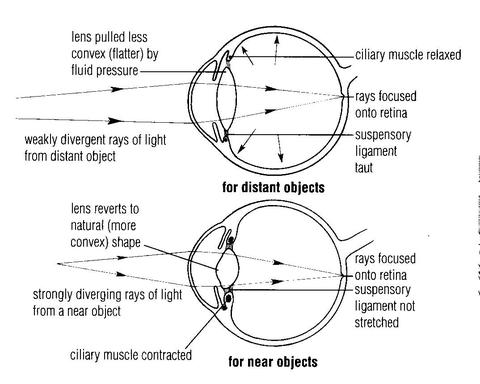

- Sensation: The patient may complain of a gritty or foreign body sensation, some discomfort, and very occasionally very mild photophobia. Vision is always unaffected (unless corneal involvement), though there may be slight blurring due to mucous flakes.

- Specific Types:

- Acute Bacterial Conjunctivitis: Marked conjunctival hyperemia and mucopurulent discharge.

- Hyperacute (Gonococcal): Extremely copious, thick, green-yellow purulent discharge, severe chemosis, painful, rapid progression.

- Chronic Bacterial (Chronic Catarrhal): Characterized by mild catarrhal inflammation.

- Infectious Period: The time during which the eye discharge is present.

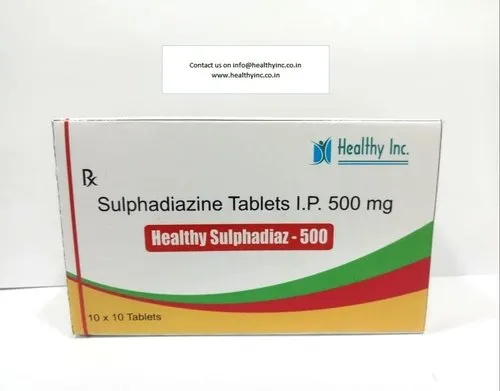

- Topical Antibiotics: Treatment may be started with chloramphenicol (1%), gentamicin (0.3%), tobramycin (0.3%), or framycetin (0.3%).

- Regimen: Eye drops 3–4 hourly in day and ointment used at night (provides antibiotic cover and reduces morning stickiness).

- Severe Cases: Quinolone antibiotic drops such as ciprofloxacin (0.3%), ofloxacin (0.3%), gatifloxacin (0.3%) or moxifloxacin (0.5%) may be used.

- Note: Bacterial conjunctivitis usually resolves without treatment; antibiotics may be needed only if no improvement after 3 days.

- Systemic Antibiotics: Required for severe cases (e.g., gonococcal, chlamydial) or in neonates.

- Clean the eyes: Remove crusts and discharge before applying medication.

- Apply Topical Antibiotics: Emphasize compliance with the full course.

- Dark Goggles: Use to prevent photophobia.

- NO Bandage: No bandage should be applied in patients with mucopurulent conjunctivitis. Exposure to air keeps the temperature of conjunctival cul-de-sac low which inhibits bacterial growth.

- NO Steroids: No steroids should be applied, otherwise infection will flare up and bacterial corneal ulcer may develop.

- Infection Control: Rigorous hand hygiene, do not share towels/pillows, wash linens in hot water. Exclude from school/work until 24 hours after antibiotics started.

This category is highly contagious and often associated with systemic viral infections.

- Adenovirus: Most common cause.

- Pharyngoconjunctival Fever (PCF): Types 3, 4, 7. Characterized by fever, pharyngitis (sore throat), and conjunctivitis.

- Epidemic Keratoconjunctivitis (EKC): Types 8, 19, 37, 54. More severe, can involve the cornea, and is highly contagious.

- Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV): Less common, but can lead to corneal involvement and vision loss.

- Acute Hemorrhagic Conjunctivitis (AHC): Caused by Enterovirus 70 or Coxsackievirus A24. Characterized by sudden onset, pain, and subconjunctival hemorrhage.

- Other causes: Varicella-zoster, Poxvirus, Mycovirus, Paramyxovirus.

- Entry: Virus replicates in conjunctival epithelial cells.

- Immune Response: Primarily a lymphocytic response. Lymphocytes and plasma cells infiltrate the conjunctiva.

- Tissue Response:

- Follicle Formation: Small, avascular mounds of lymphoid tissue (aggregates of lymphocytes), typically seen in the inferior fornix.

- Pseudomembranes: Can occur in severe cases.

- Corneal Involvement: The virus can infect corneal epithelial cells leading to epithelial keratitis (punctate lesions) and subepithelial infiltrates.

- Onset: Often sudden, typically unilateral initially but frequently spreads to the other eye within days.

- Discharge: Watery, serous, or scant mucoid discharge. Not thick or purulent.

- Itching: Mild.

- Signs: Red/pink eye, Chemosis (if severe), Follicles on palpebral conjunctiva. Bleeding from conjunctival vessels in severe adenoviral cases.

- Associated Symptoms:

- Recent Upper Respiratory Tract Infection (URTI).

- Preauricular Lymphadenopathy: Swelling/tenderness of the lymph node in front of the ear (Key diagnostic sign).

- Supportive Treatment: This is the only treatment required for adenovirus.

- Cold compresses.

- Dark glasses for photophobia.

- Artificial lubricants for comfort.

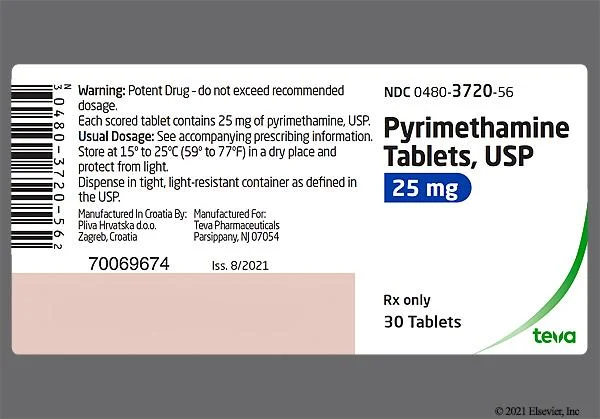

- Antivirals: NOT beneficial for adenoviral conjunctivitis. Used ONLY for HSV (e.g., topical ganciclovir/trifluridine or oral acyclovir) to prevent corneal scarring.

- Antibiotics: Topical antibiotics help only to prevent superadded bacterial infections.

- Steroids: Topical steroids should not be used during active inflammation as they may enhance viral replication and extend infectivity. (Exception: Weak steroids for severe subepithelial infiltrates or membrane formation).

- Strict Isolation/Hygiene: Highly contagious. Rigorous hand washing. Advise patients not to share towels or pillows.

- School/Work Exclusion: Generally 5-7 days depending on severity.

- Comfort Measures: Cool compresses to reduce swelling.

Non-infectious, generally not contagious.

Etiology: An immune-mediated hypersensitivity reaction (Type I) to airborne allergens.

- Simple Allergic Conjunctivitis:

- Seasonal Allergic Conjunctivitis (SAC): Triggered by seasonal allergens (tree/grass pollen). Associated with allergic rhinitis.

- Perennial Allergic Conjunctivitis (PAC): Triggered by year-round allergens (dust mites, pet dander). Onset is subacute/chronic.

- Vernal Keratoconjunctivitis (VKC): Severe, chronic, often in children/young adults, associated with atopy (asthma/eczema). Can involve the cornea (shield ulcers).

- Atopic Keratoconjunctivitis (AKC): Similar to VKC but in adults with atopy. Potentially vision-threatening.

- Giant Papillary Conjunctivitis (GPC): Associated with contact lens wear or ocular prosthetics due to chronic mechanical irritation and protein deposits.

- Mechanism: Type I (IgE-mediated) immediate hypersensitivity reaction.

- Process: Allergen binds to IgE on Mast Cells → Degranulation → Release of mediators (Histamine, prostaglandins, etc.).

- Effects:

- Histamine: Causes intense itching, vasodilation, and increased permeability.

- Cellular Infiltration: Eosinophils are predominant (abundant in discharge).

- Papillae: Large/Giant papillae form in chronic cases (cobblestone appearance in VKC/GPC).

- Symptom: Intense itching (hallmark), burning sensation, watery mucus, mild photophobia.

- Signs: Hyperemia, Chemosis (swollen juicy appearance of conjunctiva), Edema of lids.

- Discharge: Watery, clear, or stringy/ropy mucoid.

- Onset: Acute (SAC/PAC) or chronic. usually bilateral.

- Associated: Allergic shiners (dark circles), rhinitis symptoms.

- Elimination: Avoidance of allergens.

- Topical Agents:

- Vasoconstrictors: Naphazoline, antizoline (immediate decongestion).

- Antihistamines/Mast Cell Stabilizers: Olopatadine, azelastine, sodium cromoglycate (effective for prevention).

- NSAIDs: Ketorolac.

- Steroids: Only if severe (risk of side effects).

- Systemic: Oral antihistamines.

- Cool Compresses: Reduce itching and swelling.

- Cool Water: Poured over face with head inclined downward constricts capillaries.

- Artificial Tears: Wash away allergens.

- Contact Lens Management: Discontinue during flare-ups.

- Etiology: Direct exposure to chemicals (smoke, chlorine, acid/alkali) or foreign bodies.

- Pathophysiology: Direct damage to epithelial cells. Alkalis cause liquefactive necrosis (penetrate deep); Acids cause coagulative necrosis.

- Symptoms: Immediate onset, burning/stinging, watery discharge. No itching, no lymphadenopathy.

- Immediate Irrigation: Copious irrigation with sterile saline or water for 15-30 minutes is the most critical first step.

- Remove Irritant: Carefully remove foreign body.

- Artificial Tears: Lubricate and flush.

| Feature | Viral | Bacterial | Allergic | Irritant/Chemical |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discharge | Watery, serous, scant mucoid | Copious, thick, purulent/mucopurulent | Watery, clear, stringy/ropy mucoid | Watery, minimal |

| Itching | Mild | Mild | Intense | Absent (burning/stinging) |

| Lymphadenopathy | Preauricular (common) | Absent (except Chlamydia) | Absent | Absent |

| Onset | Sudden, often unilateral spreading | Sudden, unilateral spreading | Acute/chronic, usually bilateral | Immediate, history of exposure |

| Eyelids "stuck" | Mild | Prominent (especially in morning) | Mild | Absent |

| Associated Sx | URTI, sore throat, fever | None (except STI for specific types) | Rhinitis, asthma, eczema (atopy) | History of exposure (smoke, chemicals, FB) |

| Key Ocular Signs | Follicles, punctate keratitis | Papillae, (hyperacute: rapid progression) | Chemosis, giant papillae (VKC/AKC/GPC) | Redness proportional to exposure/severity |

| Contagious | Highly | Yes | No | No |

Diagnosing conjunctivitis primarily relies on a thorough history and physical examination. However, in certain cases, laboratory tests may be necessary to confirm the etiology, especially for severe, recurrent, or atypical presentations.

A detailed patient history provides crucial clues:

- Discharge: Watery, purulent, mucopurulent, ropy.

- Itching: Absent, mild, severe.

- Pain/Grittiness/Foreign Body Sensation: Severity.

- Photophobia: Presence and severity.

- Upper Respiratory Tract Infection (URTI) symptoms: Cold, cough, sore throat, fever (suggests viral).

- Allergic symptoms: Sneezing, runny nose, asthma, eczema (suggests allergic).

- Genitourinary symptoms: Urethritis, cervicitis (suggests chlamydial or gonococcal).

- Recent Illness/Exposure: Contact with sick individuals.

- Allergens: Pollen, dust, pet dander.

- Irritants/Chemicals: Smoke, chlorine, workplace chemicals.

- Contact Lens Wear: Type, duration, hygiene, solutions.

- Atopy: History of allergies, asthma, eczema.

- Immunocompromised state.

- Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs).

- Previous episodes of conjunctivitis.

- Eye drops used.

- Anticoagulants (can increase bleeding risk).

- Eyelids: Edema, erythema, crusting.

- Periorbital area: Allergic shiners, skin changes.

- Preauricular Lymph Node Palpation: Tenderness and enlargement are highly suggestive of viral conjunctivitis (especially adenoviral) or chlamydial conjunctivitis.

- Conjunctival Injection: Diffuse redness.

- Discharge Character: As described in Objective 5.

- Conjunctival Reaction:

- Follicles: Small, round, avascular lymphatic aggregates, typically on the inferior palpebral conjunctiva (classic for viral, chlamydial, toxic conjunctivitis).

- Papillae: Small, raised mounds with a central vascular core, typically on the superior palpebral conjunctiva (classic for bacterial, allergic conjunctivitis; giant papillae in VKC, AKC, GPC).

- Chemosis: Swelling of the conjunctiva.

- Pseudomembranes/True Membranes: Can be peeled off in severe viral or bacterial cases.

- Cornea: Check for epithelial defects, infiltrates, ulcers (using fluorescein staining).

- Anterior Chamber: Look for cells/flare (indicating uveitis, which can mimic conjunctivitis but is more serious).

- Iris/Pupil: Check for abnormalities.

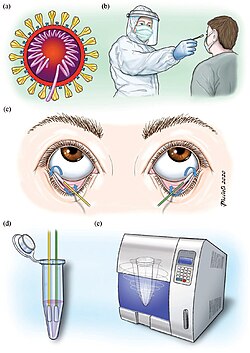

Laboratory tests are not always necessary for routine conjunctivitis, as many cases are mild and resolve spontaneously or with empirical treatment. However, they are crucial for:

- Severe, persistent, or recurrent cases.

- Cases unresponsive to initial therapy.

- Hyperacute conjunctivitis (suspected gonococcal).

- Neonatal conjunctivitis.

- Suspected chlamydial conjunctivitis.

- Corneal involvement (ulceration, severe keratitis).

- Immunocompromised patients.

- Gram Stain: Rapid identification of bacteria (gram-positive cocci, gram-negative rods, etc.) and presence of inflammatory cells (neutrophils in bacterial, lymphocytes in viral/chlamydial, eosinophils in allergic). Crucial for suspected gonococcal conjunctivitis.

- Bacterial Culture and Sensitivity: Identifies the specific bacterial pathogen and its antibiotic susceptibility. Essential for severe bacterial cases, non-responsive cases, and hyperacute forms.

- Chlamydia Testing:

- Direct Fluorescent Antibody (DFA): Detects C. trachomatis antigens.

- PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction): Highly sensitive and specific for detecting chlamydial DNA.

- Giemsa Stain: Can reveal intracytoplasmic inclusions in epithelial cells (pathognomonic for chlamydia).

- Viral Culture/PCR: Detects specific viral pathogens (e.g., adenovirus, HSV). Typically reserved for severe, recurrent, or atypical viral cases, or when HSV is suspected.

- Cytology: Microscopic examination of stained conjunctival scrapings.

- Neutrophils: Predominant in bacterial conjunctivitis.

- Lymphocytes/Monocytes: Predominant in viral conjunctivitis.

- Basophilic cytoplasmic inclusion bodies: Classic for chlamydia.

- Eosinophils/Mast Cells: Predominant in allergic conjunctivitis.

- Skin Prick Test or Blood Test (RAST/ImmunoCAP): To identify specific environmental allergens, especially in chronic or severe allergic conjunctivitis.

- Fluorescein Staining: To detect corneal abrasions, epithelial defects, or ulcers.

- Schirmer Test: May be used if dry eye is suspected as a contributing factor.

- Acute Pain related to inflammation of the conjunctiva, as evidenced by patient reports of burning, grittiness, foreign body sensation, and grimacing.

- Rationale: The inflammatory process (vasodilation, edema, cellular infiltration) directly causes discomfort and pain, which is a primary concern for patients.

- Disrupted Sensory Perception (Visual) related to ocular discharge, eyelid edema, and photophobia, as evidenced by patient reports of blurred vision, difficulty reading, and avoidance of bright lights.

- Rationale: Swelling and exudate can temporarily obscure vision, while inflammation can increase light sensitivity, impacting the patient's ability to perceive their environment clearly.

- Risk for Infection Transmission related to contagious nature of viral/bacterial conjunctivitis and lack of knowledge regarding proper hygiene, as evidenced by patient's expression of concern about spreading it to family members or observed ineffective hand hygiene.

- Rationale: Viral and bacterial conjunctivitis are highly contagious. Patients and their families need clear guidance on preventing spread. This diagnosis is not applicable to allergic or irritant conjunctivitis.

- Inadequate health Knowledge related to disease process, treatment regimen, and prevention of transmission, as evidenced by patient questions about the cause of symptoms, how to use eye drops, or concern about infecting others.

- Rationale: Patients often lack comprehensive understanding of their condition, its management, and infection control, which can lead to non-adherence and continued spread or discomfort.

- Impaired Comfort related to ocular irritation, discharge, and eyelid crusting, as evidenced by patient reports of "sticky eyes," constant need to wipe eyes, and desire for relief.

- Rationale: The physical manifestations of conjunctivitis directly interfere with the patient's comfort and can be quite distressing.

- Excessive Anxiety related to changes in vision, fear of permanent eye damage, or concern about social activities/work, as evidenced by patient expressing worries about their condition and asking repeated questions.

- Rationale: Any eye condition can cause significant anxiety, particularly if vision is affected or if the condition is perceived as unsightly or highly contagious, impacting daily life.

- Ineffective Health Maintenance related to insufficient knowledge about managing chronic allergic conjunctivitis or contact lens hygiene, as evidenced by recurrent episodes of allergic conjunctivitis or contact lens-related infections.

- Rationale: For patients with chronic forms (like allergic) or those with modifiable risk factors (like contact lens use), ongoing education and support are needed to prevent recurrence.

- Risk for Impaired Skin Integrity related to frequent wiping of periorbital area and irritation from discharge.

- Rationale: Constant rubbing or wiping to remove discharge can irritate the delicate skin around the eyes, leading to redness, dryness, or even breakdown.

- Continuously monitor visual acuity, comfort level, type and amount of discharge, eyelid swelling, and conjunctival redness.

- Assess effectiveness of prescribed treatments and document any adverse reactions.

- Monitor for signs of worsening infection or corneal involvement (increased pain, photophobia, decreased vision).

- Warm or Cool Compresses: Apply warm compresses for bacterial conjunctivitis to help loosen crusts and reduce discomfort. Use cool compresses for allergic or viral conjunctivitis to reduce itching and swelling.

- Lid Hygiene: Gently clean eyelids with a clean, warm, moist cloth to remove discharge and crusting. Always use a fresh cloth for each eye or discard after single use.

- Artificial Tears: Encourage the use of preservative-free artificial tears to soothe irritation and wash away irritants/allergens.

- Dark Glasses: Advise wearing sunglasses to reduce photophobia.

- Medication Administration: Provide clear, step-by-step instructions on how to correctly instill eye drops or apply ointment. Emphasize hand hygiene before and after, avoiding touching the eye with the dropper tip, and proper spacing of different drops.

- Expected Course: Explain the typical duration and expected resolution of symptoms.

- When to Seek Further Medical Attention: Educate on warning signs of complications (e.g., sudden vision changes, severe pain, inability to open eye, increasing redness after treatment).

- Avoid Eye Rubbing: Explain that rubbing can worsen irritation and spread infection.

- Topical Antibiotics: Administer antibiotic eye drops (e.g., erythromycin, azithromycin, fluoroquinolones) or ointment as prescribed. Emphasize compliance with the full course, even if symptoms improve.

- Systemic Antibiotics: For severe cases (e.g., gonococcal, chlamydial) or in neonates, systemic antibiotics will be prescribed and administered.

- Antivirals: If HSV conjunctivitis is diagnosed or strongly suspected, administer topical (e.g., ganciclovir, trifluridine) or oral (e.g., acyclovir, valacyclovir) antiviral medications as prescribed. This is critical to prevent corneal scarring.

- No specific antiviral for adenovirus: Treatment is generally supportive.

- Rigorous Hand Hygiene: Teach and reinforce frequent and thorough hand washing with soap and water for at least 20 seconds, especially after touching the eyes, before and after medication administration, and after contact with other people. Alcohol-based hand sanitizers can be used if soap and water are unavailable.

- Avoid Sharing: Emphasize not sharing towels, pillows, makeup, eye drops, or any personal items.

- Disinfection: Advise disinfecting frequently touched surfaces (doorknobs, phones, remote controls).

- Laundry: Wash pillowcases, towels, and clothes in hot water and detergent.

- School/Work Exclusion: Advise patients (especially children) to stay home from school/work until symptoms improve or they are no longer contagious (e.g., after 24 hours on antibiotics for bacterial, or for 5-7 days for viral depending on severity).

- Contact Lens Avoidance: Instruct contact lens wearers to discontinue lens use until the infection resolves and to discard current lenses and cases. Replace with new, sterile lenses and cases after recovery.

- Topical Antihistamines/Mast Cell Stabilizers: Administer dual-acting agents (e.g., olopatadine, azelastine) or separate antihistamine (e.g., levocabastine) and mast cell stabilizer (e.g., cromolyn sodium) eye drops.

- Topical NSAIDs: May be prescribed for mild to moderate cases (e.g., ketorolac).

- Topical Corticosteroids: For severe, refractory cases (e.g., VKC, AKC), an ophthalmologist may prescribe short courses of topical steroids (e.g., loteprednol, fluorometholone) with careful monitoring for side effects (IOP elevation, cataract formation).

- Oral Antihistamines: May be used for systemic allergic symptoms.

- Immunotherapy (Allergy Shots/Sublingual Tablets): For chronic, severe cases, referral to an allergist may be considered.

- Allergen Avoidance: Identify and advise on avoiding specific triggers (e.g., staying indoors when pollen counts are high, using air purifiers, frequent dusting, vacuuming, pet management).

- Cool Compresses: Effective for reducing itching and swelling.

- Artificial Tears: To wash away allergens and soothe the eyes.

- Contact Lens Management: Advise against contact lens wear during acute flare-ups. Consider daily disposable lenses or re-evaluate lens hygiene and type if GPC is present.

- Topical Antibiotics: May be used prophylactically if there is significant epithelial damage to prevent secondary bacterial infection.

- Topical Corticosteroids: May be used in some chemical burns under ophthalmological guidance to reduce inflammation and scarring, but their use is complex and depends on the specific chemical and severity.

- Immediate Irrigation: For chemical exposures, immediate and copious irrigation with sterile saline or water is the most critical first step. Continue for at least 15-30 minutes and seek emergency medical attention.

- Remove Irritant: If a foreign body is present, attempt to remove it carefully if superficial, or refer for removal by an ophthalmologist.

- Avoid Further Exposure: Educate on protective eyewear in occupational or recreational settings.

- Artificial Tears: To lubricate and flush out remaining irritants.

Evaluating expected outcomes allows nurses to determine if interventions were successful, if the patient's condition is improving, and if the established goals of care have been met.

- Resolution of Symptoms:

- Patient reports decreased or absence of eye redness within [specific timeframe, e.g., 3-7 days].

- Patient reports decreased or absence of foreign body sensation, burning, or grittiness within [specific timeframe].

- Patient reports improved comfort level (e.g., verbalizes less discomfort, less rubbing of eyes).

- Patient demonstrates improved visual acuity (if initially impaired).

- Effective Medication Management:

- Patient correctly demonstrates proper instillation technique for eye drops/ointment.

- Patient verbalizes understanding of the medication regimen, including dosage, frequency, duration, and potential side effects.

- Patient adheres to the prescribed treatment plan for the entire duration.

- Prevention of Complications:

- Patient's eyes show no signs of corneal involvement (e.g., no ulcers, infiltrates, or significant keratitis).

- Patient experiences no secondary bacterial infections (if the initial conjunctivitis was viral or allergic).

- Resolution of Infection:

- Patient's eyes exhibit decreased or absence of purulent/mucopurulent discharge (bacterial) or watery discharge (viral) within [specific timeframe, e.g., 24-48 hours for bacterial after starting antibiotics, 5-7 days for viral].

- Patient reports no eyelid matting upon waking.

- Preauricular lymphadenopathy (if present) is resolved or significantly reduced.

- Cultures (if taken) are negative for bacterial growth after treatment, or viral load significantly decreased.

- Prevention of Transmission:

- Patient and family members correctly verbalize and demonstrate appropriate infection control measures (e.g., hand hygiene, avoiding sharing personal items).

- Patient verbalizes understanding of the contagious nature of their condition.

- There is no evidence of spread of infection to household contacts or others.

- Symptom Control and Allergen Management:

- Patient reports significantly reduced or absence of intense itching within [specific timeframe, e.g., hours to days with effective medication].

- Patient demonstrates ability to identify and implement strategies for allergen avoidance.

- Patient experiences decreased chemosis and eyelid edema.

- Patient verbalizes a reduction in associated allergic symptoms (e.g., sneezing, nasal congestion).

- Patient with chronic allergic conjunctivitis (e.g., VKC, AKC, GPC) reports fewer flare-ups or less severe symptoms due to ongoing management.

- Resolution of Irritation and Protection:

- Patient reports cessation of burning or stinging sensation within [specific timeframe, e.g., immediately after irrigation for chemical exposure, or within hours for mild irritants].

- Patient's eyes show no residual signs of chemical injury (e.g., corneal opacification, persistent redness) or foreign body presence.

- Patient verbalizes understanding of preventative measures to avoid future exposure (e.g., wearing protective eyewear, safe handling of chemicals).

- Improved Quality of Life:

- Patient reports resumption of normal daily activities, including work, school, and social interactions, without significant discomfort or visual impairment.

- Patient verbalizes reduced anxiety related to their eye condition.

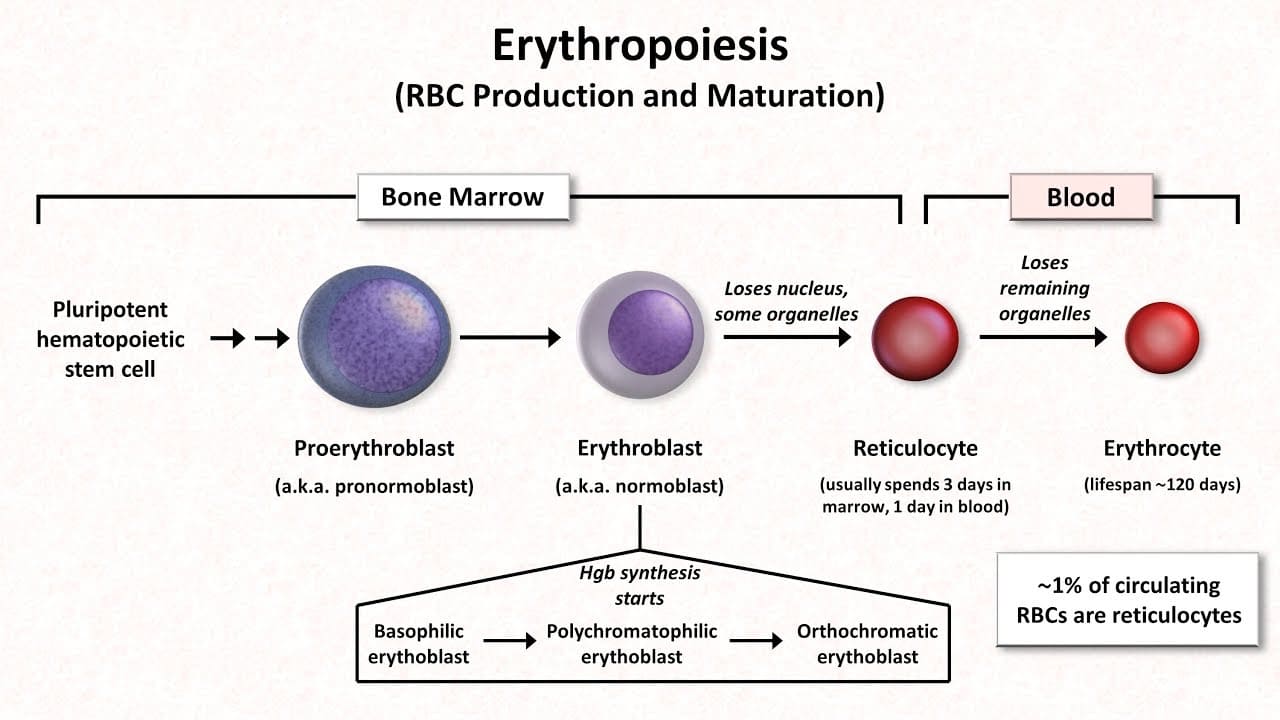

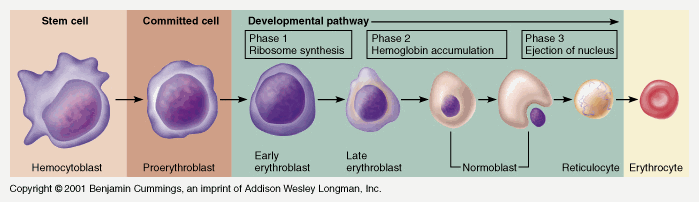

Image Placeholder - Stages in the development of blood cells diagram

Image Placeholder - Stages in the development of blood cells diagram