Your Quiz is Ready

Your Quiz is Ready Read More »

Foundations of Nursing related content

Colostomy is the surgical procedure of creating of an opening (ie. Stoma) into the colon intestine through the abdominal wall.

A colostomy is an operation that redirects the colon from its normal route, down toward the anus, to a new opening in the abdominal wall. The opening is called a stoma.

An ileostomy is a surgical procedure that brings a portion of the small intestine (the ileum) to the surface of the abdomen, creating an opening called a stoma. This opening allows stool to exit the body directly, bypassing the colon entirely.

Feature | Ileostomy | Colostomy |

Intestinal Segment | Ileum (small intestine) | Colon (large intestine) |

Stool Consistency | Liquid or semi-liquid | Can range from liquid to formed |

Frequency | Frequent (multiple times a day) | Less frequent than ileostomy |

Odor | Stronger odor | Generally less strong than ileostomy |

Control | Limited control over bowel movements | More potential for control over bowel movements |

Reasons | Ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, colon cancer, etc. | Similar reasons to ileostomy, but also for conditions specific to the colon |

It allows for drainage or evacuation of colon contents to the outside of the body.

Needs for the colostomy care:

Indications of Colostomy

By Location

By Duration:

By colostomy operation.

Characteristics of faces according to the site of colostomy:

Type | Consistency | Frequency | Odor | Skin Irritation | Pouching | Control |

Ileostomy | Liquid | Frequent (multiple times per day) | Strong | High | Continuous | Low |

Ascending Colostomy | Liquid or semi-liquid | Frequent | Strong | Moderate | Continuous | Low |

Transverse Colostomy | Mushy or semi-solid | Less frequent | Strong | Moderate | Continuous | Moderate |

Descending Colostomy | Solid | Less frequent | Moderate | Low | Needed | Moderate |

Sigmoid Colostomy | Similar to normal bowel movements | Closer to normal bowel frequency (1-2 times/day) | Similar to normal | Low | Often needed, longer wear times possible | High |

Note:

Control: Refers to the ability to control bowel movements.

Pouching: Continuous pouching means the pouch needs to be worn all the time.

Requirements

Top shelf | Bottom shelf |

– Bowl of warm water | – Disposable gloves |

– Gauze swabs | – Soap in a dish |

– Cotton balls | – New colostomy bag |

– Graduated container | – Colostomy adhesive and measuring guide |

– Large receiver | – Barrier cream |

– Towel |

Procedure

Steps | Action | Rationale |

1. | Follow the general rules. | |

2. | Turn down the bed clothes. | To expose the stoma and to avoid soiling bed clothes |

3. | Remove the soiled bag gently, taking care not to pull the skin. | To protect underlying skin from damage. |

4. | Wash the area around the stoma with soapy water and dry well. Apply a little barrier cream if necessary. | To remove excretions and old adhesive. |

5. | Re-measure the stoma and make the correct measurement. | To make sure that the bag fits correctly. |

6. | Cut the correct size of circle in the stoma adhesive, using the measuring guide and apply it on the stoma. | An opening that is too small can cause trauma to the stoma, exposed skin will be irritated by urine if opening is too large |

7. | Apply a clean bag on the stoma | To prevent infection. |

8. | Remove the soiled articles, assess patient’s response to the procedure and leave the patient comfortable. | Promotes more patient’s understanding about the colostomy and the need for more instructions. |

9. | Wash and dry hands. |

Procedure of the Colostomy care in children

1. Comfort Alteration related to abdominal incision evidenced by:

2. Impaired Skin Integrity related to the presence of stoma evidenced by:

3. Body Image Disturbance related to the presence of stoma evidenced by:

4. Knowledge Deficit related to stoma care and lack of experience evidenced by:

Assessment of the Stoma

Protecting the Skin

Clothing

Activity

Diet

Client and Family Teaching

Health Education

The patient should be able to do the following before being discharged:

Selecting the Pouch

Colostomy Irrigation

Feeding after Colostomy and Control of Smell

Assisting the Patient to Adapt Psychologically to a Changed Body and Sexual Activity

General Care

Abnormal and Danger Signs in a Stoma

Routine Observations

1. Surgical Complications:

2. Stoma-Related Complications:

3. Skin Issues:

4. Bleeding and Obstruction:

5. Fluid and Electrolyte Imbalance:

6. Psychosocial and Nutritional Issues:

Perform Colostomy Care Read More »

Gastric lavage is the process of cleaning out stomach contents.

Gastric lavage is a gastrointestinal decontamination technique that aims to empty the stomach of toxic substances by the sequential administration and aspiration of small volumes of fluid via a nasogastric tube or stomach tube.

Gastric lavage is the process of washing out of the stomach via a nasogastric tube or stomach tube.

Lavage is ordered to wash out the stomach (after ingestion of poison or an overdose of medication, for example) or to control gastrointestinal bleeding. If the patient does not have a nasogastric tube in place already, the physician will order the insertion of the appropriate tube.

Gastric lavage is a clean procedure.

Requirements

Trolley

Top Shelf | Bottom Shelf | At the Bed Side |

– Rubber tubing, stomach tube, funnel | – Mackintosh cape and towel | – Suction machine if the patient is unconscious |

– Connection and clip | – Receiver | – Hand washing facilities |

– 2 Gallipots | – Jar for stomach contents | – Screens |

– Bowl of swabs | – Lubricant | |

– Vomitus bowl | – Adhesive strapping | |

– 20 ml syringe | – Bucket for collecting stomach contents | |

– Litmus paper | – 3 receivers | |

– Jar of water |

Procedure for Gastric Lavage

Steps | Action | Rationale |

1. | Follow the general rules.

| To enable cooperativeness. To ensure privacy. To prevent unnecessary movement. |

2. | Place a bucket on the floor at the bedside. | To collect wastes. |

3. | Request the patient to sit up if conscious. If unconscious, put the patient in a prone position and place a mackintosh cape and towel around the patient’s neck and bed clothes. | To protect the bed and patient. |

4. | Connect up the funnel to the tubing using a connector but keep the stomach tube separate until it has been passed. | To prevent aspiration of the fluid by the patient. |

5. | Lubricate the tube and pass it over the tongue into the pharynx and esophagus. | To ease passage of the tube. |

6. | Keep on asking and encouraging the patient to swallow. | To gain patient’s cooperation. |

7. | Connect the syringe on the tube and withdraw some stomach content. | To ensure that the tube is in the stomach. |

8. | Test the stomach content with a litmus paper to confirm that you are in the stomach. | Acidic stomach content will turn blue litmus paper red. |

9. | Clip the stomach tube with an artery forceps and place it in the receiver. | To prevent backflow of stomach contents. |

10. | Apply a clip to the funnel and tubing then attach it to the stomach tube. | To prevent the flow of fluids before starting the procedure. |

11. | Open the clip and allow approximately 300 mls of fluid to run into the lower funnel until level begins to rise; invert the funnel into the bucket to siphon out the stomach contents. Repeat the procedure until the fluid which is returning is clear. Note the nature of the stomach contents. | To empty the stomach of unwanted or harmful contents. |

12. | Clip the stomach tube, withdraw it from the stomach evenly and quickly, disconnect the tube from the funnel and tubing and place it in the receiver. | To prevent trauma to the patient. |

13. | Give the patient a mouthwash, thank him and clear away the requirements. | To encourage patient’s comfort. |

14. | Wash your hands and document the findings. (a). Type and amount of lavage solution used. (b). Appearance, odor, color, and amount of gastric return. (c). Patient’s tolerance to procedure. (d). Disposition of specimens. Clear away all the requirements. |

Carry Out Gastric Lavage Read More »

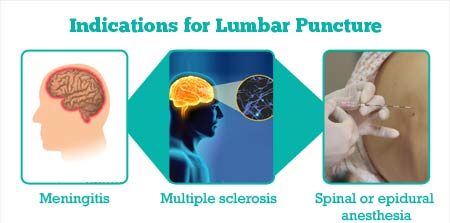

Lumbar puncture is a sterile procedure in which a spinal needle is inserted, between the third and fourth lumbar vertebrae in the lower spine at the subarachnoid space i.e. the space between the spinal cord and its covering, the meninges to obtain samples of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) for qualitative analysis.

Lumbar puncture refers to the introduction of a special needle into the subarachnoid space to withdraw cerebral spinal fluid.

The site of the puncture can be between the 3rd and 4th or 4th and 5th Lumbar vertebrae where there is no danger of damaging the spinal cord.

1. Measure cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pressure: Increased pressure within the skull, known as intracranial pressure, can be a sign of various conditions. A lumbar puncture can measure CSF pressure and assess for potential complications.

2. Assist in the diagnosis of suspected CNS infections: This includes:

3. Evaluate and diagnose demyelinating or inflammatory CNS processes: This includes:

4. Infuse medications: This includes:

5. Treat normal pressure hydrocephalus: A condition where excess CSF accumulates in the brain, leading to symptoms like walking difficulties and cognitive decline.

6. Treat cerebrospinal fistulas: Abnormal connections between the CSF space and other parts of the body.

7. Treat idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH): A condition of increased pressure within the skull with no clear cause.

8. Placement of a lumbar CSF drainage catheter: A thin tube inserted into the spinal canal to drain excess CSF.

Equipment for Lumbar Puncture

|

Top shelf |

Bottom shelf |

Bed side |

|

Sterile lumbar puncture pack containing: – 3 Gallipots – 2 Sterile drapes – Sterile towel – Cotton and gauze swabs – Receivers – Receiver containing sponge holding forceps, dissecting and artery forceps. – 2 spinal needles. – A pair of sponge holding forceps – A pair of sterile gloves. – Masks Gallipots are for; > Gallipot for antiseptic lotion > Gallipot for sterile cotton swabs > Gallipot for sterile gauze swabs. |

A tray containing: – Two 10 ml sterile syringes with needles – Two 2 ml sterile syringes with needles – Two pairs of sterile gloves – Two lumbar puncture needles – Lignocaine 2% – Antiseptic solution like Iodine, methylated spirit or alcohol. – At least 3 specimen bottles – Dressing mackintosh and towel – Adhesive tape/colloid – 2 drums of gauze dressings and swabs – Emergency tray – Spinal manometer – Laboratory request forms – Emergency tray – Cheatle forceps |

– Hand washing equipment – Screen – Safety box – Bedpan and urinal – A good source of light at the bedside |

Steps | Action | Rationale |

1. | Follow the general rules. | |

2. | Offer a bedpan to the patient. | To promote comfort. |

3. | Position the patient in any of the following positions: i. The patient may sit up on the stool and bend forward with the head between the knees ii. The patient may lie in a lateral position with the buttocks close to the edge of the bed; the knees and hip fully flexed drawn towards the chin, one pillow is placed under the head. A fracture board is provided. | A flexed position increases the space between the vertebrae. A hard surface prevents sagging in the bed and interference with the procedure. |

4. | Encourage the patient to remain in a flexed position until the procedure is completed. | Prevent risk of trauma. |

5. | Leave the patient covered and expose only the lumbar region. | To provide privacy. |

6. | Provide good light at the lumbar region. | To see the right site clearly. |

7. | Assemble the requirements for the top shelf of the trolley. | Promote easy access. |

8. | Pour antiseptic lotion into one of the gallipots and the doctor cleanses the puncture site then drapes the area. | For infection prevention and control |

9. | Wash hands, dry and put on gloves. | To maintain sterility |

10. | Assist the doctor in cleaning the lumbar region, giving local anaesthesia and in performing the lumbar puncture in between the 3rd and 4th or 4th and 5th lumbar vertebrae. | Promote success of the procedure and prevent injury to the spinal cord. |

11. | Unscrew the specimen bottles and place them about 1 cm below the needle to receive the cerebral spinal fluid. | To avoid contamination. |

12. | Reassure the patient and observe the condition, colour, pulse and respiration rate, and report any changes or complaints. | To detect complications on time. |

13. | Label the specimen, and take them to the laboratory with a laboratory request form. | For diagnosis of causative organisms. |

14. | Assist the doctor to seal the puncture site with tincture benzoin or collodion and apply the dressing. | To prevent leakage of CCF |

15. | Instruct the patient to stay confined to bed in a flat position and to be moved only if necessary for at least 12 hours. | To avoid complications like severe headache and backache. |

16 | The used equipment is cleared away. | To promote ward maintenance, |

17 | Monitor patient’s condition for ¼ , ½ 1, 2 and 4 hourly for 24 hrs depending on the patient’s condition. | To detect complications and manage appropriately. |

18 | Clear away the trolley and wash hands. | To prevent the spread of infections. |

19 | Document the procedure. | To promote follow up. |

Points To remember:

Before the Procedure

During the Procedure

After the Procedure

The lumbar puncture procedure must be performed with extreme care and aseptic technique to avoid complications such as:

Prevention of Post-Lumbar Puncture Headache

To prevent post-lumbar puncture headache, consider the following measures:

Prepare For Lumbar Puncture Read More »

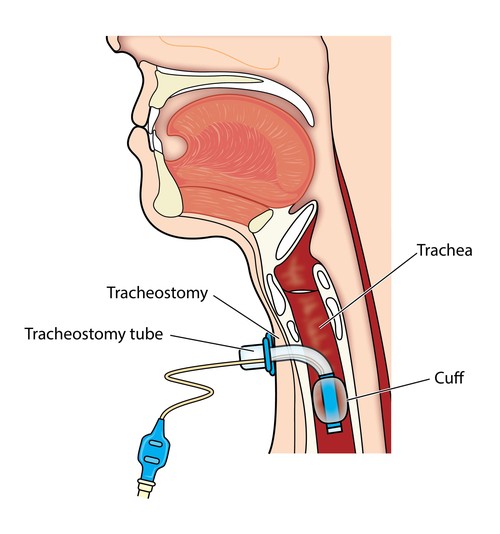

A tracheostomy is a surgical procedure usually either temporary or permanent that involves creating an opening in the neck in order to place a tube into a person’s windpipe.

The tube is inserted through a cut in the neck below the vocal cords( larynx) to allow air to enter the lungs.

Breathing is then done through the tube, bypassing the mouth, nose, and throat. A tracheostomy is commonly referred to as a stoma. This is the name for the hole in the neck that the tube passes through.

Airway Obstruction:

Ventilation & Airway Management:

Secretion Management & Aspiration Prevention:

Other Indications:

1. Prophylactic Tracheostomy:

2. Patients with Compromised Respiration:

3. Trauma and Injury:

4. Infections and Inflammatory Conditions:

5. Secretions and Obstruction:

6. Burns and Trauma:

7. Neurological Disorders:

8. Pulmonary Conditions:

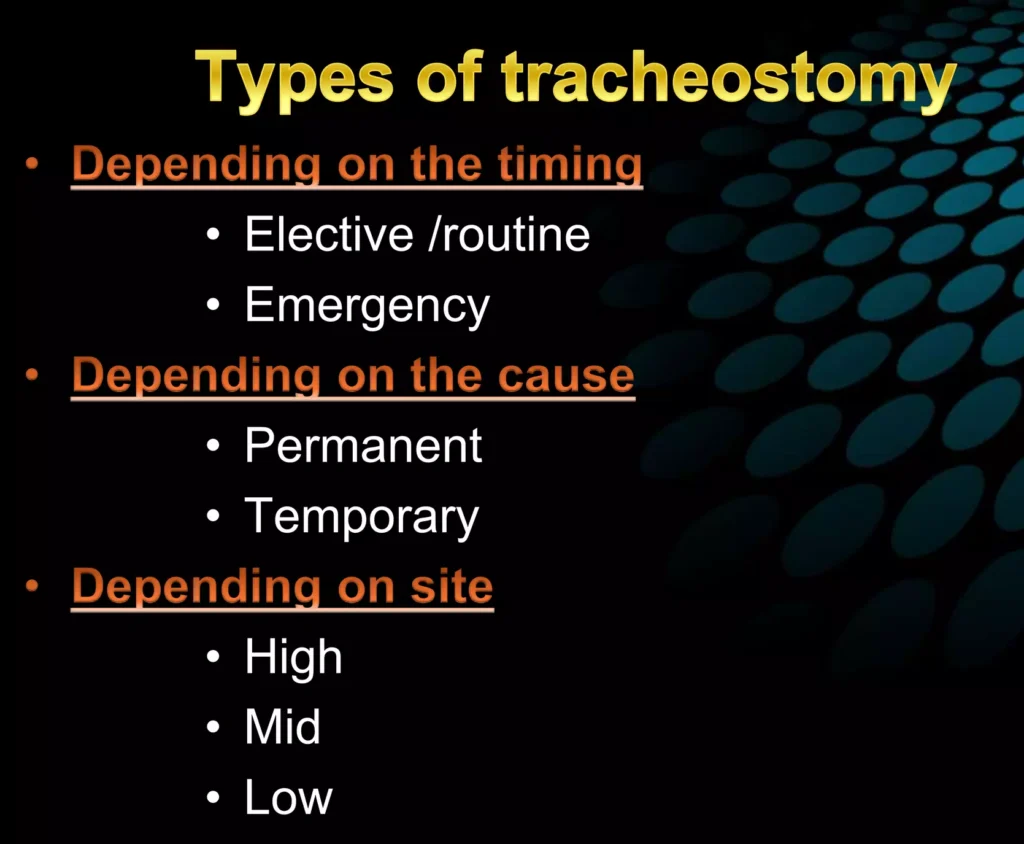

Depending on the Timing:

Depending on the Cause:

Severe spinal cord injuries

Muscular dystrophy

Cerebral palsy

Certain types of laryngeal cancer

Severe airway obstruction from birth defects

Temporary Tracheostomy: This is used for a limited duration to manage temporary issues with breathing. Examples include:

Severe airway obstruction due to infection or trauma

Facilitating mechanical ventilation during recovery from surgery

Allowing for airway clearance in patients with thick secretions

Managing post-extubation airway issues

Depending on the Site:

Tracheostomy tubes are essential for patients requiring a long-term airway management. These tubes come in various types and sizes, designed to meet individual needs and anatomical variations.

Types of Tracheostomy Tubes:

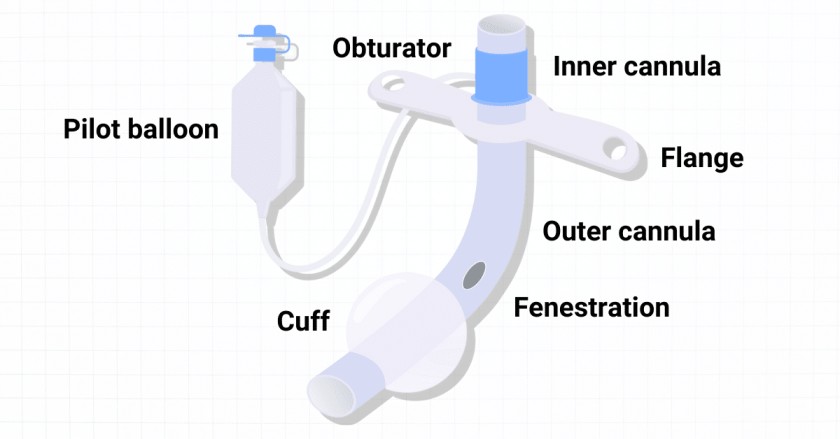

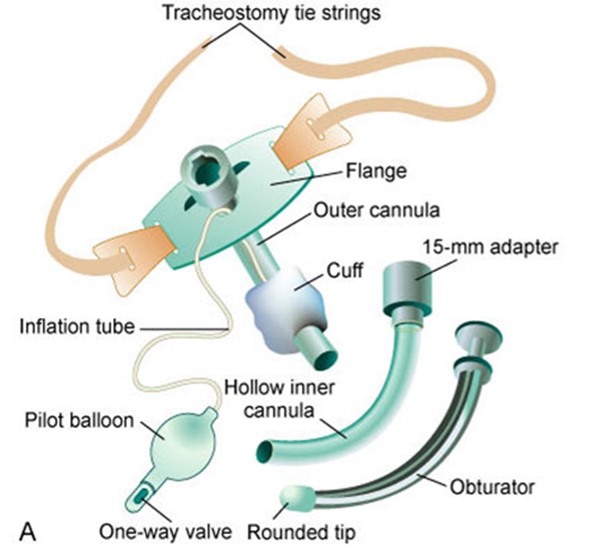

Components of a Tracheostomy Tube:

Tracheostomy tube Materials

1. Plastic: Polyvinyl chloride (PVC) and polyurethane are the most common plastics used.

Advantages:

Disadvantages:

2. Silicone:

Advantages:

Disadvantages:

3. Metal (Jackson Tubes): Sterling silver or stainless steel.

Advantages:

Disadvantages:

Purposes/Aims of Providing Tracheostomy Care:

Pre-operative care for tracheostomy

Psychological preparation of the patient and relatives is very important. They must be reassured that the artificial opening will make the breathing much easier and a simple explanation given to them about the instruments that will be seen around the bed after operation. Simple breathing exercise should be encouraged, it’s important to explain to the patient that forcible breathing is not necessary when a tracheostomy tube is in position.

General Post-operative Care:

Postoperative Management – Immediate Care: Immediate post-operative care should be conducted in an intensive care unit equipped with adequate resuscitation tools.

Continuous Post-operative Care:

Tracheostomy Tube Management:

Post-operative Ambulation:

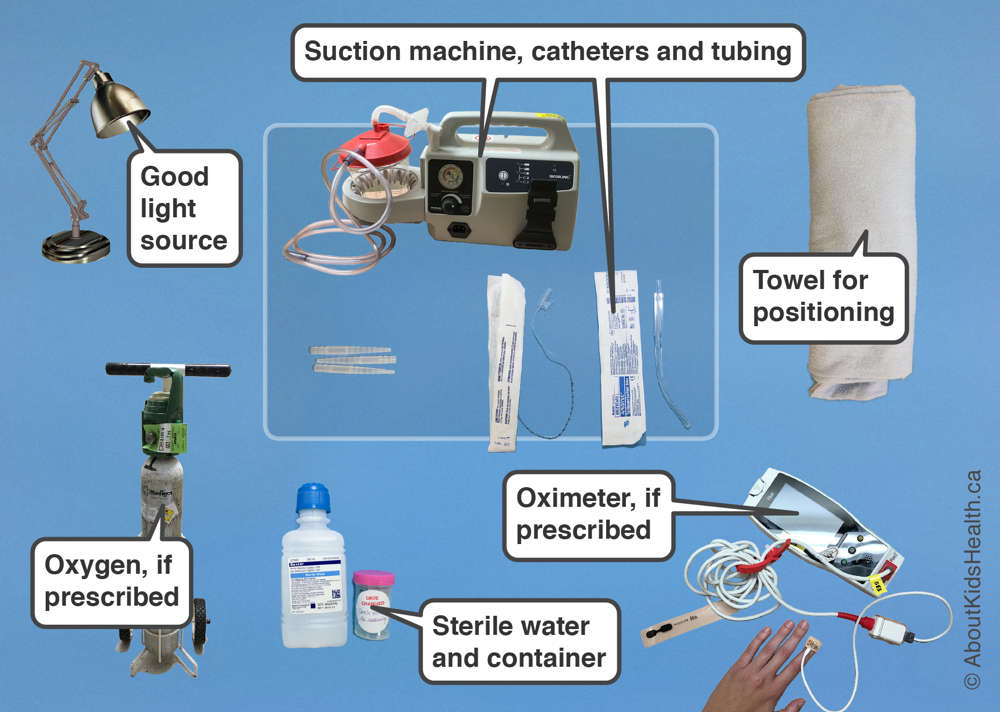

Equipment for Tracheostomy Care

Top Shelf | Bottom Shelf | Bedside |

Tracheal dilators (various sizes) | Sterile gloves | Hand washing equipment |

2 Artery forceps | Mouth care tray | Oxygen cylinder |

3 Gallipots | Bell | Screen |

2 Receivers | Pen and paper | Suction machine |

Pair of scissors | Sodium bicarbonate | Safety box |

Tray with 2 small tracheostomy tubes (one smaller than the other) | 2 ml syringe | |

Appropriate suction catheter | A bottle of Normal saline | |

Three receivers | Protective gears | |

Sterile dressing pack | Drum of sterile gauze swabs |

General rules

Tracheostomy Care Steps:

Tape and pad the tie knot: Place a folded 4-in. x 4-in. gauze square under the tie knot and apply tape over it to prevent skin irritation and confusion with gown ties.

Check the tightness of the ties: Frequently assess the tightness of the ties and position of the tracheostomy tube. Swelling of the neck can cause tightness, interfering with coughing and circulation. Loose ties can allow the tube to extrude.

Document all relevant information: Record suctioning, tracheostomy care, and dressing change, including your assessments.

Home Care Modifications:

Suctioning a Tracheostomy Tube:

Moistening and Filtering the Air

Steps | Action | Rationale |

1 | Soak a thin piece of gauze in sterile normal saline and place it across the opening of the tube. | To moisten the inhaled air and trap the dust. |

2 | Tape the gauze in position. | To secure it and prevent dislodging. |

3 | Document date and time. | To aid follow up of the patient. |

Cleaning and Dressing of Tracheostomy Tube

Steps | Action | Rationale |

1 | Suction the existing tracheostomy tube immediately before removing it out. | To prevent mucus to block the airway as the tube is removed. |

2 | Remove the inner existing tube and immerse in half strength hydrogen peroxide. | To remove dry mucus secretion and decontaminate the tube. |

3 | Insert the new tube and tie it with tapes on the outer tube in the following way: | To secure it. |

– Assistant holds the existing tube while the second nurse cuts and removes the tapes from around the patient’s neck. | ||

– Assistant removes the existing tube while the second nurse immediately inserts the new tube into the stoma and removes the introducer (if applicable). | ||

– Check the tension of the ties to allow one finger to fit comfortably between the skin and the tapes, adjust if necessary. Finish the tapes by making a reef double knot and cut off any excess fabric leaving approximately 3 cm. | ||

4 | Apply a new tracheostomy dressing under the tapes. | To absorb the drainage. |

5 | Position and observe the patient’s breathing immediately after changing the tube. | To ensure normal breathing. |

6 | Do post tracheostomy suction. |

Dressing Tracheostomy

Steps | Action | Rationale |

1 | Change the dressings carefully by loosening the soiled dressing from around the tube. | To promote infection prevention. |

2 | Clean the area with normal saline and dress with a sterile gauze swab. | |

3 | After changing the dressings, check that the tapes of the tubes have not become loose. | To secure the tubes. |

4 | Document procedure and time. | To aid follow up of the patient. |

Final Removal of the Tracheostomy Tubes

Steps | Action | Rationale |

1 | Cover the tube with a dressing for increasing periods of time (tracheotomy training) before removal of the tube to see how the patient breathes. | It is important to ensure that the patient is able to breathe normally before the tube is removed. |

2 | After removal, apply a dressing over the stoma until it closes. | To prevent infection. |

3 | Take the patient’s rate hourly for the first twelve hours. | To monitor breathing. |

Points to remember

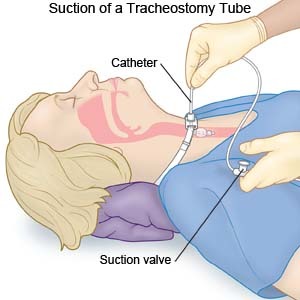

Suctioning of the tracheostomy tube is necessary to remove mucus, maintain a patent airway, and avoid tracheostomy tube blockages. The frequency of suctioning varies and is based on individual patient assessment.

Procedure

Steps | Action | Rationale |

1 | Observe the general nursing rules. | |

2 | Explain to the patient that the procedure may induce some cough. | To gain the patient’s cooperation. |

3 | Pinch the suction tube while entering the tracheostomy. | To prevent injury to surrounding tissues and pulling out the tracheostomy tube. |

4 | Insert the suction tube into tracheostomy tube down according to premeasured individual tracheostomy tube. Control the suction tube and gently suck out the mucus for 5-10 seconds. | To prevent trauma and induction of cough. |

5 | Then gently withdraw the catheter while maintaining suction until the mucus is completely removed from the tracheostomy tube. | To facilitate adequate air passage and ease breathing. |

6 | Clear away the used requirements, thank and leave the patient comfortable. | To ensure that the patient is breathing well and resting. |

7 | Document the procedure. | To promote continuity of care. |

Note:

Special safety considerations:

Perform Tracheostomy Care Read More »

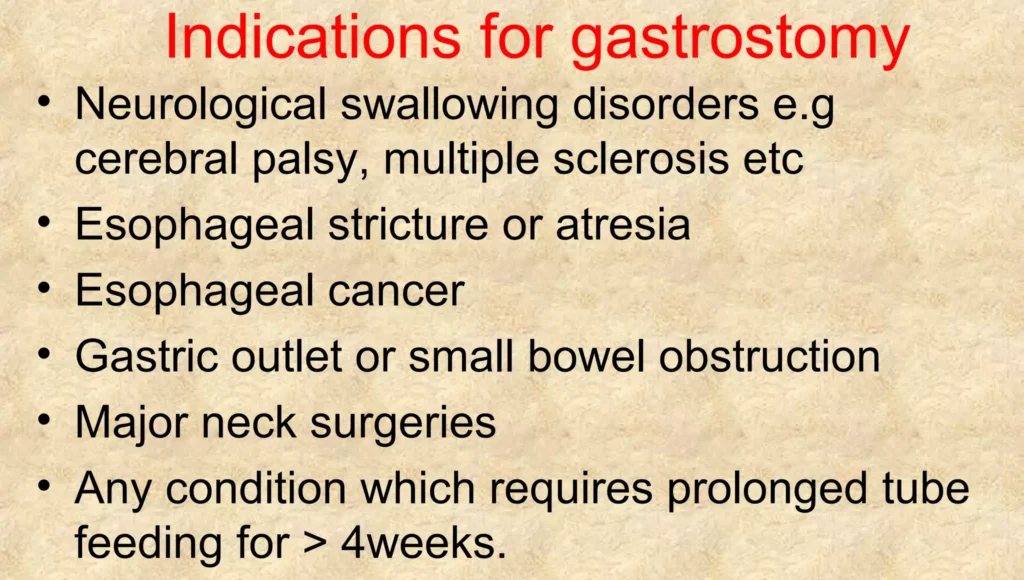

Gastronomy Feeding is feeding of a patient by means of an opening directly into the stomach through the abdominal wall.

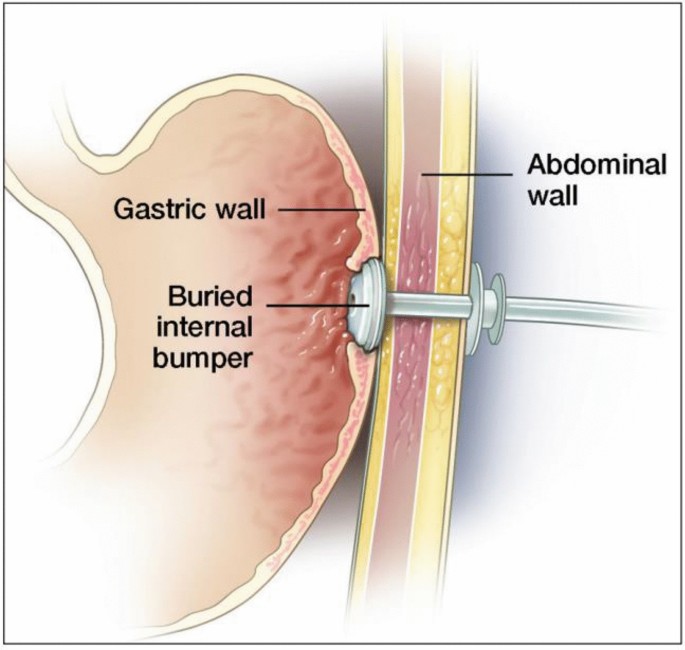

They are commonly surgically inserted endoscopically through the abdominal wall, and held in place by an internal balloon or bumper and external fixator. Gastrostomy feeding is a successful method of enteral feeding providing daily nutritional requirements in specialist liquid form directly into a patient’s stomach via a flexible tube.

Inability to Swallow Safely:

Prolonged Malnutrition:

Impaired Digestion & Absorption:

Delayed Gastric Emptying:

Coma or Altered Consciousness:

Chronic Vomiting or Reflux:

Premature Infants:

Operations of the upper gut: Procedures involving the alimentary canal, mouth, nose, and esophagus may necessitate gastrostomy feeding to allow for healing and recovery.

Feeding tubes are classified based on their length and retention mechanism:

A. Long Tubes:

B. Skin-Level Tubes:

REQUIREMENTS

A tray containing;

At the bedside:

PROCEDURE

Steps | Action | Rationale |

1. | Observe the general rules of nursing procedure. | |

2. | Expose the gastrostomy catheter. | To aid easy working. |

3. | Protect the bed linen with a mackintosh and towel. | This prevents soiling of the bed. |

4. | Wash hands and check temperature of the feed. | To prevent the spread of infection. |

5. | Aspirate and measure the stomach content before giving the feed. | To ensure feeds are absorbed. |

6. | Pinch proximal end of the gastronomy tube and connect funnel after removing the spigot. | To avoid air entry into the stomach. |

7. | Pour 10mls of water into the funnel, let it run through the tube slowly and followed by a prescribed amount of feed. Rinse the tube with 10m Is of warm boiled water. | To ensure patent tube throughout the procedure. |

8. | Pinch and disconnect the funnel when feeding is over and replace the spigot. | To prevent air entry into the stomach and backflow. |

9. | When the wound has not yet healed carry out gastrostomy toilet i.e. clean skin around the tube with normal saline and apply a protective cream e.g. Zinc Oxide and cover with dry dressing. | To promote healing and prevent infection. |

10 | Record the type, food amount given, and time. | Monitor input and output. |

11. | Provide oral hygiene, clean equipment and leave the patient comfortable. | To prevent infection to the patient. |

12. | Clear the trolley and wash hands. | To prevent cross infection. |

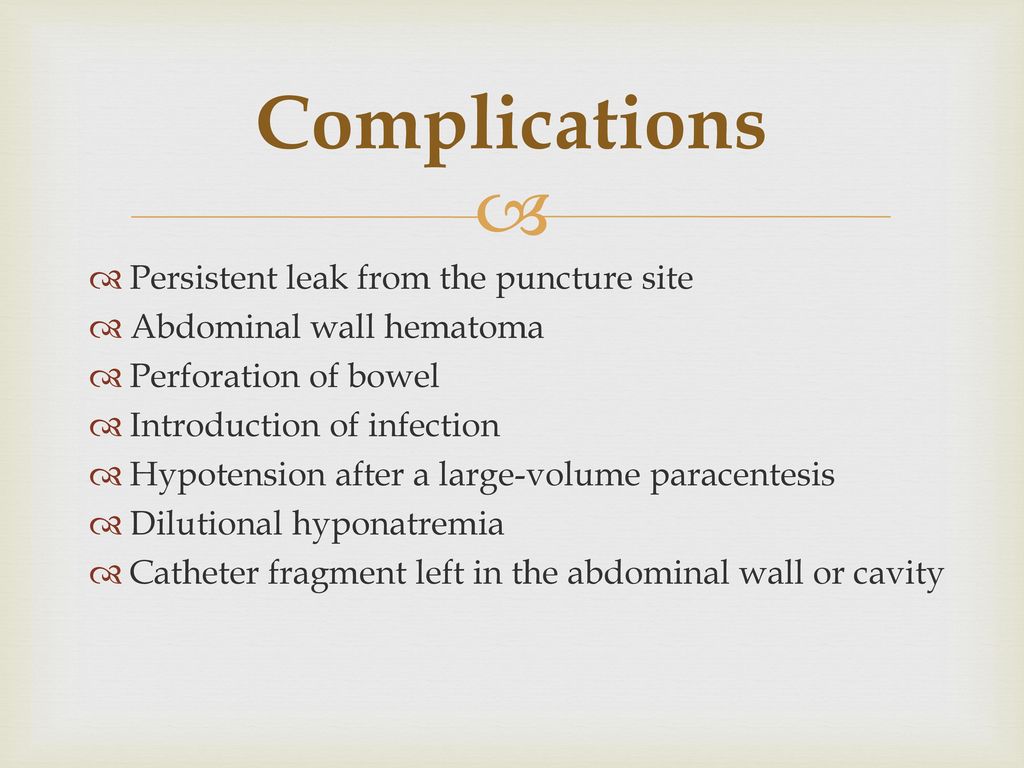

1. Tube-Related Complications:

2. Site-Related Complications:

3. Gastrointestinal Complications:

4. Systemic Complications:

5. Metabolic Complications:

Perform Gastronomy Feeding Read More »

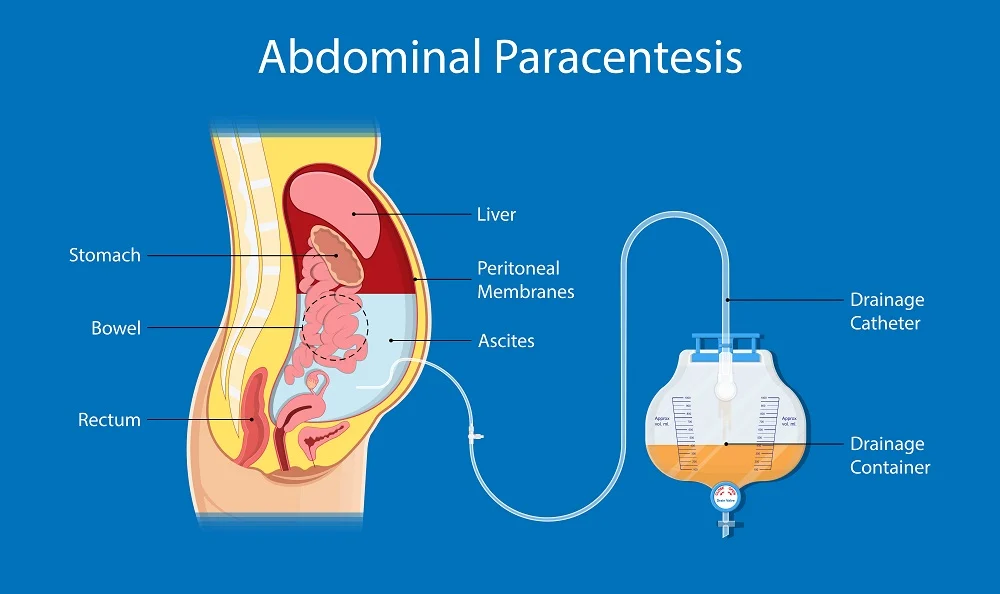

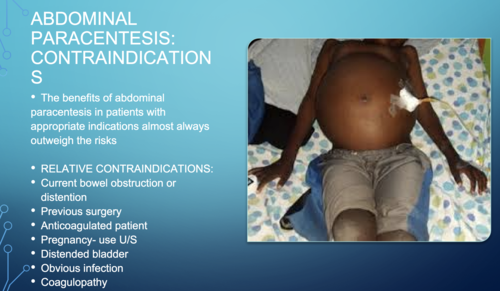

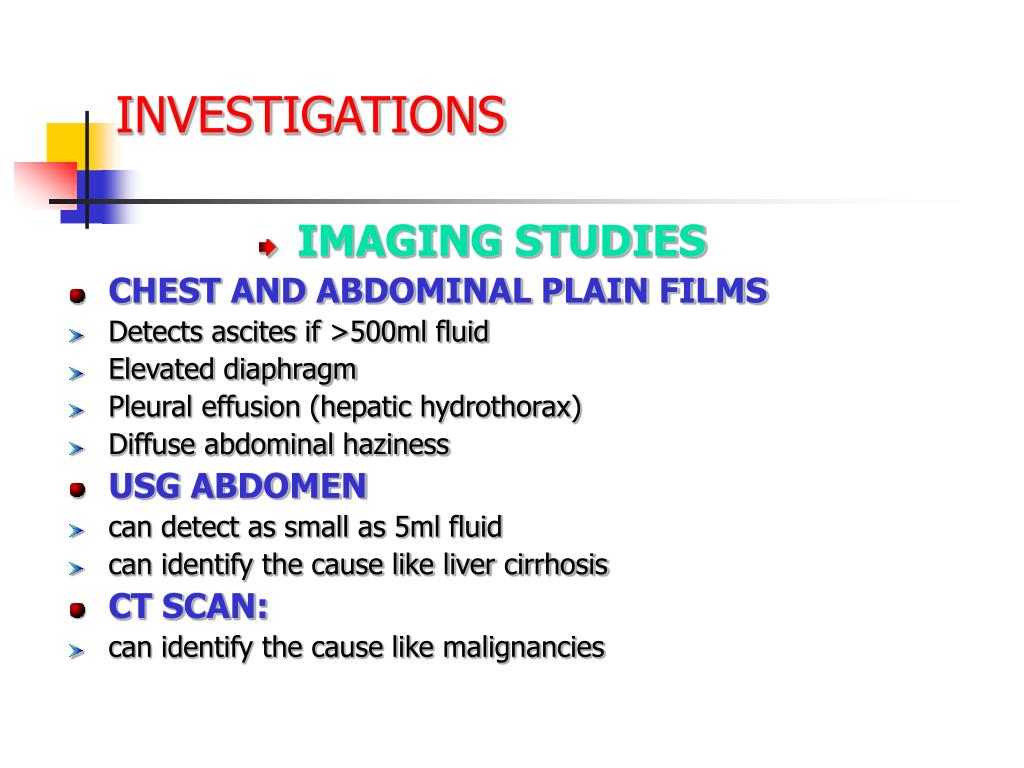

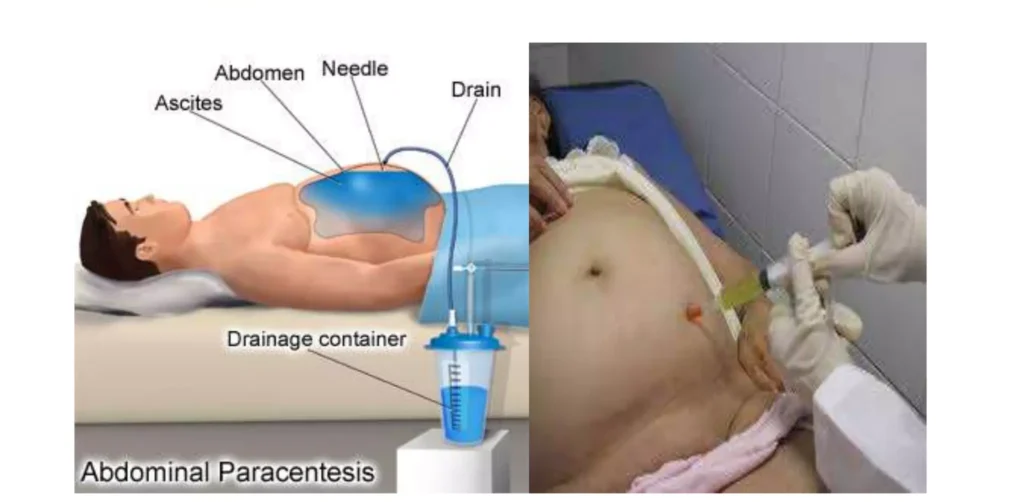

Abdominal paracentesis is a sterile surgical procedure in which a needle is inserted into the peritoneal cavity in order to drain out excess ascitic/peritoneal fluid.

This is the procedure done to aspirate fluid from the peritoneal space (ascites).

Paracentesis: it’s removal fluid from the belly. It is commonly called a ‟tap”.(Abdominal Tap)

Tapping of ascites is usually undertaken to take off small volumes of ascites for analysis. This is in comparison to paracentesis where a drain is inserted whereby larger volumes can be removed.

Specific Indications for Paracentesis:

Diagnostic Purposes: Chemical, Bacteriological, and Cellular Analysis: Paracentesis allows for the study of the composition of the peritoneal fluid. This helps to diagnose;

Therapeutic Purposes:

Paracentesis can be performed in two ways:

Prior to Paracentesis

Routine Investigations of Ascitic Fluid

Additional Investigations

Trolley

Top shelf (with sterile trays) | Bottom Shelf (tray containing) | At the bedside |

|

|

|

Procedure

Steps | Action | Rationale |

1. | Follow the general rules. | |

2. | Give a bedpan or urinal before the procedure. | To provide and avoid distractions. |

3. | Put the patient in a sitting up position well supported. | Facilitates easy drainage of the fluid. |

4. | Turn the bed clothes down to the top of the thighs. | To expose the area required for the procedure. |

5. | Roll the gown or jacket up to expose the abdominal area, if it is cold cover the chest. | To prevent soiling it and maintain sterility. |

6. | Assist doctor to give local anaesthesia and a small incision is made between the umbilicus and pubis in the left iliac fossa. The cannulae is inserted and secured in position with the strapping. | |

7. | Give specimen bottles to Doctor for collection of specimen if required. | To aid diagnosis. |

8. | Assist the doctor to connect the drainage tubing to the bottle and place it below the bed. | To aid gravity for draining. |

9. | Apply the many-tailed bandage firmly around the abdomen, and fasten it with a safety pin. | To secure the abdominal muscles that had been distended. |

10. | When the procedure is finished, clear the trolley away and wash hands. | To maintain hygiene |

11. | Inspect the many tailed bandages very frequently. Undo it and reapply it firmly as soon as it becomes loose. | To ensure continuous flow of fluids. |

12. | When the drainage is finished remove the cannulae and seal the puncture with a sterile dressing. | To prevent infection from entering into the abdomen. |

13. | Document the procedure, patient’s conditions and state, amount of drainage. | Monitor and evaluate progress |

14. | Observe the patient’s condition and vital signs, half hourly and record while the fluid is draining and after the procedure. | To ensure that the patient’s condition is stable. |

15. | The sterile tray for dressing is left at the bedside. | To save time when required |

Procedure Care

Post-procedure Care

Sites

Positioning

Withdraw fluid slowly and apply clamps on the tubing.

Withdraw small quantities of fluid at a time.

Apply pressure on the abdomen with a many-tailed bandage, tightening it from above downwards as the fluid is drained.

Keep the client warm.

Continuously observe vital signs during the procedure.

Drainage Management:

Raise the drainage receptacle on a stool. The greater the vertical distance between the tapping needle and the end of the tubing in the drainage receptacle, the faster the fluid is drained, increasing the risk of shock.

Use a smaller gauge tapping needle/trocar to reduce puncture wound size and fluid leakage risk post-procedure.

Control the fluid flow using clamps on the tubing.

The nurse should remain with the client throughout the procedure to observe general condition and report any changes in color, pulse, respiration, or blood pressure to the doctor immediately, as these may indicate vascular shock and collapse.

Post-procedure Management:

Repeated aspirations of ascitic fluid can result in hypoproteinemia; administer plasma protein if needed.

Seal the wound immediately after the procedure to prevent infection and fluid leakage.

Send collected specimens to the laboratory promptly.

Aftercare of the Client

Any changes in color, pulse, respiration, and blood pressure should be reported immediately.

Vital signs should be checked half-hourly for two hours, then hourly for four hours, followed by four-hourly checks for 24 hours.

Specimen Handling: Send collected specimens to the laboratory with labels and a requisition form.

Dressing Examination: Frequently examine the dressing at the puncture site for any leakage. Reinforce the dressing if leakage is present.

Protein Levels: Estimate serum proteins to detect hypoproteinemia. Administer plasma proteins if hypoproteinemia is present.

Documentation: Record the procedure in the nurse’s record with date and time. Note the amount and character of the fluid drained, its color, and the effects of the treatment on the client.

Cleaning Equipment: Clean all used articles by washing with cold water, then warm soapy water, and rinse in clean water. Dry and send for autoclaving.

Prepare For Abdominis Paracentesis (Abdominal Tapping) Read More »

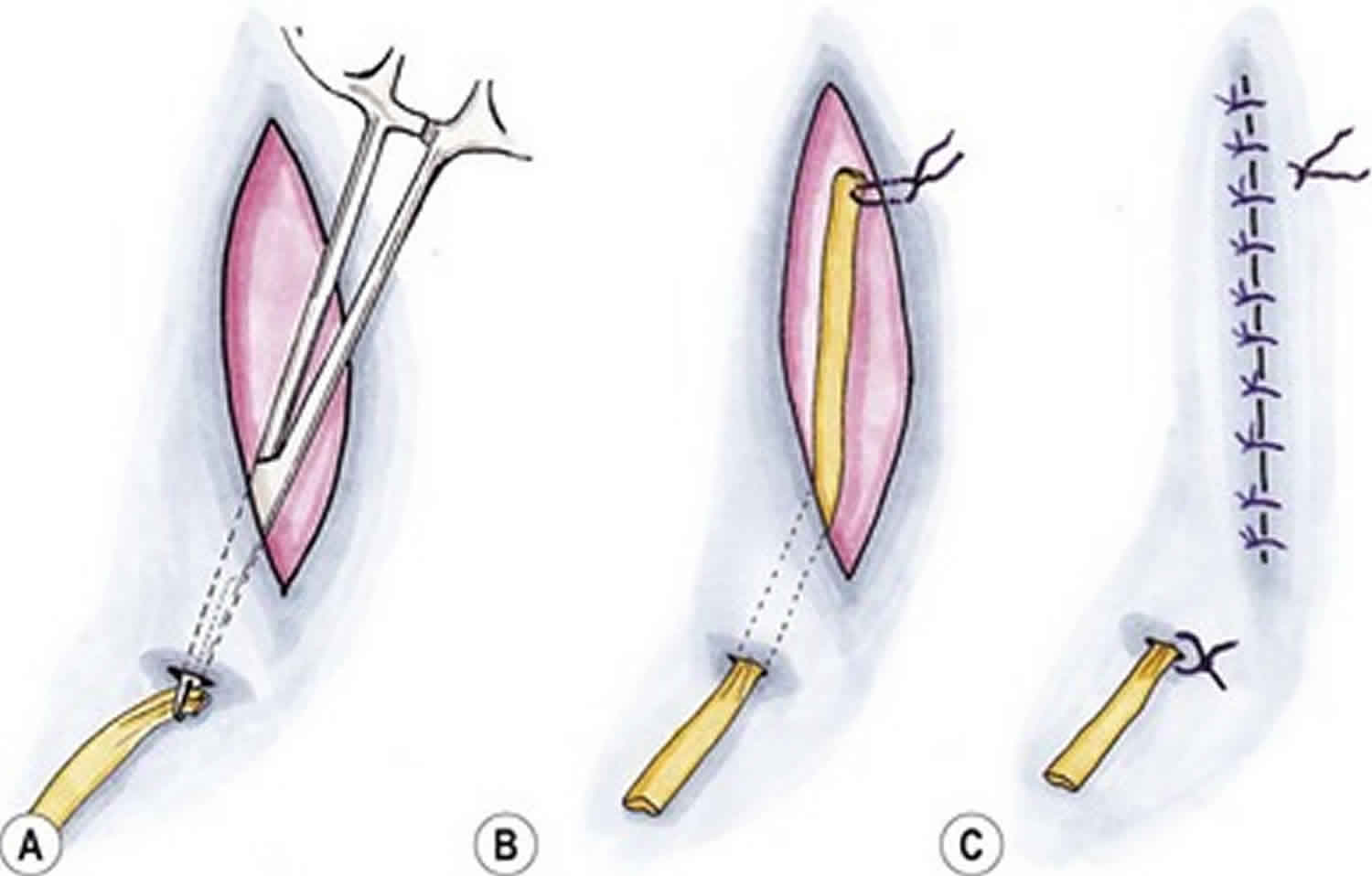

Shortening and removal of drains refers to the process of adjusting or cutting to an appropriate length and then removing medical devices that are used to drain fluids or provide access to specific areas within the body

A drain: A surgical implant that allows removal of fluid and/or gas from a wound or body cavity.

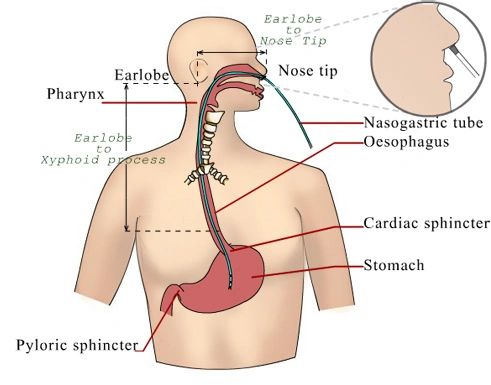

Nasogastric Tube (NG Tube):

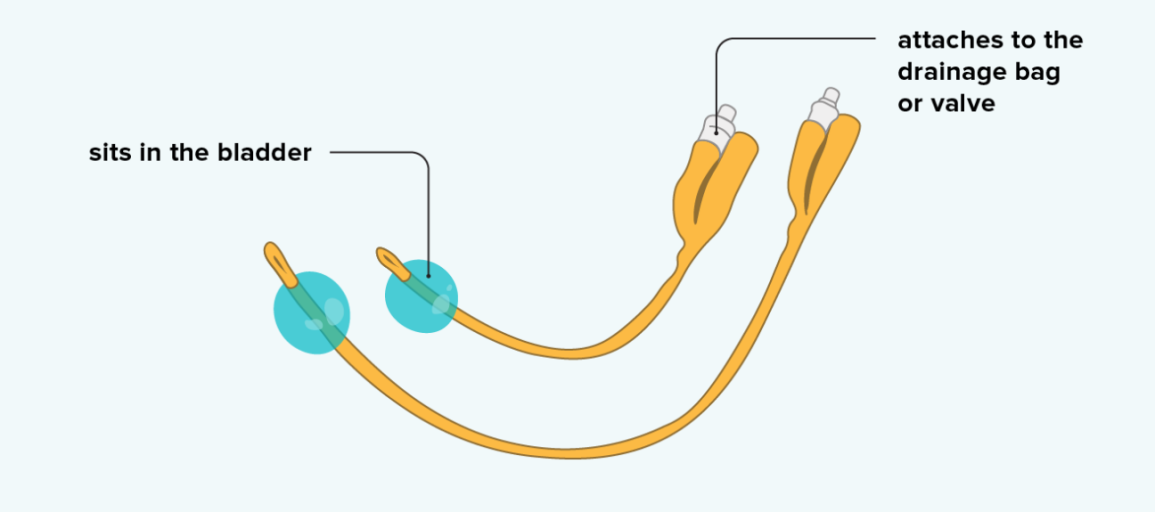

Foley Catheter (Indwelling Urinary Catheter):

Ventriculoperitoneal Shunt (VP Shunt):

Central Venous Catheter (CVC):

Thoracostomy Tube (Chest Tube):

Drains are categorized based on various factors, including their functionality and design. Here, we discuss the classifications of drains:

Open Drains:

Closed Drains:

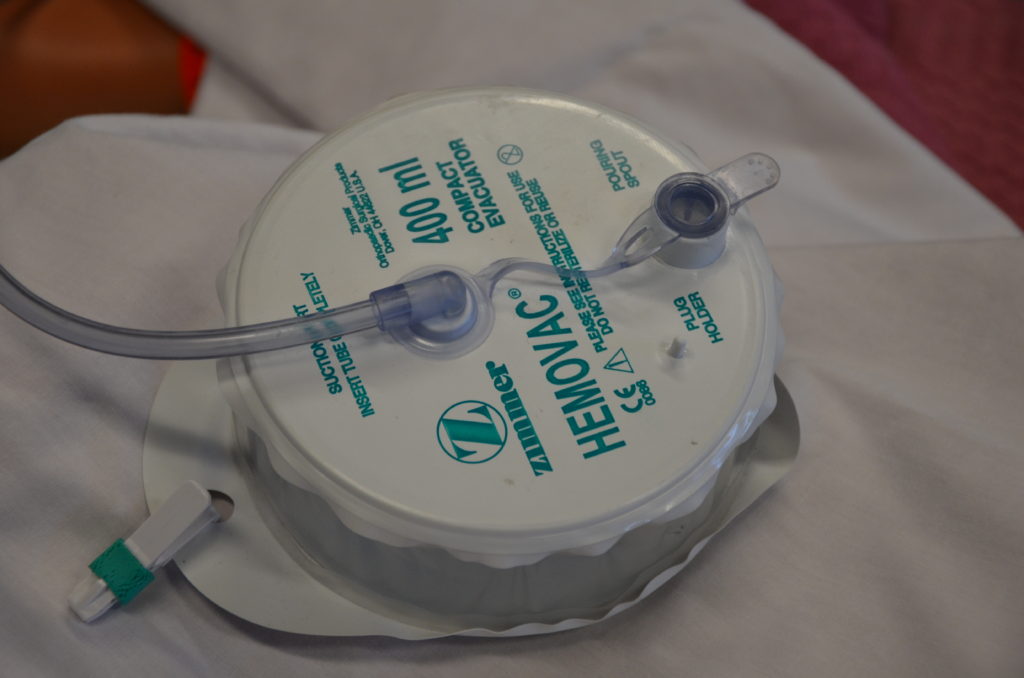

Active Drains:

Advantages of Active Drains:

Disadvantages of Active Drains:

Passive Drains:

Advantages of Passive Drains:

Disadvantages of Passive Drains:

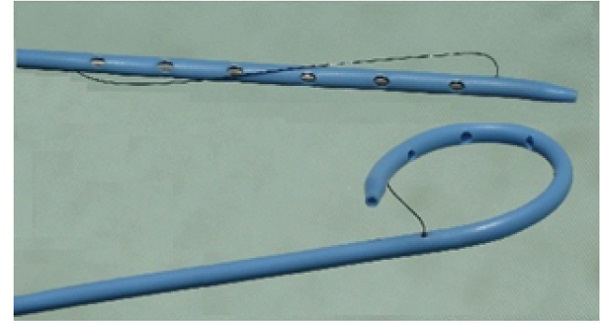

Pigtail Drain:

Disadvantages:

Hemovac Drain:

Disadvantages:

Penrose Drain (Open Drain):

Disadvantages:

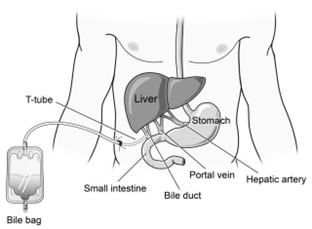

T-Tube:

Disadvantages:

Chest Tube (Closed Drain):

Disadvantages:

Nasogastric Tube (NG Tube):

Disadvantages:

Urinary Catheters:

Disadvantages:

Requirements

Top Shelf | Bottom Shelf |

Stitch removing pack containing | Bottle of antiseptic solution |

– Stitch Scissors | |

– Non-toothed dissecting forceps | |

– 2 dressing forceps | |

– Cotton wool swabs | |

– Gauze | |

– Sterile gloves | |

– Sterile safety pin | |

– Sterile dressing towel | |

– Receiver |

Procedure

Steps | Action | Rationale |

1. | First clean the wound as for surgical dressing. | To reduce the risk of spreading infections. |

2. | Cut and remove the stitch between the drain and the skin. | To loosen the drain. |

3. | Take out the drain and place it in a receiver. | To prevent cross-infection. |

4. | Gently compress the area, clean the wound, and apply a dressing. | Compression is done to drain the wound. |

5. | Finish up as for simple dressing. | To protect against inversion of microorganisms. |

6. | Document procedure. | For follow-up care. |

Steps | Action | Rationale |

1. | Clean wound as for surgical dressing. | To prevent cross-infection. |

2. | Pull the drainage tube with the dissecting forceps. If it is the first dressing post-operatively, there will be a need to cut the stitch between the drain and the skin before adjusting to the prescribed length. | To loosen the drainage. |

3. | Use sterile forceps or gloves to insert the safety pin across the drain and to close the pin. | To secure the drain in position and to prevent infection. |

4. | Dress the wound and finish as for a simple dressing. | To prevent inversion of microorganisms. |

5. | Document the procedure. | For easy continuity of care. |

Hospital Standards Procedures.

Steps | Action | Rationale |

1. | Perform hand hygiene.

| Hand hygiene reduces the risk of infection. |

2. | Collect necessary equipment. | Having the required supplies readily available, such as a drainage measurement container, non-sterile gloves, waterproof pad, and alcohol swab, ensures a smooth and efficient procedure. |

3. | Apply non-sterile gloves and goggles or a face shield where necessary.

| Personal protective equipment (PPE) reduces the transmission of microorganisms and protects against accidental exposure to body fluids. |

4. | Maintaining principles of asepsis, remove the plug from the pouring spout as indicated on the drain.

| Aseptic technique is crucial to prevent contamination. Opening the plug away from your face reduces the risk of accidental splashing of body fluid. |

5. | Gently tilt the opening of the reservoir toward the measuring container and pour out the contents. Note the character of drainage: color, consistency, odor, and amount. | Pouring away from yourself prevents exposure to body fluids. Monitoring and documenting the characteristics of drainage are essential for patient care and record-keeping. |

6. | Swab the surface of the pouring spout and plug with an alcohol swab. Place the drainage container on the bed or a hard surface, tilt it away from your face, and compress the drain to flatten it with one hand. | Swabbing with alcohol maintains cleanliness. Flattening the drain before closing helps expel air, ensuring efficient functioning of the drainage system. |

7. | Place the plug back into the pour spout of the drainage system, maintaining asepsis. | Reinserting the plug while maintaining aseptic principles reestablishes the vacuum suction in the drainage system. |

8. | Secure the device onto the patient’s gown using a safety pin; ensure the drain is functioning; make sure that enough slack is present on the tubing. | Securing the drain minimizes the risk of inadvertent removal. Providing adequate slack accommodates patient movement and prevents tension at the drain insertion site. |

9. | Discard drainage according to agency policy. | Proper disposal procedures protect healthcare workers against exposure to blood and body fluids. |

10. | Remove gloves and perform hand hygiene. | Hand hygiene should be performed after removing gloves, as gloves are not puncture-proof or leak-proof. Hands may become contaminated during glove removal. |

11. | Document the procedure and findings accordingly. Report any unusual findings or concerns to the appropriate healthcare professional. | Documentation ensures accurate recording of drainage and any changes. If multiple drains are present, numbering and noting their locations in the chart is essential. Any significant changes or concerns must be reported to the healthcare provider per agency policy. |

Steps | Action | Rationale |

1. | Confirm that the prescriber’s order correlates with the amount of drainage in the past 24 hours. | Ensuring the prescriber’s order aligns with recent drainage amounts is crucial for safe removal. It helps avoid early removal if the drainage is not yet at an acceptable level. |

2. | Explain the procedure to the patient; offer analgesia and a bathroom visit as required. | Patient education and offering analgesia reduce anxiety about the procedure. Preparing the patient for the sensation they might experience during removal promotes cooperation. Analgesia ensures comfort during the procedure. |

3. | Assemble supplies at the patient’s bedside: dressing tray, sterile suture scissors or sterile blade, cleansing solution, tape, garbage bag, outer dressing. | Organizing supplies in advance ensures efficiency and readiness for the procedure, enhancing patient safety and comfort. |

4. | Apply a waterproof drape or mackintosh for setting the drain onto once it has been removed. | This provides a designated place for the removed drain, preventing contamination and maintaining cleanliness. |

5. | Perform hand hygiene. | Hand hygiene before the procedure reduces the risk of introducing microorganisms from other sources to the patient. |

6. | Apply non-sterile gloves and PPE accordingly. | Wearing non-sterile gloves and appropriate PPE as assessed at the point of care reduces the risk of transmission of microorganisms and provides added protection against contamination. |

7. | Release suction on the reservoir and empty; measure and record volumes greater than 10 ml. Remove the dressing. | Releasing suction ensures safe removal. Measuring and documenting the drainage volume is crucial for patient care and record-keeping. |

8. | Clean and dry the incision and drain site following principles of asepsis. | Preparing the wound and surrounding area through aseptic cleaning minimizes the risk of infection. |

9. | Carefully cut and remove the securing suture following principles of asepsis. | Removing the suture safely is essential to avoid complications and ensure smooth removal of the drain. |

10. | While holding two to three 4 × 4 sterile gauze in the non-dominant hand, stabilize the skin. | Sterile gauze helps absorb any additional drainage during the removal process, reducing the risk of introducing microorganisms. Stabilizing the skin minimizes discomfort to the patient during the procedure. |

11. | Ask the patient to take a deep breath and exhale slowly; remove the drain as the patient exhales. Firmly grasp the drainage tube close to the skin with the dominant hand, and with a swift and steady motion, withdraw the drain. | Patient cooperation, distraction, and timed removal reduce discomfort. The gentle resistance felt during removal is expected, but if resistance is strong, taking a pause and encouraging relaxation is essential. |

12. | Place the drain and tubing onto a waterproof pad or into a garbage bag. Remove gloves. | Proper disposal prevents contamination of the environment and maintains hygiene. |

13. | At this point, some nurses may clean and dry the wound. | The decision to clean the wound can vary based on the specific situation and healthcare provider’s preferences. |

14. | Dress the wound with a sterile dressing. | Dressing the wound post-removal is essential as drain sites may continue to drain for a few days. |

15. | Discard the drain and garbage. | Proper disposal follows agency policy and decreases the risk of exposure to blood and body fluids for others. |

16. | Perform hand hygiene. | Hand hygiene after the procedure minimizes the risk of contamination. |

17. | Assess the dressing 30 minutes after drain removal. Likewise, ask the patient to call if they notice any increased drainage from the site. | Monitoring for changes in drainage after removal is essential for patient safety and early detection of complications. |

18. | Document the procedure (including drain removal, drain output and characteristics, how the patient tolerated the procedure, dressings applied) accordingly. Report any unusual findings or concerns to the appropriate healthcare professional. | Accurate and timely documentation and reporting are crucial for patient care and safety, ensuring that any concerns are addressed promptly. |

Important Points in the Care of Closed Drainage

Step | Action | Rationale |

1 | Maintain the end of the tube from the wound below the water in the drainage bottle. | This prevents air from passing back up the tube into the wound. |

2 | Seal the tubing first with either clips or artery forceps before emptying the bottle. | To prevent air entry into the lungs. |

3 | Measure the amount of water or antiseptic in the drainage bottle and subtract this amount from the total when measuring the drainage. | To get the correct amount of fluid drained from the wound. |

4 | Observe for any abnormal deposits, colour, and odour. | To aid diagnosis and follow up/progress. |

5 | Keep a clip or artery forceps at the bedside incase of an accident to the tubing. | To be able to clip the tube immediately to prevent air going to the lungs in case of accident to the tubing. |

6 | Maintain sterility of the bottle and should never be lifted up to the bed level or above. | To maintain asepsis and also to prevent back flow of fluid from the drainage chamber to the pleural cavity. |

PERFORM SHORTENING AND REMOVAL OF DRAINS Read More »

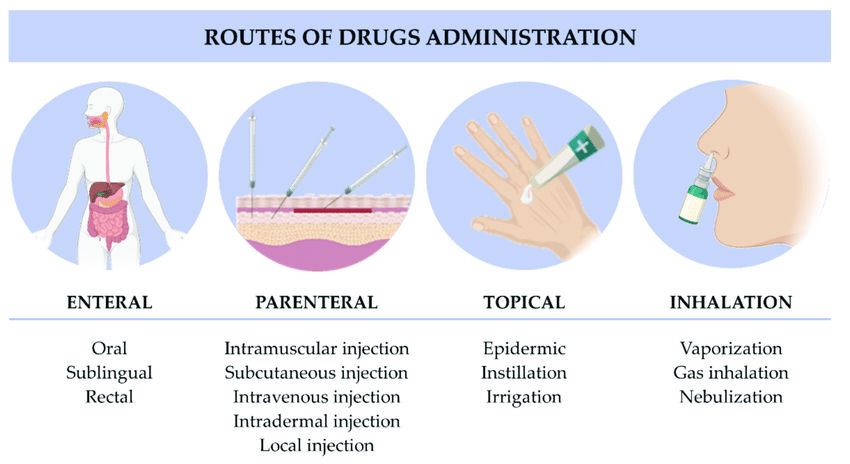

A medicine is any chemical substance in a regulated dose intended for use in the medical diagnosis, cure, treatment, or prevention of disease or any substance that is prescribed and administered to patients to produce therapeutic effects in the body.

The rights that should be observed:

SYSTEMIC ROUTE

ENTERAL ROUTE

LOCAL ROUTE

INHALATION

Inhalation is the breathing of air vapor or volatile medicine into the lungs.

Types

Liquids:

Solids and Semisolids:

Time for Administering Medication

Abbreviations Used in Prescriptions

|

|

Requirements

Trolley

Top Shelf:

| Bottom Shelf:

Bedside:

|

Procedure for Oral Administration

Steps | Action | Rationale |

1. | Follow general rules of nursing procedures. | Ensures accuracy and prevents errors |

2. | Observe the rules of medicine administration. | Ensures accuracy and prevents errors |

3. | Arrange medication trolley in nurse’s station. | To save time and reduce error in medication administration |

4. | Prepare medicine of one patient at a time, keeping medicine lists/charts together. | Ensures accuracy and prevents errors |

5. | Verify the order for medication from the patient’s chart comparing with the medicine list and the label on the bottle. | Ensures accuracy |

6. | Check the label on the medicine container three times (i.e. when taking it from the shelf, before pouring it into the medicine cup and before returning it to the shelf). | Ensures accuracy |

7. | For tablets/capsules, pour required number from bottle into bottle cap and transfer to medication cup, for packaged tablet/capsule pour directly over the cup retain the strip. | Reduces errors in medication administration |

8. | For liquid, hold medication cup to eye level and pour the prescribed amount. | Ensures accuracy |

9. | For volume of less than 5ml, use a 5ml syringe without a needle to measure the amount prescribed. | Ensures accuracy |

10. | Keep the label on the bottle uppermost against the palm of hand when pouring. | To avoid spilling liquid in place. |

11. | Wipe the rim of the bottle before replacing the cork. | Prevents cap from sticking. |

12. | Use only the dropper-supplied with liquids measured in drops. | Ensures accuracy |

13. | Read the label again before replacing the container on the trolley. | Third check reduces errors. |

14. | Place the measuring cup on the tray together with the drinking cup with water and then take it to the patient at the correct time. | Ensures timely administration |

15. | Call the patient’s name, check the room or bed number against the medicine list before giving the medicine. | Confirms the patient’s identity |

16. | Assess the patient’s condition including the level of consciousness and vital signs. For instance patients having digitalis the pulse rate should be checked before administering the medicine. | To rule out likely contraindications or side effects. |

17. | Explain to the patient the medications to be given to the patient and clarify any questions or doubts. | Promotes the patient’s rights and compliance. |

18. | Assist patient in sitting or side lying position. | Prevents aspiration |

19. | Administer medicine properly, only one medicine at a time and offer a glass of water or milk. | Aids swallowing. |

20. | If a patient has difficulty swallowing, grind the tablets in a mortar with pestle, crush it to fine powder and mix it with a small amount of water. | To ease swallowing. |

21. | Prepare powdered medication at the bedside and give it to the patient. | Increases compliance. |

22. | Give effervescent tablets immediately after dissolving. | It helps to improve the taste of medicine. |

23. | If the patient is unable to hold medication in hand; assist to place the cup to the lip and slowly transfer medicine into the mouth using a spoon. | To support the patient. |

24. | If medicines fall on the floor, discard and replace them. | To avoid contaminated medicine |

25. | Stay with the patient until the medicine has been swallowed; if the patient is confused or disoriented his/her mouth should be checked to confirm that the patient has swallowed the medicine. If the medicine is vomited within 5 minutes report to the In-charge or Doctor. Medicines must never be left on the bedside table. | Ensures that patient receives prescribed medication at the correct time |

26. | Assist the patient to a comfortable position. | Maintains patient’s comfort |

27. | Dispose of soiled supplies, clean work area and wash hands. | Reduces transmission of infection |

28. | Document the administration of the medication with date, time and signature immediately after administration. | To avoid errors and promote proper accountability. |

29 | Reassess the patient’s response to the medicine within one hour after giving it and any ill effects reported. | To detect therapeutic/ side effects or adverse effects. |

30 | The medicine cups are washed and returned to their proper place. | Promote hygiene. |

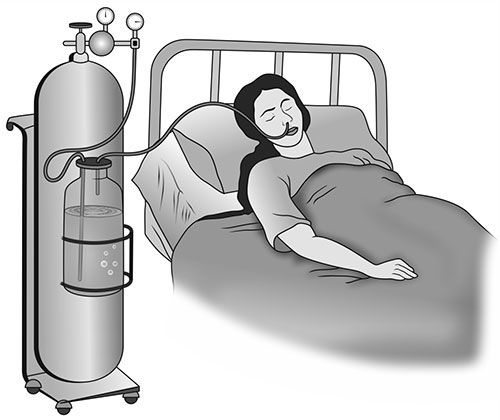

Inhalation is the breathing of air vapor or volatile medicine into the lungs.

Types

It is given when the respiratory tract is diminished as in chest injuries, cardiac failure and pneumonia.

REQUIREMENTS FOR OXYGEN ADMINISTRATION

Clean tray

Bedside

PROCEDURE

Steps | Action | Rationale |

1 | Refer to the general rules | Keeps standard |

2 | Turn and test the oxygen cylinder before bringing everything to the bedside | Conserves time and energy |

3 | Determine need for oxygen therapy in patient and check physician’s order for rate, device used, concentration | Reduces risk of error in administration |

4 | Position patient in sitting up or one side | Promotes comfort |

5 | For nasal cannula use; connect nasal cannulae to oxygen set up with humidification, check if oxygen is flowing out of prongs | Humidification prevents dehydration of mucous membranes |

6 | Place prongs in the patient’s nostrils 2 inches, place tubing over and behind each ear with adjuster comfortably under the chin or place tubing around the patient’s head with the adjuster at the back or base of the head and place gauze pads at ear beneath the tubing as necessary | Facilitates oxygen administration and patient comfort. Pads reduce irritation and pressure |

7 | Encourage patient to breathe through the nose, with the mouth closed | Nose breathing provides for optimal delivery of oxygen to the patient |

8 | For B.L.B mask use; attach face mask to oxygen source start the flow of oxygen at the specified rate, for a mask with a reservoir allow oxygen to fill the bag before proceeding to the next step | The bag is the oxygen supplier to the patient |

9 | Position the face mask over the patient’s nose and mouth, adjust the elastic strap around patient’s head, adjust the flow rate | A loose or poorly fitting mask will result in oxygen loss |

10 | Apply padding behind ears as well as scalp where elastic band passes | Padding prevents skin irritation |

11 | Reassess patient’s respiratory status, including respiratory rate, effort, and lung sounds | Assesses effectiveness of oxygen therapy |

12 | Document relevant information in the patient’s record | Ensures accurate medical records |

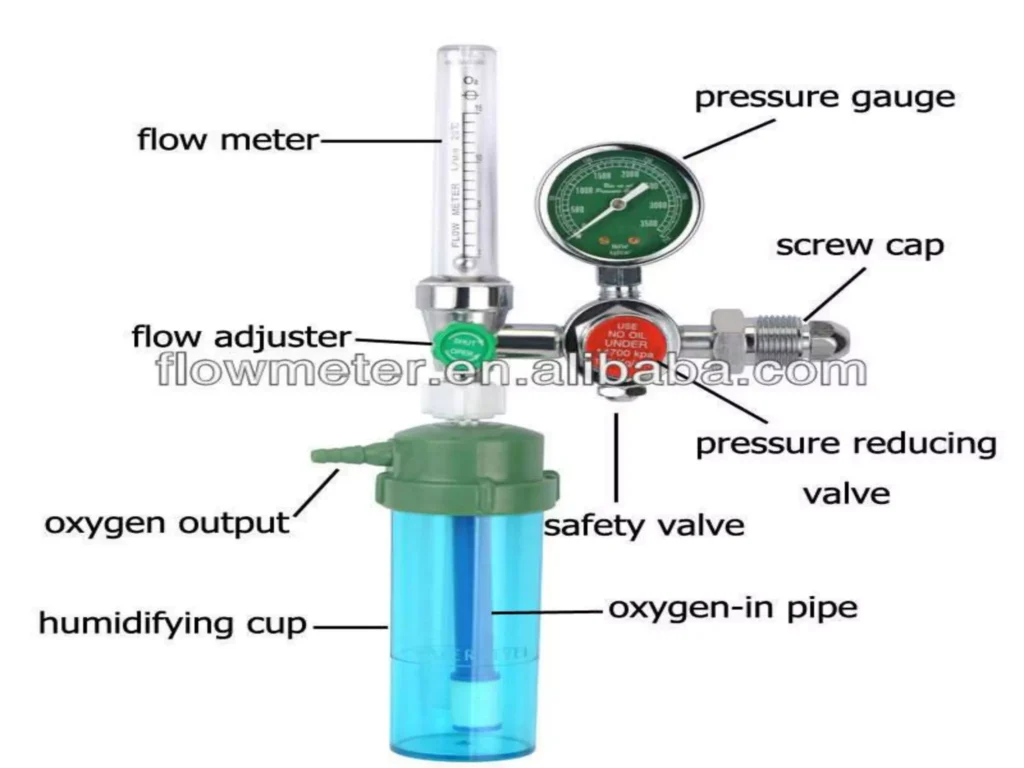

Parts of an Oxygen Flowmeter

Requirements

Trolley

Top shelf | Bottom shelf |

|

|

Bedside | |

|

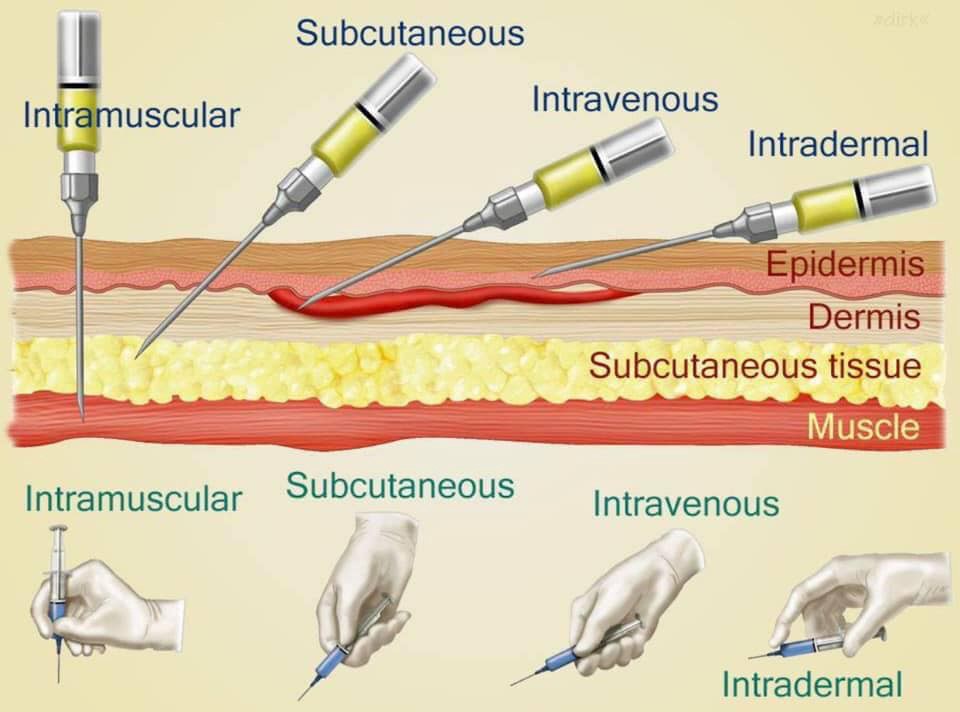

Procedure

Steps | Action | Rationale |

1. | Refer to general and medicine administration rules for injections. | |

2. | A tuberculin syringe or 1 ml syringe is used and needles. | |

3. | Identify the patient, put in a comfortable position. | |

4. | Clean the skin with an antiseptic swab and allow the site to dry. | Exposes the selected site. |

5. | If it is a BCG vaccination, clean the site with water. | |

6. | Stretch the patient’s skin, draw it tight and introduce the needle at an angle parallel to the skin. | |

7. | Gently and slowly inject the medicine while observing for a small wheal to appear. | |

8. | Carefully withdraw the needle. | |

9. | Do not massage the site after removing the needle. | This may alter the test results. |

10. | Circle the area with a pen and record time, and request the patient not to wash the area until it is assessed for the intended outcome. | If it was for diagnostic purposes e.g., Mantoux test. |

11. | Inspect for signs of reaction when the stated duration of time has reached. | |

12. | Report and record results. | |

13. | Clean away the used equipment. |

Steps | Action | Rationale |

14. | Help patient assume position depending on site selected. | Ensures free access to site. |

15. | Choose a suitable needle gauge; take a 1 ml or 2 ml syringe depending on the dosage. | |

16. | Draw the medicine into the syringe. | |

17. | Expel the air by holding the syringe with the needle pointing up. | |

18. | Place the syringe in the injection dish. | |

19. | Explain the procedure to the patient, asking him/her not to move while the injection is being given. | Encourages cooperation and allays anxiety. |

20. | Select the site and clean it with an antiseptic swab and let the area dry first. | |

21. | Grasp and pinch or squeeze the patient’s skin gently between the finger and thumb of your left hand and insert the needle at an angle of 45°. | Provides for easy and less painful entry into subcutaneous tissue. |

22. | Pull back the (piston) plunger and inject the medicine slowly. | Determines if the needle is in a blood vessel. |

23. | When the medicine has been injected completely, place a swab over the needle and withdraw the needle quickly and smoothly. | Reduces discomfort. |

24. | If there is any bleeding at the site, apply firm gentle pressure with a swab until it stops. | |

25. | Make the patient comfortable and record the medicine given on the patient’s treatment sheet. | |

26. | Discard syringe, gloves, and swabs appropriately and clear away the equipment. | Promotes infection control measures. |

Steps | Action | Rationale |

27. | Observe the general nursing rules. | |

28. | Read the prescription carefully and check the medicine with the other nurse, including the amount to be given. | |

29. | Assemble syringe and needle, put on gloves. | |

30. | Break open the top of the ampoule (by using a gauze swab or a file) or remove the top of the rubber cap. | |

31. | Reconstitute powdered medicines according to the instructions on the bottle. | |

32. | Put on gloves and draw up the prescribed dose of the medicine. | |

33. | Expel the air and remember that with antibiotics and multi-dose vials, the air is expelled into the container. | |

34. | Position the patient depending on the site chosen. | Proper positioning ensures muscle relaxation of the patient. |

35. | Select, locate, clean the site and allow it to dry. | |

36. | Inject the medication; grasp and pinch the area surrounding the injection site or spread skin at site as appropriate. | Aids needle penetration in patients with thick muscles. |

37. | Hold the syringe between thumb and forefinger and pierce skin at a 90° angle and insert the needle. | |

38. | Aspirate by holding the barrel steady with a non-dominant hand. | Helps to check if a needle is in a blood vessel. |

39. | If the blood does not appear in the syringe, inject the medication slowly and steadily. | Helps to disperse medication into muscle tissue, thus decreasing a patient’s discomfort. |

40 | Withdraw the needle slowly and steadily while supporting at the hub of the syringe and needle. With non-dominant hand support the skin surface using cotton swab for applying counter traction at the site | Helps to reduce discomfort and prevent pulling of tissues when needle is withdrawn |

41 | Apply gentle pressure at the site with a dry cotton swab but do not massage. | Massaging irritates tissues at the injection site. |

42 | Discard the un capped needle and syringe appropriately. | Promotes infection prevention and control. |

43 | Clear away, remove gloves and wash hands. | |

44 | Record procedure including the name of medication, dose, site and response of the patient. | Reduces chances of medication errors |

Steps | Action | Rationale |

45. | Prepare the injection tray and take it to the patient’s bedside. | Ensures all necessary items are available for the procedure. |

46. | Identify the patient and explain the procedure to the patient. | Alleys anxiety. |

47. | Screen the bed and put on gloves. | Provides privacy. |

48. | Place a small pillow and a protective sheet under the patient’s arm. | Promotes comfort and protects the beddings. |

49. | Expose the patient’s forearm and anterior surface of the elbow. | Ensures easy access to the injection site. |

50. | Inspect the selected vein, if it is visible and clear; apply a tourniquet or a sphygmomanometer cuff around the patient’s upper arm and inflate sufficiently about 8 to 10 cm above the site. | Helps to distend and enlarge the vein. |

51. | Request the patient to close and open the fist for a minute. | Promotes venous filling and visibility. |

52. | Clean the area with an antiseptic and dry with a sterile swab. | Reduces microorganisms. |

53. | Expel air from the syringe. | Ensures accurate dosing and prevents air embolism. |

54. | Hold the patient’s arm and with your left thumb exert pressure about 3 cm below the chosen site and make the skin tight. | Stabilizes the vein and reduces movement. |

55. | Insert the needle at an angle of 15-45 degrees with its bevel up then quickly and steadily insert into the vein. Pull back the piston slightly if blood is aspirated. | Ensures that the needle is in the vein. |

56. | Remove the tourniquet or deflate the cuff and inject the medicine slowly. | Prevents excessive pressure in the vein and ensures proper delivery of medication. |

57. | When the medicine is injected, put a swab over the site and withdraw the needle. | Minimizes bleeding and ensures cleanliness. |

58. | Apply pressure at the site with a swab for some seconds to make sure there is no bleeding. If oozing continues, apply a swab and a piece of strapping. | Prevents bleeding. |

59. | Record the medicine in the patient’s chart and clear away. | Ensures accurate medical records and maintains order. |

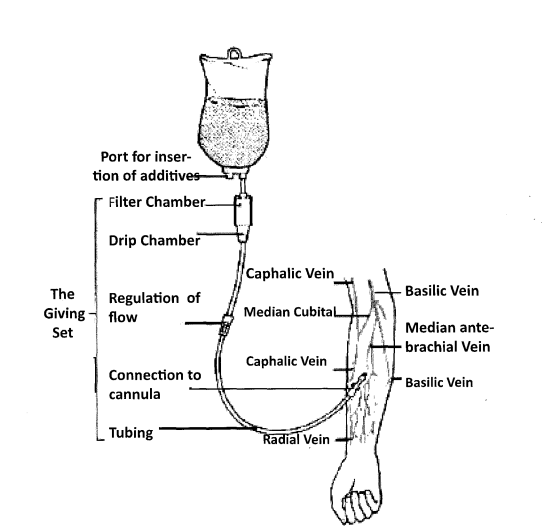

SOME OF THE RECOMMENDED VEINS FOR INTRAVENOUS INFUSION

BACK OF THE HAND | FOREARM | LOWER EXTREMITY |

Dorsal metacarpal veins | Basilic vein | Femoral and saphenous vein in the thigh Dorsal venous plexus, medial and lateral marginal veins in the foot |

Common Sites for Intramuscular Injections

1. Abscess Formation: This occurs when unsterile needles and syringes are used, or when oily substances are not injected deep enough. The injection site becomes inflamed and filled with pus.

2. Nerve Injury: Incorrectly positioning the needle can damage nearby nerves, causing pain, numbness, weakness, or paralysis.

3. Tissue Damage/Necrosis: Injecting too much medication, using irritating substances, or repeated injections in the same site can lead to tissue damage and cell death.

4. Hematoma: A hematoma forms when blood leaks into the surrounding tissue after the injection, causing a bruise or swelling.

5. Pain and Discomfort: Intramuscular injections can be painful, especially if the medication is irritating or the injection technique is not correct.

6. Allergic Reactions: Some individuals may have an allergic reaction to the medication or the ingredients in the solution.

7. Injection into a Blood Vessel: The needle may unintentionally enter a blood vessel, leading to potential complications like drug overdose or embolism.

8. Delayed-Onset Muscle Soreness: Some medications can cause muscle soreness or stiffness that may not appear until several hours or days after the injection.

9. Infection: Improper sterile technique can lead to infection at the injection site.

10. Air Embolism: Although rare, air can be injected into the bloodstream, leading to complications like respiratory distress or cardiac arrest.

Intravenous infusion equipment and the superficial veins of the forearm that may be cannulated

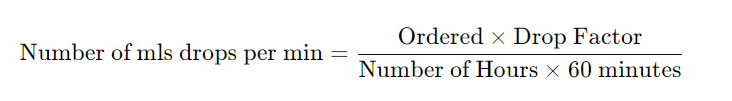

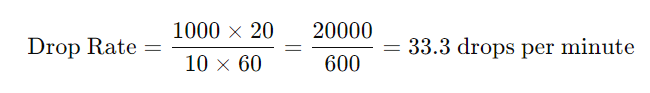

To calculate the drop rate, use the following formula:

Example:

The doctor has prescribed 1000 mls of 5% dextrose infusion to run in 10 hours. How many drops per minute will you regulate if the infusion set has a drop factor of 20?

Administer drugs appropriately Read More »

The Nursing process is an organized, systematic, dynamic method of giving individualized nursing care that focuses on identifying and treating unique responses of individuals or groups, to actual or potential alterations in health. (Nursing procedure Manual, 2015)

OR:

The nursing process is defined as a systematic, rational method of planning that guides all nursing actions in delivering holistic and patient–focused care.

Explain the components of the nursing process

1. Assessment

2. Diagnosis

3. Planning

4. Implementation

5. Evaluation

The first phase of the nursing process is assessment.

It involves collecting, organizing, validating, and documenting the clients’ health status. Assessment involves data collection which is the process of gathering information regarding a client’s health status. The main methods used to collect data are health interviews and physical examination.

Types of data collected

A nursing diagnosis is a clinical judgment concerning a human response to health conditions/life processes, or a vulnerability to that response, by an

individual, family, group, or community.

NB: Medical diagnosis is different from a nursing diagnosis because nursing diagnosis refers to human response to health conditions whereas the medical diagnosis focuses on health conditions.

1. Actual nursing diagnosis

Scenario A: A patient complaining of fevers, on thermometer reading it indicates 38°C.

From NANDA 2024 – 2026 fevers have hyperthermia i.e.

Hyperthermia related to increased leukocyte activity evidenced by the thermometer reading of 38°C.

Scenario B: A patient complained of headache of the forehead since the last 2 days after a minor head injury following a fight. On examination the pain was at 3 on a 0 – 5 pain scale.

From NANDA 2024 – 2026 headache is described as Acute pain since it has been present less than 3 months.

-Acute pain related to trauma to the head evidenced by the patient’s verbalization of feeling headache of 3 on a 0 – 5 pain scale.

2. Potential Nursing diagnosis:

Scenario: A patient reported vomiting for 1 day after ingesting chips and chicken. On examination the patient had no signs of dehydration.

From NANDA 2024 – 2026 vomiting does not have an actual nursing diagnosis it only has a potential nursing diagnosis which is risk for inadequate fluid volume.

–Risk for inadequate fluid volume related to vomiting.

The planning stage is where goals and outcomes are formulated that directly impact patient care.

Planning phase is divided into

1. Goals

2. Expected outcomes

Goals should be:

Goals are divided into 3 categories i.e.

1. Short term goals: these are goals having time limit ranging from minutes to 5 days.

2. Intermediate goals: these are goals having time limit ranging from 5 days to 30 days.

3. Long term goals: these are goals having time limit ranging from 30 days to years.

The implementation phase of the nursing process is when the nurse puts the treatment plan into effect.

It involves action or doing and the actual carrying out of nursing interventions outlined in the plan of care.

The implementation phase is divided into two parts

Evaluating is the fifth step of the nursing process. This final phase of the nursing process is vital to a positive patient outcome. Once all nursing intervention actions have taken place, the team now learns what works and what doesn’t by evaluating what was done beforehand. This is the past tense of the outcome if they have been

achieved.

SO IN BRIEF

Assessment:

Diagnosis:

Planning (Goals/Expected Outcomes):

Goals:

Expected Outcomes:

The patient will verbalize that he no longer feels feverish. Thermometer reading will be between 36.0°C to 37.4°C.

Implementation:

Rationale:

Evaluation:

Sample Nursing Care Plan for a patient with Malaria

Assessment | Diagnosis | Planning (Goals or Expected Outcomes) | Implementation/ Interventions | Rationale | Evaluation |

Fever | Hyperthermia related to leucocyte activity as evidenced by an elevated temperature of 39° C. | Reduce fever to 37° C within 30 minutes. | – Administer antipyretic medication as prescribed. – Encourage adequate fluid intake. – Apply cooling measures (e.g., tepid sponging). | – Antipyretic medication helps lower the fever. Adequate fluid intake prevents dehydration. Cooling measures aid in reducing body temperature. | Fever reduced to 37° C |

Headache | Acute Pain related to malarial infection evidenced by patient verbalizing headache. | Alleviate headache within 40 minutes. | – Administer analgesic medication as prescribed. – Provide a quiet and dimly lit environment. – Encourage relaxation techniques (e.g., deep breathing). | – Analgesic medication helps relieve pain. – A quiet environment reduces stimuli that may exacerbate the headache. – Relaxation techniques promote comfort. | Headache Alleviated with In 40 minutes With a pain Scale reading Of 1/10. |

Myalgias | Impaired Physical Mobility related to muscle pain and weakness as evidenced by difficulty in movement. | Improve mobility and reduce muscle pain within 5 days. | – Encourage gentle stretching exercises. Administer analgesic medication as prescribed. – Provide warm compresses to affected areas. | – Gentle stretching improves flexibility and reduces muscle pain – Analgesic medication helps relieve pain. – Warm compresses promote muscle relaxation. | Improved mobility and reduced muscle pain After 5 days. |

Nausea | Nausea related to changes in eating habits as evidenced by patient complaints and increased salivation | Alleviate nausea within 1 hour. | – Administer antiemetic medication as prescribed. – Encourage small, frequent meals. – Provide oral hygiene measures after vomiting episodes. | – Antiemetic medication helps alleviate nausea. – Small, frequent meals are easier to tolerate. – Oral hygiene measures prevent discomfort and promote a sense of well-being. | Patient vebalised That no nausea After 1 hour.. |

Vomiting | Risk for inadequate fluid volume related to unpleasant sensory stimuli | The client will report decreased severity or elimination of nausea and vomiting. | – Administer antiemetic medication as prescribed. – Monitor and record intake and output. – Provide oral rehydration solutions as needed. | – Antiemetic medication helps control vomiting. – Monitoring intake and output prevents dehydration. – Oral rehydration solutions restore fluid balance. | The client reported elimination of nausea and vomiting. |

Diarrhea | Risk for inadequate Nutritional intake related to less food intake as evidenced by watery stool. | Achieve optimal nutritional intake. | – Administer antidiarrheal medication as prescribed. – Encourage a bland and easily digestible diet. – Monitor and record bowel movements. | – Antidiarrheal medication helps control diarrhea. – A bland diet is easier on the digestive system. – Monitoring bowel movements informs about the effectiveness of interventions. | Achieved optimal nutritional intake |

Dehydration | Risk for impaired fluid volume balance related to diarrhea, nausea and vomiting. | Patient will maintain hydration as evidenced by adequate intake and output, vital signs, and skin turgor | Administer fluids intravenously as indicated. Offer high-water content foods like soups Administer antiemetics as indicated. | Fluids for fluid replacement To encourage rehydration and motility of the bowel. To reduce vomiting episoded | Patient maintained hydration. |

Expected outcomes:

Want this in PDF?

Copy the link

Send it to 0726113908 on WhatsApp

Prepare Shs. 5000 (1.3$)

And you will get the full PDF sent to you on WhatsApp.

Javascript not detected. Javascript required for this site to function. Please enable it in your browser settings and refresh this page.